Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study is to determine whether elderly subjects with severe brain atrophy, which is associated with neurodegeneration and difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), are more susceptible to lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI), including pneumonia.

Methods

The severity of brain atrophy was assessed by computed tomography in 51 nursing home residents aged 60–96 years. The incidence of LRTI, defined by body temperature ≥ 38.0°C, presence of two or more respiratory symptoms, and use of antibiotics, was determined over 4 years. The incidence of LRTI was compared according to the severity and type of brain atrophy.

Results

The incidence rate ratio of LRTI was significantly higher (odds ratio 4.60, 95% confidence interval 1.18–17.93, fully adjusted P = 0.028) and the time to the first episode of LRTI was significantly shorter (log-rank test, P = 0.019) in subjects with severe brain atrophy in any lobe. Frontal and parietal lobe atrophy was associated with a significantly increased risk of LRTI, while temporal lobe atrophy, ventricular dilatation, and diffuse white matter lesions did not influence the risk of LRTI.

Conclusion

Elderly subjects with severe brain atrophy are more susceptible to LRTI, possibly as a result of neurodegeneration causing dysphagia and silent aspiration. Assessing the severity of brain atrophy might be useful to identify subjects at increased risk of respiratory infections in a prospective manner.

Keywords: brain atrophy, dysphagia, elderly, pneumonia, respiratory infection, white matter lesions

Introduction

Brain atrophy is frequently observed in elderly people, based on computed tomography (CT) findings.1 Brain atrophy is a marker of neurodegeneration,2,3 which is often associated with difficulty swallowing (dysphagia).4,5 In turn, dysphagia may cause aspiration pneumonia and lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI).6 From this context, we hypothesized that brain atrophy may represent neurodegeneration, which might result in dysphagia and subsequent respiratory infection. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine this hypothesis and determine whether elderly subjects with severe brain atrophy are more susceptible to LRTI.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The subjects consisted of residents in a nursing home in an urban area of Nagoya City, Japan. Medical care was provided by physicians of the clinic located by the residence. Brain CT was performed on some of the residents at admission to check their underlying cerebrovascular disease, or during follow-up when needed (such as evaluation of dementia and minor head injury). All the residents who underwent brain CT from January 2006 to June 2006 and who could be observed for more than one year were selected retrospectively. Subjects with major infarction identified on brain CT, and subjects on tube feeding were excluded from the study. None of the subjects showed hemiparesis, major neurological dysfunction, or apparent signs of dysphagia.

Information on the subjects’ baseline characteristics was collected from medical records. Hypertension and diabetes mellitus were defined as taking antihypertensive or glucose-lowering medications, respectively. Mobility status was evaluated by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (0–2 and 3–4). Dementia status was assessed by orientation (ie, whether the subject was oriented or disoriented in time, place, and person). The use of major tranquilizers was also assessed. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Nagoya University School of Medicine (2012–0003) and the ethics committee of Nagoya Medical Association.

Assessment of brain CT

All subjects underwent non-contrast brain CT with 10 mm continuous slices using a CT-WS-18A scanner (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Brain CT images were rated and interpreted by a specialized radiologist who was blinded to the subjects’ clinical status. Cortical atrophy was classified as absent, mild to moderate, or severe in four different lobes (frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital) according to anatomical subdivision.1,7 Severe brain atrophy was defined as severe atrophy in at least one lobe. Cortical atrophy was also evaluated based on the four cortical sulci ratio (sum of the widths of the four widest sulci at the two highest scanning levels/maximal transversal intracranial width).8 Ventricular dilatation was evaluated using the Evans ratio (maximal frontal horn width/maximal transversal intracranial width) and the third ventricular ratio (maximal width of the third ventricle/maximal transversal intracranial width).8 White matter lesions in the frontal, parieto-occipital, and temporal regions were evaluated using the Wahlund score,9 given that these regions show the greatest sensitivity in elderly people.1 Lesions were graded as 0 = no lesions, 1 = focal lesions, 2 = beginning of lesion confluence, or 3 = diffuse involvement of the entire region. Lacunar infarction was defined as an area of <5 mm with attenuation on CT similar to that of cerebrospinal fluid, and was classified as no, single, or multiple infarctions. Major infarction was defined as an area ≥ 5 mm with attenuation on CT similar to that of cerebrospinal fluid.

Definition of lower respiratory tract infection

Medical records until the end of December 2009 were used retrospectively. Vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation, body temperature), consciousness and symptoms (eg, sputum, cough, dyspnea, chest pain, abdominal pain) were assessed by trained nurses and the data were recorded in a computerized database. Antibiotics were administered orally or intravenously at the physician’s decision. LRTI was defined based on the following criteria: body temperature ≥ 38.0°C at least once; two or more respiratory symptoms which were new or of increasing severity (sputum, cough, shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, or worsening functional status); and use of oral or intravenous antibiotics.10,11 Infections were defined as new if antibiotics had not been administered for ≥14 days before the event.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared between patients with and without severe brain atrophy using χ2 or Wilcoxon tests. The incidence of LRTI was compared according to the presence of severe brain atrophy, type of brain atrophy (cortical atrophy of each lobe, the four cortical sulci ratio, Evans ratio, and the third ventricular ratio), and the presence of diffuse white matter lesions. Incidence rate ratios were calculated by Poisson regression analysis, taking into account overdispersion using the negative binomial regression model, with adjustment for age and gender, ie, partially adjusted incidence rate ratios, and for age, gender, hypertension, mobility status (assessed by ECOG performance status 0–2 and 3–4), dementia status, major tranquilizer use, and lacunar infarctions (scored as 0, 1, and 2 for none, single, and multiple lacunar infarctions, respectively), ie, fully adjusted incidence rate ratios. The analyses were not adjusted for diabetes because the number of subjects with diabetes was small. Incidence rate ratios were compared between the upper and middle tertiles and the lower tertile of the four cortical sulci ratio, Evans ratio, and the third ventricular ratio. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the first episode of LRTI were plotted according to the severity of brain atrophy, and data were compared by the log-rank test. STATA version 9 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for all analyses. Values of P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The baseline characteristics and brain CT findings of the patients are shown in Table 1. About half of the subjects (24 in 51 subjects) showed severe brain atrophy in any lobe. Although there were some differences between subjects with no/mid brain atrophy and subjects with severe brain atrophy in terms of the proportions of subjects with hypertension or diabetes, the distribution of performance status, and the distribution of orientation/disorientation, these differences were not statistically significant because of the small number of subjects.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and brain CT findings according to the severity of brain atrophy

| No/mild brain atrophy (n = 27) | Severe brain atrophy (n = 24) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 82 (79–88) | 85 (83–90) | ns |

| Male | 12 (44) | 9 (38) | ns |

| Hypertension | 16 (59) | 10 (42) | ns |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (19) | 1 (4) | ns |

| ECOG Performance status | ns | ||

| 0–2 | 19 (70) | 14 (58) | |

| 3–4 | 8 (30) | 10 (42) | |

| Dementia status | ns | ||

| Oriented | 18 (67) | 12 (50) | |

| Disoriented | 9 (33) | 12 (50) | |

| Major tranquilizer use | 7 (26) | 4 (17) | ns |

| Follow (years) | 3.7 (1.9–4.0) | 2.9 (2.7–3.9) | ns |

| Brain CT findings | |||

| Cortical atrophy, severe | |||

| Frontal lobe | 0 (0) | 21 (88) | <0.001 |

| Parietal lobe | 0 (0) | 18 (75) | <0.001 |

| Temporal lobe | 0 (0) | 10 (42) | <0.001 |

| Occipital lobe | 0 (0) | 3 (13) | <0.001 |

| Four cortical sulci ratio | 0.09 (0.08–0.12) | 0.15 (0.11–0.17) | <0.001 |

| Ventricular dilatation | |||

| Evans ratio | 0.38 (0.35–0.43) | 0.36 (0.32–0.42) | ns |

| Third ventricular ratio | 0.08 (0.06–0.11) | 0.08 (0.06–0.09) | ns |

| White matter lesions, diffuse | |||

| Frontal | 10 (40) | 13 (59) | ns |

| Parieto-occipital | 11 (42) | 12 (57) | ns |

| Temporal | 6 (29) | 4 (31) | ns |

| Lacunar infarction (<2 mm) | ns | ||

| Non | 12 (44) | 8 (33) | |

| Single | 8 (30) | 9 (38) | |

| Multiple | 7 (26) | 7 (29) | |

Notes: Values are n (%) or medians (interquartile range).

χ2 test or Wilcoxon test. Severe brain atrophy was defined as severe atrophy in any of the frontal, temporal, parietal or occipital lobe. Four cortical sulci ratio = the sum of the widths of the four widest sulci at the two highest scanning levels/maximal transversal intracranial width. Evans ratio = maximal frontal horn width/maximal transversal intracranial width. Third ventricular ratio = maximal width of the third ventricle/maximal transversal intracranial width.

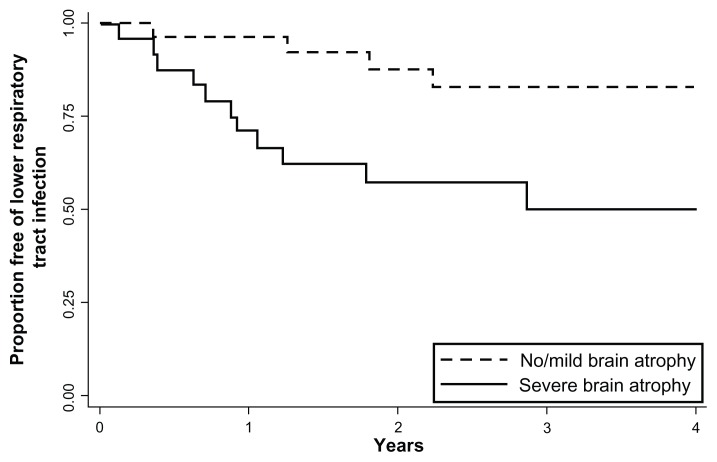

The incidence of LRTI was compared according to the severity of cortical brain atrophy (Table 2). The incidence rate ratio for LRTI was higher in subjects with severe brain atrophy than in those without severe brain atrophy, and was statistically significant after adjustment for known confounding factors (odds ratio 4.60, 95% confidence interval 1.18–17.93, fully adjusted P = 0.028). The incidence rate ratio for LRTI was higher in subjects in the middle (odds ratio 3.88) and upper (odds ratio 2.08) tertiles of the four cortical sulci ratios (an objective scale of cortical atrophy) than in subjects in the lowest tertile, although these associations were not statistically significant. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve showed that the time to the first episode of LRTI was significantly shorter in subjects with severe brain atrophy than in those without (log-rank test, P = 0.019, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Risk of lower respiratory tract infection according to the severity and type of brain atrophy and white matter lesions

| n | Person-years | No of events | Rate/person-years | Adjusted IRRa | 95% CIa | P valuea | Fully adjusted IRRb | 95% CIb | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical atrophy | ||||||||||

| No/mild atrophy | 27 | 84.2 | 7 | 0.08 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Severe atrophy (any lobe) | 24 | 70.3 | 18 | 0.26 | 4.15 | 1.14–15.06 | 0.031 | 4.60 | 1.18–17.93 | 0.028 |

| Frontal lobe | 21 | 61.9 | 16 | 0.26 | 4.46 | 1.12–17.73 | 0.034 | 4.75 | 1.23–18.35 | 0.024 |

| Parietal lobe | 18 | 54.8 | 16 | 0.29 | 4.90 | 1.16–20.77 | 0.031 | 5.23 | 1.32–20.74 | 0.018 |

| Temporal lobe | 10 | 28.5 | 5 | 0.18 | 4.20 | 0.48–36.40 | 0.193 | 3.28 | 0.69–15.62 | 0.136 |

| Four cortical sulci ratio | ||||||||||

| Lower tertile | 16 | 49.9 | 4 | 0.08 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Middle tertile | 17 | 50.7 | 9 | 0.18 | 4.64 | 0.64–33.79 | 0.130 | 3.88 | 0.42–35.61 | 0.230 |

| Upper tertile | 17 | 66.9 | 12 | 0.18 | 2.57 | 0.68–9.64 | 0.162 | 2.08 | 0.42–10.41 | 0.371 |

| Ventricular dilatation | ||||||||||

| Evans ratio | ||||||||||

| Lower tertile | 16 | 50.3 | 9 | 0.18 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Middle tertile | 17 | 44.3 | 12 | 0.27 | 0.71 | 0.30–1.64 | 0.420 | 0.61 | 0.19–1.93 | 0.398 |

| Upper tertile | 17 | 55.9 | 4 | 0.07 | 0.64 | 0.10–4.28 | 0.645 | 0.33 | 0.12–2.32 | 0.173 |

| Third ventricular ratio | ||||||||||

| Lower tertile | 17 | 49.4 | 12 | 0.24 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Middle tertile | 17 | 51.4 | 10 | 0.19 | 0.55 | 0.15–1.97 | 0.360 | 0.88 | 0.29–2.66 | 0.821 |

| Upper tertile | 16 | 49.7 | 3 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.06–1.26 | 0.096 | 0.38 | 0.09–1.49 | 0.164 |

| White matter lesions | ||||||||||

| No/focal/confluence | 24 | 70.1 | 12 | 0.17 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Diffuse (any region) | 27 | 84.4 | 13 | 0.15 | 1.07 | 0.30–3.84 | 0.919 | 1.40 | 0.39–5.05 | 0.608 |

| Frontal | 41 | 71.3 | 13 | 0.18 | 1.22 | 0.35–4.32 | 0.754 | 1.57 | 0.43–5.77 | 0.496 |

| Parieto-occipital | 38 | 68.8 | 11 | 0.16 | 1.28 | 0.30–5.44 | 0.739 | 1.38 | 0.34–5.61 | 0.655 |

| Temporal | 23 | 24.0 | 4 | 0.17 | 1.49 | 0.28–8.06 | 0.643 | 1.03 | 0.15–6.97 | 0.974 |

Notes:

Adjusted for age and sex;

adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, mobility status by ECOG performance status (0–2 and 3–4), dementia status (oriented or not), major tranquilizer use, and lacunar infarction (non, single, and multiple). Severe brain atrophy was defined as severe atrophy in any of the frontal, temporal, parietal or occipital lobes. Four cortical sulci ratio = the sum of the widths of the four widest sulci at the two highest scanning levels/maximal transversal intracranial width. Evans ratio = maximal frontal horn width/maximal transversal intracranial width. Third ventricular ratio = maximal width of the third ventricle/maximal transversal intracranial width.

Abbreviations: IRR, incidence rate ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for the first episode of lower respiratory tract infection according to severity of brain atrophy.

The incidence of LRTI was then compared according to the type of brain atrophy and the presence of diffuse white matter lesions (Table 2). The incidence rate ratios for LRTI were significantly greater in patients with frontal or parietal lobe atrophy. In contrast, there were no differences in the incidence of LRTI among patients with temporal lobe atrophy, ventricular dilatation, or diffuse white matter lesions.

Discussion

We found that elderly subjects with severe cortical brain atrophy, a marker for neurodegeneration and which might increase the risk of dysphagia, were at significantly greater risk of developing LRTI. The time to the first episode of LRTI was also significantly shorter in subjects with severe brain atrophy.

Elderly people are particularly susceptible to LRTI, including pneumonia, and LRTI is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in long-term care facilities.12,13 Dysphagia and the inability to take oral medications, a sign of dysphagia, are all established causes of aspiration pneumonia.6,14 Dysphagia is also frequent in patients with pseudobulbar palsy following brain damage, including cortex, basal ganglia, and brain stem infarctions.15 Silent brain infarction without apparent signs of pseudobulbar palsy is also a risk factor for pneumonia,16 possibly because of an impaired swallowing reflex and silent aspiration during sleep (nocturnal microaspiration).17,18

Evaluation of swallowing by videofluoroscopy, a gold standard swallowing test, is not easily accessible for nursing home residents, and bedside evaluation of swallowing does not always show high sensitivity in detecting aspiration.19 Brain stem infarction, which increases the risk of dysphagia, is difficult to evaluate solely by brain CT, and nursing home residents have limited access to magnetic resonance imaging. Thus, other methods that can be used to determine the risk of respiratory infection would be beneficial.

Brain atrophy and white matter lesions are frequently observed on CT images of elderly subjects,1 but their clinical consequences are generally unknown. Brain atrophy, a marker of neurodegeneration,2,3 represents the process of dementia, which is a well known risk factor for pneumonia and aspiration.20 White matter lesions represent subcortical vascular disease and incomplete infarcts.21 Preliminary data have indicated that brain atrophy and white matter lesions might be associated with dysphagia. For example, elderly subjects with brain atrophy had lower swallowing pressure than did subjects without brain atrophy,5 while subjects with white matter lesions had a longer swallowing duration.22 Patients with progressive cortical atrophy of the frontal lobe often have anterior opercular syndrome, which may result in dysphagia and subsequent aspiration pneumonia.4 Our finding that subjects with severe brain atrophy were more susceptible to LRTI supports our hypothesis that brain atrophy represents neurodegeneration resulting in dysphagia and silent aspiration,4,5 and dysphagia and silent aspiration may cause aspiration pneumonia.6,14 Because aspiration is the major cause of pneumonia in elderly individuals (in 71% of cases in elderly subjects versus 10% of cases in non-elderly subjects),23 and because we cannot differentiate between aspiration pneumonia and other types of pneumonia based on symptoms or chest x-ray,34 we included all LRTI in this study. If it was possible to differentiate aspiration pneumonia, we suspect that the difference in frequency of respiratory infection between subjects with and without brain atrophy might be greater.

Frontal and parietal lobe atrophy carried an increased risk for LRTI, whereas temporal lobe atrophy, ventricular dilatation and white matter lesions showed no differences in risk of LRTI. The frontoparietal operculum is a functional component involved in swallowing.25,26 Involvement of the precentral gyrus or the inferior frontal gyrus of the frontal lobe have been reported to disturb swallowing,27,28 and anterior opercular syndrome caused by inferior frontal gyrus involvement results in dysphagia.4 Alternatively, involvement of the supramarginal gyrus of the inferior parietal lobule causes swallowing apraxia,29 and sensory impairment in the laryngopharynx caused by parietal lobe involvement contributes to the development of dysphagia.30 It is interesting to note that patients with frontotemporal lobar dementia were often dysphagic before the development of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.31 We did not find evidence in our study that white matter lesions increase the risk of LRTI, although Binswanger’s disease, which presents with severe white matter lesions, is associated with dysphagia.32 This might be explained by the finding that pseudobulbar palsy in Binswanger’s disease is a marker for frontal lobe syndrome.33 Ventricular dilatation and white matter lesions may be a collateral phenomenon determined by the physiologic processes of aging.2,34

One limitation of this study is that we have limited data from chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia independently of LRTI, because chest radiographs were not obtained in subjects with LRTI if their oxygen saturation was preserved, in accordance with established clinical guidelines. 11,24 Other studies, like ours, define LRTI based on clinical symptoms alone.12,14 We evaluated radiographically confirmed pneumonia for subjects with radiographic data, and the incidence rate ratios of pneumonia were higher in subjects with severe brain atrophy, frontal lobe atrophy, and parietal lobe atrophy, compared with those in subjects without severe brain atrophy, although these rates were not statistically different because of the small number of events (data not shown). Furthermore, we did not consider microbial test results, because it is difficult to differentiate between infective sources and indigenous bacteria, particularly in elderly subjects, and the sensitivity and specificity of microbial findings are low.35

Another limitation is that we did not evaluate swallowing function. Our study subjects showed no apparent signs of dysphagia, because they could eat and drink without coughing, thus passing the Bedside Swallow Assessment and water swallowing test.36 Therefore, our assessment of brain atrophy as a risk factor for LRTI is useful in subjects without apparent signs of dysphagia. It is possible that these subjects experience silent aspiration during sleep, as has been observed in other studies.17,18

Unfortunately, we did not perform detailed neurological tests at the time of brain CT because of severe dementia in approximately half of our subjects, although no apparent neurologic deficits were observed in any subject; thus, we could not assess whether there were differences in neurological signs, such as Parkinsonism, which contributes to swallowing function, in our subjects. It is possible that differences between subjects with and without severe brain atrophy might depend on the presence of neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, which is associated with cortical atrophy, or normal pressure hydrocephalus, which is associated with ventricular dilatation, although this could not be evaluated.

We conducted this as an exploratory study to identify possible risk factors for respiratory infection. Because of the small sample size, some of the observed associations may be false positives. Another study with a larger number of subjects is needed to confirm our findings. In addition, stratified analyses by baseline characteristics are needed. We stratified the subjects according to ECOG performance status (0–2 and 3–4) and age (<80 and ≥80 years). The incidence rate ratios for ECOG 0–2 and 3–4 were 2.59 and 4.55, respectively, while those for age < 80 and ≥80 years were 5.79 and 9.72, respectively. However, these were not statistically significant because of the small number of subjects. Therefore, again, the results should be confirmed in larger studies. It is also warranted to elucidate the mechanism by which brain atrophy increases the risk of respiratory infection.

The use of CT imaging is increasing worldwide, and there are several situations in which brain CT scans are routinely performed in elderly subjects (eg, evaluation of dementia and minor head injury). Although we do not advocate brain CT just to assess the risk of LRTI, we do suggest that brain CT scans taken for other purposes should be evaluated to determine the risk of subsequent LRTI, which has a high risk of mortality in nursing home residents.

Conclusion

We found that elderly subjects with severe brain atrophy are more susceptible to LRTI including pneumonia, possibly reflecting neurodegeneration, and resulting in dysphagia and silent aspiration. Assessing the severity of brain atrophy might help us to identify elderly subjects at increased risk of respiratory infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hiromi Ito, Kayoko Hayashi, Kazue Uesaka, Harumi Murata, Harumi Hayashi, and Harumi Matsumoto for their assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Simoni M, Pantoni L, Pracucci G, et al. Prevalence of CT-detected cerebral abnormalities in an elderly Swedish population sample. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;118(4):260–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid AT, van Norden AG, de Laat KF, et al. Patterns of cortical degeneration in an elderly cohort with cerebral small vessel disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31(12):1983–1992. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holtzman DM, Li YW, DeArmond SJ, et al. Mouse model of neurodegeneration: atrophy of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in trisomy 16 transplants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(4):1383–1387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broussolle E, Bakchine S, Tommasi M, et al. Slowly progressive anarthria with late anterior opercular syndrome: a variant form of frontal cortical atrophy syndromes. J Neurol Sci. 1996;144(1/2):44–58. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(96)00096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins J, Levine R, Wood J, Roecker EB, Luschei E. Age effects on lingual pressure generation as a risk factor for dysphagia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(5):M257–M262. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.5.m257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann G, Hankey GJ, Cameron D. Swallowing function after stroke: prognosis and prognostic factors at 6 months. Stroke. 1999;30(4):744–748. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Leon MJ, Ferris SH, George AE, Reisberg B, Kricheff II, Gershon S. Computed tomography evaluations of brain-behavior relationships in senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Neurobiol Aging. 1980;1(1):69–79. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(80)90027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Londos E, Minthon L, et al. Usefulness of computed tomography linear measurements in diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Radiol. 2008;49(1):91–97. doi: 10.1080/02841850701753706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahlund LO, Barkhof F, Fazekas F, et al. European Task Force on Age-Related White Matter Changes. A new rating scale for age-related white matter changes applicable to MRI and CT. Stroke. 2001;32(6):1318–1322. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.6.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGeer A, Campbell B, Emori TG, et al. Definitions of infection for surveillance in long-term care facilities. Am J Infect Control. 1991;19(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(91)90154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.High KP, Bradley SF, Gravenstein S, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America: clinical practice guideline for the evaluation of fever and infection in older adult residents of long-term care facilities: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(3):375–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vergis EN, Brennen C, Wagener M, Muder RR. Pneumonia in long-term care: a prospective case-control study of risk factors and impact on survival. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(19):2378–2381. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.19.2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koch AM, Eriksen HM, Elstrøm P, Aavitsland P, Harthug S. Severe consequences of healthcare-associated infections among residents of nursing homes: a cohort study. J Hosp Infect. 2009;71(3):269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loeb M, McGeer A, McArthur M, Walter S, Simor AE. Risk factors for pneumonia and other lower respiratory tract infections in elderly residents of long-term care facilities. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(17):2058–2064. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.17.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Besson G, Bogousslavsky J, Regli F, Maeder P. Acute pseudobulbar or suprabulbar palsy. Arch Neurol. 1991;48(5):501–507. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530170061021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakagawa T, Sekizawa K, Nakajoh K, Tanji H, Arai H, Sasaki H. Silent cerebral infarction: a potential risk for pneumonia in the elderly. J Intern Med. 2000;247(2):255–259. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakagawa T, Sekizawa K, Arai H, Kikuchi R, Manabe K, Sasaki H. High incidence of pneumonia in elderly patients with basal ganglia infarction. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(3):321–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinto A, Yanai M, Nakagawa T, Sekizawa K, Sasaki H. Swallowing reflex in the night. Lancet. 1994;344(8925):820–821. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Splaingard ML, Hutchins B, Sulton LD, Chaudhuri G. Aspiration in rehabilitation patients: videofluoroscopy vs bedside clinical assessment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69(8):637–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sura L, Madhavan A, Carnaby G, Crary MA. Dysphagia in the elderly: management and nutritional considerations. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:287–298. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S23404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du AT, Schuff N, Chao LL, et al. White matter lesions are associated with cortical atrophy more than entorhinal and hippocampal atrophy. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(4):553–559. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine R, Robbins JA, Maser A. Periventricular white matter changes and oropharyngeal swallowing in normal individuals. Dysphagia. 1992;7(3):142–147. doi: 10.1007/BF02493446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kikuchi R, Watabe N, Konno T, Mishina N, Sekizawa K, Sasaki H. High incidence of silent aspiration in elderly patients with community- acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(1):251–253. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.1.8025758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim WS, Baudouin SV, George RC, et al. Pneumonia Guidelines Committee of the BTS Standards of Care Committee: BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax. 2009;64(Suppl 3):iii1–55. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.121434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toogood JA, Barr AM, Stevens TK, Gati JS, Menon RS, Martin RE. Discrete functional contributions of cerebral cortical foci in voluntary swallowing: a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) “Go, No-Go” study. Exp Brain Res. 2005;161(1):81–90. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-2048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teismann IK, Suntrup S, Warnecke T, et al. Cortical swallowing processing in early subacute stroke. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meadows JC. Dysphagia in unilateral cerebral lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1973;36(5):853–860. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.36.5.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin RE, Sessle BJ. The role of the cerebral cortex in swallowing. Dysphagia. 1993;8(3):195–202. doi: 10.1007/BF01354538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daniels SK. Swallowing apraxia: a disorder of the Praxis system? Dysphagia. 2000;15(3):159–166. doi: 10.1007/s004550010019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aviv JE, Martin JH, Sacco RL, et al. Supraglottic and pharyngeal sensory abnormalities in stroke patients with dysphagia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105(2):92–97. doi: 10.1177/000348949610500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langmore SE, Olney RK, Lomen-Hoerth C, Miller BL. Dysphagia in patients with frontotemporal lobar dementia. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(1):58–62. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olsen CG, Clasen ME. Senile dementia of the Binswanger’s type. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(9):2068–2074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santamaria Ortiz J, Knight PV. Review: Binswanger’s disease, leukoaraiosis and dementia. Age Ageing. 1994;23(1):75–81. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poloni M, Mascherpa C, Faggi L, Rognone F, Gozzoli L. Cerebral atrophy in motor neuron disease evaluated by computed tomography. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1982;45(12):1102–1105. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.45.12.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engelhart ST, Hanses-Derendorf L, Exner M, Kramer MH. Prospective surveillance for healthcare-associated infections in German nursing home residents. J Hosp Infect. 2005;60(1):46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smithard DG, O’Neill PA, Park C, et al. North West Dysphagia Group. Can bedside assessment reliably exclude aspiration following acute stroke? Age Ageing. 1998;27(2):99–106. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]