Abstract

AIM: To investigate the predictive factors of lymph node metastasis (LNM) in poorly differentiated early gastric cancer (EGC), and enlarge the possibility of using laparoscopic wedge resection (LWR).

METHODS: We retrospectively analyzed 85 patients with poorly differentiated EGC who underwent surgical resection between January 1992 and December 2010. The association between the clinicopathological factors and the presence of LNM was retrospectively analyzed by univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. Odds ratios (OR) with 95%CI were calculated. We further examined the relationship between the positive number of the three significant predictive factors and the LNM rate.

RESULTS: In the univariate analysis, tumor size (P = 0.011), depth of invasion (P = 0.007) and lymphatic vessel involvement (P < 0.001) were significantly associated with a higher rate of LNM. In the multivariate model, tumor size (OR = 7.125, 95%CI: 1.251-38.218, P = 0.041), depth of invasion (OR = 16.624, 95%CI: 1.571-82.134, P = 0.036) and lymphatic vessel involvement (OR = 39.112, 95%CI: 1.745-123.671, P = 0.011) were found to be independently risk clinicopathological factors for LNM. Of the 85 patients diagnosed with poorly differentiated EGC, 12 (14.1%) had LNM. The LNM rates were 5.7%, 42.9% and 57.1%, respectively in cases with one, two and three of the risk factors respectively in poorly differentiated EGC. There was no LNM in 29 patients without the three risk clinicopathological factors.

CONCLUSION: LWR alone may be sufficient treatment for intramucosal poorly differentiated EGC if the tumor is less than or equal to 2.0 cm in size, and when lymphatic vessel involvement is absent at postoperative histological examination.

Keywords: Poorly differentiated early gastric cancer, Early gastric cancer, Lymph node metastasis, Clinicopathological characteristics, Laparoscopic wedge resection

INTRODUCTION

Local resection for early gastric caner (EGC) was first reported by Kitaoka et al[1] in 1984. Laparoscopic wedge resection (LWR) is a procedure based on local resection. This minimally invasive technique can be applied for the management of EGC without the risk of lymph node metastases (LNM)[2-7]. The application of LWR has been limited to differentiated EGC because of the higher risk of lymph node metastases in undifferentiated EGC, compared to differentiated EGC[8,9]. Therefore, gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy has been considered to be an essential treatment for patients with undifferentiated EGC. Undifferentiated carcinoma of gastric cancer includes poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma[10]. However, almost all (96.6%) surgical cases of poorly differentiated EGC confined to the mucosa, have been found not to have LNM[11], suggesting that gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy may be over-treatment for these cases.

Therefore, we carried out this retrospectively study to determine the clinicopathological factors that are predictive of LNM in poorly differentiated EGC. Furthermore, we established a simple criterion to expand the possibility of using LWR for the treatment of poorly differentiated EGC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients underwent a radical operation due to EGC in the Department of Oncology, Affiliated Xing Tai People’s Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Xingtai, China between January 1992 and December 2010 were included in the screening for identification of cases with EGC in this retrospective study.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) lymph node dissection beyond limited (D1) dissection was performed; (2) the resected specimens and lymph nodes were pathologically analyzed, and poorly differentiated EGC was diagnosed, according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma (JCGC)[10]; and (3) patient’s medical records were available in the database.

During the 18 years, 85 patients (60 male, 25 female; mean age 52 years, range: 29-82 years) with histopathologically poorly differentiated tumor were identified to meet the inclusion criteria for further analysis in this study.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hebei Medical University.

Dissection and classification of lymph nodes

Lymph nodes of each case were meticulously dissected from the enbloc specimens, and the classification of the dissected lymph nodes was determined by a surgeon after he/she who carefully reviewed the excised specimens based on the JCGC[10]. Briefly, lymph nodes were classified into group 1 (perigastric lymph nodes) and groups 2 (lymph nodes along the left gastric artery, the common hepatic artery, and the splenic artery and around the celiac axis)[10].

Assessment and classification of lymph node metastasis

Then, the resected lymph nodes were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined by pathologists for metastasis and lymphatic vessel involvement (LVI).

Association between clinicopathological parameters and lymph node metastasis

Clinicopathological parameters that are covered in the JCGC[10] were included in this study. They were the gender (male and female), age (< 60 years, ≥ 60 years), family medical history of gastric cancer, number of tumors (single or multitude), the location of the tumor (upper, middle, or lower of the stomach), tumor size (maximum dimension ≤ 2 cm, or > 2 cm), macroscopic type [protruded (type I), superficial elevated (type IIa), flat (type IIb), superficial depressed (type IIc), or excavated (type III)], depth of invasion (mucosa, submucosa), lymphatic vessel involvement.

The associations between various clinicopathological factors and LNM were examined as described below.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 15.0 statistical software (Chicago, IL, United States). The differences in the clinicopathological parameters between patients with and without LNM were determined by the χ2 test. A multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed subsequently in order to identify independent risk factors for LNM. Hazard ratio and 95%CI were calculated. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 85 patients diagnosed with poorly differentiated EGC, 12 (14.1%) had LNM. As shown in Table 1, 8 (70.6%) were male and 13.3% of them had LNM.

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of potential risk characteristics for lymph node metastasis n (%)

| Factor | Lymph node metastasis | P value |

| Sex | ||

| Male (n = 60) | 8 (13.3) | 0.781 |

| Female (n = 25) | 4 (16.0) | |

| Age (yr) | ||

| < 60 (n = 76) | 10 (13.2) | 0.534 |

| ≥ 60 (n = 9) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Family medical history | ||

| Positive (n = 3) | 0 (0) | 0.509 |

| Negative (n = 82) | 12 (14.6) | |

| Number of tumors | ||

| Single (n = 83) | 12 (14.5) | 0.591 |

| Multitude (n = 2) | 0 (0) | |

| Location | ||

| Upper (n = 20) | 4 (20.0) | 0.566 |

| Middle (n = 5) | 0 (0) | |

| Lower (n = 60) | 8 (13.3) | |

| Tumor size in diameter | ||

| ≤ 2 cm (n = 54) | 3 (5.6) | 0.011 |

| > 2 cm (n = 31) | 9 (29.0) | |

| Macroscopic type | ||

| I (n = 2) | 0 | 0.768 |

| II (n = 64) | 10 (15.6) | |

| III (n = 19) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Depth of invasion | ||

| Mucosa (n = 56) | 3 (5.4) | 0.007 |

| Submucosa (n = 29) | 9 (31.0) | |

| Lymphatic vessel involvement | ||

| Positive (n = 14) | 8 (57.1) | < 0.001 |

| Negative (n = 71) | 4 (5.6) | |

Association between clinicopathological factors and lymph node metastasis

The association between various clinicopathological factors and LNM was first analyzed by the χ2 test (Table 1). A tumor larger than 2.0 cm, submucosal invasion, and the presence of LVI were significantly associated with a higher rate of LNM (all P < 0.05). However, gender, age, family medical history of gastric cancer, number, location, and macroscopic type were found not to be associated with LNM.

Multivariate analysis of potential independent risk clinicopathological factors for lymph node metastasis

The three characteristics that were significantly associated with LNM by univariate analysis were found to be significant and independent risk factors for LNM by multivariate analysis (both P < 0.05, Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of potential risk factors for lymph node metastasis

| Characteristics | Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| Tumor size | 7.125 | 1.251-38.218 | 0.041 |

| ≤ 2 cm | |||

| > 2 cm | |||

| Depth of invasion | 16.624 | 1.571-82.134 | 0.036 |

| Mucosa | |||

| Submucosa | |||

| Lymphatic vessel involvement | 39.112 | 1.745-123.671 | 0.011 |

| Positive | |||

| Negative |

Lymph node metastasis in poorly differentiated EGC

The LNM rates were 5.7%, 42.9% and 57.1%, respectively in cases with one, two and three of the risk factors respectively in poorly differentiated EGC. There was no LNM in 29 patients without the three risk clinicopathological factors.

DISCUSSION

Because an increased rate of accurate diagnosis of EGC, which in turn leads to an improved prognosis, an increased interest has been focused on the improvement of the quality of life and minimization of invasive procedures[12-14]. LWR has been associated with less pain, quicker return of gastrointestinal function, better pulmonary function, decreased stress response, a shorter hospital stay and better postoperative quality of life than open gastrectomy[15-19]. If the feasibility and safety of LWR in the treatment of EGC has been proven, it is also true that several reports have shown the efficacy of LWR in the cure of EGC with results comparable to those of an open gastrectomy[20].

One of the critical factors in choosing LWR for EGC would be the precise prediction of whether the patient has LNM or not. To achieve this goal, several studies have attempted to identify risk factors predictive of LNM in EGC. Few reports, however, have focused on the applicability of laparoscopic treatment for poorly differentiated EGC.

The present multivariate analysis revealed that a tumor larger than 2.0 cm, submucosal invasion, and the presence of LVI were significant predictive factors for LNM in patients with poorly differentiated EGC. Our results together with the previous reports on undifferentiated EGC[21-24] demonstrated a significant correlation between the high incidence of LNM and a tumor larger than 2.0 cm submucosal invasion, or presence of LVI[25-27].

We then attempted to identify a subgroup among poorly differentiated EGC patients in whom the risk of LNM can be largely ruled out, i.e., candidates who can be curably treated by LWR. As a result, we found no LNM in patients with intramucosal cancer if the tumor is less than or equal to 2.0 cm in size without LVI. This may indicate that LWR could be sufficient to treat these cases, and that additional surgery is unnecessary.

We further examined the relationship between the positive number of the three significant predictive factors and the LNM rate in order to establish a simple criterion for an optimal strategy for treatment of poorly differentiated EGC. In the present study, the LNM rates were 5.7%, 42.9% and 57.1%, respectively in cases with one, two and three of the risk factors respectively in poorly differentiated EGC. Therefore, gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy is probably better for these patients with the risk factors.

However, there are some limitations in this study. First, this is a retrospective analysis. Second, the sample size is relatively small. Thus, the outcomes of the study may not be good enough to expose the truth.

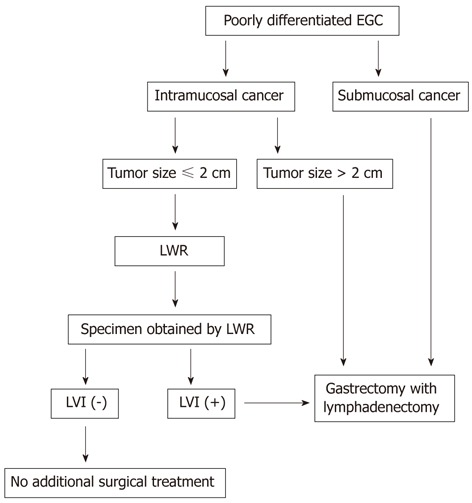

According to our study, we would propose a treatment strategy for patients with poorly differentiated EGC (Figure 1). These predictive factors (tumor size and depth of invasion) were diagnosed by endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound. The particular presence of LVI becomes first evident after the histological assessment of the entire specimen obtained by LWR. LWR alone may be a sufficient treatment for intramucosal poorly differentiated EGC if the tumor is less than or equal to 2.0 cm in size, and when LVI is absent at postoperative histological examination. When specimens show with LVI, an additional gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy should be recommended.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the therapeutic strategy for cases with poorly differentiated early gastric cancer. EGC: Early gastric cancer; LWR: Laparoscopic wedge resection; LVI: Lymphatic vessel involvement.

COMMENTS

Background

Gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy is the standard therapy for poorly differentiated early gastric cancer (EGC) with lymph node metastasis (LNM). However, because approximately 96.6% of in poorly differentiated intramucosal EGC have no LNM, gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy may be an over-treatment for such patients. The authors attempted to identify a subgroup of poorly differentiated EGC patients in whom the risk of LNM can be ruled out and treated them with laparoscopic wedge resection (LWR), which may serve as a breakthrough treatment of poorly differentiated EGC.

Research frontiers

Several studies have attempted to identify risk factors predictive of LNM in EGC. Few reports, however, have focused on the applicability of laparoscopic treatment for poorly differentiated EGC.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Tumor size, depth of invasion and lymphatic vessel involvement were found to be independently risk clinicopathological factors for LNM in poorly differentiated EGC. Furthermore, the authors established a simple criterion to expand the possibility of using LWR for the treatment of poorly differentiated EGC.

Applications

Based on the predictive factors for LNM, LWR is the treatment of choice for poorly differentiated EGC.

Terminology

LWR is a procedure based on local resection and a method of minimally invasive technique.

Peer review

This study analyzed the data from 85 patients with poorly differentiated EGC. They concluded that tumor size, depth of invasion and lymphatic vessel involvement are the significant risk factors for LNM. This is a well-designed retrospective study.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Dr. Guang-Wen Cao, MD, PhD, Professor and Chairman, Department of Epidemiology, the Second Military Medical University, 800 Xiangyin Road, Shanghai 200433, China; Elfriede Bollschweiler, Professor, Department of Surgery, University of Cologne, Kerpener Strabe 62, 50935 Köln, Germany; Dr. Wei-Dong Tong, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Daping Hospital, Third Military Medical University, Chongqing 400042, China

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Kitaoka H, Yoshikawa K, Hirota T, Itabashi M. Surgical treatment of early gastric cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1984;14:283–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koeda K, Nishizuka S, Wakabayashi G. Minimally invasive surgery for gastric cancer: the future standard of care. World J Surg. 2011;35:1469–1477. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nozaki I, Kubo Y, Kurita A, Tanada M, Yokoyama N, Takiyama W, Takashima S. Long-term outcome after laparoscopic wedge resection for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2665–2669. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9795-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Etoh T, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Laparoscopic gastrectomy for cancer. Dig Dis. 2005;23:113–118. doi: 10.1159/000088592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitano S, Shiraishi N. Current status of laparoscopic gastrectomy for cancer in Japan. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:182–185. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8820-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida K, Yamaguchi K, Okumura N, Osada S, Takahashi T, Tanaka Y, Tanabe K, Suzuki T. The roles of surgical oncologists in the new era: minimally invasive surgery for early gastric cancer and adjuvant surgery for metastatic gastric cancer. Pathobiology. 2011;78:343–352. doi: 10.1159/000328197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fatourou E, Roukos DH. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: can it safely expand indications for a minimally invasive approach to patients with early gastric cancer? Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1793–1794; author reply 1795. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0844-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyung WJ, Cheong JH, Kim J, Chen J, Choi SH, Noh SH. Application of minimally invasive treatment for early gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2004;85:181–185; discussion 186. doi: 10.1002/jso.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Guidelines for the treatment of gastric cancer [M]. 2nd ed. Tokyo: Kane-hara; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma - 2nd English Edition - Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24. doi: 10.1007/s101209800016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park YD, Chung YJ, Chung HY, Yu W, Bae HI, Jeon SW, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO. Factors related to lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic mucosal resection for treating poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Endoscopy. 2008;40:7–10. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitagawa Y, Kitano S, Kubota T, Kumai K, Otani Y, Saikawa Y, Yoshida M, Kitajima M. Minimally invasive surgery for gastric cancer--toward a confluence of two major streams: a review. Gastric Cancer. 2005;8:103–110. doi: 10.1007/s10120-005-0326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DY, Joo JK, Ryu SY, Kim YJ, Kim SK. Factors related to lymph node metastasis and surgical strategy used to treat early gastric carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:737–740. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i5.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sung CM, Hsu CM, Hsu JT, Yeh TS, Lin CJ, Chen TC, Su MY, Chiu CT. Predictive factors for lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5252–5256. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i41.5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ludwig K, Klautke G, Bernhard J, Weiner R. Minimally invasive and local treatment for mucosal early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1362–1366. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-2249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SW, Nomura E, Bouras G, Tokuhara T, Tsunemi S, Tanigawa N. Long-term oncologic outcomes from laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a single-center experience of 601 consecutive resections. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang JL, Wei HB, Zheng ZH, Chen TF, Huang Y, Wei B, Guo WP, Hu BG. [Comparison of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with open gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer] Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Zazhi. 2012;15:615–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng YK, Yang ZL, Peng JS, Lin HS, Cai L. Laparoscopy-assisted versus open distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: evidence from randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials. Ann Surg. 2012;256:39–52. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182583e2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pavlidis TE, Pavlidis ET, Sakantamis AK. The role of laparoscopic surgery in gastric cancer. J Minim Access Surg. 2012;8:35–38. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.95524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto S. Stomach cancer incidence in the world. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2001;31:471. doi: 10.1093/jjco/31.9.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li C, Kim S, Lai JF, Oh SJ, Hyung WJ, Choi WH, Choi SH, Zhu ZG, Noh SH. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in undifferentiated early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:764–769. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9707-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, Kato Y. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219–225. doi: 10.1007/pl00011720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abe N, Watanabe T, Suzuki K, Machida H, Toda H, Nakaya Y, Masaki T, Mori T, Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Risk factors predictive of lymph node metastasis in depressed early gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2002;183:168–172. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00860-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichikura T, Uefuji K, Tomimatsu S, Okusa Y, Yahara T, Tamakuma S. Surgical strategy for patients with gastric carcinoma with submucosal invasion. A multivariate analysis. Cancer. 1995;76:935–940. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950915)76:6<935::aid-cncr2820760605>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sano T, Kobori O, Muto T. Lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: endoscopic resection of tumour. Br J Surg. 1992;79:241–244. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maehara Y, Orita H, Okuyama T, Moriguchi S, Tsujitani S, Korenaga D, Sugimachi K. Predictors of lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1992;79:245–247. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu C, Lu P, Lu Y, Xu H, Wang S, Chen J. Clinical implications of metastatic lymph node ratio in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]