Abstract

Extrathoracic solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs) have been described at almost every anatomic location of human body, but reports of SFT in the abdominal cavity are rare. We herein present a rare case of SFT originating from greater omentum. Computed tomography revealed a 15.8 cm × 21.0 cm solid mass located at superior aspect of stomach. Open laparotomy confirmed its mesenchymal origin. Microscopically, its tissue was composed of non-organized and spindle-shaped cells exhibiting atypical nuclei, which were divided up by branching vessel and collagen bundles. Immunohistochemical staining showed that this tumor was negative for CD117, CD99, CD68, cytokeratin, calretinin, desmin, epithelial membrane antigen, F8 and S-100, but positive for CD34, bcl-2, α-smooth muscle actin and vimentin. The patient presented no evidence of recurrence during follow-up. SFT arising from abdominal cavity can be diagnosed by histological findings and immunohistochemical markers, especially for CD34 and bcl-2 positive cases.

Keywords: Greater omentum, Solitary fibrous tumor, Immunohistochemical markers

INTRODUCTION

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT), a rare neoplasm occurring most often in the visceral pleura, was first described by Klemperer and Rabin in 1931[1]. Extrathoracic SFT has been described at almost every anatomic location of the human body[2-6], but reports of SFT in the abdominal cavity are rare[7-11]. Five SFT cases involving omentum have been reported up till December 2011[11-15]. Herein, we report a rare case of a giant SFT originating from greater omentum. The final diagnosis of the patient was established by pathological examination and immunohistochemical study after an open excision of the tumor.

CASE REPORT

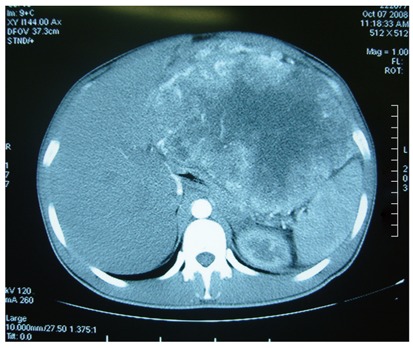

A 29-year-old Chinese man was admitted to the Subei People’s Hospital of Jiangsu Province, China on July 1, 2008. He complained of a mass in the upper abdomen and a gradual weight loss that started more than four months ago. He was a farmer. He had remained well until the day before admission, with no fever, no vomiting and no stomach-ache except for epigastric discomfort and compression. Physical examination showed a large abdominal mass lying between xiphoid process of the sternum and umbilicus without obvious tenderness. No abnormalities were found in laboratory data including tumor markers (Table 1). Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed extrinsic multi-organ compression due to a giant solitary tumor of 15.8 cm × 21.0 cm occupying the majority of abdominal cavity (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Laboratory findings on admission

| Tumor markers | Index | Normal range |

| CA199 (KU/L) | 5.47 | < 35.00 |

| CA242 (KU/L) | 1.31 | < 20.00 |

| CA125 (KU/L) | 2.27 | < 35.00 |

| CA15-3 (KU/L) | 2.28 | < 35.00 |

| NSE (ng/mL) | < 1.0 | < 13.00 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 1.21 | < 5.00 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 27.13 | < 322.00 |

| β-HCG (MIU/mL) | < 0.02 | < 3.00 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 0.88 | < 20.00 |

| Free-PSA (ng/mL) | < 0.22 | < 1.00 |

| PSA (ng/mL) | < 0.04 | < 5.00 |

| HGH (ng/mL) | 2.15 | < 7.50 |

CA: Cancer antigen; NSE: Neuron-specific enolase; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; β-HCG: β-human chorionic gonagotropin; AFP: Alphafetoprotein; PSA: Prostate specific antigen; HGH: Human growth hormone.

Figure 1.

Abdominal computed tomography demonstrating a giant solitary tumor of 15.8 cm × 21.0 cm in abdominal cavity.

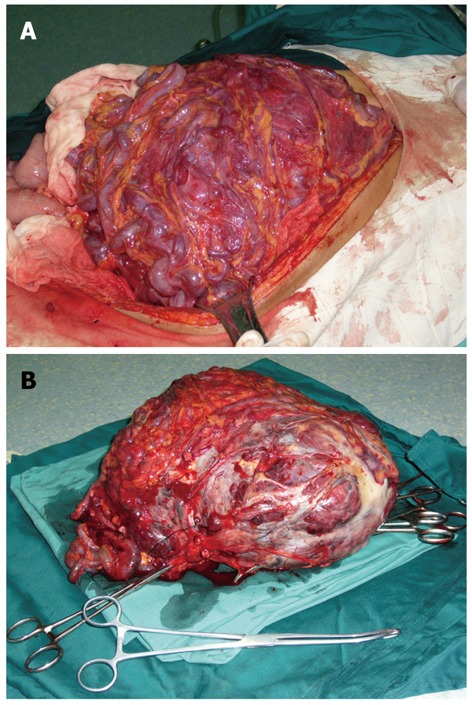

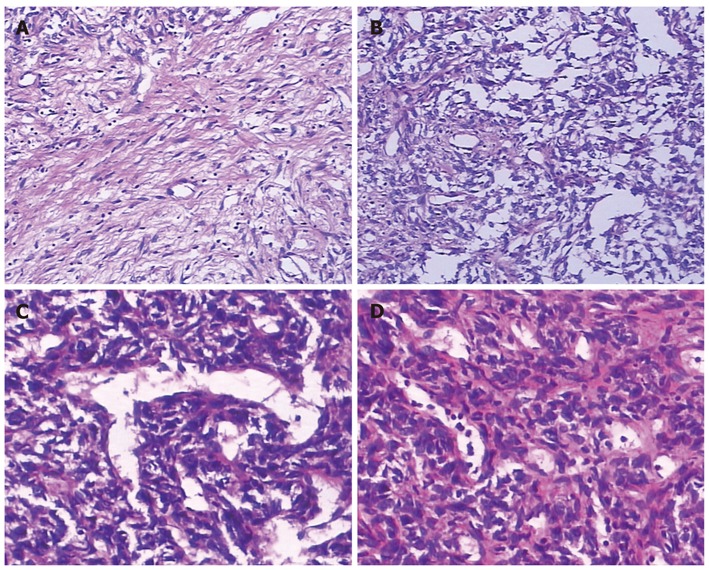

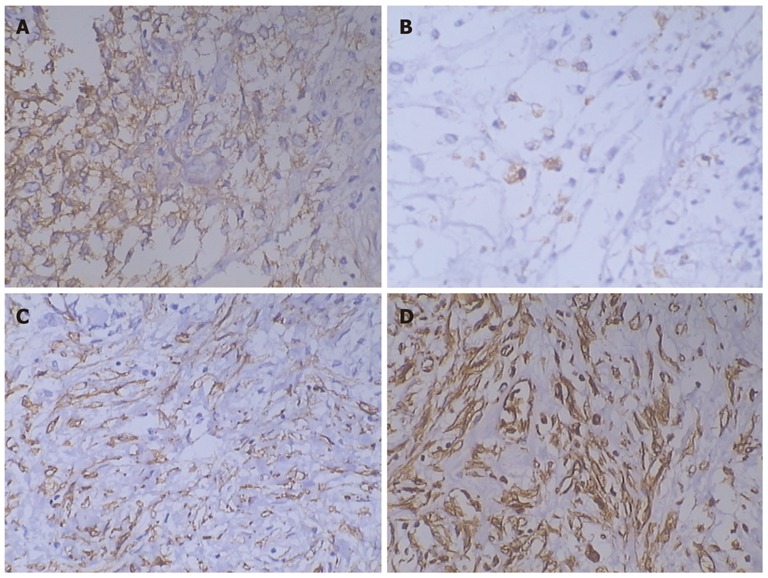

Laparotomy was performed and a giant tumor originating from greater omentum was discovered. The tumor was partly surrounded by greater omentum, and tightly adhered to the spleen and stomach (Figure 2). Abundant and extremely expanded blood vessels of greater omentum were present along the surface of tumor, leading to a blood loss of nearly 2000 mL when the tumor was totally excised. The excised mass was solitary and tenacious compassed with a complete envelope. The mass measured 28 cm × 25 cm × 11 cm in size and 5002.4 g in weight. Microscopically, the excised tumor tissue was composed of non-organized and spindle-shaped cells exhibiting atypical nuclei, which were divided up by branching vessel and collagen bundles (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical staining showed that the tumor was negative for CD117, CD99, CD68, cytokeratin, calretinin, desmin, epithelial membrane antigen, F8 and S-100, but positive for CD34, bcl-2, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and vimentin (VIM) (Figure 4). According to the mitotic index, this case was considered to have a low risk of malignancy. The patient experienced no postoperative complications, and was discharged 10 d after surgery. During a 48-moSS follow-up by ultrasonography or CT, there was no evidence of recurrence.

Figure 2.

Giant tumor. A: A giant tumor originating from greater omentum; B: A giant tumor originating from resected specimen.

Figure 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections. A: Collagen deposition, 10 cm × 10 cm; B: Abundant spindle cells, 10 cm × 10 cm; C: Branching vessel, 10 cm × 20 cm; D: Nuclear atypia, 10 cm × 20 cm.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical test. Immunohistochemical test showing the tumor was positive for CD34 (A), bcl-2 (B), α-smooth muscle actin (C), and vimentin (D) (10 cm × 20 cm).

DISCUSSION

SFT is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm often originating from the pleura, but occasionally from other parts of the body, including the peritoneum, mediastium, extremities, orbit, and parotid gland[1-6]. Intra-abdominal SFT is very rare; and SFT with the involvement of greater omentum is even more uncommon. We searched the PubMed and reviewed the relevant papers published till December 2011, and found only 5 SFT cases involving the omentum[11-15].

SFT is a neoplasm derived from mesenchymal cells located in the sub-mesothelial lining of the tissue space, predominantly composed of spindle-shaped cells and collagen bundles[16]. Approximately 78%-88% of SFTs are benign and 12%-22% are malignant[17,18]. The clinical and pathological properties of SFT were first reported by Klempere et al[1]. The earliest criteria for a judgment of malignancy of SFT by England et al[19] were (1) high cellularity with crowding and overlapping of nuclei; (2) high mitotic activity (more than 4 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields); and (3) pleomorphism judged as mild, moderate, or marked based on nuclear size, irregularity, and nucleolar prominence. In addition, some authors suggested a potential association of tumor size, hemorrhage and necrosis with the clinical behavior of SFT[19-21].

We summarized the clinical data of the 5 reported cases of SFT originating from omentum (Table 2). Of particular note, mitotic activity and tumor size may play a key role in predicting SFT. We suggest using risk assessment (very low risk, low risk, intermediate risk, and high risk) based on tumor size, mitotic activity, cellularity and pleomorphism to predict SFT behavior, rather than attempting to draw a sharp line between benign and malignant lesions. More frankly, malignant factors of SFT are associated with a higher risk for recurrence and metastasis. However, the small sample size limits us to draw a definite conclusion. And the detailed criteria still need to be discussed and validated by future studies.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the 5 reported cases of solitary fibrous tumor originating from omentum

| Ref. | Site | Age (yr) | Size (cm) | Weight (kg) | Immunohistochemical analysis (pos/neg) | Mitotic count | Local recurrence /metastases | Status at last follow-up |

| Salem et al[11] | Omentum | 60 | 24 × 19 × 10 | 3.87 | CD34, CD99/(SMA), desmin, CD117 | 25/10HPF | No | NED |

| 4 mo | ||||||||

| Patriti et al[12] | Greater omentum | 24 | 3.2 × 2.5 | NA | CD34, bcl-2/Pan cytokeratin reaction | 3/10HPF | No | NED |

| 2 yr | ||||||||

| Mosquera et al[13] | Omentum | 40 | 9 | NA | CD34, CD99, p16/ EMA, cytokeratin, S-100, desmin, p53 | 9/10HPF | Yes | DOD |

| 34 mo | ||||||||

| Ekıcı et al[14] | Lesser omentum | 51 | 11.5 × 8.5 × 7.5 | NA | CD 34/CD117, actin and S-100 | 0/10HPF | No | NED |

| 10 mo | ||||||||

| Gold et al[15] | Omentum | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

NA: Not available; Neg: Negative; Pos: Positive; NED: No evidence of disease; DOD: Dead of disease; HPF: High-power fields; EMA: Epithelial membrane antigen; SMA: Smooth muscle actin.

In this case, no mitotic activity and necrosis were present, and there was low cellularity, resulting in a diagnosis of a possible benign entity according to the benign-malignant system. However, the only existing risk is the giant size, and multiple prognostic factors should be taken into account in predicting SFT behavior. In our opinion, it is reasonable to judge this case to be a low-risk lesion by clinical presentation, tumor size, mitotic activity, cellularity and pleomorphism. During a 48-mo follow-up, no evidence of local recurrence or metastasis was observed.

In cases of mesenchymal tumor presenting with spindle-cell neoplasm, the differential diagnosis of SFT should be considered. It is absolutely necessary although sometimes it is difficult to clearly differentiate it from other malignant or benign entities such as hemangiopericytoma, neurofibroma, spindle cell lipoma, leiomyoma, fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, angiomyolipoma or fibroma (Table 3). Moreover, hemangiopericytoma must be included into differential diagnosis because of its vascular pattern. And electron microscopic examination can be used to exclude the presence of an external lamina, typically observed in hemangiopericytoma. Immunohisto-chemically, SFTs commonly express CD34 and bcl-2, and occasionally SMA. They are usually negative for S-100, desmin and cytokeratins[22,23]. To our knowledge, few tumors of mesenchymal origin can express both CD34 and bcl-2, which are useful to differentiate SFT from other mesenchymal tumors, because approximately 82%-95% and 88%-100% of the SFTs are positive for CD34 and bcl-2, respectively[24,25]. This report describes a giant SFT showing immunocytochemical reactivity for CD34, bcl-2, α-SMA and VIM, which is consistent with the results reported elsewhere. But what we are really concerned is how to make an exact diagnosis before operation.

Table 3.

Immunohistochemical indexes for differential diagnosis of mesenchymal tumors

| CD34 | bcl-2 | CD99 | S-100 | Cytokeratin | EMA | Calretinin | Desmin | α-SMA | |

| Solitary fibrous tumor | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | ± | ± |

| Neurofibroma | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| Spindle cell lipoma | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Synovial sarcoma | - | + | ± | - | + | + | - | - | - |

| Desmoid tumor | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| Hemangiopericytoma | + | - | ± | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | ± | ± | - | + | ± | - | - | ± | ± |

| Sarcomatoid mesothelioma | - | ± | ± | - | + | + | + | - | - |

| Schwannoma | ± | + | - | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| Calcifying fibrous pseudotumor | ± | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Smooth muscle tumor | ± | ± | ± | - | - | - | - | + | + |

α-SMA: α-smooth muscle actin; EMA: Epithelial membrane antigen.

The patients with SFT in abdominal cavity may complain of vomiting, abdominal pain or discomfort, but they are mostly asymptomatic. Tumor marker is not specific and sensitive for SFT. But in some patients with the symptom of hypoglycemia, a high expression of serum insulin-like growth factor-II (IGF-II) was reported, which was found more in the tumor cystic fluid than in serum. Consequently, after total resection of the tumor, no abnormalities were found and the hypoglycemia was resolved[26,27]. It was concluded that the tumor cells can secrete IGF-II, but the specificity and sensitivity need to be explored by further studies.

The best available diagnostic modalities are CT scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which can demonstrate a proliferation of fibrous tissues in abdominal cavity and evaluate the relationship between the tumor and the neighboring structures so as to help the surgeons make a decision whether or not to excise the tumor. Nevertheless, CT scanning and MRI can not distinguish SFT from other mesenchymal tumors. Therefore, SFT may be misdiagnosed as stromal tumor as did in our case because of their homology.

Needle aspiration biopsy for SFT provides inconclusive results because the tumor is composed of acellular and hypercellular portions and it does not provide enough tissues for cytologic analysis. Although Apple et al[28] reported that accurate diagnosis could be established by fine needle aspiration, it still needs further investigation on a larger series of patients. The rare location of SFT often gives rise to difficulties in diagnosis or to misdiagnosis before operation. However, aspiration by Ryle’s tube is a better option for large tumors and specimens could be obtained for immunohistochemical test, while for small tumors, samples can be collected through exploratory laparotomy for immunohistochemical test, thus a diagnosis can be done before operation.

Surgical treatment including local resection of this tumor is a definitive choice of treatment. Postoperative long-term follow-up is very important since SFT may recur locally. The malignant form pursues an aggressive course manifested by local invasion, recurrent growth, or metastasis[29]. Therefore, postoperative chemotherapy is recommended for malignant SFT. Moreover, half of malignant SFT cases were positive for c-kit[30] and tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as imatinib and sunitinib, which are also effective against gastrointestinal stromal tumors[31,32], have been used in the treatment of SFT[33].

In summary, we report a rare case of a giant SFT originating from greater omentum. Abdominal imaging is helpful in the diagnosis of the tumor. If CT and MRI are not useful, immunohistochemical test can be performed in preoperative diagnosis using the tumor samples collected through Ryle’s tube for small tumors and through exploratory laparotomy for large tumors. Long-term follow-up is necessary to assess the outcomes of the treatment, especially for the high-risk SFTs.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Ana Cristina Simões e Silva, MD, PhD, Full Professor of the Department of Pediatrics from the Faculty of Medicine of Federal University of Minas Gerais, Avenida Bernardo Monteiro, 1300 apt 1104, Bairro Funcionários, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil 30150-281, Brazil

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Klempere P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasmas of the pleural. Arch Pathal. 1931;11:385–412. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kubota Y, Kawai N, Tozawa K, Hayashi Y, Sasaki S, Kohri K. Solitary fibrous tumor of the peritoneum found in the prevesical space. Urol Int. 2000;65:53–56. doi: 10.1159/000064836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukushima K, Yamaguchi T, Take A, Ohara T, Hasegawa T, Mochizuki M. [A case report of so-called solitary fibrous tumor of the mediastinum] Nihon Kyobu Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;40:978–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akisue T, Matsumoto K, Kizaki T, Fujita I, Yamamoto T, Yoshiya S, Kurosaka M. Solitary fibrous tumor in the extremity: case report and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(411):236–244. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000065839.77325.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romer M, Bode B, Schuknecht B, Schmid S, Holzmann D. Solitary fibrous tumor of the orbit--two cases and a review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:81–88. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0731-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanau CA, Miettinen M. Solitary fibrous tumor: histological and immunohistochemical spectrum of benign and malignant variants presenting at different sites. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:440–449. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chetty R, Jain R, Serra S. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2009;13:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamashita S, Tochigi T, Kawamura S, Aoki H, Tateno H, Kuwahara M. Case of retroperitoneal solitary fibrous tumor. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2007;53:477–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakatani T, Tamada S, Iwai Y, Tanimoto Y. Solitary fibrous tumor in the retroperitoneum: a case with infiltrative growth. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2002;48:637–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee WA, Lee MK, Jeen YM, Kie JH, Chung JJ, Yun SH. Solitary fibrous tumor arising in gastric serosa. Pathol Int. 2004;54:436–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2004.01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salem AM, Bateson PB, Madden MM. Large solitary fibrous tumor arising from the omentum. Saudi Med J. 2008;29:617–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patriti A, Rondelli F, Gullà N, Donini A. Laparoscopic treatment of a solitary fibrous tumor of the greater omentum presenting as spontaneous haemoperitoneum. Ann Ital Chir. 2006;77:351–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosquera JM, Fletcher CD. Expanding the spectrum of malignant progression in solitary fibrous tumors: a study of 8 cases with a discrete anaplastic component--is this dedifferentiated SFT? Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1314–1321. doi: 10.1097/pas.0b013e3181a6cd33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekıcı Y, Uysal S, Güven G, Moray G. Solitary fibrous tumor of the lesser omentum: report of a rare case. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:464–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gold JS, Antonescu CR, Hajdu C, Ferrone CR, Hussain M, Lewis JJ, Brennan MF, Coit DG. Clinicopathologic correlates of solitary fibrous tumors. Cancer. 2002;94:1057–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell JD. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;15:305–309. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(03)70011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson LA. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. Cancer Control. 2006;13:264–269. doi: 10.1177/107327480601300403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Perrot M, Fischer S, Bründler MA, Sekine Y, Keshavjee S. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:285–293. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.England DM, Hochholzer L, McCarthy MJ. Localized benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura. A clinicopathologic review of 223 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:640–658. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198908000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalton WT, Zolliker AS, McCaughey WT, Jacques J, Kannerstein M. Localized primary tumors of the pleura: an analysis of 40 cases. Cancer. 1979;44:1465–1475. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197910)44:4<1465::aid-cncr2820440441>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witkin GB, Rosai J. Solitary fibrous tumor of the mediastinum. A report of 14 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:547–557. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guillou L, Fletcher JA, Fletcher CDM, Mandahl N. Extra pleural solitary fibrous tumor and hemangiopericytoma. In: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. pp. 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gengler C, Guillou L. Solitary fibrous tumour and haemangiopericytoma: evolution of a concept. Histopathology. 2006;48:63–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miettinen M, Lindenmayer AE, Chaubal A. Endothelial cell markers CD31, CD34, and BNH9 antibody to H- and Y-antigens--evaluation of their specificity and sensitivity in the diagnosis of vascular tumors and comparison with von Willebrand factor. Mod Pathol. 1994;7:82–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morimitsu Y, Nakajima M, Hisaoka M, Hashimoto H. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumor: clinicopathologic study of 17 cases and molecular analysis of the p53 pathway. APMIS. 2000;108:617–625. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2000.d01-105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filosso PL, Oliaro A, Rena O, Papalia E, Ruffini E, Mancuso M. Severe hypoglycaemia associated with a giant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2002;43:559–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hajdu M, Singer S, Maki RG, Schwartz GK, Keohan ML, Antonescu CR. IGF2 over-expression in solitary fibrous tumours is independent of anatomical location and is related to loss of imprinting. J Pathol. 2010;221:300–307. doi: 10.1002/path.2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Apple SK, Nieberg RK, Hirschowitz SL. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. A report of two cases with a discussion of diagnostic pitfalls. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:1528–1533. doi: 10.1159/000332871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramdial PK, Nadvi S. An unusual cause of proptosis: orbital solitary fibrous tumor: case report. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:1040–1043. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199605000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butnor KJ, Burchette JL, Sporn TA, Hammar SP, Roggli VL. The spectrum of Kit (CD117) immunoreactivity in lung and pleural tumors: a study of 96 cases using a single-source antibody with a review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:538–543. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-538-TSOKCI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dagher R, Cohen M, Williams G, Rothmann M, Gobburu J, Robbie G, Rahman A, Chen G, Staten A, Griebel D, et al. Approval summary: imatinib mesylate in the treatment of metastatic and/or unresectable malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3034–3038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen P, Zong L, Zhao W, Shi L. Efficacy evaluation of imatinib treatment in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4227–4232. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i33.4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stacchiotti S, Negri T, Palassini E, Conca E, Gronchi A, Morosi C, Messina A, Pastorino U, Pierotti MA, Casali PG, et al. Sunitinib malate and figitumumab in solitary fibrous tumor: patterns and molecular bases of tumor response. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1286–1297. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]