Abstract

It is evident that epigenetic factors, especially DNA methylation, play essential roles in obesity development. Using pig as a model, here we investigated the systematic association between DNA methylation and obesity. We sampled eight variant adipose and two distinct skeletal muscle tissues from three pig breeds living within comparable environments but displaying distinct fat level. We generated 1,381 gigabases (Gb) of sequence data from 180 methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) libraries, and provided a genome-wide DNA methylation map as well as a gene expression map for adipose and muscle studies. The analysis showed global similarity and difference among breeds, sexes and anatomic locations, and identified the differentially methylated regions (DMRs). The DMRs in promoters are highly associated with obesity development via expression repression of both known obesity-related genes and novel genes. This comprehensive map provides a solid basis for exploring epigenetic mechanisms of adipose deposition and muscle growth.

Introduction

Obesity can be considered an epidemic that has become a major threat to the quality of human life in modern society1. By 2030, up to 58% of the world’s adult population might be either overweight or obese1. Adipose tissues (ATs) and skeletal muscle tissues (SMTs) play important role in the pathogenesis of obesity and its comorbidities by secreting cytokines involved in the regulation of metabolism2,3.The metabolic risk factors of obesity and increased body weight are more related to adipose distribution rather than the total adipose mass4,5. ATs located within the abdominal and thoracic cavity, known as visceral adipose tissues (VATs), have been recognized to be anatomically, functionally and metabolically distinct from that of the compartmental subcutaneous adipose tissues (SATs)6, and have been found to be related to a series of diseases including cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome7. Nonetheless, SATs can have direct and beneficial effects on control of body weight and metabolism8.

Pig (Sus scrofa) is emerging as an attractive biomedical model for studying energy metabolism and obesity in humans because of their similar metabolic features, cardiovascular systems, proportional organ sizes, and lack of brown adipose postnatally9. The pig model offers, in fact, the advantages of low genetic variance, homogeneous feeding regime, and remitting confounding factors typical of humans, such as smoking, alcohol drinking, etc. In the modern industry, pigs have undergone strong genetic selection in the relatively inbred commercial lines for lean meat production or in some cases for adipose production, which has led to remarkable phenotypic changes and genetic adaptation, making these breed lines a perfect model for comparative studies10,11.

There has been extensive research to hunt for “obesity alleles”, most recently by whole-genome association studies12,13. It is evident that DNA sequence polymorphism alone does not provide adequate explanations for mechanisms of obesity regulation. Recently, epigenetic factors, especially DNA methylation that is a stably inherited modification affecting gene regulation and cellular differentiation, has gained a greater appreciation as an alternative perspective on the aetiology of complex diseases14,15. Nevertheless, current understanding of the roles of DNA methylation in the aetiology of obesity remains fairly rudimentary16.

Here, for three well defined pig breeds displaying distinct fat contents in comparable environments, we collected eight ATs from different body sites and two phenotypically distinct SMTs, and studied genome-wide DNA methylation differences among breeds, sexes, and anatomic locations. We showed the landscape of methylome distribution in the genome, analyzed differentially methylated regions (DMRs), and identified genes that were involved in the development of obesity. The work performed here will serve as a valuable resource for future functional validation and aid in searching for epigenetic biomarkers for obesity prediction and prevention, and promoting further development of pig as a model organism for human obesity research.

Results

Samples and their obesity-related phenotypes

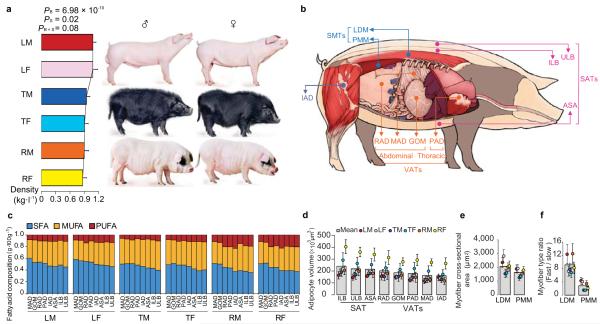

We chose three pig breeds in this study, based on known history of breed formation and measurement of obesity-related phenotypes (see Supplementary Methods). The Landrace breed has been selected for less adipose for more than 100 years in Europe, whereas the Rongchang breed was selected for extreme adipose. The Tibetan breed is almost a feral breed that has undergone very little artificial selection. On average, adult females exhibit higher fat percent than males upon reaching sexual maturity at 210-days old. To investigate sexual differences, we also separated males and females in the comparison. As expected, body density, which negatively correlates with fat percent, showed significant difference among the three breeds (two-way ANOVA, PB = 6.98 × 10−10) and between male and female (two-way ANOVA, PS = 0.02) (Fig. 1a). Measurement of metabolism indicators in serum also revealed the same ranking (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 1. Characteristics of pig adipose tissues (ATs) and skeletal muscle tissues (SMTs).

(a) Body density difference among Landrace (L), Tibetan (T) and Rongchang (R) pigs, and between male (M) and female (F). Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (n = 9 per breed per sex). ‘B’ and ‘S’ mean breed and sex, respectively. Values are means ± s.d.

(b) Sources of tissues: three subcutaneous ATs (SATs) (ASA: abdominal subcutaneous adipose, ILB: inner layer of backfat, ULB: upper layer of backfat), four visceral ATs (VATs) (GOM: greater omentum, MAD: mesenteric adipose, RAD: retroperitoneal adipose, PAD: pericardial adipose), intermuscular adipose (IAD) and two SMTs (LDM: longissimus dorsi muscle, and PMM: psoas major muscle).

(c) Fatty acid composition difference. SFA, MUFA and PUFA mean saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acid, respectively. Three-way repeated-measures ANOVA (n = 9 per breed per sex per tissue). (SFA: PB = 2.46 × 10−7, PS = 1.35 × 10−6, PT = 0.99, PB×S = 0.19, PB×T = 0.96, PS×T = 0.69, PB×S×T = 0.77; MUFA: PB = 0.006, PS = 0.0004, PT = 0.98, PB×S = 0.99, PB×T = 0.99, PS×T = 0.93, PB×S×T = 0.77; and PUFA: PB = 0.0008, PS = 0.14, PT = 0.98, PB×S = 0.03, PB×T = 0.99, PS×T = 0.56, PB×S×T = 0.099).

(d) Adipocyte volume difference. Three-way repeated-measures ANOVA (n = 9 per breed per sex per tissue). ‘T’ means tissue. (PB < 10−16, PS = 10−16, PT = 6.74 × 10−12, PB×S < 10−16, PB×T = 0.29, PS×T = 0.36, PB×S×T = 0.99). Values are means ± s.d.

(e) Myofiber cross-sectional area difference. Three-way repeated-measures ANOVA (n = 9 per breed per sex per tissue). (PB < 10−16, PS = 0.005, PT = 9.66 × 10−12, PB×S = 0.44, PB×T = 0.01, PS×T = 0.583, PB×S×T = 0.07).

(f) Myofiber type ratio difference. Three-way repeated-measures ANOVA (n = 9 per breed per sex per tissue). (PB = 4.42 × 10−10, PS = 5.45 × 10−9, PT < 10−16, PB×S = 0.004, PB×T = 0.02, PS×T = 1.61×10−5 , PB×S×T = 0.04).

To study adipocyte regulation in different anatomic locations, we sampled eight ATs from various body regions (Fig. 1b), which exhibited dissimilar fatty acid composition (Fig. 1c) and significantly different adipocyte volumes (three-way ANOVA, PT = 6.74 × 10 −12) among the three breeds (three-way ANOVA, PB < 10−16) and between males and females (three-way ANOVA, PS = 10−16) (Fig. 1d; Supplementary Fig. S2). We also sampled two SMTs, white LDM and red PMM (Fig. 1b), representing two different fiber types, of which PMM has a higher percentage of capillaries, myoglobin, lipids and mitochondria17. Compared with PMM, LDM has higher myofiber cross-sectional area (three-way ANOVA, PT = 9.66 × 10−12) (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Fig. S2) and ratio of fast to slow twitch myofiber (three-way ANOVA, PT < 10−16) (Fig. 1f; Supplementary Fig. S2). There is also significant divergence in myofiber cross-sectional area (three-way ANOVA, PB < 10−16, PS = 0.005) and myofiber type ratio (three-way ANOVA, PB = 4.42 × 10−10, PS = 5.45 × 10−9) among the three breeds and between the two sexes. These phenotypic differences for ATs and SMTs between breeds, sexes and anatomic locations imply the intrinsically epigenomic differences.

Landscape of the DNA methylomes

We generated a total of 1,381 gigabases (Gb) methylated DNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeDIP-seq) data from 180 samples (~7.67 Gb per sample), of which 1,067 Gb (77.3%) clean reads were aligned on the pig genome. After removing the ambiguously mapped reads and reads which may have come from duplicate clones, we used 993 Gb (71.9%) uniquely aligned non-duplicate reads in the following analysis (Supplementary Table S1). To avoid false positives in enrichment, we required at least 10 reads to determine a methylated CpG in a sample. On average, 16.1% of the CpGs were covered by this threshold (Supplementary Fig. S3).

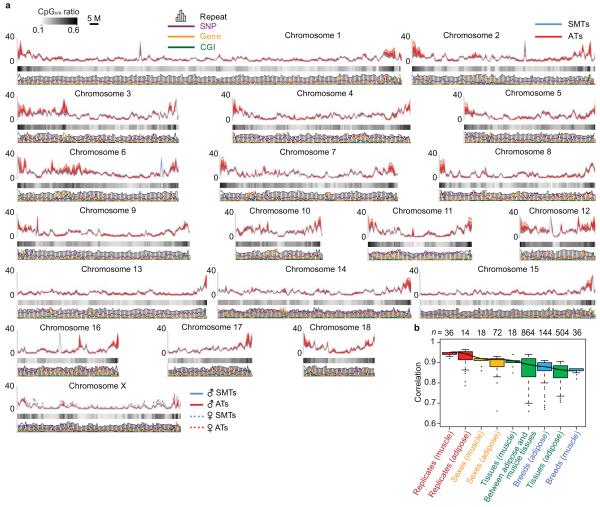

Measurement of DNA methylation level along chromosomes showed that the X chromosome is globally hypermethylated in females compared to males (Fig. 2a), which can be explained by X chromosome inactivation in females18. Through comparison of DNA methylation level between each pair of samples, we found variable correlation rates in different categories (Fig. 2b). The biological replicates highly correlated with each other (median Pearson r = 0.95 for SMTs, and 0.94 for ATs), which suggested both experimental reliability and epigenetic consistency within the same breed/sex/tissue type group. The correlation rates were relatively lower between male and female (median Pearson r = 0.92 for SMTs and 0.91 for ATs), and even lower between different anatomic locations (median Pearson r = 0.91 for SMTs, 0.89 for between ATs and SMTs, and 0.87 for ATs) and between different breeds (median Pearson r = 0.88 for ATs, and 0.84 for SMTs), indicating significant biological differences in the latter categories.

Figure 2. Chromosomal profiles of pig ATs and SMTs methylomes and their variability.

(a) Distribution of DNA methylation level on the pig genome. To compare DNA methylation rates among samples, read depth was normalized by overall average amount of reads in each group, and then a 1 Mb sliding window was used to smooth the distribution. The CpGo/e ratio, density of SNP, gene, repeat and CGI were all calculated by 1Mb sliding window.

(b) Boxplots of pairwise Pearson correlation on methylation rate between samples. The correlation rate between every two samples was calculated by 1kb sliding window. Then these correlation rates were grouped into the following categories: biological replicates, the same sex, the same tissues, the same breeds, and between adipose and muscle tissues. Since X chromosome has obviously higher methylation level in female than in male, we excluded it in the analysis between sexes. Boxes denote the interquartile range (IQR) between the first and third quartiles (25th and 75th percentiles, respectively) and the line inside denotes the median. Whiskers denote the lowest and highest values within 1.5 times IQR from the first and third quartiles, respectively. Outliers beyond the whiskers shown as black dots.

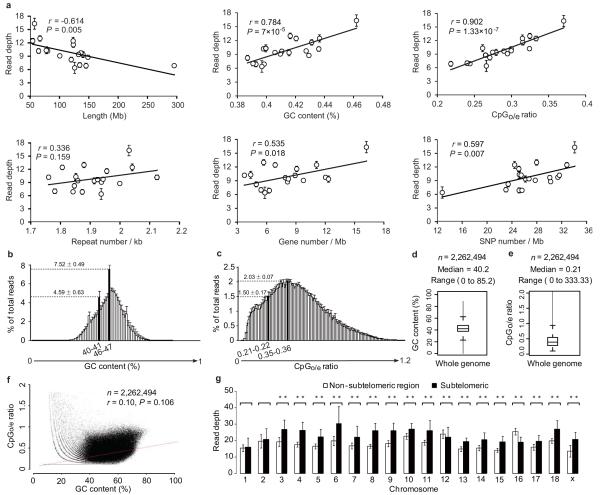

We observed that methylation level correlates negatively with chromosome length (Pearson r = −0.614, P = 0.005) and positively with GC content (Pearson r = 0.784, P = 7 × 10−5), repeat density (Pearson r = 0.336, P = 0.159), gene density (Pearson r = 0.535, P = 0.018), and especially with observed over expected number of CpG (CpGo/e) ratio (Pearson r = 0.902, P = 1.33 × 10−7) (Fig. 3a), which is consistent with previous reports19. More detailed analysis showed that the regions with GC content around 46% and CpGo/e ratio around 0.35 tend to have a higher methylation level (Fig. 3b, c), where the average GC content in the pig genome is 40% and CpGo/e ratio is 0.21 (Fig. 3d, e). Nonetheless, there is no significant correlation between GC content and CpGo/e ratio on a genomic scale (Pearson r = 0.10, P = 0.106) (Fig. 3f). The analysis showed that CpGo/e ratio has a higher correlation rate with DNA methylation level than with GC content. SNP density also positively correlated with methylation level (Pearson r = 0.597, P = 0.007) (Fig. 3a). Although substantial association of SNP density and DNA methylation level has been found20, the mechanism is still unclear. Furthermore, the gene-rich subtelomeric region (7 Mb from each telomere) has significantly higher methylation in most (~80%, 15 out of 19) chromosomes (Student’s t-test, P <0.01) (Fig. 3g).

Figure 3. DNA methylation level with genomic features.

(a) The Pearson’s correlation between DNA methylation level and features of pig autosomes (chromosomes 1-18) and sex chromosome X. The read depth was plotted against the length, GC content, repeat density, gene density, CpGo/e ratio, and SNP density of individual chromosome. Line represents linear regression. Values are means ± s.d (n = 180).

(b-e) Sequencing reads distribution against CpGo/e ratio and GC content. Reads distribution against (b) GC content and (c) CpGo/e ratio over all samples. Values are means ± s.d (n = 180). Box plot of (d) GC content and (e) CpGo/e ratio of the whole genome in 1 kb windows. Boxes denote the interquartile range (IQR) between the first and third quartiles (25th and 75th percentiles, respectively) and the line inside denotes the median. Whiskers denote the lowest and highest values within 1.5 times IQR from the first and third quartiles, respectively. Outliers beyond the whiskers shown as black dots. The 46-47% GC content and 0.35-0.36 CpGo/e ratio are corresponding to the maximal % of total reads, i.e. 7.52 ± 0.49% and 2.03 ± 0.07%, respectively. The genomic median of GC content (40-41%) and CpGo/e ratio (0.21-0.22) are corresponding to 4.59 ± 0.63% and 1.50 ± 0.17% of total reads, respectively.

(f) GC content vs. CpGo/e ratio plot of 1 kb windows across the pig genome. The pig genome was divided into 2,262,494 windows of 1 kb, and the windows were used to calculate the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) between the GC content and CpGo/e ratio. Red line represents linear regression.

(g) Methylation levels in subtelomeric (up to 7 Mb from each telomere) and non-subtelomeric regions in each chromosome. (Student’s t-test, **P <0.01). Values are means ± s.d (n = 180).

Characterization of differentially methylated regions (DMRs)

We used statistics to measure the methylation rate changes, and defined DMRs across breeds (B-DMRs), sexes (S-DMRs) and tissues (T-DMRs) (see Supplementary Methods). The high correlattion (average Pearson r = 0.994) between the number of DMRs, the number of CpGs in DMRs, and the length of DMRs implied that DMR detection in regions of different length and its embeded number of CpGs was non-biased. The number of DMRs varied considerably between categories (e.g. 387 muscle S-DMRs versus 218,623 muscle B-DMRs) (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of differentially methylated regions (DMRs).

| DMRs type | Number of DMRs |

Percentage of genomic length* |

Percentage of genomic CpG number† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle S-DMRs (n = 18 per sex) | 387 | 0.004 | 0.012 |

| Adipose S-DMRs (n = 72 per sex) | 1,831 | 0.021 | 0.061 |

| Muscle T-DMRs (n = 18 per tissue) | 2,510 | 0.032 | 0.092 |

| Adipose (n = 144) vs muscle (n = 36) T-DMRs | 82,100 | 1.49 | 3.63 |

| Adipose B-DMRs (n = 48 per breed) | 100,986 | 1.69 | 4.32 |

| Adipose T-DMRs (n = 18 per tissue) | 191,567 | 4.34 | 11.52 |

| Muscle B-DMRs (n = 12 per breed) | 218,623 | 4.89 | 12.98 |

The length of total DMRs compared with the length (~2.26 billion bp) of pig genome (Sscrofa9.2).

The number of CpGs in total DMRs compared with the number of CpGs (~26.91 M) in pig genome (Sscrofa9.2).

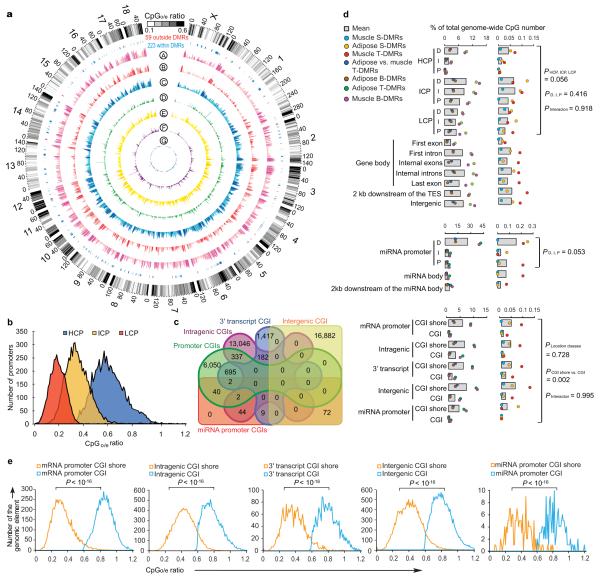

A macroscopical display of DMRs along chromosomes shows that DMR-rich regions also predominantly have higher CpGo/e ratios (~0.35) than the genomic average (0.21) (Fig. 4a). Over 20% of DMRs are located in subtelomeric regions, which only occupy 11.76% of the whole genome. Among the 282 pig genes that were orthologs to known human obesity-related genes2,12,13,21, 223 (~80%) were within our defined DMRs (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Data 1 and 2), which suggested that the DMRs have high association with the known obesity-related genes and these genes may play functional roles in obesity development by ways of methylation rate changes.

Figure 4. Genome-wide distribution of differentially methylated regions (DMRs).

(a) Circular representation of the genome-wide distribution of DMRs. This visualization was generated using the Circos software58. The outermost circle displays pig chromosomes with scale and the CpGo/e ratio at 1 Mb bins. The second circle displays the 282 pig genes that are orthologs to the well-annotated human obesity-related genes (Supplementary Data 1), of which 223 (79%) genes overlapping the defined DMRs are in blue color and the remaining 59 genes (21%) in red (Supplementary Data 2). The third to ninth circles represent seven categories of DMRs (A: Muscle B-DMRs, B: Adipose T-DMRs, C: Adipose B-DMRs, D: Adipose vs. muscle T-DMRs, E: Muscle T-DMRs, F: Adipose S-DMRs, and G: Muscle S-DMRs). The height of the histogram bins indicates number of CpGs in the DMRs. The DMR-rich (deep color, χ2 test, P < 0.001) and DMR-poor (light color, χ2 test, P > 0.001) bins are defined by comparing with genome average. TES: transcription end site.

(b) All 17,930 promoters in the pig genome were classified into three types based on CpG representation. High CpG promoters (HCPs, blue, n = 7,249), intermediate CpG promoters (ICPs, yellow, n = 6,629), and low CpG promoters (LCPs, red, n = 4,052).

(c) Venn diagram showing the distribution of all 38,778 CGIs in the pig genome among five CGI classes. Promoter CGIs (n = 7,126), intragenic CGIs (n = 13,611), 3′ transcript CGIs (n = 2,305), intergenic CGIs (n = 16,954) and miRNA promoter CGIs (n = 169) were defined according to their genomic locations. There are overlaps between five classes of CGIs, due to the overlapping gene annotation at a specific genome coordinate.

(d) Percentage of CpGs within DMRs in each of the 31 genomic elements. The statistical significance of comparison among the three miRNA promoters (D, I, P) was calculated by one-way repeated-measures ANOVA, while others by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA.

(e) Distribution of CpGo/e ratio for CGIs and their shores in five CGI classes. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to determine the difference of CpGo/e ratio between CGIs and their shores.

We then looked at DMRs in the 31 categories of functional genomic elements. We separated promoters into three types according to CpG representation as previously described22 (Fig. 4b), and also classified CpG islands (CGIs) into five classes according to their genomic locations as previously described23 (see Methods) (Fig. 4c). DMRs occur more frequently in intermediate CpG promoter (ICP) than in high CpG promoter (HCP) and low CpG promoter (LCP) regions (two-way ANOVA, P = 0.056) (Fig. 4d). The ICP class contains many weak CGIs24 (<500 bp, have moderate CpG richness and/or have a GC content below 55%). This result validated previous findings that weak CGIs are more predisposed to regulation by DNA methylation and preferential targeting of weak CGIs is a general phenomenon in mammals22. Promoter hypermethylation plays a critical role in suppressing gene expression, yet in gene bodies it is also important in regulating alternative promoters and preventing spurious transcription initiation23. Interestingly, the first exon regions have the lowest DMRs within the gene body (Fig. 4d), which may be due to some functional motifs overlapping between the proximal region of promoters and first exons. In addition, the distal (D) regions of both mRNA and microRNA (miRNA) promoters have more DMRs than the intermediate (I) and proximal (P) regions (Fig. 4d), suggesting that changes in methylation at D regions of promoters may be a more prevalent mechanism for producing transcriptional variability. We found that most DMRs are located in CGI shores rather than in CGIs (Fig. 4d) in all five classes of genomic elements (two-way ANOVA, P = 0.002), which is consistent with previous reports25-27. CpGo/e ratio of most CGI shores is around 0.35-0.36, while CGIs have CpGo/e ratios far greater than this cutoff (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P < 10−16) (Fig. 4e), as shown by the plot of reads distribution against CpGo/e ratio in Fig. 3c.

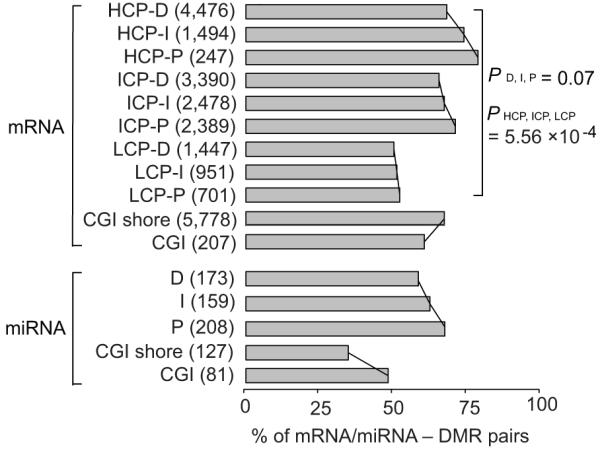

Promoter methylation and transcriptional repression

We explored the correlation between methylation rate in promoters and expression level of associated mRNAs and miRNAs (Fig. 5; Supplementary Fig. S4). It is believed that DNA methylation in promoters is only one of the several mechanisms for regulating gene expression; hence it’s logical that not all genes have correlated methylation and expression patterns. The order of correlation level in mRNA promoters, from high to low, was HCP, ICP, LCP, and P, I, D (Fig. 5), which validated previous report28. Nonetheless, since DMRs are enriched in ICPs and D regions of promoters (Fig. 4d), there were more mRNA-DMR pairs exhibiting correlation in ICP (8,257) than in HCP (6,217) and LCP (3,099), and more pairs in D region (9,313) than in I (4,923) and P (3,337) regions (Fig. 5). Further, it indicated that the CpG content difference of promoters has a more profound impact on mRNA expression (two-way ANOVA, P = 5.56 × 10−4) than the distance to transcription start site (TSS) of the regions in promoters (two-way ANOVA, P = 0.07).

Figure 5. Percentage of mRNAs and miRNAs having expression level negatively correlated with promoter methylation level.

Only 3,074 probes uniquely representing 3,074 mRNA and 611 uniquely mapped miRNA genes with the high-confidence expression data from the same samples for MeDIP-seq were used (see Supplementary Methods). The mRNA/miRNA – DMR pairs which have down-regulation together with promoter hypermethylation, or up-regulation together with promoter hypomethylation, were taken as having negative correlation between expression and methylation. The total number of identified mRNA/miRNA – DMR pairs was shown in the brackets. Grey bars represent the percentage of mRNA/miRNA– DMR pairs that exhibit the inverse relationship in total mRNA/miRNA – DMR pairs. The statistical significance was calculated by two-way non-repeated-measures ANOVA.

There was correlation between miRNA expression and methylation rate in P regions of miRNA promoters (Pearson r = −0.368, P = 4.44 × 10−8), but almost no correlation in I (Pearson r = −0.116, P = 0.146) and D (Pearson r = 0, P = 0.996) regions of miRNA promoters (Supplementary Fig. S4). Primary miRNA transcripts (pri-miRNAs) can be several thousand bases long and embeds a ~70 nt long stem-loop precursor (pre-miRNA)29. Although little is known about the TSS of pri-miRNA30, the results here suggested that DNA methylation in 5′ upstream of pre-miRNAs could play a role in transcriptional silencing of mature miRNA.

Methylation in CGI shores had stronger (Pearson r = −0.146, P = 6.15 × 10−29) correlation with mRNA expression than in CGIs (Pearson r = −0.128. P = 0.066) (Supplementary Fig. S4), which is consistent with the previous studies25-27. Nonetheless, miRNA expression has little or no correlation with CGI (Pearson r = −0.133, P = 0.241) and CGI shore methylation (Pearson r = 0.099, P = 0.268). A recent study also showed that a common feature of DNA methylation-repressed miRNAs is the absence of CGIs in the promoter region31.

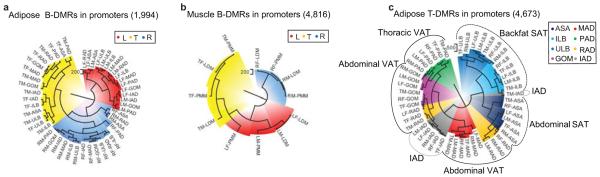

Promoter DMRs best discriminate breeds and tissues

To analyze whether DMRs exhibit any breed, sex and/or anatomic locations specific pattern, we performed unsupervised clustering for all samples using DMRs of each category of genomic elements. The adipose and muscle B-DMRs in promoters were well clustered by breed (Fig. 6a, b). Clustering of samples by corresponding mRNA expression is generally similar (Supplementary Fig. S5), indicating consistent relationships between DNA methylation in promoters and gene expression. The clustering by B-DMRs in CGI shores can group most samples from each breed, but not as distinctly as that by B-DMRs in promoters. This suggested that, although methylation in CGI shores is important in regulating gene expression25-27, methylation differences at promoters are better predictors of differences among the breeds. The clustering by B-DMRs of other genomic elements is even less distinct, suggesting that most methylation in these genomic elements may have weak or no direct association with functional divergence of the three breeds.

Figure 6. Hierarchical clustering of samples using DMRs in promoters.

(a) Clustering of adipose samples using 1,994 adipose B-DMRs in promoters.

(b) Clustering of muscle samples using 4,816 muscle B-DMRs in promoters. By definition, the three pig breeds are completely segregated. The three major subgroups in the radial dendrograms correspond perfectly to pig breed regardless of sexes and tissue types.

(c) Clustering of adipose samples using 4,673 adipose T-DMRs in promoters results in most of the eight variant adipose samples are discriminated from each other. The numbers in the brackets showed the amount of DMRs used in clustering.

The B-DMRs in promoters of adipose tissues showed that the Rongchang and Tibetan breed are closer to each other than the Landrace pig (Fig. 6a). The same analysis in muscle tissues showed that the Landrace breed is closer to the Tibetan than the Rongchang breed (Fig. 6b). The same distance relationship pattern of the three breeds is reflected by the corresponding mRNA expression data clustering (Supplementary Fig. S5). The different clustering patterns may be explained by the marked phenotypic changes between the feral Tibetan, the leaner Landrace and the fatty Rongchang pig breeds due to opposite breeding direction, which results in differences not only at the genetic level, but also in the epigenetic state, and potential genotype-epigenotype interactions32 as well.

In addition, the T-DMRs in promoters could largely cluster samples of the same tissue type together (Fig. 6c), indicating that promoter methylation also correlates with adipose distribution across the anatomic locations. It is well established that VATs have intrinsic features distinct from SATs, and are more highly correlated with the metabolic risk factors of obesity than SATs4,6-8. Interestingly, IAD that deposited between muscle bundles, was more similar to VATs in terms of methylation. This observation suggests that IAD may be a new risk factor for obesity related diseases. PAD around coronary arteries is a higher correlative risk factor for cardiovascular disease than other VATs, and although thoracic PAD shares a common embryonic origin with other abdominal VATs—the splanchnic mesoderm33, we observed significant site specific differences in methylation rate between them (Fig. 6c). Tissue types are also better discriminated by T-DMRs in promoters than in other genomic elements (Supplementary Fig. S5). X chromosome methylation between male and female is expected to be significant due to the overriding effect of X chromosome inactivation in females18. Clustering of S-DMRs by sex was less distinct after removing DMRs on the X chromosome (Supplementary Fig. S5).

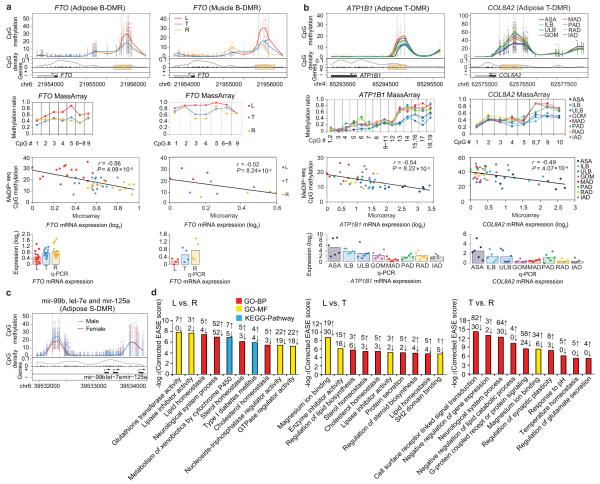

Genes involved in phenotypic divergence

To study the association of differential methylation in promoter regions with phenotypic divergence, we first investigated the relationship between DNA methylation at promoters and the expression data of known obesity-related genes obtained through and MassArray and quantitative PCR (q-PCR). For example, FTO (fat mass- and obesity-associated gene) is a gene unequivocally associated with obesity and is ubiquitously expressed34,35. From the leaner Landrace, feral Tibetan to the fatty Rongchang breed and across both adipose and muscle tissue types, FTO is hypermethylated in the D region of the promoter with a lower gene expression level (Fig. 7a). The fact that the level of methylation is highest in Landrace pig and lowest in Rongchang pig is consistent with the observation that loss of FTO expression and/or function protects against obesity and food intake35. ATP1B1, which encodes the ubiquitously expressed β subunit of Na+/K+ ATPase, is required for the proper cellular positioning of ATPase and its stability. Decreased ATPase activity precedes obesity and hyperinsulinemia by influencing thermogenesis and energy balance36. COL8A2, which encodes the α2 chain of type VIII collagen, is necessary for mesangial matrix expansion as well as for hypercellularity. Lack of COL8A2 confers renoprotection in diabetic nephropathy37. Both ATP1B1 and COL8A2 have hypermethylation in I region of promoter and lower gene expression level that is more pronounced in the VATs and IAD than SATs (Fig. 7b), suggesting that hypermethylation in promoters of these two genes are potential biomarkers of high-risk visceral obesity.

Figure 7. Examples of obesity-related genes and functional gene categories showing differential DNA methylation in promoters.

(a) The adipose and muscle B-DMR in FTO promoter. Top panels: top half: CpG methylation. Each point represents methylation level (MeDIP-seq read depth) of a sample at a given CpG site. The curves showed average over the samples. The two vertical dashed lines marked the boundaries of the DMR identified. Lower half: CpG dinucleotides (black tick marks on X axis), CpG density (gray line), TSS (black arrow), exons and introns (filled black and white boxes, respectively). Plus and minus marks denote sense and antisense gene transcription. Second panels: validation of individual CpG methylation by MassArray (mapping to yellow box in upper panel). Third panels: a scatter plot and trend line (Pearson correlation) showing correlation between the log2 ratios of mRNA expression from microarray and CpG methylation of the DMR from MeDIP-seq. Bottom panels: validation of mRNA expression levels by q-PCR. Bars represent the mean expression level.

(b) The adipose T-DMR in ATP1B1 and COL8A2 promoters.

(c) The adipose S-DMR in miRNAs mir-99b, let-7e and mir-125a promoters.

(d) Top ten GO (Gene Ontology) and pathway categories enriched for adipose B-DMRs in promoters. The enrichment analysis was performed using the DAVID software59 (see Supplementary Methods). The EASE score, indicating significance of the comparison, was calculated using Benjamini corrected modified Fisher’s exact test. BP: biological process, MF: molecular function.

We also found correlation between methylation in promoter and gene expression, and reasonable association to breed and anatomic location divergence, for many other genes with known roles in adipose deposition and muscle growth. For example, ESD that increases expression in obesity prone models38; PPP1R3C that functions against intramyocellular lipid buildup and reduces circulating leptin and triglycerides39; GHSR that promotes GH-release and increased lean but not fat mass in obese subjects40; LIPA that inhibits intramuscular lipid stores41; MC4R that inhibits food intake and prevents hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycinemia42; and PROX1 that prevents lymphatic vascular defects that cause adult-onset obesity43 (Supplementary Fig. S6). The genes preferentially expressed in adipose (such as HEXB and HTR2A) or muscle (such as ACE, PRKAR1A and PRKCQ) tissues only, were validated by the methylation in promoter and gene expression data as well (Supplementary Fig. S6). The full list of candidate obesity-related genes we collected together with their DNA methylation pattern in promoters is provided in Supplementary Data 1 and 2.

In addition, out of the 2,311 genes/~282.57 Mb quantitative trait loci (QTLs) region assembled from 901 high confidence and narrowed (< 2Mb) QTLs affecting fatness and pork quality in the PigQTL database44, 1,669 (72.22%) genes overlap with the defined DMRs (Supplementary Data 3-5). This high consistency highlights the potential of identifying candidate regions or genes of quantitative traits (such as obesity) based on genome-wide DNA methylation data, such as the newly developed methylation QTL (methQTL) analysis15. Notably, out of 77 putative genes located in these QTLs region, 66 (85.71%) overlap with our defined DMRs. Methylation level of these gene’s promoters strongly inversely correlated with the gene expression, suggesting that these uncharacterized protein coding genes may be involved in adipose deposition and muscle growth. Typical examples are shown in Supplementary Fig. S7.

Furthermore, numerous miRNAs having known or potential roles in obesity were also identified (Supplementary Data 6). We found a S-DMR with hypermethylation in males compared to females. This S-DMR is located in the promoter region of a miRNA cluster that includes adjacent miR-99b, let-7e and miR-125a (Fig. 7c). Although no previous evidence exists for a direct relationship of these three miRNAs to obesity, the key functions and targets of these miRNAs are associated with the suppression of prostate cancer in male45 and breast cancer in female46, and therefore potentially contribute to sexual differences in obesity development.

To identify novel genes potentially responsible for phenotypic differences, we performed enrichment analysis for genes with DMRs in promoters (Supplementary Fig. S8; Supplementary Data 7 and 8). As expected, most enriched functional GO categories of adipose B-DMRs in promoters were related to the pathogenesis of obesity, such as ‘homeostasis of sterol, lipid, cholesterol’, ‘lipase inhibitor activity’, ‘type I diabetes mellitus’, and ‘dyslipidemia’ (Fig. 7d). Notably, the multigene family of glutathione transferase and cytochrome P450, two important groups of multifunctional detoxifying enzymes responsible for metabolizing an array of xenobiotic compounds47,48, were among the enriched adipose B-DMRs in promoters (Fig. 7d). ‘Trans-1,2-dihydrobenzene-1,2-diol dehydrogenase activity’ enzymes, which also participate in metabolism of endocrinally disruptive xenobiotics49, were universally identified among enriched adipose T-DMRs in promoters (Supplementary Data 8). Pigs as well as humans are exposed to an increasing numbers of environmental xenobiotics through ingestion of contaminated food or water, inhalation of polluted air or even dermal exposure. A link between exposure to endocrinally disruptive xenobiotics and obesity has been proposed50. Our finding suggests that DNA methylation rate changes of genes coding for detoxifying enzymes induced by pollutants may potentially explain the pathogenicity of obesity caused by chemical environmental endocrine disruptors.

Our analyses also revealed many other functional gene categories that were potentially involved in adipose and muscle regulation (Supplementary Data 8). For example, immune-related gene categories, including ‘RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway’, ‘interferon-α/β receptor binding’, ‘natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity’, and ‘antigen processing and presentation’, were identified among the enriched muscle B-DMRs in promoters, which is consistent with previous finding of obesity-induced immune dysfunction51. Intriguingly, given that adipose tissue derives from mesoderm, the identification of ‘mesoderm development’ gene category among enriched adipose S-DMRs in promoters indicated that sex-specific obesity is potentially related to the establishment of differential methylation during embryonic development. In addition, the enriched gene categories of muscle T-DMRs, and adipose vs. muscle T-DMRs in promoters reflected the well characterized tissue-specific functions. Methylation differences in genes coding for proteins involved in GTP-related energy metabolism may be responsible for the differences in percentage of mitochondria between the two phenotypically distinct SMTs17. Differential methylation of genes involved in ‘cytoskeletal protein binding’, ‘regulation of cellular protein metabolic process’ and ‘enzyme activator activity’ may explain the developmental differences between adipose and muscle tissues52.

Discussion

This study reports the comprehensive genome-wide epigenetic survey of various adipose and skeletal muscle tissues based on directly sequenced animal DNA methylomes. Through identification of DMRs among breeds, sexes and anatomic locations, and classification of the DMRs according to their locations in various genomic elements, we found that DMRs in promoters can repress gene expression and are highly associated with phenotypic variation. Identified DMRs were preferentially situated in ICP (intermediate CpG promoters) and in CGI shores. This validated the hypothesis that weak CGIs are more prone to regulation by DNA methylation since the higher feasibility for weak CGIs to become de novo methylated regions, and preferentially associated with general phenomenon and non-malignant, common complex diseases (such as obesity) instead of the highly heterogeneous lesions (such as cancer)22. We also found that the intermuscular IAD was more similar to the VATs in methylation pattern, which provided the first epigenomic evidence for IAD as a candidate risk factor for obesity. The dataset and research here shed new light on the epigenomic regulation of adipose deposition and muscle growth.

It is considered that pigs can serve as a good biomedical model for human obesity studies because they share the same general physiology with human. Indeed, we found that about 80% of the known or candidate human obesity-related genes and 72% of genes in QTLs region that affect fatness and pork quality were within our defined DMRs. Detailed analysis indicated that the methylation regulation patterns of these genes are consistent with their known biological functions. We also predicted many novel candidate genes that were associated with variation in obesity-related phenotypes and that require further experimental validation. Domesticated breeds also provide additional advantage of highly homogeneous genetic backgrounds, large litter size (10~12 piglets per litter; 24~36 piglets per year), short generation interval (12 months) and a homogeneous feeding regime, which are particularly suitable for survey of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance53. In addition to providing new information for biomedical research, genomic/epigenomic studies of pigs may also help uncover the molecular basis that underlies economic traits in pig, which can be used to improve the efficiency of artificial selection, hence the production of healthier pork.

Methods

Animals

Nine females and nine males at 210-days-old for each of the Landrace (a leaner, Western breed), the Tibetan (a feral, indigenous Chinese pig that has not undergone artificial selection) and the Rongchang (a fatty, Chinese breed) pig breeds were used in this study. There is no direct and collateral blood relationship within the last three generations among the 18 pigs from each of the breeds. The piglets were weaned simultaneously at 28 ± 1 day of age. A starter diet provided 3.40 Mcal·kg−1 metabolizable energy (ME), 20.00% crude protein and 1.15% lysine from the 30th to 60th days after weaning. From the 61st to 120th days, the diet contained 3.40 Mcal·kg−1 ME, 17.90% crude protein and 0.83% lysine. From 121st to 210th days, the diet contained 3.40 Mcal·kg−1 ME, 15.00% crude protein and 1.15% lysine. The animals were allowed access to feed and water ad libitum, and lived under the same normal conditions.

Tissue collection

Animals were humanely sacrificed as necessary to ameliorate suffering and not fed the night before they were slaughtered. All the animals and samples used in this study were collected according to the guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals established by the Ministry of Agriculture of China.

Eight ATs from different body sites and two phenotypically distinct SMTs were rapidly separated from each carcass, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until RNA and DNA extraction. The eight ATs are divided into four groups: (1) three types of SATs (i.e. ASA, ULB and ILB near the last 3rd or 4th rib); (2) three types of VATs in the abdominal cavity (i.e. GOM, MAD and RAD); (3) one type of VAT in the thoracic cavity (i.e. PAD, which located between visceral and parietal pericardium); and (4) IAD, the adipose visible between muscle groups and beneath the muscle fascia in the hips. Two phenotypically distinct SMTs are LDM (typical white SMT) near the last 3rd or 4th rib and the intermediate section of PMM (typical red SMT).

Measurements of obesity-related phenotype

Measurements of pig body density, concentrations of 24 serum-circulating indicators of metabolism, adipocyte volume, myofiber cross-sectional area, myofiber type rate (fast/slow) and fatty acid composition are described in detail in Supplementary Methods.

MeDIP–seq

We randomly selected three pigs with a specific sex from each breed as biological replicates. And we have ten tissues for each individual, so in total 180 samples were sequenced separately. MeDIP DNA libraries were prepared following the protocol as our previous description54. Each MeDIP library was subjected to paired-end sequencing using Illumina HiSeq 2000 and a 50 bp read length. Details are listed in Supplementary Methods.

Identification of DMRs

After filtering the low quality reads, the MeDIP-seq data were aligned to the UCSC pig reference genome (Sscrofa9.2) using SOAP2 (Version 2.21)55. The genomic regions enriched in methylated CpGs across breeds (B-DMRs), sexes (S-DMRs) and tissues (T-DMRs) were identified using our newly developed method by calculating variation of single CpG. Additional details for the process are listed in Supplementary Methods.

Definition of genomic elements

We referred to the UCSC pig reference genome (Sscrofa9.2) annotation data for the identification of genomic elements. All 17,930 promoters (−2,200 to +500 bp) were classified into three types according to CpG representation as previously described22. There were 7,249 high CpG promoters (HCPs), 6,629 intermediate CpG promoters (ICPs) and 4,052 low CpG promoters (LCPs) (Fig. 4b). Each promoter of 2,700 bp length was divided into three regions as previously described28: proximal (P; −200 to +500 bp), intermediate (I; −200 to −1,000 bp), and distal (D; −1,000 to −2,200 bp). We obtained genomic locations of 38,778 CGIs and definitions of 21,533 Ensembl genes from the UCSC pig reference genome (Sscrofa9.2) as well as genomic locations of 803 pre-miRNAs based on our small RNA-seq results. We grouped CGIs into five classes on the basis of their distance to Ensembl genes or pre-miRNAs as previously described23 with some modifications (Fig. 4c). There are (1) 7,126 promoter CGIs (if a CGI ends after 1,000 bp upstream of a gene’s TSS, and starts before 300 bp downstream of a gene’s TSS); (2) 13,611 intragenic CGIs (if a CGI starts after 300 bp downstream of a gene’s TSS and ends before 300 bp upstream of a gene’s TES); (3) 2,305 3′ transcript CGIs (if a CGI ends after 300 bp upstream of a gene’s TES and starts before 300 bp downstream of a gene’s TES); (4) 16,954 intergenic CGIs (if a CGI starts after 300 bp downstream of a gene’s TES and ends before 1,000 bp upstream of a gene’s TSS); (5) 169 miRNA promoter CGIs (if there was a > 60% overlap of a CGI with 2 kb upstream of the pre-miRNA). There are overlaps between five classes of CGIs, due to the overlapping gene annotation at a specific genome coordinate. CGI shores were defined as extending up to 2 kb from CGIs.

We also identified the genomic locations of the 17,932 first exons, 14,760 first introns, 117,200 internal exons, 116,186 internal introns and 15,259 last exons of the 21,533 Ensembl genes, together with the 13,626 intergenic regions, 4,309,043 repeats and 59,385 SNPs by referring to the UCSC Genome Browser for pig.

MassArray

The DNA isolated from three biological replicates for each breed/sex/tissue type combination were pooled in equal quantities and treated with bisulphite using an EZ DNA methylation-Gold Kit (ZYMO research) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Quantitative methylation analysis of the DMRs was performed using the Sequenom MassARRAY platform (CapitalBio, Beijing, China) as described previously56. PCR primers were designed using the EpiDesigner software (Sequenom). The oligo sequences and the genomic coordinates of the amplicons across which DNA methylation was assessed in this study are given in Supplementary Table S2. The resultant methylation calls were analyzed with EpiTyper software v1.0 (Sequenom) to generate quantitative results for each CpG or an aggregate of multiple CpGs.

Gene expression microarray

Genome-wide gene expression analysis of 180 samples that corresponded to the samples used for MeDIP-seq were performed using the Agilent Pig Gene Expression Oligo Microarray (Version 2). Data analysis was performed with MultiExperiment Viewer (MeV). Details are listed in Supplementary Methods.

q-PCR

RNase-free DNase I (TaKaRa) was used for removal of genomic DNA from RNA samples used for microarray analysis. cDNA was synthesized using the oligo (dT) and random 6 mer primers provided in the PrimeScript RT Master Mix kit (TaKaRa). q-PCR was performed using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (TaKaRa) on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences used for the q-PCR are shown in Supplementary Table S3. All measurements contained a negative control (no cDNA template), and each RNA sample was analyzed in triplicate. Porcine ACTB, TBP and TOP2B were simultaneously used as endogenous control genes. Relative expression levels of objective mRNAs were calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

miRNA discovery and profiling

Eight ATs and two SMTs of the three female Landrace pigs were used for small RNA-seq. The construction of small RNA libraries and single-end sequencing in 36 bp reads using Illumina Genome Analyzer II, generated a total of 7.12 Gb reads for the ten libraries. The bioinformatics pipeline for miRNA discovery was carried out as our previous description57 with some improvements. Details are listed in Supplementary Methods. Our results extend the repertoire of pig miRNAome to 803 pre-miRNAs (174 known, 210 novel and 419 candidate), encoding for 1,014 mature miRNAs, of which 952 are unique (Supplementary Data 9).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Cheng Ye for help with data management, and Carol Yueng and Chris Heble for help with manuscript editing. This work was supported by grants from the National Special Foundation for Transgenic Species of China (2009ZX08009-155B and 2011ZX08006-003), the Specialized Research Fund of Ministry of Agriculture of China (NYCYTX-009), the Project of Provincial Twelfth 5 Years’ Animal Breeding of Sichuan Province (2011YZGG15) and the International Science & Technology Cooperation Program of China (2011DFB30340) to X.L., and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30901024) to M.L.

Footnotes

Accession codes: The high-throughput sequencing data and microarray data have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession numbers GSE30344 (MeDIP-seq data), GSE30343 (gene expression microarray data) and GSE30334 (small RNA-seq data).

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on http://www.nature.com/naturecommunications

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Kelly T, Yang W, Chen CS, Reynolds K, He J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 2008;32:1431–1437. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDougald OA, Burant CF. The rapidly expanding family of adipokines. Cell Metab. 2007;6:159–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. Adipocytes as regulators of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Nature. 2006;444:847–853. doi: 10.1038/nature05483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Despres JP, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2006;444:881–887. doi: 10.1038/nature05488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lusis AJ, Attie AD, Reue K. Metabolic syndrome: from epidemiology to systems biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:819–830. doi: 10.1038/nrg2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibrahim MM. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: structural and functional differences. Obes. Rev. 2010;11:11–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tran TT, Yamamoto Y, Gesta S, Kahn CR. Beneficial effects of subcutaneous fat transplantation on metabolism. Cell Metab. 2008;7:410–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satoor SN, et al. Location, location, location: Beneficial effects of autologous fat transplantation. Sci. Rep. 2011;1:81. doi: 10.1038/srep00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spurlock ME, Gabler NK. The development of porcine models of obesity and the metabolic syndrome. J. Nutr. 2008;138:397–402. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.2.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocha D, Plastow G. Commercial pigs: an untapped resource for human obesity research? Drug Discov. Today. 2006;11:475–477. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersson L. How selective sweeps in domestic animals provide new insight into biological mechanisms. J. Intern. Med. 2012;271:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heid IM, et al. Meta-analysis identifies 13 new loci associated with waist-hip ratio and reveals sexual dimorphism in the genetic basis of fat distribution. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:949–960. doi: 10.1038/ng.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Speliotes EK, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:937–948. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feinberg AP. Epigenomics reveals a functional genome anatomy and a new approach to common disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:1049–1052. doi: 10.1038/nbt1010-1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rakyan VK, Down TA, Balding DJ, Beck S. Epigenome-wide association studies for common human diseases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:529–541. doi: 10.1038/nrg3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feinberg AP, et al. Personalized epigenomic signatures that are stable over time and covary with body mass index. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010;2:49ra67. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefaucheur L, Ecolan P, Plantard L, Gueguen N. New insights into muscle fiber types in the pig. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2002;50:719–730. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hellman A, Chess A. Gene body-specific methylation on the active X chromosome. Science. 2007;315:1141–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1136352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber M, et al. Chromosome-wide and promoter-specific analyses identify sites of differential DNA methylation in normal and transformed human cells. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:853–862. doi: 10.1038/ng1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerkel K, et al. Genomic surveys by methylation-sensitive SNP analysis identify sequence-dependent allele-specific DNA methylation. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:904–908. doi: 10.1038/ng.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rankinen T, et al. The human obesity gene map: the 2005 update. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:529–644. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber M, et al. Distribution, silencing potential and evolutionary impact of promoter DNA methylation in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:457–466. doi: 10.1038/ng1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maunakea AK, et al. Conserved role of intragenic DNA methylation in regulating alternative promoters. Nature. 2010;466:253–257. doi: 10.1038/nature09165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takai D, Jones PA. Comprehensive analysis of CpG islands in human chromosomes 21 and 22. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:3740–3745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052410099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doi A, et al. Differential methylation of tissue- and cancer-specific CpG island shores distinguishes human induced pluripotent stem cells, embryonic stem cells and fibroblasts. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1350–1353. doi: 10.1038/ng.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irizarry RA, et al. The huan colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo- and hypermethylation at conserved tissue-specific CpG island shores. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:178–186. doi: 10.1038/ng.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji H, et al. Comprehensive methylome map of lineage commitment from haematopoietic progenitors. Nature. 2010;467:338–342. doi: 10.1038/nature09367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koga Y, et al. Genome-wide screen of promoter methylation identifies novel markers in melanoma. Genome Res. 2009;19:1462–1470. doi: 10.1101/gr.091447.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou X, Ruan J, Wang G, Zhang W. Characterization and identification of microRNA core promoters in four model species. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e37. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vrba L, Garbe JC, Stampfer MR, Futscher BW. Epigenetic regulation of normal human mammary cell type specific miRNAs. Genome Res. 2011 doi: 10.1101/gr.123935.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gertz J, et al. Analysis of DNA methylation in a three-generation family reveals widespread genetic influence on epigenetic regulation. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho E, Shimada Y. Formation of the epicardium studied with the scanning electron microscope. Dev. Biol. 1978;66:579–585. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cecil JE, Tavendale R, Watt P, Hetherington MM, Palmer CN. An obesity-associated FTO gene variant and increased energy intake in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:2558–2566. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Church C, et al. Overexpression of Fto leads to increased food intake and results in obesity. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:1086–1092. doi: 10.1038/ng.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iannello S, Milazzo P, Belfiore F. Animal and human tissue Na,K-ATPase in obesity and diabetes: A new proposed enzyme regulation. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2007;333:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200701000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biswas S, et al. Missense mutations in COL8A2, the gene encoding the alpha2 chain of type VIII collagen, cause two forms of corneal endothelial dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2415–2423. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.21.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X, et al. Differential expression of liver proteins between obesity-prone and obesity-resistant rats in response to a high-fat diet. Br. J. Nutr. 2011;106:612–626. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511000651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crosson SM, Khan A, Printen J, Pessin JE, Saltiel AR. PTG gene deletion causes impaired glycogen synthesis and developmental insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1423–1432. doi: 10.1172/JCI17975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun Y, Wang P, Zheng H, Smith RG. Ghrelin stimulation of growth hormone release and appetite is mediated through the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:4679–4684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305930101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du H, Dardzinski BJ, O’Brien KJ, Donnelly LF. MRI of fat distribution in a mouse model of lysosomal acid lipase deficiency. AJR. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2005;184:658–662. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.2.01840658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farooqi IS, et al. Clinical spectrum of obesity and mutations in the melanocortin 4 receptor gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1085–1095. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harvey NL, et al. Lymphatic vascular defects promoted by Prox1 haploinsufficiency cause adult-onset obesity. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1072–1081. doi: 10.1038/ng1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu ZL, Fritz ER, Reecy JM. AnimalQTLdb: a livestock QTL database tool set for positional QTL information mining and beyond. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2007;35:D604–D609. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun D, et al. miR-99 family of MicroRNAs suppresses the expression of prostate-specific antigen and prostate cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1313–1324. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu SW, Chen L, Man YG. miRNA biomarkers in breast cancer detection and management. J. Cancer. 2011;2:116–122. doi: 10.7150/jca.2.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fabrini R, et al. The extended catalysis of glutathione transferase. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:341–345. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang X, et al. Systematic genetic and genomic analysis of cytochrome P450 enzyme activities in human liver. Genome Res. 2010;20:1020–1036. doi: 10.1101/gr.103341.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chow KC, Lu MP, Wu MT. Expression of dihydrodiol dehydrogenase plays important roles in apoptosis- and drug-resistance of A431 squamous cell carcinoma. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2006;41:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang-Peronard JL, Andersen HR, Jensen TK, Heitmann BL. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and obesity development in humans: A review. Obes. Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iyer A, Fairlie DP, Prins JB, Hammock BD, Brown L. Inflammatory lipid mediators in adipocyte function and obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2010;6:71–82. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harrison BC, Leinwand LA. Fighting fat with muscle: bulking up to slim down. Cell Metab. 2008;7:97–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Braunschweig M, Jagannathan V, Gutzwiller A, Bee G. Investigations on transgenerational epigenetic response down the male line in F2 pigs. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li N, et al. Whole genome DNA methylation analysis based on high throughput sequencing technology. Methods. 2010;52:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li R, et al. SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1966–1967. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ehrich M, et al. Quantitative high-throughput analysis of DNA methylation patterns by base-specific cleavage and mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15785–15790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507816102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li M, et al. MicroRNAome of porcine pre- and postnatal development. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krzywinski M, et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.