Synopsis

Selenium is an essential trace element in mammals, but is toxic at high levels. It is best known for its cancer prevention activity, but cancer cells are more sensitive to selenite toxicity than normal cells. Since selenite treatment leads to oxidative stress, and the thioredoxin system is a major antioxidative system, we examined the interplay between thioredoxin reductase 1 (TR1) and thioredoxin 1 (Trx1) deficiencies and selenite toxicity in DT cells, a malignant mouse cell line, and the corresponding parental NIH3T3 cells. TR1 deficient cells were far more sensitive to selenite toxicity than Trx1-deficient or control cells. In contrast, this effect was not seen in cells treated with hydrogen peroxide, suggesting that the increased sensitivity of TR1 deficiency to selenite was not due to oxidative stress caused by this compound. Further analyses revealed that only TR1-deficient cells manifested strongly enhanced production and secretion of glutathione, which was associated with increased sensitivity of the cells to selenite. The data uncover a new role of TR1 in cancer that is independent of Trx reduction and compensated for by the glutathione system. The data also suggest that the enhanced selenite toxicity of cancer cells and simultaneous inhibition of TR1 can provide a new avenue for cancer therapy.

Keywords: Selenium cytotoxicity, Thioredoxin reductase 1, Thioredoxin, Glutathione, Cancer, Selenoprotein

INTRODUCTION

Selenium plays an important role in decreasing the incidence of cancer and other human diseases [1–4]. More recently, epidemiological and genetic studies, as well as various molecular approaches and mouse models, have implicated selenium-containing proteins (selenoproteins) in having roles in cancer prevention, including colon [5, 6], prostate [2, 7] and other cancer forms [8–10]. It should also be noted that small molecular weight selenocompounds, as well as selenoproteins, have been shown to play roles in cancer and other disease prevention and in-depth reviews have been written on this subject [11–13]. The fact that both these classes of selenium-containing components have anticarcinogenic properties has led to considerable debate in the selenium field regarding which forms of selenium (i.e., small molecular weight selenocompounds or selenoproteins) provide greater health benefits. In more recent years, selenoproteins have received by far more attention [14].

One selenoprotein that appears to participate in cancer prevention is thioredoxin reductase 1 (TR1) [15, 16]. TR1 is required for activation of the p53 tumor suppressor and for supporting other tumor suppressor activities [17], and is targeted by carcinogenic electrophilic compounds [18]. In addition, this selenoenzyme is one of the major redox regulators in mammalian cells and is expressed in all cell types, organs and tissues [15, 19, 20]. The targeted removal of TR1 in mice is embryonic lethal, and this protein also has roles in transcription, cell proliferation and DNA repair [21, 22]. The major function of TR1 in normal cells is to keep thioredoxin (Trx) in the reduced state; Trx then donates reducing equivalents to numerous cellular proteins, such as peroxiredoxins and methionine sulfoxide reductases [23]. In this manner, one of the major cellular redox systems, the Trx system, is regulated by TR1. The catalytic activity of TR1 that accounts for its function is governed by the selenocysteine (Sec) moiety, which is the C-terminal penultimate amino acid [24]. The above functions of TR1 provide strong evidence that this protein plays a highly significant role in maintaining cellular redox homeostasis and thus keeping cells in a healthy state. In addition, TR1 deficiency was reported to induce the cytoprotective transcription factor Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2), which is well known to control gene expression involved with phase II detoxification and antioxidant enzymes against oxidative stress or chemical challenge [25, 26], but the role of Trx in the regulation of Nrf2 is not completely understood.

TR1 can be considered as having a split personality in that it has roles in preventing cancer and also in promoting and/or sustaining cancer [10]. Indeed, TR1 is over-expressed in many tumors and cancer cells [19]. This enzyme has been designated as a target for cancer therapy, since a variety of potent inhibitors of this selenoenzyme inhibited cancer progression [9–20]. Moreover, certain anticancer drugs targeting TR1 decreased its activity in malignant cells, and consequently, changed the cancer properties of such cells (see references 27–29 and references therein). In addition, TR1 has been shown to be uniquely over-expressed, as compared to other mammalian selenoproteins, in a variety of cancer cell lines [19]. Furthermore, its targeted removal using RNAi technology altered cancer-related properties of malignant cells demonstrating that tumorigenic and metastatic properties of some cancer cell lines are dependent on TR1 expression [30]. Down-regulation of TR1 in a mouse cancer cell line driven by oncogenic k-ras has revealed that TR1-deficient cells lose self-sufficiency of growth, have a defective progression in their S phase and exhibit a reduced expression of an enzyme involved in DNA replication, DNA polymerase-α [31]. These latter studies have shown that TR1 has major roles in several of the hallmarks of cancer described by Hanahan and Weinberg [32], including metastasis and self-sufficiency in growth signals [30].

Selenite can be used as a source of selenium for cell growth, but at higher levels this compound is toxic. Cancer cells are known to be more sensitive to selenite toxicity than normal cells, and the relative sensitivities of different cancers to this selenium anion also vary [33, 34]. Other reports have shown an inverse relationship between resistance to cytotoxic drugs and sensitivity to selenite in cancer cells [35, 36]. Selenite is thought to induce apoptosis through oxidative stress [37, 38]. It has been proposed that the mechanism of selenite cytotoxicity involves the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through intracellular redox cycling with oxygen and cellular thiols [39]. However, the reason why cancer cells are more sensitive to selenite than normal cells is not clear. TR1 is known to have a broad substrate specificity, and selenodiglutathione (GS-Se-SG) and selenite were reported to be substrates for mammalian TR1 in biochemical studies [40, 41] suggesting a role of TR1 in selenium metabolism or selenium cytotoxicity.

To elucidate the role of TR1 in selenite toxicity in cancer cells, we compared the relative selenite sensitivities of DT cells, a cancer cell line derived from NIH3T3 cells [42], to the parental cell line. DT and NIH3T3 cells were made deficient in TR1 or Trx1 expression, and the effects of selenite and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) on the viability of these cells in relation to oxidative stress examined. These studies demonstrated that a TR1-deficient cancer cell line, designated DT/siTR1, was more sensitive to selenite than the corresponding Trx1-deficient or control cells and that the level of glutathione (GSH) in TR1-deficient cells was significantly increased compared to other cells. The data suggest that TR1 deficiency caused an increased production of GSH, which in turn caused an enhanced cytotoxic response to TR1 deficient cells.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Products were purchased as follows: H2O2, sodium selenite (Na2SeO3), reduced GSH, oxidized glutathione (GSSG), N-acetylcysteine (NAC), metaphosphoric acid, phthaldialdehyde, N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced tetra sodium salt (NADPH), and guanidine hydrochloride from Sigma; BCA protein assay reagent and SuperSignal West from Thermo Fisher Scientific; PVDF membrane, NuPage 4–12% Bis-Tris gels, trypan blue exclusion test assay, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), antibiotic-antimycotic solution and fetal bovine serum from Invitrogen Life Technologies; primary antibodies for Trx1, glutathione reductase (GSR) and glutathione synthetase (GSS) from Abcam; primary antibody for glutathione s-transferase α1 (GST-α1) from Detroit R&D; and anti-rabbit HRP conjugated secondary antibody from Cell Signaling Technology. 75Se was obtained from the Research Reactor Facility, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO. NIH3T3 cells and DT cells were obtained as previously reported [42].

Generation of TR1 and Trx1 deficient cells

Knockdown of TR1 in DT cells and preparation of the corresponding cell line encoding the pU6-m3 control vector that lacked the siRNA sequence were previously reported [31]. The control, stably transfected pU6-m3, in DT and NIH3T3 cells were produced as described [30]. Knockdown of TR1 and Trx1 in NIH3T3 cells and of Trx1 in DT cells were carried out as reported [30] with the following exceptions: Trx1 mRNA sequence, NM_011660, was surveyed for targeting its removal using the same strategy employed in generating TR1 knockdown DT cells [31]. The following nucleotide sequences were selected for targeting Trx1 mRNA: 5’-gctcagtcgtttagaacat-3’, 5’-gccactgctttaaggcaaa-3’ and 5’-ccaactgccatctgattat-3’.

Culture of mammalian cells and cell viability

NIH3T3 and DT cells were grown at 37°C, 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and antibiotic-antimycotic solution that contains 10,000 units/ml of penicillin, 10,000 µg/ml of streptomycin and 25 µg/ml of amphotericin B. 5×105 Cells were incubated overnight and then treated with sodium selenite or H2O2 at the concentrations given in the figures and/or figure legends for 24 h. NAC and GSH were added 30 min prior to sodium selenite treatment. Cell viability was measured by the trypan blue exclusion assay.

Quantification of GSH and GSSG

The concentrations of GSH and GSSG were measured as described previously using the fluorometric method [43]. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and homogenized with phosphate-EDTA buffer (0.1 M sodium phosphate and 5 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). Protein was quantitated using BCA protein assay reagent and precipitated with 5% (w/v) metaphosphoric acid. Samples were mixed with 90% (v/v) phosphate-EDTA buffer and 100 µg o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) to measure GSH concentration. To measure GSSG, cell extracts were treated with 4 mM N-ethylmaleimide for 30 min at room temperature and mixed with 0.09 N NaOH and 100 µg OPA. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Fluorescence was measured at excitation and emission wave-length of 350 nm and 420 nm, respectively. Pure GSH and GSSG were used to generate standard curves.

Western blot analysis, 75Se labeling and thin layer chromatography (TLC)

Techniques used for Western blot analysis have been described elsewhere [30, 31]. For 75Se labeling, cells were seeded onto a 6 well plate (3×105 cells/well) and labeled with 75Se (40 µCi/well) (University of Missouri, Columbia, MO) for 24h. Media samples were collected, the cells washed with PBS and then harvested. Media and lysate samples were separated by TLC using silica gel 60 F254 plates in chloroform:methanol:H2O (65:30:5). GSH and 75Se were used as controls and authentic labeled selenodiglutathione was prepared by incubating 75Se and GSH in buffer [9]. After running, the plate was stained with ninhydrin and the 75Se-glutathione conjugate in media and cell lysate was identified by autoradiography [30]. 75Se-Labeled proteins were electrophoresed and detected as described [30, 31].

RESULTS

Generation of TR1 and Trx1 deficient cells

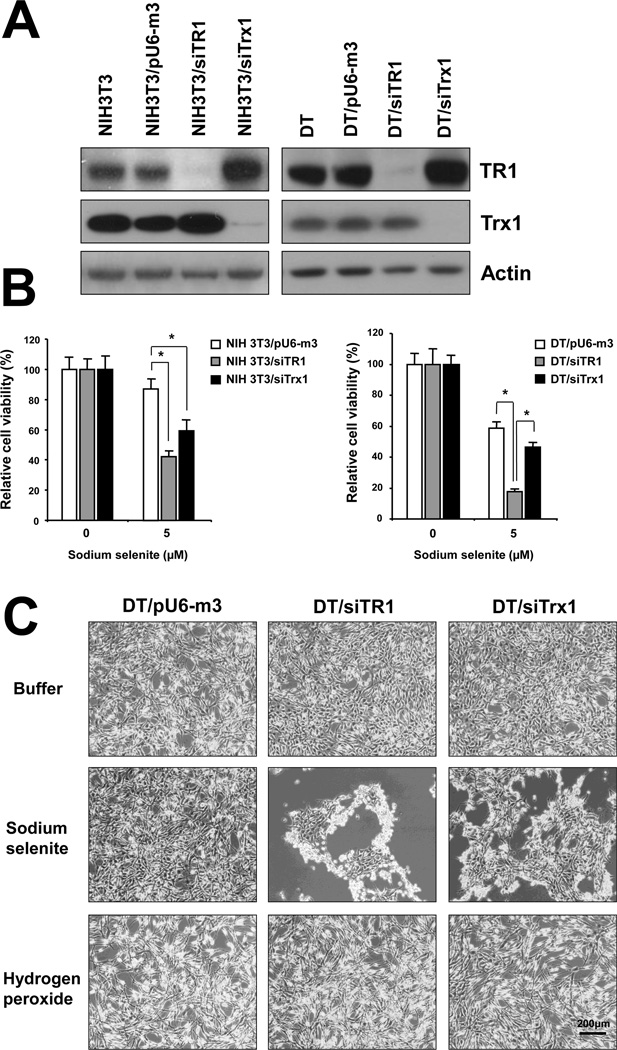

We targeted the removal of TR1 or Trx1 in NIH3T3 and DT cells by examining three sites in both TR1 and Trx1 mRNAs and selecting those most effective for protein removal [30, 31]. NIH3T3 and DT cells were then stably transfected with the control construct, pU6-m3, designated NIH3T3/pU6-m3 and DT/pU6-m3, respectively, and with the most effective siTR1 and siTrx1 knockdown constructs, designated NIH3T3/siTR1, DT/siTR1 and NIH3T3/siTrx1 and DT/siTrx1, respectively. More than 90% of TR1 and Trx1 appeared to be removed in stably transfected cell lines as determined by Western blotting (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Differential roles of TR1 and Trx1 in protecting cells from stress caused by selenite and H2O2 treatment.

(A) Expression of TR1 and Trx1 in NIH3T3 and DT TR1 and Trx1 knockdown cells. NIH3T3 cells (left panel) and DT cells (right panel) were stably transfected with pU6-m3 (control), siTR1 or siTrx1 vectors and expression of TR1 and Trx1 levels analyzed by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. Actin was used as a loading control. (B) Cell viability was determined by counting of live cell using trypan blue. NIH3T3 and DT cells stably transfected with control vector, or with siTR1 or siTrx1 knockdown vectors, were treated with 5 µM selenite for 24 h. Values show the viability ratio (%) compared with control cells and are the means ±S.D. of three independent experiments. *Indicates a significant difference (p<0.05). (C) DT control and TR1 and Trx1 deficient cells were treated with buffer (upper panel), 5 µM selenite (center panel) or 250 µM H2O2 for 24 h (lower panel), examined under the microscope and photographed. Bar (right, lowest panel) is 200 µm.

Effect of selenite and H2O2 on TR1 deficient cells

Since DT cells were derived from NIH3T3 cells [42], the parental cell line provided a normal control for DT cells. We therefore compared these two cell lines in subsequent experiments. The relative sensitivities of both cell lines to selenite were examined (Supplementary Figure 1). Significant differences were observed at 5 and 10 µM sodium selenite, wherein the parental cell line was little affected by 5 µM selenite, but the malignant cell line showed a pronounced inhibitory effect. At 10 µM, both cell lines were highly sensitive, but DT cells showed higher sensitivity. As 5 µM selenite appeared to be fairly non-toxic to NIH3T3 cells, but an effective toxin to DT cells, this level of selenite was used in subsequent studies.

We next examined the sensitivities of NIH3T3, DT and TR1- and Trx1-deficient cells to selenite, using two methods, the trypan blue exclusion method and the MTT assay. Toxicity of sodium selenite was increased in a dose-dependent manner in both cell lines as was similarly shown using both methods (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 2, respectively). Since significant differences between pU6-m3 control cells and TR1- and Trx1-deficient cells were observed at 5 µM (Figure 1B), this level of selenite was used in subsequent studies. Viability of TR1- and Trx1-deficient parental cells, NIH3T3/siTR1 and NIH3T3/siTrx1, respectively, upon treatment with selenite was similar and about half that of the control parental cell line (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 2). The sensitivity of DT/siTR1 cells to selenite was greater than DT/siTrx1 and DT/pU6-m3 control cells, whereas Trx1 deficient cells were only slightly more sensitive than control cells (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure2). In addition, DT/siTR1 cells were proportionately more sensitive to selenite relative to their control cells than were NIH3T3/siTR1 cells relative to their control cells (compare Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 2, upper panel to lower panel). The possible significance of these data is further considered below.

The finding that DT/siTR1 cells were far more sensitive to selenite than DT/siTrx1 cells was unexpected. This observation, the fact that TR1 is the primary reductant of Trx1 in normal mammalian cells [23], and the observation that selenite-treated malignant cells have been proposed to suffer from oxidative stress [44, 45], prompted us to determine whether the different sensitivities to selenite were due to cell death from oxidative stress or due to decreased growth rate. The three DT cell lines treated with buffer, selenite or H2O2 were examined (Figure 1C, upper, lower and middle panels, respectively). DT/siTR1 and DT/siTrx1 cells were dying when treated with selenite and the reduced viability observed in the presence of this compound was therefore due to cell death. On the other hand, cell morphologies of these three cell lines were similar in response to H2O2, suggesting that the reduced cell numbers observed in the presence of this oxidant were due to decreased growth rates.

Selenite treated TR1 and Trx1 deficient cells were further examined to assess whether the decreases in cell viabilities were caused by apoptosis (Supplementary Figure 3). The cell cycle was not affected by TR1 and Trx1 deficiency compared to control cells and the Sub-G1 population was not altered significantly by selenite treatment. These data suggest that the reduced viability of cells by selenite was not caused by apoptosis.

Effect of selenite and H2O2 on GSH metabolism

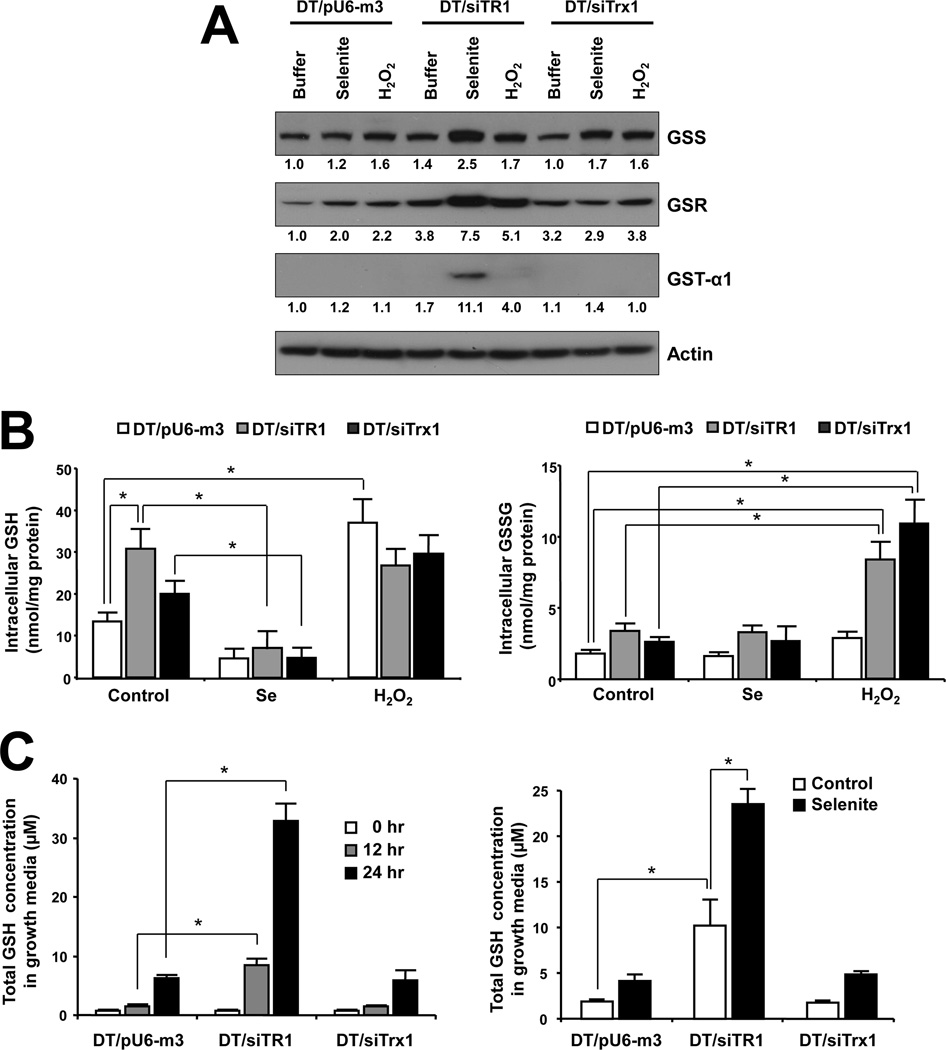

Since H2O2 did not appear to affect TR1- and Trx1-deficient cells, we examined whether selenite might affect the expression of enzymes involved in the GSH system, especially in TR1-deficient cells. Thus, mRNA levels of Gss, Gsr and Gst-α1 were examined in DT/siTR1 and DT/siTrx1 cells treated with selenite or H2O2 and compared to those in DT/pU6-m3 cells (Supplementary Figure 4). These enzymes are involved in the biosynthesis of GSH (GSS), reduction of GSSG (GSR), or conjugation of GSH to toxic metabolites (GST-α1). Only the TR1-deficient cells exposed to selenite showed a dramatic increase in levels of all three mRNAs compared to treated and untreated control cells (Supplementary Figure 4). To assess protein expression, Western blot analysis was performed on these enzymes showing that the enhanced levels of mRNAs for these enzymes also reflected an increase in their protein expression (Figure 2A). Expression levels of GSS in DT/siTR1 cells were higher than in DT/pU6-m3 and DT/siTrx1 cells. Furthermore, TR1-deficient cells exposed to selenite showed an increase in levels of all three enzymes, especially in expression of GST-α1 (compare Figure 2A, lane 5 to the other lanes). Trx1-deficient cells exposed to H2O2 showed higher levels of GSR and GSS than cells exposed to selenite (compare Figure 2A, lane 9 to lane 7 and 8, and Supplementary Figure 4A and 4B). Interestingly, the levels of enzymes involved in GSH metabolism in DT/siTR1 cells exposed to H2O2 were not as enriched as in cells exposed to selenite. These results suggest that TR1-deficient cells require higher GSH levels to compensate for the loss of TR1 than control and even Trx1-deficient cells, especially when they are exposed to selenite.

Figure 2. Effects of selenite and H2O2 on GSH metabolism.

(A) DT/pU6-m3, DT/siTR1 and DT/siTrx1 cells were left untreated or treated with 5 µM selenite or 250 µM H2O2 for 24 h and protein expression levels of glutathione synthetase (GSS), glutathione reductase (GSR), and glutathione S-transferase-α1 (GST-α1) examined by Western blotting. Actin was used as a control. The numbers under each panel show the relative band intensities that were normalized to the levels of actin expression. (B) Intracellular levels of GSH and GSSG were measured by the fluorometric method and expressed as nmol per mg of protein; values are the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. *Indicates significant difference (p<0.05). (B) Cells were incubated for 0, 12 or 24 h and media samples collected at each time point to examine GSH secretion. Media samples from cells treated with 5 µM selenite were prepared at 12 h to examine the effect of selenite on GSH secretion. The total GSH concentrations in media samples were analyzed fluorometrically. Values are the means ±S.D. of three independent experiments. *Indicates significant difference (p<0.05).

To further elucidate a possible protective role of GSH under conditions of selenite toxicity caused by TR1 deficiency, intracellular GSH and GSSG and extracellular GSH levels in DT/pU6-m3, DT/siTR1 and DT/siTrx1 cells grown in the absence or presence of selenite or H2O2 were examined by two different methods, the OPA histofluoroescence method [43] and the tietze recycling method [46] (Figure 2B, 2C and Supplementary Figure 5, respectively). Similar levels of intracellular GSH and GSSG were observed by both methods following exposure to selenite and H2O2 with the exception that (and as anticipated) the amount of GSSG in selenite treated cells measured by the tietze method manifested much higher levels of GSSG (Supplementary Figure 5) when compared with the data obtained by OPA method (Figure 2B). This was due to the fact that the tietze method uses glutathione reductase (GSR) which is known to detect Se-GSH conjugates such as GSSeSG in addition to GSSG, and GSR metabolizes both GSSG and GSSeSG [47]. Intracellular levels of GSH in TR1 deficient cells were approximately three times higher than in control cells. Selenite treatment totally depleted GSH in all three cell lines, but these cells had somewhat similar levels of GSH upon exposure to H2O2 (Figure 2B, left panel). Intracellular levels of GSSG were low and similar in the three cell lines of control and selenite exposed cells, but showed dramatic increases in DT/siTR1 and DT/siTrx1 cells exposed to H2O2 compared to the corresponding control cells (Figure 2B, right panel); therefore, the high amount of GSSG in malignant cells was likely due to a compromised Trx system. Extracellular or secreted levels of GSH in DT/siTR1 cells were more than 3 times higher under normal growth conditions, and selenite treatment triggered the increased secretion of GSH in all three cell lines, especially in TR1 deficient cells (Figure 2C).

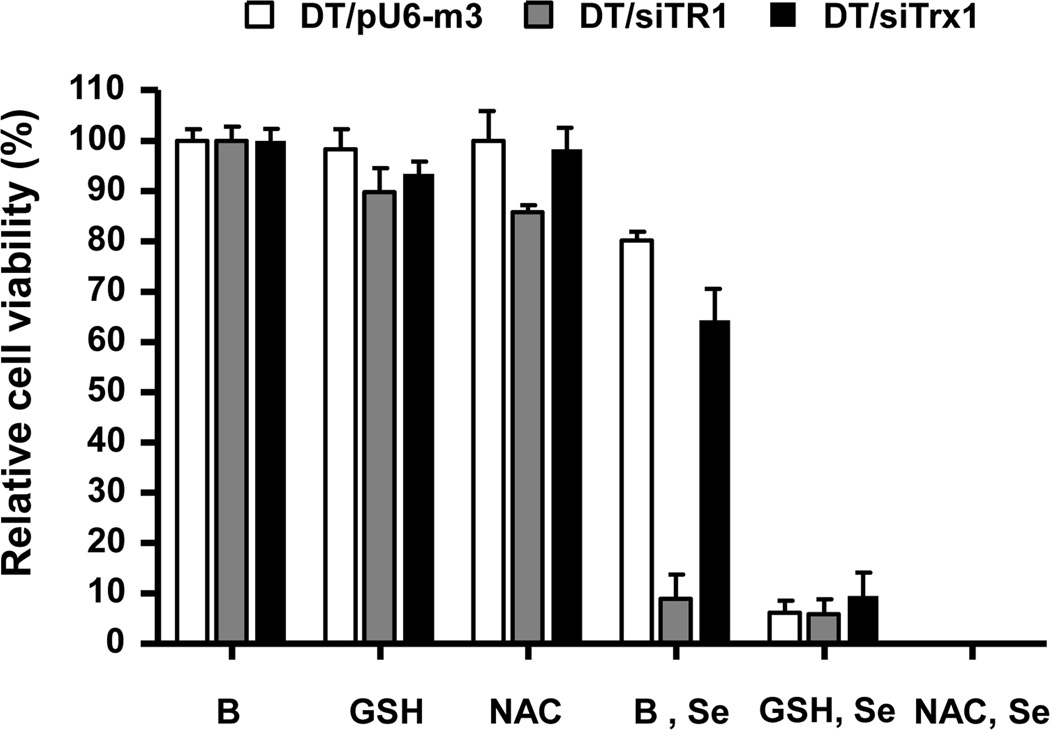

Effect of GSH on selenite toxicity

To verify the role of extracellular GSH in protection against selenite toxicity caused by TR1 deficiency, we pretreated cells with GSH or NAC which is known to affect the production of this antioxidant. All cell lines exposed to only GSH or NAC did not show observable differences in viability, but pretreatment of cells with GSH or NAC prior to selenite treatment caused massive cell death in all cell lines (Figure 3). The viability of all cell lines was less than 10% when compared with GSH or NAC treated cells not treated with selenite.

Figure 3. Effect of GSH and NAC on selenite-induced cell death.

DT/pU6-m3, DT/siTR1 and DT/siTrx1 cells were initially exposed to 0.5 mM GSH, 0.5 mM NAC or buffer (designated B in the figure), and 30 min later were treated with 5 µM selenite (designated Se in the figure). Viability was measured after 24 h of selenite treatment. Values show the viability ratio (%) compared with control and are the means ±S.D. of three independent experiments. *Indicates a significant difference (p<0.05).

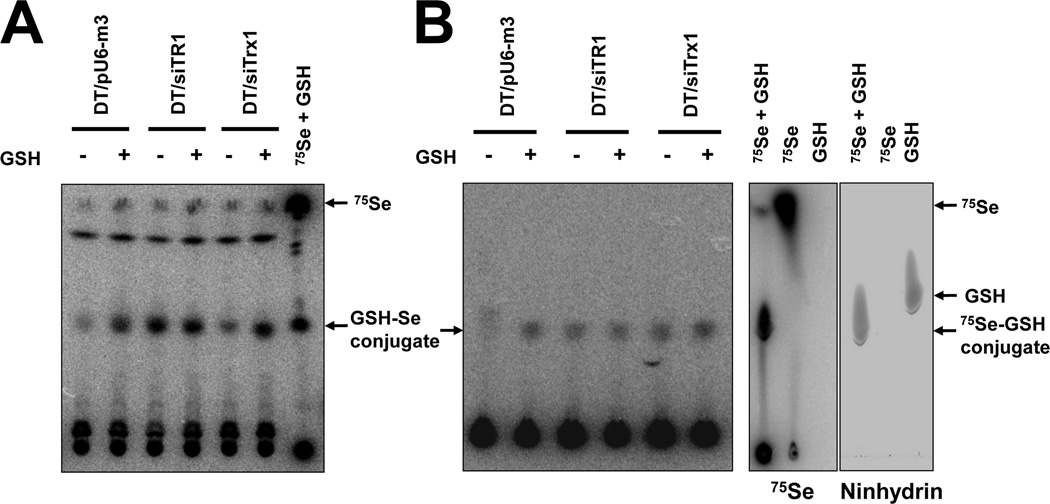

To examine the effect of extracellular GSH on selenite cytotoxicity, cells were treated with GSH and labeled with 75Se (Figure 4). 75Se-Conjugates were found in media and lysate samples by performing thin layer chromatography (Figure 4). The highest level of selenium glutathione conjugate (most likely selenodiglutathione (GS-Se-SG) (see Discussion)) was observed in TR1-deficient cells, and GSH treatment increased the selenium-glutathione conjugate levels, especially in the media of control and Trx-deficient cells (Figure 4A). DT/pU6-m3 control cells had an extremely low intracellular level of selenium-glutathione conjugate when compared with TR1 or Trx1 deficient cells, and GSH treatment significantly increased the intracellular level of selenium-glutathione conjugate in control cells but only slightly, if at all, in TR1 and Trx1 deficient cells (Figure 4B). As was previously reported, the addition of GSH resulted in increased levels of selenium-glutathione conjugate [40], but the increase did not appear to affect the expression level of selenoproteins (Supplementary Figure 6), whereas the addition of GSH or cysteine caused massive cell death in control, TR1 deficient and Trx1 deficient DT cells (Figure 3). These observations suggest that the increase in selenium-glutathione conjugate formation resulted in massive cell death in all the cell lines.

Figure 4. Formation of selenium-glutathione conjutgate in TR1 deficient cells.

DT/pU6-m3, DT/siTR1 and DT/siTrx1 cells were treated with GSH and metabolically labaled with 75Se for 24 hr, and media and cell extracts examined. (A) Extracellular and (B) intracellular selenite conjugated forms of GSH are shown which was observed by thin layer chromatography. In (C), authentic selenodiglutathione generated in the reaction containing 75Se and GSH is shown wherein 75Se (left panel) and ninhydrin stained GSH (right panel) were detected on the same thin layer chromatogram.

DISCUSSION

The Trx and GSH systems are regarded as major redox regulatory systems that maintain thiol redox homeostasis in mammalian cells. These systems are of particular importance to cancer cells since cancer cells are known to suffer from oxidative stress and rely on these protective redox systems for survival [45]. In fact, enhanced Trx and GSH systems in tumor and cancer cells, their possible interrelationship and interdependence, and their roles as targets in cancer therapy have been recognized and examined in several studies [48–49]. We have been interested in the role of TR1 in malignant cells, as this selenoenzyme is enriched in many cancer cells and tumors, and appears to have opposing roles in both preventing and promoting/sustaining cancer (see Introduction).

We first observed that DT cancer cells lacking TR1 were far more sensitive to selenite exposure than the corresponding Trx1 deficient or control cell lines as well as the corresponding parental NIH3T3 cells. This surprising finding suggested that the role of TR1 is not limited to the control of the redox state of Trx1. The sensitivity of TR1-deficient cells to selenite relative to control cells was also far greater in DT cells than in NIH3T3 cells (Figure 1B). It should be noted that there is a discrepancy in the protective role of TR1 against selenite cytotoxicity. It was previously reported that selenium and selenodiglutathione were reduced by mammalian TR1 in the presence of NADPH [40, 41], implicating TR1 in selenium metabolism and/or cytotoxicity. Cancer cells were found to express increased levels of TR1, but many cancer cell lines are more sensitive to selenite toxicity than normal cells [33, 34], suggesting the involvement of another pathway that is affected in TR1 deficient cancer cells. TR1 is known to have a role in protecting cells from oxidative stress mainly via reduction of Trx1 [23, 50, 51]. In this regard, the differences in the consequences of TR1 and Trx1 deficiency upon selenite or H2O2 exposure were especially interesting and unexpected.

To examine whether oxidative stress was involved in selenium cytotoxicity, we exposed control and TR1 or Trx1 deficient cell lines to sodium selenite or H2O2, wherein the latter agent was used as a positive control of oxidative stress. Different responses to those stresses were observed. The reduced viability of DT/TR1 and DT/Trx1 deficient cells following treatment with selenite was due to cell death, but it was not caused by apoptosis (Supplementary Figure 3). In contrast, their diminished cell numbers following treatment with H2O2 were due to decreased growth rates, even though H2O2 is known to induce severe oxidative stress (Figure 1C). The levels of ROS in these three cell lines (i.e., DT/TR1 deficient, DT/Trx1 deficient and DT control cells) was assessed by DCFDA which is a procedure used for detecting general ROS. There were no significant differences in the cell lines up to 6 h following treatment with selenite, but ROS increased in DT/siTR1 cells at 24 h following treatment (Supplementary Figure 7). The mechanism of the increase in intracellular ROS in late stages of selenite-induced cell death in TR1 deficient cells requires further examination. H2O2 appeared to increase GSH levels in control and Trx1 deficient cells. As expected, this treatment caused an accumulation of GSSG in TR1 and Trx1 deficient cells (Figure 2B), demonstrating that the GSH system decreased oxidative stress allowing cells to survive, and this phenomenon even occurred in cells having a functional Trx system. There was no significant change in GSSG levels by selenite treatment again suggesting that these cells were not suffering from significant oxidative stress or at least that selenite was simply acting through generation of H2O2.

We further investigated the role of GSH in protecting against selenite toxicity in DT/siTR1 cells by examining proteins involved in GSH production, the effect of selenite treatment on intracellular and extracellular GSH levels and the effect of increased levels of extracellular GSH on selenite cytotoxicity. GSH levels in DT/siTR1 cells were about three times higher under normal growth conditions, but selenite treatment depleted intracellular GSH in all cells (Figure 2B). It was previously reported that deletion of TR1 in mouse hepatocytes induced the cytoprotective transcription factor, Nrf2, and accordingly increased expression of phase II detoxification genes such as GSTs [25], but the role of Trx1 in the induction of Nrf2 by TR1 deficiency was not examined in detail. We found that expression of GSS, GSR and GST-α1 was increased by selenite treatment (Figure 2A) and that the extracellular levels of GSH, especially in DT/siTR1 cells, increased whereas intracellular levels of GSH were not restored by an increase in these enzymes (Figure 2B, left panel, and 2C, right panel). These observations showed that selenite treatment induced the production and secretion of GSH in DT/siTR1 cells, but not in DT/siTrx1 cells, suggesting that the regulation of GSH production and secretion by TR1 deficiency was not via Trx1. Pretreatment of GSH or NAC, which is known to induce the production of GSH, caused massive cell death in all cell lines (control, TR1 and Trx1 deficient cells), whereas GSH and NAC itself did not affect cell viability. These latter observations suggested that extracellular levels of GSH had a direct relationship with selenite-induced cell death and an increase in production and secretion of GSH in TR1-deficient cells that caused a higher sensitivity to selenite treatment. It has been proposed that selenium uptake and accumulation are crucial to specific selenite cytotoxicity in cancer cells, and the addition of extracellular GSH or thiol compounds along with selenite increased selenite cytotoxicity suggesting selenite uptake is controlled by the extracellular environment [39]. Recently, it was shown that selenodiglutathione (GS-Se-SG) was efficiently taken up by the vacuolar ABC-transporter, Ycf1p, and that overexpression of Ycf1p resulted in much higher selenite toxicity in yeast [52]. TR1-deficient cells produced and secreted much more GSH, manifested a high level of selenodiglutathione in the media and a much higher induction of GSH production and secretion following selenite treatment than control and Trx1-deficient cells. Thus, the increased sensitivity of TR1-knockdown cells apparently was caused by increased GSH production and secretion.

Mammalian TR1 has been reported to directly reduce selenite to selenide and Se0 species [41]. The latter selenium form may react with reduced glutathione to form GS-Se-SG that was proposed to be the major form of entry of selenocompounds into selenium metabolism [9, 53]. Furthermore, it was recently reported that other selenocompounds such as 2-butylselenazolidine-4(R)-carboxylic acid, 2-cyclohexylselenazolidine-4(R)-carboxylic acid and selenocystine were much more toxic to TR1-deficient cells [54], and BSO, which is known to inhibit GSH synthesis, has been shown to inhibit tumor growth in TR1 knockout mice and to cause cell death in TR1-deficient cultured cells [54, 55]. The involvement of Trx1, however, in these studies was not investigated.

In the absence of TR1 (or GSH as a second line of defense), a partially reduced selenium species could interact with reduced thiols in proteins whereby modifying critical cysteine residues and disrupting protein function. Therefore, further investigation of selenium metabolism in TR1- and Trx1-deficient cells following selenite exposure and the interplay of GSH and TR1 in selenium metabolism and selenium cytotoxicity may provide fruitful avenues for cancer therapeutic strategies [49, 50].

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Barbara J. Taylor and Subhadra Banerjee, FACS Core Facility, CCR, NCI, NIH, for their assistance with FACS analysis.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health NCI Intramural Research Program and the Center for Cancer Research (to D.L.H.), by the National Institutes of Health Grants GM065204 and CA080946 (to V.N.G.) and by Spanish Ministry of Sciences BFU2006-14267 (to S.C.).

Abbreviations Used

- GSH

Glutathione

- GSSG

Oxidized glutathione

- GSR

Glutathione reductase

- GSS

Glutathione synthetase

- GST

Glutathione S-transferase

- NAC

N-Acetyl cysteine

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- OPA

o-phthalaldehyde

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- Trx1

Thioredoxin 1

- TR1

Thioredoxin reductase 1

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Ryuta Tobe, Min-Hyuk Yoo, Noelia Fradejas and Bradley A. Carlson performed the experiments. Soledad Calvo, Vadim N. Gladyshev, Min-Hyuk Yoo and Dolph L. Hatfield planned the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript and the other authors, Ryuta Tobe, Noelia Fradejas and Bradley A. Carlson, also participated in planning the experiments, analyzing the data and writing the manuscript.

There are no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fleming J, Ghose A, Harrison PR. Molecular mechanisms of cancer prevention by selenium compounds. Nutr. Cancer. 2001;40:42–49. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC401_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. The Outcome of Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) reveals the need for better understanding of selenium biology. Mol. Interv. 2009;9:18–21. doi: 10.1124/mi.9.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung HJ, Seo YR. Current issues of selenium in cancer chemoprevention. Biofactors. 2010;36:153–158. doi: 10.1002/biof.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellinger FP, Raman AV, Reeves MA, Berry MJ. Regulation and function of selenoproteins in human disease. Biochem. J. 2009;422:11–22. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irons R, Tsuji PA, Carlson BA, Ouyang P, Yoo MH, Xu XM, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN, Davis CD. Deficiency in the 15-kDa selenoprotein inhibits tumorigenicity and metastasis of colon cancer cells. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 2010;3:630–639. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irons R, Carlson BA, Hatfield DL, Davis CD. Both selenoproteins and low molecular weight selenocompounds reduce colon cancer risk in mice with genetically impaired selenoprotein expression. J. Nutr. 2006;136:1311–1317. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.5.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumaraswamy E, Malykh A, Korotkov KV, Kozyavkin S, Hu Y, Kwon SY, Moustafa ME, Carlson BA, Berry MJ, Lee BJ, Hatfield DL, Diamond AM, Gladyshev VN. Structure-expression relationships of the 15-kDa selenoprotein gene. Possible role of the protein in cancer etiology. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:35540–35547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004014200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diwadkar-Navsariwala V, Prins GS, Swanson SM, Birch LA, Ray VH, Hedayat S, Lantvit DL, Diamond AM. Selenoprotein deficiency accelerates prostate carcinogenesis in a transgenic model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:8179–8184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508218103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selenius M, Rundlof AK, Olm E, Fernandes AP, Bjornstedt M. Selenium and the selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase in the prevention, treatment and diagnostics of cancer. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2010;12:867–880. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatfield DL, Yoo MH, Carlson BA, Gladyshev VN. Selenoproteins that function in cancer prevention and promotion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1790:1541–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brigelius-Flohe R. Selenium compounds and selenoproteins in cancer. Chem. Biodivers. 2008;5:389–395. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200890039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rayman MP. Selenium in cancer prevention: a review of the evidence and mechanism of action. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2005;64:527–542. doi: 10.1079/pns2005467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu J, Jiang C. Selenium and cancer chemoprevention: hypothese integrating the actions of Selenoproteins and selenium metabolites in epithelial and non-epithelial target cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2005;7:1715–1727. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatfield DL, Berry MJ, Gladyshev VN. Selenium: Its Molecular Biology and Role in Human Health. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; 2012. p. 598. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen P, Awwad RT, Smart DD, Spitz DR, Gius D. Thioredoxin reductase as a novel molecular target for cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2006;236:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Urig S, Becker K. On the potential of thioredoxin reductase inhibitors for cancer therapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2006;16:452–465. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merrill GF, Dowell P, Pearson GD. The human p53 negative regulatory domain mediates inhibition of reporter gene transactivation in yeast lacking thioredoxin reductase. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3175–3179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moos PJ, Edes K, Cassidy P, Massuda E, Fitzpatrick FA. Electrophilic prostaglandins and lipid aldehydes repress redox-sensitive transcription factors p53 and hypoxia-inducible factor by impairing the selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:745–750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lincoln DT, Ali Emadi EM, Tonissen KF, Clarke FM. The thioredoxin-thioredoxin reductase system: over-expression in human cancer. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:2425–2433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biaglow JE, Miller RA. The thioredoxin reductase/thioredoxin system: novel redox targets for cancer therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2005;4:6–13. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.1.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiermayer C, Michalke B, Schmidt J, Brielmeier M. Effect of selenium on thioredoxin reductase activity in Txnrd1 or Txnrd2 hemizygous mice. Biol. Chem. 2007;388:1091–1097. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalantari P, Narayan V, Natarajan SK, Muralidhar K, Gandhi UH, Vunta H, Henderson AJ, Prabhu KS. Thioredoxin reductase-1 negatively regulates HIV-1 transactivating protein Tat-dependent transcription in human macrophases. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:33183–33190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807403200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turanov AA, Kehr S, Marino SM, Yoo MH, Carlson BA, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Mammalian thioredoxin reductase 1: roles in redox homoeostasis and characterization of cellular targets. Biochem. J. 2010;430:285–293. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gladyshev VN, Jeang KT, Stadtman TC. Selenocysteine, identified as the penultimate C-terminal residue in human T-cell thioredoxin reductase, corresponds to TGA in the human placental gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:6146–6151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suvorova ES, Lucas O, Weisend CM, Rollins MF, Merrill GF, Capecchi MR, Schmidt EE. Cytoprotective Nrf2 pathway is induced in chronically txnrd 1-deficient hepatocytes. PLos One. 2009;4:e6158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kensler TW, Wakabayashi N, Biswal S. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007;47:89–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gandin V, Fernandes AP, Rigobello MP, Dani B, Sorrentino F, Tisato F, Bjornstedt M, Bindoli A, Sturaro A, Rella R, Marzano C. Cancer cell death induced by phosphine gold(I) compounds targeting thioredoxin reductase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;79:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marzano C, Gandin V, Folda A, Scutari G, Bindoli A, Rigobello MP. Inhibition of thioredoxin reductase by auranofin induces apoptosis in cisplatin-resistant human ovarian cancer cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;42:872–881. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan C, Shieh B, Reigan P, Zhang Z, Colucci MA, Chilloux A, Newsome JJ, Siegel D, Chan D, Moody CJ, Ross D. Potent activity of indolequinones against human pancreatic cancer: identification of thioredoxin reductase as a potential target. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009;76:163–172. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.055855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoo MH, Xu XM, Carlson BA, Gladyshev VN, Hatfield DL. Thioredoxin reductase 1 deficiency reverses tumor phenotype and tumorigenicity of lung carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:13005–13008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoo MH, Xu XM, Carlson BA, Patterson AD, Gladyshev VN, Hatfield DL. Targeting thioredoxin reductase 1 reduction in cancer cells inhibits self-sufficient growth and DNA replication. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Husbeck B, Nonn L, Peehl DM, Knox SJ. Tumor-selective killing by selenite in patient-matched pairs of normal and malignant prostate cells. Prostate. 2006;66:218–225. doi: 10.1002/pros.20337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menter DG, Sabichi AL, Lippman SM. Selenium effects on prostate cell growth. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:1171–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jonsson-Videsater K, Bjorkhem-Bergman L, Hossain A, Soderberg A, Eriksson LC, Paul C, Rosen A, Bjornstedt M. Selenite-induced apoptosis in doxorubicin-resistant cells and effects on the thioredoxin system. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;67:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bjorkhem-Bergman L, Jonsson K, Eriksson LC, Olsson JM, Lehmann S, Paul C, Bjornstedt M. Drug-resistant human lung cancer cells are more sensitive to selenium cytotoxicity. Effects on thioredoxin reductase and glutathione reductase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;63:1875–1884. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)00981-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nilsonne G, Sun X, Nystrom C, Rundlof AK, Potamitou Fernandes A, Bjornstedt M, Dobra K. Selenite induces apoptosis in sarcomatoid malignant mesothelioma cells through oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;41:874–885. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen CL, Song W, Pence BC. Interactions of selenium compounds with other antioxidants in DNA damage and apoptosis in human normal keratinocytes. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev. 2001;10:385–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olm E, Fernandes AP, Hebert C, Rundlof AK, Larsen EH, Danielsson O, Bjornstedt M. Extracellular thiol-assisted selenium uptake dependent on the x(c)- cystine transporter explains the cancer-specific cytotoxicity of selenite. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:11400–11405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902204106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bjornstedt M, Kumar S, Holmgren A. Selenodiglutathione is a high efficient oxidant of reduced thioredoxin and a substrate for mammalian thioredoxin reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:8030–8034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar S, Bjornstedt M, Holomgren A. Selenite is a substrate for calf thymus thioredoxin reductase and thioredoxin and elicits a large nonstoichiometric oxidation of NADPH in the presence of oxygen. EurJBiochem. 1992;207:435–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noda M, Selinger Z, Scolnick EM, Bassin RH. Flat revertants isolated from Kirsten sarcoma virus-transformed cells are resistant to the action of specific oncogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:5602–5606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.18.5602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hissin PJ, Hilf R. A fluorometric method for determination of oxidized and reduced glutathione in tissues. Anal. Biochem. 1976;74:214–226. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and cancer: have we moved forward? Biochem. J. 2007;401:1–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McEligot AJ, Yang S, Meyskens FL., Jr Redox regulation by intrinsic species and extrinsic nutrients in normal and cancer cells. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2005;25:261–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.25.050304.092633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rahman I, Kode A, Biswas SK. Assay for quantitative determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide levels using enzymatic recycling method. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:3159–3165. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bjornstedt M, Kumar S, Holomgren A. Selenodiglutathione is a highly efficient oxidant of reduced thioredoxin and a substrate for mammalian thioredoxin reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:8030–8034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corti A, Franzini M, Paolicchi A, Pompella A. Gamma-glutamyltransferase of cancer cells at the cross roads of tumor progression, drug resistance and drug targeting. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:1169–1181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Montero AJ, Jassem J. Cellular redox pathwas as a therapeutic target in the treatment of cancer. Drugs. 2011;71:1385–1396. doi: 10.2165/11592590-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arner ES, Holmgren A. The thioredoxin system in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2006;16:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holmgren A, Lu J. Thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase: current research with special reference to human disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;396:120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lazard M, Ha-Duong NT, Mounie S, Perrin R, Plateau P, Blanquet S. Selenodiglutathione uptake by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae vacuolar ATP-binding cassette transporter Ycf1p. FEBS. J. 2011;278:4112–4121. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoefig CS, Renko K, Kohrle J, Birringer M, Schomburg L. Comparison of different selenocompounds with respect to nutritional value vs. toxicity using liver cells in culture. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011;10:945–955. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poerschke RL, Moos PJ. Thioredoxin reductase 1 knockdown enhances selenazolidine cytotoxicity in human lung cancer cells via mitochondrial dysfunction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011;81:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mandal PK, Schneider M, Kolle P, Kuhlencordt P, Forster H, Beck H, Bornkamm GW, Conrad M. Loss of thioredoxin reductase 1 renders tumors highly susceptible to pharmacologic glutathione deprivation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9505–9514. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.