Abstract

Abscission explants of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) were treated with ethylene to induce cell separation at the primary abscission zone. After several days of further incubation of the remaining petiole in endogenously produced ethylene, the distal two-thirds of the petiole became senescent, and the remaining (proximal) portion stayed green. Cell-to-cell separation (secondary abscission) takes place precisely at the interface between the senescing yellow and the enlarging green cells. The expression of the abscission-associated isoform of β-1,4-glucanhydrolase, the activation of the Golgi apparatus, and enhanced vesicle formation occurred only in the enlarging cortical cells on the green side. These changes were indistinguishable from those that occur in normal abscission cells and confirm the conversion of the cortical cells to abscission-type cells. Secondary abscission cells were also induced by applying auxin to the exposed primary abscission surface after the pulvinus was shed, provided ethylene was added. Then, the orientation of development of green and yellow tissue was reversed; the distal tissue remained green and the proximal tissue yellowed. Nevertheless, separation still occurred at the junction between green and yellow cells and, again, it was one to two cell layers of the green side that enlarged and separated from their senescing neighbors. Evaluation of Feulgen-stained tissue establishes that, although nuclear changes occur, the conversion of the cortical cell to an abscission zone cell is a true transdifferentiation event, occurring in the absence of cell division.

We are of the view that the fundamental molecular mechanisms of cell differentiation in plants and animals are intrinsically similar but that, throughout the life of the organism, the majority of plant cells retain a freedom of commitment with respect to the choice of options for further cell determination (Osborne and McManus, 1986).

There is, however, good evidence that terminal commitment does occur in certain restricted cell types in higher plants. Those forming the aleurone layer in graminaceous seeds are one example, and, of particular interest to us, the cells that comprise leaf abscission zones are another. These cell types are confined to very precise positions within the plant and display a high degree of functional specialization with respect to hormonal cues. Once formed they do not differentiate further. In certain plants (bean [Phaseolus vulgaris] and Sambucus nigra), specific protein determinants have been identified in leaf abscission cells that are preferentially expressed compared with neighboring (nonabscission) tissue (McManus and Osborne, 1990a, 1990b, 1991). The presence of such determinants mark these cells as possessing a specific functional competence with respect to their neighbors.

The question arises as to whether cells from higher plants that retain a freedom of commitment can transdifferentiate to a different cell type, i.e. convert into another distinct cell type without cell division, or if there is always a requirement for prior cell division. Evidence from studies with plant cells and tissues in culture suggests that cells divide as part of a de-differentiation process (often to form callus) before new cell types (usually arising from organized apical regions) are formed (Schiavone and Racusen, 1990), although transdifferentiation of parenchyma cells directly into tracheary elements has been observed (Sugiyama and Komamine, 1990).

In the present study we provide evidence that cortical cells of mature bean petioles have the flexibility to convert directly into functionally competent and biochemically recognizable ethylene-responsive abscission cells and exhibit a gene expression of the new cell type. Further, this conversion occurs without the need for cell division.

Pertinent to our study is the organizational polarity of tissues that is reiterated as plants differentiate and develop. The concept that plant cells and mature tissues retain this inherent polarity (or axiality) throughout their life span is widely accepted (Schnepf, 1986; Warren Wilson and Warren Wilson, 1993), although the fundamental mechanisms by which this polarity is established and maintained are not understood. However, each cell is also the recipient of information from each of its neighbors and will respond according to the dictates of the signal and the flexibility of its own differentiation state. In this paper we show that transdifferentiation of cortical cells to abscission zone cells can be directed by a combination of auxin and ethylene inputs, the response to which is not restricted by the fixed axiality of the petiole tissue as a whole.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plants of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris var. Masterpiece) (Asmer Seeds Ltd., Leicester, UK) were grown in a greenhouse in Levington's Universal compost (Fisons, Suffolk, UK). The plants were given additional illumination with 400-W mercury vapor lamps to maintain long days (minimum 14 h), and the temperature was maintained at a minimum of 15°C. The first leaf pair, harvested when fully expanded (approximately 12–15 d), was used in experiments.

Secondary Abscission Assays

Explants, 1.5 cm long, were excised from the primary leaves to include the distal pulvinus, the abscission zone, and part of the petiole. These explants were supported on Perspex racks over 2% (w/v) sterile agar in glass containers, and all manipulations were performed in a sterile lamina flowhood. The explants were incubated in 10 μL L−1 ethylene at 24°C in continuous cool-white fluorescent light for 16 h, followed by 80 h in air, after which time the senescent and abscinded pulvini were removed and the remaining petioles were incubated in glass containers in which endogenous levels of ethylene accumulated (up to 3 μL L−1). Once secondary zones formed (at d 8), tissue from these explants was used (a) to determine β-1,4-glucanhydrolase activity and (b) for immune-recognition assays (by ELISA), utilizing an antiserum raised against the bean abscission zone cell-associated β-1,4-glucanhydrolase isoenzyme (pI 9.5). From the time of pulvinus separation (at d 4) until d 8, samples of petiole tissue were taken daily for light and transmission electron microscopy and for determinations of nDNA contents.

In separate experiments similar explants were incubated in ethylene (10 μL L−1) for 16 h and then in air for a further 48 h. At 64 h, the senescent and abscinded pulvini were removed, and 1 μL of a range of concentrations from 10 μm to 1 mm of a sterile solution of IAA or water was applied directly to the exposed surface of the primary abscission zone at 12-h intervals for 24 h. During these treatments and for a further 48 h, the explants were maintained at 24°C in continuous light either in air (with 0.25 m mercuric perchlorate in 2.5 m perchloric acid included to scavenge evolved ethylene) or in 10 μL L−1 ethylene. Explants were scored daily for the frequency of secondary abscission zone formation, and for those in (10 μL L−1) ethylene, the distance from the newly formed secondary abscission zone to the primary zone was measured.

Determination of β-1,4-Glucanhydrolase Activity

The viscosity assay as described by Wright and Osborne (1974) was used, with some minor modifications.

Sections approximately 1.0 mm thick were excised as appropriate from explants after separation of the pulvinus at the primary zone (at d 4), and after separation at the secondary zone (at d 8). Sections from 25 explants (approximately 120–150 mg fresh weight) were pooled and homogenized in 3 mL of 0.02 m phosphate buffer, pH 6.1, containing 1.0 m NaCl (for maximum extraction of the pI 9.5 zone-specific isoenzyme; Lewis and Koehler, 1979) and 5 mm DTT, the resultant slurry was centrifuged at 10,000g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was cleared by centrifugation at 25,000g for 30 min at 4°C. After equilibration to 25°C, aliquots (250 μL) of the cleared supernatant, diluted to a final volume of 1 mL in 0.05 m phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, containing 5 mm DTT, were mixed with 3 mL of 2% (w/v) carboxymethylcellulose (type 7HF, Hercules, Inc., Wilmington, DE) in the same buffer, and the mixture was incubated at 25°C. The viscosity of the mixture was recorded on mixing and, thereafter, at timed intervals. Activity is expressed as enzyme units, where 1 unit represents a percentage change in viscosity of 1 from the time of mixing until 60 min per 1 mL of original extract.

ELISA

Tissue extracts identical to those prepared for assay of β-1,4-glucanhydrolase activity were diluted in 50 mm sodium carbonate, pH 9.6, and coated onto 96-well Micro-ELISA plates (Dynatech Laboratories, Billinghurst, Sussex, UK). A rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against the pI 9.5 isoenzyme of β-1,4-glucanhydrolase purified from bean abscission tissue (kindly supplied by Dr. Sexton, Department of Biological Sciences, Stirling University, UK) was used as the primary antibody, and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Nordic Immunological Laboratories, Maidenhead, Berks, UK) was used as the secondary antibody. The peroxidase-bound peroxidase was quantified by the addition of 0.05% (w/v) o-phenylenediamine and 0.03% (v/v) H2O2 in 0.02 m sodium acetate, pH 5.0, and the developed color was measured at 495 nm using a Micro-ELISA MR 580 plate reader (Dynatech Laboratories).

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy was performed using a cryo-system developed by EM Technology (Hexland, Ltd., Oxford, UK), attached to a scanning electron microscope (model 505, Philips). Abscission explants with partial or complete cell separation at the secondary abscission zone were examined.

Light and Transmission Electron Microscopy

Explant tissue was fixed for 4 h in 3% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. After washing in buffer, the tissues were postfixed for 1 h in 1% (w/v) osmium tetroxide, washed, and then held in 1% (w/v) uranyl acetate for 18 h. The fixed tissue was dehydrated through an ethanol series and embedded in TAAB resin (TAAB Laboratory Equipment, Ltd., Reading, Berkshire, UK). For light microscopy, 2-μm sections were cut and stained in 1% (w/v) basic fuchsin or 1% (w/v) toluidine blue, and the sections were examined and photographed using an Axiophot microscope (Zeiss). For electron microscopy, thin sections were mounted on grids, stained with uranyl acetate followed by lead citrate, and examined at 100 kV using a Jeol 200 Ex electron microscope.

Quantification of nDNA

Sections of explant tissue from the different developmental stages of secondary zone formation were fixed overnight in ethanol:acetic acid (3:1, v/v). The nDNA was then hydrolyzed for 30 min in 5 n HCl at room temperature, and the tissue was rinsed in distilled water and stained with Feulgen reagent (BDH Chemicals, Poole, Dorset, UK) for 1 h in darkness at 25°C. After rinsing three times in a solution of 0.5% (w/v) KH2SO3 in 50 mm HCl and then once in water, the stained sections were softened in 45% (v/v) acetic acid for 10 min, rinsed with water, transferred to slides, and then squashed and mounted for viewing and quantification of nDNA in a M85 scanning microdensitometer (Vickers Instruments, York, UK). At least 200 nuclei were measured for each sample.

To obtain relative values for the diameter of the different nuclei, the slides were assessed using a marked graticule within the eyepiece of a binocular microscope at a magnification of ×200.

RESULTS

Conditions Leading to Secondary Abscission Zone Formation

To determine whether a secondary abscission zone could be induced as a transdifferentiation event, rather than the result of new cell divisions, we set up an explant system from the primary leaves of bean, in which we had previously ascertained that secondary abscission zones would form (Osborne and McManus, 1986).

The explants were induced to abscind at the primary zone by a brief treatment with ethylene, the shed pulvini were removed, and the remaining petioles were maintained in closed containers in which endogenously produced levels of ethylene accumulated (up to 3 μL L−1). After 7 to 8 d, distinct yellow:green junctions appeared in the petiole with a discrete zone of cell-cell separation between the distal yellow and proximal green portions (Fig. 1A). In these petioles the orientation of the senescent and nonsenescent tissue with respect to the separating cells was the same as that observed in vivo when a senescent pulvinus is shed at the primary abscission zone (i.e. a distal yellow pulvinus-proximal green petiole; Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

A, Cell-cell separation at secondary abscission zones that form between the distal yellow and proximal green tissue in petioles maintained in conditions in which endogenously produced auxin and ethylene accumulate. B, The naturally occurring leaf pulvinus:petiole abscission zone. C, Petioles treated with 1 mm IAA in the absence of ethylene. D, Cell-cell separation at the secondary abscission zone induced to form in petiole tissue by the application of 1 mm IAA in the presence of ethylene.

Evidence That Separation of Induced Yellow-Green Junctions Is a True Abscission Event

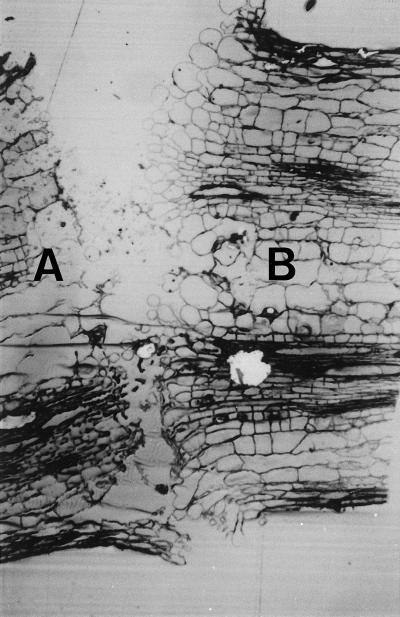

Microscopic examination of many yellow-green junctions (example shown in Fig. 2) revealed that, in common with separation at the primary zone, only cells of the green side of the induced zone enlarge to form turgid and rounded cells (Fig. 2, side B). Those of the adjacent yellow and senescing petiole eventually become collapsed and flaccid (Fig. 2, side A), and the epidermal cells on either the green or yellow side do not enlarge.

Figure 2.

Light micrograph of a separation between the distal yellow (A) and proximal green (B) tissue at a secondary abscission zone induced by endogenously produced auxin and ethylene (see Fig. 1A) (magnification ×47).

An induction of β-1,4-glucanhydrolase activity is concomitant with the initiation of separation in the primary leaf pulvinus-petiole abscission zone (Horton and Osborne, 1967; Wright and Osborne, 1974), and is attributable to an abscission zone-associated pI 9.5 isoenzyme (Sexton et al., 1980; Durbin et al., 1981). We show that β-1,4-glucanhydrolase activity is also induced in the secondary abscission zone at the site of the yellow-green junction by d 8 (Table I). The isoenzyme has been identified immunologically as the abscission-associated pI 9.5 isoform, with a high level of antibody binding to both extracts of primary and secondary zone tissue. No pI 9.5 enzyme induction and negligible antibody binding were observed to petiole tissues at a distance from the secondary abscission zone (Table I).

Table I.

Conversion of cortical cells to abscission cells directed by endogenous hormone levels

| Tissue | Absorbance Units in ELISAa | Enzyme Unitsb |

|---|---|---|

| d 0 | ||

| Freshly excised explants | ||

| Pulvinus | 0.06 ± 0.02c | 1.0 ± 0.1c |

| Abscission zone | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Petiole | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| d 4 | ||

| Explants after separation at the primary zone | ||

| Primary zone | 0.35 ± 0.0 | 36 ± 2.0 |

| Petiole | 0.07 ± 0.0 | 5.6 ± 1.9 |

| d 8 | ||

| Explants under endogenous ethylene | ||

| Primary zone | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 117 ± 15.0 |

| Yellow petiole | 0.07 ± 0.01 | NA |

| Secondary zone | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 157 ± 2.0 |

| Green petiole | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 23 ± 8.0 |

Activity of β-1,4-glucanhydrolase and immune recognition by the pI 9.5 isoenzyme antibody in extracts from tissues of the primary abscission zone at d 0 and 4 and tissues from the secondary abscission zone at cell-cell separation at d 8. NA, Not assayed.

Antibody recognition was detected using peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, and the absorbance was measured at 495 nm.

Activity is expressed as enzyme units, where 1 unit represents a percentage change in viscosity of 1 from the time of mixing until 60 min per 1 mL of original extract.

Values are ± range of replicates.

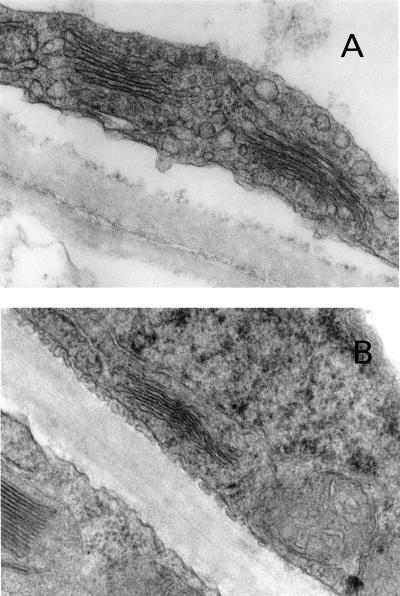

Ultrastructurally, the enlarging cells at primary abscission zones undergo cytoplasmic activation, including dilation of dictyosomes and enhanced vesicle formation. Such activity is not observed in other petiole cells at sites remote from the zone (Osborne et al., 1985). Ultrastructural examination of secondary zones generated in the present study show that cells at the proximal (green) side of the zone exhibited the highly dilated dictyosomes with many associated vesicles (Fig. 3A), similar to those observed in the cells at the proximal (green) side of primary zones. Cytoplasmic activation in these secondary zones was restricted to those green cells that enlarge and separate; it did not occur in other green cells (Fig. 3B) or in the yellow, nonseparating parts of the petiole (not shown).

Figure 3.

Transmission electron micrographs of the secondary abscission zone that forms between the distal yellow and proximal green tissue in petioles maintained in conditions in which endogenously produced auxin and ethylene accumulate (see Fig. 1A). A, Electron micrograph of a separating cell from the proximal (green) side of the newly formed zone. B, Electron micrograph of a nonseparating cell from the proximal (green) side of the newly formed zone, 12 rows of cells distant from the separating cells (magnification ×16,000).

Evidence That Secondary Zone Cell Formation Results from Cortical Cell Transdifferentiation

Light Microscopy

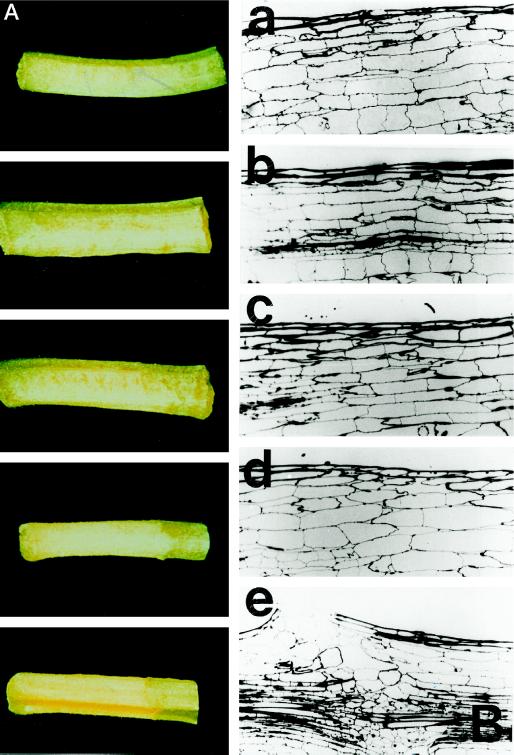

From the time of pulvinus shedding at the primary zone until separation of cells at the secondary zone, photographs of each petiole stage are shown (Fig. 4A). Samples of petiole tissue from each of these stages were excised and fixed for light microscopy, and a series of sections from the developing zones is shown in Figure 4B. At no stage during secondary zone development was any evidence for cell division observed (as defined by the deposition of cell plates) in either the cortex or in epidermal cells. Many samples of tissue have been examined in this way, and under all of the conditions for secondary zone formation that have been employed, none has shown evidence of any division or cell-plate formation in cells prior to, or during, yellow-green junction formation or during subsequent cell separation.

Figure 4.

A, Photographs of the developing stages (a–e) of distal (yellow) and proximal (green) junctions in petioles of abscinded explants. To induce secondary zone formation, abscinced explants were treated as described in Figure 1A. B, Photomicrographs of sections of cortex cut from the five stages of secondary zone development described in A (magnification ×100). a, Primary abscission just completed, petiole wholly green (d 0); b, slight loss of green color (d 2); c, beginning of formation of a yellow-green junction (d 4); d, yellow-green junction well defined (d 6); and e, cell separation at the yellow-green junction (d 8).

Determination of nDNA Content

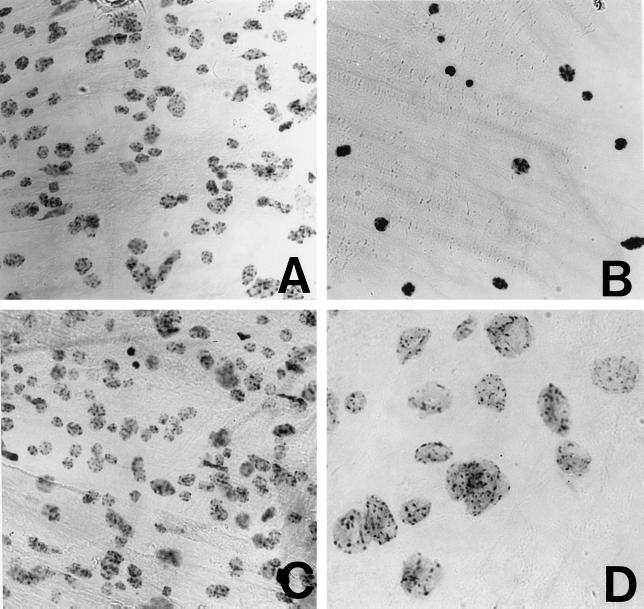

Samples of petiole tissue, similar to those used for light microscopy, were fixed and stained with Feulgen reagent for determinations of DNA content by microdensitometry. Throughout the period of the development of yellow-green junctions, no changes were found in terms of total DNA content of the nuclei in any part of the petiole. The relative DNA values remained similar to those in the petioles at the time of pulvinus shedding at the primary abscission zone (data not shown). Considerable changes were observed, however, in the size of the nuclei and in the distribution of chromatin and chromatin granules within the nuclei of the yellowing, green, and separating cells (Fig. 5). Nuclei in cortical tissue at the time of pulvinus shedding are shown in Figure 5A, with a mean relative diameter of 2.36 ± 0.57 units. As senescence proceeded in the yellow portion of the petiole, nuclei contracted in size (mean relative diameter: 2.03 ± 0.53 units) and chromatin became condensed (Fig. 5B). All cortical nuclei showed some slight enlargement (mean relative diameter: 3.89 ± 0.50 units) in those portions of the petiole that remained green (Fig. 5C), but in cells that enlarged and separated at the yellow-green junctions, nuclear volume greatly increased (mean relative diameter: 8.0 ± 1.45 units) and chromatin became highly dispersed (Fig. 5D). There was, however, no evidence of DNA replication or mitotic activity in cells at or neighboring the secondary zone, or in yellowing or green tissue of the petiole. These results, together with observations made with the light microscope, show that formation of secondary zone cells is a true transdifferentiation event.

Figure 5.

A, Feulgen-stained nuclei of cortical cells from petiole segments from which pulvini has just abscinded. B, Senescent (yellow) tissue at the time of secondary zone formation. C, Cells of green petiole tissue remote from the secondary zone. D, Cells of green tissue separating at the junction with yellow tissue at the secondary zone (magnification ×150).

Induction of Secondary Abscission Zones by Auxin and Ethylene

To explore the role of hormones in inducing these transdifferentiation events, we have manipulated those known to be involved in abscission control, i.e. ethylene and auxin, and recorded the frequency and position of secondary zone formation. To accomplish this, auxin was applied to the exposed petiole abscission cells at the primary abscission zone (after shedding of the senescent pulvinus), and ethylene was supplied in the ambient air. The position of secondary zone formation was then determined by the concentration of auxin applied and the presence or absence of ethylene (Table II). If ethylene was excluded, no new abscission zones were formed either in the presence or absence of auxin (Table II; Fig. 1C). When ethylene was present, the frequency of new zone differentiation was determined by the added auxin (Table II), with the location of the cortical-to-zone cell change dependent upon the concentration of IAA applied (Table III): the higher the concentration, the greater the distance between the primary zone and the induced secondary zone.

Table II.

Frequency of conversion of cortical cells to secondary abscission zone cells following applications of IAA and ethylene

| Explant Treatment | Time after Abscission at the Primary Zone | Explants with Secondary Zones and Cell-Cell Separation |

|---|---|---|

| h | % | |

| Ethylene (+IAA) | 24 | 0 |

| 48 | 15 | |

| 72 | 35 | |

| Ethylene (+H2O) | 24 | 0 |

| 48 | 0 | |

| 72 | 5 | |

| Air/MP (+IAA) | 24 | 0 |

| 48 | 0 | |

| 72 | 0 | |

| Air/MP (+H2O) | 24 | 0 |

| 48 | 0 | |

| 72 | 0 |

IAA (1 mm) or H2O was applied directly to the exposed cells of the separated primary abscission zone at 12-h intervals over 24 h. During treatment, and for a further 48 h, explants were incubated in ethylene (10 μL L−1) or air (with MP) and scored every 24 h for cell-cell separation at the green-yellow junction. MP, Mercuric perchlorate.

Table III.

Effect of applied IAA concentration on the positional formation of secondary zones

| IAA Concentration | Distance from Primary Zone |

|---|---|

| mm | |

| 0 | 1.3 ± 0.25a |

| 10 μm | 1.5 ± 0.25 |

| 100 μm | 3.0 ± 0.50 |

| 1 mm | 4.9 ± 0.60 |

IAA at the appropriate concentration or H2O was applied directly to the exposed cells of the separated primary abscission zone at 12-h intervals over 24 h. During treatment and for a further 48 h explants were incubated in ethylene (10 μL L−1) to induce cell separation at the secondary zone, and the distance along the petiole from the site of this induced zone to the primary zone was then measured.

Values are ± range of replicates.

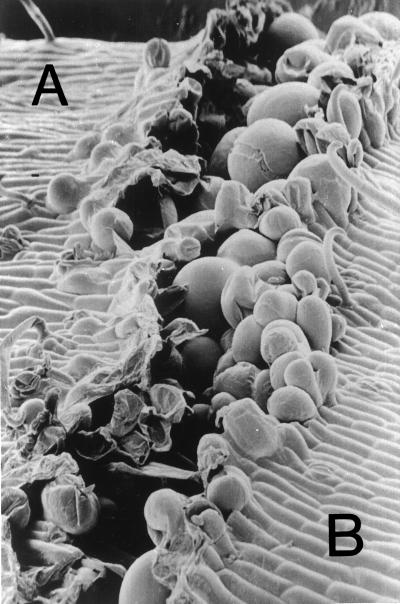

In contrast to the explants described in the previous section, the tissue below the auxin application and extending as far as the induced zone remained green and nonsenescent, but below the induced zone the petiole was senescent. Again, separation always occurred at a distal green and proximal yellow junction of cells (Fig. 1D). In the secondary zones induced by these treatments, therefore, the orientation of senescent and nonsenescent tissue was completely reversed compared with that of separation events normally occurring at a primary zone (compare Fig. 1D with Fig. 1A). The performance of these secondary zones, however, does not differ either in the induction of β-1,4-glucanhydrolase activity on the green side of the junction, with pI 9.5 immunological recognition (data not shown), or, in the restriction of cell enlargement, to only those cells of the green side of the junction (Fig. 6, side B). Again, no enlargement was observed in any of the epidermal cells (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Scanning electron micrograph of the secondary abscission zone that forms between the proximal yellow (A) and distal green (B) tissue of the petiole after incubation with applied auxin in the presence of ethylene (see Fig. 1D) (magnification ×170).

DISCUSSION

This study has explored the conversion of cortical cells of bean petioles into another distinct cell type, the abscission zone cell. The conversion has been shown to be directed by ethylene and auxin, and to take place in the absence of cell division, thus fulfilling the definition of transdifferentiation.

The differentiation of abscission zones in abnormal positions on stems, petioles, and branches can occur in vivo in response to tissue injury or infection (Addicott, 1982). For example, in the “shot-hole” response to fungal infection of Prunus amygdalus leaves, a disc of infected tissue from the leaf blade is shed from the surrounding palisade and mesophyll area by the formation of an encircling ring of separating cells (Samuel, 1927). When excised from the whole plant, certain parts of petioles and stems will also form secondary abscission zones in vitro (Addicott, 1982). Usually, the formation of these new zones is preceded by cell division, as in GA-induced shedding of cotton stems (Bornmann et al., 1968) and the auxin- and ethylene-regulated abscission in bean shoots (Webster and Leopold, 1972). However, the question as to whether cell division is a necessary prerequisite for such events has not been addressed directly.

The evidence we present here shows that in excised bean petioles a conversion of one cell type (the cortical cell) to another (the abscission zone cell) can take place without the advent of cell division. From examination using light microscopy of many sections through the developing region of the bean secondary abscission zone, we have found no evidence either for cell division or for the deposition of new cell plates. Using microdensitometry we found no increases in nDNA contents that might indicate an activation of cells to the S-phase or to the G2M phase. We cannot, however, say whether specific regions of DNA are replicated or amplified. It is possible that some DNA endoreduplication may occur, but these values would then fall within the range of variation of the DNA determinations by microdensitometry. The doubling of DNA content that accompanies the differentiation of an abscission cell at the base of the fruit in Ecballium elatarium (Wong and Osborne, 1978) does not occur as part of secondary zone formation in bean.

One of the few well-characterized examples of transdifferentiation in plants is the conversion of parenchyma cells into tracheary elements (for a review, see Sugiyama and Komamine, 1990). There, the use of specific inhibitors showed that formation of the mitotic spindle or DNA replication is not required for transdifferentiation, but “repair-type” synthesis of nDNA was a necessary prerequisite. An unscheduled DNA repair synthesis may accompany our bean cortical cell transdifferentiation, but we can exclude S-phase DNA synthesis. However, changes in the nuclei of the differently responding tissues clearly do take place. Those of the senescing tissue become progressively smaller and pycnotic, whereas cells of the newly forming abscission zone enlarge, and just prior to and at separation their nuclei exhibit the dispersed chromatin of highly active cells. These secondary zone cells, therefore, give every indication of an induced and increased genomic activity.

In common with transdifferentiated animal cells (Okada, 1983; Kineman et al., 1992; Patapoutian et al., 1995), we also observed a change in gene expression with the production of a marker protein (diagnostic for abscission cells) that accompanied the conversion of cortical cells to abscission cells. Upon separation at the primary zone, the immunologically distinct and abscission-associated pI 9.5 isoform of β-1,4-glucanhydrolase is newly expressed but only in abscission cells and their close neighbors and not in other cortical cells of the petiole. However, when these cortical cells are converted to abscission cells, they too express the specific pI 9.5 isoform of β-1,4-glucanhydrolase. Again, expression of the enzyme is confined to only the secondary abscission zone and is not detected in the other cells of the petiole. This biochemical and immunological evidence, taken together with the absence of cell division, confirms that this cortical-to-abscission cell conversion is a true transdifferentiation event.

In demonstrating the flexibility of cortical cells to transdifferentiate to committed abscission cells, we have shown that the conversion is not dependent on the orientation in which the green and senescent tissue develops in the petiole. If the transdifferentiation of cortical cells occurred only when the distal tissue became senescent and the proximal tissue remained green (as in separation of naturally occurring abscission zones), then one could conclude that a directional signaling or a polarity of perception or response operates. However, our experiments show the contrary. If the distal tissue is retained green and the proximal tissue becomes senescent, it is still the green cells at the junction with the senescing tissue that transdifferentiate. In other words, it is not critical to achieving the transdifferentiation response whether the distal or proximal tissue becomes senescent. Rather, the specific requirement appears to be the generation of a juxtaposition of green and senescing cells, irrespective of their orientation within the overall morphological axiality of the petiole. This apparent absence of directional perception and response to particular signals from their neighbor cells does not conflict with the concept that all cortical cells possess an established basipetal polarity (or axiality) in common with other cells in the plant body (Sachs, 1991; Warren Wilson and Warren Wilson, 1993).

At present the chemical nature of the signals that are transmitted between the adjacent senescent and nonsenescent petiole tissues has not been characterized, although we have established that ethylene provides one of the requirements for transdifferentiation and that the auxin concentration can provide positional information.

In analysis of extracts of bean explants (data not presented here), we have shown that applied 14C-IAA is conjugated in the petiole tissue (probably to IAA-aspartate) within 6 h. This could, as Hangarter and Good (1981) suggest, then be the source for a slow release of free IAA. In our IAA-treated petioles, in which the apical region remains green, a release of free IAA could be responsible for maintaining a region of tissue proximal to the point of IAA application in a green and nonsenescent condition, and, as we have observed, the concentration of IAA applied determines the length of tissue that is retained green. Warren Wilson et al. (1986) have described a mathematical model for Impatiens sultanii that accommodates such positional differentiation of abscission zones regulated by the concentration of auxin applied.

In this study we conclude that certain mature cells of higher plants retain a flexibility for direct transdifferentiation to functionally specialized and committed cell types. In the example we describe, cortical cells of the bean leaf petiole are seen to be sufficiently uncommitted to be converted into fully competent, terminally differentiated abscission zone cells. Further, we propose that certain cells, such as cortical cells, which retain differentiation flexibility, can undergo positional transdifferentiation independently of the distal-proximal axiality of the tissue.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by a New Zealand Ministry of Research, Science, and Technology Marsden Fund grant (no. MAU 509) to M.T.M.

LITERATURE CITED

- Addicott FT. Abscission. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bornmann CH, Addicott FT, Lyon JL, Smith DE. Anatomy of gibberellin-induced stem abscission in cotton. Am J Bot. 1968;55:369–375. [Google Scholar]

- Durbin ML, Sexton R, Lewis LN. The use of immunological methods to study the activity of cellulase isozymes in bean leaf abscission. Plant Cell Environ. 1981;4:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hangarter RP, Good NE. Evidence that IAA conjugates are slow release sources of free IAA in plant tissues. Plant Physiol. 1981;68:1424–1427. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.6.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton RF, Osborne DJ. Senescence, abscission and cellulase activity in Phaseolus vulgaris. Nature. 1967;214:1086–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Kineman RD, Faught WJ, Frawley S. Steroids can modulate transdifferentiation of prolactin and growth hormone cells in bovine pituitary cultures. Endocrinology. 1992;130:3289–3294. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.6.1597141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis LN, Koehler DE. Cellulase in the kidney bean seedling. Planta. 1979;146:1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00381248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus MT, Osborne DJ. Evidence for the preferential expression of particular polypeptides in leaf abscission zones of the bean Phaseolus vulgaris L. J Plant Physiol. 1990a;136:391–397. [Google Scholar]

- McManus MT, Osborne DJ. Identification of polypeptides specific to rachis abscission zone cells of Sambucus nigra. Physiol Plant. 1990b;79:471–478. [Google Scholar]

- McManus MT, Osborne DJ. Identification and characterisation of an ionically-bound cell wall glycoprotein expressed preferentially in the leaf rachis abscission zone of Sambucus nigra L. J Plant Physiol. 1991;138:63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Okada TS. Recent progress in studies of transdifferentiation of eye tissues in vitro. Cell Diff. 1983;13:177–183. doi: 10.1016/0045-6039(83)90087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne DJ, McManus MT. Flexibility and commitment in plant cells during development. Curr Topics Devel Biol. 1986;20:383–386. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60677-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne DJ, McManus MT, Webb J. Target cells for ethylene action. In: Roberts JA, Tucker GA, editors. Ethylene and Plant Development. London: Butterworths; 1985. pp. 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Patapoutian A, Wold BJ, Wagner RA. Evidence for the developmentally programmed transdifferentiation in mouse esophageal muscle. Science. 1995;270:1818–1822. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs T. Pattern Formation in Plant Tissues. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel G. On the shot-hole disease caused by Clasterosporium carpophilum and on the shot-hole effect. Ann Bot. 1927;41:375–404. [Google Scholar]

- Schiavone FM, Racusen RH. Microsurgery reveals regional capabilities for pattern re-establishment in somatic carrot embryos. Dev Biol. 1990;141:211–219. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90116-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnepf E. Cellular polarity. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1986;37:23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton R, Durbin M, Lewis LN, Thompson WW. Use of cellulase antibodies to study leaf abscission. Nature. 1980;283:873–874. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama M, Komamine A. Transdifferentiation of quiescent parenchyma cells into tracheary elements. Cell Diff Dev. 1990;31:77–87. doi: 10.1016/0922-3371(90)90011-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren Wilson J, Warren Wilson PM. Mechanisms of auxin regulation of structural and physiological polarity in plants, tissues, cells and embryos. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1993;20:555–571. [Google Scholar]

- Warren Wilson PM, Warren Wilson J, Addicott FT, McKenzie RH. Induced abscission sites in internodal explants of Impatiens sultanii: a new system for studying positional control. Ann Bot. 1986;57:511–530. [Google Scholar]

- Webster BD, Leopold AC. Stem abscission in Phaseolus vulgaris explants. Bot Gaz. 1972;133:292–298. [Google Scholar]

- Wong CH, Osborne DJ. The ethylene-induced enlargement of target cells in flower buds of Ecballium elaterium (L.) A. Rich. and their identification by the content of endoreduplicated nuclear DNA. Planta. 1978;139:103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wright M, Osborne DJ. Abscission in Phaseolus vulgaris: the positional differentiation and ethylene-induced expansion of specific cells. Planta. 1974;120:163–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00384926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]