Abstract

Deep sequencing can accurately measure the relative abundance of hundreds of mutants in a single bulk competition experiment, which can give a direct readout of the fitness of each mutant. Here, we describe a protocol that we previously developed and optimized to measure the fitness effects of all possible individual codon substitutions for 10 amino acid regions of essential genes in yeast. Starting with a conditional strain (i.e., a temperature sensitive strain), we describe how to efficiently generate plasmid libraries of point mutants that can then be transformed to generate libraries of yeast. The yeast libraries are competed under conditions that select for mutant function. Deep sequencing analyses are used to determine the relative fitness of all mutants. This approach is faster and cheaper per mutant compared to analyzing individually isolated mutants. The protocol can be performed in ~4 weeks and many 10 amino acid regions can be analyzed in parallel.

Keywords: point-mutant, fitness, deep sequencing, EMPIRIC, selection coefficient

Introduction

Evolution is a critical principle for interpreting and understanding biology. Evolutionary processes have shaped life in its present state and continue to mediate future population trajectories. The basic rule of evolution is competition, and fitness is the measure of individual competitive advantage/disadvantage. Genetic mutations are a dominant mechanism impacting fitness. The relationship between genetic mutations and fitness describes the raw evolutionary potential available to organisms. Here we describe a method that we refer to as EMPIRIC (Exceedingly Methodical and Parallel Investigation of Randomized Individual Codons) to systematically generate all possible point mutations in regions of important genes and quantify the fitness effect of each mutant1.

Many previous methods have been utilized to analyze the fitness effects of mutations. These methods fall broadly into two classes: population-genetic based inferences from sequence analyses of naturally-evolving populations2, 3, and direct fitness measurements of mutants4, 5. Population genetic models combined with polymorphism data provide routes to understand recent selection in all current organisms. However, mutations that cause a selectable fitness effect can be challenging to distinguish from hitchhiking mutants at linked genetic loci6. In contrast, experimental fitness competitions have the benefit of directly measuring fitness effects of specific mutations, though they cannot be applied to all organisms.

Experimental fitness measurements often involve isolating specific mutants and following their growth properties for multiple generations. These analyses are ideally suited for organisms that can be easily manipulated genetically and that have short generation times such as microbes. Indeed, the ability to genetically manipulate S. cerevisiae enabled systematic analyses of the fitness of single gene knockouts and the identification of essential genes7. The yeast deletion strains were generated with a unique DNA sequence or barcode bracketed by common primer sites for each gene knockout. These barcodes enable the relative abundance of each mutant to be monitored using PCR and sequencing. This approach enables quantitative analyses of relative fitness from bulk cultures of knockout strains. The fitness effects of knockouts provides useful insights, but it does not provide direct information on the fitness effects of many types of mutations that occur during natural evolution including point mutations.

Analyzing the fitness effects of point mutations is relevant to biology because they are a common form of mutation in evolution. Point mutations that lead to drug resistance have been extensively analyzed8. Drug-resistance mutations can be readily identified from both natural/clinical isolates and from laboratory selection experiments. The fitness effects of mutations in drug-resistant genes are frequently analyzed based on a dose-response curve. The large magnitude of growth changes associated with drug-resistant mutations facilitates their analysis and represents a stringent selection pressure.

Many genes are involved in adaptation to less stringent selection pressures9 than drug-resistance. Because the fitness changes are small relative to drug-resistance mutations, analyzing mutant fitness effects in the majority of genes requires accurate measurements of relative growth, and careful control of genetic background. Both growth curves of individual strains5 and binary competition experiments between fluorescently-labeled strains4 enable accurate measurement of the fitness effects of one mutant per culture. Using isolated individual mutations, alanine scanning has been used to identify hot-spots for protein function10.

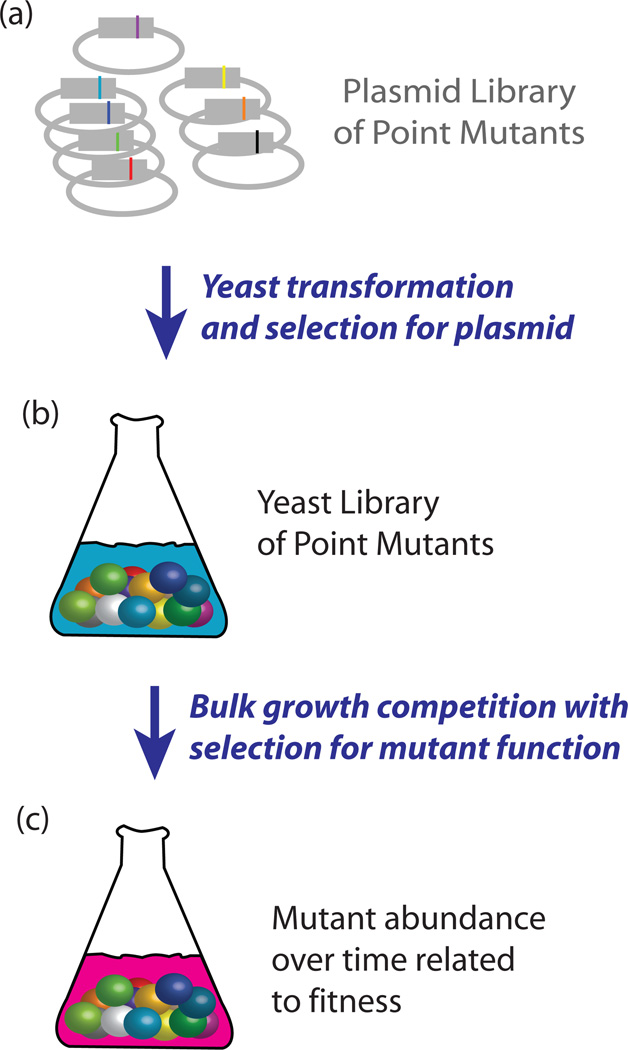

We developed the EMPIRIC approach to monitor the relative abundance of saturation point-mutants in a single bulk culture (Figure 1) with very high signal to noise1. This sequencing approach is similar in concept to the barcoded knockout collection7, as well as methods developed to analyze binding function of larger and more complex libraries using affinity isolation approaches11–13. In all three of these approaches, sequencing is utilized to monitor the relative abundance of mutants after the application of a selective pressure. In the knockout collection, mutants are identified by a unique barcode between universal primer binding sites. The affinity isolation approaches have been able to interrogate larger mutant libraries including many double mutants11, and are well-suited where broad sampling of double mutants are desired. In the EMPIRIC approach, the libraries are constructed to contain only point-mutants that are quantified directly using focused deep sequencing of mutated regions. This approach results in a strong sequencing signal for all possible point mutants, and it is ideally suited for applications where accurate and systematic measurements of point-mutant function or fitness are desired. While the initial application of EMPIRIC was analyzing the effect of mutants in Hsp90 on yeast growth1, the protocol could be modified to analyze growth in other genetically tractable systems (i.e. cancer cells and viruses) as well as for in vitro function utilizing display approaches11. In addition, we have found that throughput can be dramatically increased by analyzing multiple regions in parallel. We have performed parallel analyses of 8 separate 10-amino acid regions in the same four week time period required to analyze one region (unpublished data, BR). The maximum size of region that we have analyzed by EMPIRIC is currently 10-amino acids. The size of a region that can be accurately analyzed is constrained by sequencing read-length and accuracy.

Figure 1.

Bulk competition of libraries of point mutants in yeast. (a) Plasmid libraries are transformed into yeast. (b) Yeast that have taken up a plasmid are selected for and amplified. (c) Selection pressure is applied to the library copy of the mutated gene and samples are collected over time in bulk-competition.

Overview of the EMPIRIC method

The EMPIRIC method is designed to measure the competitive advantage or disadvantage of point mutants in high-throughput. Efficient analyses of mutants are facilitated by three main components: a rapid strategy to generate saturation mutants at consecutive amino acid positions in a gene; synchronized application of selection pressure to all mutants in a mixed competition experiment; and accurate measurement of the relative abundance of each mutant using deep sequencing. We use a cassette ligation strategy to efficiently generate mutant libraries. This stage involves DNA manipulations including PCR, ligations, and bacterial transformations. In order to synchronize selection pressure, we use a conditional yeast strain such as a temperature sensitive strain. This stage involves yeast microbiological techniques including transformation and growth in liquid culture. We use a deep sequencing approach to measure the abundance of each mutant. This stage involves isolation of DNA from yeast, DNA manipulations including PCR to generate focused libraries for sequencing, and bio-informatic analyses of the resulting sequencing data.

Experimental Design

In order to accurately measure the relative abundance of all possible point mutants for regions of genes using deep sequencing, the EMPIRIC approach was developed with careful consideration of signal to noise. Signal is the relative abundance of a mutant in a library. Noise comes from mis-reads that distort the measured abundance of a mutant from its actual abundance in the library. In library generation, the goal is to have all mutants present at similar abundance. In the growth competition, the goal is to rapidly analyze mutants under selection while minimizing the potential for secondary adaptive mutations. In analyzing the library, the goal is to minimize noise from mis-reads.

Mutant abundance

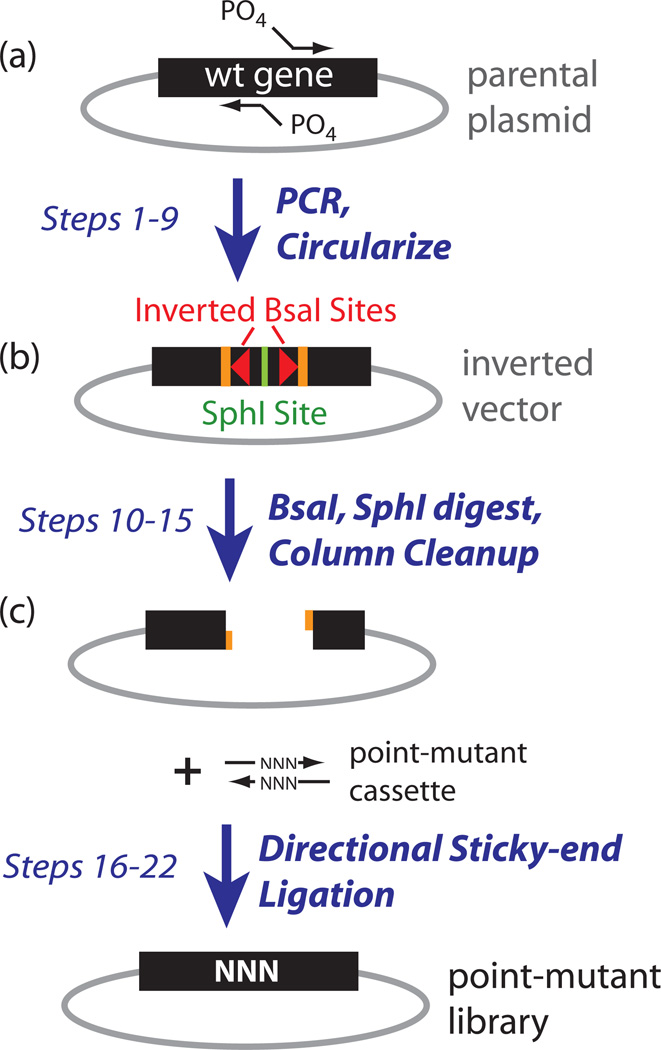

The primary factor that can be manipulated to maximize signal is the relative abundance of each mutant in the starting plasmid library. Ideally, all mutants will be present at a relative abundance well above the noise that comes from mis-reads. We optimized a cassette ligation strategy (Figure 2) that can be applied iteratively and in parallel to generate libraries of point mutants where all variants are present at similar relative abundance. Alternative methods exist to generate point mutant libraries including Quickchange™ mutagenesis and gene synthesis, but in our experience the cassette ligation strategy has resulted in the most efficient and reproducible results.

Figure 2.

Steps to generate plasmid libraries of point mutants. (a) Whole-plasmid PCR to generate inverted BsaI vector. (b) Digestion of this vector to generate directional sticky-ends. (c) Cassette ligation to introduce point mutants.

Design of oligonucleotides for generating vectors with inverted type IIS restriction sites

Oligonucleotides should be designed as primers for whole-plasmid PCR in order to generate vectors with inverted type IIS (i.e. BsaI) restriction sites (Figure 2a and Table 1 – vector for and vector rev). We have used this approach to amplifiable vectors up to 10 kb. The purpose of adding BsaI sites is to generate a unique cloning site. Whole-plasmid primers should have ~20 bases that are complementary to the target plasmid and 5’ extensions to encode restriction sites. These primers anneal to the gene of interest and need to be designed to suit the specific gene. Including additional unique restriction sites in the 5’ extensions (immediately upstream of the BsaI site) can be used to reduce background during subsequent cassette ligations (i.e. SphI in Figure 2). For this strategy to succeed, it is important to have a parental plasmid construct that lacks BsaI sites. We generated a minimal yeast and bacterial shuttle plasmid that we refer to as pRNDM with a KanMX4 marker14 that confers Kanamycin resistance in bacteria, G418 resistance in yeast, and lacks BsaI sites (Figure S1).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides

| Oligo name |

Oligo sequence (5’–3’) | Key features | Modifications required |

Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vector for | ggtggtggtgcatgcggtctcaATTACTCAGTTGATGAGTTT | capitals represent nt complementary to plasmid sequence, bold represent Bsa I overhangs, and italics indicate Bsa I restriction site. | 5’ phosphorylation (Step 1) | Used with ‘Vector rev’ for whole plasmid PCR (Steps 1–9) |

| Vector rev | gcagcagcagcatgcggtctcaCATAGTATTCTATTTTTCTC | capitals represent nt complementary to plasmid sequence, bold represent Bsa I overhangs, and italics indicate Bsa I restriction site | 5’ phosphorylation (Step 1) | Used with ‘Vector for’ for whole plasmid PCR (Steps 1–9) |

| Cas for | tatg NNN agt gaa act ttt gaa ttt caa gct gaa | Underlined text represents the 10-codon region of interest. N indicates a mixture of A,C,T,G at the randomized codon. Bold indicates overhangs complementary to Bsa I sites. | Annealled with ‘Cas rev’ and ligated to vector to create a saturation library (Steps 10–22) Need a different primer for each codon to be randomised. | |

| Cas rev | taat ttc agc ttg aaa ttc aaa agt ttc act NNN | Underlined text represents the 10-codon region of interest. N indicates a mixture of A,C,T,G at the randomized codon. Bold indicates overhangs complementary to Bsa I sites. | Annealled with ‘Cas for’ and ligated to vector to create saturation library by ligation (Steps 10–22) Need a different primer for each codon to be randomised. | |

| PCR1a for | AAGACGGTAGGTATTGATTGT | complementary to promoter region of the library version of the gene of interest. This primer is specific to the vector. | Used with ‘PCR1a rev’ to amplify library version of gene of interest (Step 43) | |

| PCR1a rev | GGGACCTAGACTTCAGGTTGTC | complementary to the 3’ UTR region of the library version of the gene of interest. This primer is specific to the vector. | Used with ‘PCR1a for’ to amplify library version of gene of interest (Step 43) | |

| PCR1b for | gggaccaccacctccgacACACCCCAATCATGTTGCAG | capitals indicate nt complementary to template. The MmeI site is in bold. | Used with ‘PCR1b rev’ to amplify randomized region. Designed to add an upstream MmeI site to the amplicon (Step 44) | |

| PCR1b rev | N25-GATAAAGACATTAATGGTTG | capitals indicate nt complementary to template. N25 indicates 25nt binding site for 3’ deep sequencing primer - check with sequencing provider for current recommendations. | Used with ‘PCR 1b for’ to amplify randomized region. Designed to add downstream primer binding site to amplicon for deep sequencing (Steps X-Y) | |

| Adapt for | N25-ACGTag | capitals indicate a barcode and N25 indicates binding site for 5’ deep sequencing primer –check with sequencing provider for current recommendations. Lowercase nt are complementary to MmeI site. | Annealled with ‘Adapt rev’ and ligated to MmeI-digested PCR1b product to add a barcode and an upstream (5’) primer binding site for deep sequencing. (Step 46) A different primer with unique barcode is needed for each sequencing sample. | |

| Adapt rev | ACGT-N25 | Capitals indicate a barcode and N25 indicates binding site for 5’ deep sequencing primer – check with sequencing provider for current recommendations. | Annealled with ‘Adapt for’ and ligated to MmeI-digested PCR1b product to add a barcode and an upstream primer binding site for deep sequencing (Step 46) A different primer with unique barcode is needed for each sequencing sample. |

Design of oligonucleotides cassettes with individual codons randomized

Oligonucleotides for the cassette mutagenesis step (Cas for and Cas rev in Table 1) should have cohesive ends that are complementary to the BsaI 5’ overhangs in the vector. These oligos will be annealed to each other to form a ds cassette – they are not used for priming amplification/mutagenesis. For each amino acid position that you would like to randomize, design a cassette with a degenerate codon (i.e., NNN) on both strands. We have obtained consistent results using cassettes where each oligonucleotide is 40 bases in length (30 bases for the 10 amino acid region, 3 bases on either side of this region that improve ligation efficiency for the randomization of edge positions, and the 4-base 5’ overhangs).

Design of oligonucleotides to amplify the library gene

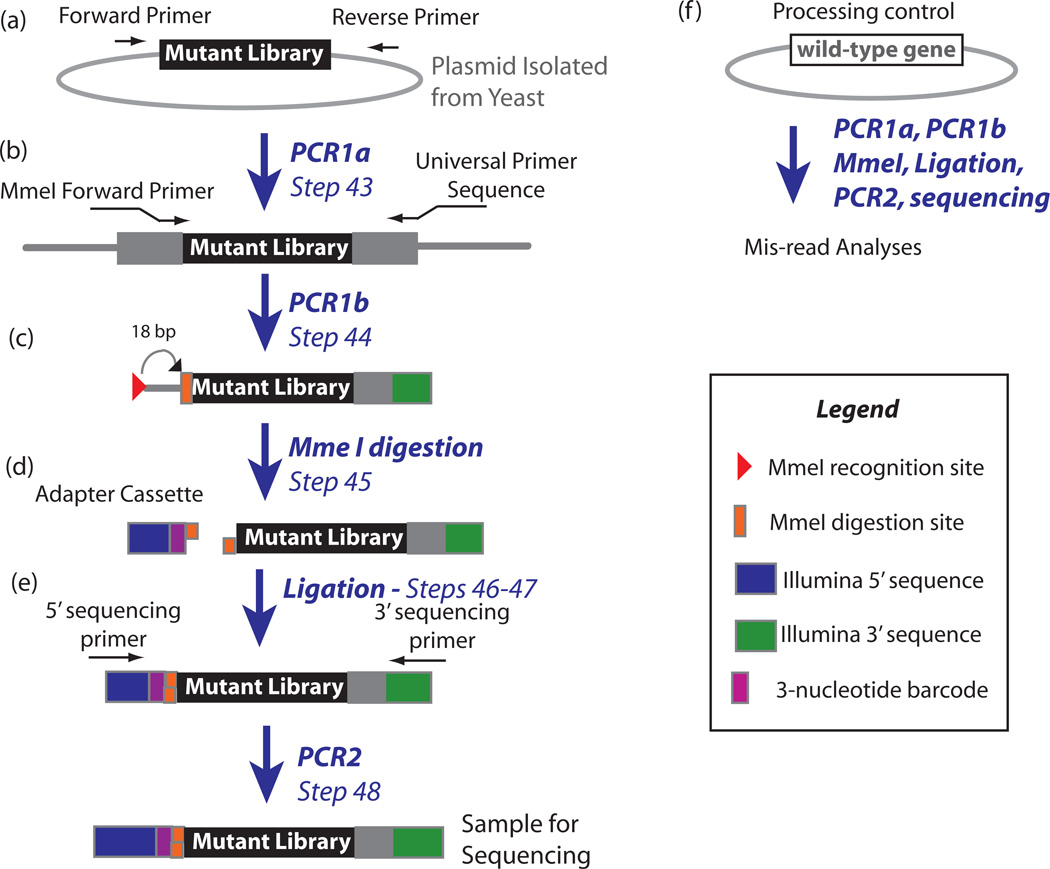

PCR1a primers (Figure 3a, PCR1a for and PCR1a rev in Table 1) should be designed to specifically amplify the library version of the gene of interest (and not the conditional genomic copy also present in cells). The optimal size range of the amplicon is 250 bases. Standard primer design approaches should be used. PCR1a primers should be 18–22 bases and anneal uniquely to the library plasmid (i.e. to unique regions upstream and downstream of the gene of interest). These are primers are gene-specific.

Figure 3.

Steps to prepare DNA for deep sequencing. (a) PCR amplify mutant library using primers specific to plasmid library. (b) Perform second PCR step to add MmeI site to 5’ end and Illumina universal primer sequence to 3’ end. (c) Perform MmeI digestion to create sticky end adjacent to randomized region of the mutant library. (d) Ligate an adapter to the 5’ end containing a barcode. (e) PCR with universal deep sequencing primers. (f) Parallel analyses of a wild-type plasmid provide information on mis-reads.

Design of oligonucleotides to focus sequencing on the randomized region

PCR1b primers (Figure 3b) should be designed to: amplify the randomized region; add an upstream MmeI site (the purpose of the MmeI site is to provide a site for adapter ligation); and add a downstream Illumina sequencing site. The MmeI PCR1b primer (PCR1b for in Table1) should have 20 bases of complementarity to the region immediately upstream from the randomized region (gene specific) and a 5’ extension encoding a restriction site for MmeI. The downstream PCR1b primer (PCR1b rev in Table 1) should have 18–22 bases of complementarity that target binding 200 bases downstream of the randomized region (in order to generate a 200 base amplicon) and a 5’ extension of 25 bases complementary to Illumina sequencing primers.

Design of barcoded adapter oligonucleotide cassette

Oligonucleotides should be designed that when annealed form a double stranded adapter. This adapter cassette should have a double stranded region including 25 bases complementary to Illumina sequencing primers and a barcode of 3–4 bases followed by a two-base single-stranded 3’ overhang complementary to the overhang created by MmeI digestion of the PCR1b PCR product (Figure 3d). Care should be taken in designing barcodes such that all samples in a sequencing reaction can be uniquely identified. A single sequencing sample represents uniquely barcoded timepoint samples for a library of 10 randomized codons, as single-codon libraries are pooled prior to analysis. Ideally, each barcode will differ from all other barcodes at multiple positions to minimize the potential for mis-reads to cause barcode switching. With Illumina sequencing, the base composition at each position in the sequencing library is an important parameter because it impacts the ability to distinguish the position of individual clusters. For this reason, it is valuable to blend samples such that each position in the sequencing mix, including the barcode region, has a broad distribution of bases. This challenge can also be mitigated by further blending with other sequencing samples or generating a lower density of clusters during sequencing and should be discussed with your sequencing provider.

Conditional strain

It is important to have a conditional strain that grows robustly on its own under permissive conditions, and whose growth rapidly slows or stalls in non-permissive conditions unless provided with a rescue copy of the gene of interest. In our proof-of-principle studies1, we utilized a temperature sensitive Hsp90 strain. This strain grows robustly at 25 °C, which allowed all possible point mutants in our library to be transformed into cells and propagated under this condition. This strain rapidly stalls growth at moderately elevated temperature (36 °C), which was used to synchronize growth competition dependent on the function of the library version. Before starting competition experiments with libraries, it is important to identify appropriate permissive and non-permissive conditions. A wild-type rescue plasmid and a null rescue plasmid can be used to determine these conditions. Ideally, you want the permissive condition to support equivalent growth rates for strains harboring either the wild-type or the null rescue plasmid. For the non-permissive condition, cells harboring the wild-type rescue plasmid should grow robustly (i.e. similar to the parental strain), while cells harboring the null plasmid should stall in growth.

Sources of noise

The primary cause of noise is mis-reads that can be caused by either PCR steps in processing samples, or in the sequencing reaction itself. We have found it extremely useful to include internal controls to assess the mis-read noise in each EMPIRIC experiment and sequencing run (these controls are described in the Procedure). In our experience, ~90% of Illumina sequencing runs have resulted in data quality sufficient to accurately assess the relative abundance of all point mutants in EMPIRIC experiments. The careful generation of point mutant libraries causes the majority of mis-reads to appear as double-mutants that are readily filtered out of datasets, dramatically reducing noise in subsequent analyses.

Genetic background is another potential source of noise that is important to consider in EMPIRIC experiments. In order to control for genetic background, we design entire experiments such that all required libraries are transformed into the same batch of yeast, thus minimizing potential secondary genetic differences. If secondary mutations of strong benefit sweep through a mutant population, it will cause a bi-phasic trajectory in the fitness data that can be readily identified. In this case only time-points prior to this sweep should be analyzed. If appropriate, secondary mutations of strong benefit can be minimized by pre-adapting the parental strain to the desired environmental conditions. We have also found that eliminating the 2µ plasmid that is endogenous in most yeast strains15 can reduce the frequency of secondary adaptive genetic changes.

Materials

REAGENTS

CRITICAL: All media and reagents are prepared by standard methods16, and are stored as recommended by the manufacturers. All enzymes are stored at −20 °C. SAM and chemically competent bacteria are stored at −80 °C. Unless otherwise noted, all reagents are stored at room temperature.

A conditional yeast strain (i.e. a temperature sensitive or shutoff strain) whose growth can be rescued by a plasmid-borne copy of the gene of interest. Conditional yeast strains can be generated de novo, or located in previously published work and requested.

A starting plasmid to generate libraries that does not contain sites for the type IIS endonuclease that you plan to use for the cassette ligation strategy, such as pRNDM (Figure S1). The pRNDM plasmid will be provided on request.

T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs, cat. no.M0202)

T4 DNA Ligase Buffer 10× (New England Biolabs, cat. no. B0202S)

T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (New England Biolabs, cat. no. M0201)

Deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs; 10 mM each nucleotide; New England Biolabs, cat. no. N0447)

DpnI restriction endonuclease (New England Biolabs, cat. no. R0176)

Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs, cat. no. M0273)

-

Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, cat. no. M0530S)

▲CRITICAL – a high-fidelity polymerase should be used for amplification products intended for use in downstream deep-sequencing to limit PCR errors.

BsaI restriction endonuclease (New England Biolabs, cat. no.R0535)

SphI restriction endonuclease (New Englan Biolabs, cat. no.R0182)

MmeI restriction endonuclease (New England Biolabs, cat. no. R0637L)

S-adenosyl methionine (SAM; New England Biolabs, cat. no. B9003S)

NEB3 buffer (10× with 100× BSA; New England Biolabs, cat. no.B7003)

NEB4 buffer (10×; New England Biolabs, cat. no. B7004S)

Agarose, PCR grade (Fisher Bioreagents, cat. no. 9012-36-6)

-

Ethidium bromide (Sigma, cat. no. E1510)

! CAUTION Ethidium bromide is toxic and a DNA mutagen; handle properly and avoid contact using appropriate Personal Protective Equipment.

SYBR Green I (10000×; Invitrogen, cat. no. S-7563)

Tris Base (Fisher Bioreagents, cat. no. BP152-500)

Acetic acid, glacial (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. A38-500)

Bromophenol Blue (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. B0126)

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. E6758)

DNA ladder – 1 KB (New England Biolabs, cat. no. N3232)

DNA ladder – 100 BP(New England Biolabs, cat. no. N3231)

Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit (Zymoresearch, cat. no. D4001)

ZR Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Zymoresearch, cat. no. D4015)

OmniMax competent E. coli strain (Invitrogen, cat. no. C854003)

Kanamycin-A monosulfate (or bacterial antibiotic matching vector marker)(Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. K4000)

Ampicillin sodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. A9518-100G)

G418 disulfate salt (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. A1720)

Polyethylene Glycol 3350 (PEG 3350; Hampton Research cat. no. HR2-591)

Lithium acetate dihydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. L4158)

Salmon Sperm DNA (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. D1626)

Yeast nitrogenous base without Amino Acids (VWR, cat. no. 61000-200)

Ammonium Sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. A5132)

Sodium Chloride (Fisher Bioreagents, cat. no. 5271-3)

Zymolyase (Zymoresearch, cat. No E1004)

Bacto- Tryptone (Becton Dickison, cat. no. 211705)

Bacto- Peptone (Becton Dickison, cat. no. 211677)

Bacto- Yeast Extract (Becton Dickison, cat. no. 212750)

Bacto- Agar (Becton Dickison, cat. no. 214010)

Adenine Hemisulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. A9126-100g)

L-Aspartic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. A8949)

L-Arginine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. A5006)

L-Valine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. V0513)

L-Glutamic Acid (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. G1251)

L-Serine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. S4311)

L-Threonine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. T8625)

L-Isoleucine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. I2752)

L-Phenylalanine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. P2126)

L-Tyrosine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. T8566)

L-Histidine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. H8000)

L-Methionine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. M5308)

L-Leucine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. L8000)

L-Lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. L5501)

Oligonucleotides (IDT DNA Technologies) see Table 1 for oligonucleotides used to study a 10 amino acid sequence of Hsp90 (DNA sequence: 5’ GCTAGTGAAACTTTTGAATTTCAAGCTGAA 3’) in pRNDM

Custom bio-informatics software (available from www.labs.umassmed.edu\Bolonlab).

EQUIPMENT

Incubator set to 37°C (Fisher Scientific, Model 655D)

1.7 mL microcentrifuge tubes (Sorenson Biosciences, cat. no. 16070)

Microcentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Microfuge 18)

UV trans-illuminator (UVP, Model M-15)

Razor blades (VWR, cat. no. 55411-050)

Heatblock set to 42 °C (VWR, cat. no. 13259-030)

Shaking incubator (Infors HT, Multitron Standard)

Spectrophotometer capable of measuring absorbance at 600 nm. (Cary, 50 UV)

Thermocycler for PCR (Applied Biosystems, cat. no. 2720)

−80 °C freezer for storage of yeast pellets (Sanyo, cat. no. MDF-U76VC)

Heat block set at 50 °C (VWR, cat. no. 13259-030)

Autoclave (Brinkmann, cat. no. 023210100)

100×15 mm Petri dishes (VWR, cat. no. 25384-088)

125ml flasks (Corning, cat. no. 29136-048)

BD Falcon 14ml culture tubes (BD Falcon cat. no.352057)

Tabletop centrifuge capable of spinning 14ml culture tubes at 3000g (Sorvall, Legend RT)

Electrophoresis power supply (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. FB300Q)

Agaraose gel system (Hoefer, cat. no. HE33)

Nanodrop spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Nanodrop2000)

REAGENT SETUP

PEG 3350 50% (w/v) solution – dissolve 50 grams of solid powder in water to a final volume of 100 ml. Sterilize by vacuum filtration and store at room temperature.

Lithium acetate 1.0 M solution – dissolve 102 grams into water to a final volume of 1L. Sterilize by vacuum filtration and store at room temperature.

Salmon Sperm DNA, 10 mg/ml solution – dissolve 200 mg of lyophilized powder in 20 mL of water. Make 1.0 ml aliquots, place in boiling water bath for 10 minutes, place on ice for 10 minutes, and store at −20 °C.

G418 antibiotic, 250× solution – dissolve 500 mg of G418 in water to a final volume of 10 mL. Filter sterilize and store at −20 °C.

Kanamycin stock solution – dissolve 250 mg of Kanamycin in 10 mL of water and filter sterilize. Store at −20 °C for up to 1 year.

LB media -dissolve 10 g of Trytpone, 5 g of Yeast Extract, and 5 g of Sodium Chloride in 1 L of water and autoclave. Store at room temperature.

LB+Kanamycin media – Add 1.2 mL of Kanamycin stock solution to 1L of LB and store at 4 °C for up to 1 week.

LB+Kanamycin plates - prepare 1 L of LB, add 15 g of Bacto agar and autoclave. Cool to 60 °C and add 1.2 mL of Kanamycin stock solution. Pour into petri dishes and cool to solidify. Store at 4 °C for up to 2 months.

40% Glucose – dissolve 400 g of Glucose in water to a final volume of 1 L. Filter sterilize and store at room temperature for up to 1 year.

YPDA media – dissolve 10 g of Yeast Extract, 20 g Bacto Peptone, and 0.1 g of Adenine Hemisulphate in 1 L of water. Autoclave and allow to cool to room temperature. Add 50 mL of 40% glucose. Store at 4 °C for up to 1 week.

G418 stock solution – dissolve 500 mg of G418 in water to a final volume of 10 mL. Filter sterilize and store at −20 °C for up to 1 year.

YPDA+G418 media – add 4 mL of G418 stock solution to 1 L of YPDA. Store at 4 °C for up to one week.

2X YPDA media – dissolve 20 g of Yeast Extract, 40 g Peptone, and 0.1 g of Adenine Hemisulphate in 1 L of water. Autoclave and allow to cool to room temperature. Add 50 mL of 40% glucose. Store at 4 °C for up to 1 week.

Procedure

Generating Plasmid Libraries of Point Mutants TIMING about 1 week

-

1Add 5’ phosphates to each whole plasmid PCR primer (e.g. ‘Vector for’ and ‘Vector rev’ primers in Table 1): Dissolve primers in water to 100 µM and setup an individual phosphorylation reaction for each primer as tabulated below. Incubate for 30 minutes at 37 °C. No further purification is necessary and the primers can be stored at −20 for up to 1 year.

Component Amount per reaction (µL) Final Water 41 T4 DNA Ligase Buffer (10×) 5 1× Primer (100 µM) e.g. ‘Vector for’ or ‘vector rev’ in Table 1 3 6 µM T4 Polynucleotide kinase (10 U µL−1) 1 10 U -

2Perform whole-plasmid PCR: Setup a PCR reaction with the following components.

Component Amount per reaction (µL) Final Water 27 Phusion HF buffer (5×) 10 1× Phosphorylated Primers (6 µM) e.g. ‘Vector for’ or ‘vector rev’ in Table 1 5 of each 0.6 µM dNTP mix (10 µM) 1 0.2 µM Plasmid template (200 ng µL−1) 1 200 ng Phusion polymerase (2 U µL−1) 1 2 U -

3Run the samples in thermocycler with the following conditions:

Cycle number Denature Anneal Extend 1 95 °C, 2 min 2–16 95 °C, 30 s 55 °C, 30 s 72 °C, 1 min per kb -

4

When the PCR is finished, cool to room temperature (23 °C) and add 1 µL DpnI restriction endonuclease to degrade the template plasmid. Incubate at 37°C for 1h.

-

5

Run the PCR reaction on an agarose gel, excise the appropriate fragment and purify. We utilize Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit gel purification kits (see Reagents) and follow the manufacturer’s instructions. TROUBLESHOOTING.

-

6Circularize the gel-purified fragment vector by performing a unimolecular blunt-ended ligation with the following components and incubating at room temperature for 1 hour:

Component Amount per reaction (µL) Final Water 4 T4 DNA Ligase Buffer (10×) 1 1× Gel purified PCR product (from step 5) 4 Varies T4 DNA Ligase (400 U µL−1) 1 400 U -

7

Transform the ligation reaction into a cloning strain of E. coli by mixing 100 µL of competent cells with 5 µL of the ligation reaction, incubating on ice for 15 minutes, heat-shock at 42 °C for 45 seconds, cool for one minute on ice, add 1 mL of room temperature LB broth, incubate at 37 °C for 1 hour, spread 100 µL of cells onto LB-Kanamycin plates, and grow at 37 °C for 16 hours.

-

8

Pick two individual colonies and grow each in liquid culture (LB-Kan) for 16 hours at 37 °C.

-

9

Isolate plasmid DNA using a ZR Plasmid Miniprep Kit and Sanger sequence. One or both plasmids usually have the appropriate sequence and can be used in subsequent steps.

-

10

Prepare cassettes containing saturation mutants. Dissolve the forward and reverse oligonucleotides (e.g. ‘Cas for’ and ‘Cas rev’ in Table 1) in water to a final concentration of 100 µM. Combine 50 µL of forward and 50 µL of reverse oligonucleotides so that the final cassette concentration is 50 µM.

-

11

Anneal cassettes by boiling followed by slow cooling: Boil 1 L of water, float 100 µL of the cassettes in boiling water, remove from heat and allow entire water bath to cool naturally to ambient temperature (~1 hr).

-

12

Dilute annealed cassettes to 0.5 µM in water.

-

13

Digest the vector to generate cohesive ends that complementary to the cassettes. Set up a BsaI digest as tabulated below and incubate at 50 C for 2 hours.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Sequential digestion with BsaI followed by a second enzyme that cuts between the BsaI sites (i.e. SphI in Figure 2) reduces undesired ligation products and improves library quality.Component Amount per reaction (µL) Final Plasmid from step 9 (200 ng µL−1) 3 600 ng NEB buffer 3 (10×) 5 1× Bovine Serum Albumin (10 mg/ml – sterile filtered) 0.5 0.1 mg/ml Water 36.5 BsaI enzyme (10 U µL−1) 5 50 U -

14

Allow sample to cool to room temperature. Add 1 µL SphI enzyme and incubate at 37°C for 1 hr.

-

15

Column purify the digested plasmid using a Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit. The small BsaI and SphI fragments will not bind efficiently to silica columns, reducing background ligation products.

-

16Setup a separate ligation reaction for each cassette containing the following reagents and incubate at room temperature for 1 hour.

Component Amount per reaction (µL) Final Digested plasmid from step 15 (~10 nM) 2 ~ 1 nM Annealed cassette from step 12 (0.5 µM) 2 100 nM T4 DNA Ligase buffer (10×) 1 1× Water 4 T4 DNA Ligase (400 U µL−1) 1 400 U -

17

Place tubes from step 16 into an ice bath for five minutes.

-

18

To each tube add 100 µL of chemically competent E. coli. Incubate on ice for 15 minutes.

-

19

Place tubes in 42 °C water bath for 45 seconds, then place back on ice for 1 minute. Add 1 mL of room temperature LB broth and incubate at 37 °C for one hour.

-

20

To analyze transformation efficiency, plate 10 µl of the transformed E. coli onto selective plates e.g LB+Kanamycin. TROUBLESHOOTING.

▲ CRITICAL STEP The library size of a single randomized codon is 64. The probability of sampling each possible library member is related to the number of transformants in this step. A good rule of thumb is to have 10-fold or greater coverage, meaning 640 or more total transformants and at least 6 colonies from the 10 µL plated. This procedure routinely produces 2,000 – 8,000 total transformants.

-

21

Inoculate the remaining 990 µl of recovery mixture from step 20 into a sterile flask containing 10 ml of selective liquid growth media (e.g. LB+Kanamycin) and grow overnight at 37 °C on an orbital shaker at 180 RPM.

-

22

After overnight growth of the cultures, prepare plasmid libraries. Libraries can be readily combined at this step. To prepare a library of 10 different amino acid positions, combine equal volumes of saturated culture for each position and prepare plasmid DNA from this combined culture using a ZR Plasmid Miniprep Kit. We typically prepare a mini-prep from 3 mL of culture and discard the remaining culture. We have found that growing cultures larger than 3 mL from bulk transformations is necessary for consistent yields in DNA preparations.

▲ CRITICAL STEP To assess the quality of the library, it is useful to prepare at least one library with a single randomized codon. Sanger sequencing of this sample should show incorporation of all four nucleotides at the randomized codon and homogeneous sequencing at all other positions.

Generating Libraries of Yeast TIMING about 1 week

-

23

From a frozen stock, streak out the conditional yeast strain to be transformed at least 72 hours prior to transformation. The media used must be permissive to your strain and will vary depending on the conditional strain used. Throughout this protocol we will provide example media based on using a temperature sensitive strain1. This strain can be propagated on YPDA plates at 30 °C.

-

24

Allow individual colonies to grow to between 1–2 mm in diameter. 20 Hours before transformation, inoculate a single yeast colony into 3 mL of appropriate liquid media (e.g. YPDA) Grow cultures overnight on an orbital rotator set at 180 RPM at the appropriate permissive temperature for the conditional strain.

-

25

When overnight cultures reach near-saturation, determine cell density by counting with a hemocytometer. Add 2.5 × 108 cells to a flask containing 50 mL of rich media (e.g., 2× YPDA), which is sufficient for up to 10 transformations. Incubate on an orbital shaker at 180 rpm for at least 2 cell doubling times, which is from 4–8 hours depending on the strain.

-

26

Prepare competent yeast from the cultures using the lithium acetate method17, 18.

▲ CRITICAL STEP It is important to use freshly prepared competent cells in order to achieve efficient transformation.

-

27

Add 1 µg of library plasmid DNA (from step 22) to 360 µL of competent yeast and vortex briefly to mix.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Plasmid transformation into yeast should be performed to maximize independent transformed cells while minimizing the number of cells that acquire more than one plasmid19.

▲ CRITICAL STEP In addition to the transformation of plasmids with point mutant libraries, you should also transform a negative control (vector without the gene of interest, as well as a positive control (vector with a wild-type copy of the gene of interest).These controls enable you to monitor selection pressure in your experiment. When switched to selective conditions, the negative control strain should stop growing and the positive control should continue to grow robustly.

-

28

Incubate while rocking at room temperature for 30 minutes, then transfer to a 42 °C water bath for 30 minutes.

-

29

Pellet cells at 6,000g for 1 minute at room temperature. Discard supernatant and re-suspend cells in 1 mL of permissive media (e.g. YPDA).

▲ CRITICAL STEP For the transformation of G418-resistant plasmids it is important to outgrow yeast under permissive conditions for at least six hours at room temperature prior to exposure to G418 in step 31

-

30

This step can be done overnight. Re-suspend yeast transformation in 5 mL of media lacking G418. Ampicillin can be added to a final concentration of 0.05 µg/ml at this stage and all subsequent yeast growth steps to hinder bacterial contamination. Grow at 25 °C for 6–18 hours to allow transformed cells to develop antibiotic resistance to G418.

-

31

Spread 50 ul of each yeast transformation on a plate containing G418. Incubate plates at 30 °C for 48–72 to hours. A library of single codon variants for a ten amino acid region contains 640 possible variants. Ten-fold coverage or better is desired for sampling and represents 6,400 independent yeast transformants. Typical yeast plasmid transformations yield 20,000 – 100,000 independent transformants.

-

32

Take remaining yeast transformation from step 30 (~4.95 mL) and pellet at 3,000g for 5 minutes at 4 °C, aspirate supernatant and re-suspend in 15 mL of permissive media. Repeat for a total of 5 washes.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Extracellular plasmid will contribute noise in subsequent analyses and should be thoroughly washed away.

-

33

Add washed cells to 50 mL sterile culture medium (e.g. YPDA) with G418 under otherwise permissive conditions.

Bulk Yeast Competitions TIMING about 1 week

-

34

Measure the optical density of the yeast cultures at 600 nm (OD600) immediately after inoculation and record. Measure the OD600 periodically (e.g. every 12 hours) to determine when the culture enters mid-logarithmic growth, usually between 12 and 48 hours. When the culture enters mid-log phase (OD600=0.4–1), dilute as needed into fresh media to maintain an OD600 between 0.1 and 1. Maintain cultures in log growth for a total of at least 48 hours, targeting a final OD600 of 0.8.

-

35

Harvest approximately 20 ml of cells of OD600 = 1.0, and place in a 50ml conical tube. This sample represents your yeast library before selection for mutational function. Adjust the harvest volume relative to the actual measured OD600. For example, if the OD600 is 0.5, harvest 40 ml of cells. Centrifuge harvested cells for 5 minutes at 3,000g at 4 °C. Aspirate off supernatant and wash with 25 mL of water. Centrifuge again, aspirate off supernatant, and store pellet at −80 °C.

-

36

Pellet remaining culture and re-suspend in media conditions that select for the function of the library gene. For example, if you are using a temperature sensitive strain1, transfer the culture to the non-permissive temperature. If you are using a shutoff strain20 with your library constitutively expressed, transfer the culture to shutoff conditions. Record the OD600 every two hours for the initial 12 hour period and then every 8 hours. Harvest samples as described in step 35 every four 3–4 hours for the first 12 hours of growth and then every 8 hours thereafter. Dilute samples to maintain OD600 between 0.05 and 1. Continue growth experiment for about 20 generations of the wild-type control. Growth of the negative control should stall. This time-course has provided useful results for the analysis of essential yeast genes including Hsp90 under multiple growth conditions in our lab. This time-course could be adjusted to account for the desired fitness resolution (i.e. shorter time courses and fewer points would result in less precise fitness measurements, but could be used to distinguish null mutants from viable mutants), as well as for potential gene-specific and condition-specific effects.

TROUBLESHOOTING.

▲ CRITICAL STEP – Record all dilutions to accurately generate a growth curve for library, positive and negative control cells. During dilutions, always pass at least 1 × 107 cells to avoid population bottlenecks.

Preparation of DNA from yeast competitions TIMING about 1 week

-

37

Remove yeast pellets from −80 °C freezer and resuspend in 200 µL of P1 buffer containing RNAse.

-

38

Add 5 ul of zymolyase (150 units per mL) to each resuspended pellet and mix by pipetting. Incubate for 1.5 hours at 37 °C.

-

39

Add 300 ul of P2 buffer and invert 10 times to mix. Incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes.

-

40

Add 420 ul P3 buffer. Invert 10 times to mix.

-

41

Centrifuge for 10 minutes at 18,000g at room temperature.

-

42

Purify DNA from supernatant using a silica column.

-

43PCR amplify using primers specific to the library version of the gene (e.g. ‘PCR1a for’ and ‘PCR1a rev’, Table 1) and purify the resulting product on an agarose gel. Performing this step reduces sequencing of the conditional copy of the gene (i.e. the temperature sensitive or shutoff version), which would otherwise be the dominant read in the sequencing reaction. This can be accomplished using primers targeted to regions upstream and downstream of the coding region that are unique to the library plasmid.

Component Amount per reaction (µL) Final Water 27 Phusion HF buffer (5×) 10 1× Primers (50 µM) e.g. ‘PCR1a for’ and ‘PCR1a rev’ in Table 1 0.5 of each 0.5 µM dNTP mix (10 µM) 1 0.2 µM Template DNA (from step 42) 10 Varies Phusion polymerase (2 U µL−1) 1 2 U Cycle number Denature Anneal Extend 1 95 °C, 2 min 2 to ~21 95 °C, 30 s 55 °C, 30 s 72 °C, 1 min per kb ▲ CRITICAL STEP – Using a high-fidelity polymerase and minimizing PCR cycles limits errors that contribute noise to subsequent fitness analyses. Typically 18–22 cycles are sufficient to produce a strong PCR product at this stage, and care should be taken to avoid un-necessary PCR cycles throughout the rest of the protocol. To assess processing errors, include a control sample at this stage consisting of a plasmid of homogeneous sequence. For example, use a plasmid encoding the wild-type gene and perform the same PCR steps and manipulations. Using this control, we have found that the number of mis-reads from the entire processing procedure is compatible with reproducible fitness measurements that correlate with traditional fitness analyses of individual mutants1.

-

44PCR to add MmeI restriction site and 3’ Illumina universal primer sequence (Figure 3) and purify the resulting product on a silica column.

Component Amount per reaction (µL) Final Water 27 Phusion HF buffer (5×) 10 1× Primers (50 µM) e.g. ‘PCR1b for’ and PCR1b rev’ in Table 1 0.5 of each 0.5 µM dNTP mix (10 µM) 1 0.2 µM Template (PCR product from step 43) 10 varies Phusion polymerase (2 U µL−1) 1 2 U Cycle number Denature Anneal Extend 1 95 °C, 2 min 2 to ~11 95 °C, 30 s 55 °C, 30 s 72 °C, 30 s ▲ CRITICAL STEP – Typically 8–12 cycles are sufficient to produce a strong PCR product at this stage.

-

45Digest PCR product from step 44 with MmeI enzyme using the following setup. Incubate at 37 °C for 1 hour, then heat inactivate at 80 °C for 20 minutes.

Component Amount per reaction (µL) Final PCR product (20 ng µL−1, from step 44) 10 200 ng NEB buffer 4 (10×) 2 1× SAM (1 mM) 1 50 µM Water 5 MmeI enzyme (2 U µL−1) 2 4 U ▲ CRITICAL STEP – Freshly prepare 1 mM SAM in water by dilution of the concentrated stock solution. SAM is unstable in water and the 1 mM solution should be used immediately.

-

46

Ligate adapters containing a binding site for 5’ universal deep sequencing primers and a barcode to the MmeI digested DNA. Mix the components tabulated below and incubate at room temperature for 30 minutes, then heat inactivate at 65 °C for 10 minutes.

▲ CRITICAL STEP – Use adapters whose overhangs are complementary to the overhangs from the MmeI digestion in step 45. If planning to pool samples for sequencing, use barcodes that differ by at least two nucleotides from all other barcodes to minimize barcode switching from mis-reads.Component Amount per reaction (µL) Final MmeI digested DNA (10 ng µL−1, from step 45) 15 150 ng T4 DNA Ligase buffer (10×) 2 1× Adapter (6 µM) e.g. ‘Adapter for’ and ‘Adapter rev’ in Table 1 2 600 nM T4 DNA Ligase (400 U µL−1) 1 400 U -

47

Separate the ligation reaction on an agarose gel, excise the ligated band and purify on a silica column.

▲ CRITICAL STEP – At this step, the goal is to deplete adapter dimers from your sample. These dimers will readily separate from the product of interest. However, the MmeI digestion and adapter ligation reactions typically go to about 70% completion which produces a complex banding pattern. However, neither the undigested nor unligated products PCR amplify in subsequent steps.

-

48PCR the gel purified products (from step 47) with Illumina universal primers. Separate the PCR product on an agarose gel, excise the appropriate band, column purify. This sample is ready for deep sequencing.

Component Amount per reaction (µL) Final Water 26 Phusion HF buffer (5×) 10 1× Illumina Universal primers (10 µM) 1 of each 0.2 µM dNTP mix (10 µM) 1 0.2 µM Template (from step 47) 10 varies Phusion polymerase (2 U µL−1) 1 2 U Cycle number Denature Anneal Extend 1 95 °C, 2 min 2 to ~11 95 °C, 30 s 55 °C, 30 s 72 °C, 30 s ▲ CRITICAL STEP – PCR steps should be minimized. This step typically requires 8–14 cycles of PCR. Samples representing different time-points can be pooled if they are distinctly barcoded and amplify with similar cycles of PCR.

▲ CRITICAL STEP – Mis-reads from deep sequencing are highly variable and should be internally assessed in every run. This can be accomplished by generating a plasmid containing universal deep sequencing primer sites, which can be utilized to generate a sequencing control with minimal PCR steps (about eight) and hence minimal sequence heterogeneity. This sample should be mixed in with timepoint samples at about a 1/100 molar ratio in all analyses. This sample should ideally be distinct from all other samples in the sequencing reaction.

Analyzing the Sequencing Data TIMING about 1 day

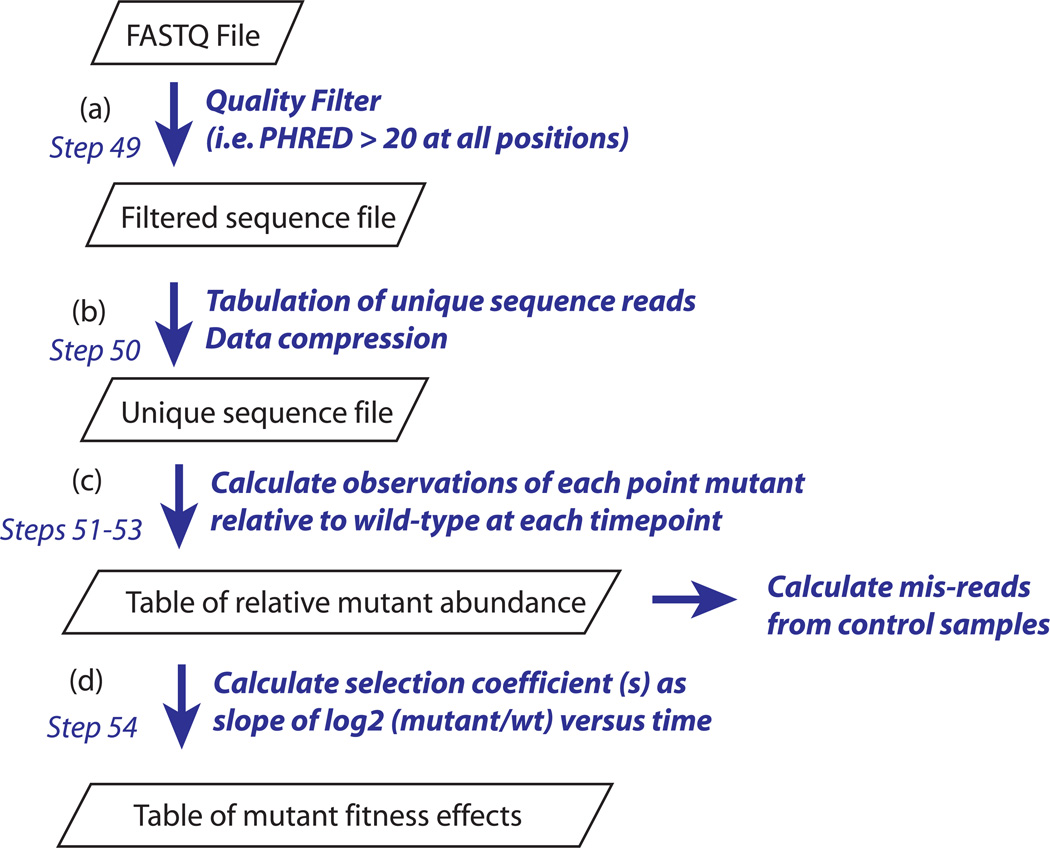

CRITICAL: All data analysis is performed as outlined (Figure 4) with custom programs (www.labs.umassmed.edu/Bolonlab). Knowledge of linux, perl, and deep-sequencing are required for the analysis steps.

-

49

Perform quality filtering. Using the FASTQ file (the output file from sequence analysis) as input, check the quality score at all nucleotide positions for each read21. Define a threshold (we frequently use PHRED>20, which corresponds to >99% confidence). Create a new output file that contains sequences for which all basecalls pass this threshold.

-

50

Enumerate the unique sequence reads and how often they were observed. This serves to compress the data dramatically and speeds subsequent analyses.

-

51

Generate an input mask file that describes the experiment including: the correspondence between barcode sequence and time-point; and the wild-type sequence.

-

52

Tabulate the number of reads of each possible single-codon variant at each timepoint. Importantly, this step removes all sequences that contain apparent codon changes at two or more positions. This filtering step removes many mis-read events and improves signal to noise. TROUBLESHOOTING.

▲ CRITICAL STEP – Analyze the internal sequencing and processing controls (described in step 44 and 49). Sequencing and PCR/processing errors will appear as mutations in these samples. We have typically observed processing mis-read rates of ~2 in 1,000 base calls. Taking into account that ~90% of mis-reads will be filtered out as apparent double mutants in library samples, this translates to an effective noise per base called of ~2 in 10,000. With this mis-read rate, the vast majority of 36-base reads (~0.999836 = 99.2%) will be accurate over each base. Because the remaining mis-read noise is distributed over multiple mutants, the average signal to noise ratio for each mutant is ~100:1. The non-linear relationship between per base mis-read rates and mutant noise, makes it valuable to have low mis-read noise. If the processing per base mis-read rate is above 1 in 100 we typically perform a second sequencing analysis. By having an independent control for processing (including all PCR steps) and sequencing (without most PCR steps), it is possible to determine where problems occurred and go back to the appropriate step: re-doing either processing and/or sequencing. Of note, mis-read errors are not random and can vary from run to run. Having internal controls should enable improved error-handling in future work. In addition, mis-read errors are dependent on sequencing platform. We have utilized Illumina sequencing in all of our analyses to date.

-

53

For each possible single-codon variant, calculate the mutant to wild-type ratio at each timepoint. Of note, the abundance of wild-type sequence reads in our plasmid libraries is typically between 1–4%, about 10-fold higher than each point mutant because it is generated independently at each amino acid position. If each codon randomization is completely random, the wild-type sequence would be present at 1.5% (1/64). This provides improved counting accuracy of the wild-type sequence which is used as the reference for calculating the relative abundance of all point mutants.

-

54

Determine the slope of log2(mutant/wt) versus time in wild-type generations. This is a direct measure of fitness called the selection coefficient (s). For neutral mutations, s=0; while deleterious mutations have s<0; and beneficial mutants s>0. Of note, other groups have developed software for analyzing more complex mutant libraries that include multiple mutations22, 23.

Figure 4.

Analysis pipeline for measuring fitness effects of mutations from deep sequencing data. (a) Sequences that pass quality filtering at all positions in the read are stored in a sequence only file. (b) The occurrence of each unique sequence read is summed resulting in a dramatic compression of file size. (c) At each time-point, calculate the relative abundance of each point-mutant in the library. For the control samples, calculate the mis-read rate per base (d) Calculate the fitness of each point mutant based on its change in relative abundance over time.

Troubleshooting

Troubleshooting advice is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Troubleshooting

| Step | Problem | Possible reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Multiple bands | Non-specific primer binding | Increase annealing temperature and/or identify appropriate band by running single-cut plasmid in adjacent lane. |

| 20 | Poor transformation efficiency | Ratio of cassette to vector, or mismatched overhangs. | With phosphorylated vector overhangs and non-phosphorylated cassette overhangs a molar ratio of 50 cassette to 1 vector works well. Occassionally (< 5%) BsaI may cut non-canonically – in this case make a new vector with the BsaI sites moved by 1 nucleotide. |

| 34 | Yeast with negative control plasmid do not halt growing in selective conditions. | Yeast strain contains another copy of the gene, or the gene is not essential. | Re-check or re-make conditional strain. |

| 52 | High noise level from sequencing misreads | Poor quality filtering and/or poor sequencing data. | Re-run the analysis with a more stringent quality cutoff or re-sequence. |

Timing

Steps 1–22, Generating plasmid libraries of point mutants: about 1 week

Steps 23–33, Generating libraries of yeast: about 1 week

Steps 34–36, Bulk yeast competitions: about 1 week

Steps 37–48, Preparation of DNA from yeast competitions: about 1 week

Steps 49–54, Analyzing the sequencing data: about 1 day

Anticipated Results

Generating Plasmid Libraries of Point Mutants

The cassette ligation strategy generally produces 2,000–8,000 transformants. Background transformants (from ligations without any insert cassette) can vary depending on the overhangs left after BsaI digestion. The perfect match between the cassette and vector overhangs usually outcompetes background vector self-ligation. For this reason control transformants (from ligations performed without any insert) do not necessarily indicate a problem. Sanger sequencing of an individually randomized codon library is required to assess quality. If the Sanger chromatogram shows all four bases at randomized positions and homogeneous sequence before and after, then the library is appropriate for further use.

Generating Libraries of Yeast and Bulk Competitions

Plasmid transformations into yeast generally produce 20,000–100,000 independent transformants. Upon transfer to conditions that select for mutant function, growth of library cultures typically slow briefly compared to the growth of the positive control culture (because the average mutation in the library is deleterious relative to wild-type). Growth of the negative control culture should plateau.

Preparation of DNA for Sequencing

All samples should amplify by PCR, digest, and ligate to adapters with similar efficiency.

Analyzing the Sequencing Data

The quality of deep-sequencing data varies dramatically from run to run. Internal sequencing and processing controls should be included in every sequencing sample. If necessary, quality filtering should be adjusted so that the internally determined mis-call rate is well below the signal (abundance of mutants in the library). Within libraries: internal positive controls (i.e., silent mutations) should have near-neutral fitness effects (s≈0); internal negative controls (i.e., stop codons) should have null-like fitness (s≈−1). Because mutants with null-like fitness rapidly decrease in abundance, they can only be observed in early time-points. The switch to selective conditions during these early time-points is not perfectly synchronized across all cells in the culture (i.e., in a shutoff experiment variations in initial protein levels result in variation in shutoff timing in individual cells). This can result in apparent selection coefficients of null mutants that are greater than −1 (typically < −0.5 though). True nulls (i.e., internal stop codons) can be used to define a range of apparent fitness measurements that correspond to null fitness. Mutants that support yeast growth persist in the culture beyond the point where selection synchronization impacts fitness analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM083038) and the American Cancer Society (RSG-08-17301-GMC) to D.N.A.B.

Footnotes

Author Contribution Statement

R.H., B.R., L.J., and D.N.A.B all contributed to the development and optimization of the protocol and writing the article. The initial draft about generating mutant libraries was prepared by R.H, growth competitions by B.R., preparing samples for deep sequencing by B.R. and L.J., and processing sequencing data by D.N.A.B. D.N.A.B supervised the work and prepared the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests Statement.

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Hietpas RT, Jensen JD, Bolon DN. Experimental illumination of a fitness landscape. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7896–7901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016024108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pool JE, Hellmann I, Jensen JD, Nielsen R. Population genetic inference from genomic sequence variation. Genome Res. 2010;20:291–300. doi: 10.1101/gr.079509.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen JD, Wong A, Aquadro CF. Approaches for identifying targets of positive selection. Trends Genet. 2007;23:568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hegreness M, Shoresh N, Hartl D, Kishony R. An equivalence principle for the incorporation of favorable mutations in asexual populations. Science. 2006;311:1615–1617. doi: 10.1126/science.1122469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lind PA, Berg OG, Andersson DI. Mutational robustness of ribosomal protein genes. Science. 2010;330:825–827. doi: 10.1126/science.1194617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith JM, Haigh J. The hitch-hiking effect of a favourable gene. Genet Res. 1974;23:23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giaever G, et al. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature. 2002;418:387–391. doi: 10.1038/nature00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinreich DM, Delaney NF, Depristo MA, Hartl DL. Darwinian evolution can follow only very few mutational paths to fitter proteins. Science. 2006;312:111–114. doi: 10.1126/science.1123539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenski RE. Quantifying fitness and gene stability in microorganisms. Biotechnology. 1991;15:173–192. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-409-90199-3.50015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham BC, Wells JA. High-resolution epitope mapping of hGH-receptor interactions by alanine-scanning mutagenesis. Science. 1989;244:1081–1085. doi: 10.1126/science.2471267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fowler DM, et al. High-resolution mapping of protein sequence-function relationships. Nat Methods. 2010;7:741–746. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitt JN, Ferre-D'Amare AR. Rapid construction of empirical RNA fitness landscapes. Science. 2010;330:376–379. doi: 10.1126/science.1192001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ernst A, et al. Coevolution of PDZ domain-ligand interactions analyzed by high-throughput phage display and deep sequencing. Mol Biosyst. 2010;6:1782–1790. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00061b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wach A, Brachat A, Pohlmann R, Philippsen P. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:1793–1808. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsalik EL, Gartenberg MR. Curing Saccharomyces cerevisiae of the 2 micron plasmid by targeted DNA damage. Yeast. 1998;14:847–852. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980630)14:9<847::AID-YEA285>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guthrie C, Fink GR. Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular and Cell Biology. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gietz RD, Schiestl RH, Willems AR, Woods RA. Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast. 1995;11:355–360. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gietz RD, Schiestl RH. Large-scale high-efficiency yeast transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:38–41. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scanlon TC, Gray EC, Griswold KE. Quantifying and resolving multiple vector transformants in S. cerevisiae plasmid libraries. BMC Biotechnol. 2009;9:95. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-9-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston M, Davis RW. Sequences that regulate the divergent GAL1–GAL10 promoter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:1440–1448. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.8.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cock PJ, Fields CJ, Goto N, Heuer ML, Rice PM. The Sanger FASTQ file format for sequences with quality scores, and the Solexa/Illumina FASTQ variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;38:1767–1771. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fowler DM, Araya CL, Gerard W, Fields S. Enrich: software for analysis of protein function by enrichment and depletion of variants. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:3430–3431. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pitt JN, Rajapakse I, Ferre-D'Amare AR. SEWAL: an open-source platform for next-generation sequence analysis and visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7908–7915. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.