Abstract

Background

Urban minority populations experience increased rates of obesity and increased asthma prevalence and severity.

Objective

We sought to determine whether obesity, as measured by body mass index (BMI), was associated with asthma quality of life or asthma-related emergency department (ED)/urgent care utilization in an urban, community-based sample of adults.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional analysis of 352 adult subjects (age 30.9±6.1, 77.8% females, FEV1%pred=87.0%±18.5) with physician diagnosed asthma from a community-based Chicago cohort. Outcome variables included the Juniper Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) scores and health care utilization in the previous 12 months. Bivariate tests were used as appropriate to assess the relationship between BMI or obesity status and asthma outcome variables. Multivariate regression analyses were performed to predict asthma outcomes, controlling for demographics, income, depression score, and beta-agonist use.

Results

191 (54.3%) adults were obese (BMI>30 kg/m2). Participants with a higher BMI were older (p=0.008), African American (p<0.001), female (p=0.002), or from lower income households (p=0.002). BMI was inversely related to overall AQLQ scores (r =−0.174, p=0.001) as well as to individual domains. In multivariate models, BMI remained an independent predictor of AQLQ. Obese participants were more likely to have received ED/urgent care for asthma than non-obese subjects (OR=1.8, p=0.036).

Conclusions

In a community-based sample of urban asthmatic adults, obesity was related to worse asthma-specific quality of life and increased ED/urgent care utilization. However, compared to other variables measured such as depression, the contribution of obesity to lower AQLQ scores was relatively modest.

Keywords: Asthma, obesity, urban, healthcare disparities, health outcomes

INTRODUCTION

It is well established that urban minority populations have a higher prevalence of asthma with a greater degree of morbidity and mortality. (1–3) An increasing body of literature suggests those populations are also more likely to be obese. (4) Multiple publications have described an association between asthma and obesity. (5–8). Antecedent obesity is associated with an increased annual odds of a new diagnosis of asthma, and, in weight loss cohort studies, an improvement in asthma outcomes has been reported to result from weight loss. (9–11). Obesity, as measured by body mass index (BMI), has been associated in many, but not all studies, with worse asthma quality of life and increased asthma severity. (12–14). In a review of those published studies, participants were generally recruited from clinics and were not urban community-based populations as described in this report (15).

The etiologic relationships linking asthma and obesity remain largely undetermined. In order to show an etiologic effect, the correlative relationship should be strong, consistent, plausible and temporally related. To the latter point, there are reports of temporal relationship provided by the weight loss cohorts. As for the relationship being strong and consistent between asthma and obesity, the relative risk of asthma has ranged from 1.0 to 3.0 in both prospective cohort and cross-sectional human studies (5–7). In some studies, it has been reported that the association between obesity and asthma occurs only in women or only in men (7, 16). Overall, then, the relationship does not appear to be particularly strong or consistent. Relative to plausibility, some hypothesize that obesity leads to esophageal reflux resulting in worse asthma; this has not been systematically evaluated. Another plausible hypothesis is that obesity is associated with a low grade state of chronic inflammation which could contribute to airway inflammation and airway hyperreactivity. However, in most studies, the levels of cytokines in peripheral blood are quite low (17, 18). In addition, in one report, exhaled nitrogen oxide, known to correlate with airway inflammation in asthma was not elevated in obese individuals as compared to those who were non-obese (19). Moreover, a study of adults reported no association between BMI and airway inflammation as measured by sputum cell counts (20). These findings suggest that the relationship between asthma and obesity may not be causative, but related to other factors in a shared pathway of obesity and asthma.

Our sample of urban adults with asthma was derived from the Chicago Initiative to Raise Asthma Health Equity (CHIRAH) project, one of the NHLBI Centers of Excellence in Reducing Asthma Disparities. The primary activity of the CHIRAH project has been to conduct a community-based cohort study to better characterize those factors that are contributing to racial/ethnic disparities with the purpose of finding modifiable factors that may provide the basis of new intervention strategies to eliminate these disparities. Obesity could be such a modifiable factor. The CHIRAH study therefore provides a unique opportunity to report on a population-based understanding of burden of asthma in a large urban environment known to have one of the highest asthma mortality rates in the U.S.

This study examines the association of obesity, as measured by BMI, with AQLQ score and with asthma specific healthcare utilization in a community-based sample of adults with asthma living within the city limits of Chicago. In this population of adults with asthma, obesity was associated with worse AQLQ as measured by the short form of the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (mini-AQLQ) (21). Studies of asthma and obesity published to date have not specifically focused on urban adults with asthma, nor are most of them community-based, making our observations unique.

METHODS

Study design

The details of the design of the CHIRAH project have been described elsewhere (22). We utilized only cross sectional data from the first face to face interview of 352 adult subjects with asthma.

Study sample

This sample of urban adults with asthma was identified using population proportionate sampling of children attending Chicago public and archdiocesan elementary schools. Both children and adult family members with asthma were recruited. It is from the latter than our study sample was drawn.

Inclusion criteria

Subjects had to be aged 18 to 40, live within the city limits of Chicago, have a telephone, be fluent in English, and have physician diagnosed asthma with symptoms requiring asthma medications at least 8 weeks out of the previous year.

Study variables

Demographic, social, and clinical variables were gathered in a survey format administered by trained research assistants. These included direct queries as to age, sex, race, smoking history, highest level of education, and annual household income (one of 4 ranges <$15,000; 15,000–30,000; 30,000–50,000; >50,000). Subjects were also queried about employment, home ownership, medical insurance (public, private or none), asthma duration (number of years), beta agonist use (number of days in past 2 weeks), number of days with asthma symptoms in the past 2 weeks, number of nights with asthma symptoms in the past 2 weeks, number of urgent care or emergency room visits for asthma in the past 12 months, and number of hospitalizations for asthma in the past 12 months. Standing height, using a stadiometer, and weight, using a calibrated digital scale, were measured to calculate BMI. Obesity was defined as ≥30 kg/m2. Spirometry (SpiroPro® VIASYS Healthcare, Conshohocken, PA) was performed pre and post bronchodilator, following guidelines of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (23).

Depression score was obtained using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D), a 20 item screen for depression in the general adult population. (24). Scores range from 0 to 60, with scores above 15 suggestive of a depressive disorder.

Socioeconomic status (SES) was quantified as previously described. (25) Variables included income, education, employment, health insurance and home ownership.

Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) score, the primary asthma outcome measure, was obtained from the mini Juniper AQLQ, an instrument with 15 items that can be categorized into 4 domains: symptoms, activity limitations, emotional function, and environmental stimuli. (21) The response ranges from 1 to 7 with higher scores representing higher quality of life. The instrument has documented reliability, construct validity, and responsiveness, with a difference of 0.5 or greater considered clinically relevant.

Statistical analyses

Bivariate tests, including Chi Square, t-tests and Pearson correlations were used, as appropriate, to assess the relationship between BMI as a continuous variable or obesity status (BMI < 30 kg/m2) and asthma outcome variables, specifically AQLQ scores and number of emergency department (ED)/urgent care visits for asthma in the prior year. Multivariate regression analyses were then performed to predict AQLQ score which was the primary asthma outcome. Variables that were controlled for included age, race, gender, income, education, depression score, and beta agonist use. (SAS 3.2; Cary, NC)

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics: demographic, social and clinical

Demographic variables are listed in Table I, according to weight groupings of non- obese (BMI < 30 kg/m2) and obese. Obese participants were statistically more likely to be older, female, African American, from low income households (<$15,000/yr), and have asthma 2.2 years longer than those participants who were not obese. There were no differences between obese and non-obese participants in education, type of medical insurance, pre-bronchodilator FEV1% predicted, smoking history, or depression score.

Table I.

Demographic Characteristics of Sample

| VARIABLE | Non-Obese BMI < 30 n=161 (%) |

Obese BMI ≥ 30 n=191 (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 30.0 ± 6.4 | 31.7 ± 5.7 | 0.01 |

| Gender, Female | 121 (75.2) | 153 (80.1) | 0.002 |

| Race, African American | 77 (47.8) | 127 (66.5) | <0.001 |

| Education < High school | 22 (13.7) | 37 (19.4) | 0.10 |

| High school/GED graduate | 107 (66.5) | 130 (68.1) | |

| College graduate | 32 (19.9) | 24 (12.6) | |

| Medical insurance Medicaid | 63 (39.4) | 82 (42.9) | 0.74 |

| Private insurance | 76 (47.5) | 83 (43.5) | |

| Self-pay | 21 (13.1) | 26 (13.6) | |

| HH income, per yr < $15,000 | 38 (23.6) | 61 (31.9) | 0.002 |

| $15,000 – $30,000 | 45 (28.0) | 45 (23.6) | |

| $30,000 – $50,000 | 25 (15.5) | 39 (20.4) | |

| > $50,000 | 53 (32.9) | 46 (24.1) | |

| Duration of Asthma Diagnosis, yr | 16.7 ± 9.9 | 18.9 ± 10.6 | 0.04 |

| FEV1 mean % predicted pre-bronchodilator | 88.2 ± 18.0 | 86.1 ± 18.8 | 0.31 |

| Smoking History | 52 (32.5) | 51 (26.8) | 0.25 |

| Current Smoker | |||

| > 100 cigarettes in lifetime | 71 (44.4) | 73 (38.4) | 0.26 |

| CES-D Depression Score | 16.3 ± 11.4 | 15.3 ± 10.4 | 0.41 |

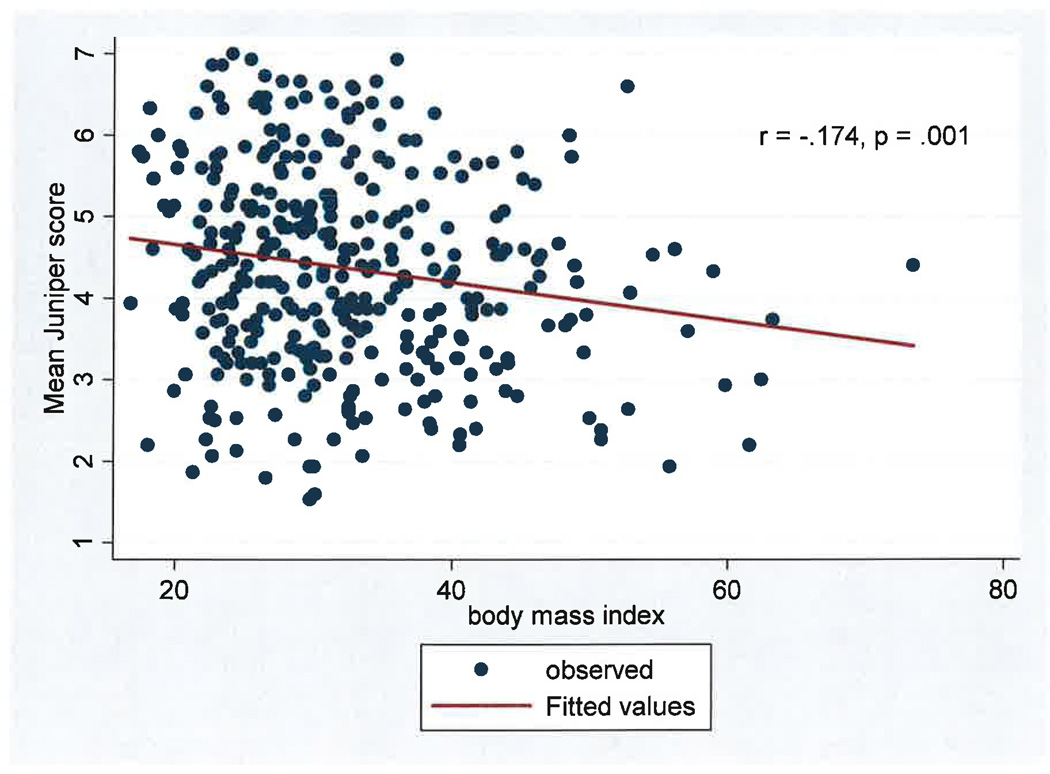

BMI and Juniper mini AQLQ

Overall Juniper mini AQLQ scores were negatively correlated with BMI, (r= −0.174, p= 0.001) as shown in Figure 1. On average, for each increase of 1 kg/m2, there was a decrease of 0.025 in the AQLQ score. The negative correlations between BMI and Juniper subscales were consistent in each domain. (Symptoms r= −0.139, p=0.009; Activity Level r= −0.172, p=0.001; Emotional function r= −0.106, p=0.046; Environmental stimuli r= −0.169, p= 0.001).

Figure 1. BMI and Mean Juniper Mini AQLQ Score.

In this population of young (ages 18 to 40) inner city adults with asthma, there is a significant negative correlation between BMI and mean Juniper mini Asthma Quality of Life Score.

BMI and Urgent Health Service Use

BMI was statistically significantly higher in those subjects requiring ED/urgent care visits as compared to those who did not. (33.8 kg/m2 vs 30.5 kg/m2 p=0.001)..

Regression analysis for mean mini AQLQ score

Using multivariate regression analysis, the relative contribution of co-variates such as BMI, education level, and depression score, to the mini AQLQ score was assessed. As listed in Table II, a negative relationship between BMI and AQLQ was observed. (β-Coefficient = −0.016; p=0.011).

Table II.

Independent Predictors of AQLQ Score in Multivariable Regression

| Predictor Variable | β Coefficient | p value |

|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.016 | 0.011 |

| Age (yr) | −0.010 | 0.288 |

| Sex (female) | −0.251 | 0.066 |

| Race (AA) | 0.045 | 0.696 |

| Education (college graduate) | 0.442 | 0.009 |

| Income (> $50,000 per yr) | 0.287 | 0.043 |

| CES-D (total score, 1–60) | −0.038 | <0.0001 |

| Beta-agonist use (#days in last 2 weeks) | −0.073 | <0.0001 |

Assessing the relative effect of BMI on AQLQ

To assess the effect of BMI and other variables on AQLQ, we evaluated multiple models, adding each measure in a hierarchical manner. As shown in Table III, sequentially adding socioeconomic status (SES), BMI, CES-D and beta-agonist use to a basic model increased the explanatory power of the predictive model for AQLQ, as indicated by a significant change in the model R2. In total, this model explained 35% of the observed variance in AQLQ.

Table III.

Relative Contribution of BMI to AQLQ

| Model | R2 | Change in Model R2 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic* | 0.0248 | NA | NA |

| Basic + SES** | 0.1101 | 0.085 | < 0.0001 |

| Basic + SES + BMI | 0.1217 | 0.012 | 0.0340 |

| Basic + SES + BMI + CES-D | 0.2452 | 0.124 | < 0.0001 |

| Basic + SAS + BMI + CES-D + Beta-agonists use | 0.3479 | 0.103 | < 0.0001 |

Basic = age, race, gender

SES = education, income, medical insurance, employment, home ownership

BMI and other asthma outcomes

Although the data are not shown, we analyzed BMI in relation to other asthma outcomes. BMI did not correlate with pre-bronchodilator FEV1% predicted (r=−0.015, p=0.794) nor was BMI different in those hospitalized compared to those not hospitalized for asthma in the prior year (32.9 kg/m2 vs 32.4 kg/m2 p=0.729). BMI did not correlate with number of nights with asthma symptoms in the past 2 weeks (r= 0.052; p=0.331) but did show a weak correlation with number of days with asthma symptoms in the past 2 weeks (r= 0.104; p=0.052).

DISCUSSION

In this community based study of young adults, age 18 to 40, with asthma, we report that subjects with a higher BMI were more likely to be female, African American, older or from lower income households. We also found that obesity was associated with worse asthma-specific quality of life; in particular, BMI was inversely correlated to mini AQLQ score overall, and in turn, to each of the 4 domains measured. In addition, a higher BMI was associated with asthma related emergency department or urgent care visits. This study is unique in that it is community-based and was conducted in Chicago, an urban environment that currently has one of the very highest asthma mortality rates in the U.S. If obesity is a modifiable risk factor that may contribute to asthma and asthma disparities, it would be of obvious importance.

Many other studies have reported that asthma morbidity, as measured by a variety of outcomes is higher in obese as compared to non-obese individuals. (5–8) We found that emergent or urgent physician visits for asthma were more common in those with higher BMI. However, we did not find differences in hospitalization rate as has been reported by some others.(26) Whether this is due to the community-based nature of our population or some other factors is not clear. We also did not find any correlation between BMI and an objective measure of lung function, FEV1% predicted. In a recent study evaluating a clinic based urban population, there was no consistent relationship between BMI and FEV1%. (27) In that study, the overweight group (BMI 25–29.9) had a higher mean FEV1% than the normal weight group.

In this study, using multivariate regression analysis, we were also able to evaluate the relative contribution of factors, other than BMI, to mean AQLQ score. Some of the factors that contributed were immutable, with both race and sex having β coefficients with higher absolute value than BMI, but neither of which was statistically significant. Mutable factors that were statistically significant and had β coefficients with higher absolute value than BMI included education, income, depression score and beta agonist use.

There are a number of limitations of this study. Given the cross sectional nature of the study, there was no temporal assessment to determine whether change in BMI would result in change in AQLQ score. Our measure of obesity was BMI which most other studies of asthma and obesity have used. However, a measure of central obesity such as waist/ hip ratio or waist circumference may be more informative, just as such measures are more useful in predicting cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. This study excluded individuals over the age of 40, thus limiting its relevance to older asthma populations. Finally, the asthma outcome analysis comparing BMI and AQLQ score revealed a rather modest correlation coefficient although this was significant because of the large number of subjects.

In summary, this is the only community-based study of young urban adults that has evaluated obesity. We have identified BMI as a modifiable risk factor associated with lower mean and subscale specific AQLQ scores and with more emergent/urgent care visits after controlling for age, gender, and race. However, an objective measure of asthma, the FEV1% predicted did not correlate at all with BMI. Furthermore, the relative contribution of BMI to AQLQ scores was modest as compared to other factors such as depression. The relationship between obesity and asthma outcomes should be studied in additional urban community or population based samples as this could explain one factor contributing to asthma disparities. Differentiating between central and overall obesity, correlating obesity types and severity with objective measure of lung function, and levels of inflammatory markers such as adipokines, IL-6, and TNF-α may further clarify the relationship between asthma and obesity.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute 1 U01 HL072496-05; The Ernest S Bazley Grant to Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Northwestern University

REFERENCES

- 1.Joseph CLM, Williams LK, Ownby DR, Saltzgaber J, Johnson CC. Applying epidemiologic concepts of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention to the elimination of racial disparities in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canino G, McQuaid EL, Rand CS. Addressing asthma health disparities: a multilevel challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1209–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gold DR, Wright R. Population disparities in asthma. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:89–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apter AJ. The influence of health disparities on individual patient outcomes: What is the link between genes and environment? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beuther DA, Weiss ST, Sutherland ER. Obesity and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:112–119. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-231PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akerman MJH, Calacanis CM, Madsen MK. Relationship between asthma severity and obesity. J Asthma. 2004;41:521–526. doi: 10.1081/jas-120037651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beuther DA, Sutherland ER. Overweight, obesity, and incident asthma: A Meta-analysis of prospective epidemiologic studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:661–666. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200611-1717OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavoie KL, Bacon SL, Labrecque M, Cartier A, Ditto B. Higher BMI is associated with worse asthma control and quality of life but not asthma severity. Resp Med. 2006;100:648–657. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aaron SD, Fergusson D, Dent R, Chen Y, Vandemheen KL, Dales RE. Effect of weight reduction on respiratory function and airway reactivity in obese women. Chest. 2004;125:2046–2052. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.6.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakala K, Stenius-Aarniala B, Sovijarvi A. Effects of weight loss on peak flow variability, airways obstruction, and lung volumes in obese patients with asthma. Chest. 2000;118:1315–1321. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.5.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stenius-Aarniala B, Puossa T, Kvarnstrom J, Gronlund EL, Ylikahri M, Mustajoki P. Immediate and long term effects of weight reduction in obese people with asthma: randomised controlled study. BMJ. 2000;320:827–832. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7238.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sood A. Does obesity weigh heavily on the health of the human airway? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:921–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford ES. The epidemiology of obesity and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shore SA, Johnston RA. Obesity and asthma. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;110:83–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waggoner D, Stokes J, Casale TB. Asthma and obesity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008:641–643. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLachlan CR, Poulton R, Car G, Cowan J, Filsell S, Greene JM, et al. Adiposity, asthma, and airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:634–639. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fantuzzi G. Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:911–919. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shore SA. Obesity and asthma: cause for concern. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazaks A, Uriu-Adams JY, Stern JS, Albertson TE. No significant relationship between exhaled nitric oxide and body mass index in people with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:929–930. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barros R, Moreira A, Fonseca J, Moreira P, Fernandes L, Oliveira JF, et al. Obesity and airway inflammation in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1501–1502. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of the Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:32–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a08.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss KB, Shannon JJ, Sadowski LS, Sharp LK, Curtis L, Lyttle CS, et al. The burden of asthma in the Chicago community fifteen years after the availability of national asthma guidelines: The design and initial results from the CHIRAH study. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 1009;30:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brusasco V, Crap R, Viegi G. American Thoracic Society. European Respiratory Society. Coming together: The ATS/ERS consensus on clinical pulmonary function testing. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:1–2. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radloff LS. The CES-D: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans AT, Sadowski LS, VanderWeele TJ, Curtis LM, Sharp LK, Kee RA, et al. Ethnic disparities in asthma morbidity in Chicago. J Asthma. 2009;46:448–454. doi: 10.1080/02770900802492061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosen DM, Schatz M, Magid DJ, Camargo CA. The relationship between obesity an d asthma severity and control in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:507–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clerisme-Beaty EM, Karam S, Rand C, Patino CM, Bilderback A, Riekert KA, et al. Does higher body mass index contribute to worse asthma control in an urban population? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]