Abstract

An understanding of the biological roles of lectins will be advanced by ligands that can inhibit or even recruit lectin function. To this end, glycomimetics, non-carbohydrate ligands that function analogously to endogenous carbohydrates, are being sought. The advantage of having such ligands is illustrated by the many roles of the protein DC-SIGN. DC-SIGN is a C-type lectin displayed on dendritic cells, where it binds to mannosides and fucosides to mediate interactions with other host cells or bacterial or viral pathogens. DC-SIGN engagement can modulate host immune responses (e.g., suppress autoimmunity) or benefit pathogens (e.g., promote HIV dissemination). DC-SIGN can bind to glycoconjugates, internalize glycosylated cargo for antigen processing, and transduce signals. DC-SIGN ligands can serve as inhibitors as well as probes of the lectin’s function, so they are especially valuable for elucidating and controlling DC-SIGN’s roles in immunity. We previously reported a small molecule that embodies key features of the carbohydrates that bind DC-SIGN. Here, we demonstrate that this non-carbohydrate ligand acts as a true glycomimetic. Using NMR HSQC experiments, we found that the compound mimics saccharide ligands: It occupies the same carbohydrate-binding site and interacts with the same side chain residues on DC-SIGN. The glycomimetic also is functional. It had been shown previously to antagonize DC-SIGN function but here we use it to generate DC-SIGN agonists. Specifically, appending this glycomimetic to a protein scaffold affords a conjugate that elicits key cellular signaling responses. Thus, the glycomimetic can give rise to functional glycoprotein surrogates that elicit lectin-mediated signaling.

Carbohydrate-lectin interactions are crucial for many biological processes, including cellular adhesion, migration, signaling, and infection (1). Because carbohydrates are displayed on the exterior of all cells, lectins have critical roles in immunity and tolerance. One large family of lectins that can function in this capacity is the C-type lectin class, whose members are named for their dependence on calcium ions to facilitate carbohydrate binding by chelation to carbohydrate hydroxyl groups (2). Several members of this class are found on dendritic cells (DCs), the major antigen-presenting cells of the immune system (3), where they can function as antigen receptors and control DC migration and interactions with other immune cells (4, 5). These multiple functions all contribute to mounting appropriate immune responses. One DC receptor, dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN), is an intriguing lectin with varied functions (6, 7). Through its interactions with high mannose glycans or fucose-containing Lewis-type antigens on self-glycoproteins ICAM-3 and ICAM-2, DC-SIGN can mediate T cell interactions and trans-endothelial migration, respectively (8, 9). It also has been implicated in antigen processing because it promotes uptake of anti-DC-SIGN antibodies for processing and presentation to T cells (10). Although these data emphasize the roles of DC-SIGN in giving rise to immune responses, the lectin can interact with a variety of glycosylated pathogens to facilitate infection. For example, DC-SIGN binds to the mannosylated surface glycoprotein gp120 on HIV to mediate trans-infection of T cells (11, 12). The infectious agent Mycobacterium tuberculosis exploits DC-SIGN interactions for a different end. The bacteria which display a mannosylated surface component, are internalized and processed via interactions with DC-SIGN. The outcome is a dampening of pro-inflammatory signaling and inhibition of DC maturation, leading to immunosuppression (13).

Identification of the roles DC-SIGN can play in pathogenesis has prompted efforts to identify chemical inhibitors. DC-SIGN binds weakly to monosaccharides such as N-acetyl mannosamine (ManNAc, Kd = 8.7 mM) and l-fucose (Kd = 6.7 mM) (14). Oligosaccharides bind with slightly higher affinities (e.g. Man9GlcNAc has a Kd of 0.21 mM). These observations, in conjunction with the finding that DC-SIGN is tetrameric, have prompted the exploration of multivalent presentation as a strategy to generate potent inhibitors (14–16). Several multivalent glycan inhibitors have been developed (17–20); however, a complication of studying DC-SIGN in natural settings is the presence of additional C-type lectins that have similar specificities (4). Oligomannose and oligofucose ligands may therefore interact with multiple lectins, complicating the dissection of DC-SIGN function in vivo. Thus, alternative approaches are necessary to generate compounds with more specificity as well as higher affinity for DC-SIGN.

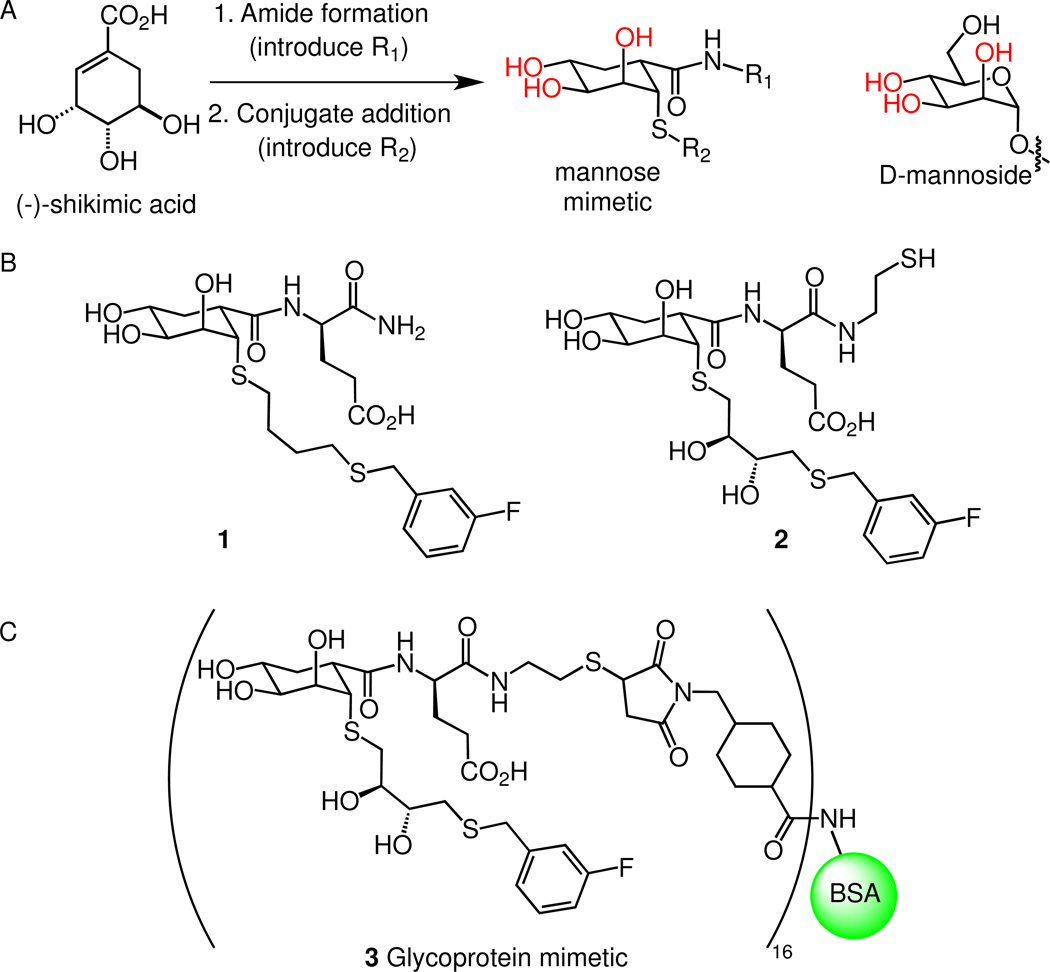

We have synthesized small molecules that serve as ligands for DC-SIGN (21–23). To this end, we have sought to devise new types of glycomimetics as ligands. The term glycomimetic has been applied widely, and it often is used to refer to lectin-binding compounds in which some or even most glycosidic linkages are preserved. Carbohydrate derivatives of this type that bind DC-SIGN have been identified and can be more potent inhibitors than canonical carbohydrate ligands (24–28). Here, we define “glycomimetic” to mean a compound that is lacking standard glycosidic linkages but that resembles a carbohydrate and can mimic or inhibit its function. We therefore set out to identify non-carbohydrate building blocks that would possess the critical features of the carbohydrates that bind DC-SIGN. Specifically, we have used (−)-shikimic acid as a scaffold to generate compounds designed to function as mannoside or fucoside surrogates (29, 30). The natural product (−)-shikimic acid was subjected to amide formation followed by conjugate addition of a thiolate to afford a compound with hydroxyl groups in the requisite stereochemical arrangement to mimic d-mannosides. This strategy yields compounds wherein several positions can be modified to take advantage of secondary-site interactions to increase binding affinity and specificity. We previously used the approach to generate DC-SIGN inhibitors (23). One lead compound, triol 1, was about four-fold more active than ManNAc. A polymer bearing the compound exhibited an increase in potency of approximately 1,000-fold. These studies validate the utility of multivalency for designing non-carbohydrate mimics of natural carbohydrates and glycoproteins.

A major issue was whether compound 1 could serve as a functional mimic of the saccharides that bind DC-SIGN. NMR experiments with recombinant DC-SIGN reveal the addition of compound 1 results in the types of chemical shift perturbations caused by mannose and fucose. We leveraged the similarity of the binding modes of carbohydrates and the glycomimetic to generate a glycoprotein surrogate that acts as a DC-SIGN agonist. The resulting conjugate is internalized by DC-SIGN-expressing cells and initiates cellular signaling. These findings highlight the potential of synthetic ligands for exploring the diverse roles of DC-SIGN.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemical Shift Perturbation Analysis of Glycomimetic Binding

While compound 1 serves as an effective inhibitor, its mechanism of inhibition was not known. The scaffold was designed to interact with the carbohydrate recognition domain of DC-SIGN, but as with most putative glycomimetics, structural information regarding the mode of binding of compound 1 to DC-SIGN was lacking. Such information is important if glycomimetics and glycoprotein surrogates are to be used to probe and control lectin function. For example, antibodies that interact with DC-SIGN at sites other than its carbohydrate recognition domain fail to trigger DC-SIGN internalization (10). Thus, for synthetic ligands to be effective cellular probes of DC-SIGN function they should mimic glycan binding. We therefore sought a method to determine whether compound 1 engages DC-SIGN in the same manner as carbohydrate ligands.

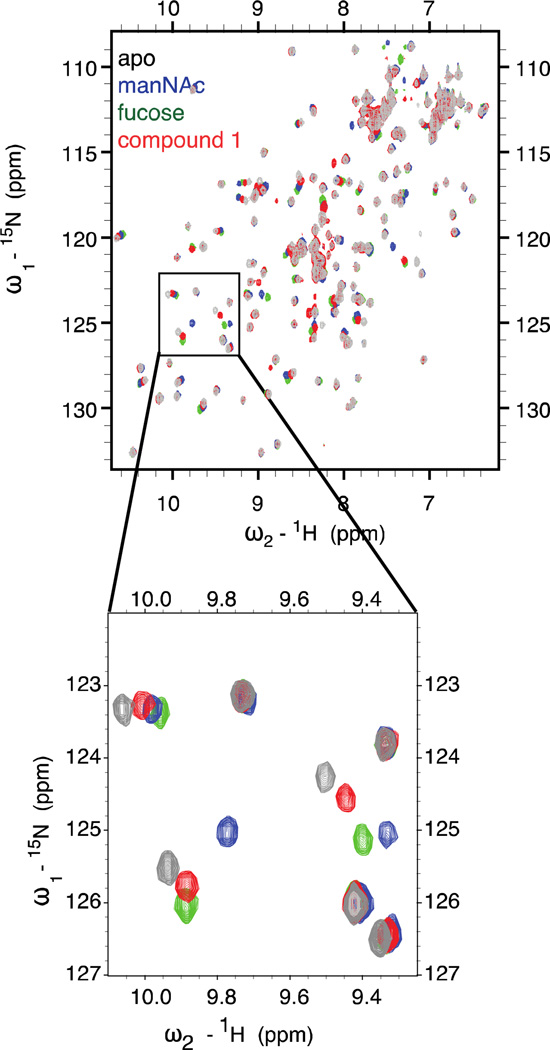

Our strategy was to employ NMR spectroscopy to monitor binding of different ligands to the DC-SIGN carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) (Figure 2). We reasoned that 1H-15N HSQC experiments would be valuable for this purpose as they reveal chemical shift perturbations of backbone amide NMR resonances upon ligand addition (31). Because chemical shifts are so sensitive to environment, perturbations can be valuable indicators of ligand binding. This method is especially illuminating when complexation occurs with minimal protein conformational change. We postulated that the C-type lectins would be excellent substrates for analysis using this method because the data from x-ray crystallographic analysis indicates that the bound and unbound structures of these proteins are similar (32). Consequently, we anticipated that HSQC shift perturbations would be localized to residues in the ligand-binding site. To this end, spectra were collected of unbound (apo) DC-SIGN and of the lectin in the presence of N-acetyl mannosamine (ManNAc), fucose (Fuc), or compound 1.

Figure 2. Glycomimetic interacts with DC-SIGN in the sugar binding pocket.

Superimposed two-dimensional HSQC spectra are shown of DC-SIGN CRD apo (gray) or in the presence of 20 mM N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc) (blue), fucose (green) or compound 1 (red). The inset highlights a region of the spectrum containing three signals that undergo significant shifts upon ligand binding.

When ManNAc or fucose was added, a subset of peaks shifted compared to the apo spectrum, indicating that the corresponding residues were affected by ligand binding (Figure 2). That the addition of each type of carbohydrate afforded similar chemical shift perturbations is consistent with structural data indicating that the modes by which these saccharides engage DC-SIGN are analogous (for a list of relevant chemical shifts, see Figure S1). The structures determined from crystallographic analysis also indicate that nearly identical lectin side chains participate in binding to either N-acetylmannosamine or fucose, and our NMR data are consistent. These results highlight the value of 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectroscopy for studying ligand binding to a C-type lectin, and we posit that this approach will be useful for future studies of proteins in this class

When we tested compound 1, its addition resulted in similar chemical shift perturbations. These findings indicate that compound 1 has a binding mode analogous to that of saccharide ligands. In addition, several peaks appeared upon glycomimetic addition that were not present in any of the other spectra (Figure 2). The appearance of these peaks is consistent with the conformational restriction of residues that were flexible in the apo form. Thus, some conformational heterogeneity exists in the apo protein, and the glycomimetic appears to be unique among ligands tested in its ability to decrease this heterogeneity. These data suggest that there are glycomimetic-specific interactions with DC-SIGN, which presumably arise from binding to adjacent secondary sites. They also augur well for optimization of the glycomimetic by enhancing its secondary site interactions. Overall, these data demonstrate that the molecular basis of the interaction of compound 1 with DC-SIGN parallels that of N-acetylmannosamine and fucose. It is therefore deserving of the term “glycomimetic.”

A Glycoprotein Surrogate Undergoes DC-SIGN-Mediated Uptake

Given that compound 1 mimics the interactions of carbohydrates with DC-SIGN we next tested whether it would promote the cellular functions of DC-SIGN. While other synthetic ligands have been shown to inhibit DC-SIGN, none have been shown to act as functional agonists. There are two critical functions that DC-SIGN agonists can promote: antigen internalization and activation of signaling pathways. Both types of processes should be facilitated by clustering of DC-SIGN. Thus, we generated multivalent versions of our glycomimetic by appending compound 2, a dihydroxylated analog of compound 1, to bovine serum albumin (BSA). Derivative 2 binds to DC-SIGN with affinity similar to that of compound 1, but it is more water soluble (23). Compound 2 was appended to BSA (~16 copies, see the Supplementary Information) and the resulting conjugate was coupled to an AlexaFluor® 488 dye equipped with an N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester to yield a fluorophore labeled glycoprotein mimic. The fluorophore was similarly attached to mannose substituted-BSA and fucose substituted-BSA. The resulting glycoprotein conjugates and the glycoprotein surrogate were assessed in several assays.

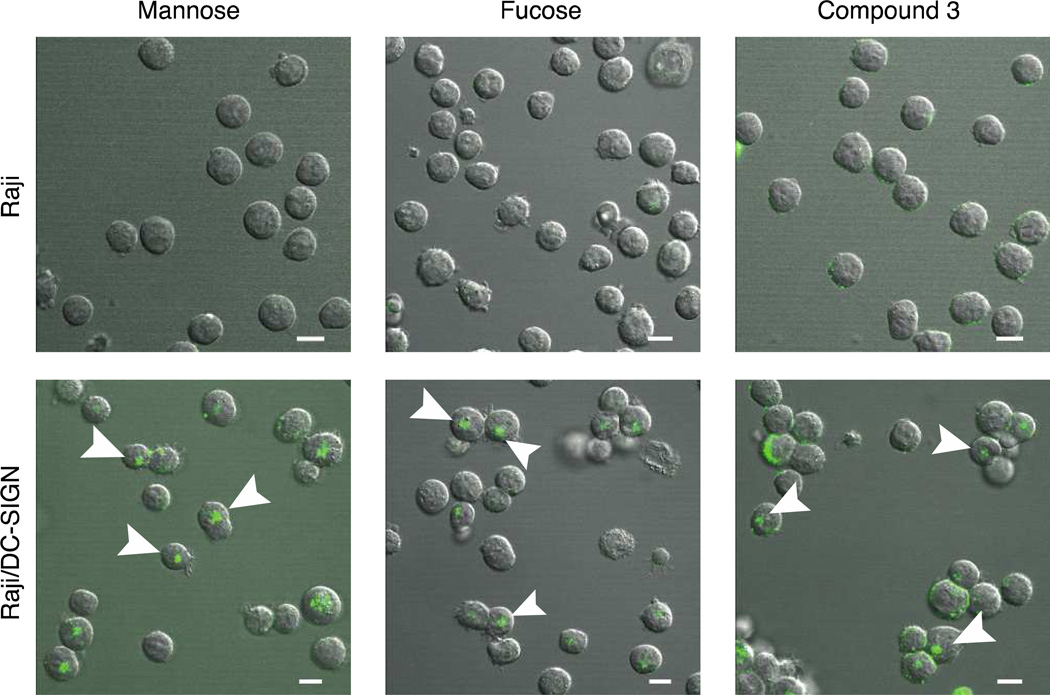

We first tested the ability of the glycoconjugates and glycoconjugate mimic to undergo DC-SIGN-mediated endocytosis. The cytoplasmic tail of DC-SIGN contains conserved internalization motifs, and anti-DC-SIGN antibodies are taken up by dendritic cells, processed, and presented to T cells (10). If synthetic glycomimetic conjugates like 3 are endocytosed, they could be used as novel vaccines to deliver antigens to dendritic cells. The observation that HIV is not processed following engagement of DC-SIGN (11, 12), however, suggests that cargo that interacts with DC-SIGN can have other fates. The ability to generate tailored DC-SIGN ligands therefore provides the opportunity to examine what factors influence DC-SIGN-mediated internalization. To assess the feasibility of this approach, confocal microscopy was used to monitor DC-SIGN-specific internalization of fluorescent conjugates: mannose-BSA, fucose-BSA and glycomimetic-BSA (compound 3, Figure 3). Each glycoconjugate or the glycoprotein mimetic was exposed to Raji cells, a human B cell line derived from Burkitt’s lymphoma, or Raji cells stably transfected with the gene encoding DC-SIGN (Raji/DC-SIGN) (33). Mannosylated and fucosylated BSA conjugates were internalized by the Raji/DC-SIGN but not the Raji cells (Figure 3). These results indicate that uptake of the carbohydrate-decorated proteins depends on the presence of DC-SIGN. The glycoprotein surrogate also was internalized only by the DC-SIGN-expressing cells. Thus, the glycoprotein mimic undergoes DC-SIGN-mediated uptake, thereby acting in accord with glycoconjugates decorated with carbohydrates. The data indicate that a specific lectin can be targeted to deliver cargo to a cell’s interior using a glycomimetic or glycoprotein surrogate.

Figure 3. Glycocoprotein surrogate is internalized by DC-SIGN-expressing cells.

Raji cells (top panels) and Raji/DC-SIGN cells (bottom panels) were treated with glycoconjugates mannose-BSA-AF488 (left), fucose-BSA-AF488 (center) or compound 3 (right). After exposure to glycoconjugate or glycomimetic conjugate, live cells were imaged by confocal microscopy. Examples of punctate intracellular staining are indicated by white arrows. Scale bars indicate 10 µm.

Initiation of Cell Signaling by the Glycoprotein Surrogate

Ligand binding to DC-SIGN can promote cellular signaling (34). A critical functional test our glycoprotein surrogate is whether it can elicit signaling. The ability of a synthetic ligand to elicit cellular signals opens new avenues of investigation. Some pathogens are known to modulate DC-SIGN-mediated signaling, but the mechanisms by which they do so have not been fully elucidated (13, 35–37). If chemically defined DC-SIGN agonists can initiate signaling events, they can be crafted to reveal how ligand structure modulates signal output. Such information could guide the design of compounds that modulate DC-SIGN-mediated signaling to enhance immunity and thereby combat infection or to suppress unwanted immune responses. A clinically important role for DC-SIGN in regulating immune responses has emerged from investigations of the mechanism of action of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) (38). This blood product, composed of pooled IgG antibodies, is used for a number of different purposes, one of which is to suppress deleterious inflammation. DC-SIGN interacts with endogenous sialylated Fc to upregulate IL-33, a cytokine that can suppress serum-induced arthritis (39). As such, ligands that trigger DC-SIGN-mediated signaling may act as novel agents to combat inflammatory and immune diseases. Accordingly, we tested whether our glycoconjugate surrogate initiates signaling via DC-SIGN.

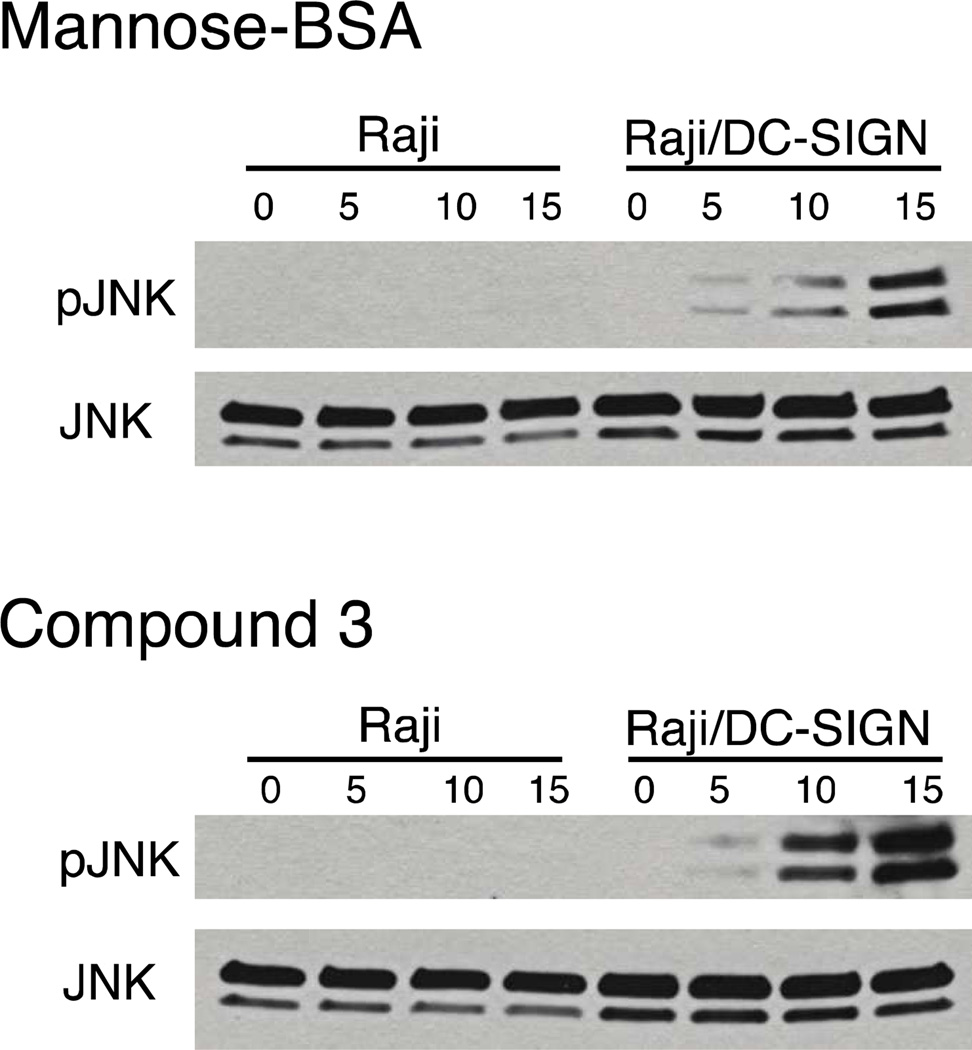

We focused our analysis on the JNK pathway, which has been implicated in DC-SIGN-mediated immune signaling (40, 41). JNK is a mitogen-activated protein kinase that is linked to dendritic cell maturation and the response to “danger” signals (42) The net result is changes in gene expression via downstream effects on a variety of transcription factors, including c-Jun. When Raji or Raji/DC-SIGN cells were treated with mannose-substituted BSA the level of phospho-JNK was increased. Modest enhancement was detected after five minutes, while larger increases were observed at later time points (10 and 15 min) (Figure 4). The increases in phospho-JNK depend on the presence of DC-SIGN. Intriguingly, cellular responses to glycoprotein surrogate 3 paralleled those obtained with the mannose-substituted glycoconjugate. Our data indicate that the glycoprotein surrogate effectively initiates signaling events. Thus, our strategy provides the means to probe how the structures of different glycoconjugates influence DC-SIGN-mediated cellular responses.

Figure 4. Glycoprotein surrogate stimulates DC-SIGN-mediated JNK signaling.

Raji or Raji/DC-SIGN cells were treated with mannose-BSA (top) or compound 3 (bottom) and incubated at 37 °C for the indicated time (min). Samples were subject to lysis, products were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the gels analyzed by immunoblotting for phospho-JNK (pJNK). Blots were then stripped and re-probed for JNK to assess the total protein loaded in each lane.

Conclusions

In summary, we synthesized a glycomimetic that is functionally equivalent to glycans that bind DC-SIGN. The utility of DC-SIGN ligands relies on their ease of synthesis and the opportunities for their chemical manipulation to explore and/or trigger specific cellular responses. To interpret functional data from such probes, however, the probes must mimic glycan ligands in binding to their target lectin. The shikimic acid-based glycomimetic we have devised does just this that. Accordingly, it merits the descriptor “glycomimetic.” Our results also highlight the utility of NMR shift perturbations for identifying and comparing glycan binding sites within lectins. Finally, we show that our glycomimetic can be used to generate a glycoprotein surrogate that acts as a full DC-SIGN agonist: it is capable of initiating DC-SIGN-mediated internalization and signaling. Thus, we have identified a probe of DC-SIGN that goes beyond inhibition. We therefore anticipate that compounds 1 and 3 can be used to interrogate DC-SIGN function.

These data also serve as validation that shikimic acid can serve as a useful scaffold to generate non-carbohydrate glycomimetics. Compound 1 is a starting point to optimize probes for specific attributes, such as broad activity for subsets of C-type lectins, increased affinity or enhanced DC-SIGN binding specificity. Our group has also recently described a related approach to generate fucoside mimics based on (−)-4-epi-shikimic acid (30), and we anticipate that compounds of this class can be converted into agonists for fucose-binding lectins. We envision a general glycomimetic approach based on different shikimic acid scaffolds that will allow for generation of a wide range of compounds useful for specifically inhibiting undesirable lectin interactions with pathogens, as well as for elucidating the biological functions of immune lectins. We expect that the strategy that we have described here can serve as a blueprint to devise synthetic ligands can promote lectin signaling.

METHODS

Cells and constructs

Raji and Raji/DC-SIGN cells were obtained from the NIH AIDS Reference and Reagent Program (33). Cells were maintained in RPMI (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% carbon dioxide. A plasmid for expressing DC-SIGN carbohydrate recognition domain (residues 250–404) was obtained from Kurt Drickamer (14) and transformed into E. coli strain BL21/DE3.

Chemical methods

Full synthesis and characterization of compound 2 and glycoconjugate 3 is provided in the supporting information. Mannose and fucose glycoconjugate probes were generated by coupling an AF488 succinimidyl ester (Invitrogen) to mannose-BSA and fucose-BSA (Dextra) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting surrogates were purified using a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare) and dialysis into PBS.

NMR spectroscopy, confocal microscopy and Western blotting are described in detail in the supplemental information.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1. Strategy for glycomimetic design.

(A) Three key polar hydroxyl groups (red) on mannosides contribute to C-type lectin binding (32). Compounds can be synthesized from (−)-shikimic acid with hydroxyl groups in the relevant orientations that mirror d-mannosides. (B) Lead compound 1 and hydroxylated analog 2 bearing a cysteamine moiety are inhibitors of DC-SIGN (23). (C) Compound 2 was appended to BSA and the conjugate was converted into fluorescent glycoprotein surrogate 3.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the NIH (NIGMS GM049975 and R01AI055258). We thank K. Drickamer for providing the DC-SIGN expression vector. Stably transfected DC-SIGN Raji cells were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH from L. Wu and V. N. Kewal-Ramani. Confocal microscopy was performed at the W.M. Keck Laboratory for Biological Imaging at the UW–Madison, and we gratefully acknowledge L. Rodenkirch for assistance. This study made use of the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison, which is supported by NIH grants P41RR02301 (BRTP/ NCRR) and P41GM66326 (NIGMS). Additional equipment was purchased with funds from the University of Wisconsin, the NIH (RR02781, RR08438), the NSF (DMB-8415048, OIA-9977486, BIR-9214394), and the USDA. The UW-Madison Chemistry NMR facility is supported by the NSF (CHE-0342998 and CHE-9629688) and the NIH (1-S10-RR13866). L.R.P. is an NIH postdoctoral fellow (GM089084).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information Available: Methods and synthetic procedures. This material is free via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Varki A. Biological roles of oligosaccharides: all of the theories are correct. Glycobiology. 1993;3:97–130. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weis WI, Crichlow GV, Murthy HM, Hendrickson WA, Drickamer K. Physical characterization and crystallization of the carbohydrate-recognition domain of a mannose-binding protein from rat. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20678–20686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinman RM. Dendritic cells: understanding immunogenicity. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(Suppl 1):S53–S60. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Figdor CG, van Kooyk Y, Adema GJ. C-type lectin receptors on dendritic cells and Langerhans cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:77–84. doi: 10.1038/nri723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson MJ, Sancho D, Slack EC, LeibundGut-Landmann S, Reis e Sousa C. Myeloid C-type lectins in innate immunity. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1258–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geijtenbeek TB, Engering A, Van Kooyk Y. DC-SIGN, a C-type lectin on dendritic cells that unveils many aspects of dendritic cell biology. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:921–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Svajger U, Anderluh M, Jeras M, Obermajer N. C-type lectin DC-SIGN: an adhesion, signalling and antigen-uptake molecule that guides dendritic cells in immunity. Cell Signal. 2010;22:1397–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geijtenbeek TB, Krooshoop DJ, Bleijs DA, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Grabovsky V, Alon R, Figdor CG, van Kooyk Y. DC-SIGN-ICAM-2 interaction mediates dendritic cell trafficking. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:353–357. doi: 10.1038/79815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geijtenbeek TB, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Adema GJ, van Kooyk Y, Figdor CG. Identification of DC-SIGN, a novel dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 receptor that supports primary immune responses. Cell. 2000;100:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engering A, Geijtenbeek TB, van Vliet SJ, Wijers M, van Liempt E, Demaurex N, Lanzavecchia A, Fransen J, Figdor CG, Piguet V, van Kooyk Y. The dendritic cell-specific adhesion receptor DC-SIGN internalizes antigen for presentation to T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:2118–2126. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geijtenbeek TB, Kwon DS, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Middel J, Cornelissen IL, Nottet HS, KewalRamani VN, Littman DR, Figdor CG, van Kooyk Y. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell. 2000;100:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon DS, Gregorio G, Bitton N, Hendrickson WA, Littman DR. DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of HIV is required for trans-enhancement of T cell infection. Immunity. 2002;16:135–144. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geijtenbeek TB, Van Vliet SJ, Koppel EA, Sanchez-Hernandez M, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Appelmelk B, Van Kooyk Y. Mycobacteria target DC-SIGN to suppress dendritic cell function. J Exp Med. 2003;197:7–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell DA, Fadden AJ, Drickamer K. A novel mechanism of carbohydrate recognition by the C-type lectins DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. Subunit organization and binding to multivalent ligands. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:28939–28945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104565200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiessling LL, Gestwicki JE, Strong LE. Synthetic multivalent ligands in the exploration of cell-surface interactions. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2000;4:696–703. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feinberg H, Castelli R, Drickamer K, Seeberger PH, Weis WI. Multiple modes of binding enhance the affinity of DC-SIGN for high mannose N-linked glycans found on viral glycoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4202–4209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609689200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becer CR, Gibson MI, Geng J, Ilyas R, Wallis R, Mitchell DA, Haddleton DM. High-affinity glycopolymer binding to human DC-SIGN and disruption of DC-SIGN interactions with HIV envelope glycoprotein. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15130–15132. doi: 10.1021/ja1056714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez-Avila O, Hijazi K, Marradi M, Clavel C, Campion C, Kelly C, Penades S. Gold manno-glyconanoparticles: multivalent systems to block HIV-1 gp120 binding to the lectin DC-SIGN. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:9874–9888. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasala F, Arce E, Otero JR, Rojo J, Delgado R. Mannosyl glycodendritic structure inhibits DC-SIGN-mediated Ebola virus infection in cis and in trans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3970–3972. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3970-3972.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang SK, Liang PH, Astronomo RD, Hsu TL, Hsieh SL, Burton DR, Wong CH. Targeting the carbohydrates on HIV-1: Interaction of oligomannose dendrons with human monoclonal antibody 2G12 and DC-SIGN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3690–3695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712326105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borrok MJ, Kiessling LL. Non-carbohydrate inhibitors of the lectin DC-SIGN. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12780–12785. doi: 10.1021/ja072944v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mangold SL, Prost LR, Kiessling LL. Quinoxalinone inhibitors of the lectin DC-SIGN. Chemical Science. 2012;3:772–777. doi: 10.1039/c2sc00767c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garber KC, Wangkanont K, Carlson EE, Kiessling LL. A general glycomimetic strategy yields non-carbohydrate inhibitors of DC-SIGN. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010;46:6747–6749. doi: 10.1039/c0cc00830c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reina JJ, Sattin S, Invernizzi D, Mari S, Martinez-Prats L, Tabarani G, Fieschi F, Delgado R, Nieto PM, Rojo J, Bernardi A. 1,2-Mannobioside mimic: synthesis, DC-SIGN interaction by NMR and docking, and antiviral activity. ChemMedChem. 2007;2:1030–1036. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sattin S, Daghetti A, Thepaut M, Berzi A, Sanchez-Navarro M, Tabarani G, Rojo J, Fieschi F, Clerici M, Bernardi A. Inhibition of DC-SIGN-mediated HIV infection by a linear trimannoside mimic in a tetravalent presentation. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:301–312. doi: 10.1021/cb900216e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Timpano G, Tabarani G, Anderluh M, Invernizzi D, Vasile F, Potenza D, Nieto PM, Rojo J, Fieschi F, Bernardi A. Synthesis of novel DC-SIGN ligands with an alpha-fucosylamide anchor. Chembiochem. 2008;9:1921–1930. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guzzi C, Angulo J, Doro F, Reina JJ, Thepaut M, Fieschi F, Bernardi A, Rojo J, Nieto PM. Insights into molecular recognition of Lewis(X) mimics by DC-SIGN using NMR and molecular modelling. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:7705–7712. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05938f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernardi A, Cheshev P. Interfering with the sugar code: design and synthesis of oligosaccharide mimics. Chemistry. 2008;14:7434–7441. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuster MC, Mann DA, Buchholz TJ, Johnson KM, Thomas WD, Kiessling LL. Parallel synthesis of glycomimetic libraries: targeting a C-type lectin. Org Lett. 2003;5:1407–1410. doi: 10.1021/ol0340383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grim JC, Garber KC, Kiessling LL. Glycomimetic building blocks: a divergent synthesis of epimers of shikimic acid. Org Lett. 2011;13:3790–3793. doi: 10.1021/ol201252x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roldos V, Canada FJ, Jimenez-Barbero J. Carbohydrate-protein interactions: a 3D view by NMR. Chembiochem. 2011;12:990–1005. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feinberg H, Mitchell DA, Drickamer K, Weis WI. Structural basis for selective recognition of oligosaccharides by DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. Science. 2001;294:2163–2166. doi: 10.1126/science.1066371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu L, Martin TD, Carrington M, KewalRamani VN. Raji B cells, misidentified as THP-1 cells, stimulate DC-SIGN-mediated HIV transmission. Virology. 2004;318:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.den Dunnen J, Gringhuis SI, Geijtenbeek TB. Innate signaling by the C-type lectin DC-SIGN dictates immune responses. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:1149–1157. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0615-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bergman MP, Engering A, Smits HH, van Vliet SJ, van Bodegraven AA, Wirth HP, Kapsenberg ML, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, van Kooyk Y, Appelmelk BJ. Helicobacter pylori modulates the T helper cell 1/T helper cell 2 balance through phase-variable interaction between lipopolysaccharide and DC-SIGN. J Exp Med. 2004;200:979–990. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smits HH, Engering A, van der Kleij D, de Jong EC, Schipper K, van Capel TM, Zaat BA, Yazdanbakhsh M, Wierenga EA, van Kooyk Y, Kapsenberg ML. Selective probiotic bacteria induce IL-10-producing regulatory T cells in vitro by modulating dendritic cell function through dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1260–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steeghs L, van Vliet SJ, Uronen-Hansson H, van Mourik A, Engering A, Sanchez-Hernandez M, Klein N, Callard R, van Putten JP, van der Ley P, van Kooyk Y, van de Winkel JG. Neisseria meningitidis expressing lgtB lipopolysaccharide targets DC-SIGN and modulates dendritic cell function. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:316–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anthony RM, Wermeling F, Ravetch JV. Novel roles for the IgG Fc glycan. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1253:170–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anthony RM, Kobayashi T, Wermeling F, Ravetch JV. Intravenous gammaglobulin suppresses inflammation through a novel T(H)2 pathway. Nature. 2011;475:110–113. doi: 10.1038/nature10134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gringhuis SI, den Dunnen J, Litjens M, van Het Hof B, van Kooyk Y, Geijtenbeek TB. C-type lectin DC-SIGN modulates Toll-like receptor signaling via Raf-1 kinase-dependent acetylation of transcription factor NF-kappaB. Immunity. 2007;26:605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Numazaki M, Kato C, Kawauchi Y, Kajiwara T, Ishii M, Kojima N. Cross-linking of SIGNR1 activates JNK and induces TNF-alpha production in RAW264.7 cells that express SIGNR1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;386:202–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pathak SK, Skold AE, Mohanram V, Persson C, Johansson U, Spetz A-L. Activated Apoptotic Cells Induce Dendritic Cell Maturation via Engagement of Toll-like Receptor 4 (TLR4), Dendritic Cell-specific Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 3 (ICAM-3)grabbing Nonintegrin (DC-SIGN), and beta 2 Integrins. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:13731–13742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.336545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.