Abstract

The sale and consumption of illicit tobacco increases consumption, impacts public health, reduces tax revenue and provides an argument against tax increases. Thailand has some of the best tobacco control policies in Southeast Asia with one of the highest tobacco tax rates, but illicit trade has the potential to undermine these policies and needs investigating. Two approaches were used to assess illicit trade between 1991 and 2006: method 1, comparison of tobacco used based on tobacco taxes paid and survey data, and method 2, discrepancies between export data from countries exporting tobacco to Thailand and Thai official data regarding imports. A three year average was used to smooth differences due to lags between exports and imports. For 1991–2006, the estimated manufactured cigarette consumption from survey data was considerably lower than sales tax paid, so method 1 did not provide evidence of cigarette tax avoidance. Using method 2 the trade difference between reported imports and exports, indicates 10% of cigarettes consumed in Thailand (242 million packs per year) between 2004 and 2006 were illicit. The loss of revenue amounted to 4,508 million Baht (2002 prices) in the same year, that was 14% of the total cigarette tax revenue. Cigarette excise tax rates had a negative relationship with consumption trends but no relation with the level of illicit trade. There is a need for improved policies against smuggling to combat the rise in illicit tobacco consumption. Regional coordination and implementation of protocols on illicit trade would help reduce incentives for illegal tax avoidance.

Keywords: cigarette, tax avoidance, illicit trade, illegal consumption

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) has ranked the global tobacco epidemic as a top priority for public health and has urged political leaders to take action to reverse the preventable epidemic of tobacco related health problems. Thailand’s tobacco control policies (some of the strongest in Southeast Asia) were examined using the “SimSmoke” simulation model, which showed that during 1991–2006, the prevalence of smoking decreased to 25% below the level it would have been without the policies. Tax increases and advertising bans had the largest impact (Levy et al, 2008). However, consumption has risen recently and public health benefits and revenue are lost if smokers purchase cheap illicit cigarettes (Cantreill et al, 2008).

The ceiling for cigarette tax was increased from 80% to 90% in 2009, with cigarette tax now 85% of the factory price (about two-thirds the retail price, Excise Department 2009). Tobacco companies opposed the increases, arguing higher taxes were an incentive for smuggling. Others have argued smuggling is unrelated to tobacco tax rates (Joossens and Raw, 1995). This paper estimates cigarette tax avoidance in Thailand by quantifying the magnitude of illicit cigarette use and the loss of government revenues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We estimated the illicit cigarette trade in Thailand using official data sources and two methodologies based on Merriman et al (2000).

Method 1

Merriman et al (2000) suggested cigarette taxes paid provide a useful method for measuring legal tobacco consumption and for modeling and estimating smuggling. The difference between cigarettes consumed based on taxes paid for tobacco (official legal consumption) and consumption obtained from survey data (what smokers say they smoke) is identified as illicit trade.

Legal consumption of cigarettes determined by taxes paid for both domestic and imported cigarettes was estimated. These tax data were assumed to be the most objective estimate of legal cigarette consumption. Duty-free sales, most of which from non-residents were excluded. The percent of estimated cigarettes consumed was reduced by 1%, to account for damage or product loss.

The prevalence of tobacco consumption was obtained from the National Health and Welfare Surveys (HWS) for 1991, 1996, 1999, and 2006, and the Cigarette Smoking and Alcoholic Drinking Behavior Survey (CSADBS) for the years 2001 and 2004 conducted by the National Statistical Office (NSO, 2007) and were used to estimate total annual tobacco consumption (what smokers say they smoke). Data regarding average daily cigarette consumption was obtained from the Situation of Tobacco Consumption among the Thai Population for 1991–2006 conducted by the Tobacco Control Research and Knowledge Management Center (Benjakul et al, 2008).

Estimation of cigarettes consumed

Only manufactured cigarettes were included in the analysis of legal cigarette consumption. Other types of tobacco are taxed at a very low rate or not at all. In order to estimate the annual manufactured cigarette consumption, we estimated the proportion of tobacco consumed as roll-your-own (RYO) and other types of tobacco, and subtracted this from the estimate of the total annual tobacco consumed.

The types of cigarettes smoked as specified by current smokers were RYO comprised 49.5%, manufactured cigarettes comprised 49.1% and other tobacco products comprised 1.4%.

Method 2

This method assesses illegal trade by comparing the reported exports to a country with the reported imports by that country using international trade data from UN-Comtrade. Any discrepancy between recorded exports and imports is considered an estimate of illicit trade.

It was assumed errors in recording were small and time difference effects were smoothed out by using three year averages. Exports include not only legal cigarettes destined to be legally imported into Thailand but also illicit imports. Some discrepancies between recorded export data and recorded import data may have been caused by inaccurate reporting of import and export data. Legitimate adjustments were allowed for (usually by excluding imports from duty-free sales to travelers) and import data should be close to export data.

Discrepancies between import and export estimation

Data regarding exports of cigarettes to Thailand from all other countries during the years 1991–2006 were obtained from the United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database (United Nation Statistic Division, 2008). Data regarding Thailand’s reported imports of cigarettes from those countries during 1991–2006 were obtained from the Thai Customs Department. Discrepancies between exports and imports were calculated using a three-year moving averages estimate, and considered as an approximation of cigarette tax avoidance.

Cigarette tax in Thailand

Cigarette excise tax is levied on manufactured cigarettes for domestic sale, usually collected from the producer or wholesaler. In May 2009 the tax ceiling was set to 90% of the factory price; the current cigarette excise tax is 85% (about two- thirds the retail price). Other tobacco products such as shredded tobacco used to roll your own cigarettes, is set at 0.1% (Visarutwong et al, 2009). The cigarette excise tax has increased about every two years to improve public health and increase government revenue. Following the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) agreement, the tariff levied on cigarettes traded within Southeast Asia is 0%, and 60% for non-ASEAN countries (Sarntisart, 2006).

Domestic cigarette production and sales

The Thailand Tobacco Monopoly (TTM) produced 2,356 million packs of cigarettes in 1997 but the production of cigarette has remained fairly steady at 1,417 million packs of cigarettes beginning in 2006. Production is approximately equal to sales and more than 90% of the cigarettes produced by the TTM were for domestic sale (TTM, 1991–2006).

Imported cigarettes sales

Since 1991 foreign cigarettes have been allowed to enter Thailand according to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) decision (Vathesatogkit et al, 2000). There has also been an influx of legally imported cigarettes (Thailand Health Promotion Institute, 2002) which increased from 50 million packs in 1992 to 487 million packs in 2005. The increasing market share of imports (22% in 2005) is partly explained by the effect of the AFTA, following which the imported cigarette market share rose from 3% to 22% (TTM, 1991–2006; Excise Department, 1991–2006).

Cigarette consumption estimated from surveys

In 1991, 32% of the population aged 15 and over smoked daily or occasionally, this decreased to 22% by 2006. Smoking decreased from 12.4 cigarettes per day in 1991 to 8.9 in 2006.

The total annual tobacco consumption (including RYO) was 55 billion cigarettes in 1991 and 36 billion cigarettes in 2006. Between 1991 and 1996, the early period of opening the market to foreign tobacco, the number of manufactured cigarettes used by smokers increased about 22%. During the next few years, when Thailand faced an economic crisis, the consumption of manufactured cigarettes continually decreased. The total consumption steadily decreased to 862 million packs (165 packs per capita) in 2006 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tobacco consumption based on cigarette taxes and on survey data, 1991–2006.

| Year | Cigarettes consumed based on tax (millions of packs) | Cigarette consumption based on survey data (millions of packs) | Percent change in consumption by year | Difference in tax and survey estimates of cigarettes consumed (millions of packs) | Net difference as percent of legal sales |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 1,935 | 1,313 | - | 622 | 32% |

| 1996 | 2,440 | 1,600 | 21.9 | 840 | 34% |

| 1999 | 1,790 | 1,263 | −21.1 | 528 | 29% |

| 2001 | 1,713 | 1,101 | −12.8 | 612 | 36% |

| 2004 | 2,115 | 972 | −11.7 | 1,143 | 54% |

| 2006 | 1,801 | 862 | −11.3 | 938 | 52% |

| Average | 1,966 | 1,185 | 781 | 40% |

RESULTS

Method 1

The difference between manufactured cigarette consumption obtained from surveys, and taxes paid, should provide evidence of cigarette tax avoidance, assuming no underreporting, and the surveys represented the whole population of Thailand.

In our analysis, the difference between sales data and consumption estimates was the opposite of what was expected because the taxes paid were considerably higher than estimated consumption based on surveys, by an average of 781 million packs or 40% of the legal sales. We cannot conclude there were no illegal cigarettes consumed in Thailand during the period of study, since this may be concealed by underreporting or other problems that prevent an accurate estimate of manufactured cigarette consumption based on survey data. This anomalous result may be explained by underreporting the prevalence and intensity of smoking in the survey data. In our analysis it was necessary to make a number of assumptions regarding manufactured and RYO cigarettes, which may have introduced inaccuracies in the share of RYO smokers. There are several other possible causes of the low estimate of consumption. The surveys of cigarette consumption did not include migrant workers, tourists to Thailand and populations of countries adjacent to Thailand. These people consumed legal cigarettes but this data was not included in the survey, resulting in an underestimation of cigarette consumption. It is also possible there may have been hoarding of tobacco prior to taxes increases, in order to maximize the profit of the tobacco company. These factors could account for some year-to-year differences, but not the overall trend. Thailand is an unlikely source of smuggled taxed cigarettes to neighboring countries, since Thailand has relatively higher prices than neighboring countries. These results suggest Method 1 was not a good approach for Thailand due to the shortcomings of the surveys. We were unable to conclude with this method what the level of illicit tobacco use was.

Method 2

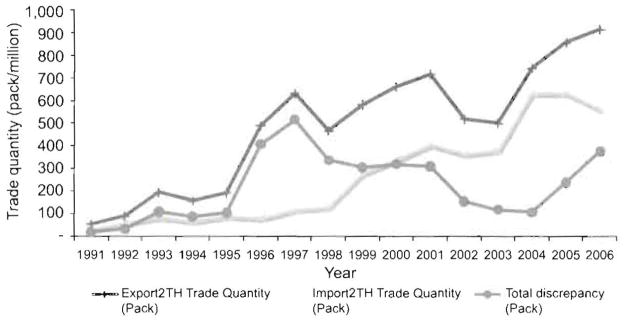

Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia and the USA are the top five cigarette exporters to Thailand, followed by Germany, Hong Kong, China, the UK and Japan. Most of the import/ export discrepancy is accounted for by trade with Indonesia. Table 2 and Fig 1 show the import/export data from 1991 to 2006, with recorded imports consistently lower than recorded exports. In 2006, 39% of exports to Thailand were missing. This huge amount of missing exported cigarettes represents 19% of legal sales for that year, which could be sold illegally in Thailand or in other countries. A shortfall peak occurred in 1997 during the economic crisis. It implies that during that period there was illicit cigarette trade between others countries and Thailand. During the economic crisis the Thai Baht was devalued (2 July 1997). The exchange rate went from 25.09 in 1994 to 47.24 in 1997 (Chainuvati et al, 1999). This had an effect on the cost of imported goods to Thailand, affecting the local demand for foreign cigarettes. This may have led to increased illicit trade to avoid taxation and reduce transaction costs.

Table 2.

Discrepancies in cigarettes between exports to Thailand and imports into Thailand, 1991–2006.

| Year | Exports to Thailand (millions of packs) | Imports into Thailand (millions of packs) | Trade discrepancy (millions of packs) | Percent difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 53.01 | 31.85 | 21.16 | 40 |

| 1992 | 89.06 | 60.00 | 29.06 | 33 |

| 1993 | 194.13 | 85.06 | 109.06 | 56 |

| 1994 | 155.69 | 66.69 | 89.00 | 57 |

| 1995 | 192.91 | 87.40 | 105.51 | 55 |

| 1996 | 488.61 | 81.26 | 407.35 | 83 |

| 1997 | 631.64 | 117.28 | 514.36 | 81 |

| 1998 | 466.31 | 129.26 | 337.05 | 72 |

| 1999 | 581.78 | 277.15 | 304.63 | 52 |

| 2000 | 660.53 | 341.38 | 319.15 | 48 |

| 2001 | 715.79 | 406.42 | 309.37 | 43 |

| 2002 | 518.60 | 363.07 | 155.53 | 30 |

| 2003 | 499.06 | 379.85 | 119.21 | 24 |

| 2004 | 742.87 | 634.14 | 108.73 | 15 |

| 2005 | 855.60 | 634.28 | 221.33 | 26 |

| 2006 | 914.43 | 559.83 | 354.60 | 39 |

Fig 1.

Exports, imports and discrepancies in cigarettes trade during 1991–2006 (millions of packs).

Sources: UN-Statistic Division, 2008; Thai Customs Department, 1991–2006.

Estimation of smuggling using method 2

To allow for the lags and short term variations in trade, three year averages of discrepancies between exports and imports were used (Table 3). Assuming these cigarettes were consumed within Thailand, they are approximate estimates of cigarette smuggling into Thailand. The total consumption of cigarettes in Thailand would be the sum of smuggled cigarettes and legal taxed cigarettes. Our estimates suggest the level of smuggling rose from 3% in the early 1990s to a peak of 17% in 1998, then declined to 7% by 2004 and rose to 10% in 2005. This smuggling represents a loss of revenue to the government.

Table 3.

Smuggling and total consumption of manufactured cigarettes obtained from export and import discrepancies (method 2) 1991–2006.

| Year | Taxed cigarettes (millions of packs) | Trade Discrepancy (smuggled cigarettes) (millions of packs) | Three year average of smuggled cigarettes (millions of packs) | Total estimated consumption =Taxed cigarettes + smuggled cigarettes (millions of packs) | Smuggled cigarettes as percent of total estimated consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 1,935 | 21.16 | |||

| 1992 | 2,013 | 29.06 | 53.09 | 2,066 | 2.6 |

| 1993 | 2,103 | 109.06 | 75.71 | 2,178 | 3.5 |

| 1994 | 2,302 | 89.00 | 101.19 | 2,403 | 4.2 |

| 1995 | 2,150 | 105.51 | 200.62 | 2,351 | 8.5 |

| 1996 | 2,440 | 407.35 | 342.40 | 2,782 | 12.3 |

| 1997 | 2,392 | 514.36 | 419.59 | 2,811 | 14.9 |

| 1998 | 1,907 | 337.05 | 385.35 | 2,292 | 16.8 |

| 1999 | 1,790 | 304.63 | 320.28 | 2,110 | 15.2 |

| 2000 | 1,805 | 319.15 | 311.10 | 2,116 | 14.7 |

| 2001 | 1,713 | 309.51 | 261.40 | 1,974 | 13.2 |

| 2002 | 1,729 | 155.53 | 194.75 | 1,923 | 10.1 |

| 2003 | 1,886 | 119.21 | 127.82 | 2,014 | 6.3 |

| 2004 | 2,115 | 108.73 | 149.76 | 2,265 | 6.9 |

| 2005 | 2,176 | 221.33 | 228.22 | 2,404 | 10.0 |

| 2006 | 1,801 | 354.60 |

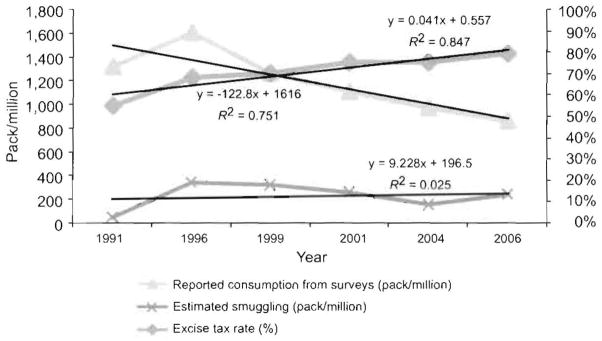

Excise tax rates and consumption

The trends in consumption and in excise tax rates are shown in Fig 2, which shows evidence of a negative relationship. No relationship was found between the level of illegal cigarette use during 1991–2006 and the excise tax rate. The trend of estimated smuggling varied slightly with increases in illicit cigarette use over time while excise tax continually increased with time.

Fig 2.

The relationship between taxation, consumption and smuggling over the years 1991–2006.

Sources: NSO, 2007; TTM, 1991–2006; Excise Department, 1995–2001; Tax rate adopted from Vitsarutwong (2009).

Government tax revenue

Total real revenues (in 2002 values) from legal cigarette consumption are given in Table 4. The value of tax revenue lost from illegal sales was estimated by multiplying the estimated smuggled cigarettes by the average tax per pack. The percent tax revenue lost by tax avoidance (smuggling) varied from 1% in 1991 to 18% in 1999 and was 14% in 2006.

Table 4.

Total real revenue from taxed cigarette consumption and revenue loss from smuggling (Baht in 2002), 1991–2006.

| Year | Total real revenue from taxed cigarette sales(million Baht) | Average tax per pack (Baht) | Estimated smuggling (millions of packs) | Revenue loss from smuggling (million Bath) | Revenue loss as percent of total revenue from taxed cigarette sales |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 29,856 | 15.37 | 21 | 323 | 1.10% |

| 1996 | 36,823 | 14.94 | 342 | 5,109 | 13.90% |

| 1999 | 29,160 | 16.11 | 320 | 5,155 | 17.70% |

| 2001 | 31,386 | 17.7 | 261 | 4,620 | 14.70% |

| 2004 | 35,554 | 16.64 | 156 | 2,596 | 7.30% |

| 2006 | 32,757 | 18.63 | 242 | 4,508 | 13.80% |

Source: Real tax revenue data from Excise Department, Ministry of Finance, 1991–2006

DISCUSSION

There is no direct method to estimate the magnitude of illegal cigarette consumption or smuggling. The two methods employed in this study are empirical estimations based on available data from national surveys on smoking behavior and international trade data. In Method 1 taxed cigarette consumption greatly exceeded estimated consumption based on survey data. Underreporting of both prevalence and intensity of smoking was a common finding in survey data, particularly where there is strong health promotion about smoking. A similar finding was reported by Stehr (2005) for the US, where between 1985 and 2001 manufactured cigarette consumption, estimated from survey data, was 55% lower than legal sales data. His explanation was a high level of underreporting in an environment of health promotion, similar to our findings.

In method 2, the analysis of cigarette tax avoidance using UN-Comtrade data from multiple countries revealed a large gap between records of exports to Thailand and Thai official records of imports, which is suggestive of smuggling. This discrepancy ranged from 15% to 83% of recorded exports to Thailand during 1991–2006. These results suggest tax avoidance on foreign cigarettes exported to Thailand by multinational companies. In a NSO survey in 2007, 19% of smokers in Thailand consumed internationally manufactured cigarettes with no label warnings. It is generally accepted unlabelled cigarettes are illegal. The discrepancy between exports and imports may also be due to other factors, such as valuation of CIF (cost, insurance, and freight) and FOB (Free on board) and time lags in reporting (United Nations Statistics Division, 2008). Exports to Thailand include contraband, bypassing Customs in order to illegally import cigarettes into Thailand, or re-exporting illegal cigarettes to other countries.

Our results show a high cigarette tax did not appear to be related to the level of cigarette smuggling in Thailand. These results have limitations due to the difficulty in estimating illicit trade. Other methods are needed to confirm these results. Further study is needed regarding the smoking behavior surveys used in order to account for the large gap between cigarette consumption and taxed cigarette sales. Regional coordination could help reduce incentives for cigarette smuggling.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Grant Number R01TW007924 from the Fogarty International Centre (FIC) and National Cancer Institute (NCI) at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and co-funding from the Tobacco Control Research and Knowledge Management Center (TRC), Mahidol University. The study could not has been completed without the information obtained from the National Statistical Office, Excise Department, Custom Department and Thailand Tobacco Monopoly and also the support of the Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA), the review committee from Duke University, the American Cancer Society.

References

- Benjakul S, Kengkarnpanich M, Temsirikul L, et al. Situation of tobacco consumption of the Thai population in 1991–2006. Bangkok: Tobacco Control Research and Knowledge Management Center, Mahidol University, Thailand; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cantreill J, Hung D, Fahs MC, et al. Purchasing patterns and smoking behaviors after a large tobacco tax increase: a study of Chinese Americans living in New York City. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:135–46. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chainuvati N, Nakavachara V, Na Ayudhya K. Thailand:an economic evaluation. 1999 [Cited 2009 May 7], Available from: URL: http://wwwpersonal.umich.edu/~kathrynd/Thailand.542.pdf.

- Excise Department, Thailand. Annual report. Bangkok: Excise Department; 1991–2006. [Google Scholar]

- Joossens L, Raw M. Smuggling and cross border shopping of tobacco in Europe. BMJ. 1995;310:1393–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6991.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DT, Benjakul S, Ross H, et al. The role of tobacco control policies in reducing smoking and deaths in a middle income nation: results from the Thailand SimSmoke simulation model. Tob Control. 2008;17:53–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.022319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriman D, Yurekli A, Chaloupka FJ. How big is the worldwide cigarette smuggling problem? Tobacco control in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 365–92. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office (NSO) The cigarette smoking and alcoholic drinking behavior survey. Bangkok: Ministry of Information and Communication Technology; 2007. [Cited 2009 May 15]. Available from:URL: http://servicenso.go.th/nso/nso_center/project/table/files/S-smoking/2550/000/00_S-smoking_2550_000_020000_03100.xls. [Google Scholar]

- Stehr M. Cigarette tax avoidance and evasion. J Health Econ. 2005;24:277–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarntisart I. ASEAN regional summary report: AFTA and tobacco. Bangkok: Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thailand Health Promotion Institute (THPI) Tobacco economics. Bangkok: The National Health Foundation; 2002. pp. 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Thailand Tobacco Monopoly (TTM) TTM annual report. Bangkok: TTM; 1991–2006. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Statistics Division. Commodity Trade Statistics Database (COMTRADE) New York: UN Statistics Division; 2008. [Cited 2008 Aug 7]. Available from: URL: http://comtrade.un.org/db. [Google Scholar]

- Vathesatogkit P, Hughes G, Ritthiphakdee B. Thailand: winning battles, but the war’s far from over. Tob Control. 2000;9:122–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visarutwong C, Sirirungruangamorn S, Temsirikulchai L, et al. Tobacco law. Bangkok: Tobacco Control Research and Knowledge Management Center; 2009. p. 32. [Google Scholar]