Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) has long been recognized as a toxic molecule in biological systems. However, emerging studies now link controlled fluxes of this reactive sulfur species to cellular regulation and signaling events akin to other small molecule messengers, such as nitric oxide, hydrogen peroxide, and carbon monoxide. Progress in the development of fluorescent small-molecule indicators with high selectivity for hydrogen sulfide offers a promising approach for studying its production, trafficking, and downstream physiological and/or pathological effects.

Introduction

For centuries, hydrogen sulfide (H2S) has been viewed primarily as a noxious chemical species that is naturally produced by geological and microbial activities [1]. Exposure to this colorless, flammable gas, which gives rotten eggs their distinctive odor, can trigger eye and respiratory tract irritation [2]. Inhalation of excess H2S can result in loss of consciousness, respiratory failure, cardiac arrest, and, in extreme cases, death [3]. On the other hand, more recent studies have challenged this traditional view of H2S as a toxin and have shown that mammals can also produce H2S in a controlled fashion [4], suggesting that this reactive sulfur species is important in maintaining normal physiology [5]. H2S may arise from non-enzymatic processes, including release from sulfur stores and metabolism of polysulfides [6,7]. In mammalian systems, H2S may also be produced by two pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzymes, cystathionine gamma lyase (CSE) and cystathionine beta synthase (CBS), as well as cysteine aminotransferase and mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (CAT/MST). These enzymes catalyze an assortment of reactions that produce H2S from sulfur-containing biomolecules such as cysteine and homocysteine (Fig. 1a) [8,9]. The presence of these enzymes in human tissues ranging from the heart and vasculature [10,11], brain [12,13,14], kidney [15], liver [16], lungs [17,18], and pancreas [19] presages widespread physiological roles for H2S in the body (Fig. 1b). Moreover, a variety of disease phenotypes have been linked to inadequate levels of H2S, including Alzheimer’s disease [20], impaired cognitive ability in CBS-deficient patients [21], and hypertension in CSE knockout mice [22]; excessive H2S production in vital organs may be responsible for the pathogenesis of other diseases such as diabetes [23,24,25]. These seminal studies have patently established H2S as an essential physiological mediator and cellular signaling species [26,27], but our understanding of H2S chemistry and its far-ranging contributions to physiology and pathology is still in its infancy.

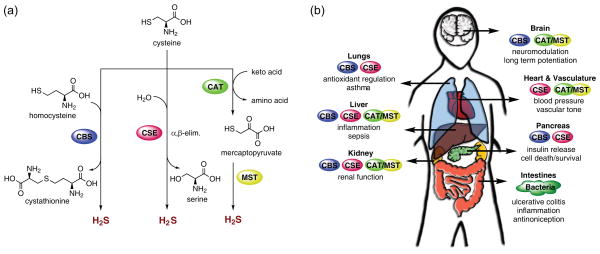

Figure 1.

Biology of H2S in the human body. (a) Selected major biochemical pathways for H2S production. Two PLP-dependent enzymes, cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), are found in the cytoplasm and synthesize H2S. Biochemical studies show that CBS primarily catalyzes the formation of cystathionine from homocysteine and cysteine, whereas CSE facilitates the α,β-elimination of cysteine by water, producing serine and H2S. Two additional enzymes located in the cytoplasm and mitochondria, cysteine aminotransferase (CAT) and mercaptopyruvate sulfur transferase (MST), have also been identified as sources of H2S. CAT acts upon keto acids and cysteine to yield mercaptopyruvate, from which H2S is released by MST. (b) Selected physiological effects and biological roles of H2S in the human body and enzymes responsible for H2S production in various tissue types.

The complex biological roles of H2S and potential therapeutic implications provide compelling motivation for devising new ways to monitor its production, trafficking, and consumption in living cells, tissues, and whole organisms. Traditional methods for H2S detection [28], including colorimetric assays [29,30], polarographic sensors [31], and gas chromatography [32,33], typically result in sample destruction and/or are limited to extracellular detection. As such, fluorescent molecular probes offer an appealing approach for the detection of H2S and other reactive small molecules because of their cell permeability and high sensitivity. A key challenge for selective detection of H2S within the cellular milieu is the comparatively high concentrations of biological sulfur species such as glutathione as well as cysteine residues. In this review we provide a brief survey of recent chemical strategies for fluorescence detection and imaging of H2S in biological systems (Table 1) [34].

Table 1.

Summary of fluorescent H2S probes.

| Azide-based | λex (nm) | λem (nm) | Detection limit | Response in vitro |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF1 | 490 | 525 | 5–10 μM | 7-fold turn on after 60 min at 25 °Ca (10 μM probe, 100 μM NaHS, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) |

| SF2 | 492 | 525 | 5–10 μM | 9-fold turn-on after 60 min at 25 °Ca (10 μM probe, 100 μM NaHS, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) |

| DNS-Az | 340 | 535 | 1 μM | 40-fold turn-on after 3 min (30 μM probe, 30 μM NaHS, 20 mM PBS, 0.5% Tween-20, pH 7.5) |

| Cy-N3 | 625 | 710 (–N3) 750 (–NH2) |

0.08 μM | F750nm/F710nm = 0.6 before reaction to 2.0 after complete conversion to amine after 20 min at 37 °C (10 μM probe, 100 μM NaHS, 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) |

| HSN2 | 432 | 542 | 1–5 μM | 60-fold turn-on after 45 min at 37 °C (5 μM probe, 500 μM NaHS, 50 mM PIPES, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.4) |

| cpGFP- Tyr66pAzF | 480 | 510 | 10 μM | 1.7-fold turn-on after 15 min at RT (5 μM probe with 50 μM NaHS, PBS, pH = 7.4) |

| FS1 | 363 | 548 | 5–10 μM | 21-fold TPEF enhancement after 120 min at 37 °C (5 μM probe, 100 μM Na2S, 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.2) |

| H2S trapping | λex (nm) | λem (nm) | Detection limit | Response in vitro |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFP1 | 300 | 388 | -- | >10-fold turn-on after 60 min at 37 °C (10 μM probe, 50 μM Na2S, 9:1 10 mM PBS:CH3CN, pH 7.4) |

| SFP2 | 465 | 510 | 5 μM | >13-fold turn-on after 60 min at 37 °Ca (5 μM probe, 50 μM Na2S, 20 mM PBS, pH 7.0) |

| Xian et al. Probe 1 | 465 | 515 | 1–10 μM | 55–70-fold turn-on after 60 min at 25 °C (100 μM probe, 50 μM NaHS, 9:1 PBS:CH3CN, pH 7.4) |

| Xian et al. Probe 5 | 476 | 513 | 1 μM | 11-fold turn-on after 30 min at 25 °C (5 μM probe, 100 μM NaHS, 10 mM PBS, pH 7.4) |

| Xian et al. Probe 6 | 476 | 513 | 1 μM | 160-fold turn-on after 30 min at 25 °C (5 μM probe, 100 μM NaHS, 10 mM PBS, pH 7.4) |

| CuS precipitation | λex (nm) | λem (nm) | Detection limit | Response in vitro |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSip-1 | 491 | 516 | 10 μM | 50-fold turn on immediately at 37 °C (1 μM probe, 10 μM NaHS, 30 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) |

| L1Cu | 495 | 534 | ~5 μM | >4-fold turn-on immediately (20 μM probe, 40 μM S2−, 1:1 PBS:CH3CN v/v, pH 7.2) |

| L1Cu′ | 494 | 523 | 1.7 μM | 25–30-fold turn-on after 1 min at RT (10 μM probe, 20 μM H2S, 6:4 HEPES:CH3CN v/v, pH 7.0) |

Reaction not complete at indicated time.

H2S-mediated reduction of azides to amines

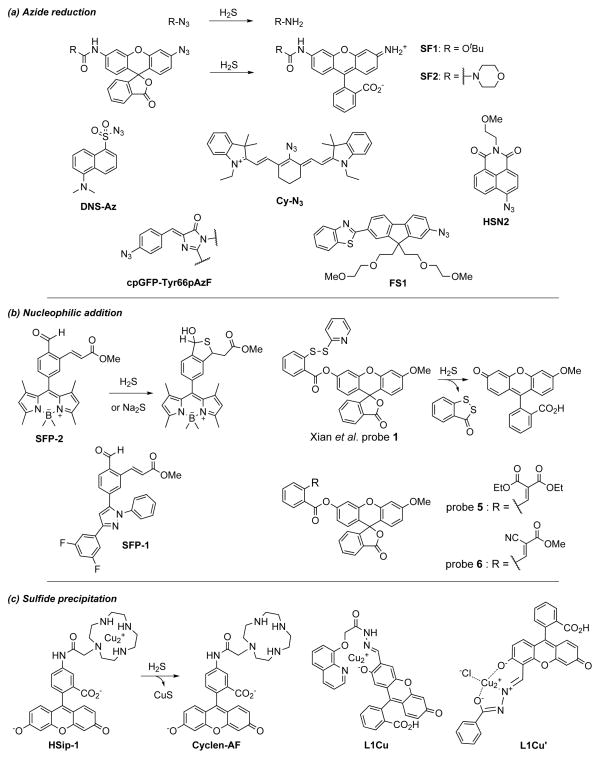

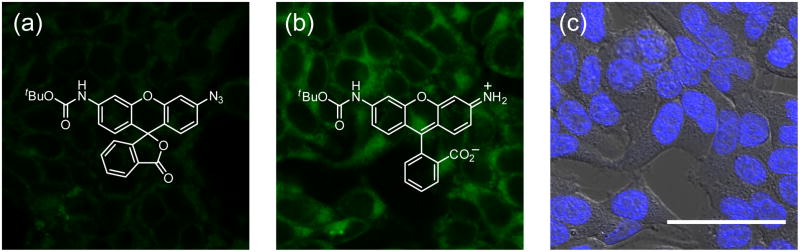

To expand our laboratory’s program in the area of redox biology, particularly on reaction-based detection methods for studying the chemistry and biology of the oxidative signaling molecule H2O2 via chemospecific boronate [35–45] and ketoacid [46] oxidations, we noted that the selective reduction of azides by H2S could provide amines under mild conditions [47,48] and sought to utilize this reaction-based switch as a new approach to molecular H2S probes. Specifically, we found that by masking a rhodamine with an azide functional group we could generate Sulfidefluor-1 (SF1) and Sulfidefluor-2 (SF2) probes that give fluorescent turn-on responses upon H2S-mediated reduction of the aryl azide to the corresponding aniline (Fig. 2a). These probes show high selectivity for H2S over a range of reactive sulfur species, including abundant cellular thiols such as glutathione and cysteine, as well as a host of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Moreover, these first-generation probes are capable of monitoring changes in H2S levels in living cells. Exogenous addition of micromolar NaHS produces a robust fluorescent response in HEK293T cells and related mammalian cell lines (Fig. 3) [49]. We have now developed a series of next generation of H2S probes that are capable of monitoring endogenous H2S fluxes and are actively pursuing biological studies in a variety of models. Concomitant to our work, Wang showed that nonfluorescent DNS-Az, a dansyl fluorophore modified with a sulfonyl azide, reacts rapidly with H2S concentrations as low as 1 μM in phosphate buffer, releasing strongly-fluorescent dansyl amide [50]. Upon ultraviolet excitation, DNS-Az can detect H2S concentrations from 5 to 100 μM in bovine serum, presaging that this promising platform and related motifs can be applied to bioanalytical assays.

Figure 2.

Selected molecular probes for the detection of hydrogen sulfide. (a) The H2S-mediated reduction of azides to amines has been applied to rhodamine (SF1 and SF2), dansyl (DNS-Az), cyanine (Cy-N3), 8-naphthalimide (HSN2), protein (cpGFP-Tyr66pAzF), and fluorene (FS1) scaffolds which display a range of fluorescent responses and sensitivities. (b) Attack of H2S at the aldehyde group and subsequent intramolecular Michael addition converts SFP-1 and SFP-2 to fluorescent dyes. Nucleophilic addition of H2S to Xian et al. probe 1 results in displacement of 2-thiopyridine and persulfide formation; intramolecular cyclization due to nucleophilic attack of the thiol on the ester group generates benzodithiolone and releases 3-O-methoxyfluorescein. Two probes containing benzylidienemalonate and cyanoacrylate as Michael acceptors (Xian et al. probe 5 and probe 6) react to trap H2S in a similar manner. (c) Reaction of H2S with Cu2+ precipitates copper sulfide from the weakly fluorescent copper complex HSip-1, releasing Cyclen-AF which exhibits enhanced fluorescent properties. L1Cu and L1Cu′ also produce a fluorescent turn-on response following CuS precipitation.

Figure 3.

Confocal microscopy images demonstrating detection of changes in H2S levels in living cells by SF1. (a) SF1 alone incubated in HEK293T cells. (b) Cells loaded with SF1 followed by incubation with NaHS. (c) Brightfield images of the field of cells in (b) overlaid with images of Hoescht stain at 37 °C. Scale bar represents 50 μm. Adapted with permission from the American Chemical Society. [49]

Shortly after our initial publication appeared, we were pleased to see that the concept of H2S-mediated reduction of azides to amines was extended to other fluorophore scaffolds by several laboratories (Fig. 2a), establishing the generality of this reaction-based switch for selective H2S detection. Han reported Cy-N3, an azido-heptamethine cyanine dye that functions as a unique ratiometric internal charge transfer (ICT) probe for H2S [51]. Cy-N3 displays a 40 nm red-shift in fluorescence emission wavelength upon azide reduction. With a detection limit of 80 nM H2S, Cy-N3 can respond to changes in H2S levels in RAW264.7 macrophages. To the best of our knowledge, this probe is the first ratiometric fluorescent indicator for H2S. Pluth reported a 4-azido-1,8-naphthalimide probe, Hydrosulfide Naphthalimide-2 (HSN2), along with a nitro analog, which can react selectively with H2S to give a turn-on response and can operate in living cells with good signal-to-noise ratios [52]. Recently, Ai and coworkers developed the first genetically-encoded H2S probe by substituting p-azidophenylalanine (pAzF) for Tyr66 in circularly-permuted green fluorescent protein (cpGFP) [53]. Conversion of the azide to the amine in cpGFP-Tyr66pAzF facilitates formation of the mature chromophore and elicits a fluorescent turn-on response. Finally, Cho and colleagues prepared the first two-photon H2S probe, featuring an azide-modified benzothiazole-fluorene that was used to image H2S in rat hippocampal slices at depths of 90–190 μm [54]. Taken together, this selection of probes illustrates the versatility of the azide functionality as an H2S trigger, and further elaborations of this strategy will allow modulation of emission colors, targetability, imaging modalities, and probe reactivity.

Trapping of H2S via nucleophilic addition

In parallel to the work on azide reduction strategies, several other reaction-based H2S probes detect the analyte by acting as electrophiles. Initial nucleophilic addition of H2S to the probe results in a thiol which performs a subsequent nucleophilic addition to a second electrophilic site and leads to cyclization to generate a fluorescent molecule (Fig. 2b). Using this general strategy, He, Jiao, and co-workers have designed elegant probes which position an aldehyde group ortho to an αβ, -unsaturated acrylate methyl ester on an aryl ring [55]. Following nucleophilic attack of H2S on the aldehyde functionality, the trapped thiol undergoes an intramolecular Michael addition to the unsaturated ester to produce a dihydrobenzothiophene derivative. While other thiols can reversibly add to the aldehyde, the resulting thioacetal product cannot perform a second nucleophilic addition, imparting the probe with selectivity for H2S. Two reagents—the blue-emitting SFP-1, based on a 1,3,5-triaryl-2-pyrazoline fluorophore, and SFP-2, based on a BODIPY dye—utilize this Michael addition trigger and displays selective reaction with H2S. SFP-2 exhibits a 13-fold increase in fluorescence intensity upon reaction with 50 μM Na2S and demonstrates fluorescent properties suitable for imaging in living cells, with a H2S detection range in cells from 0–200 μM.

Another clever probe by Xian’s laboratory employs a related strategy, using a disulfide and an ester group as the two electrophilic sites for reaction with H2S [56]. H2S displaces 2-thiopyridine, resulting in a persulfide where the terminal sulfur attacks the ester, cyclizing to form a benzodithiolone and simultaneously releasing methoxyfluorescein. The probe responds to 50–500 μM H2S in bovine plasma and 250 μM H2S in cells. This reagent demonstrates selectivity for H2S over other biological thiols in vitro, because displacement of the thiopyridine by a substituted thiol results in a mixed disulfide which does not undergo cyclization. Xian and coworkers reported two additional probes that feature benzylidienemalonate or cyanoacrylate moieties as sites for Michael addition; these probes also release methoxyfluorescein upon reaction with H2S [57].

Copper sulfide precipitation

The classic gravimetric precipitation of CuS from Cu2+ complexes has been successfully employed as a strategy to detect H2S by a fluorescence response (Fig. 2c). Nagano reported H2S imaging probe 1 (HSip-1), which consists of a cyclen macrocycle attached to fluorescein [58]. Binding of Cu2+ to the cyclen receptor quenches fluorescence. Upon reaction with a sulfide donor such as Na2S or NaHS, CuS precipitates and releases unbound cyclen-AF, which displays enhanced fluorescence. HSip-1 rapidly detects sulfide concentrations as low as 10 μM in vitro, and the membrane-permeable diacetate derivative can be loaded into cells to detect 100 μM changes in Na2S. Zeng and Bai have utilized a similar approach in the design of their L1 sulfide probe, which combines a fluorescein with a pendant 8-hydroxyquinoline ligand for copper binding [59]. Coordination of copper to L1 quenches fluorescence and produces a spectral shift when the probe is converted to the L1Cu metal complex. Addition of sulfide anion triggers precipitation of CuS and regeneration of L1, resulting in a fluorescent turn-on as well as a colorimetric change from pink to yellow in the presence of sulfide at 10–100 μM concentrations. Utilizing this strategy, Zeng and Bai prepared another copper-containing probe with a lower detection limit of 1.7 μM [60]. This L1Cu′ probe displays 25–30-fold fluorescence enhancement upon reaction with H2S. In these reports the authors have demonstrated that HSip-1 and L1Cu undergo CuS precipitation preferentially in the presence of sulfide (S2−) over other sulfur-containing compounds such as sulfates, biologically-relevant thiols, and selected reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen species. However, as alternative Cu2+ complexes may react with other sulfur species such as reduced glutathione [58], appropriate chelating groups must be screened and selectivity studies performed to confirm specific H2S detection.

Conclusions and outlook

The rapid development of several first-generation molecular H2S probes by a wide range of chemical approaches illustrates the promise for studying the roles of H2S in intact biological systems with unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution. As the field continues to advance and a wider series of H2S indicators become available, we can envision probes tailored for specific models of interest including cells, tissues, and whole organisms, allowing the elucidation of intricate and dynamic inter- and intracellular events involving H2S production or depletion. Further exploration of H2S biology in a variety of systems will undoubtedly reveal how this reactive sulfur species modulates cellular and physiological conditions, offering deeper insight into redox biology and the dynamic interplay that occurs between reductive and oxidative species in complex cellular and in vivo environments.

Highlights.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) can mediate physiology and disease pathology in mammalian systems.

The development of molecular probes for H2S detection allows H2S to be studied in intact cells, tissues, or whole organisms.

Current probes employ a variety of reaction-based strategies to achieve selectivity for H2S over other biological thiols.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM079465), the Packard Foundation, and Astra Zeneca, Amgen, and Novartis for funding our laboratory’s research in sulfur redox biology. CJC is an Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Guidotti TL. Hydrogen sulfide: advances in understanding human toxicity. Int J Toxicol. 2010;29:569–581. doi: 10.1177/1091581810384882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans CL. The toxicity of hydrogen sulfide and other sulfides. J Exp Physiol. 1967;52:231–248. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1967.sp001909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiffenstein JR, Hulbert WC, Roth SH. Toxicology of hydrogen sulfide. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1992;32:109–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.32.040192.000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamoun P. Endogenous production of hydrogen sulfide in mammals. Amino Acids. 2004;26:243–254. doi: 10.1007/s00726-004-0072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5*.Szabó C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:917–935. doi: 10.1038/nrd2425. This review addresses H2S biochemistry and role in disease, with a discussion of H2S-related therapeutics. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishigami M, Hiraki K, Umemura K, Ogasawara Y, Ishii K, Kimura H. A source of hydrogen sulfide and a mechanism of its release in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:205–14. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benavides GA, Squadrito GL, Mills RW, Patel HD, Isbell TS, Patel RP, Darley-Usmar VM, Doeller JE, Kraus DW. Hydrogen sulfide mediates the vasoactivity of garlic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17977–17982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705710104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8**.Singh S, Banerjee R. PLP-dependent H2S biogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814:1518–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.02.004. This review details the three major enzymatic pathways responsible for H2S production including substrates, structure, and regulation of CBS, CSE, and CAT/MST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh S, Padovani D, Leslie RA, Chiku T, Banerjee R. Relative contributions of cystathionine beta-synthase and gamma-cystathionase to H2S biogenesis via alternative trans-sulfuration reactions. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22457–22466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosoki R, Matsuki N, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous smooth muscle relaxant in synergy with nitric oxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:527–531. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calvert JW, Coetzee WA, Lefer DJ. Novel insights into hydrogen sulfide-mediated cytoprotection. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:1203–1217. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee M, Schwab C, Yu S, McGeer E, McGeer PL. Astrocytes produce the antiinflammatory and neuroprotective agent hydrogen sulfide. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1523–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shibuya N, Tanaka M, Yoshida M, Ogasawara Y, Togawa T, Ishii K, Kimura H. 3-Mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase produces hydrogen sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:703–714. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14*.Abe K, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1066–1071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01066.1996. The authors identified CBS as a major source of H2S in the brain and elucidated the effects of H2S on brain activity, particularly on long-term potentiation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tripatara P, Patel NSA, Brancaleone V, Renshaw D, Rocha R, Sepodes B, Mota-Filipe H, Perretti M, Thiemermann C. Characterisation of cystathionine gamma-lyase/hydrogen sulphide pathway in ischaemia/reperfusion injury of the mouse kidney: An in vivo study. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;606:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stipanuk MH, Beck PW. Characterization of the enzymic capacity for cysteine desulphhydration in liver and kidney of the rat. Biochem J. 1982;206:267–277. doi: 10.1042/bj2060267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang P, Zhang G, Wondimu T, Ross B, Wang R. Hydrogen sulfide and asthma. Exp Physiol. 2011;96:847–852. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.057448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madden JA, Ahlf SB, Dantuma MW, Olson K, Roerig DL. Precursors and inhibitors of hydrogen sulfide synthesis affect acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in the intact lung. J Appl Physiol. 2012;112:411–418. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01049.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhatia M, Wong FL, Fu D, Lau HY, Moochhala SM, Moore PK. Role of hydrogen sulfide in acute pancreatitis and associated lung injury. FASEB J. 2005;19:623–625. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3023fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eto K, Asada T, Arima K, Makifuchi T, Kimura H. Brain hydrogen sulfide is severely decreased in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293:1485–1488. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00422-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richard S, Beard RS, Jr, Bearden SE. Vascular complications of cystathionine β-synthase deficiency: future directions for homocysteine-to-hydrogen sulfide research. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H13–H26. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00598.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22**.Yang G, Wu L, Jiang B, Yang W, Qi J, Cao K, Meng Q, Mustafa AK, Mu W, Zhang S, Snyder SH, Wang R. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine γ-lyase. Science. 2008;322:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1162667. This study provides strong evidence for H2S as a physiological signaling molecule, as CSE knockout mice display elevated blood pressure. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaneko Y, Kimura Y, Kimura H, Niki I. L-Cysteine inhibits insulin release from the pancreatic β-cell: possible involvement of metabolic production of hydrogen sulfide, a novel gasotransmitter. Diabetes. 2006;55:1391–1397. doi: 10.2337/db05-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu L, Yang W, Jia X, Yang G, Duridanova D, Cao K, Wang R. Pancreatic islet overproduction of H2S and suppressed insulin release in Zucker diabetic rats. Lab Invest. 2009;89:59–67. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng X, Chen Y, Zhao J, Tang C, Jiang Z, Geng B. Hydrogen sulfide from adipose tissue is a novel insulin resistance regulator. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;380:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krishnan N, Fu C, Pappin DJ, Tonks NK. PTP1B and its role in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra86. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li L, Rose P, Moore PK. Hydrogen sulfide and cell signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:169–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28*.Tangerman A. Measurement and biological significance of the volatile sulfur compounds hydrogen sulfide, methanethiol and dimethyl sulfide in various biological matrices. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877:3366–3377. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.05.026. This review provides a survey of qualitative and quantitative H2S detection by traditional methods. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siegel LM. A direct microdetermination for sulfide. Anal Biochem. 1965;11:126–132. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(65)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer E. Formation of methylene blue in response to hydrogen sulfide. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1883;16:2234–2236. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doeller JE, Isbell TS, Benavides G, Koenitzer J, Patel H, Patel RP, Lancaster JR, Jr, Darley-Usmar VM, Kraus DW. Polarographic measurement of hydrogen sulfide production and consumption by mammalian tissues. Anal Biochem. 2005;341:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hannestad U, Margheri S, Sörbo B. A sensitive gas chromatographic method for determination of protein-associated sulfur. Anal Biochem. 1989;178:394–398. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90659-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furne J, Saeed A, Levitt MD. Whole tissue hydrogen sulfide concentrations are orders of magnitude lower than presently accepted values. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:1479–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90566.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.For a recent review on H2S detection. Xuan W, Sheng C, Cao Y, He W, Wang W. Fluorescent probes for the detection of hydrogen sulfide in biological systems. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:2282–2284. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107025.

- 35.Miller EW, Chang CJ. Fluorescent probes for nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide in cell signaling. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:620–625. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36*.Lippert AR, Van de Bittner GC, Chang CJ. Boronate oxidation as a bioorthogonal reaction approach for studying the chemistry of hydrogen peroxide in living systems. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:793–804. doi: 10.1021/ar200126t. This review illustrates how reaction-based approaches can be applied to chemoselective bioimaging, using the boronate-mediated oxidation of hydrogen peroxide as a general example. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang MCY, Pralle A, Isacoff EY, Chang CJ. A selective, cell-permeable optical probefor hydrogen peroxide in living cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15392–15393. doi: 10.1021/ja0441716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller EW, Tulyathan O, Isacoff EY, Chang CJ. Molecular imaging of hydrogen peroxide produced for cell signaling. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:263–267. doi: 10.1038/nchembio871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srikun D, Miller EW, Domaille DW, Chang CJ. An ICT-based approach to ratiometric fluorescence imaging of hydrogen peroxide produced in living cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4596–4597. doi: 10.1021/ja711480f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dickinson BC, Chang CJ. A targetable fluorescent probe for imaging hydrogen peroxide in the mitochondria of living cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9638–9639. doi: 10.1021/ja802355u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller EW, Dickinson BC, Chang CJ. Aquaporin-3 mediates hydrogen peroxide uptake to regulate downstream intracellular signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15681–15686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005776107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Srikun D, Albers AE, Nam CI, Iavarone AT, Chang CJ. Organelle-targetable fluorescent probes for imaging hydrogen peroxide in living cells via SNAP-tag protein labeling. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4455–4465. doi: 10.1021/ja100117u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van de Bittner GC, Dubikovskaya EA, Bertozzi CR, Chang CJ. In vivo imaging of hydrogen peroxide production in a murine tumor model with a chemoselective bioluminescent reporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21316–21321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012864107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dickinson BC, Peltier J, Stone D, Schaffer DV, Chang CJ. Nox2 redox signaling maintains essential cell populations in the brain. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:106–112. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srikun D, Albers AE, Chang CJ. A dendrimer-based platform for simultaneous dual fluorescence imaging of hydrogen peroxide and pH gradients produced in living cells. Chem Sci. 2011;2:1156–1165. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lippert AR, Keshari KR, Kurhanewicz J, Chang CJ. A hydrogen peroxide-responsive hyperpolarized 13C MRI contrast agent. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3776–3779. doi: 10.1021/ja111589a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gronowitz S, Westerlund C, Hörnfeldt A-B. The synthetic utility of heteroaromatic azido compounds. I. Preparation and reduction of some 3-azido-2-substituted furans, thiophenes, and selenophenes. Acta Chem Scand, Sect B. 1975;29:224–232. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pang L-J, Wang D, Zhou J, Zhang L-H, Ye X-S. Synthesis of enamine-derived pseudodisaccharides by stereo- and regio-selective functional group transformations. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:4252–4266. doi: 10.1039/b907518f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49**.Lippert AR, New EJ, Chang CJ. Reaction-based fluorescent probes for selective imaging of hydrogen sulfide in living cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:10078–10080. doi: 10.1021/ja203661j. SF1 and SF2 establish azide reduction as a novel strategy for chemospecific H2S detection and are the first reported examples of molecular probes that can be used to image H2S in living cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50**.Peng H, Cheng Y, Dai C, King AL, Predmore BL, Lefer DJ, Wang B. A fluorescent probe for fast and quantitative detection of hydrogen sulfide in blood. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:9672–9675. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104236. DNS-Az shows that sulfonyl azide reduction can be used to detect H2S and can operate in biological fluids. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu F, Li P, Song P, Wang B, Zhao J, Han K. An ICT-based strategy to a colorimetric and ratiometric fluorescence probe for hydrogen sulfide in living cells. Chem Commun. 2012;48:2852–2854. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17658k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Montoya LA, Pluth M. Selective turn-on fluorescent probes for imaging hydrogen sulfide in living cells. Chem Commun. 2012;48:4767–4769. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30730h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53**.Chen S, Chen Z-J, Ren W, Ai H-W. Reaction-based genetically encoded fluorescent hydrogen sulfide sensors. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:9589–9592. doi: 10.1021/ja303261d. This first example of a genetically-encoded H2S probe incorporates an azide-substituted unnatural amino acid into green fluorescent protein to render the protein chromophore sensitive to H2S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Das SK, Lim CS, Yang SY, Han JH, Cho BR. A small molecule two-photon probe or hydrogen sulfide in live tissues. Chem Commun. 2012 doi: 10.1039/c2cc33909a. Advance Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55**.Qian Y, Karpus J, Kabil O, Zhang S-Y, Zhu H-L, Banerjee R, Zhao J, He C. Selective fluorescent probes for live-cell monitoring of sulphide. Nat Commun. 2011:2–495. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1506. 10.1038. SFP-1 and SFP-2 establish that tandem nucleophilic and Michael additions of H2S can be employed for its selective detection in living cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56**.Liu C, Pan J, Li S, Zhao Y, Wu LY, Berkman CE, Whorton AR, Xian M. Capture and visualization of hydrogen sulfide by a fluorescent probe. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:10327–10329. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104305. This mixed disulfide probe employs a clever nucleophilic addition and cyclization sequence to detect H2S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xian M. Reaction based fluorescent probes for hydrogen sulfide. Org Lett. 2012;14:2184–2187. doi: 10.1021/ol3008183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58**.Sasakura K, Hanaoka K, Shibuya N, Mikami Y, Kimura Y, Komatsu T, Ueno T, Terai T, Kimura H, Nagano T. Development of a highly selective fluorescence probe for hydrogen sulfide. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:18003–18005. doi: 10.1021/ja207851s. HSip-1 shows that selective CuS precipitation can be used to detect H2S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hou F, Huang L, Xi P, Cheng J, Zhao X, Xie G, Shi Y, Cheng F, Yao X, Bai D, Zeng Z. A retrievable and highly selective fluorescent probe for monitoring sulfide and imaging in living cells. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:2454–2460. doi: 10.1021/ic2024082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hou F, Cheng J, Xi P, Chen F, Huang L, Xie G, Shi Y, Liu H, Bai D, Zeng Z. Recognition of copper and hydrogen sulfide in vitro utilizing a fluorescein derivatives indicator. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:5799–5804. doi: 10.1039/c2dt12462a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]