ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Patients are vulnerable to poor quality, fragmented care as they transition from hospital to home. Few studies examine the discharge process from the perspectives of multiple healthcare professionals.

OBJECTIVE

To understand care transitions from the perspective of diverse healthcare professionals, and identify recommendations for process improvement.

DESIGN

Cross sectional qualitative study.

PARTICIPANTS AND SETTING

Clinicians, care teams, and administrators from the inpatient general medicine services at one urban, academic hospital; two outpatient primary care clinics; and one Medicaid managed care plan.

APPROACH

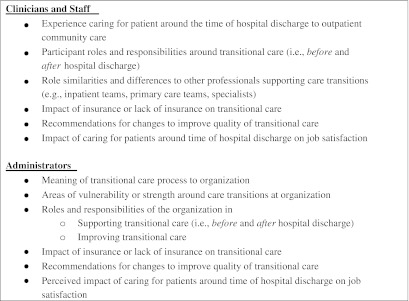

We conducted 13 focus groups and two in-depth interviews with participants prior to initiating a hospital-funded, multi-component transitional care intervention for uninsured and low-income publicly insured patients, the Care Transitions Innovation (C-TraIn). We used thematic analysis to identify emergent themes and a cross-case comparative analysis to describe variation by participant role and setting.

KEY RESULTS

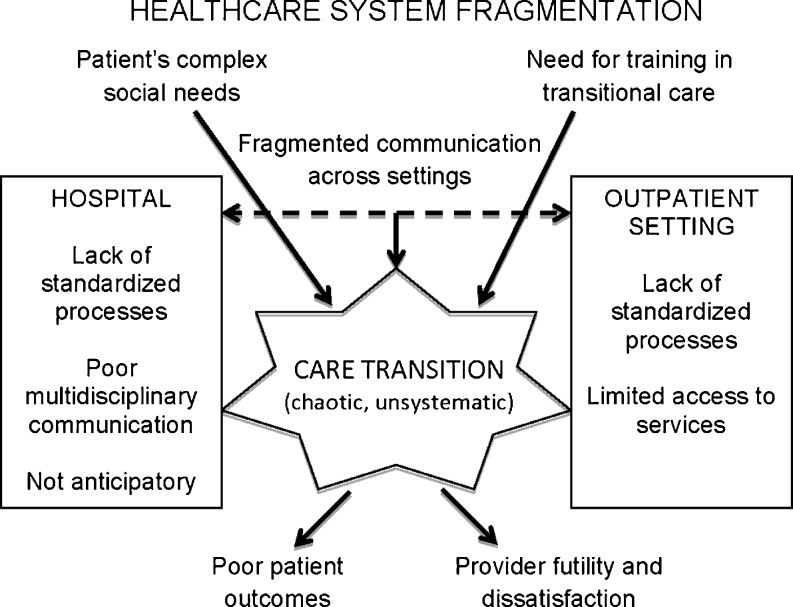

Poor transitional care reflected healthcare system fragmentation, limiting the ability of healthcare professionals to provide optimal patient care. Lack of standardized processes, poor multidisciplinary communication within the hospital, and fragmented communication across settings led to chaotic, unsystematic transitions, poor patient outcomes, and feelings of futility and dissatisfaction among providers. Patients with complex psychosocial needs were especially vulnerable during care transitions. Recommended changes to improve transitional care included improving hospital multidisciplinary hospital rounds, clarifying accountability as patients move across settings, standardizing discharge processes, and providing additional medical staff training.

CONCLUSIONS

Hospital to home care transitions are critical junctures that can impact health outcomes, experience of care, and costs. Transitional care quality improvement initiatives must address system fragmentation, reduce communication barriers within and between settings, and ensure adequate professional training.

KEY WORDS: transition and discharge planning, continuity of care, communication, quality improvement

BACKGROUND

During the hospital to home transition, patients are at high risk for adverse drug events, incomplete or inaccurate information transfer, preventable hospital readmission, and even death.1–5 Patients indicate this transition is fraught with uncertainty and difficulty accessing outpatient care.6 With growth of the hospitalist movement, patients are often the only thread linking inpatient and outpatient settings.7 Moreover, patients encounter multiple providers, including nurses, pharmacists, physicians, and case managers within each setting. Ideally, team members work together across and within settings to achieve the triple aim of reduced costs, improved quality, and enhanced patient experience.8

Care transition redesign efforts are underway,9–12 yet existing studies tend to focus on specific age ranges or diagnoses,13 and limited research describes diverse provider views or needs unique to economically vulnerable patients. We undertook this qualitative study to evaluate how health professionals across the care continuum perceive: 1) key barriers to effective hospital to home care transitions, 2) the responsibilities of different care providers during transitions of care, and 3) recommendations for systems improvements. Understanding these perceptions may inform the design of better-integrated health systems, a critical need given national policies focused on reducing readmissions.14,15

METHODS

Setting and Study Design

In this cross-sectional qualitative study, we conducted interviews just prior to implementation of the Care Transitions Innovation (C-TraIn), a multi-component transitional care program for uninsured and low-income publicly insured adult medical patients at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU).16 OHSU is an urban, academic medical center in Portland, Oregon where 15 % of general medicine patients are uninsured and 19 % have Medicaid.17 The Portland area safety-net, which includes 14 clinics, has limited capacity for uncompensated care and many uninsured and Medicaid patients have difficulty establishing primary care. We invited OHSU hospital departments and C-TraIn partner sites to participate, including one academic internal medicine clinic, a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), and one Medicaid Managed care plan. Two authors (HE, DK) used findings to inform continuous quality improvement.

Sampling Strategy

To enhance relevance to improvements, we worked with C-TraIn site leadership to identify a purposive sample of healthcare professionals and administrators meeting the following inclusion criteria: (a) provision of care or management of services around time of hospital discharge, and (b) willingness to meet with the study team. No participants were excluded. We conducted separate focus groups with each organization. To understand distinct perspectives, we grouped participants from the academic medical center by role (e.g., inpatient attending physicians, residents, case management). Groups frequently included peers who work together and program supervisors were often present. We conducted individual interviews in cases where multiple participants could not attend the focus groups. Sampling proceeded iteratively, with analysis of each session informing and refining the interview guide. We collected data until we reached saturation, the point at which findings repeat or recur, over the sample as a whole.18,19 We did not aim to reach saturation within each distinct participant group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Roles, Training, and Setting (Inpatient Versus Outpatient)

| Organization | Participant roles | Training (n) | Patient care setting | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD | RN or LPN | RPH or PharmD | Other | In | Out | Both | |||

| Focus Group (N = 13) | |||||||||

| 1 | OHSU | Hospitalist Physicians | 3 | 3 | |||||

| 2 | OHSU | Inpatient Teaching Attendings | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 3–5a | OHSU | Inpatient Nursing | 11 | 11 | |||||

| 6 | OHSU | Resident Physicians | 6 | 6 | |||||

| 7 | OHSU | Medical Subspecialists | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| 8 | OHSU | Internal Medicine Clinic Attendings | 5 | 3 | 2 | ||||

| 9 | Old Town Clinic | Clinic Staff | 2 | 2 | 5† | 7 | 2 | ||

| 10 | OHSU | Pharmacists | 5 | 4 | 1 | ||||

| 11 | OHSU | Inpatient Case Managers | 4 | 4 | |||||

| 12 | CareOregon | Managed Care Plan Employees | 5 | 2 | 3‡ | N/A | |||

| 13 | OHSU | Administrators | 2 | 3 | 10§ | N/A | |||

| Interviews (N = 2) | |||||||||

| 1 | OHSU | Medical Subspecialist | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2 | OHSU | Social Worker | 1‖ | 1 | |||||

OHSU = Oregon Health & Science University; Old Town Clinic = A Federally Qualified Health Center; CareOregon = A Medicaid Managed Care Plan

aThree separate sessions were held with inpatient nursing teams

Other Training: † 1 Medical Assistant, 2 Occupational Therapists, 2 Other PCP (1 Physician Assistant, 1 Naturopathic Doctor); ‡ 1 MSW, 1 Pharmacy Technician, 1 Health Care Guide; § 7 MBA/MHA/MS, 3 Bachelors; ‖ 1 MSW

Data Collection

The first author (MMD), a social-developmental psychologist with expertise in qualitative research and quality improvement, conducted all sessions using a semi-structured guide (see Text Box). The analysis team critiqued each interview, particularly early in data collection, to identify biases and areas warranting additional inquiry.

We conducted 13 focus groups and two in-depth interviews with 75 health care professionals and administrators from September 30, 2010 to January 13, 2011. Participants provided informed consent and completed a demographic intake survey at each session. Sessions were audio recorded, lasting 41 min on average (range: 19–58 min), and a research assistant took field notes to capture non-verbal communication. Recordings were transcribed, de-identified, and transferred to Atlas.ti (Version 5.2, Berlin) for data analysis and retrieval. The OHSU Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Data Analysis

The multidisciplinary team used the six phases of thematic analysis to identify emergent themes. This includes familiarizing with data; generating initial codes; searching for, reviewing, then defining and naming themes; and producing a scholarly report.20 We used an inductive approach, at a semantic level, to ground findings in participant statements. Four authors (MMD, MD, HE, DK) read transcripts and defined a preliminary coding scheme. Using an iterative process, we independently coded transcripts; small groups then met to discuss codes, identify emergent themes, and resolve discrepancies through consensus.21 One author (MD) participated in all small-group coding meetings. Another author (CN) helped refine themes during multiple half-day retreats with the full analysis team. We conducted a cross-case comparative analysis by participant role and setting to examine differences among perspectives.22 Although we conducted one focus group with some disciplines (e.g., residents, hospital administration), we reviewed dominant concerns within role categories for illustrative purposes. The senior author (HE) used member checking with C-TraIn participants and at national conferences to finalize themes.

RESULTS

Participant professional roles, training, and setting are summarized in the Table 1. Thirty three percent of participants represented inpatient (n = 25), 17 % outpatient (n = 13), and 16 % spanned both settings (n = 12). Remaining participants represented OHSU administrators (n = 15, 20 %) and managed care health plan employees (n = 10, 13 %). Mean age was 42 years and 31 % were males. Figure 1 depicts participants’ perspectives on transitional care.

Figure 1.

Healthcare professional views of hospital to home care transitions.

Transitional Care Gaps Reflect Broader Health System Fragmentation

Many participants viewed poor transitional care as one element of a broken healthcare system. A hospital administrator stated,

"…The focus on transitions is one of the many fires burning…when we can think and lead holistically, and focus on the design of the [entire] system, then it will help to solve some of these chronic nagging components, which [are] hard fixing in isolation. We could put band-aids on them, but they end up being expensive, ineffective band-aids with all the other problems at the core of the system."

Participants indicated that misaligned financial incentives and inadequate compensation for care coordination exacerbated gaps. One Internal Medicine Clinic physician commented, “If I do the work [visiting a hospitalized patient to coordinate care], then I feel angry that I’m not getting paid for it. If I don’t do the work, I feel like I’m not giving the care. So either way you go there’s a real down side.”

Some thought that without system-level changes, individual efforts to improve the quality of transitional care would be ineffective. For example, inpatient providers acknowledged the futility of providing high acuity hospital care without necessary follow-up. One resident physician commented, “I felt ridiculous that we could provide intensive [hospital] care…[but we] couldn’t provide any of the outpatient care… I felt like I was not treating the patient correctly."

Patients’ Complex Psychosocial Needs and Limited Access to Outpatient Resources Present Barriers

Participants considered transitions risky for all patients, but acknowledged that factors such as lack of insurance, unstable housing, poor social support, and mental illness increased risk. One pharmacist described, “We just assume everybody can pay for their meds, or everybody has insurance. And if they don’t, …there’s nobody following up on the other side.”

Although many physicians stated they treated patients equally regardless of insurance status, some used the inpatient setting to mitigate social and financial disparities by delaying discharge or performing outpatient tests. One medical subspecialist stated, “Anything that’s not acutely addressed during hospitalization is subject to being foiled by lack of insurance.” Conversely, some inpatient physicians and nurses described an underlying tension between the hospital’s role in providing acute care, and its role as the ultimate safety net for those lacking outpatient resources.

"…If [inpatients] are not acutely ill, the assumption is that they or their families need to figure out a way to get the medications they need, to get them transport from the hospital, and to get them follow up care… That’s not our job. Our job is to care for people who are acutely ill." [Inpatient Nurse]

Lack of patient motivation compounded socioeconomic barriers and was frustrating to some participants. One inpatient nurse described, “We have frequent fliers—they lack the motivation to take care of themselves or they lack resources… We’re gonna send them out on the street and those people likely will come back in.”

Lack of Standardized Processes Contributed to Inefficiencies and Chaos

Participants described transitions as ‘chaotic’, ‘unsystematic’, and unstandardized. Organizational responsibilities during these transitions are not clearly defined. A hospital administrator and former clinician said,

"We don’t have a community contract where everybody acknowledges their role… ‘my role as the sender is to do these things’, ‘my role as the recipient is to do these things’…the ‘who will’ and ‘how’ of the handoff. We never get close to that sort of formality, which is really what any smart handoff or transition would require."

Inpatient participants thought frequent rotation amongst attendings and residents—some who work in the hospital only a few weeks per year—magnified the need for standardization. One inpatient case manager commented, “[A new attending] can totally change the whole plan of care.” Lack of standardization contributed to inefficient use of inpatient provider time, specifically when physicians needed to secure outpatient follow-up appointments or perform other administrative tasks. A resident physician stated, “…Anyone can make an appointment, it doesn’t have to be someone with an MD.” Participants suggested that using a systematic peri-discharge checklist and consistent templates for the discharge summary could improve standardization and identify accountability across the multidisciplinary team.

Poor Multidisciplinary Communication Within the Hospital Makes it Difficult to Effectively Perform Peri-Discharge Tasks

Many inpatient participants expressed frustration with poor multidisciplinary communication, believing that it contributed to inefficient discharges and role confusion. Pharmacists, nurses, and other staff described being left out of decision-making by inpatient physicians who act as ‘solo pioneers.’ Lack of timely communication impeded the ability to effectively execute transitional care tasks as highlighted in the following exchange between inpatient nurses in one focus group:

RN1: "In terms of discharge, we walk into the room and the patient says, ‘I’m going.’ And we’re like [inhales deeply] ‘It would’ve been nice if someone would have told us!’" [others make agreement sounds in background.]

RN3: "Yeah. Or when they say that they’re getting discharged and then they actually don’t get discharged, who’s the bad guy and who has to go tell ’em that…‘You’ve got to stay another day.’…or…‘You’re getting discharged to the streets.’"

Communication failures can result in critical medication errors. An inpatient pharmacist described a patient who was sent home without needed anticoagulation, “It was clearly defined in my note…[but] because…they don’t notify us we don’t have that opportunity to look at what they’re actually saying [to the patient at discharge].”

Many participants noted that some efforts to improve systems, like the electronic medical record, have had unintended negative consequences on interpersonal communication. One inpatient nurse noted, “[the discharge] can happen without us ever actually speaking to doctors, it all happens through the computer.” When asked how to improve communication around discharge, many, including inpatient attending and resident physicians, pharmacists, subspecialists, nursing, case management, and social work staff, suggested multidisciplinary meetings. Some participants noted that informal relationships may reduce communication barriers within and across settings.

Communication Across Settings is Fragmented, Which can Lead to Poor Patient Outcomes and Affect Clinician Job Satisfaction

Although all participant groups identified poor cross-site communication as a major gap, it was especially troubling to primary care providers (PCPs).

"…A patient’s there in front of me [after discharge], they’ve had a life changing event, and I’m sitting there without the information. You feel like an idiot…I would think, ‘What kind of system do you guys have here? I almost died, and you don’t even have the information….’ That’s embarrassing and I don’t think it engenders a lot of confidence for your patients." [Old Town Clinic PCP]

PCPs relied on discharge summaries, which are often absent, incomplete, or difficult to read. Inpatient and outpatient participants acknowledged that communication gaps can lead to bad outcomes, allowing important details to “just sort of fall into the ether.” Providers attributed a wide range of adverse events to poor communication. For example, a PCP explained,

"…At my old practice I never got discharge summaries… I thought I had known what had gone on in the hospital, but there had been an incidental finding on [the patient’s] CAT scan… and I never knew about it because I never got the discharge summary…. He had liver cancer and died… It was just the saddest that that's ever happened."

A shift toward hospitalist care and a lack of interoperability between electronic medical records exacerbate communication gaps, which are further compounded by pressure from the health system to discharge patients earlier. Another PCP described,

"The package that leaves the hospital now…more often than historically, includes a PICC (peripherally inserted central catheter) line, Foley catheter, oxygen—without a plan for when those are to be stopped and without communication to anyone about who’s in charge next. Sometimes [patients] come back to see us months after they’ve been discharged—they’ve been wearing a Foley catheter all that time!"

PCPs indicated they could provide helpful information for hospital admission and discharge. Inpatient physicians described uncertainty regarding when and how to engage PCPs. Alhough there was a desire for more communication, variation in work schedules, preferred methods of exchange (phone versus electronic), and variable patient acuity made this difficult.

A Need Exists for More Training Around Transitional Care

Many participants articulated the need for more formal training around care transitions. A resident physician commented,

"[Clinicians are] well trained to be effective diagnosticians…we’re not really educated on how to do the [care transition] process effectively…every time it happens we’re sort of reinventing the wheel…and the people that you’re learning from may not know how to do it appropriately either."

Another resident described knowledge and skill uncertainties around discharge,

"You’re on the [cardiac care unit]…sending someone home on sternal precautions, but what are sternal precautions?… Or when should they get follow up? Two weeks, a week? …Was there any evidence base guiding any of those decisions? It’s like ‘oh, God, you kicked them out, and hope everything works.’"

Lack of anticipatory planning hinders quality transitions, and could be a training target. One inpatient attending physician described, “[Like] pneumonia or cellulitis, discharge planning needs to be on the active problem list. Then at discharge you’ve been planning well in advance, and don’t just say…‘let’s scribble some prescriptions and write a discharge order…’”

On-the-job training was also important to nurses, pharmacists, case managers, and physicians. An inpatient attending physician stated, “Unfortunately, you sort of have to experience the quality of a bad discharge to know what’s important.” Experience in multiple settings informed competent transitional care delivery. An inpatient case manager explained, “I understand how complex the different environments can be…my past experience as a nurse in a skilled nursing facility and home health helps the transitions go much smoother.”

Providers Experienced Poor Quality Transitions as Painful And Dissatisfying

System frustrations felt personal to some. One Inpatient Teaching Attending commented, “Very rarely I’ve had a great day because that discharge went smoothly…that’s not really on my list of what made my day great. What made my day horrible is that the discharge went poorly.”

Providers often viewed discharge as a capstone and marker for overall quality of hospitalization. However, participants had to reconcile the level of care they wanted to provide with what was feasible within the system.

"[At discharge I wonder]… am I ripping the safety net out from under my patients?…did I do the process as best as I could—or as best as the system would let me… to make this the last stay in the hospital and prevent the readmission? Prevent adverse outcomes?….[long pause] It was a set-up for things to fall through the cracks." [Inpatient Teaching Attending]

Themes Were More Concordant than Discordant Across Groups, Though Dominant Suggestions for Improvement Were Closely Associated with Participant Roles

For example, floor nurses emphasized their role in providing patient education, which they cannot do without advanced knowledge of the discharge plan. Inpatient physicians and case managers expressed frustration with lack of outpatient resources—particularly amongst socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. Resident physicians focused on training gaps and performing tasks below their license. In-patient and outpatient pharmacists felt underutilized, suggesting greater involvement in medication reconciliation, discharge protocols requiring pharmacy consult, and funding to support service expansion.

Clinicians and staff at both outpatient sites focused on communication, emphasizing the tension between their potential to contribute to transitional care planning and the barriers preventing coordinated care between settings. Hospital administrators focused on systems, identifying lack of clarity in organizational responsibilities, and acknowledging their role in facilitating community-wide conversations to improve transitions.

DISCUSSION

Our multidisciplinary participants identified major challenges in providing optimal care transitions. Although system fragmentation, particularly for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients, was viewed as the root of transitional care gaps, many identified key targets for improvement, including improving multidisciplinary communication and enhancing process standardization. Our work substantiates prior research, indicating that barriers to effective transitional care occur at the delivery system, but also at the clinician and patient levels.23 Although costs of poor transitional care are understood at patient and system levels,5,6,24 we add to the literature by showing that transitional care gaps and lack of agency to improve them profoundly affects multidisciplinary provider job satisfaction.

Few qualitative studies explore provider perceptions and needs around care transitions,25–27 and we are unaware of any that explore views across disciplines and settings. Inclusion of multidisciplinary, cross-continuum perspectives facilitates an understanding of the breadth of process changes and stakeholder engagement necessary to effect improvements. Redesign efforts focused on a single provider group or a limited part of the transition might have limited impact. Indeed, though a variety of transitional care interventions have been studied, the vast majority have not demonstrated reductions in readmission rates.28 Successful interventions have focused on bridging inpatient and outpatient settings and improving cross-site communication, but these interventions focused on patient level healthcare delivery and did not examine ways to integrate multidisciplinary care roles within and across settings.9,10,12

Emergent themes in our study parallel many of the cultural and structural tenets of the patient-centered medical home, including creating multidisciplinary teams, promoting interdisciplinary communication, working to the “top of the license,” tailoring care to the needs of each patient, and working for payment reform.29,30 Results also support the need for process standardization. As suggested by participants and as adopted by some broad scale redesign efforts, this could include standard discharge checklists and cross-site coordination.11 Efforts to implement multidisciplinary rounds that support anticipatory planning in some inpatient settings are currently underway.11,31

Although improving communication across settings was clearly indicated as a way to improve transitional care, there may be disagreements about how and when communication should occur, based on individual preferences. This underscores the need for community-wide discussions to explicitly identify expectations. This process could lead to a ‘community contract’ specifying inpatient and outpatient responsibilities for each transitional care element. In addition to system and community level processes, redesign efforts should incorporate patient engagement, as earlier interventions have done.9,10,12

Participants strongly emphasized the need to provide care transition training. Although the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) recently developed educational milestones that encompass transitions of care,32 few institutions have implemented curricula at the post-graduate level.33–36 Similar to the need to identify transitional care standards, it may be useful to develop core competencies to guide training, continuing medical education, and curriculum development. For example, there could be enhanced education to teach providers: what post-discharge needs to anticipate for different patient groups; knowledge of specific red flags to highlight for patients; how to facilitate multidisciplinary team work and cross-site communication; and recognition of social determinants of health that might impact a patient’s ability to self-manage illness during times of transition.

Because we designed our study to inform local continuous quality improvement, this could limit generalizability of findings. However, we think stakeholder engagement is an important step for improvement. Our goal was to achieve saturation across the sample as a whole and not within distinct participant groups. Although participants were heterogeneous in some settings (e.g., CareOregon, Old Town Clinic), limiting our ability to attribute perceptions by professional training (e.g., physician, nursing), we highlight key concerns within training categories and roles. Additional research exploring the challenges faced by specific professions may be warranted. Further, supervisors attended some focus groups, and although we encouraged participants to share openly, this may have limited participants’ commentary. Finally, although the analysis team possessed inpatient and outpatient experience, four members are physicians and we may have benefitted from including ancillary staff. Member checks indicated that our themes were not biased based on this composition. Despite these limitations, our findings shed important light into the varied perspectives that influence care transitions. They can inform transitional care improvements within and across hospital and outpatient settings.

CONCLUSION

Our multi-stakeholder study highlights transitional care gaps across and within settings. Participants identify numerous opportunities for improvement, including improving multidisciplinary and cross-site communication, standardizing processes, increasing accountability for the elements of effective transitions, and enhancing training around transitional care.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

We would like to thank the providers and administrative staff who participated in this research and who continue to support implementation of the Care Transitions Innovation (C-TraIn). We are also grateful to Sonya Howk, MPA:HA and Dora Raymaker, MS for their assistance with data collection.

Funders

Funding for this project is provided by Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Portland, OR and by a Clinical and Translational Science Award to OHSU (National Institute of Health/National Center for Research Resources grant No. 1 UL1 RR024140 01).

Prior Presentations

Presented in part at the 34th annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, Phoenix, Arizona, May 4–7, 2011 and the Academy for Healthcare Improvement, Arlington, VA, May 7–8, 2012.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. Can Med Assoc J. 2004;170(3):345–349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):646–651. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman EA, Mahoney E, Parry C. Assessing the quality of preparation for posthospital care from the patient’s perspective: the care transitions measure. Med Care. 2005;43(3):246–255. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuo Y-F, Sharma G, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102–1112. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27(3):759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):675–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Society, of Hospital Medicine. Project BOOST: Better Outcomes for Older adults through Safe Transitions. Society of Hospital Medicine, Philadelphia, PA. 2012. Available at: www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost. Accessed June 22 2012.

- 12.Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178–187. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raven MC, Billings JC, Goldfrank LR, Manheimer ED, Gourevitch MN. Medicaid patients at high risk for frequent hospital admission: real-time identification and remediable risks. J Urban Health. 2009;86(2):230–241. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9336-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Compilation of Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: as Amended Through 1 November 2010, Including Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act health-related portions of the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minott J. Reducing Hospital Readmissions. Washington: Academy Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Englander H, Kansagara D. Planning and designing the Care Transitions Innovation (C-TraIn) for uninsured and Medicaid patients. J Hosp Med. 2012. doi:10.1002/jhm.1926. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Administrative Data 2009, 2010. Portland: Oregon Health & Science University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF. Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: controversies and recommendations. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):331–339. doi: 10.1370/afm.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuzel A. Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan S, VanWynsberghe R. Cultivating the Under-Mined: Cross-Case Analysis as Knowledge Mobilization. Forum: Qualitative Social Research; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):549–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Committee, on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute, of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century: The National Academies Press; 2001.

- 25.Rydeman I, Törnkvist L. The patient’s vulnerability, dependence and exposed situation in the discharge process: experiences of district nurses, geriatric nurses and social workers. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(10):1299–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eija G, Marja-Leena P. Home care personnel’s perspectives on successful discharge of elderly clients from hospital to home setting. Scand J Caring Sci. 2005;19(3):288–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foust JB, Vuckovic N, Henriquez E. Hospital to home health care transition: patient, caregiver, and clinician perspectives. West J Nurs Res. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM. The patient-centered medical home. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2038–2040. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American, Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), American, Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American, College of Physicians (ACP), American, Osteopathic Association (AOA). Joint Principles of the Patient Centered Medical Home. 2007. Available at: http://www.pcpcc.net/content/joint-principles-patient-centered-medical-home. Accessed June 22 2012.

- 31.Bohmer RMJ. The four habits of high-value health care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(22):2045–2047. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1111087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green ML, Aagaard EM, Caverzagie KJ, et al. Charting the road to competence: developmental milestones for internal medicine residency training. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(1):5–20. doi: 10.4300/01.01.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aiyer M, Kukreja S, Ibrahim-Ali W, Aldag J. Discharge planning curricula in internal medicine residency programs: a national survey. South Med J. 2009;102(8):795–799. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181ad5ae8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alper E, Rosenberg EI, O’Brien KE, Fischer M, Durning SJ. Patient safety education at U.S. and Canadian medical schools: results from the 2006 Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine survey. Acad Med. 2009;84(12):1672–1676. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bf98a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glasheen JJ, Siegal EM, Epstein K, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists’ needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1110–1115. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0646-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eskildsen M, Bonsall J, Miller A, Ohuabunwa U, Payne C, Rimler E. Handover and Care Transitions Training for Internal Medicine Residents. MedEdPORTAL. 2012. Available at: www.mededportal.org/publication/9101. Accessed June 22 2012.