Abstract

Background

Communicating with patients about goals of care is an important skill for internal medicine residents. However, many trainees are not competent to perform a code status discussion (CSD). A multimodality intervention improved skills in a group of first-year residents in 2011. How long these acquired CSD skills are retained is unknown.

Objective

To study CSD skill retention one year after a multimodality intervention.

Design

This was a longitudinal cohort study.

Setting/Subjects

Thirty-eight second-year internal medicine residents in a university-affiliated internal medicine residency program participated in the study. Nineteen completed the intervention and 19 served as controls.

Measurements

Mean CSD clinical skills examination (CSE) scores using an 18-item checklist were compared after the intervention (2011) and one year later (2012).

Results

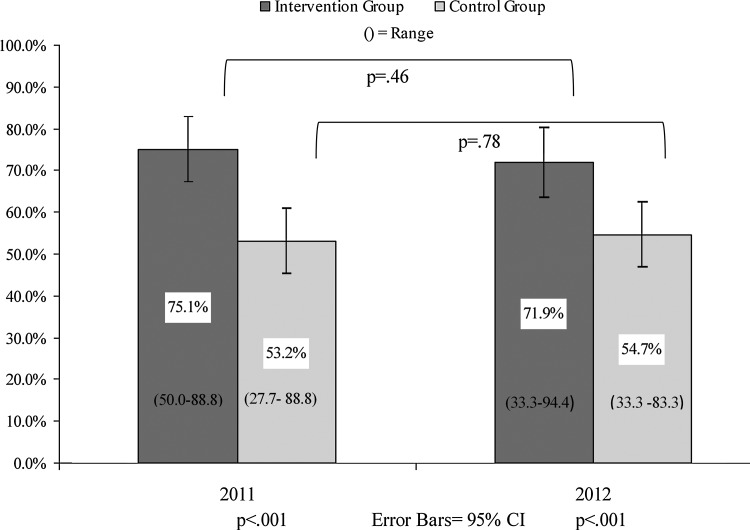

Intervention group residents performed significantly better than residents in the control group (71.9% (standard deviation [SD]=16.0%) versus 54.7% (SD=17.1%; p<0.001) at one-year follow-up. Intervention group residents retained their CSD skills at one year as performance was 75.1% in 2011 and 71.9% in 2012 (p=0.46). Control group residents did not develop additional CSD skills as 2011 checklist performance was 53.2% and 2012 performance was 54.7% (p=0.78).

Conclusions

CSD skills taught in a rigorous curriculum are retained at one-year follow-up. Residents in the control group did not acquire new CSD skills despite an additional year of training and clinical experience. Further study is needed to link improved CSD skills to better patient care quality.

Introduction

Physicians in training vary in their ability to communicate effectively with patients and families.1,2 This is despite the fact that competence in communication skills is required for residents and fellows in all disciplines.3 Although baseline competence is not assured, studies show that educational interventions improve skills in areas such as communicating with patients with cancer4 and patient-centered interviewing.5

Communicating with patients at the end of life is especially challenging for trainees. Physicians avoid breaking bad news,6 and concerns have been raised about the ability of residents and faculty to address end-of-life decision making with patients.7 Facilitating a code status discussion (CSD), in which patients facing serious illness have the opportunity to discuss goals and preferences for medical care and treatments, is a challenging and complex task. Yet, it is performed frequently by junior trainees in inpatient settings.8

Earlier research demonstrates that focused interventions improve trainee skill in facilitating end-of-life conversations.2,9,10 At Northwestern University, internal medicine residents completed a multimodality intervention in CSD skills including small group sessions, deliberate practice, and self-study.9 Skill was significantly better in intervention group residents than controls, as assessed by performance on a simulated CSD with a standardized patient. However, post-intervention skills were assessed only at 2 months,9 similar to short-term follow-up reported in other studies.2,10 The aim of the current study was to evaluate CSD skill retention one year after a communication skills intervention.

Method

This was a longitudinal cohort study of CSD skill retention. The study was performed at Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine in January 2012. The Northwestern University Institutional Review Board approved the study and all participants provided informed consent.

From July 2010 to January 2011, first-year internal medicine residents (n=38) were randomized to complete an intervention in CSD skills or serve as controls.9 All residents were graduates of United States medical schools; complete demographic information is available elsewhere.9 Nineteen residents completed the intervention including small group teaching, on-line modules, and a log of CSDs performed in actual clinical care.9 Nineteen residents completed clinical training alone and did not participate in the intervention. All 38 residents (intervention and control group) completed a CSD clinical skills examination (CSE) with a trained standardized patient in January, 2011. CSD skills were assessed via an 18-item behavioral checklist composed of three sections (a) patient-centered interviewing skills, (b) CSD skills, and (c) responding to emotion.9 Each checklist item was scored dichotomously (done correctly or done incorrectly) and given equal weight. Each item performed correctly received one point and points were summed for a total score. Intervention group residents performed significantly better than control group residents on the CSE.9 Residents in both groups received 10 to 15 minutes of individualized feedback from one of two trained hospice and palliative care certified faculty members after the CSE.

One year later, residents from both groups (n=38) were invited to participate in the current study to assess CSD skill retention. Residents were asked to perform a CSD with a trained standardized patient recruited from the Northwestern University Clinical Education Center using a standardized clinical scenario. CSD CSE scores from 2012 were compared with CSD CSE scores from 2011.

CSEs in 2011 and 2012 used the same format. In 2011, residents used a scenario of a patient admitted to the hospital with advanced colon cancer. In 2012, residents used a scenario of a patient with recurrent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma admitted to the hospital with fever and neutropenia. Residents were instructed to carry out the CSD as they would with an actual patient. Residents were allowed 15 minutes to complete the simulated CSD. CSDs were videotaped and one of two faculty members watched the interaction through closed-circuit video. This faculty member scored the CSE using the 18-item checklist and provided 10 to 15 minutes of individualized feedback to each resident.

A random sample of 19 of 38 (50%) of 2012 CSEs were rescored by a second rater to obtain inter-rater reliability. One rater was involved in the training intervention in 2011, but the second rater was blind to group assignment (intervention versus control) and results of the first rater's checklist score.

Participants reported self-confidence in leading an actual CSD using a 100-point scale (0=not confident and 100=very confident) and clinical experience with the procedure in actual clinical care. Whether or not participants rotated on the palliative care service 2-week elective during the study period was also collected.

The primary outcome measure was a comparison of group (intervention versus control) mean checklist scores in 2011 and 2012. Secondary outcome measures were CSD self-confidence and experience. Correlations were calculated between secondary outcomes and skill retention.

Checklist inter-rater reliability was estimated using the kappa coefficient.11 Mean CSE scores, clinical experience, and self-confidence for each occasion were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Differences between groups were assessed using Mann-Whitney U tests. Relationships between self-confidence, CSD clinical experience, and CSE performance in 2012 were assessed using Spearman correlations.

Results

All 38 residents consented to participate in the study and completed the entire protocol. Inter-rater reliability was substantial (kappa=0.69) across the 18 checklist items.

As shown in Figure 1, there was a statistically significant difference between group mean CSE scores. Intervention group residents retained their CSD skills as mean performance was 75.1% (SD=8.9%) in 2011 and 71.9% (SD=16.0%) in 2012 (p=0.46). Control group residents did not develop additional CSD skills as 2011 checklist mean performance was 53.2% (SD=16.2%) and 2012 performance was 54.7% (SD=17.1%; p=0.78). In both years, the difference between the intervention group and the control group was statistically significant (p<0.001).

FIG. 1.

Performance of internal medicine residents on a code status discussion clinical skills examination in 2011 and at one-year follow up.

Trainees in both groups reported performing approximately 25 CSDs in actual clinical care and reported high self-confidence. There was no significant correlation between 2012 follow-up CSE and self-confidence or CSD clinical experience (Table 1). Six residents rotated on palliative care during the study period. This did not significantly predict follow-up scores.

Table 1.

Code Status Discussion Clinical Experience, Self-Confidence, and Correlation with Clinical Skills Examination Performance in 2011 and 2012

| |

2011 Assessmenta |

2012 Follow-up |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention N=19 | Control N=19 | P value | Correlation with clinical skills examination performance | Intervention N=19 | Control N=19 | P value | Correlation with clinical skills examination performance | |

| Code status Discussion, no. performed | 6.2±3.7 | 11.7±13.2 | 0.49 | 0.13 | 24.5±18.9 | 24.8±29.1 | 0.57 | −0.13 |

| Code status Discussion, self-confidence | 65.0±14.6 | 60.5±13.4 | 0.49 | 0.18 | 79.7±12.1 | 71.8±14.3 | 0.09 | −0.07 |

Szmuilowicz E, et al., 2012.

Plus minus values are means±standard deviations.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that CSD skills acquired after a multimodality intervention were retained at one year. New postgraduate education models require that residents demonstrate competence in communicating with patients.12 In these models, academic advancement depends on achievement of predetermined competency milestones. However, use of competency-based education is complex because clinical skill retention in residents is rarely measured. Earlier research shows that skills are retained after simulation-based education in advanced cardiac life support and central venous catheter insertion.13,14 However, to our knowledge this is the first study to address retention of CSD skills, which are complex communication skills.

We believe that the primary reason why internal medicine residents retained CSD skills was that the original intervention was powerful and sustained.15 It lasted several months and required self-study and reflection in addition to participation in small group sessions lead by expert faculty.9 Clinical skill retention occurs when trainees participate actively and have time for deliberate practice and feedback.16 Similar results cannot be expected after passive interventions such as lectures.17 This is confirmed because control group residents did not improve after performing a CSD and receiving 10 to 15 minutes of feedback at the initial session in 2011. Educators should consider these findings when designing interventions to boost communication skills in trainees.

Another important finding is that residents in the control group did not acquire CSD skills despite an additional year of training and clinical experience. First-year residents in the intervention group performed significantly better in 2011 than second-year residents in the control group in 2012. Substantial evidence shows that cumulative experience is not a proxy for clinical skill.18 This may be because deliberate practice rarely occurs in clinical settings or because mistakes are passed down from faculty to learners.19 Effective health care communication has been linked to improved patient care.20,21 Our findings suggest that these skills will not develop in the absence of high-quality educational programs and rigorous assessment measures.

Lack of correlation between actual skill in leading a CSD and self-assessment of competency in experienced medical residents is another important finding. This result is similar to studies of emergency medicine, general surgery, and internal medicine residents.22–24 It emphasizes the need for clinical assessments that yield reliable data rather than reliance on self-assessment for competency determinations.

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted at one institution with a small sample size. Second, one rater performing checklist scoring was not blind to group assignment. This was addressed by including a second rater blinded to group status. Third, only one scenario was assessed during each CSE. Finally, we did not evaluate clinical outcomes. Further study is needed to link CSD education to improved physician-patient communication and quality of care. Replicating these findings through assessment of actual rather than simulated CSDs is an important next step.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that a CSD multimodality intervention yields skill improvement that is resistant to decay over one year. Leading a CSD requires complex skills that residents often fail to acquire in clinical training but that can be taught in a systematic way. We are encouraged that CSD skills, once attained, are maintained for one year. Based on these results, we require all residents complete training prior to performing a CSD in actual clinical care.

Acknowledgments

Dr. McGaghie's contribution was supported in part by the Jacob R. Suker, M.D., professorship in medical education and by grant UL RR 025741 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health (NIH). The NIH had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Lypson ML. Frohna JG. Gruppen LD. Woolliscroft JO. Assessing residents' competencies at baseline: Identifying the gaps. Acad Med. 2004;79:564–570. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szmuilowicz E. el-Jawahri A. Chiappetta L. Kamdar M. Block S. Improving residents' end-of-life communication skills with a short retreat: A randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:439–452. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: Common Program Requirements. www.acgme.org/acWebsite/dutyHours/dh_dutyhoursCommonPR07012007.pdf. [Apr 18;2012 ]. www.acgme.org/acWebsite/dutyHours/dh_dutyhoursCommonPR07012007.pdf

- 4.Chandawarkar RY. Ruscher KA. Krajewski A, et al. Pretraining and posttraining assessment of residents' performance in the fourth accreditation council for graduate medical education competency: patient communication skills. Arch Surg. 2011;146:916–921. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rimondini M. Del Piccolo L. Goss C, et al. The evaluation of training in patient-centered interviewing skills for psychiatric residents. Psychol Med. 2010;40:467–476. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosen S. Tesser A. Reluctance to communicate undesirable information: Mum effect. Sociometry. 1970;33:253–263. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orgel E. McCarter R. Jacobs S. A failing medical education model: A self-assessment by physicians at all levels of training of ability and comfort to deliver bad news. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:677–683. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billings ME. Curtis JR. Engleberg RA. Medicine residents' self-perceived competence in end-of-life care. Acad Med. 2009;84:1533–1539. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bbb490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szmuilowicz E. Neely KJ. Sharma RK, et al. Improving residents code status discussion skills: A randomized trial. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:768–774. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander SC. Keitz SA. Sloane R. Tulsky JA. A controlled trial of a short course to improve residents' communication with patients at the end of life. Acad Med. 2006;81:1008–1012. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000242580.83851.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleiss JL. Levin BA. Paik MC. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 3rd. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinberger SE. Pereira AG. Iobst WF. Mechaber AJ. Bronze MS. Internal medicine residency redesign. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:442–443. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-6-201103150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wayne DB. Siddall VJ. Butter J, et al. A longitudinal study of internal medicine residents' retention of advanced cardiac life support skills. Acad Med. 2006;81(10 Suppl):S9–S12. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200610001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barsuk JH. Cohen ER. McGaghie WC. Wayne DB. Long term retention of central venous insertion skills after simulation-based mastery learning. Acad Med. 2010;85(10 Suppl):S9–S12. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed436c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cordray DS. Pion GM. McKnight PE. Treatment strength and integrity: Models and methods. In: Bootzin RR, editor; Strengthening Research Methodology: Psychological Measurement and Evaluation. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Acad Med. 2004;79(10 Suppl):S70–S81. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200410001-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steele DJ. Medder JD. Turner P. A comparison of learning outcomes and attitudes in student- versus faculty-led problem-based learning: An experimental study. Med Educ. 2000;34:23–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choudhry NK. Fletcher RH. Soumerai SB. Systematic review: The relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:260–273. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-4-200502150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson WG. Chase R. Pantilat SZ. Tulsky JA. Auerbach AD. Code status discussions between attending hospitalist physicians and medical patients at hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;26:359–366. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1568-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Leary KJ. Buck R. Fligiel HM, et al. Structured interdisciplinary rounds in a medical teaching unit: Improving patient safety. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:678–684. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riley W. Davis S. Miller K. Hansen H. Sainfort F. Sweet R. Didactic and simulation nontechnical skills team training to improve perinatal patient outcomes in a community hospital. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37:357–364. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadosty AT. Bellolio MF. Laack TA, et al. Simulation-based emergency medicine resident self-assessment. J Emerg Med. 201;41:679–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipsett PA. Harris I. Downing S. Resident self-other assessor agreement: Influence of assessor, competency, and performance level. Arch Surg. 2011;146:901–906. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wayne DB. Butter J. Siddall VJ. Graduating internal medicine residents' self-assessment and performance of advanced cardiac life support skills. Med Teach. 2006;28:365–369. doi: 10.1080/01421590600627821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]