Abstract

Background and Objective

There is little evidence to support whether interventions that engage patients with symptomatic heart failure (HF) in preparedness planning impacts completion of advance directives (ADs). This study was conducted to assess the impact of a palliative care intervention on health perceptions, attitudes, receipt of information and knowledge of ADs, discussion of ADs with family and physicians, and completion of ADs in a cohort of patients with symptomatic HF.

Methods

Thirty-six patients hospitalized for HF decompensation were recruited and referred for an outpatient consultation with a palliative care specialist in conjunction with their routine HF follow-up visit after discharge; telephone interviews to assess health status and attitudes toward ADs were conducted before and 3 months after the initial consultation using an adapted version of the Advance Directive Attitude Survey (ADAS). Information pertaining to medical history and ADs was verified through medical chart abstraction.

Results and Conclusion

The current study found support for enhancing attitudes and completion of ADs following a palliative care consultation in patients with symptomatic HF. Despite a significant increase in attitudes toward completion of ADs following the intervention, only 47% of the participants completed ADs. This finding suggests that although education and understanding of ADs is important and can result in more positive attitudes, it does not translate to completion of ADs in all patients.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is an increasingly prevalent, often progressive condition characterized by marked physical disability, significant symptom burden, and poor quality of life.1–3 The need for early and regular discussions about patient preferences to enhance high-quality, patient-centered care have recently emerged in the HF literature with major emphasis placed on the need to facilitate preparedness planning and completion of advance directives (ADs). However, there is little evidence to support whether interventions that engage patients with symptomatic HF in preparedness planning impacts completion of ADs. This study was conducted to assess the impact of a palliative care intervention on health perceptions, attitudes, receipt of information and knowledge of ADs, discussion of ADs with family and physicians, and completion of ADs in a cohort of patients with symptomatic HF.

Methods

Study design, setting, and participants

This descriptive study was approved by the appropriate institutional review board; all study participants provided written, informed consent. Heart failure providers approached patients who were ≥18 years old during an episode of HF exacerbation requiring hospitalization about their interest in participating in the study. Subjects were excluded if they had diminished cognitive function, had a terminal co-morbid condition(s) with a life expectancy <6 months, were receiving care from a palliative care team, or had a left ventricular assist device.

Procedures

Thirty-six patients hospitalized for HF decompensation were recruited and referred for an outpatient consultation with a palliative care specialist (i.e., physician or advanced practice nurse) in conjunction with their routine HF follow-up visit 7 to 10 days after discharge; telephone interviews to assess health status and attitudes toward ADs were conducted before and 3 months after the initial palliative care consultation using an adapted version of the Advance Directive Attitude Survey (ADAS), a 24-item tool rated on a 4-point Likert scale.4 Information pertaining to medical history and ADs was verified through medical chart abstraction.

Measures

An adapted version of the ADAS was used to measure attitudes regarding ADs.8 The original 17-items covered (a) opportunity for treatment choices; (b) impact of ADs on the family; (c) effects of ADs on treatment; and (d) illness perceptions. Eight additional items focused on participants' perceptions of whether ADs influenced the amount and quality of end-of-life care, the ability to change decisions regarding end-of-life care once ADs were initiated, and their choice to make end-of-life care decisions. The possible range of scores on the adapted ADAS is 24 to 96; higher scores suggest more positive attitudes.

Data analyses

Bivariate comparisons between participants who completed ADs and those who did not were evaluated at baseline and 3 months using t tests or McNemar test and χ2 or Fisher's exact test depending on level of measurement. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 for all analyses (SPPS version 18; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Study participants were on average 53.9±8.0 years of age, predominantly male (72%), Caucasian (61%), married (69%), and New York Heart Association class II (69%) or III (31%) with a mean left ventricular ejection fraction of 25.4±5.2%.

Table 1 illustrates ADAS scores of completers and noncompleters pre- (28% versus 72%) and 3 months post-implementation (47% versus 53%) of a palliative care intervention based on gender, race, marital status, education, perceived health, receipt of information and knowledge of ADs, and discussion of ADs with family and physicians. At baseline, male participants had higher ADAS scores than female participants (p=0.028); no gender differences were noted in completion of ADs. Participants who were married, Caucasian, and college graduates, and those who perceived their health as good, received information regarding ADs, and described ADs in their own words, had more positive attitudes, and were more likely to complete ADs than their counterparts (all p<0.05).

Table 1.

Comparison of Scores on the Advance Directive Attitude Scale Based on Sociodemographic and Health Status among Completers and Noncompleters of Advance Directives at Baseline and 3 Months (n=36)

| |

|

Baseline |

Follow-up (3 months) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Group | N | Completers (n=10) | N | Noncompleters (n=26) | P value | N | Completers (n=17) | N | Noncompleters (n=19) | P value |

| Gender | Male | 9 | 74.11±4.37 | 17 | 53.29±9.48 | 0.028 | 14 | 79.86±7.34 | 12 | 56.58±7.72 | 0.106 |

| Female | 1 | 69.00±------ | 9 | 47.89±8.51 | 3 | 78.33±9.07 | 7 | 52.86±6.12 | |||

| Race | Caucasian | 10 | 73.60±4.43 | 12 | 52.83±7.02 | 0.020 | 16 | 79.44±7.58 | 6 | 57.67±4.08 | 0.000 |

| Black | 0 | ---- | 9 | 49.78±11.68 | 1 | 82.00±---- | 8 | 56.75±7.31 | |||

| Hispanic | 0 | ---- | 5 | 51.00±11.25 | 0 | ---- | 5 | 49.80±8.41 | |||

| Marital status | Married | 10 | 73.60±4.43 | 16 | 54.69±9.09 | 0.001 | 14 | 81.36±6.64 | 12 | 55.75±7.25 | 0.048 |

| Not married | 0 | ---- | 10 | 46.20±7.49 | 3 | 71.33±4.93 | 7 | 54.29±7.65 | |||

| Education | ≤High school | 0 | ---- | 10 | 45.70±6.15 | 0.001 | 2 | 68.50±0.71 | 8 | 53.25±7.87 | 0.008 |

| High school grad | 5 | 70.80±2.49 | 8 | 52.00±8.72 | 7 | 79.00±8.62 | 6 | 53.83±7.44 | |||

| College | 5 | 76.40±4.27 | 8 | 58.00±9.56 | 8 | 82.88±3.56 | 5 | 60.00±4.30 | |||

| Perceived health | Very Good | 9 | 56.17±7.75 | 3 | 29.13±9.08 | 0.000 | 10 | 73.78±4.66 | 4 | 49.54±7.21 | 0.020 |

| Good | 1 | 83.00±------ | 10 | 54.33±6.91 | 7 | 72.00±6.41 | 11 | 54.70±11.55 | |||

| Poor-Fair | 0 | ---- | 13 | 55.21±7.23 | 0 | ---- | 4 | 48.67±9.71 | |||

| Informed about ADs | Yes | 10 | 64.24±12.63 | 13 | 51.63±12.63 | 0.010 | 17 | 79.44±7.58 | 19 | 57.67±4.08 | 0.000 |

| No | 0 | ---- | 13 | 55.21±7.23 | 0 | ---- | 0 | ---- | |||

| Knowledge | Yes | 10 | 73.60±4.43 | 7 | 54.69±9.09 | 0.001 | 14 | 81.36±6.64 | 7 | 54.29±7.65 | 0.048 |

| No | 0 | ------– | 19 | 46.20±7.49 | 3 | 71.33±4.93 | 12 | 55.75±7.25 | |||

| Discussed ADs with family | Yes | 4 | 73.00±5.66 | 6 | 51.00±7.01 | 0.534 | 17 | 83.80±5.00 | 4 | 68.64±8.92 | 0.000 |

| No | 6 | 74.00±3.95 | 20 | 51.55±10.17 | 0 | ---- | 15 | 53.93±7.13 | |||

| Discussed ADs with physician | Yes | 4 | 73.00±5.66 | 6 | 53.25±7.34 | 0.471 | 9 | 81.11±6.17 | 14 | 58.40±9.29 | 0.000 |

| No | 6 | 74.00±3.95 | 20 | 50.61±10.22 | 8 | 77.88±8.63 | 8 | 54.07±6.37 | |||

Possible range of scores on the Advance Directive Attitude Scale is 24 to 96; higher scores suggest more positive attitudes.

AD, advance directive.

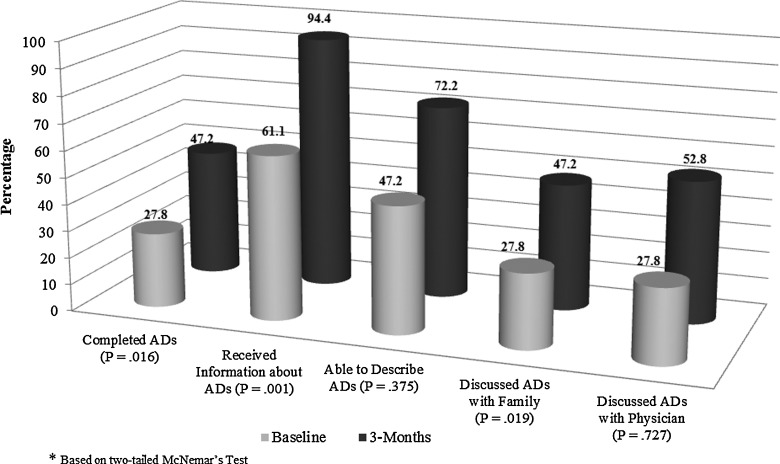

Average scores on the ADAS increased from 57% to 80% (p<0.001) from baseline to 3 months (Fig. 1); likewise, the number of participants who completed ADs increased (28% versus 47%, p=0.016). All participants who completed ADs at the two time points scored ≥65 on the ADAS. At 3 months, participants who were married and college graduates continued to have higher scores on the ADAS compared with their counterparts (all p<0.05); however, there were no significant differences between completers and noncompleters based on these sociodemographic variables. The only sociodemographic characteristic that was associated with positive attitudes and completion of ADs post-intervention was race; Caucasians had higher ADAS scores and were more likely to complete ADs than African Americans and Hispanics (ƛ2=14.93, p=0.001). Although participants' health perceptions and knowledge of ADs at 3 months did not distinguish completers and noncompleters, the ADAS scores were still significantly higher for participants who perceived their health as good to very good versus poor to fair (p=0.020) and participants who were able to define or describe what ADs were in their own words versus those who were not (p=0.048). Participants who discussed ADs with family members were more likely to complete ADs during the 3-month follow-up (ƛ2=6.11, p=0.013).

FIG. 1.

Proportions of participants who completed advance directives (ADs), received information about ADs, were able to describe ADs, and discussed ADs with family and physicians at baseline and at 3 months (n=36).

Discussion

To our knowledge this study is the first to examine the impact of a palliative care intervention on attitudes and completion of ADs in a single cohort of patients recently hospitalized with HF exacerbation. Our findings show that a palliative care consultation improved completion of ADs from 28% to 47% (p=0.016). These rates are considerably higher than previously reported rates of 15% to 25% in patients with cancer,5 but lower than reported rates of 41% in community HF patients.6 We speculate these differences are related to the fact that our sample was composed of a fairly homogeneous group of patients with symptomatic HF. Our results are consistent with a recently published advance care planning intervention for HF7; however, our participants met with a palliative care clinician rather than a certified facilitator and our participation rate was greater than 31.8%. Thus, our findings may be more applicable to the palliative care clinician's practice.

Attitudes toward and completion of ADs improved significantly after participants received palliative care consultation. These findings support the potential benefit of engaging patients with symptomatic HF and family in preparedness planning and providing them with opportunities to discuss their values, wishes, goals, and preferences related to their care during their initial visit with the palliative care physician or advanced practice nurse. The lack of a more favorable increase in completion of ADs post-intervention in our sample suggests that perhaps patients with HF are more likely to believe that there is a cure for their disease and also that they may have a lot of uncertainly in their minds in terms of the benefits of advance care planning and therefore are still more eager to seek definitive treatment for their condition. Although not all participants who reported improved attitudes or had high ADAS scores completed ADs, ADAS scores were higher for those who completed ADs than those who did not. This result is consistent with previous research that showed that the more positive people are toward ADs the higher the likelihood that they will complete them.4 Our findings indicate that preparedness planning initiated during a palliative care consultation may be a necessary first step to the ultimate completion of an AD, but more importantly, to respecting patients' wishes and preferences the next time they are admitted to the hospital.

Our findings related to race are consistent with previous studies examining racial disparities in completion of ADs in older adults8,9 and nursing home residents10; the literature suggests that among Caucasians, higher completion rates reflect their strong individualistic values of dominance when it comes to decision making, as opposed to the family-centered approach of non-Caucasians.11 Future research examining relationships between sociodemographic variables and attitudes toward ADs in a larger sample is warranted to better explicate the impact of personal characteristics on completion of ADs.

Likewise, we found that participants who reported having discussions about ADs with their family members were more likely to complete ADs after the palliative care consultation. This is consistent with earlier reports that communication among patients and families about treatment choices, the possibility of death, and comfort at the end of life facilitates decisions to complete ADs.12 Interestingly, we found that although having discussions related to end-of-life care with health care providers did enhance attitudes toward ADs, completion rates for ADs did not necessarily improve. Previous research acknowledges that primary care physicians and cardiologists may not be adequately trained to address these discussions and further support the importance of referring patients with symptomatic HF to a palliative care specialist.13,14

This study has several limitations. The sample size was small and did not meet the requirements of a priori power analysis. All participants were recruited from a single tertiary care facility and were considerably younger than the general population of HF patients, which may not be representative of patients with symptomatic HF. Finally, our findings are limited by the lack of a comparison group. Future research that uses stratified random or quota sampling across multiple sites may potentially enhance generalization of findings related to the impact of palliative care on attitudes and completion of ADs.

Conclusion

The current study found support for enhancing attitudes and completion of ADs following a palliative care consultation in patients with symptomatic HF. Despite a significant increase in attitudes toward completion of ADs following receipt of a palliative care intervention, only 47% of the participants completed ADs. This finding suggests that although education and understanding of ADs is important and can result in more positive attitudes, it does not translate to completion of ADs in all patients. The benefits of a palliative care consultation on attitudes and completion of ADs should be examined in a larger scale, prospective, randomized clinical trial sufficiently powered to assess clinical outcomes. Likewise, research that examines other known predictors of completion of ADs (e.g., interventions that enhance perceived health or encourage discussions about ADs among patients, family, and specialized health care providers) are warranted to better explicate their role in increasing completion of ADs in patients with symptomatic HF.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1R01HL093466-01) and the University of California, Los Angeles, Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research/Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly (RCMAR/CHIME) under the National Institute in Aging (P30-AG02-1684, PI, C. Mangione). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–National Institutes of Health or the National Institute on Aging.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Walden J. Stevenson LW. Dracup K. Extended comparison of quality of life between stable heart failure patients and heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transp. 1994;13:1109–11018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grady K. Jalowiec A. White-Williams C. Pifarre R. Kirklin J. Bourge R, et al. Predictors of quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1995;14:2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry C. McMurray J. A review of quality of life evaluations in patients with congestive heart failure. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;16:247–271. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199916030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douglas R. Brown HN. Patients' attitudes toward advance directives. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34:61–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jezewski MA. Meeker MA. Schrader M. Voices of oncology nurses: What is needed to assist patients with advance directives. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26:105–112. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunlay SM. Swetz KM. Mueller PS. Roger VL. Advance directives in community patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:283–289. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.966036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schellinger S. Sidebottom A. Briggs L. Disease specific advance care planning for heart failure patients: Implementation in a large health system. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:1224–1230. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alano GJ. Pekmezaris R. Tai JY. Hussain MJ. Jeune J. Louis B, et al. Factors influencing older adults to complete advance directives. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8:267–275. doi: 10.1017/S1478951510000064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwak J. Haley WE. Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist. 2005;45:634–641. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rich SE. Gruber-Baldini AL. Quinn CC. Zimmerman SI. Discussion as a factor in racial disparity in advance directive completion at nursing home admission. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:146–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnato A. Anthony D. Skinner J. Gallagher P. Fisher E. Racial and ethnic differences in preferences for end-of-life treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;24:695–701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0952-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norton S. Talerico S. Facilitating end-of-life decision-making: Strategies for communicating and assessing. J Geront Nurs. 2000;26:6–13. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20000901-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Leary N. Murphy NF. O'Loughlin C. Tiernan E. McDonald K. A comparative study of the palliative care needs of heart failure and cancer patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:406–412. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Low J. Pattenden J. Candy B. Beattie JM. Jones L. Palliative care in advanced heart failure: An international review of the perspectives of recipients and health professionals on care provision. J Card Fail. 2011;17:231–252. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]