Summary

Guanylyl cyclases mediate a number of physiological processes, including smooth muscle function and axonal guidance. Here, we report a novel role for Drosophila receptor-type guanylyl cyclase at 76C, Gyc76C, in development of the embryonic somatic muscle. In embryos lacking function of Gyc76C or the downstream cGMP-dependent protein kinase (cGK), DG1, patterning of the somatic body wall muscles was abnormal with ventral and lateral muscle groups showing the most severe defects. In contrast, specification and elongation of the dorsal oblique and dorsal acute muscles of gyc76C mutant embryos was normal, and instead, these muscles showed defects in proper formation of the myotendinous junctions (MTJs). During MTJ formation in gyc76C and pkg21D mutant embryos, the βPS integrin subunit failed to localize to the MTJs and instead was found in discrete puncta within the myotubes. Tissue-specific rescue experiments showed that gyc76C function is required in the muscle for proper patterning and βPS integrin localization at the MTJ. These studies provide the first evidence for a requirement for Gyc76C and DG1 in Drosophila somatic muscle development, and suggest a role in transport and/or retention of integrin receptor subunits at the developing MTJs.

Keywords: Guanylyl cyclase, Drosophila, Muscle, Integrin, Adhesion

Introduction

Guanylyl cyclases (GCs) are a family of soluble and receptor-type enzymes that catalyze the conversion of GTP to cGMP (guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate) in both vertebrates and invertebrates. GCs synthesize cGMP in response to signals, such as nitric oxide (NO), peptide ligands and changes in intracellular calcium (Davies, 2006; Lucas et al., 2000; Morton, 2004; Overend et al., 2012). Intracellular cGMP regulates cellular events through cGMP-dependent protein kinases (cGKs), ion channels or phosphodiesterases, with cGKs representing the major intracellular effectors of cGMP signaling (Davies, 2006; Lucas et al., 2000). The Drosophila genome encodes at least seven receptor and receptor-like GCs (Morton and Hudson, 2002). Drosophila cGKs are encoded by two genes, pkg21D (dg1) and foraging (for, dg2). Some physiological functions of cGKs may be conserved between Drosophila and mammals. Both DG1 and DG2 modulate epithelial fluid transport by the Malpighian (renal) tubules (MacPherson et al., 2004) and mouse knock-outs of cGKII result in intestinal secretory defects (Pfeifer et al., 1996). Although GCs and cGMP signaling are known to regulate multiple cellular and physiological events (Davies and Day, 2006; Davies, 2006; Lucas et al., 2000), their role in embryogenesis is poorly understood. In Drosophila, Guanylyl cyclase (Gyc) 32E is involved in oogenesis and in egg chamber development whereas Gyc76C is involved in axon guidance (Ayoob et al., 2004; Gigliotti et al., 1993).

During embryogenesis adhesion of cells to one another and to the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM) gives rise to three-dimensional tissues and organs. While some types of adhesions are stable, such as those between muscle and tendon cells, others, such as those between a migrating cell and the substratum upon which it migrates are transient. Cell-substratum adhesion is mediated by the integrin family of transmembrane adhesion receptors. Integrins exist as a heterodimer composed of a single α and a single β subunit that assemble into large intracellular protein complexes to regulate ECM binding and signaling to the cytoskeleton (Hynes, 2002). In osteoclasts and pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells cGKI plays a role in integrin-mediated adhesion (Negash et al., 2009; Yaroslavskiy et al., 2005). Specifically, in osteoclasts, cGK1 reorganizes αvβ3 integrin-mediated adhesion during cGMP-induced cell motility (Yaroslavskiy et al., 2005). Although these studies link cGMP signaling to integrin-mediated adhesion, whether cGMP signaling affects integrin-dependent adhesion in a developmental context is not known.

The Drosophila genome encodes two β integrin subunits and five α integrin subunits (Bökel and Brown, 2002). During Drosophila embryogenesis, integrins are required for the migration of a number of cell types, such as cells of the primordial mid gut, salivary gland and trachea (Boube et al., 2001; Bradley et al., 2003; Martin-Bermudo et al., 1999; Roote and Zusman, 1995). Integrins are also required for the formation of stable adhesions, such as those at the MTJs, in humans (Hayashi et al., 1998) and in Drosophila (Brown et al., 2000). In Drosophila, growing myotubes elongate towards epidermal-derived tendon cells until they reach their respective tendon cells to form MTJs (Bate, 1990; Baylies et al., 1998; Brown et al., 2000; Schnorrer and Dickson, 2004; Schweitzer et al., 2010). In the absence of integrin function, the initial specification, fusion and attachment of muscle to tendon proceeds normally; however, muscles subsequently detach and round up (Brabant and Brower, 1993; Brown, 1994; Martin-Bermudo and Brown, 1996; Newman and Wright, 1981; Prokop et al., 1998). In this study, we report on a novel function for a receptor-type guanylyl cyclase, Gyc76C, and its downstream cGMP-dependent protein kinase, DG1, in Drosophila somatic muscle development, in particular, βPS integrin subunit localization at the developing MTJs.

Results

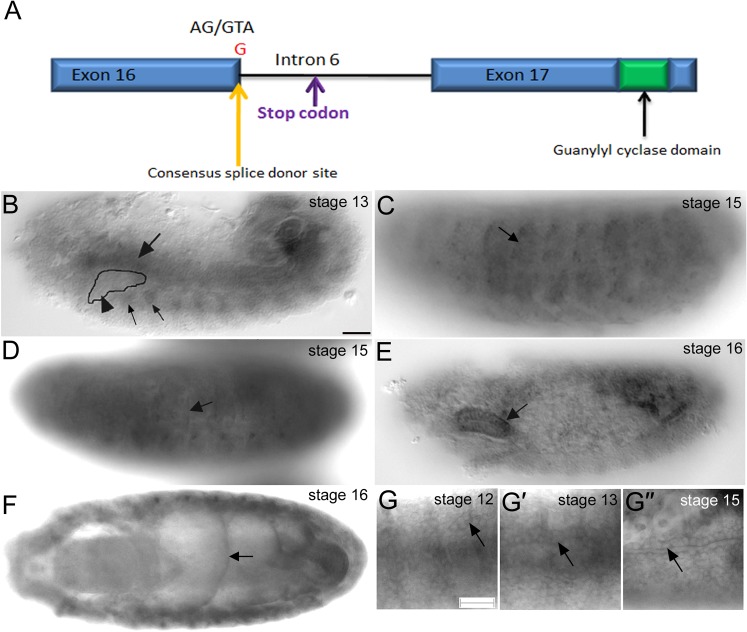

From a large-scale EMS mutagenesis screen, we identified several mutations affecting salivary gland and/or tracheal development (Myat et al., 2005). We previously reported that one of the mutations, gimli2388, affects tracheal branch migration (Myat et al., 2005). Through deficiency mapping, we identified the mutation in gimli2388 as a novel allele of the receptor-type guanylyl cyclase at 76C (Gyc76C), hereafter referred to as gyc76C2388 (see Materials and Methods on mapping of gyc76C2388). The gyc76C2388 mutation is a single nucleotide change of T to G in the 5′ end of the intron sequence following exon 16 changing the conserved GU at the splice donor site to GG. This nucleotide change results in the insertion of 92 intron base pair sequences from intron 6 which contains an in-frame stop codon before the guanylyl cyclase domain (Fig. 1A). Thus, the Gyc76C protein produced in gyc76C2388 mutant embryos likely lacks the cyclase domain.

Fig. 1. Molecular lesion of gyc76C2388 and gyc76C RNA expression in the Drosophila embryo.

A single nucleotide change from T to G in the 5′ intron sequence following exon 16 changes the conserved GU at the splice donor site to GG. This nucleotide change is followed by the insertion of 92 base pairs of intron 6 that contain an in-frame stop codon before the guanylyl cylcase domain (A). gyc76C RNA is expressed in the circular visceral mesoderm (CVM) (B, large arrow) overlying the migrating salivary gland (B, arrowhead) and in the fat body (FB) (B, small arrows) underlying the gland at stage 13, in the lateral body wall muscles (C, arrow) and in the tendon cells (D, arrow) at stage 15 and salivary gland (E, arrow) and midgut constrictions (F, arrow) at stage 16. gyc76C RNA is also expressed in the developing trachea (G) when primary branches such as the dorsal trunk (DT) are migrating out (G, arrow) at stage 12, when the DT undergoes anastomosis (G′) at stage 13 and is enriched apically in DT cells (G″) at stage 15. All embryos shown were processed for in situ hybridization to gyc76C RNA. Scale bar in B and G represents 20 µm.

To understand gyc76C function in Drosophila embryogenesis, we analyzed the embryonic expression of gyc76C RNA. Drosophila gyc76C was previously shown to be expressed in the germarium during oogenesis and egg chamber development (Gigliotti et al., 1993) and later in embryonic and adult tissues with a particular enrichment in the adult salivary glands (Chintapalli et al., 2007; Liu et al., 1995; McNeil et al., 1995). In mid-embryogenesis, gyc76C RNA was enriched in the circular visceral mesoderm (CVM) that overlies the migrating salivary gland and in the fat body (FB) that underlies the gland but at background levels in the gland itself (Fig. 1B). In late embryogenesis, gyc76C RNA was detected in the mature salivary gland, in the somatic body wall muscles and the tendon cells to which the muscles attach, and in the constricting midgut (Fig. 1C–F). gyc76C RNA was also expressed in the migrating tracheal cells at mid-embryogenesis and in the developed trachea at the end of embryogenesis with enrichment of the transcript in the apical domains (Fig. 1G). Thus, the RNA expression pattern of gyc76C is consistent with the tracheal (Myat et al., 2005) and salivary gland (U.P. and M.M.M., unpublished) defects observed in gyc76C2388 mutant embryos.

Gyc76C is required for somatic muscle development

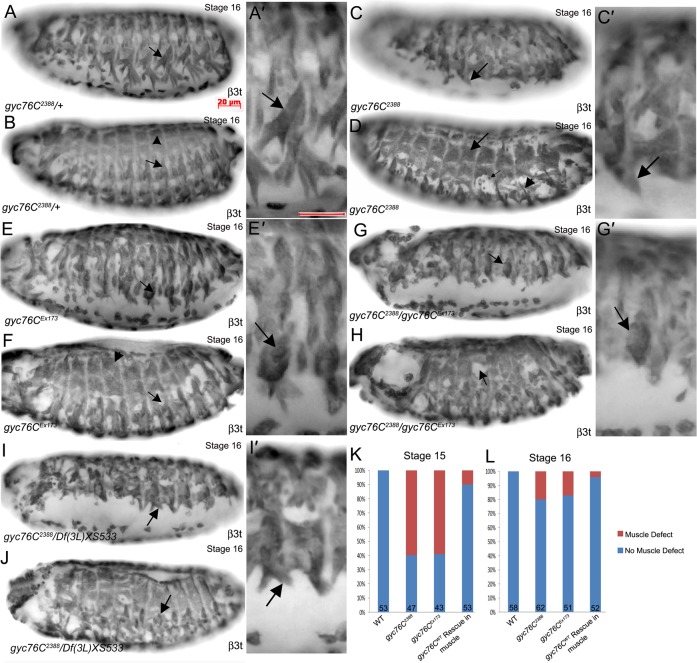

Due to the prominent RNA expression of gyc76C in the somatic muscles, we investigated the role of gyc76C in embryonic somatic muscle development. The Drosophila somatic muscle consists of 30 mature muscles in each abdominal hemisegment that develop during mid- to late embryogenesis (Beckett and Baylies, 2006; Frasch, 1999). gyc76C2388 homozygous embryos showed an abnormal muscle pattern with numerous ventral and lateral muscles that failed to extend or were missing compared to heterozygous siblings (Fig. 2A–D). Free unfused fusion competent myoblasts (FCMs) were present in some gyc76C2388 homozygous embryos, suggesting a defect in myoblast fusion (Fig. 2D). In contrast to the ventral and lateral muscles, dorsal muscles were largely unaffected by loss of gyc76C (Fig. 2B,D). Scoring gyc76C2388 heterozygous and homozygous embryos for gross patterning defects in the ventral and lateral muscles showed that although 60% of gyc76C2388 homozygous embryos showed muscle defects at stage 15, only 20% showed defects by stage 16 indicating delayed muscle development (Fig. 2K,L). We observed similar defects in embryos homozygous for gyc76CEx173, an allele in which about 8 kb of genomic DNA including a gyc76C exon are deleted by imprecise P-element excision (Ayoob et al., 2004) and embryos trans-heterozygous for gyc76C2388 and gyc76CEx173 (Fig. 2E–H). To test whether the gyc76C2388allele is a null allele, we analyzed embryos trans-heterozygous for gyc76C2388 and two overlapping deficiencies that delete the entire gyc76C gene, Df(3L)fln1 and Df(3L)XS533 (Table 1). We observed defects in somatic muscle patterning in embryos trans-heterozygous for gyc76C2388and either Df(3L)fln1 or Df(3L)XS533 to a similar severity as gyc76C2388 homozygous embryos suggesting that gyc76C2388 is either a null or a strong hypomorph allele (Fig. 2I,J; data not shown).

Fig. 2. Gyc76C mutant embryos have defects in muscle development.

In gyc76C2388 heterozygous embryos (A,B), ventral muscles (A,A′, arrows), lateral muscles (B, arrow) and dorsal muscles (B, arrowhead) are patterned normally. In gyc76C2388 homozygous embryos (C,D), ventral muscles (C,C′, arrows) and lateral muscles (D, arrowhead) are not patterned normally and unfused myoblasts are present (D, small arrow), whereas the dorsal muscles are patterned normally (D, arrow). In gyc76CEx173 homozygous embryos (E,F) and trans-heterozygous embryos of gyc76C2388 and gyc76CEx173 (G,H), patterning of the ventral muscles (E′,G′, arrows) and lateral muscles (F,H, arrows) is abnormal, whereas the dorsal muscles (F, arrowhead) are patterned normally. In embryos trans-heterozygous for gyc76C2388and Df (3L) XS533 (I,J), the ventral muscles (I,I′, arrows) and lateral muscles (J, arrow) are abnormally patterned. Graph depicting percentage of wild-type (WT), gyc76C2388 and gyc76CEx173 mutant embryos and muscle-specific rescue embryos with patterning defects in the somatic muscle at stages 15 and 16 (K,L). Numbers indicate number of embryos scored. All embryos shown are at stage 16 and were stained for β3 tubulin (β3t) which labels all somatic muscles. Scale bars in A,A′ represent 20 µm.

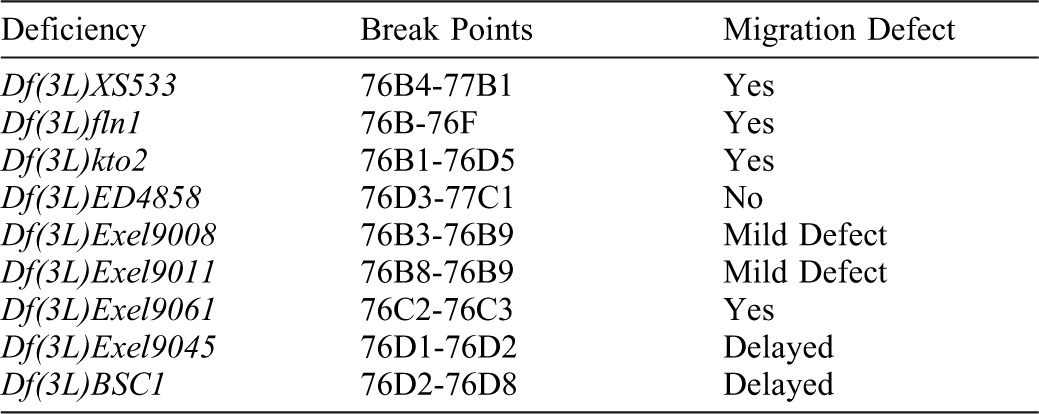

Table 1. Deficiency lines used for mapping the gimli2388 salivary gland migration defect.

To test whether gyc76C acts cell-autonomously to regulate somatic muscle development, we expressed wild-type gyc76C (gyc76CWT) in the somatic and visceral muscle with twi-GAL4; mef2-GAL4. Muscle-specific expression of gyc76CWT in gyc76C2388 homozygous embryos was sufficient to restore the normal pattern of the somatic body wall muscles such that only 10% of embryos showed muscle defects instead of 60% at stage 15 and only 5% of rescue embryos at stage 16 showed a patterning defect instead of 20% (Fig. 2K,L). These data suggest that gyc76C function is required in the somatic muscle for proper patterning.

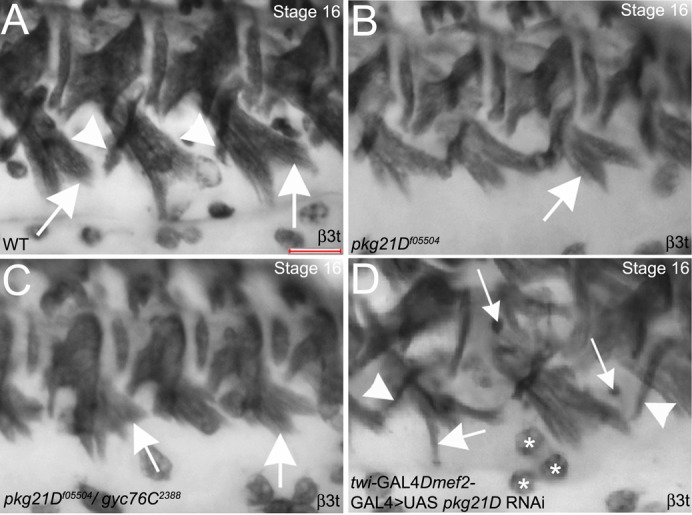

Loss of pkg21D phenocopies the gyc76C mutant muscle patterning phenotype

To determine whether the Drosophila cGMP-dependent kinases DG1 and DG2 were required for somatic muscle patterning, like gyc76C, we analyzed embryos mutant for pkg21D and foraging (for), encoding DG1 and DG2, respectively. We analyzed two viable hypomorph alleles of pkg21D, pkg21Df05504 and pkg21D24228. In embryos mutant for either pkg21D allele, somatic muscles were patterned normally with mild defects in extension of the ventral oblique (VO) muscles (Fig. 3B; data not shown). Similarly, in embryos trans-heterozygous for gyc76C2388 and pkg21Df05504, somatic muscle patterning was largely intact and extension of the VO muscles was mildly affected (Fig. 3C). To deplete the developing embryo of maternal and zygotic pkg21D, we expressed RNAi to pkg21D specifically in the muscle. We observed significantly more severe defects with DG1 knockdown in somatic muscle patterning with thinned VO and ventral acute (VA) muscles and the presence of FCMs, suggesting an earlier defect in myoblast fusion (Fig. 3D). We did not detect muscle defects in embryos mutant for for12326 or embryos expressing for RNAi specifically in the muscle (data not shown).

Fig. 3. DG1 regulates somatic muscle patterning and myotube extension with Gyc76C.

In stage 16 wild-type embryos (A), VO (A, arrows) and VA (A, arrowheads) muscles extend towards the ventral midline. In pkg21Df05504 mutant embryos (B) and embryos trans-heterozygous for pkg21Df05504 and gyc76C2388 (C), VO muscles are not as extended (B,C, arrows). In embryos expressing pkg21D RNAi specifically in the muscle with twi-GAL4; mef2-GAL4 (D), VO (D, large arrow) and VA (D, arrowheads) muscles are thinned and unfused myoblasts are present (D, small arrows). Embryos shown were stained for β3t which labels all somatic muscles as well as hemocytes (asterisks in D) in the vicinity. Scale bar in A represents 20 µm.

Gyc76C and DG1 control integrin localization at the myotendinous junctions of dorsal muscles

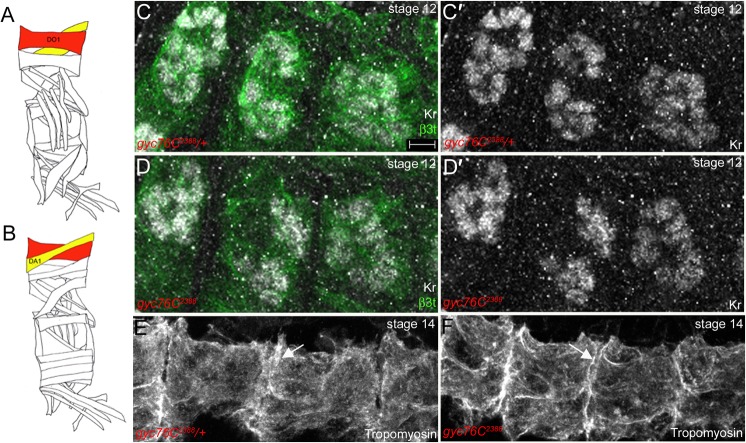

In contrast to the severe patterning defects observed for the ventral and lateral muscles in gyc76C2388 and pkg21D-RNAi-treated embryos, the dorsal muscles of gyc76C2388 and gyc76CEx173 homozygous embryos were largely intact with no unfused FCMS or gaps within the musculature (Fig. 2D,F). Thus, we focused our analysis on the dorsal oblique 1 (DO1) and dorsal acute 1 (DA1) muscles to test whether gyc76C and pkg21D are required for proper formation of the myotendinous junctions (MTJs) which mediate attachment of muscles to their respective epidermal-derived tendon cells in an integrin-dependent manner. We first confirmed that specification and elongation of the dorsal muscles was not affected by loss of gyc76C. Staining for Kruppel which specifies the identity of several body wall muscles, including the DO and DA muscles (Fig. 4A,B) (Ruiz-Gómez et al., 1997) revealed that gyc76C2388 homozygous embryos had a comparable number of DO1 and DA1 muscle nuclei to that of heterozygous siblings (Fig. 4C,D). Moreover, staining for tropomyosin, which localizes to the cortex of all muscle cells, demonstrated that the DO1/DA1 muscles elongated towards the segment borders in gyc76C2388 homozygous embryos as in heterozygous siblings (Fig. 4E,F).

Fig. 4. Dorsal muscle specification and elongation are normal in gyc76C mutant embryos.

(A,B) Schematic diagrams of somatic muscles highlighting the external dorsal oblique (DO) muscles (A,B, red) and the internal dorsal acute (DA) muscles (A,B, yellow). In gyc76C2388 heterozygous and homozygous embryos (C,D), DO and DA muscles labeled with Kruppel (Kr) (C′,D′, white) are specified normally. In gyc76C2388 heterozygous (E) and homozygous (F) embryos, DO and DA muscles elongate to span the entire length of the segment (E,F, arrows). Embryos in C,D were stained for Kr in white and β3t in green, whereas embryos in E,F were stained for Tropomyosin. All embryos were stained for β-galactosidase (β-gal) to distinguish heterozygous from homozygous embryos (not shown). Embryos in C,D are at stage 12 and those in E,F at stage 14. Diagrams in A,B were adapted from Beckett and Baylies, 2003. Scale bar in B represents 5 µm.

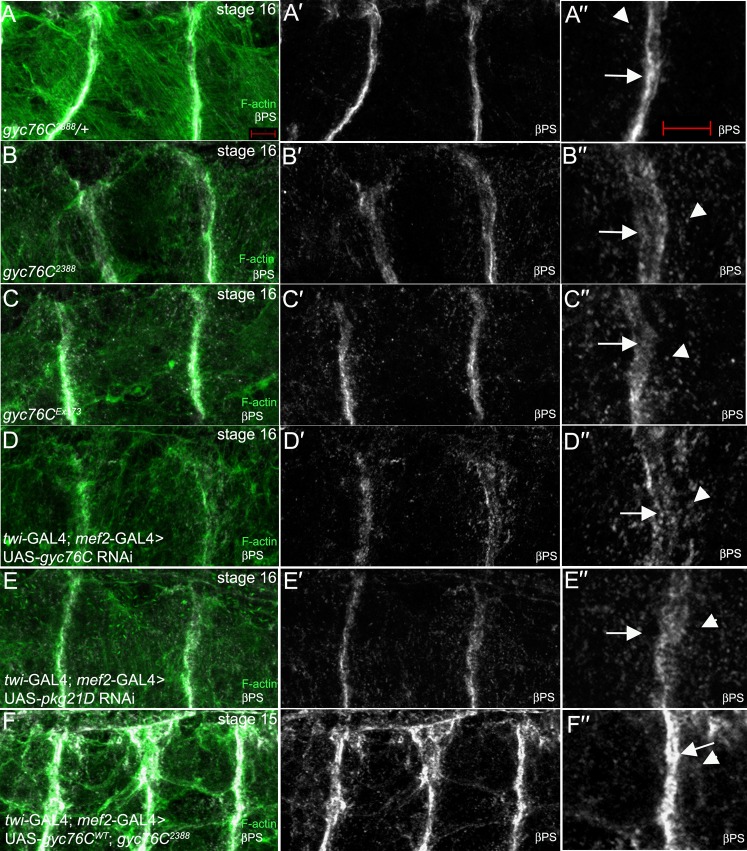

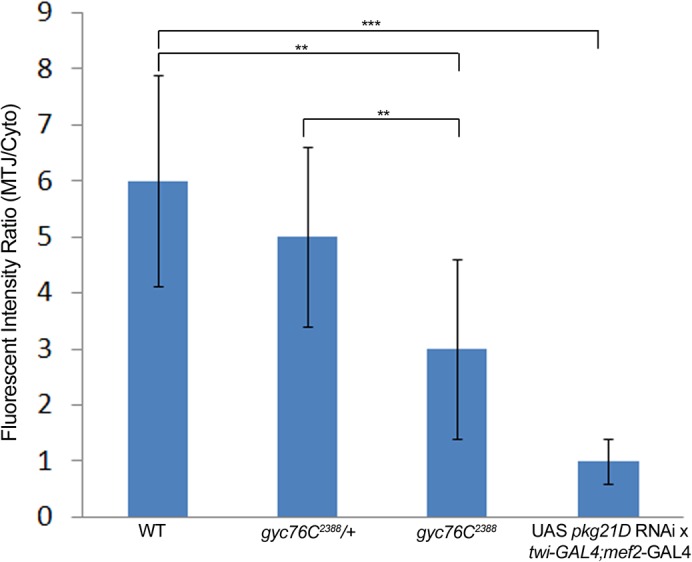

Attachment of the body wall muscles to tendon cells at MTJs occurs in an integrin-dependent manner (Schejter and Baylies, 2010; Schweitzer et al., 2010). In stage 16 gyc76C2388 heterozygous embryos, the βPS integrin subunit was highly enriched at the MTJ of DO1/DA1 muscles with very little βPS present in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5A). By contrast, in stage 16 gyc76C2388 homozygous embryos, βPS at the MTJ was significantly reduced and its presence in the cytoplasm as discrete puncta was increased (Fig. 5B). We quantified the change in βPS localization observed in gyc76C2388 mutant embryos by measuring the fluorescent intensity ratio at the MTJs and in the cytoplasm (see Materials and Methods). Our measurements showed that while wild-type and gyc76C2388 heterozygous embryos showed a fluorescent intensity ratio between 5 and 6, gyc76C2388 homozygous embryos showed a reduced ratio of approximately 3, suggesting reduced presence of βPS at the MTJ and/or increased presence in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6). We observed similar defects in integrin localization in embryos homozygous for gyc76CEx173 (Fig. 5C) and in embryos expressing RNAi to gyc76C specifically in the muscle (Fig. 5D). In embryos expressing RNAi to pkg21D, βPS at the MTJ was similarly reduced and its presence as puncta in the cytoplasm of the DO1/DA1 muscles was increased (Fig. 5E). Measurement of fluorescent intensity ratio demonstrated that inhibition of DG1 resulted in an almost equal distribution of βPS between the MTJ and cytoplasm (Fig. 6). To determine whether gyc76C function was required in the muscle for proper localization of βPS at the MTJ, we expressed gyc76CWT in the muscle of gyc76C2388homozygous embryos. Expression of gyc76CWT in the muscle of gyc76C2388homozygous embryos rescued the βPS localization defect such that βPS was now enriched at the MTJ and continued to localize to intracellular puncta within the myotubes (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5. gyc76C and pkg21D control integrin localization at the MTJ.

In gyc76C2388 heterozygous embryos (A), βPS integrin (A′,A″, white) and F-actin (A, green) accumulate at MTJs (A″, arrow) and in intracellular puncta (A″, arrowhead). In embryos homozygous for gyc76C2388 (B) or gyc76CEx173 (C), and embryos expressing RNAi to gyc76C (D) or pkg21D (E) specifically in the muscle with twi-GAL4; mef2-GAL4, βPS (B′–E′,B″–E″) is diffused at the MTJs (B″–E″, arrows) and is found as intracellular puncta in the dorsal muscles (B″–E″, arrowheads). In gyc76C2388 homozygous embryos expressing gyc76CWT in the muscle with twi-GAL4; mef2GAL4 (F), βPS is enriched at the MTJs (F′,F″, arrow) and is also found as intracellular puncta (F,F″, arrowhead). All embryos were stained for βPS (white) and F-actin (green) with embryos in A–C,F being additionally stained for β-gal. Embryos in A-E are at stage 16 whereas the embryo in F is at stage 15. Scale bar in A and A″ represents 5 µm.

Fig. 6. Quantification of βPS integrin levels at the MTJ.

The ratio of fluorescent intensity at the MTJ and cytoplasm of DO1/DA1 muscles was measured for stage 16 wild-type embryos, gyc76C2388 heterozygous and homozygous embryos and wild-type embryos expressing pkg21D RNAi in the muscle with twi-GAL4; mef2-GAL4. ** = p<0.001; *** = p<0.0001.

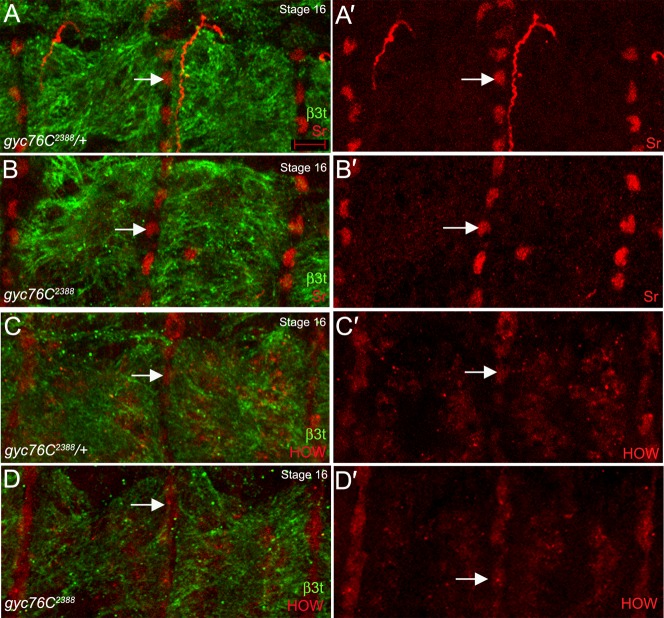

We confirmed that reduced βPS localization at MTJs in gyc76C2388 mutant embryos was not due to defects in specification or differentiation of tendon cells to which the dorsal muscles attach by staining for Stripe (Sr) and Held Out Wings (HOW) which label tendon cell precursors and differentiated tendon cells, respectively (Becker et al., 1997; Nabel-Rosen et al., 1999). In gyc76C2388 heterozygous and homozygous embryos, staining for Sr and HOW showed a similar number of tendon cells (Fig. 7A–D) demonstrating that the integrin localization defect observed in gyc76C2388 mutant embryos was not due to a failure in tendon cell specification or differentiation.

Fig. 7. Tendon cell specification is normal in gyc76C mutant embryos.

In gyc76C2388 heterozygous (A,C) and homozygous (B,D) embryos, tendon cells are specified as indicated by Stripe (Sr) expression (A,A′,B,B′, red, arrows) and differentiate as indicated by HOW expression (C,C′,D,D′, red, arrows). Embryos in A,B were stained for Sr (red) and in C,D for HOW (red) and all embryos were co-stained for β3t to label dorsal muscles and β-gal to distinguish heterozygous from homozygous embryos (not shown). All embryos shown are at stage 16. Scale bar in A represents 5 µm.

Discussion

In this study, we provide evidence for a novel role for Guanylyl cyclase at 76C (Gyc76C) in Drosophila somatic muscle development. We showed that gyc76C function is required in the somatic muscles for proper patterning and for localization of the βPS integrin subunit at the developing MTJs of the DO1/DA1 muscles. We also showed that the cGMP dependent protein kinase, DG1, is similarly required for muscle patterning and for integrin localization at the MTJ. The presence of unfused FCMs in gyc76C2388 homozygous embryos and pkg21D RNAi-treated embryos suggests a role for cGMP signaling in early stages of muscle development, such as myoblast fusion. In addition to myoblast fusion, gyc76C may have a role in myotube extension since we observed shortened ventral muscles in gyc76C mutant embryos. It is likely that the maternal contribution of gyc76C in gyc76C2388 mutant embryos allows sufficient patterning of the dorsal somatic muscles; however, it is not sufficient for proper localization of βPS integrin during MTJ formation. Therefore, our findings suggest that gyc76C and pkg21D regulate multiple stages of somatic muscle development.

Despite the significant role that integrins play in embryogenesis, little is known about how they are regulated. One mechanism for integrin control is through its turnover. It was first demonstrated in migrating mammalian cells that transient integrin-based adhesion to the ECM is achieved, at least in part, through the endocytosis and recycling of transmembrane integrins (Bretscher, 1989; Ezratty et al., 2005). More recently, it has been shown that integrin adhesion complexes at the Drosophila MTJ turnover in a clathrin- and Rab5-modulated process (Yuan et al., 2010) and that integrin trafficking is regulated at least in part by phosphoinositides (Ribeiro et al., 2011). Our observation that loss of gyc76C or pkg21D promotes accumulation of βPS integrin subunit in intracellular puncta suggests a defect in integrin transport to the MTJ and/or its retention at the MTJ. Interestingly, previous reports have linked cGMP-dependent protein kinase I to integrin-mediated adhesion in osteoclasts and pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells (Negash et al., 2009; Yaroslavskiy et al., 2005). Thus, guanylyl cylcases and downstream cGMP-signaling may play a conserved role in integrin mediated adhesion in multiple cell types.

cGMP signaling is known to play an important role in axon guidance (Song et al., 1998; Song and Poo, 1999). In the Drosophila embryo gyc76C is required for semaphorin-1a-plexin A-mediated repulsive guidance of motor axons (Ayoob et al., 2004). Although these studies showed that the cyclase activity of Gyc76C is important for axon repulsion, it is not known how signaling events downstream of Gyc76C directs the axonal response. Based on our studies, Gyc76C may regulate axon guidance by controlling integrin-mediated adhesion as it does in the muscle. In support of this, semaphorin-dependent control of cell migration is known to involve integrin-based adhesion (Pasterkamp and Kolodkin, 2003; Tamagnone and Comoglio, 2004; Tran et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2008).

Numerous studies identified a role for cGMP in cell migration and cytoskeletal remodeling. For example, elevation of cGMP levels disrupts actin stress fibers by cGK-dependent phosphorylation and inactivation of RhoA in vascular smooth muscle cells (Sauzeau et al., 2000), and during chemotaxis of Dictyostelium amoebae, cGMP activates myosin light chain kinase to induce myosin filament formation and suppress pseudopod formation at the rear of the migrating cell (Goldberg et al., 2006). More recently, mammalian receptor type GC was shown to be activated in a phosphorylation-independent manner by p21-activiated kinase (Pak), a downstream effector of Rac GTPase, and this Rac-Pak-GC pathway is important for PDGF-induced lamellipodial formation and migration of cultured mammalian cells (Guo et al., 2007). cGMP-dependent protein kinase is also known to activate Rac1 and Pak1 (Hou et al., 2004), suggesting a positive feed-back loop for regulation of cell migration by the Rac-Pak-cGMP signaling pathway. Additional studies are necessary to determine whether Gyc76C regulates muscle development and specifically, integrin localization at the MTJs, through one or more of these signaling components.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila strains and genetics

Canton-S flies were used as wild-type controls. The following fly lines were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center and are described in FlyBase (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu): Df(3L)fln1, Df(3L)XS533, Df(3L)e-19, Df(3L)kto2, Df(3L)ED4858, Df(3L)Exel9008, Df(3L)Exel9011, Df(3L)Exel9061, Df(3L)Exel9045and Df(3L)BSC1. gyc76C2388 was generated by standard EMS mutagenesis as previously described (Myat et al., 2005). PKGf05504 was obtained from the Exelixis collection at Harvard Medical School and is described in FlyBase. gyc76CEx173 and UAS-gyc76CWT lines were gifts from A. Kolodkin (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA). Generation of RNAi lines to pkg21D, for and gyc76C have been previously described (Overend et al., 2012; Vermehren-Schmaedick et al., 2010). Expression of pkg21D RNAi and gyc76C RNAi in Drosophila Malpighian tubules resulted in an approximate knockdown of 30% and 40%, respectively (S.A.D., unpublished). UAS- pkg21D RNAi line was also obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (Vienna, Austria). Using the UAS-GAL4 expression system (Brand and Perrimon, 1993), mef2-GAL4 and twi-GAL4 (gifts from M. Baylies [Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Institute, New York, NY USA]) were used to drive muscle-specific expression of wild-type gyc76C.

Mapping of gimli2388 mutation to gyc76C

The gimli2388 mutation was generated from a large scale EMS-mutagenesis screen for mutations affecting salivary gland and tracheal development (Myat et al., 2005). Complementation tests with 51 deficiency lines, which we previously reported to have salivary gland migration defects (Jattani et al., 2009), identified two that failed to complement the lethality of gimli2388, Df(3L)XS533 (deletes 76B04-77B) and Df(3L)e-19 (deletes 93B06-93D2). Embryos homozygous for Df(3L)XS533 or Df(3L)e-19 showed defects in gland invagination and migration (data not shown). Moreover, embryos trans-heterozygous for Df(3L)XS533 and gimli2388 showed a gland phenotype identical to that of Df(3L)XS533 homozygous embryos. Embryos trans-heterozygous for gimli2388 and Df(3L)e-19 did not show defects in gland development. Therefore, the gimli2388 mutant chromosome has two lethal mutations, one that maps in the 76B04-77B region and another in the 93B06-93D2 region. However, the lethal mutation at 93 did not contribute to the gland migration defect of gimli2388 and thus, the wild-type gene corresponding to gimli2388 gene resided in the 76B04-77B genomic interval. We segregated these two independent mutations through meiotic recombination with the rucuca chromosome. We mapped the gimli2388 mutation to a smaller interval within 76B04-77B by testing smaller overlapping deficiencies within these genomic regions for gland migration defects on their own and in-trans to gimli2388 (Table 1). We identified one deficiency, Df(3L)9061, that deletes the 76C2-76C3 genomic region that showed a strong salivary galnd migration defect when homozygous and in trans to gimli2388. Bi-directional sequencing of the gyc76C gene in gimli2388 mutant embryos revealed that the mutation in gyc76C is a single nucleotide change of T to G in the 5′ end of the intron sequence following exon 16 changing the conserved GU at the splice donor site to GG. This nucleotide change results in the insertion of 92 base pair sequences of intron 6 which contains an in-frame stop codon before the guanylyl cyclase domain.

Antibody staining of embryos

Embryo fixation and antibody staining were performed as previously described (Myat et al., 2005). The following antisera were used at the indicated dilutions: rabbit β3t antiserum (a gift from R. Renkawitz-Pohl, Philipps-University Marburg, Germany) at 1∶10,000; mouse βPS antiserum (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, DSHB; Iowa City, IA) at 1∶200; rabbit Tropomyosin (abCAM, Cambridge, MA) at 1∶1000; rat Kruppel antiserum at 1∶40 (a gift from S. Small, New York University, NY, USA); guinea pig Stripe and rat HOW antisera (gifts from Talila Volk, Weizmann Institute, Rehovot, Israel) at 1∶200 and 1∶100, respectively and mouse β-galactosidase (β-gal) antiserum (Promega, Madison, WI) at 1∶10,000 for DAB staining and 1∶500 for fluorescence staining. Appropriate biotinylated- (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Westgrove, PA), AlexaFluor 488-, 647- or Rhodamine- (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) conjugated secondary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1∶500. Whole-mount DAB stained embryos were mounted in methyl salicylate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and embryos were visualized on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope with Axiovision Rel 4.2 software (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Whole-mount immunofluorescence stained embryos were mounted in Aqua Polymount (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA) and thick (1 µm) fluorescence images were acquired on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with LSM 510 for laser scanning confocal microscopy at the Weill Cornell Medical College optical core facility (New York, NY).

RNA in situ hybridization

In situ hybridization (ISH) with antisense digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes for gyc76C was performed as previously described (Lehmann and Tautz, 1994). gyc76C cDNA was obtained from Open Biosystems and was used as a template for generating antisense digoxygenin-labeled RNA probes as previously described. Embryos were mounted in 70% glycerol before visualization as described above for whole mount antibody staining.

Quantification of βPS fluorescence intensity

Fluorescent intensity ratio between the MTJ and cytoplasm of the dorsal muscles was obtained using an established method (Pines et al., 2011). Specifically, Z-stack projections of approximately five 1-micron thick optical sections through the MTJ of DO1/DA1 muscles of at least seven representative embryos of each genotype immunolabeled with βPS and F-actin were selected for morphometric analysis. Three MTJs between abdominal segments 1 and 6 per embryo were selected for quantification. Fluorescent intensity within an area of approximately 2 µm2 (0.5×4) in the central region of the MTJ and a region of the exact size in the cytoplasm close to the MTJ of the DO1/DA1 muscle was measured using Image J software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD) and its ratio (MTJ/Cyto) calculated. Identifical parameters were used for image acquisition and fluorescent intensity measurements in all genotypes analyzed. Statistical analysis was done using Microsoft Excel.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to M. Baylies, A. Kolodkin, R. Renkawitz-Pohl, S. Small and T. Volk for providing antisera and fly lines. We also thank the Bloomington Stock Center, Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center, Harvard Medical School and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for providing fly lines and antisera that made this work possible. We are grateful to Mary Baylies, Frieder Schoeck and members of the Myat lab for providing valuable insight and discussions during the course of these studies and for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank the Weill Cornell Medical College optical core facility. This work was supported by NIH grant GM082996 to M.M.M.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

References

- Ayoob J. C., Yu H. H., Terman J. R., Kolodkin A. L. (2004). The Drosophila receptor guanylyl cyclase Gyc76C is required for semaphorin-1a-plexin A-mediated axonal repulsion. J. Neurosci. 24, 6639–6649 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1104-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate M. (1990). The embryonic development of larval muscles in Drosophila. Development 110, 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylies M. K., Bate M., Ruiz Gomez M. (1998). Myogenesis: a view from Drosophila. Cell 93, 921–927 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81198-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker S., Pasca G., Strumpf D., Min L., Volk T. (1997). Reciprocal signaling between Drosophila epidermal muscle attachment cells and their corresponding muscles. Development 124, 2615–2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckett K., Baylies M. K. (2006). The development of the Drosophila larval body wall muscles. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 75, 55–70 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)75003-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bökel C., Brown N. H. (2002). Integrins in development: moving on, responding to, and sticking to the extracellular matrix. Dev. Cell 3, 311–321 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00265-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boube M., Martin-Bermudo M. D., Brown N. H., Casanova J. (2001). Specific tracheal migration is mediated by complementary expression of cell surface proteins. Genes Dev. 15, 1554–1562 10.1101/gad.195501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabant M. C., Brower D. L. (1993). PS2 integrin requirements in Drosophila embryo and wing morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 157, 49–59 10.1006/dbio.1993.1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley P. L., Myat M. M., Comeaux C. A., Andrew D. J. (2003). Posterior migration of the salivary gland requires an intact visceral mesoderm and integrin function. Dev. Biol. 257, 249–262 10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00103-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A. H., Perrimon N. (1993). Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118, 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher M. S. (1989). Endocytosis and recycling of the fibronectin receptor in CHO cells. EMBO J. 8, 1341–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. H. (1994). Null mutations in the αPS2 and βPS integrin subunit genes have distinct phenotypes. Development 120, 1221–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. H., Gregory S. L., Martin-Bermudo M. D. (2000). Integrins as mediators of morphogenesis in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 223, 1–16 10.1006/dbio.2000.9711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintapalli V. R., Wang J., Dow J. A. (2007). Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat. Genet. 39, 715–720 10.1038/ng2049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S. A. (2006). Signalling via cGMP: lessons from Drosophila. Cell. Signal. 18, 409–421 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S. A., Day J. P. (2006). cGMP signalling in a transporting epithelium. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34, 512–514 10.1042/BST0340512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezratty E. J., Partridge M. A., Gundersen G. G. (2005). Microtubule-induced focal adhesion disassembly is mediated by dynamin and focal adhesion kinase. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 581–590 10.1038/ncb1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasch M. (1999). Controls in patterning and diversification of somatic muscles during Drosophila embryogenesis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 9, 522–529 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)00014-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigliotti S., Cavaliere V., Manzi A., Tino A., Graziani F., Malva C. (1993). A membrane guanylate cyclase Drosophila homolog gene exhibits maternal and zygotic expression. Dev. Biol. 159, 450–461 10.1006/dbio.1993.1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg J. M., Wolpin E. S., Bosgraaf L., Clarkson B. K., Van Haastert P. J., Smith J. L. (2006). Myosin light chain kinase A is activated by cGMP-dependent and cGMP-independent pathways. FEBS Lett. 580, 2059–2064 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D., Tan Y. C., Wang D., Madhusoodanan K. S., Zheng Y., Maack T., Zhang J. J., Huang X. Y. (2007). A Rac-cGMP signaling pathway. Cell 128, 341–355 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y. K., Chou F.-L., Engvall E., Ogawa M., Matsuda C., Hirabayashi S., Yokochi K., Ziober B. L., Kramer R. H., Kaufman S. J. et al. (1998). Mutations in the integrin α7 gene cause congenital myopathy. Nat. Genet. 19, 94–97 10.1038/ng0598-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y., Ye R. D., Browning D. D. (2004). Activation of the small GTPase Rac1 by cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Cell. Signal. 16, 1061–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R. O. (2002). Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110, 673–687 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00971-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jattani R., Patel U., Kerman B., Myat M. M. (2009). Deficiency screen identifies a novel role for beta 2 tubulin in salivary gland and myoblast migration in the Drosophila embryo. Dev. Dyn. 238, 853–863 10.1002/dvdy.21899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann R., Tautz D. (1994). In situ hybridization to RNA. Methods Cell Biol. 44, 575–598 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)60933-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Yoon J., Burg M., Chen L., Pak W. L. (1995). Molecular characterization of two Drosophila guanylate cyclases expressed in the nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 12418–12427 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas K. A., Pitari G. M., Kazerounian S., Ruiz-Stewart I., Park J., Schulz S., Chepenik K. P., Waldman S. A. (2000). Guanylyl cyclases and signaling by cyclic GMP. Pharmacol. Rev. 52, 375–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson M. R., Lohmann S. M., Davies S. A. (2004). Analysis of Drosophila cGMP-dependent protein kinases and assessment of their in vivo roles by targeted expression in a renal transporting epithelium. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40026–40034 10.1074/jbc.M405619200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Bermudo M. D., Brown N. H. (1996). Intracellular signals direct integrin localization to sites of function in embryonic muscles. J. Cell Biol. 134, 217–226 10.1083/jcb.134.1.217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Bermudo M. D., Alvarez-Garcia I., Brown N. H. (1999). Migration of the Drosophila primordial midgut cells requires coordination of diverse PS integrin functions. Development 126, 5161–5169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil L., Chinkers M., Forte M. (1995). Identification, characterization, and developmental regulation of a receptor guanylyl cyclase expressed during early stages of Drosophila development. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 7189–7196 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton D. B. (2004). Invertebrates yield a plethora of atypical guanylyl cyclases. Mol. Neurobiol. 29, 97–116 10.1385/MN:29:2:097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton D., Hudson M. (2002). Cyclic GMP regulation and function in insects. Adv. Insect Physiol. 29, 1–54 10.1016/S0065-2806(02)29001-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myat M. M., Lightfoot H., Wang P., Andrew D. J. (2005). A molecular link between FGF and Dpp signaling in branch-specific migration of the Drosophila trachea. Dev. Biol. 281, 38–52 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabel-Rosen H., Dorevitch N., Reuveny A., Volk T. (1999). The balance between two isoforms of the Drosophila RNA-binding protein how controls tendon cell differentiation. Mol. Cell 4, 573–584 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80208-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negash S., Narasimhan S. R., Zhou W., Liu J., Wei F. L., Tian J., Raj J. U. (2009). Role of cGMP-dependent protein kinase in regulation of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell adhesion and migration: effect of hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297, H304–H312 10.1152/ajpheart.00077.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S. M., Jr and Wright T. R. (1981). A histological and ultrastructural analysis of developmental defects produced by the mutation, lethal(1)myospheroid, in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Biol. 86, 393–402 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90197-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overend G., Cabrero P., Guo A. X., Sebastian S., Cundall M., Armstrong H., Mertens I., Schoofs L., Dow J. A. T., Davies S.-A. (2012). The receptor guanylate cyclase Gyc76C and a peptide ligand, NPLP1-VQQ, modulate the innate immune IMD pathway in response to salt stress. Peptides 34, 209–218 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasterkamp R. J., Kolodkin A. L. (2003). Semaphorin junction: making tracks toward neural connectivity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 13, 79–89 10.1016/S0959-4388(03)00003-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer A., Aszódi A., Seidler U., Ruth P., Hofmann F., Fässler R. (1996). Intestinal secretory defects and dwarfism in mice lacking cGMP-dependent protein kinase II. Science 274, 2082–2086 10.1126/science.274.5295.2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines M., Fairchild M. J., Tanentzapf G. (2011). Distinct regulatory mechanisms control integrin adhesive processes during tissue morphogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 240, 36–51 10.1002/dvdy.22488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokop A., Martín-Bermudo M. D., Bate M., Brown N. H. (1998). Absence of PS integrins or laminin A affects extracellular adhesion, but not intracellular assembly, of hemiadherens and neuromuscular junctions in Drosophila embryos. Dev. Biol. 196, 58–76 10.1006/dbio.1997.8830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro I., Yuan L., Tanentzapf G., Dowling J. J., Kiger A. (2011). Phosphoinositide regulation of integrin trafficking required for muscle attachment and maintenance. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001295 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roote C. E., Zusman S. (1995). Functions for PS integrins in tissue adhesion, migration, and shape changes during early embryonic development in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 169, 322–336 10.1006/dbio.1995.1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Gómez M., Romani S., Hartmann C., Jäckle H., Bate M. (1997). Specific muscle identities are regulated by Krüppel during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development 124, 3407–3414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauzeau V., Le Jeune H., Cario-Toumaniantz C., Smolenski A., Lohmann S. M., Bertoglio J., Chardin P., Pacaud P., Loirand G. (2000). Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase signaling pathway inhibits RhoA-induced Ca2+ sensitization of contraction in vascular smooth muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 21722–21729 10.1074/jbc.M000753200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schejter E. D., Baylies M. K. (2010). Born to run: creating the muscle fiber. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 566–574 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnorrer F., Dickson B. J. (2004). Muscle building: mechanisms of myotube guidance and attachment site selection. Dev. Cell 7, 9–20 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R., Zelzer E., Volk T. (2010). Connecting muscles to tendons: tendons and musculoskeletal development in flies and vertebrates. Development 137, 2807–2817 10.1242/dev.047498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H. J., Poo M. M. (1999). Signal transduction underlying growth cone guidance by diffusible factors. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 9, 355–363 10.1016/S0959-4388(99)80052-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H., Ming G., He Z., Lehmann M., McKerracher L., Tessier-Lavigne M., Poo M. (1998). Conversion of neuronal growth cone responses from repulsion to attraction by cyclic nucleotides. Science 281, 1515–1518 10.1126/science.281.5382.1515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamagnone L., Comoglio P. M. (2004). To move or not to move? Semaphorin signalling in cell migration. EMBO Rep. 5, 356–361 10.1038/sj.embor.7400114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran T. S., Kolodkin A. L., Bharadwaj R. (2007). Semaphorin regulation of cellular morphology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 263–292 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010605.093554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermehren-Schmaedick A., Ainsley J. A., Johnson W. A., Davies S. A., Morton D. B. (2010). Behavioral responses to hypoxia in Drosophila larvae are mediated by atypical soluble guanylyl cyclases. Genetics 186, 183–196 10.1534/genetics.110.118166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaroslavskiy B. B., Zhang Y., Kalla S. E., García Palacios V., Sharrow A. C., Li Y., Zaidi M., Wu C., Blair H. C. (2005). NO-dependent osteoclast motility: reliance on cGMP-dependent protein kinase I and VASP. J. Cell Sci. 118, 5479–5487 10.1242/jcs.02655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L., Fairchild M. J., Perkins A. D., Tanentzapf G. (2010). Analysis of integrin turnover in fly myotendinous junctions. J. Cell Sci. 123, 939–946 10.1242/jcs.063040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Gunput R. A., Pasterkamp R. J. (2008). Semaphorin signaling: progress made and promises ahead. Trends Biochem. Sci. 33, 161–170 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]