Summary

Non-coding microRNA (miRNA) molecules bind their target mRNAs and thereby modulate the amount of protein produced. To understand the significance of a potential miRNA-mRNA interaction, temporal and spatial information on miRNA and mRNA expression is essential. Here, we provide a detailed protocol for miRNA whole mount in situ hybridization. We introduce the use of Morpholino based oligos as antisense probes for miRNA detection, in addition to the current “gold standard” locked nucleic acid (LNA) probes. Furthermore we have modified existing miRNA in situ protocols thereby improving both sensitivity and resolution of miRNA visualization in whole zebrafish embryos and adult tissues.

Keywords: MicroRNA, in situ hybridization, Zebrafish

Introduction

Since the discovery of the first regulating small RNAs (later classified as microRNAs), lin-4 and let-7, in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (Lee et al., 1993; Reinhart et al., 2000), ongoing high throughput cloning approaches have led to the discovery of hundreds of miRNAs. MiRNAs inhibit protein expression by binding mainly to 3′UTR sequences of messenger RNA molecules (reviewed by Bartel, 2009). Functional studies thus far have implicated miRNAs to function in various processes during embryonic development and disease (reviewed by Hagen and Lai, 2008). Since miRNAs do not translate into protein, the identification of the tissues and cell types in which specific miRNAs are expressed relies heavily on in situ hybridization detection techniques. To date, LNA probes complementary to mature miRNA sequences are the most commonly used oligos for miRNA detection from various species for in situ hybridization as well as for probing miRNAs on microarray platforms (Ason et al., 2006; Darnell et al., 2006; Kloosterman et al., 2006; Obernosterer et al., 2007; Mishima et al., 2009; Pase et al., 2009; Pena et al., 2009; Goljanek-Whysall et al., 2011; Preis et al., 2011). Nevertheless, alternatives for LNA based probes have been reported (Søe et al., 2011).

Current miRNA in situ hybridization protocols provide limited spatial resolution of low-abundant miRNAs. Diffusion of small miRNAs into the tissue after formaldehyde fixation has been suggested to cause these limitations in spatial resolution (Pena et al., 2009). We have applied 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyl-aminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) fixation on zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos and adult zebrafish tissues. EDC crosslinks the 5′-phosphate of miRNAs, which is formed during miRNA maturation, to amino groups in the protein matrix. Here, we present a miRNA whole mount in situ hybridization method allowing a sensitive detection with high spatial resolution of miRNAs expression in both zebrafish embryos and adult tissues.

Materials and Methods

A step-by-step protocol with a summary of required materials, details on reagent preparation and additional procedures are available at http://www.hubrecht.eu/research/bakkers/protocols.html and we strongly recommend that these data are consulted in combination with the information provided below.

Embryonic and adult tissue preparation

Paraformaldehyde fixation

Zebrafish embryos were staged live and subsequently fixed in PFA1 (4% paraformaldehyde, 4% sucrose in PBS), overnight (o/n) at 4°C in 4 ml glass vials on a 3D rocker.

Adult zebrafish tissues were dissected and fixed in PFA1 for 48 hours at 4°C, while on a 3D rocker.

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyl-aminopropyl) carbodiimide fixation

PFA1 fixed embryos and adult tissues were washed three times in PBS containing 0.01% Tween-20 (PBS-T) at room temperature (RT), for 10 min on a 3D rocker to remove residual PFA1. Subsequently, all samples were washed three times in fresh 1-methylimidazole buffer (1-MIB) (1% 1-methylimidazole, 300 mM NaCl in water pH 8.0 (HCl)) for 15 min while on a 3D rocker at RT. Next, embryos were fixed in fresh 0.16 M 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyl-aminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) diluted in 1-MIB (pH 8.0). Upon addition of EDC fixative embryos were first fixed for 2 hours at RT followed by o/n fixation at 4°C, while on a 3D rocker. Adult hearts and fins were incubated in 0.16M EDC for 2 hours at RT followed by 48 hours at 4°C, while on a 3D rocker.

After EDC fixation embryos and adult tissues were washed three times in PBS-T at RT for 10 min while on a 3D rocker to remove residual EDC.

Dehydration

Embryos and adult tissues were dehydrated through a series of methanol (MeOH) diluted in PBS-T (25% MeOH, 50% MeOH, 75% MeOH, 100% MeOH) at RT for 10 min (embryos) or 20 min (adult tissues) per solution. The last step (100% MeOH) was repeated once, after which embryos and adult tissues were stored at −20°C until further use. However, when an in situ hybridization procedure was initiated on the same day after dehydration, embryos and adult tissues were first incubated in the final 100% MeOH solution at RT for at least two hours to ensure full dehydration of the embryos.

All dehydration washes were performed on a 3D rocker. Embryos remained in 4 ml glass screw top vials and adult tissues in 10 ml plastic screw top tubes.

MicroRNA in situ hybridization

Rehydration

Dehydrated embryos stored in 100% MeOH at −20°C were divided per sample into 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes (<30 embryos). Adult tissues were divided into 2 ml Eppendorf tubes (<5 hearts, <3 fins). Samples were re-hydrated through a series of MeOH in PBS-T (75% MeOH, 50% MeOH, 25% MeOH). Samples were washed (embryos 10 min, tissue 20 min) in each solution, while on a 3D rocker at RT. Afterwards samples were placed in PBS-T and washed four times in PBS-T while on a 3D rocker for 10 min per wash at RT (embryos and adult tissue).

Proteinase K treatment

After the re-hydration all samples were treated with proteinase K to facilitate infiltration of the probes into the tissue. Proteinase K treatment should be optimised for the embryonic stage, type of tissue used and when using a new batch of enzyme. We have listed an overview of the concentrations, incubation times and temperatures we used in supplementary material Table S1. Embryos were incubated in 1.5 ml tubes containing 500 µl proteinase K (10 µg/ml) diluted in PBS-T. Adult tissues were incubated in 1 ml proteinase K solution in 2 ml tubes. Samples should not move during the proteinase K treatment.

After proteinase K treatment embryos and adult tissues were re-fixed in 4% PFA2 (4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4) for 10 min (embryos and adult tissue) at RT. Following re-fixation samples were washed five times for 10 min per wash in PBS-T at RT.

Hybridization

Next, PBS-T was replaced by hybridization buffer (HYB-, 50% deionized formamide, 5× saline sodium citrate (SSC), 0.1% Tween-20, 9.2 mM citric acid) supplemented with 50 µg/ml Heparin and 0.5 mg/ml tRNA (HYB+) (500 μl HYB+ for embryos (1.5 ml tube) and adult hearts (2 ml tube), 1 ml HYB+ for adult fins (2 ml tube)). All samples were placed in heat blocks or water baths to pre-hybridize for minimally 2 hours at the corresponding hybridization temperature (supplementary material Table S2). Subsequently, samples were incubated o/n with probes diluted in HYB+ at the corresponding hybridization temperature. For embryos in 1.5 ml tubes and adult hearts in 2 ml tubes we use 500 μl of probe dilution. For caudal fins in 2 ml tubes we used 1 ml of probe dilution.

After o/n probe hybridization, samples were washed once in pre-heated HYB- for 10 min at the probe hybridization temperature. Afterwards, all samples are taken through a series of pre-heated HYB- diluted in 2× SSC-T (SSC containing 0.01% Tween-20), first 75% HYB-/2×SSC-T, then 50% HYB-/2×SSC-T and finally 25% HYB-/2×SSC-T. For each step during this series, embryos and adult tissues were incubated for 15 min at the probe hybridization temperature. Afterwards, all samples were incubated 15 min in pre-heated 2×SSC-T at the hybridization temperature followed by two 30 min incubations in pre-heated 0.2×SSC-T at the hybridization temperature. All samples were subsequently taken through a graded series of 0.2×SSC-T diluted in PBS-T, first 75% 0.2×SSC-T/PBS-T, then 50% 0.2×SSC-T/PBS-T and finally 25% 0.2×SSC-T/PBS-T, all at RT. All samples were subsequently washed twice in PBS-T at RT for 10 min before being transferred to blocking buffer (BB, 2% sheep serum, 2 mg/ml BSA in PBS-T) for minimally 1 hour at RT while on a 3D rocker. After blocking, all samples were incubated o/n in BB containing either pre-incubated anti-digoxigenin (Roche, 1:5000) or anti-fluorescein (Roche, 1:5000) antibodies while on a 3D rocker at 4°C (embryos in 0.5 ml Eppendorf tubes with 300 µl antibody dilution, adult tissues in 2 ml tubes with 2 ml antibody solution).

Staining

After o/n incubation the antibody dilution was removed from all samples and replaced by PBS-T, followed by two quick washes with PBS-T for 5 min per wash at RT. Hereafter samples were washed six times with PBS-T for 15 min per wash while on a 3D rocker at RT. Subsequently, all samples were washed three times in staining buffer (SB, 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 9.5, 50 mM Mg2Cl, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.01% Tween-20) at RT while on a 3D rocker, once for 5 min and twice for 15 min. For the staining procedure all embryonic samples were transferred to 24-well plates and adult tissues to 6 well plates and incubated with 500 µl (embryos) or 4 ml (adult tissues) SB supplemented with NBT (Roche, 1:200) and BCIP (Roche, 1:270) at RT. The staining intensity was monitored using a stereomicroscope with top light while placing the plate on a white background. During staining the plates were wrapped in aluminium foil to ensure darkness during staining. For most miRNAs probes used, we performed the staining o/n at RT. For PFA fixed samples, ubiquitous non-specific background staining will develop alongside miRNA specific staining therefore o/n staining will generally result in the most optimal signal. When staining PFA fixed samples longer the background will disturb the actual miRNA specific signal. PFA+EDC fixed samples will develop specific miRNA signal without additional non-specific background when stained o/n and therefore can be stained for up to several days. For a direct comparison of the two fixation methods, the staining solution was removed after approximately 24 hours when the most satisfactory staining was obtained using both methods. Once satisfactory staining was obtained the staining solution was removed completely and samples were washed three times in PBS-T for 5 min per wash while remaining in the wells. Finally samples were fixed in 4% PFA2 o/n at 4°C in the plates.

Visualization

After o/n fixation, PFA2 was replaced by PBS-T. Embryos or adult hearts were transferred to 1.5 ml screw top tubes (polypropylene) while caudal fins were transferred to 2 ml tubes (Eppendorf). All samples were washed two times in PBS-T at RT while on a 3D rocker. Subsequently, samples were dehydrated through a series of methanol (MeOH) diluted in PBS-T (25% MeOH, 50% MeOH, 75% MeOH, 100% MeOH) at RT while on a 3D rocker for 10 min (embryos) or 20 min (adult tissues) per solution. Dehydration was followed by two washes in 100% MeOH for at least 30 min each to ensure all residual PBS-T was removed. Finally the MeOH was replaced by Murray's solution (benzylbenzoate:benzylalcohol 2:1). The Murray's solution clears the tissue and can be used for long-term storage of the samples at 4°C in the dark in polypropylene tubes. Imaging of the miRNA expression pattern was performed in Murray's solution after an o/n incubation at 4°C.

Antisense probes

All LNA probes (Exiqon) were diluted in milli-Q water to a stock concentration of 10 µM and stored at −80°C. The double Digoxigenin labelled (3′ and 5′) miR-23 LNA probe (Exiqon) was diluted 700 times in hybridization buffer as a working dilution. All other LNA oligonucleotides were labelled with digoxigenin-11-ddUTP (Roche) at the 3′ end using a terminal transferase kit (Roche) and purified using MicroSpinTM G-25 Columns (Amersham Biosciences). Single 3′ end labelled LNA probes were diluted 200 times in hybridization buffer (HYB+) as a working dilution.

Carboxyfluorescein (CF)-labelled Morpholino oligos (MO) (Gene Tools) were diluted in milli-Q water to a stock concentration of 1 mM and stored at −20°C. All CF-labelled MO probes were diluted 50,000 times in HYB+ as a working dilution. All LNA and MO probe dilutions were re-used up to 10 times.

Morpholino injections

MiR-23 MO (Gene Tools) was diluted and injected as described previously (Lagendijk et al., 2011). Sequence of the CF-labelled miR-124 MO used for miR-124 knock-down was as follows:

CF-labelled miR-124 MO: 5′- tggcattcaccgcgtgccttaa -3′

For injection, the CF-labelled miR-124 MO was diluted to 0.2 mM, of which 1 nl was injected at the one cell stage.

Antibody staining and sectioning

Tropomyosin antibody staining and subsequent plastic sectioning of miR-23 in situ stained embryos was performed as described previously (Lagendijk et al., 2011).

Results and Discussion

Morpholino oligomers detect miRNA expression by whole mount in situ hybridisation

While LNA oligos are widely used as antisense probes to detect miRNA expression, their use as knock-down reagent in zebrafish is less versatile (Kloosterman et al., 2007). Morpholino oligos (MO) have been shown to bind miRNAs with high affinity in vivo resulting in efficient knock-down of miRNA expression in zebrafish embryos (Kloosterman et al., 2007), however their use as antisense probes had not been reported. Therefore we used carboxyfluorescein(CF)-labelled MOs, overlapping with the mature miRNA sequences of different miRNAs, as miRNA probes. In situ hybridisation on 4 day old zebrafish larvae using these CF-labelled MOs as probes and anti-fluorescein antibodies for signal amplification and detection resulted in specific staining patterns (Fig. 1A–D). The observed staining patterns were indistinguishable from previously published patterns using LNA probes (Wienholds et al., 2005; Kloosterman et al., 2006). Next we investigated whether a CF-labelled MO could still function as a knock-down reagent. Therefore we performed miR-124 in situ hybridization on embryos previously injected by CF-labelled MO complementary to miR-124. As a result we observed a loss of mature miR-124 expression (supplementary material Fig. S1) demonstrating that CF-labelled MOs can still function as miRNA knock-down reagents. To summarize, we conclude that CF-labelled MOs targeting miRNAs can be used for both miRNA detection and knock-down purposes. Since many researchers already have Morpholino oligos in-hand for their knockdown experiments, it would be both convenient and economical to be able to use these same oligos for both knockdown and in situ hybridization.

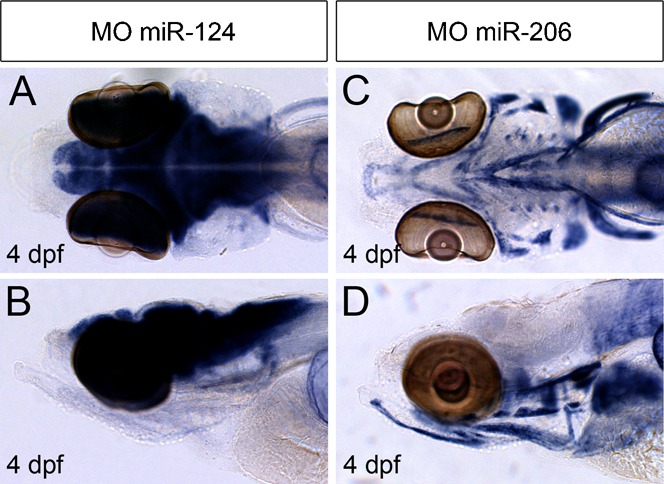

Fig. 1. Whole mount miRNA in situ hybridization by CF-labeled MO probes.

(A–B) In situ hybridization using a CF-labeled miR-124 MO probe on PFA fixed 4 dpf embryo detects expression in developing brain and eyes (A, dorsal view; B, lateral view). (C–D) In situ hybridization using a CF-labeled miR-206 MO probe on PFA fixed 4 dpf embryo detects expression of miR-206 in skeletal muscle cells (C, dorsal view; D, lateral view).

Whole mount EDC fixation improves sensitivity and spatial resolution in miRNA detection

Both LNA- and MO- based probes allow detection of robust miRNA expression in whole mount zebrafish embryos of late developmental stages (Fig. 1) (Wienholds et al., 2005; Kloosterman et al., 2006). However, their use in detecting low-abundance miRNA expression, such as during early stages of embryo development, can be hampered by the appearance of non-specific background signals. Fixation of paraffin sections in 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyl-aminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) has been reported to prevent miRNA diffusion by crosslinking miRNA 5′ends with amino groups in the protein matrix and thereby improving spatial resolution (Pena et al., 2009). To investigate whether EDC fixation could improve detection and spatial resolution of miRNA expression signals in whole mount in situ hybridization we compared fixation of zebrafish embryos in PFA with PFA+EDC. We used both digoxigenin (DIG) labelled LNA based probes as well as CF-labelled MO based probes to detect miRNAs at various developmental stages. In all cases we observed that embryos fixed in PFA+EDC showed a significant improvement in spatial resolution of the miRNA expression pattern when compared to PFA fixation alone (Fig. 2A–R). Non-specific background staining was very low in PFA+EDC fixed embryos, allowing the detection of specific expression patterns not observed with PFA fixation alone (Fig. 2, arrowheads). Together, these results demonstrate that the combination of both EDC and PFA fixation results in a robust improvement in spatial resolution and sensitivity of miRNA expression detection by whole mount in situ hybridization.

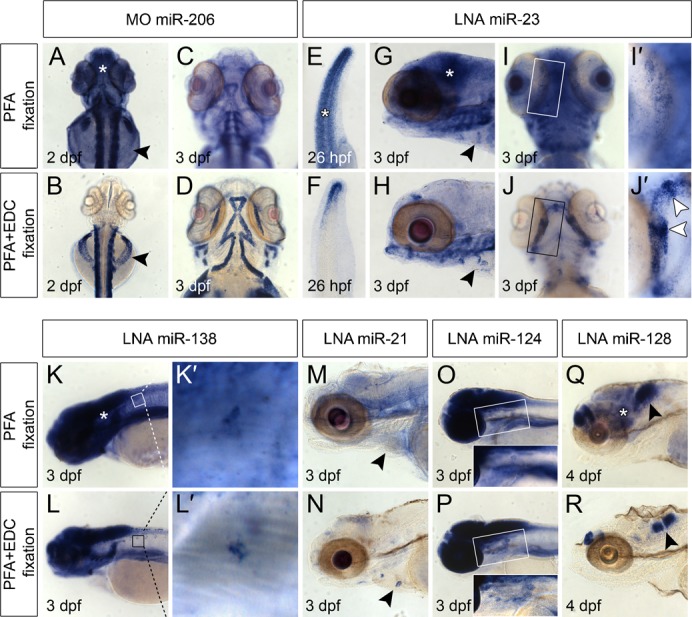

Fig. 2. Whole mount miRNA in situ hybridization on embryos.

Top rows of top and bottom panel: miRNA in situ hybridization on embryos fixed in PFA only. Bottom rows of top and bottom panel: miRNA expression detected in embryos fixed in PFA+EDC. All embryos where processed simultaneously and stained for approximately 24 h. All arrowheads indicate miRNA expression detectable with high resolution in PFA+EDC fixed samples versus fixation in PFA only. Asterisks indicate non-specific background signals in PFA fixed embryos (A,E,G,K,Q). (A–D) MiR-206 expression in skeletal muscle cells was detected by a CF-labeled MO probe at 2 dpf (A,B) and 3 dpf (C,D). Arrowheads (A,B) point to skeletal muscle cells located on the yolk that were detectable in PFA+EDC fixed embryos (B) and not in PFA fixed embryos (A). (E–J′) MiR-23 is expressed in the tail tip at 26 hpf (E–F), in the cardiac cushions at 3 dpf (G,H, arrowheads) and in developing bone structures of the jaw at 3 dpf (I–J′). (I′–J′) Magnification of boxed areas in I and J show enhanced miR-23 expression in future joints (arrowheads in J′), which was not detectable in PFA fixed embryos (I′). (K–L′) miR-138 is expressed in the developing brain (K,L) and motor neurons (K′,L′). (M,N) MiR-21 is expressed in cardiac cushions (arrowheads) at 3 dpf in PFA+EDC fixed embryo (N), which was not detectable in PFA fixed embryos (M). (O,P) Expression of miR-124 at 3 dpf in the brain and motor neurons located ventrally of the developing brain (boxed area) is hardly detectable in PFA fixed embryos (O) while clearly visible in PFA+EDC fixed embryos (P). (Q,R) Highly specific expression of miR-128 in two separated regions of the developing brain is seen in PFA+EDC fixed embryos at 4 dpf (arrowhead in R) compared to more diffuse staining in PFA fixed embryos (arrowhead in Q).

To verify whether the observed staining pattern in PFA+EDC fixed embryos resulted from specific miRNA expression, we performed a similar miRNA in situ hybridization analysis on embryos in which production of the mature miRNA was blocked. Indeed all miR-23 signals were lost in embryos injected with an antisense MO targeting miR-23 (supplementary material Fig. S2a,b). In addition, we tested whether it was possible to perform immunohistochemistry on embryos that had been processed for PFA+EDC fixation and in situ hybridization. Using an α-tropomyosin antibody we observed robust levels of tropomyosin in the myocardium of PFA+EDC fixed embryos processed for in situ hybridization prior to the immunohistochemistry procedure (supplementary material Fig. S2c).

EDC fixation reveals specific miRNA expression in adult zebrafish tissues

MiRNA expression studies in adult tissues are mostly performed by in situ hybridization on paraffin embedded sections (Obernosterer et al., 2006; Obernosterer et al., 2007; Pena et al., 2009). Here we investigated whether EDC fixation would allow detection of miRNA expression by whole mount in situ hybridization on adult tissues. We used adult zebrafish hearts and caudal fins and observed a specific staining pattern for miR-23 in PFA+EDC fixed tissues, which was reduced or absent in PFA fixed tissues (Fig. 3A–F). The specific staining pattern in adult hearts was not detected in control hearts that were not incubated with a probe (Fig. 3G). The application of whole mount in situ hybridization for the detection of miRNA expression in adult tissues will be a valuable new tool to address the function of miRNAs during tissue regeneration and disease.

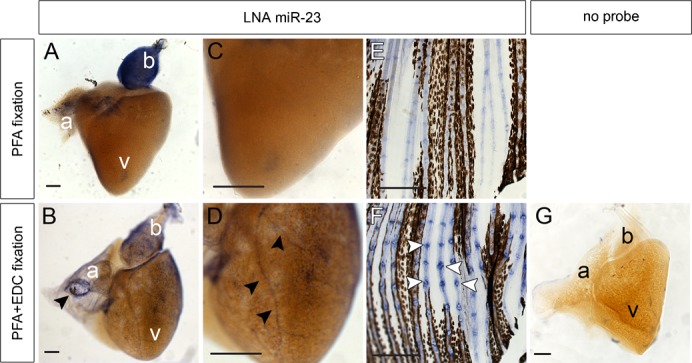

Fig. 3. Whole mount miRNA in situ hybridization on adult tissues.

(A–D) MiR-23 is expressed in the bulbus arteriosus (b) of zebrafish adult hearts fixed in PFA (A,C) and PFA+EDC (B–D). PFA+EDC fixed hearts revealed a more detailed miR-23 expression pattern with a ring-like expression (arrowhead in B) at the inflow area of the atrium (a) and in coronary arteries (arrowheads in D) overlying the ventricle (v). (E,F) Robust miR-23 expression was detected in joint structures of PFA+EDC fixed caudal fins (arrowheads in F) versus more diffuse miR-23 expression in caudal fins fixed in PFA only (E). (G) Negative control heart was fixed in PFA+EDC but not incubated with a probe. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

In conclusion we have optimised a method for whole mount in situ hybridization to detect non-coding miRNAs in zebrafish embryos and adult tissues. First we have shown that MO based probes can be used as an alternative for LNA based probes. This allows the use of a single CF-labelled MO as an antisense probe for in situ hybridization and as a knock-down reagent. Second we have applied EDC fixation to improve sensitivity and spatial resolution of the whole mount in situ hybridisation method.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wigard Kloosterman and members of the Bakker's laboratory for their suggestions during this work, and Gilbert Weidinger and Leonie Huitema for their judgment on some of the expression patterns. A.K.L. was supported by a Concordia fellowship by stichting vrienden van het Hubrecht. Research in J.B.'s laboratory was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO/ALW) grant 864.08.009.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Jon D. Moulton is employed by Gene Tools LLC and stands to profit by increased demand for Morpholino oligos. The other authors do not declare any competing interests.

References

- Ason B., Darnell D. K., Wittbrodt B., Berezikov E., Kloosterman W. P., Wittbrodt J., Antin P. B., Plasterk R. H. (2006). Differences in vertebrate microRNA expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 14385–14389 10.1073/pnas.0603529103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel D. P. (2009). MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136, 215–233 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell D. K., Kaur S., Stanislaw S., Konieczka J. H., Yatskievych T. A., Antin P. B. (2006). MicroRNA expression during chick embryo development. Dev. Dyn. 235, 3156–3165 10.1002/dvdy.20956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goljanek-Whysall K., Sweetman D., Abu-Elmagd M., Chapnik E., Dalmay T., Hornstein E., Münsterberg A. (2011). MicroRNA regulation of the paired-box transcription factor Pax3 confers robustness to developmental timing of myogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 11936–11941 10.1073/pnas.1105362108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen J. W., Lai E. C. (2008). microRNA control of cell-cell signaling during development and disease. Cell Cycle 7, 2327–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman W. P., Wienholds E., de Bruijn E., Kauppinen S., Plasterk R. H. (2006). In situ detection of miRNAs in animal embryos using LNA-modified oligonucleotide probes. Nat. Methods 3, 27–29 10.1038/nmeth843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman W. P., Lagendijk A. K., Ketting R. F., Moulton J. D., Plasterk R. H. (2007). Targeted inhibition of miRNA maturation with morpholinos reveals a role for miR-375 in pancreatic islet development. PLoS Biol. 5, e203 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagendijk A. K., Goumans M. J., Burkhard S. B., Bakkers J. (2011). MicroRNA-23 restricts cardiac valve formation by inhibiting Has2 and extracellular hyaluronic acid production. Circ. Res. 109, 649–657 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. C., Feinbaum R. L., Ambros V. (1993). The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75, 843–854 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima Y., Abreu-Goodger C., Staton A. A., Stahlhut C., Shou C., Cheng C., Gerstein M., Enright A. J., Giraldez A. J. (2009). Zebrafish miR-1 and miR-133 shape muscle gene expression and regulate sarcomeric actin organization. Genes Dev. 23, 619–632 10.1101/gad.1760209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obernosterer G., Leuschner P. J., Alenius M., Martinez J. (2006). Post-transcriptional regulation of microRNA expression. RNA 12, 1161–1167 10.1261/rna.2322506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obernosterer G., Martinez J., Alenius M. (2007). Locked nucleic acid-based in situ detection of microRNAs in mouse tissue sections. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1508–1514 10.1038/nprot.2007.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pase L., Layton J. E., Kloosterman W. P., Carradice D., Waterhouse P. M., Lieschke G. J. (2009). miR-451 regulates zebrafish erythroid maturation in vivo via its target gata2. Blood 113, 1794–1804 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena J. T., Sohn-Lee C., Rouhanifard S. H., Ludwig J., Hafner M., Mihailovic A., Lim C., Holoch D., Berninger P., Zavolan M. et al. (2009). miRNA in situ hybridization in formaldehyde and EDC-fixed tissues. Nat. Methods 6, 139–141 10.1038/nmeth.1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preis M., Gardner T. B., Gordon S. R., Pipas J. M., Mackenzie T. A., Klein E. E., Longnecker D. S., Gutmann E. J., Sempere L. F., Korc M. (2011). MicroRNA-10b expression correlates with response to neoadjuvant therapy and survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 5812–5821 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart B. J., Slack F. J., Basson M., Pasquinelli A. E., Bettinger J. C., Rougvie A. E., Horvitz H. R., Ruvkun G. (2000). The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 403, 901–906 10.1038/35002607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søe M. J., Møller T., Dufva M., Holmstrøm K. (2011). A sensitive alternative for microRNA in situ hybridizations using probes of 2′-O-methyl RNA + LNA. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 59, 661–672 10.1369/0022155411409411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienholds E., Kloosterman W. P., Miska E., Alvarez-Saavedra E., Berezikov E., de Bruijn E., Horvitz H. R., Kauppinen S., Plasterk R. H. (2005). MicroRNA expression in zebrafish embryonic development. Science 309, 310–311 10.1126/science.1114519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.