Summary

The primary cilium is a microtubule-based structure protruded from the basal body analogous to the centriole. CPAP (centrosomal P4.1-associated protein) has previously been reported to be a cell cycle-regulated protein that controls centriole length. Mutations in CPAP cause primary microcephaly (MCPH) in humans. Here, using a cell-based system that we established to monitor cilia formation in neuronal CAD (Cath.a-differentiated) cells and hippocampal neurons, we found that CPAP is required for cilia biogenesis. Overexpression of wild-type CPAP promoted cilia formation and induced longer cilia. In contrast, an exogenously expressed CPAP-377EE mutant that lacks tubulin-dimer binding significantly inhibited cilia formation and caused cilia shortening. Furthermore, depletion of CPAP inhibited ciliogenesis and such effect was effectively rescued by expression of wild-type CPAP, but not by the CPAP-377EE mutant. Taken together, our results suggest that CPAP is a positive regulator of ciliogenesis whose intrinsic tubulin-dimer binding activity is required for cilia formation in neuronal cells.

Keywords: Cilia biogenesis, Centriole, Ciliopathies, MCPH, Microcephaly, CENPJ

Introduction

The cilium is a microtubule-based structure, termed the axoneme, that protrudes from the basal body present in most, if not all, neurons in the mouse neocortex (Louvi and Grove, 2011). Recently, the distribution of neuronal cilia in the mouse neocortex have been extensively studied (Arellano et al., 2012), yet the molecular mechanisms underlying cilia formation and function in neuronal cells remain largely unknown. Defects in genes that are required for cilia assembly and functions lead to a wide range of human diseases called ciliopathies, including polycyctic kidney disease, retinal degeneration, and Bardet-Biedl syndrome (Gerdes et al., 2009; Nigg and Raff, 2009; Bettencourt-Dias et al., 2011; Louvi and Grove, 2011).

The centrosome is composed of mother and daughter centrioles surrounded by pericentriolar material (Nigg and Raff, 2009; Bettencourt-Dias et al., 2011). Centrioles are cylindrical, symmetrical structures with nine-fold triplet microtubules. The mother centriole has distal and subdistal appendages that are essential for membrane attachment and cilia formation. In human cells, procentrioles, or new centrioles, are initially formed through activation of PLK4 (Kleylein-Sohn et al., 2007) and CEP152 (Cizmecioglu et al., 2010; Dzhindzhev et al., 2010; Hatch et al., 2010), followed by recruitment of STIL and SAS6 to the proximal end of the parent centriole during G1/S phase (Tang et al., 2011). STIL/SAS6 may thus recruit CPAP to the base of the procentriole (Tang et al., 2011) on which CPAP assembles centriolar microtubules during S and G2 phase (Kohlmaier et al., 2009; Schmidt et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009). The daughter centriole then acquires appendages and matures to become the mother centriole in the subsequent cell cycle. When cells exit the cell cycle, the mother centriole can convert to a basal body and migrate to the cell membrane to assemble a cilium. Recently, two centrosomal proteins, Cep97 and CP110, were reported to act as suppressors of ciliogenesis (Spektor et al., 2007). Depletion of Cep97 and CP110 causes aberrant cilia formation, whereas overexpression of CP110 inhibits cilia biogenesis (Spektor et al., 2007). Interestingly, loss of Kif24, a member of the kinesin-13 subfamily that interacts with Cep97 and CP110, also induces the formation of primary cilia, implying that the centriolar kinesin Kif24 may remodel microtubules and regulate ciliogenesis (Kobayashi et al., 2011).

We previously identified the centrosomal protein, CPAP (centrosomal P4.1-associated protein), which is associated with the γ-tubulin complex (Hung et al., 2000). Further studies demonstrated that CPAP is a key regulator that controls centriole length (Schmidt et al., 2009; Kohlmaier et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009). Interestingly, recent studies showed that Dsas-4 (ortholog of CPAP) mutant flies have no cilia or flagella (Basto et al., 2006), implying that CPAP may participate in cilia formation in mammals. In this study, we establish a cell system to examine the roles of CPAP during ciliogenesis and show that CPAP may directly regulate cilia length and its intrinsic tubulin-dimer binding activity is required for cilia formation in neuronal cells.

Results

Establishment of a cell-based system for studying cilia formation in neuronal cells

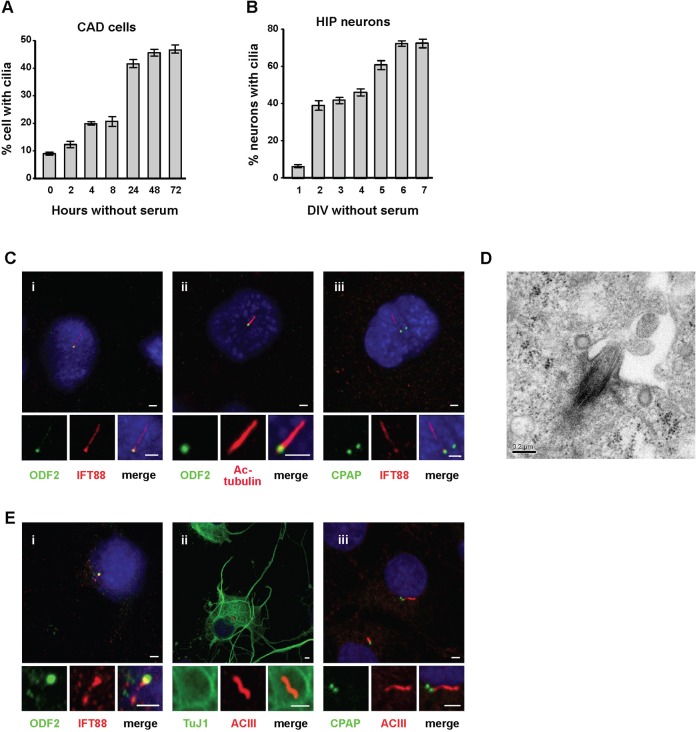

A previous study showed that cilia formation can be induced in the immortalized human retinal pigment epithelial cell line, hTERT-RPE1, by serum starvation (Pugacheva et al., 2007). To study ciliary biogenesis in neuronal cells, we used CAD (Cath.a-differentiated) cells, a central nervous system (CNS)-derived cell line (Qi et al., 1997; Li et al., 2007), and primary hippocampal neurons, as model systems. Seventy-two hours after seeding cells in Opti-MEM medium without serum, nearly 45% of CAD cells had visible cilia (Fig. 1A). Cilia were clearly stained with two cilia markers, IFT88 (intraflagellar transport protein 88) (Fig. 1Ci) and acetylated (Ac)-tubulin (Fig. 1Cii), and extended from an ODF2 (outer dense fiber protein 2)-positive basal body (Fig. 1Ci,ii). ODF2, which is specifically localized to distal/subdistal appendages of mother centrioles (Ishikawa et al., 2005), was used as a basal body marker. CPAP, previously reported to be localized to both mother and daughter centrioles (Tang et al., 2009), is commonly seen as two spots, but cilia protrude from only one of them (Fig. 1Ciii). Transmission electron microscopy of ciliated CAD cells revealed cilia protruding from the basal body (mother centriole), which attached to the plasma membrane through its appendages (Fig. 1D), indicating the formation of bona fide cilia was induced by serum starvation.

Fig. 1. Ciliary formation in CAD cells and primary hippocampal (HIP) neurons.

CAD cells (A) or hippocampal neurons (B) were cultured in serum-free medium, and ciliated cells were analyzed at the indicated times. DIV: days in vitro culture. Bar values are means ± s.d. of three experiments (n = 100 cells). (C) Images of CAD cells after 72 hours serum starvation, co-stained with DAPI and the indicated antibodies. (D) An electron microscopy image showing a cilium protruding from the basal body of a CAD cell. (E) Images of day 4 cultured (4 DIV) hippocampal neurons co-labeled with DAPI and the indicated antibodies. Bar in C,E: 2 µm. Bar in D: 0.2 µm.

Similar effects were also observed in primary neuronal cultures. Consistent with previous reports (Berbari et al., 2007; Arellano et al., 2012), hippocampal neurons cultured in serum-free conditions formed ciliated neurons that were positively labeled with TuJ1, a neuronal-specific class III β-tubulin, and ACIII (adenylyl cyclase III), a neuronal cilium marker (Fig. 1E). In this case, ACIII instead of Ac-tubulin was used as a cilium marker, because Ac-tubulin is not specific for neuronal cilia in hippocampal neuronal cultures (Berbari et al., 2007). Further analysis revealed that the IFT88-positive cilium was extended from the ODF2-labeled basal body (Fig. 1Ei), and CPAP marked both mother and daughter centrioles (Fig. 1Eiii). Quantitative analysis indicated a graduate increase of ciliated hippocampal neurons (positive for TuJ1 and ACIII) during 2–6 DIV (days in vitro) without serum (Fig. 1B). Collectively, these results indicate successful establishment of a cell system for monitoring cilia formation in neuronal CAD cells and hippocampal neurons.

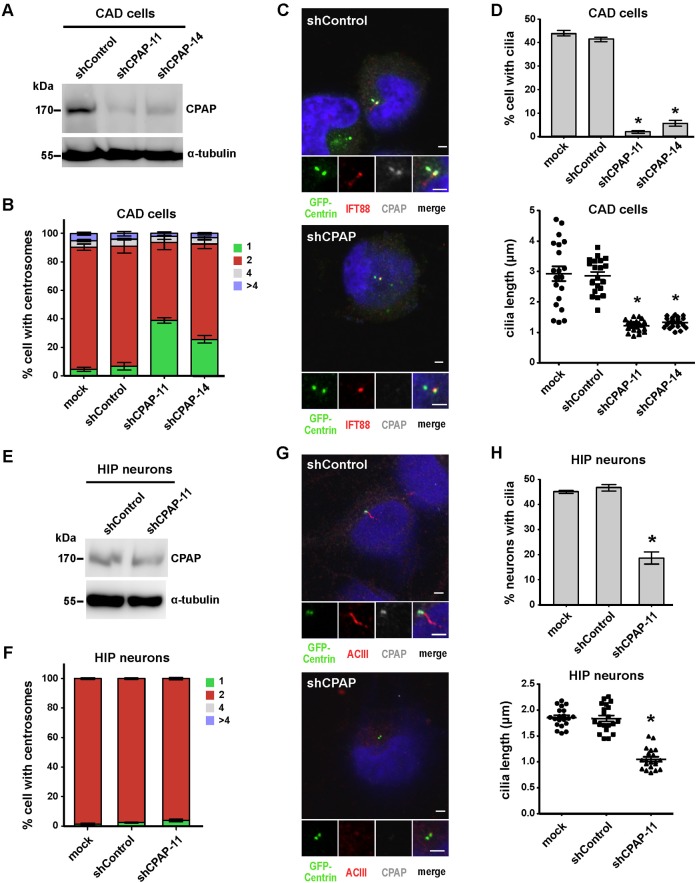

Depletion of CPAP inhibits cilia formation and causes cilia shortening

We and others previously reported that CPAP overexpression induces the growth of centrioles that extend from both mother and daughter centrioles (Kohlmaier et al., 2009; Schmidt et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009), and further showed that CPAP intrinsic tubulin-dimer binding activity is required for centriolar microtubule assembly during centriole elongation (Tang et al., 2009). Since the skeleton of cilia (axoneme) is a continuation and extension of microtubule doublets from the basal body structure, it is reasonable to speculate that CPAP might be involved in cilia formation. To test this hypothesis, we depleted CPAP by simultaneously transfecting CAD cells with an improved silencing construct (shCPAP-11 or shCPAP-14) that co-expresses GFP-centrin (a GFP-fused centriole marker) and small hairpin RNA (shRNA) specific for CPAP, and then serum starved cells for 72 hours. Both shCPAP-11 and shCPAP-14 showed specific inhibition of CPAP expression, as evidenced by immunoblotting (Fig. 2A) and immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 2C). Centrioles were identified based on GFP-centrin signals and cilia were defined by IFT88 staining. Our results showed that CPAP depletion significantly inhibited normal centrosome duplication in cycling CAD cells (Fig. 2B), consistent with previous reports (Kohlmaier et al., 2009; Schmidt et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009). However, CPAP knockdown did not appear to affect centrosome numbers in non-cycling hippocampal neurons (Fig. 2F). Interestingly, depletion of CPAP not only blocked cilia formation, it also caused cilia shortening. The formation of cilia was significantly reduced in CAD cells treated with shCPAP-11 (2%) or shCPAP-14 (5.7%) compared to mock (44%)- or shControl (41.3%)-transfected cells (Fig. 2D, upper panel). In addition, we frequently observed shorter cilia in CPAP-depleted cells (∼2.9 µm in mock and shControl vs. ∼1.2 µm in shCPAP-11 and shCPAP-14) (Fig. 2D, lower panel). Similar but less efficient effects were also found in shCPAP-treated hippocampal neurons (Fig. 2E,H). Taken together, our results support the notion that CPAP is required for cilia biogenesis and may participate in regulating cilia length in neuronal cells.

Fig. 2. Depletion of CPAP suppresses cilia formation.

CAD cells (A-D) and hippocampal neurons (E-H) were transfected with shControl or shCPAP (-11 and -14) constructs and then serum starved for 72 hours (CAD cells) or 4 DIV (hippocampal neurons). Western blot analysis of shCPAP knockdown in CAD cells (A) and hippocampal neurons (E); α-tubulin was used as a loading control. Quantitative analysis of centrosome numbers in CAD cells (B) and hippocampal neurons (F) treated with shCPAP. Immunofluorescence images of shControl- and shCPAP-11-treated CAD cells (C) and hippocampal neurons (G) labeled with DAPI and the indicated antibodies. Quantitative analysis of ciliated cell numbers and cilia length in CAD cells (D) and hippocampal neurons (H). Bar values are means ± s.d. of three experiments (n = 100 counted for ciliated cells; n = 20 counted for cilia length). *p<0.05 vs. the respective control (Student's t-test). Due to the expression of exogenous shRNA is gradually reduced in hippocampal neurons after long-term culture (> 5 DIV), we selected 4 DIV as the time point for analysis. Bar in C,G: 2 µm.

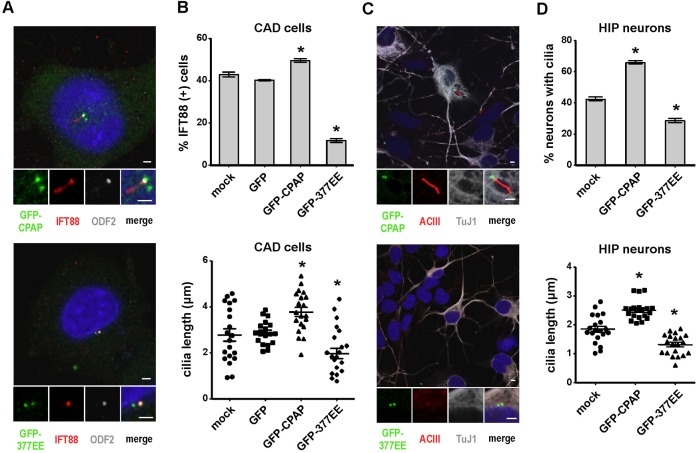

Overexpression of CPAP but not CPAP-377EE mutant promotes cilia formation and induces longer cilia

We next investigated the potential roles of CPAP during cilia biogenesis by overexpressing wild-type GFP-CPAP or a GFP-CPAP-377EE mutant into CAD cells (Fig. 3A,B) and hippocampal neurons (Fig. 3C,D), followed by serum starvation. Our results showed that excess GFP-CPAP promoted the formation of IFT88-labeled cilia (Fig. 3A,B) in CAD cells. In contrast, overexpression of GFP-CPAP-377EE, with a deficiency in tubulin-dimer binding activity (Hsu et al., 2008), significantly inhibited cilia formation (Fig. 3A,B). Similar effects were also observed in hippocampal neurons (Fig. 3C,D). Furthermore, excess GFP-CPAP induced the formation of longer cilia (3.78 µm in GFP-CPAP vs. 2.89 µm in GFP control) (Fig. 3B, lower panel), whereas GFP-CPAP-377EE produced much shorter cilia (1.98. µm in GFP-CPAP-377EE vs. 2.89 µm in GFP control) (Fig. 3B, lower panel). Consistent with CPAP depletion studies (Fig. 2), our overexpression results suggest that CPAP may act as a positive regulator of cilia length whose intrinsic tubulin-dimer binding activity is essential for cilia formation.

Fig. 3. Overexpression of wild-type GFP-CPAP, but not GFP-CPAP-377EE (GFP-377EE), induces cilia formation and promotes the growth of cilia.

CAD cells (A,B) and hippocampal neurons (C,D) were transfected with GFP-CPAP, GFP-377EE, or GFP vector alone (control) and then serum starved for 72 hours (CAD cells) or 4 DIV (hippocampal neurons). Images of CAD cells (A) and hippocampal neurons (C) labeled with DAPI and the indicated antibodies. GFP-CPAP and GFP-377EE were directly visualized by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Quantitative analysis of ciliated cell numbers and cilia length in CAD cells (B) and hippocampal neurons (D). Bar values are means ± s.d. of three experiments (n = 100 counted for ciliated cells; n = 20 counted for cilia length). *p < 0.05. Bar in A,C: 2 µm.

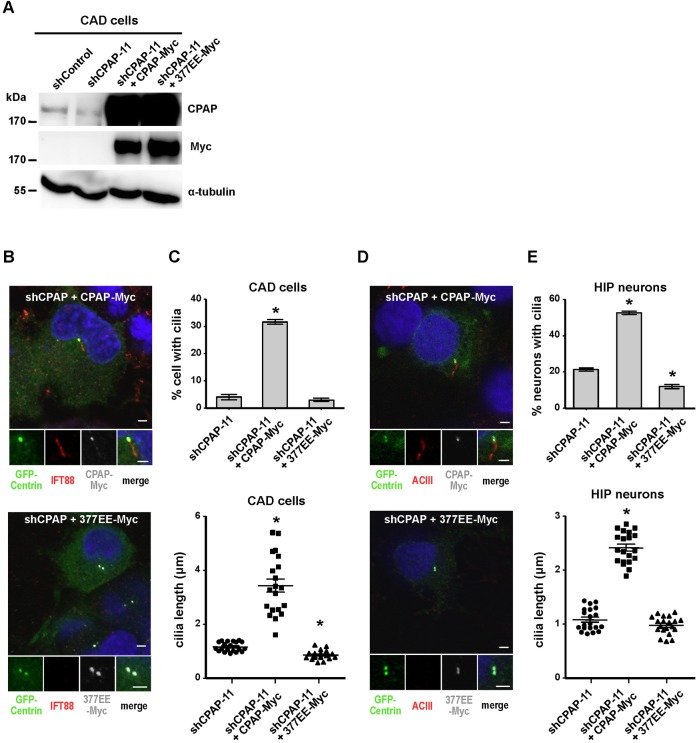

Inhibition of cilia formation by CPAP depletion is rescued by exogenously expressed wild-type CPAP, but not by the CPAP-377EE mutant

Our results showed that CPAP depletion suppresses the assembly of primary cilia and reduces their length (Fig. 2D). To further investigate whether this repression can be rescued by exogenously expressed CPAP, we co-transfected CAD cells with shCPAP-11 and either CPAP-Myc or CPAP-377EE-Myc, followed by serum starvation. As shown in Fig. 4B, shCPAP-mediated inhibition of cilia formation was effectively rescued by overexpression of CPAP-Myc, but not by overexpression of the CPAP-377EE-Myc mutant. The ciliated cell population was significantly increased (to 31.7%) in CPAP-Myc transfected cells compared to that in shCPAP-11 controls (4.0%) (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, cilia length was dramatically increased in cells transfected with wild-type CPAP-Myc (3.44 µm) compared to shCPAP-11 controls (1.17 µm) (Fig. 4C). In contrast, no such effects were observed in CPAP-377EE-Myc-transfected cells (Fig. 4C), implying that the intrinsic tubulin-dimer binding activity of CPAP is required for cilia formation. Similar effects were also found in hippocampal neurons (Fig. 4D,E).

Fig. 4. Exogenous expression of CPAP-Myc effectively rescues ciliagenesis failure induced by CPAP depletion.

shCPAP-11 was co-transfected with wild-type CPAP-Myc or CPAP-377EE-Myc (377EE-Myc) into CAD cells (A-C) and hippocampal neurons (D,E) followed by serum starvation. (A) Western blot analysis of shCPAP-11 knockdown and CPAP rescue in CAD cells. Images of CAD cells (B) and hippocampal neurons (D) co-stained with DAPI and the indicated antibodies. CPAP-Myc and CPAP-377EE-Myc were detected with an anti-Myc antibody. Quantitative analysis of ciliated cell numbers and cilia length in CAD cells (C) and hippocampal neurons (E). Bar values are means ± s.d. of three experiments (n = 100 counted for ciliated cells; n = 20 counted for cilia length). *p < 0.05. Bar in B,D: 2 µm.

Discussion

In this study, we have set up a cell-based system to examine the role of CPAP during cilia biogenesis in neuronal cells. We found that CPAP is localized at the base of cilia (basal body) (Fig. 1Ciii,Eiii). Overexpression of CPAP promoted cilia formation (Fig. 3B,D, upper panel) and depletion of CPAP by shRNA treatment suppressed cilia assembly (Fig. 2D,H, upper panel) in neuronal cells. Our findings are consistent with the role of DSas-4 (an ortholog of CPAP) during cilia biogenesis in D. Melanogaster (Basto et al., 2006). Surprisingly, we also noticed that CPAP may directly affect cilia length in neuronal cells. This concept was supported by three independent lines of evidence including excess CPAP induced longer cilia (Fig. 3B,D, lower panel), while depletion of CPAP (Fig. 2D,H, lower panel) or overexpression of CPAP-377EE mutant (Fig. 3B,D, lower panel) produced much shorter cilia. Together, our results imply that CPAP acts as a positive regulator in cilia biogenesis and its intrinsic tubulin-dimer binding activity is required for ciliary microtubule assembly during cilia biogenesis.

Recently, it has been reported that DSas-4 mutant flies have no cilia or flagella and die shortly after birth because they lack cilia in their sensory neurons (Basto et al., 2006). These mutant flies also have partially asymmetric division defects in their neuroblasts. Interestingly, mutations in the CPAP/CENPJ (MCPH6) gene cause primary microcephaly (MCPH) in humans (Bond et al., 2005), which has been attributed to defects in asymmetric cell division during early fetal brain development (Cox et al., 2006). To study the role of CPAP in ciliogenesis and asymmetric cell division, we have established a conditional Cpap-knockout mouse model. Unexpectedly, our preliminary studies revealed that constitutive homozygous Cpap knockout (Cpap−/−) is embryonic lethal at about E8.5, implying that Cpap is essential during early embryonic development (unpublished data). Future analyses of neuron-specific conditional Cpap-knockout mice may resolve how CPAP functions in mammalian neuronal cells.

Materials and Methods

DNA constructs and cell transfection

Human GFP-CPAP, GFP-CPAP-377EE, CPAP-Myc, and CPAP-377EE-Myc DNA constructs were prepared as described previously (Tang et al., 2009). pGShin2-centrin was constructed by inserting a full-length centrin cDNA downstream of the GFP sequence in the pGShin2 vector (Kojima et al., 2004). Two silencing constructs, shCPAP-11 (5′-AGATAGAGATGCTCGTCAA-3′) and shCPAP-14 (5′-GGAAGCAGATGATAAGCAA-3′) that co-express GFP-centrin and a shRNA specific for mouse CPAP were cloned into the pGShin2 vector.

CAD cells were kindly provided by Val J. Watts (Purdue University). Primary hippocampal neurons were cultured as described previously (Kaech and Banker, 2006). CAD cells were transiently transfected with various cDNA constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as described previously (Tang et al., 2009). For serum starvation experiments, the medium was changed to Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) and cells were cultured for the indicated times after transfection. For shRNA experiments, CAD cells were transfected with pGShin2-Centrin (shControl), shCPAP-11, or shCPAP-14 using Lipofectamine 2000, and then incubated for 72 hours. Primary hippocampal neurons were transfected with various constructs using an Amaxa neuron nucleofector Kit (Lonza, Basel, BS, Switzerland), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Antibodies and immunofluorescence confocal microscopy

The antibodies used were anti-CPAP (Tang et al., 2009), anti-γ-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), anti-TuJ1 (Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA), anti-ODF2 (Abcam, Cambridge Science Park, Cambridge, UK), anti-ACIII (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-IFT88 (Abcam), anti-acetylated tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-Myc (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY, USA).

For immunofluorescence analysis, CAD cells or hippocampal neurons grown on coverslips were fixed in methanol for 10 minutes at −20°C as described previously (Tang et al., 2009). After blocking with 10% BSA for 1 hour, fixed cells were incubated with the indicated primary antibodies. After washing, cells were incubated with appropriate Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). DNA was counterstained with DAPI (4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). The samples were observed using an LSM 700 confocal system (Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Electron microscopy

CAD cells were grown on a plastic film in 35 mm dishes and serum starved for 72 hours. Cells were prefixed in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 1 hour at 4°C. After washing, cells were postfixed in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer containing 1% OsO4 for an additional 1 hour at 4°C. After washing, cells were incubated in 1% uranyl acetate for 1 hour at 4°C, then dehydrated in serial ethanol and embedded in Spur resin. Ultrathin sections (80 nm) were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The samples were examined with a Tecnai G2 Spirit Twin electron microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA).

Acknowledgments

We thank Sue-Ping Lee and Sue-Ping Tsai for their technical assistance with electron microscopy. We thank Yi-Nan Lin for constructing pGShin2-centrin, and Yi-Shuian Huang for helping with hippocampal neuron culture. pGShin2 was kindly provided by Dr S.-I. Kojima (Gakushuin University). W.K.-S. was supported by student fellowships from NSC (NSC100-2311-B001-012).

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

References

- Arellano J. I., Guadiana S. M., Breunig J. J., Rakic P., Sarkisian M. R. (2012). Development and distribution of neuronal cilia in mouse neocortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 520, 848–873 10.1002/cne.22793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basto R., Lau J., Vinogradova T., Gardiol A., Woods C. G., Khodjakov A., Raff J. W. (2006). Flies without centrioles. Cell 125, 1375–1386 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berbari N. F., Bishop G. A., Askwith C. C., Lewis J. S., Mykytyn K. (2007). Hippocampal neurons possess primary cilia in culture. J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 1095–1100 10.1002/jnr.21209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt-Dias M., Hildebrandt F., Pellman D., Woods G., Godinho S. A. (2011). Centrosomes and cilia in human disease. Trends Genet. 27, 307–315 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond J., Roberts E., Springell K., Lizarraga S. B., Scott S., Higgins J., Hampshire D. J., Morrison E. E., Leal G. F., Silva E. O. et al. (2005). A centrosomal mechanism involving CDK5RAP2 and CENPJ controls brain size. Nat. Genet. 37, 353–355 10.1038/ng1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cizmecioglu O., Arnold M., Bahtz R., Settele F., Ehret L., Haselmann-Weiss U., Antony C., Hoffmann I. (2010). Cep152 acts as a scaffold for recruitment of Plk4 and CPAP to the centrosome. J. Cell Biol. 191, 731–739 10.1083/jcb.201007107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J., Jackson A. P., Bond J., Woods C. G. (2006). What primary microcephaly can tell us about brain growth. Trends Mol. Med. 12, 358–366 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhindzhev N. S., Yu Q. D., Weiskopf K., Tzolovsky G., Cunha-Ferreira I., Riparbelli M., Rodrigues-Martins A., Bettencourt-Dias M., Callaini G., Glover D. M. (2010). Asterless is a scaffold for the onset of centriole assembly. Nature 467, 714–718 10.1038/nature09445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes J. M., Davis E. E., Katsanis N. (2009). The vertebrate primary cilium in development, homeostasis, and disease. Cell 137, 32–45 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch E. M., Kulukian A., Holland A. J., Cleveland D. W., Stearns T. (2010). Cep152 interacts with Plk4 and is required for centriole duplication. J. Cell Biol. 191, 721–729 10.1083/jcb.201006049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu W.-B., Hung L.-Y., Tang C.-J. C., Su C.-L., Chang Y., Tang T. K. (2008). Functional characterization of the microtubule-binding and -destabilizing domains of CPAP and d-SAS-4. Exp. Cell Res. 314, 2591–2602 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung L. Y., Tang C. J., Tang T. K. (2000). Protein 4.1 R-135 interacts with a novel centrosomal protein (CPAP) which is associated with the gamma-tubulin complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 7813–7825 10.1128/MCB.20.20.7813--7825.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H., Kubo A., Tsukita S., Tsukita S. (2005). Odf2-deficient mother centrioles lack distal/subdistal appendages and the ability to generate primary cilia. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 517–524 10.1038/ncb1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaech S., Banker G. (2006). Culturing hippocampal neurons. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2406–2415 10.1038/nprot.2006.356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleylein-Sohn J., Westendorf J., Le Clech M., Habedanck R., Stierhof Y.-D., Nigg E. A. (2007). Plk4-induced centriole biogenesis in human cells. Dev. Cell 13, 190–202 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Tsang W. Y., Li J., Lane W., Dynlacht B. D. (2011). Centriolar kinesin Kif24 interacts with CP110 to remodel microtubules and regulate ciliogenesis. Cell 145, 914–925 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmaier G., Lončarek J., Meng X., McEwen B. F., Mogensen M. M., Spektor A., Dynlacht B. D., Khodjakov A., Gönczy P. (2009). Overly long centrioles and defective cell division upon excess of the SAS-4-related protein CPAP. Curr. Biol. 19, 1012–1018 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima S.-I., Vignjevic D., Borisy G. G. (2004). Improved silencing vector co-expressing GFP and small hairpin RNA. Biotechniques 36, 74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Hou L. X.-E., Aktiv A., Dahlström A. (2007). Studies of the central nervous system-derived CAD cell line, a suitable model for intraneuronal transport studies? J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 2601–2609 10.1002/jnr.21216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvi A., Grove E. A. (2011). Cilia in the CNS: the quiet organelle claims center stage. Neuron 69, 1046–1060 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg E. A., Raff J. W. (2009). Centrioles, centrosomes, and cilia in health and disease. Cell 139, 663–678 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugacheva E. N., Jablonski S. A., Hartman T. R., Henske E. P., Golemis E. A. (2007). HEF1-dependent Aurora A activation induces disassembly of the primary cilium. Cell 129, 1351–1363 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y., Wang J. K., McMillian M., Chikaraishi D. M. (1997). Characterization of a CNS cell line, CAD, in which morphological differentiation is initiated by serum deprivation. J. Neurosci. 17, 1217–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T. I., Kleylein-Sohn J., Westendorf J., Le Clech M., Lavoie S. B., Stierhof Y.-D., Nigg E. A. (2009). Control of centriole length by CPAP and CP110. Curr. Biol. 19, 1005–1011 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spektor A., Tsang W. Y., Khoo D., Dynlacht B. D. (2007). Cep97 and CP110 suppress a cilia assembly program. Cell 130, 678–690 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.-J. C., Fu R.-H., Wu K.-S., Hsu W.-B., Tang T. K. (2009). CPAP is a cell-cycle regulated protein that controls centriole length. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 825–831 10.1038/ncb1889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.-J. C., Lin S.-Y., Hsu W.-B., Lin Y.-N., Wu C.-T., Lin Y.-C., Chang C.-W., Wu K.-S., Tang T. K. (2011). The human microcephaly protein STIL interacts with CPAP and is required for procentriole formation. EMBO J. 30, 4790–4804 10.1038/emboj.2011.378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]