Summary

Seahorses are the vertebrate group with the embryonic development occurring within a special pouch in males. To understand the reproductive efficiency of the lined seahorse, Hippocampus erectus Perry, 1810 under controlled breeding experiments, we investigated the dynamics of reproductive rate, offspring survivorship and growth over births by the same male seahorses. The mean brood size of the 1-year old pairs in the 1st birth was 85.4±56.9 per brood, which was significantly smaller than that in the 6th birth (465.9±136.4 per brood) (P<0.001). The offspring survivorship and growth rate increased with the births. The fecundity was positively correlated with the length of brood pouches of males and trunk of females. The fecundity of 1-year old male and 2-year old female pairs was significantly higher than that from 1-year old couples (P<0.001). The brood size (552.7±150.4) of the males who mated with females that were isolated for the gamete-preparation, was larger than those (467.8±141.2) from the long-term pairs (P<0.05). Moreover, the offspring from the isolated females had higher survival and growth rates. Our results showed that the potential reproductive rate of seahorses H. erectus increased with the brood pouch development.

Keywords: Fecundity, Reproductive efficiency, Seahorses, Hippocampus erectus

Introduction

In most animals, the potential reproductive rate is the population's mean offspring production when not constrained by the availability of mates (Clutton-Brock and Vincent, 1991; Clutton-Brock and Parker, 1992; Parker and Simmons, 1996; Wilson et al., 2003), and the reproductive rate often vary because of mating competition and parental investment (Trivers, 1972). In some syngnathid species, the reproduction is influenced by the complex brooding structure, brood pouch development, sexual selection, mating patterns and social promiscuity (Parker and Simmons, 1996; Carcupino et al., 2002; Wilson et al., 2003; Vincent et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2006; Naud et al., 2009).

The family Syngnathidae (seahorses and pipefishes) is the sole vertebrate group where the embryonic development occurs within a special pouch in males (Herald, 1959) that provides aeration, protection, osmoregulation and nutrition to the embryo or offspring after the females depositing eggs during mating (Linton and Soloff, 1964; Berglund et al., 1986; Partridge et al., 2007; Ripley, 2009). This pouch is similar to the placental function in mammals and acts like the mammalian uterus, and the embryos become embedded within depressions of the interior lining of the brood pouch (Carcupino et al., 1997; Foster and Vincent, 2004).

For syngnathid species, the survivorship of offspring is often used to evaluate the reproductive ability of the parents (Wootton, 1990; Cole and Sadovy, 1995; Vincent and Giles, 2003). The offspring survivorship of pipefish within a pregnancy is affected by the size of the female, the number of eggs transferred and the male's sexual responsiveness (Paczolt and Jones, 2010). Dzyuba et al. (Dzyuba et al., 2006) reported that in the seahorse Hippocampus kuda the parental size and age could affect the number, survivorship and even the growth of the offspring. Not all the eggs deposited in the male's pouch successfully complete the development and hatch as juveniles (offspring). For example, 1.23% of the eggs failed to develop in the pouch of wild H. abdominalis (Foster and Vincent, 2004); 2–33% of the eggs were found to be sterile in H. erectus pouches (Teixeira and Musick, 2001); and 45% of the eggs were lost during the pregnancy of H. fuscus (Vincent, 1994a). Moreover, the gonad development, clutch size and even the mate competition and physical interference during courtship and egg transfer should also be considered when estimating the offspring number from parents (Vincent and Giles, 2003; Foster and Vincent, 2004; Lin et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2007; Paczolt and Jones, 2010).

Many studies on understanding the potential reproductive rate in seahorses have been conducted through estimating the operational sex ratios, courtship roles, parental investment patterns, mate competitions and so on (A. C. J. Vincent, Reproductive Ecology of Seahorses, PhD thesis, Cambridge University, UK, 1990) (Vincent, 1994a; Vincent, 1994b; Masonjones, 1997; Masonjones and Lewis, 2000). For the investigation of mortality and growth of offspring, most reports focus on the controlled culture experiments, such as effects of environmental factors, diets and culture protocols on the survivorship in a limited duration (Scarratt, 1996; Job et al., 2002; Woods, 2000; Woods, 2003; Hilomen-Garcia et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2008; Koldewey and Martin-Smith, 2010).

The seahorse has a special reproductive strategy, but no report has been made on the dynamics of reproductive rate, especially in the first few births. The lined seahorse, H. erectus Perry, 1810 is mainly found from Nova Scotia along the western Atlantic coast, through the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean to Venezuela, in shallow inshore areas to depths of over 70 m (Scarratt, 1996; Lourie et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2008). The purpose of the present study was to investigate the dynamics of the reproductive rate over the first few births, and then evaluate the effects of parent ages and mating limitation on the reproductive rate, offspring survivorship and growth of H. erectus.

Materials and Methods

Experimental seahorses

The lined seahorses H. erectus used in this study were cultured in Leizhou Seahorse Center of South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (SCSIO-CAS) (latitude 110.04°E, longitude 20.54°N) with Animal Ethics approval for experimentation granted by the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The F2 generation of this species was used for all the controlled breeding experiments. After being released from the broodstock male (F1), the offspring (F2) were cultured in separate concrete outdoor ponds (5×4×1.4 m), with recirculating sea water treated with double sand filtration. Seahorses were fed daily with rotifers, copepods, Artemia, Mysis spp. and Acetes spp. A black nylon mesh was used to shade the outdoor ponds to keep the light intensity below 3400 Lux. The temperature was 22–28°C and salinity was 31–34‰ during the study from March 2009 to March 2011.

Reproductive rate over successive birth

Sex was determined by the presence or absence of brood pouch at approximately 70 days after birth. Seventy-five pairs of male (standard body length: 10.3±0.6 cm) and female (standard body length: 8.7±0.8 cm) F2 seahorses were haphazardly selected from the outdoor ponds and cultured in 5 indoor round tanks (diameter 1.6 m, depth 0.9 m) with the stocking density of 15 pairs per tank (1 seahorse/60L). In order to estimate the reproductive rate over successive birth, the broods (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th successive births) from the same pair were recorded. The seahorse pair that mated and then successfully hatched the offspring were marked by the nylon ring with number around their necks. Plastic plants and corallites were used as the substrate and holdfasts for the fish. The indoor husbandry protocol was the same as that in the outdoor ponds, and the light intensity was adjusted through the glass ceiling and black nylon mesh.

Fourteen, 13, 12, 11, 9 and 9 batches of juveniles from 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th successive births respectively were used to estimate the survivorship and growth of offspring. 60 juveniles haphazardly selected from each brood (batch) were cultured in 3 recirculating tanks (L×W×H, 50×30×40 cm) (each with 20 juveniles) for 5 weeks. The juveniles were not fed during the first 10 hours after birth, and then they were fed with copepods and newly hatched Artemia nauplii in excess. The temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen (DO), light intensity and photoperiod in the tanks were 26±1.0°C, 32±1.0‰, 6.5±0.5 mg/L and 2000 Lux, and 16 L (0700–2300 h): 8 D (2300–0700 h), respectively. The tanks were aerated gently so as not to form excessive air bubbles and cause turbulence.

In order to assess if the brood size was related to the body condition factor of parent seahorses, the brood pouch length (parallel length from the anus to the tip of the brood pouch on the tail) of the male seahorse and trunk length of the female of each brooding pair were measured after the copulation. Then the linear regressions for the relationship among offspring number, brood pouch size of males and trunk length of females were analyzed.

Effect of parent ages

To compare the reproductive rate of young (one year old) (M1, F1, never mated) and old (two years old) seahorse pairs (M2, F2, mated many times), 4 combination treatments (M1: F1, M2: F1, M1: F2 and M2: F2, respectively) were set up, each with 4 replicates and each replicate had 15 pairs. The body lengths of the male and female seahorses were 17.4±1.6 and 15.8±2.1 cm, respectively. Among the 60 pairs of parent seahorses in each treatment, 7 broods from 7 of the males were haphazardly selected and 100 juveniles in each brood were cultured for 5 weeks following the same culture protocol as in the last experiment.

Effect of mating limitation (female isolation)

In order to investigate the effect of mating limitation (female isolation) on reproductive rate of H. erectus, the control and experimental groups of 2-year old seahorse pairs (males: 16.6±2.1 cm, females: 15.8±1.7 cm) were used. In the control (TR-1), 60 pairs of seahorses haphazardly selected from the concrete outdoor ponds were cultured in 4 indoor tanks (diameter 1.6 m, depth 0.9 m) as 4 replicates, and each tank had 15 pairs with the stocking density of 1 seahorse/60L. During the experiment, four successive births (TR-1-1, TR-1-2, TR-1-3 and TR-1-4, and 10, 10, 9 and 8 males released their offspring in each birth, respectively) from the same pair of seahorses were utilized.

In the experimental treatment (TR-2), 60 pairs of 2-year old seahorses derived from the same brood stock as the seahorses in control group were also cultured in 4 round tanks (diameter 1.6 m, depth 0.9 m) as 4 replicates, and each had 15 pairs of seahorses. In a tank, the male and female seahorses were cultured separately (male groups and female groups) through a glass wall in the seawater. When the gonads of female seahorse matured (the abdomen was bosomy and the cloaca was protuberant), the female was transferred over to the male side. After the courtship and mating, the female was put back to the female side. The pregnant male seahorse released his babies at approximately 20 days later, depending on the water temperature and nutritional conditions. The female seahorse (gonad already matured) was returned to the male side of the tank where she paired and mated again (not necessarily with the original partners) six days after the male released his offspring (a modified method from Masonjones' and Lewis' investigation (Masonjones and Lewis, 2000)). Brood sizes from the four consecutive births (TR-2-1, TR-2-2, TR-2-3 and TR-2-4, and 11, 9, 9 and 8 males released their offspring in each birth, respectively) were counted. The juveniles from both the control and the treatment groups were cultured for 5 weeks and the mean survival rate and the distributions for standard body length of juveniles per brood were recorded.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the software SPSS 17 (Statistical Program for Social Sciences 17) and Sigma PLOT 10.0. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), regression analysis and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test were used to assess the relationship among the brood size, survival rate and body size of the juveniles among the treatments. All the variables were tested for normality and homogeneity. If ANOVA effects were significant, comparisons between the different means were made using post hoc least significant differences (LSD).

Results

Dynamics of reproductive rate

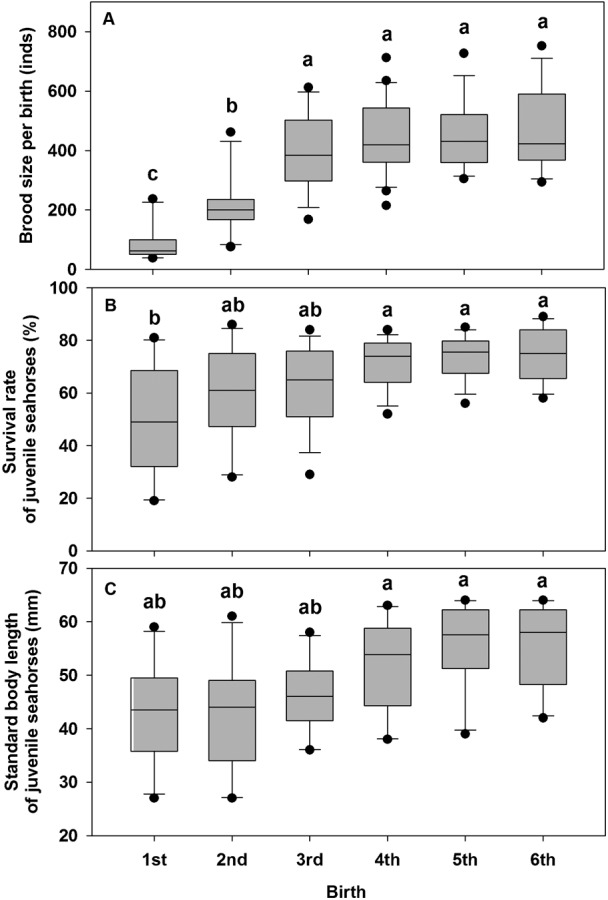

Among the 75 pairs of parent seahorses, 85 broods (batches) were concerned by 10 male seahorses at 6 successive births (1st (n = 21, 21 males released their offspring in the 1st birth), 2nd (n = 16), 3rd (n = 15), 4th (n = 12), 5th (n = 11) and 6th (n = 10), respectively) and only 10 pairs of seahorses were monogamist. Brood size (fecundity) in the first 2 births was significantly lower than those in the following 4 (n = 85, F5, 79 = 21.28, P<0.001), and varied widely among the broods in the same birth (e.g. 46 to 237 per brood in the 1st birth, 294 to 752 per brood in the 6th birth) (Fig. 1A). The brood size increased significantly during the first 3 births (Fig. 1A). The brood size (mean±S.D.) in the 6 successive births was 85.4±56.9, 216.7±101.8, 400.1±127.5, 451.2±123.8, 458.3±117.6 and 465.9±136.4, respectively, and can be expressed by the formula: y = 232.25Ln(x) + 91.526 (r2 = 0.9412, F5, 79 = 21.28, P<0.001, n = 85).

Fig. 1. Brood size, offspring survivorship and growth of young pair parent seahorses Hippocampus erectus at first 6 successive births.

1st (n = 21 broods), 2nd (n = 16), 3rd (n = 15), 4th (n = 12), 5th (n = 11) and 6th (n = 10), respectively. Different superscripts indicate the significant difference among the treatments (P<0.05).

High mortality of the juveniles occurred in the first 3 births (n = 68, F5, 62 = 4.97, P<0.001) (Fig. 1B). Body sizes (mean standard body length) in the first 3 births were approximately 25% lower than those in the last 3 births after 5 weeks (n = 68, F5, 62 = 5.25, P<0.001) (Fig. 1C).

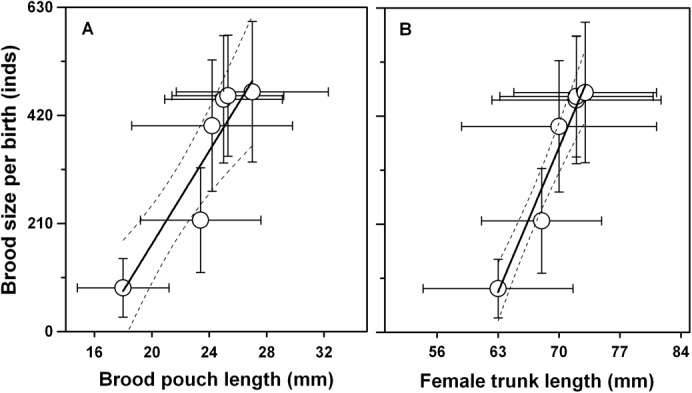

The correlation between brood pouch length and brood size was positively significant (F1, 4 = 22.99, P = 0.0087, r2 = 0.9229) (Fig. 2A), and the brood size was also significantly correlated with the trunk length of females (F1, 4 = 78.08, P = 0.0009, r2 = 0.9753) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. The relationships between brood size and brood pouch length.

Scatter-plots and linear regression lines for the relationships between brood size and brood pouch length of male seahorses Hippocampus erectus (95% confidence bands); between brood size and the trunk length of females (95% confidence bands) for the first 6 successive births.

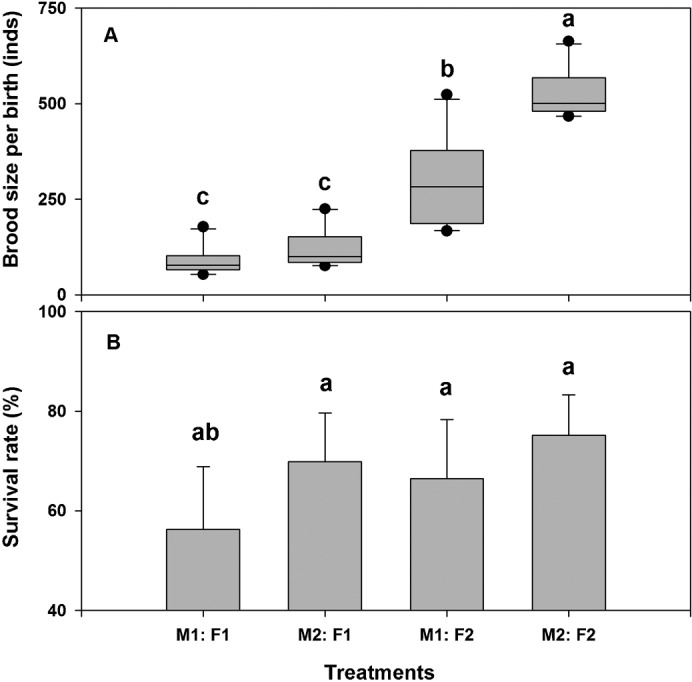

Effect of parent age

Brood size from the 1-year old females (M1: F1, M2: F1) (89.6±36.9 and 122.2±49.5, respectively) was significantly smaller than those from the 2-year old pairs (526.8±63.9) (n = 40, F3, 36 = 152.42, P = 0.000). The pairs of 1-year old males and 2-year old females produced intermediate number of offspring (302.4±113.8 per brood), which was significantly higher than that in groups of M1: F1 and M2: F1 (n = 30, F2, 27 = 29.33, P = 0.000) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. Brood size and offspring survivorship under different ages.

Brood size and offspring survivorship under different ages (M1: F1, M2: F1, M1: F2 and M2: F2) of pair parent seahorses Hippocampus erectus. Different superscripts indicate the significant difference among the treatments (P<0.05). M1, 1-year old male seahorse; F1, 1-year old female seahorse; M2, two years old male seahorse; F2, two years old female seahorse.

After 5 weeks, the juvenile seahorses had different survivorship among the 4 treatments (n = 28, F2, 24 = 5.53, P = 0.005), with the juveniles from 2-year old parents had the highest survival rate of 75.1±8.2%. The offspring from the 2-year old male and 1-year old female pairs (M2: F1, 69.8±12.8%) also had a higher survival rate than those from 1-year old males (n = 28, F2, 18 = 1.902, P = 0.178) (Fig. 3B).

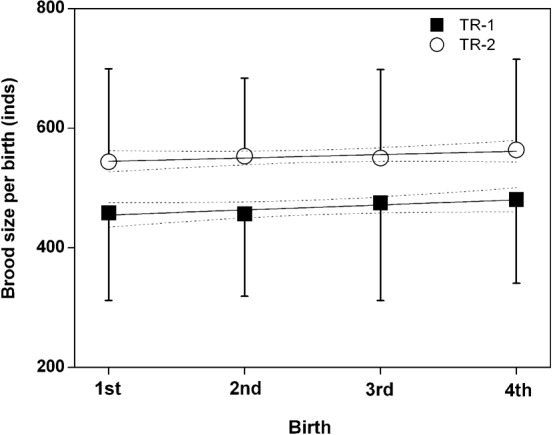

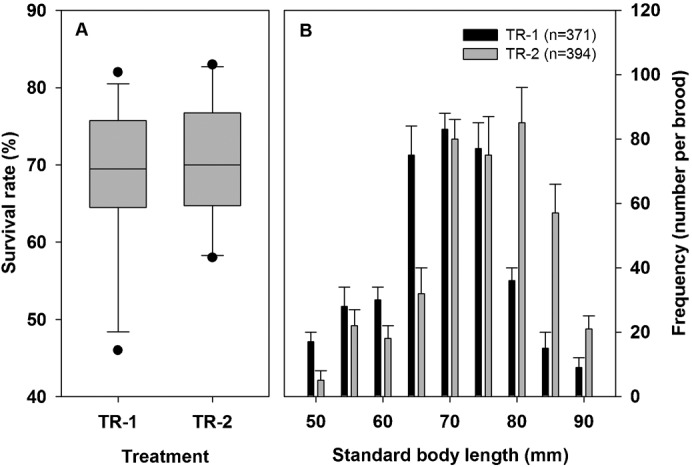

Effect of mating limitation

Brood sizes from the 4 TR-1 treatment were not significantly different from those of the 4 TR-2 treatment (mating limitation by females) (ANOVA-Tukey HSD analysis: n = 74, F7, 66 = 0.89, P = 0.513). However, when treated as two groups, the mean brood size of TR-1 was 467.8±141.2 per brood, which was approximately 18% lower than those in TR-2 (552.7±150.4 per brood) (n = 74, F1, 72 = 6.56, P = 0.013) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Brood size of four successive births by male seahorses Hippocampus erectus in the two groups (TR-1, TR-2).

In TR-1 groups: male and female seahorses were cultured together (broods per birth: n = 10, 10, 9 and 8); in TR-2 groups: females were isolated (n = 11, 9, 9 and 8) (ANOVA-Tukey HSD analysis: n = 74, F7, 66 = 0.89, P = 0.513; 95% confidence bands).

The mean survival rate of the juveniles after five weeks of culture in TR-1 and TR-2 was not significantly different (68.1±10.0 and 70.2±7.9%, respectively) (n = 74, F1, 72 = 0.27, P = 0.610) (Fig. 5A). The mean standard body length of the juveniles in TR-1 and TR-2 were 69.2±21.5 and 74.4±18.7 mm (K-S test: n = 74, F1, 72 = 2.17, P<0.05). The mean frequency distributions of standard body length of the juveniles in the two groups were shown in Fig. 5B. Most juveniles in TR-2 distributed between 70 to 85 mm in standard body length, and in TR-1, the juveniles' body length ranged from 65 to 75 mm.

Fig. 5. Survivorship and frequency distribution.

Survivorship and frequency distribution by standard body length growth comparison of juvenile seahorses Hippocampus erectus in TR-1 and TR-2 after 5-week culture.

Discussion

Our results show that the young pairs of seahorses H. erectus had smaller brood size, poor offspring survivorship and growth, when compared with those from the old pair parents. However, they could improve their reproductive efficiency over few successive births. It was reported that in gulf pipefish Syngnathus scovelli, prior pregnancy of males could influence the latter reproduction through the post-copulatory sexual selection and sexual conflict between both sexes in a controlled breeding experiment (Paczolt and Jones, 2010). In this study, the mean brood size increased from 85.4±56.9 in the 1st birth to 465.9±136.4 in the 6th birth with the increase of the births in the young pairs of H. erectus. This is similar with the finding for H. kuda that large parents can reproduce much offspring (Dzyuba et al., 2006). In the wild, the brood size of H. erectus was large, with the maximum birth number of 1552 juveniles (Teixeira and Musick, 2001), which was significantly larger than that from the cultured pairs (Lin et al., 2008; present study). This is partly because the development and metabolic rate of seahorse changed under the low social interaction and low mating competition in the wild (Vincent, 1994a, b; Naud et al., 2009). To ascertain the relationship among the different births by the same male, we used the same body size of females to decrease the probability of the size-biased sexual selection and mate switching (Naud et al., 2009; Hunt et al., 2009; Paczolt and Jones, 2010). During the study, the fidelities were relatively low in most pairs during the reproductive process, so only 10 males among 75 pairs were found to mate with the same females during the 6 successive births. During the culture, pairs of H. erectus had short greeting and re-mating durations before or after each copulation, which significantly improved the reproductive rate. This result is similar to the investigation that the mate choices of males could be reinforced by females with more pronounced secondary sexual characters during post-copulatory sexual selection in S. scovelli (Paczolt and Jones, 2010).

During the study, the young couples were still growing and then they should have higher reproductive efficiency than before, and this might display a status that the number and survival rate of offspring significantly increased over successive births. The large sizes of brood pouches with the growth of the males were able to fit more eggs from females. This is consistent with the report that the old seahorses H. kuda with large body sizes had the larger brood size and higher offspring growth and survival rate (Dzyuba et al., 2006).

We found strong positive linear correlations between the male pouch size and number of offspring produced, as well as between the female standard body length and the number of offspring produced. As it provides for some nutrition, aeration and osmoregulation for developing embryos (Linton and Soloff, 1964; Berglund et al., 1986; Partridge et al., 2007), the surface area of the male's brood pouch is a limiting factor in the number of embryos that can be successfully incubated (Azzarello, 1991; Dzyuba et al., 2006). Therefore, the correlation between brood size and brood pouch length of male seahorses was positive. Paczolt and Jones (Paczolt and Jones, 2010) found a strong positive correlation between the number of eggs transferred and female size in S. scovelli. Similarly, female size in pipefish can affect the egg size and concentration of eggs within the male pouch (Berglund et al., 1986; Ahnesjö, 1992; Watanabe and Watanabe, 2002). However, the larger size males do not necessarily release larger sized offspring than those from smaller size males, and we have found that the body size of offspring was correlated with the brood size, gestation time and nutrient supply in the same males and females' investment (Lin et al., 2008; present study).

The mean number of offspring from the 2-year old female and 1-year old male pairs (302.4±113.8 per brood) was much higher than those from 1-year old pairs (89.6±36.9 inds/brood, n = 30, F2, 27 = 29.33, P = 0.000). This result is similar to the report that the female fecundity in pipefish increases over 2.5 times from the small (1-year old) to large females (2-year old) (Berglund and Rosenqvist, 1990). Compared with the 1-year old males, 2-year old males released more offspring after mating with 1-year or 2-year old females (increased 36.4% and 74.2% with 1-year and 2-year old females, respectively). In addition, the survivorship of offspring released from the 2-year old males was higher than that from the 1-year old males (Fig. 3B). This may be due to the increased size of brood pouches of the old males, or better function of the pouches in old males (Berglund et al., 1986; Azzarello, 1991; Carcupino et al., 2002; Dzyuba et al., 2006). This is similar to the report that the difference in the reproductive rate of male and female Syngnathus typhle increases as the fish age (Svensson, 1988). However, this does not display that the older seahorses have better quality offspring, and the quality is generally correlated with the brood pouch development, gestation time and parental investment (Vincent et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2008; Naud et al., 2009).

Masonjones and Lewis (Masonjones and Lewis, 2000) limited the sexual receptivity in female seahorses H. zosterae through isolating the females separately and then induced the sexual competition among the males, and their results showed that the females need a relatively long time investment to prepare to mate with the males. In this study, the mating competition among the male seahorses was strong and males sometimes courted with the females who were not ready. This is similar to the report that the male seahorses H. fuscus competed more intensively than females (Vincent, 1994a). Therefore, we guess that the mating competition among the males could influence the reproductive efficiency through affecting the gamete preparation of females (or decreasing the investment from the females). Data showed that the mean brood size in the couples of males and isolated females (552.7±150.4 per brood) was larger than that in the controls (467.8±141.2 per brood, n = 74, F1, 72 = 6.56, P = 0.013), although the survival rates of the offspring were not significantly different between the two groups (n = 74, F1, 72 = 0.27, P = 0.610). Furthermore, juveniles derived from the group of isolated females had a high growth rate and wide frequency distribution of body sizes. This partly is due to the quality of newborn offspring. Dzyuba et al. (Dzyuba et al., 2006) have shown that the quality conditions of parent seahorses could significantly influence the offspring growth and survival rates. Then, the frequency distributions of body sizes might be the criteria for assessing the quality of broodstock of the parent seahorses.

This is the first study of reproductive process for the young parent seahorses. Further research work should evaluate the evolutionary relationship of the reproductive formation (older broodstock with more mating experiences) between fish in the family Syngnathidae, and then investigate mechanism of potential reproduction and link the relationship among gonad development, mating competition and parental investment during the reproductive process.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Dong Zhang of Florida Institute of Technology and Dr Patricia Quintas of the Institute of Marine Research of the Spanish National Research Council (IIM-CSIC) for insightful discussion. This study was funded by the Innovation Program of Young Scientists of Chinese Academy of Sciences (KZCX2-EW-QN206), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30901109), Guangdong Oceanic and Fisheries Science and Technology Foundation (A200901E06, A201001D05) and the Science and Technology Program of Guangdong Province (2011B020307005).

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

References

- Ahnesjö I. (1992). Fewer newborn result in superior juveniles in the paternally brooding pipefish Syngnathus typhle L. J. Fish Biol. 41, Suppl sB53–63 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1992.tb03868.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azzarello M. Y. (1991). Some questions concerning the Syngnathidae brood pouch. Bull. Mar. Sci. 49, 741–747. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund A., Rosenqvist G. (1990). Male limitation of female reproductive success in a pipefish: effect of body-size differences. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 27, 129–133 10.1007/BF00168456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund A., Rosenqvist G., Svenson I. (1986). Reversed sex roles and parental energy investment in zygotes of two pipefish (Syngnathidae) species. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 29, 209–215 10.3354/meps029209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carcupino M., Baldacci A., Mazzini M., Franzoi P. (1997). Morphological organization of the male brood pouch epithelium of Syngnathus abaster Risso (Teleostea, Syngnathidae) before, during, and after egg incubation. Tissue Cell 29, 21–30 10.1016/S0040-8166(97)80068-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcupino M., Baldacci A., Mazzini M., Franzoi P. (2002). Functional significance of the male brood pouch in the reproductive strategies of pipefishes and seahorses: a morphological and ultrastructural comparative study on three anatomically different pouches. J. Fish Biol. 61, 1465–1480 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2002.tb02490.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock T. H., Parker G. A. (1992). Potential reproductive rates and the operation of sexual selection. Q. Rev. Biol. 67, 437–456 10.1086/417793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock T. H., Vincent A. C. (1991). Sexual selection and the potential reproductive rates of males and females. Nature 351, 58–60 10.1038/351058a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole K. S., Sadovy Y. (1995). Evaluating the use of spawning success to estimate reproductive success in a Caribbean reef fish. J. Fish Biol. 47, 181–191 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1995.tb01887.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dzyuba B., Van Look K. J., Cliffe A., Koldewey H. J., Holt W. V. (2006). Effect of parental age and associated size on fecundity, growth and survival in the yellow seahorse Hippocampus kuda. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 3055–3061 10.1242/jeb.02336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster S. J., Vincent A. C. J. (2004). Life history and ecology of seahorses: implications for conservation and management. J. Fish Biol. 65, 1–61 10.1111/j.0022-1112.2004.00429.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herald E. S. (1959). From pipefish to seahorse-a study of phylogenetic relationships. Proc. Calif. Acad. Sci. 29, 465–473. [Google Scholar]

- Hilomen-Garcia G. V., Delos Reyes R., Garcia C. M. H. (2003). Tolerance of seahorse Hippocampus kuda (Bleeker) juveniles to various salinities. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 19, 94–98 10.1046/j.1439-0426.2003.00357.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J., Breuker C. J., Sadowski J. A., Moore A. J. (2009). Male-male competition, female mate choice and their interaction: determining total sexual selection. J. Evol. Biol. 22, 13–26 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01633.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Job S. D., Do H. H., Meeuwig J. J., Hall H. J. (2002). Culturing the oceanic seahorse, Hippocampus kuda. Aquaculture 214, 333–341 10.1016/S0044-8486(02)00063-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koldewey H. J., Martin-Smith K. M. (2010). A global review of seahorse aquaculture. Aquaculture 302, 131–152 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.11.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q., Lu J., Gao Y., Shen L., Cai J., Luo J. (2006). The effect of temperature on gonad, embryonic development and survival rate of juvenile seahorses, Hippocampus kuda Bleeker. Aquaculture 254, 701–713 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2005.11.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q., Gao Y., Sheng J., Chen Q., Zhang B., Lu J. (2007). The effects of food and the sum of effective temperature on the embryonic development of the seahorse, Hippocampus kuda Bleeker. Aquaculture 262, 481–492 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.11.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q., Lin J., Zhang D. (2008). Breeding and juvenile culture of the lined seahorse, Hippocampus erectus Perry, 1810. Aquaculture 277, 287–292 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.02.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linton J. R., Soloff B. L. (1964). The physiology of the brood pouch of the male sea horse Hippocampus erectus. Bull. Mar. Sci. Gulf Caribb. 14, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lourie S. A., Vincent A. C. J., Hall H. J. (1999). Seahorses: An Identification Guide To The World's Species And Their Conservation, p. 214 London: Project Seahorse. [Google Scholar]

- Masonjones H. D. (1997). Relative parental investment of male and female dwarf seahorses, Hippocampus zosterae. Am. Zool. 37, 114a. [Google Scholar]

- Masonjones H. D., Lewis S. M. (2000). Differences in potential reproductive rates of male and female seahorses related to courtship roles. Anim. Behav. 59, 11–20 10.1006/anbe.1999.1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naud M. J., Curtis J. M. R., Woodall L. C., Gaspar M. B. (2009). Mate choice, operational sex ratio, and social promiscuity in a wild population of the long-snouted seahorse Hippocampus guttulatus. Behav. Ecol. 20, 160–164 10.1093/beheco/arn128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paczolt K. A., Jones A. G. (2010). Post-copulatory sexual selection and sexual conflict in the evolution of male pregnancy. Nature 464, 401–404 10.1038/nature08861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G. A., Simmons L. W. (1996). Parental investment and the control of sexual selection: predicting the direction of sexual competition. Proc. R. Soc. London B. Biol. Sci. 263, 315–321 10.1098/rspb.1996.0048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge C., Shardo J., Boettcher A. (2007). Osmoregulatory role of the brood pouch in the euryhaline Gulf pipefish, Syngnathus scovelli. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 147, 556–561 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripley J. L. (2009). Osmoregulatory role of the paternal brood pouch for two Syngnathus species. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 154, 98–104 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarratt A. (1996). Techniques for raising lined seahorses (Hippocampus erectus). Aquar. Front 3, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson I. (1988). Reproductive costs in two sex-role reversed pipefish species (Syngnathidae). J. Anim. Ecol. 57, 929–942 10.2307/5102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira R. L., Musick J. A. (2001). Reproduction and food habits of the lined seahorse, Hippocampus erectus (Teleostei: Syngnathidae) of Chesapeake Bay, Virginia. Rev. Bras. Biol. 61, 79–90 10.1590/S0034-71082001000100011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivers R. L. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection Sexual Selection And The Descent Of Man, 1871-1971. (ed. Campbell B.), pp. 136–179 Chicago: Aldine-Atherton. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent A. C. J. (1994a). Seahorses exhibit conventional sex roles in mating competition, despite male pregnancy. Behaviour 128, 135–151 10.1163/156853994X00082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent A. C. J. (1994b). Operational sex ratios in seahorses. Behaviour 128, 153–167 10.1163/156853994X00091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent A. C. J., Giles B. G. (2003). Correlates of reproductive success in a wild population of Hippocampus whitei. J. Fish Biol. 63, 344–355 10.1046/j.1095-8649.2003.00154.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent A. C. J., Marsden A. D., Evans K. L., Sadler L. M. (2004). Temporal and spatial opportunities for polygamy in a monogamous seahorse, Hippocampus whitei. Behaviour 141, 141–156 10.1163/156853904322890780 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S., Watanabe Y. (2002). Relationship between male size and newborn size in the seaweed pipefish, Syngnathus schlegeli. Environ. Biol. Fish. 65, 319–325 10.1023/A:1020510422509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A. B., Ahnesjö I., Vincent A. C., Meyer A. (2003). The dynamics of male brooding, mating patterns, and sex roles in pipefishes and seahorses (family Syngnathidae). Evolution 57, 1374–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods C. M. C. (2000). Improving initial survival in cultured seahorses, Hippocampus abdominalis Leeson, 1827 (Teleostei: Syngnathidae). Aquaculture 190, 377–388 10.1016/S0044-8486(00)00408-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woods C. M. C. (2003). Effect of stocking density and gender segregation in the seahorse Hippocampus abdominalis. Aquaculture 218, 167–176 10.1016/S0044-8486(02)00202-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton R. J. (1990). Ecology Of Teleost Fishes London: Chapman and Hall. [Google Scholar]