Abstract

Black men who have sex with men (BMSM) are disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic, yet few prevention interventions have been developed specifically for them. Recent studies suggest that the Internet is a promising intervention delivery avenue. We describe results from our formative work in developing a theory-based online HIV/STI prevention intervention for young BMSM including focus groups, semistructured interviews, and usability testing. The Intervention, HealthMpowerment.org, was created based on the Institute of Medicine’s integrated model of behavior change with extensive input from young BMSM. Key interactive Web site features include live chats, quizzes, personalized health and “hook-up/sex” journals, and decision support tools for assessing risk behaviors. Creating an interactive HIV/sexually transmitted infection web site for BMSM was a complex process requiring many adjustments based on iterative feedback throughout all development stages. Preliminary satisfaction, content acceptability, and usability findings support the use of the Internet to deliver risk reduction messages to young BMSM.

At least half of all new HIV seroconversions in the United States occur among adolescents or young adults; young men who have sex with men (MSM) are at particularly high risk (Koblin et al., 2000; Sifakis et al., 2007; Valleroy et al., 2000). Among MSM aged 13–29, Black MSM (BMSM) comprised the largest percentage (48%) of new HIV infections in 2006 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008a). From 2001 to 2006, the CDC (2008) reported a 93% increase in diagnoses among BMSM aged 13–24 years. The HIV prevalence among young BMSM is estimated to be four times that of White MSM (Valleroy et al., 2000).

Despite evidence that young BMSM are at high risk for HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), a recently conducted meta-analysis of 58 studies that examined the efficacy of HIV prevention interventions for MSM found that only two focused on BMSM and none were developed specifically for young BMSM (Johnson et al., 2009). Traditional HIV education efforts targeting MSM have been venue based, occurring in places where MSM meet other men (Hospers, Harterink, Van Den Hoek, & Veenstra, 2002). However, the Internet offers the opportunity to reach MSM who may not be accessible through “traditional” means and yet are engaging in high risk activities (Elford, Bolding, Davis, Sherr, & Hart, 2004). Several studies confirm that both White MSM and MSM of color are receptive to Internet-based data collection and interventions, such as chat discussions, individual outreach, educational services and message board forums (Bolding, Davis, Sherr, Hart, & Elford, 2004; Bull, McFarlane, & King, 2001; Fernandez et al., 2004; Klausner, Levine, & Kent, 2004; Rhodes, 2004; Turner, 2001).

The Internet has increasingly become a medium for the delivery of health behavior change interventions (Kalichman, Benotsch, Weinhardt, Austin, & Luke, 2002; Sciamanna et al., 2002) because it offers the ability to tailor individual messages to large numbers of people (Bull et al., 2001; Cassell, Jackson, & Cheuvront, 1998; Keller & Brown, 2002) and provide health information on demand (Keller, LaBelle, Karimi, & Gupta, 2002). Further, there is evidence that HIV/STI prevention education delivered over the Internet is effective (Bull et al., 2001). In response to a previously unrecognized epidemic of HIV infection affecting young BMSM in North Carolina (NC) (Hightow et al., 2005) who met sexual partners on the Internet we sought to design an interactive HIV/STI Web site for young BMSM. A successful Internet intervention for young BMSM has the potential to reach a unique, relatively marginalized high-risk segment of the population by using novel and innovative technology. We describe results from our formative work in developing a theory-based online HIV/STI prevention intervention for young BMSM.

METHODS

PARTICIPANTS

Men who were aged 18–30, self-identified as Black/African American, and reported having had anal or oral intercourse with another man in the past 12 months were eligible for participation. Participants for all aspects of Web site development and testing were recruited from the local community through online ads (via Face-book, Craigslist) and listservs, flyers, and through HIV and STI clinic providers.

FORMATIVE DATA COLLECTION

Three focus groups were conducted in confidential community spaces, lasting between 60 and 90 minutes. To protect their anonymity, participants used pseudonyms during the sessions. Each focus group was audio-recorded and a note taker recorded dialogue and nonverbal cues. The focus group sizes varied from five to eight participants and were conducted by staff experienced in working with young BMSM. A semistructured interview guide was used to facilitate the discussion, including sections concerning sexual communication, barriers to safer sex and HIV prevention, and HIV prevention intervention content and channels. Follow-up open-ended prompts were used to clarify respondents’ statements. Participants received a $50 incentive for their participation.

We also conducted semistructured interviews with eight different young BMSM to review and evaluate currently existing HIV/STI Web sites in terms of content, language and visual appeal. Participants were compensated $35 for participation. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

ANALYSIS

Two experienced qualitative analysts reviewed transcriptions from audio recordings of the focus groups and individual interviews. The qualitative analysis process —involving transcription, codebook development, data management, and analysis —was modeled after rigorous standards in the field of qualitative methods (Guest & MacQueen, 2008). The transcribed focus group data was uploaded into ATLAS.ti (Version 6.0) to assist with analysis. Data queries were run to aid in identifying themes and were compared with the initial themes identified by the analysts. The project team checked this coding for consistency and accuracy. The quotations reflect the general themes and opinions of a majority of the participants. Participants unanimously agreed on the concepts discussed, unless otherwise noted.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE WEB SITE

WEB SITE DESIGN

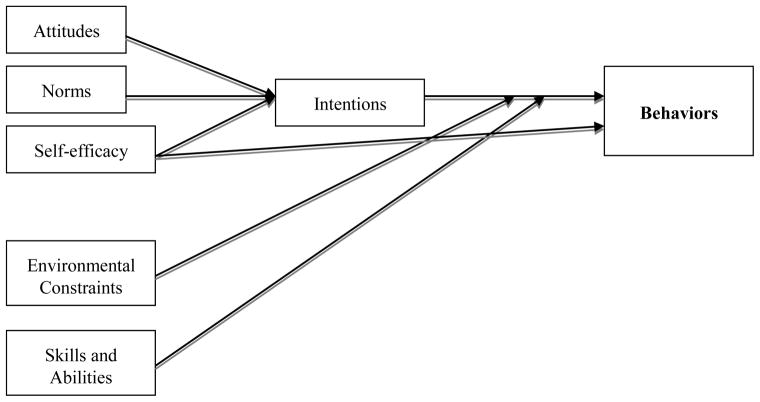

The intervention (HealthMpowerment.org) was based on the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) integrated model of behavior theory (Figure 1), which incorporates several leading theories of health behavior (Ajzen, 1985; Ajzen & Fishbein, 2004; Bandura, 1977, 2004; Fishbein & Ajzen, 2005; Rosenstock, Strecher, & Becker, 1994). This theory and related conceptual approaches have been used successfully to predict and explain a wide range of health behaviors, including smoking (Collins & Ellickson, 2004; Spijkerman, van den Eijnden, Vitale, & Engels, 2004), alcohol use (Gastil, 2000; Trafimow, 1996), and exercise (Blue, 1995; Hagger, Chatzisarantis, & Biddle, 2002). They have been especially effective in HIV prevention efforts (CDC, 1996; Fishbein, 2000; Fisher, Fisher, & Rye, 1995; Jemmott, Jemmott, & Fong, 1992; Kamb et al., 1998). Table 1 outlines the topic areas covered in HealthMpowerment.org, the model constructs applicable to each section and specific examples of how each construct was used throughout the website.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual Model of Constructs Influencing Engagement in Risky Sexual Behaviors.

TABLE 1.

Overview of HealthMpowerment Content and Model Constructs

| Section | Content | Constructs of Model Area Addressed | Example of How Construct Used to Elicit Behavior Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homepage | HIV information, relevant news stories, blog roll, rotating quote of the day, poll questions and results, Personalized Avatar | Attitudes and Norms | Provide YBMSM with personal and normative feedback |

| Norms | |||

|

| |||

| Mpower Yourself | Information on Men’s health and wellness, Safer Sex, Relationships, STDs, HIV, Drugs/Alcohol, Sexual Orientation in the form of articles, videos | Self-efficacy | Peer stories/videos model true life scenarios of Young BMSM living with HIV |

| Skills/Abilities | YBMSM obtain skills to recognize STI signs and symptoms | ||

| Skills/Abilities | Promote mastery learning through skills training (using condoms, negotiating safer sex) | ||

|

| |||

| Q and A | Answers to FAQs primarily focused on HIV/STDs, question submission forum, live chat with expert once/month | Attitudes | Provide informational component to increase awareness and knowledge of health risk and to convince YBMSM that they can change their behavior |

| Self-efficacy | |||

|

| |||

| House of Mpowerment | Quiz section with 4 levels of quizzes including topics such as: HIV & STDs, Men’s Health and Wellness, Drugs and Alcohol | Skills/Abilities | Promote mastery learning through quizzes which provide feedback on both correct and incorrect answers |

|

| |||

| Resources | National resources, local resources (for health, relationships, depression, etc), Blog rolls and news feeds | Environmental Constraints | Enhance confidence through communal motivations |

| Norms | Provides opportunities for advice and social support as YBMSM engages in new behaviors | ||

|

| |||

| Thinking It Through | Interactive decisional balance of facilitators and barriers to behavior change (condom use, drug/alcohol use); provides personalized strategies to address the barriers | Self-Efficacy | YBMSM identify cognitive- affective triggers for high-risk behavior; feedback provided enhances situational confidence |

|

| |||

| Your Journal | Options for general “creative writing” Journal popup, Hookup Journal, Health Journal Can record general thoughts, partner information, medical history (for both HIV-positive and negative), browse old entries | Self-Efficacy | Enhance confidence through journaling |

| Skills/Abilities | Develop skills to assess personal risk for HIV/STIs | ||

Note. YBMSM – young Black men who have sex with men; STI – sexually transmitted infection.

PROGRAM PRODUCTION

The Communication for Health Applications and Interventions (CHAI) Core was responsible for the technical design and programming of the HealthMpowerment (http://healthmpowerment.org) site. The CHAI Core provides service to research projects that are developing interventions aimed at promoting health and disease prevention. The Web site was tested on both laptop and desktop computers and on multiple browsers for both PC and Macintosh.

USABILITY TESTING

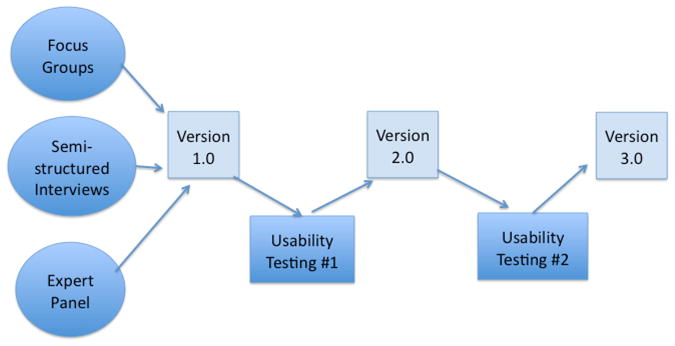

During development, two rounds of usability testing sessions were conducted, each lasting approximately 60 minutes (Figure 2). In Round 1 there were seven participants and in round two there were four participants; all were compensated $35 for their time. The mean age of the participants completing the usability testing was 22.4 years old.

FIGURE 2.

Steps in HealthMpowerment Development.

The testing sessions were conducted using a 15-inch Windows-based laptop computer with an attached mouse and Firefox as the browser. Sessions were conducted with a facilitator and a note taker present; all sessions were videotaped. Users were prompted to think aloud as they explored the site and to provide feedback on style and design considerations, images, and content. The videotaped sessions were analyzed to synthesize user input, describe usage patterns and themes, and identify common problems.

The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved all aspects of this research.

RESULTS

FOCUS GROUPS

Three important concepts emerged from our focus groups. First, participants felt that there was an overall lack of information around gay sexuality growing up at home as well as in school. Participants described negative experiences discussing sexuality and health with medical providers and found that most providers were not helpful when these men were dealing with their sexuality. The Internet was commonly used for finding sexual health information and exploring other aspects of sexuality. One participant remarked, “My first place was the Internet because I really didn’t have anyone to talk about me being gay. I had been to Google and searched ‘homosexual safe sex’ and ‘black safe sex.’” Participants perceived the Internet as convenient and time and cost efficient.

Second, the men had strong opinions regarding the efficacy of current or past prevention messages and campaigns; most participants agreed that fear-based prevention and “scare tactics” do not work and subsequently lead people to become defensive and therefore less receptive to the messages. However, participants did feel that actual statistics and consequences of having unsafe sex should be provided, including graphic descriptions and pictures of STIs. Many discussed the importance of incorporating safer sex into the larger context of the lives of young BMSM--something that had to be maintained continuously to be successful. As one young man remarked, “Safe sex is like just an occurrence. Safer sex is more like a lifestyle.” There was some disagreement within the groups about whether messages should be directed to BMSM or the larger audience of Black men in general. Use of a role model, who was “believable” and “credible” in terms of language, age, and dress was put forth as a possible prevention tool.

Third, participants discussed the essential components to be included in a Web site designed to engage and retain young BMSM. The “look and feel” of the Web site (e.g., color scheme, amount of text) was described as being the initial determinant of whether they would enter the site. Participants described hallmarks of a professional Web site as using rich color schemes, graphics and more elaborate typographic fonts. If a site looked “too white,” “too straight,” or “too cheap” participants said they would not give it a chance regardless of the information it contained. When asked to elaborate, users remarked that many HIV or STI Web sites they had previously visited did not promote that their site was inclusive of racial and sexual minorities. They felt that BMSM were the group most often ignored on home pages, and this omission was immediately appreciated and was a disincentive to continue exploring the site. They remarked that the most important characteristics of an HIV/STI Web site that make it look as if it was created specifically for BMSM were to include graphics or images of Black men; highlight health and news issues of importance to BMSM, and use colors, fonts, and language that are appealing to the target population. Regular updates of content were important as well as having interactive and personalized features presenting relevant information in a clear and concise fashion. Participants stated that having to spend too much time navigating through a site detracted from their overall experience and they would be unlikely to visit that site again. Websites that had a lengthy registration process or required a fee were summarily dismissed.

SEMISTRUCTURED INTERVIEWS

Five currently available web sites focused on HIV/STI prevention were reviewed. Users were guided in a semistructured fashion to evaluate features of these sites, including perceived purpose, intended audience, ease of use, interactivity, and general content/language. Although the interviewer had a list of topics and framework to be covered with participants, this process allowed topical trajectories in the conversation that might stray from the guide to explore additional relevant themes. In general, the following criticisms about the Web sites were voiced by a majority of participants: language tended to be either oversimplified (e.g., directed for a younger or uneducated group) or too technical (e.g., directed toward doctors or medical professionals); Web site design was not engaging or attractive, and participants felt the Web sites did not demonstrate a realistic understanding of the day-to-day issues that BMSM faced. Specifically, they related that many of the sites did not acknowledge the fact that HIV and STIs did not hold a priority position in the lives of many BMSM, especially those who did not have well paying jobs, supportive families and who were forced to deal with stigma related to their race and sexuality on a daily basis. In addition, they remarked that none of the Web sites seemed to be created specifically for Black gay men. Participants also reviewed options for a name and logo for our newly developed site, and a consensus was reached on HealthMpower-ment as embodying the full extent of the content being developed.

WEB SITE DESIGN

The research team and the CHAI Core spent 6 months developing the graphic design, navigation, architecture, and functionality of the site. We identified the following key features to be included based on formative data: the need (a) to make the language, main messages, and visual look of the site appealing and relevant to the target audience; (b) to allow users to have multiple ways to customize the site; (c) to integrate interactive elements into the site to engage users and provide entertainment along with education; and (d) to develop theory-based content and features (see Table 1).

USABILITY TESTING

The first round of usability testing was conducted to determine how HealthM-Powerment.org was received and if users were able to effectively navigate the Web site’s features and functions. Additions and changes were made to the site and a second round of testing was conducted. The usability findings, including participant feedback and changes made after the first round are described.

Users provided positive feedback on the overall graphic design and language of the site. The men unanimously rated the various interactive features of the Web site as their favorite parts, particularly the avatar (which included customizable features such as hair, body type, and clothing). Some participants felt that the “creative writing” journal could provide them a secure, confidential place to record their thoughts. Others did express some concerns about the privacy of the information they entered. One participant stated, “I’m afraid to write things down in a book, scared somebody might read it so I appreciate a place to get things out of my head and put it down, to express myself without expressing it to somebody else.” Another respondent remarked on the password-protected nature of the journal, “You should put in when you set up your account that this is for your eyes only. Because people are sensitive about putting stuff in, you know if they wanted everyone to know they would blog it.” Another participant explained how using the “hook up journal” might help him modify his risk behavior: “It’s pretty interesting. If I read what I’m doing, it registers. That could be really beneficial in terms of risk behavior because I have to look at who you’ve done it with, and everybody you’ve done it with--it makes it really real.” A few men (all of whom were HIV infected) suggested having an area where they could store health information and questions to ask their doctor.

The quiz language and graphics were modeled on the ballroom community (Murrill et al., 2008; Sanchez, Finlayson, Murrill, Guilin, & Dean, 2009), an underground subculture in which people “walk” (i.e., compete) for trophies and prizes at events known as “balls.” Design elements included a “runway” background, Olympics style numeric scoring (“10s”) for correct answers, and trophy icons as participants proceed through the quiz levels. Many appreciated references to the “ball culture.” As one participant stated, “The language seems consistent with the broad spectrum of Black gay men that I’ve encountered. Your ‘10s’ come from the house scene--‘are you ready to walk and show?’ I like that language.” Although participants understood and appreciated the desire to make the Web site entertaining and appealing, they were also very aware of the importance of the informational aspect of the site, and valued the breadth of the educational content. Another participant remarked, “It has all the information that a gay male person should know. What can we do and what can we not do. I think you guys are right on top of it. It has a lot of information. My friends, they need to know all this.”

Beyond the fun, however, many of the participants appreciated the chance to be challenged, test their knowledge and be provided with personalized risk reduction feedback through the decisional balance tool and the quizzes. Most participants went through several levels of the quizzes and spent a long time in this area. They liked the display of detailed answers, whether the question was answered correctly or not, and that humor was incorporated into the questions. One participant said, “The quiz is fabulous. I would love to take the quiz, I’d be here all day, especially on relationships, and safer sex.” Another remarked, “Everybody needs to look at House of Mpowerment [the quiz section]--you think you know a lot, and realize you don’t.”

The FAQ/Ask the Expert was another section that generated positive comments. Users wanted to know the details of how their questions would be answered, by whom, and within what timeframe. They talked about the lack of good information sources and the need for a place where people could submit their questions and receive answers in a somewhat anonymous setting. As one participant stated, “The Q&A section is really good—I have questions myself sometimes, and I know some friends who ask me questions, and I really don’t know how to answer that, but now I can refer you to someone who might know how to.”

Improvements and changes made based on our findings from Round 1 included (a) streamlining the setup process; (b) adding more options for customizing the avatar including skin tone, glasses, and different options for facial hair; (c) revising placement of content on the home page to make the overall look more appealing, colorful and to immediately motivate users to move past the home page and explore the content within; (d) including a second level of password protection for the journal feature to increase security; (e) including some additional content areas such as information about basic sexuality, how to address disclosure of HIV status, how and where to get tested, proper condom use, and issues dealing with sexual orientation (for both gay and non-gay identified BMSM); (f) adding additional decisional balances focused on drug and alcohol use and Internet sex seeking; and (g) adding more interactive pieces such as a health journal. All of these changes were well received by participants in the second round of usability testing.

DISCUSSION

This article describes the development of a theory-based HIV/STI behavior change Internet intervention designed for young BMSM, a group that continues to be deeply affected by HIV (CDC, 2008a; G. A. Millett, Flores, Peterson, & Bakeman, 2007). Although previous studies have found that computer-based interventions are efficacious in reducing HIV related sexual risks (Bowen, Horvath, & Williams, 2007; Noar, Black, & Pierce, 2009; Ybarra & Bull, 2007), to date, no intervention has been developed specifically for young BMSM (Noar et al., 2009). Based on prior studies of successful Internet interventions, we aimed to develop a Web site based on theory (Vandelanotte, Spathonis, Eakin, & Owen, 2007) that provided tailored or personal feedback (Noar, Benac, & Harris, 2007; Noar et al., 2009). A comprehensive Internet-based HIV-risk reduction intervention for a population that is marginalized, stigmatized, and hard to reach through traditional means could have a significant impact on the epidemic.

We relied extensively on input from members of the target population in all stages of Web site creation to ensure the intervention would meet the needs of those for whom it was created. Overall, our formative research found that young BMSM are not being taught how to practice safe sex within the context of same sex relationships from either their families or in schools and thus are relying on the Internet for basic information. However, currently available HIV/STI Web sites are not fully meeting their prevention needs. Participants wanted credible, real-life information presented within the context of overall health and wellness. We developed HealthM-powerment.org to fill this void and address issues relevant in the lives of these men, acknowledging explicitly that staying healthy is more than just about practicing safe sex. Through participation in the intervention we hope to increase young BMSM’s overall sense of self-worth, and thereby improve their participation in health promotion behaviors.

Tailoring has been shown to successfully influence adoption of preventative health behaviors (Noar et al., 2007). Further, the use of culturally sensitive materials that reflect relevant community norms is widely recognized as an important requirement for HIV-related interventions with racial and ethnic minority groups (DiClemente et al., 2004; Fennell, 1997; Jemmott, Jemmott, & Fong, 1992; Jemmott, Jemmott, Fong, & McCaffree, 1999; Kalichman & Coley, 1995; Kalichman, Kelly, Hunter, Murphy, & Tyler, 1993; McLean, 1994; O’Donnell, O’Donnell, San Doval, Duran, & Labes, 1998; Stevenson & Davis, 1994). Understanding cultural backgrounds and life experiences of communities and individuals will enhance the current knowledge-base for designing and evaluating interventions (Institute). Most empirically tested interventions have been targeted toward gay-identified BMSM; these may not be adequate to reach diverse groups of BMSM. More specifically, non-gay-identified BMSM and Black men who have sex with men and women may have HIV prevention needs that are different from those of other BMSM, and these needs may not be obvious. Prevention messages that reflect the heterogeneity that exists among BMSM in terms of identity and sexual expression are more likely to be successful (Brown, 1992; Myrick, 1999; Rogers et al., 1995). Our formative research led to the incorporation of intervention components and topics to the Web site that are culturally meaningful and developmentally appropriate for young BMSM. Some of these needs include dealing with the dual identity of being both gay and Black; high levels of perceived racism, homophobia, and cultural/familial beliefs about masculinity and social isolation and rejection from the Black community and church owing to their gay identity and/or HIV status. In designing HealthMpowerment.org, we have tried to be cognizant of these issues, and members of the target population indicated we are moving in the right direction in designing a Web site that is both functional and relevant for the health and prevention issues that they face. The positive responses to the Web site might be due to social desirability bias if participants were responding in the presence of a project staff member, but we tried to minimize this by clearly letting participants know that there were no right or wrong answers and that we truly wanted honest feedback to improve the Web site.

We chose to develop this intervention for BMSM between the ages of 18 and 30. Although we recognize that this age range encompasses different developmental stages, this decision was based on national and local epidemiological data that underscore the high rates of HIV infection among BMSM within this age range. We have tried to be sensitive throughout the Web site to include articles and exercises relevant to all stages of identity development.

Our usability testing helped to introduce innovative components into the Web site. The men readily articulated their views on the general design and content. A feature that participants identified as missing was a community networking function that would allow users to post responses, leave comments, chat, or contribute to a group blog. Additionally, several users commented that they felt that certain sections of the site would be useful to have available on a mobile device. Based on user feedback, we took care to avoid confusing medical jargon and lengthy passages of text and we have tried to include enough interactive features to keep the target audience engaged and motivated to return to the site more than once.

In summary, we have tried to create an entertaining, captivating and stimulating Web site that successfully delivers key messages around HIV/STI prevention and overall health and wellness. Tailored, culturally appropriate prevention efforts that focus on the unique prevention and treatment needs of young BMSM are greatly needed. In a comprehensive review of HIV prevention research targeted toward BMSM, Millett, Malebranche, and Peterson (2007) noted there was a clear deficit of proven effective HIV prevention interventions for BMSM given their disproportionate disease burden. Our next steps are to incorporate additional features into HealthMpowerment.org, including a mobile phone component, as suggested by participants and evaluate the site for feasibility and acceptability in a small sample of young BMSM with the hopes of testing this intervention’s efficacy in a larger, more geographically diverse population.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by funding provided by a National Institute of Mental Health K23 award, 5K23MH075718-02, and by National Institutes of Health Grant 1K24HD059358-01

Contributor Information

Lisa B. Hightow-Weidman, The Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, UNC School of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Beth Fowler, The Communication for Health Applications and Interventions Core, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Jessica Kibe, The Communication for Health Applications and Interventions Core, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Regina McCoy, The Communication for Health Applications and Interventions Core, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Emily Pike, The Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, UNC School of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Molly Calabria, The Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, UNC School of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Adaora Adimora, The Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, UNC School of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

References

- Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Bechmann J, editors. Action control: From cognition to behavior. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Questions raised by a reasoned action approach: Comment on Ogden (2003) Health Psychology. 2004;23(4):431–434. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education, and Behavior. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue CL. The predictive capacity of the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior in exercise research: An integrated literature review. Research in Nursing and Health. 1995;18(2):105–121. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolding G, Davis M, Sherr L, Hart G, Elford J. Use of gay Internet sites and views about online health promotion among men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2004;16(8):993–1001. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen AM, Horvath K, Williams ML. A randomized control trial of Internet-delivered HIV prevention targeting rural MSM. Health Education Research. 2007;22(1):120–127. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WJ. Cuture and AIDS education: Reaching high-risk heterosexuals in Asian American communities. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 1992;20:274–291. [Google Scholar]

- Bull SS, McFarlane M, King D. Barriers to STD/HIV prevention on the Internet. Health Education Research. 2001;16(6):661–670. doi: 10.1093/her/16.6.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassell MM, Jackson C, Cheuvront B. Health communication on the Internet: an effective channel for health behavior change? Journal of Health Communication. 1998;3(1):71–79. doi: 10.1080/108107398127517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Community-level prevention of human immunodeficiency virus infection among high-risk populations: The AIDS Community Demonstration Projects. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1996;45(RR–6):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Subpopulation estimates from the HIV Incidence Surveillance System--—United States, 2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008a;57(36):985–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in HIV/AIDS diagnoses among men who have sex with men—33 States, 2001—2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008b;57(25):681–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Ellickson PL. Integrating four theories of adolescent smoking. Substance Use and Misuse. 2004;39(2):179–209. doi: 10.1081/ja-120028487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, Lang DL, Davies SL, Hook EW, III, et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(2):171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elford J, Bolding G, Davis M, Sherr L, Hart G. Web-based behavioral surveillance among men who have sex with men: A comparison of online and offline samples in London, UK. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;35(4):421–426. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennell R. Health behaviors of students attending historically black colleges and universities: Results from the National College Health Risk Behavior Survey. Journal of American College Health. 1997;46(3):109–117. doi: 10.1080/07448489709595596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez MI, Varga LM, Perrino T, Collazo JB, Subiaul F, Rehbein A, et al. The Internet as recruitment tool for HIV studies: viable strategy for reaching at-risk Hispanic MSM in Miami? AIDS Care. 2004;16(8):953–963. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M. The role of theory in HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2000;12:273–278. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Theory-based behavior change interventions: comments on Hobbis and Sutton. Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10(1):27–31. doi: 10.1177/1359105305048552. discussion 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WA, Fisher JD, Rye BJ. Understanding and promoting AIDS preventive behavior: Insights from the theory of reasoned action. Health Psychology. 1995;14:255–264. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastil J. Thinking, drinking, and driving: Application of the theory of reasoned action to DWI prevention. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2000;30(11):2217–2232. [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, MacQueen K, editors. Handbook for team-based qualitative research. Vol. 1. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hagger MS, Chatzisarantis NLD, Biddle SJH. A meta-analytic review of the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior in physical activity: an examination of predictive validity and the contribution of additional variables. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2002;24:3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hightow LB, MacDonald PD, Pilcher CD, Kaplan AH, Foust E, Nguyen TQ, et al. The unexpected movement of the HIV epidemic in the Southeastern United States: transmission among college students. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;38(5):531–537. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000155037.10628.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospers HJ, Harterink P, Van Den Hoek K, Veenstra J. Chatters on the Internet: A special target group for HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2002;14(4):539–544. doi: 10.1080/09540120208629671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute. of Medicine. Speaking of health: Assessing health communication strategies for diverse populations. 2002 Retrieved August 1, 2010 from http://www.nap.edu/books/0309072719/html/ [PubMed]

- Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Reductions in HIV risk-associated sexual behaviors among Black male adolescents: Effects of an AIDS prevention intervention. American Journal of Public Health. 1992b;82(3):372–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Smoak ND, Lacroix JM, Anderson JR, Carey MP. Behavioral interventions for African Americans to reduce sexual risk of HIV: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;51(4):492–501. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a28121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Benotsch EG, Weinhardt LS, Austin J, Luke W. Internet use among people living with HIV/AIDS: Association of health information, health behaviors, and health status. AIDS Educcation and Prevention. 2002;14(1):51–61. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.1.51.24335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Coley B. Context framing to enhance HIV-antibody-testing messages targeted to African American women. Health Psychology. 1995;14(3):247–254. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Kelly JA, Hunter TL, Murphy DA, Tyler R. Culturally tailored HIV-AIDS risk-reduction messages targeted to African-American urban women: Impact on risk sensitization and risk reduction. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(2):291–295. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, Jr, Rhodes F, Rogers J, Bolan G, et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial. Project RESPECT Study Group. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280(13):1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SN, Brown JD. Media interventions to promote responsible sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39(1):67–72. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SN, LaBelle H, Karimi N, Gupta S. STD/HIV prevention for teenagers: a look at the Internet universe. Journal of Health Communication. 2002;7(4):341–353. doi: 10.1080/10810730290088175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausner JD, Levine DK, Kent CK. Internet-based site-specific interventions for syphilis prevention among gay and bisexual men. AIDS Care. 2004;16(8):964–970. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Torian LV, Guilin V, Ren L, MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA. High prevalence of HIV infection among young men who have sex with men in New York City. AIDS. 2000;14(12):1793–1800. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200008180-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean DA. A model for HIV risk reduction and prevention among African American college students. Journal of American College Health. 1994;42(5):220–223. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1994.9938447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett G, Malebranche D, Peterson JL. HIV/AIDS prevention research among Black men who have sex with men: Current progress and future directions. In: Meyer IM, Northridge ME, editors. The health of sexual minorities: Public health perspectives on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered populations. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: A meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21(15):2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrill CS, Liu KL, Guilin V, Colon ER, Dean L, Buckley LA, et al. HIV prevalence and associated risk behaviors in New York City’s house ball community. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(6):1074–1080. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.108936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrick R. In the life: Culture-specific HIV communication programs designed for African American men who have sex with men. Journal of Sex Research. 1999;36(2):159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(4):673–693. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Black HG, Pierce LB. Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: A meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23(1):107–115. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c5500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell CR, O’Donnell L, San Doval A, Duran R, Labes K. Reductions in STD infections subsequent to an STD clinic visit. Using video-based patient education to supplement provider interactions. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1998;25(3):161–168. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199803000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD. Hookups or health promotion? An exploratory study of a chat room-based HIV prevention intervention for men who have sex with men. AIDS Education Prevention. 2004;16(4):315–327. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.4.315.40399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM, Dearing JW, Rao N, Campo S, Meyer G, Betts GJF, et al. Communication and community in a city under siege: The AIDS epidemic in San Francisco. Communication Research. 1995;22:664–668. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. The health belief model and HIV risk behavior change. In: DiClemente RJ, Peterson JL, editors. Preventing AIDS: Theories and methods of behavioral interventions. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez T, Finlayson T, Murrill C, Guilin V, Dean L. Risk Behaviors and Psychosocial Stressors in the New York City house ball community: A comparison of men and transgender women who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 2010. 2009 Apr 14;(2):351–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9610-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciamanna CN, Lewis B, Tate D, Napolitano MA, Fotheringham M, Marcus BH. User attitudes toward a physical activity promotion Web site. Preventitive Medicine. 2002;35(6):612–615. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifakis F, Hylton JB, Flynn C, Solomon L, Mackellar DA, Valleroy LA, et al. Prevalence of HIV infection and prior HIV testing among young men who have sex with men. The Baltimore Young Men’s Survey. AIDS and Behavior, 2010. 2007 Apr 14;(4):904–12. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9317-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spijkerman R, van den Eijnden RJ, Vitale S, Engels RC. Explaining adolescents’ smoking and drinking behavior: The concept of smoker and drinker prototypes in relation to variables of the theory of planned behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(8):1615–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, Davis G. Impact of culturally sensitive AIDS video education on the AIDS risk knowledge of African-American adolescents. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1994;6(1):40–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trafimow D. The Importance of attitudes in the prediction of college students’ intentions to drink. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1996;26(24):2167–2188. [Google Scholar]

- Turner W. ACT UP slams chat room based surveillance as “dubious use of taxpayer dollars”. 2001 Retrieved August 1, 2010, from http://www.glaa.org/archive/2007/actup-2dohonstdgrant1029.shtml.

- Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM, Rosen DH, McFarland W, Shehan DA, et al. HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. Young Men’s Survey Study Group. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(2):198–204. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandelanotte C, Spathonis KM, Eakin EG, Owen N. Website-delivered physical activity interventions a review of the literature. American Journal of Preventitive Medicine. 2007;33(1):54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra ML, Bull SS. Current trends in Internet- and cell phone-based HIV prevention and intervention programs. Current HIV/AIDS Report. 2007;4(4):201–207. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]