Abstract

Riboflavin serves as a precursor for flavocoenzymes (FMN and FAD) and is essential for all living organisms. The two committed enzymatic steps of riboflavin biosynthesis are performed in plants by bifunctional RIBA enzymes comprised of GTP cyclohydrolase II (GCHII) and 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase (DHBPS). Angiosperms share a small RIBA gene family consisting of three members. A reduction of AtRIBA1 expression in the Arabidopsis rfd1mutant and in RIBA1 antisense lines is not complemented by the simultaneously expressed isoforms AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3. The intensity of the bleaching leaf phenotype of RIBA1 deficient plants correlates with the inactivation of AtRIBA1 expression, while no significant effects on the mRNA abundance of AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3 were observed. We examined reasons why both isoforms fail to sufficiently compensate for a lack of RIBA1 expression. All three RIBA isoforms are shown to be translocated into chloroplasts as GFP fusion proteins. Interestingly, both AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3 have amino acid exchanges in conserved peptides domains that have been found to be essential for the two enzymatic functions. In vitro activity assays of GCHII and DHBPS with all of the three purified recombinant AtRIBA proteins and complementation of E. coli ribA and ribB mutants lacking DHBPS and GCHII expression, respectively, confirmed the loss of bifunctionality for AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3. Phylogenetic analyses imply that the monofunctional, bipartite RIBA3 proteins, which have lost DHBPS activity, evolved early in tracheophyte evolution.

Keywords: riboflavin, flavo-coenzyme, bifunctional enzyme, Arabidopsis, FAD and FMN

1. Introduction

Riboflavin (vitamin B2) is synthesized de novo in plants, fungi, archaea and numerous bacteria, while animals depend on dietary supply [1]. Riboflavin is the precursor for the synthesis of flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), which are essential cofactors for numerous enzymes (e.g., dehydrogenases, oxidases, reductases) that participate in one- and two-electron oxidation-reduction processes critical for major metabolic pathways in all organisms. In plants, these cofactors are required for photosynthesis, mitochondrial electron transport, fatty acid oxidation, photoreception, DNA repair, metabolism of other cofactors and biosyntheses of numerous secondary metabolites [2,3].

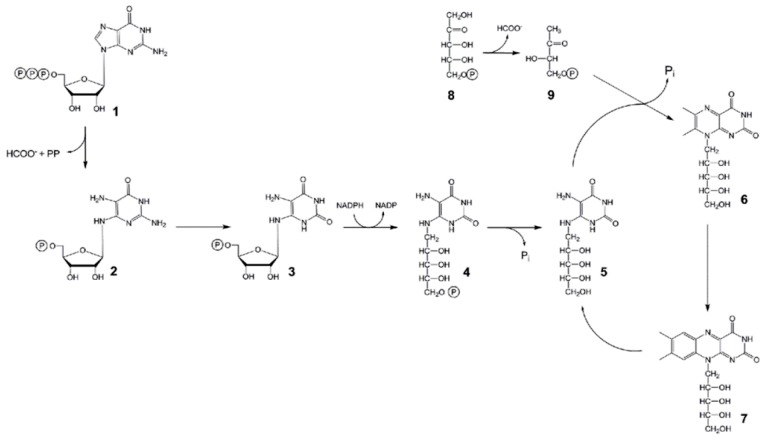

The riboflavin biosynthesis pathway is similar in plants, yeast and bacteria [1,4]. Riboflavin is synthesized by a series of seven distinct enzymatic reactions from GTP (1 in Figure 1) and ribulose 5-phosphate (8), and then phosphorylated to FMN and adenylated to FAD. The reactions of riboflavin biosynthesis are described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Biosynthesis of riboflavin. Riboflavin biosynthesis is initiated by the enzymes GTP cyclohydrolase II (GCHII) and 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase (DHBPS) converting GTP (1) into 2,5-diamino-6-ribosylamino-4(3H)-pyrimidinone 5′-phosphate (2) and ribulose-5-phosphate into 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone 4-phosphate (9), respectively. Both 2 and 9 are the first committed substrates of the riboflavin biosynthetic pathway. Following the biosynthetic pathway to riboflavin (7), 2 is consecutively modified to 5-amino-6-ribosylamino-2,4(1H,3H)-pyrimidine 5′-phosphate (3), 5-amino-6- ribitylamino-2,4(1H,3H)-pyrimidinedione 5′-phosphate (4) and 5-amino-6-ribitylamino- 2,4(1H,3H)-pyrimidinedione (5) by deaminase, reductase and phosphatase reactions, respectively. At present, it is still not clear if one specific phosphatase or several less specific enzymes are implemented in the dephosphorylation of 4. 5 is condensed with 9 by the enzyme lumazine synthase giving rise to 6,7-dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine (6). Finally, riboflavin synthase catalyzes a dismutation reaction of two molecules of 6 to form 7 yielding 5 as a byproduct, which again serves as substrate for lumazine synthase.

Detailed information is available about biochemistry and the regulation of vitamin B2 and flavin nucleotide biosynthesis in bacteria and fungi. Although plants are a major source of riboflavin for animals, only a few studies were dedicated to riboflavin biosynthesis in plants, its regulation and subcellular localization. Thus, early studies reported an activity converting 6 to 7 in leaves [5] and a partially purified enzyme from spinach [6]. Then, based on sequence similarity to their microbial homologs, several cDNA sequences of the pathway have been cloned from plants [3,7–11] providing strong evidence that riboflavin biosynthesis proceeds through almost the same steps in plants, fungi and bacteria.

Based on experimental and bioinformatic evidence, the enzymes of plant riboflavin biosynthesis are considered to reside in plastids [8–11]. In continuation of the pathway, phosphorylation of riboflavin to FMN and subsequent adenylation to FAD are catalyzed by the enzymes riboflavin kinase and FAD synthetase, respectively, in the presence of ATP and Mg2+[12–14]. These proteins have been found in plants to be not solely located in plastids [14]. Nevertheless, the subcellular distribution of enzymes catalyzing flavin nucleotide biosynthesis and hydrolysis is neither completely understood in plants nor other eukaryotic organisms.

The two initial reactions in riboflavin biosynthesis, starting at substrates 1 and 9 (Figure 1), respectively, are accomplished in several eubacteria, including E. coli, by genes designated ribA and ribB which encode monofunctional GCHII and DHBPS proteins, respectively [15,16]. However, other prokaryotes, such as Bacillus subtilis or cyanobacteria, produce a bifunctional RibA protein consisting of a DHBPS region in its N-terminal and a GCHII region in its C-terminal part [15].

In addition to the known Arabidopsis RIBA gene (hereafter designated AtRIBA1) [10], two additional genes encoding putatively bifunctional RIBA proteins (AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3) are present in the A. thaliana genome. In two previous reports, the AtRIBA1 mutant rfd1 has been characterized by a dramatic down-regulation of AtRIBA1 expression and reduced flavin contents in planta[17,18]. Hence, the homologous genes AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3 were not able to complement the loss of AtRIBA1. A detailed look at the amino acid sequences of AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3 revealed that several conserved amino acid residues are missing, either in the RIBA2 or the RIBA3 sequence, which are considered to be essential for the catalytic properties of enzymes [17]. To gain further insights into the functions of the AtRIBA proteins we performed expression studies of the three RIBA genes, assayed the enzymatic activities of the three recombinant AtRIBA isoforms in vitro and complemented E. coli ribA and ribB knock-out mutants.

2. Results

2.1. Expression Patterns of AtRIBA Genes

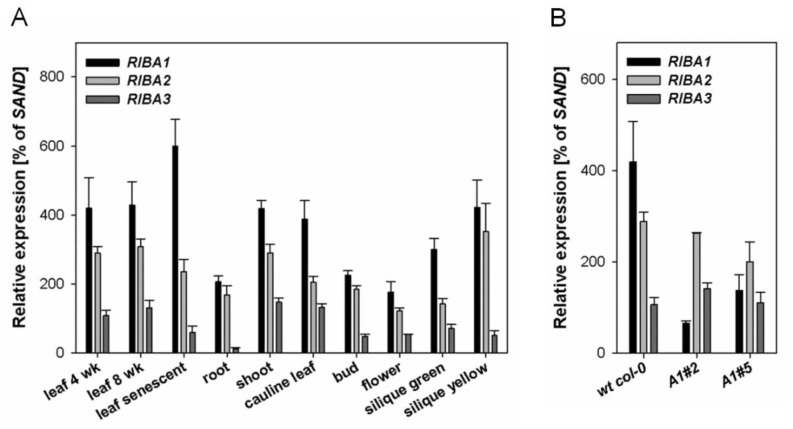

To examine the metabolic impact of the three RIBA isoforms identified in A. thaliana, the relative transcript amounts of the three AtRIBA homologs were assessed using qRT-PCR analyses in different tissues and developmental stages of wild-type plants. Transcripts of the three RIBA homologs accumulate in all analyzed tissues, but transcript levels were different (Figure 2A). The accumulation of AtRIBA1 mRNA exceeded the transcript levels of AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3 in all organs and developmental stages analyzed. However, the widely parallel accumulation of AtRIBA transcripts does not indicate a strong tissue specificity of gene expression of single members of the AtRIBA gene family.

Figure 2.

qPCR analyses of AtRIBA genes. (A) transcript accumulation of Arabidopsis RIBA genes was examined in different tissue types and (B), in two representative AtRibA1 antisense lines with intermediate (A1#5) and strong bleaching phenotype (A1#2), respectively. Expression was calculated relative to mRNA levels of SAND (At2g28390).

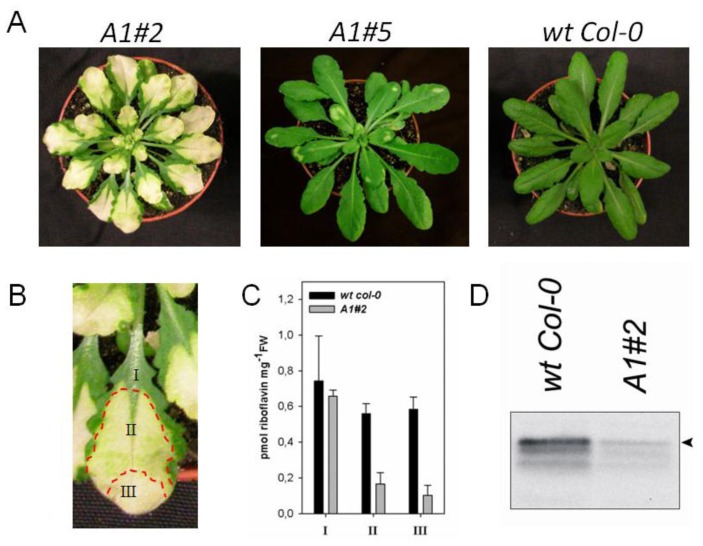

2.2. Downregulation of AtRIBA1 Causes a Bleached Phenotype

A strong down-regulation of the AtRIBA1 gene expression in the Arabidopsis rfd1 mutant correlated with a bleached phenotype [18]. Seedlings were unable to grow photoautotrophically on soil and their growth was abandoned in sugar-supplemented media after several weeks. Interestingly, the bleaching phenotype of the seedlings is not counterbalanced by the simultaneous AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3 expression, which remains at wild-type levels in rfd1[17]. For a gradual reduction of riboflavin biosynthesis, several transgenic lines with AtRIBA1 antisense RNA expression under control of the CaMV 35S promoter were generated (Figure 3A). RIBA mRNA levels were determined in rosette leaves of two representative AtRIBA antisense lines (A1#2 and A1#5) displaying different degrees of pigment deficiency. While the intensity of the phenotype in the two selected lines correlates with reduced AtRIBA1 transcript levels, AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3 are expressed at levels comparable to wild-type tissue (Figure 2B). Hence, the expression of the latter isoforms does not prevent the deficiency in riboflavin biosynthesis and the decline of AtRIBA1 expression in Arabidopsis was not compensated for at the transcriptional level by modified activity of the homologous genes.

Figure 3.

Phenotype of antisense AtRIBA1 plants. (A) Different degrees of bleaching are the result of AtRIBA1 antisense expression. Plants displaying a moderate antisense phenotype (left panel) start to bleach partially at the tip of leaves in the rosette stage, while individuals with a stronger reduction in AtRIBA1 transcript amounts display white inner rosette leaves and shoot apical meristem (middle). A Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col-0) wild-type plant of the same age is depicted in the right panel. (B) For HPLC analyses, leaves of line A1#2 were harvested and dissected as indicated. I: green, II: medium, III: white pigmentation. Reference samples were collected from comparable regions of wild-type plants. (C) Leaf regions depicted in (B) were subjected to flavin extraction and analyzed for the content of riboflavin using HPLC. (D) Immunodetection of AtRIBA protein in whole leaf extracts of line A1#2 and wild-type Col-0 control using anti-RIBA1 specific antiserum. Both samples represent identical fresh weight amounts. Although the antiserum recognizes all three AtRIBA isoforms, the upper band (arrow head) was shown to represent AtRIBA1 by an analysis of overexpressing lines (data not shown).

The phenotypic alterations of individuals with a severe phenotype, including line A1#2, were compared between three leaf sections. While the leaf base (Sample I in Figure 3B,C) was similar to a wild type, a progressive loss of pigmentation was observed towards the leaf tip (samples II and III). In these leaf sections, a gradual reduction of riboflavin (Figure 3C) was observed. AtRIBA1 protein levels were strongly decreased in A1#2 leaves (Figure 3D), agreeing with the observed reduction in mRNA amounts.

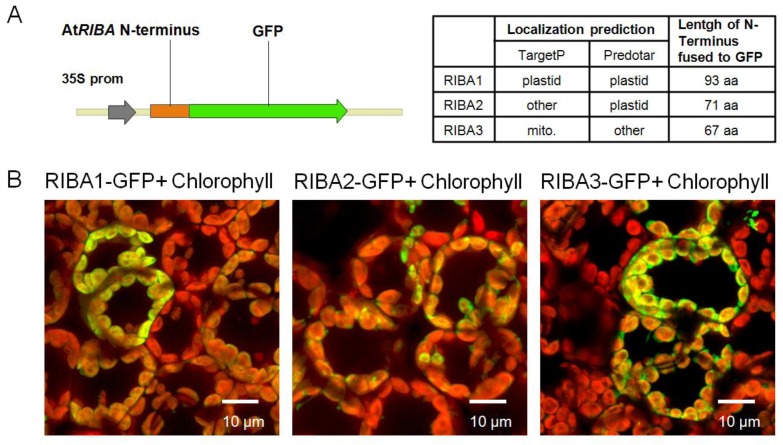

2.3. Subcellular Localization of AtRIBA Proteins

Since all three AtRIBA genes are constantly expressed, the observed AtRIBA1 depletion phenotype of rfd1[18] and the antisense lines depicted in Figure 3A could be explained by spatial separation of AtRIBA proteins in different subcellular compartments.

To address the localization of the three AtRIBA proteins, iPSORT [19], TargetP [20] and Predotar [21] algorithm were used for targeting predictions of their subcellular localization (Figure 4A). The prediction hinted at the existence of an N-terminal RIBA transit peptide and either a plastidic or mitochondrial localizations. We examined in situ targeting of the three RIBA homologs by CLSM-mediated visualization of transiently expressed green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion proteins after transformation of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Based on predictions by TargetP, three different gene constructs encoding the putative transit peptides of AtRIBA1-3 were fused to 5′-end of the GFP-encoding sequence (Figure 4A). The co-localization of chlorophyll and GFP fluorescence observed for all three RIBA-GFP fusions (Figure 4B) clearly demonstrates that all AtRIBA N-termini contain plastid targeting signals.

Figure 4.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP) localization experiments. (A) The amino terminal sequences comprising the putative transit peptides were translationally fused to the N-terminus of GFP. Targeting properties were predicted using TargetP and Predotar. The lengths of the AtRIBA aminotermini tested experimentally are indicated. (B) RIBA-GFP fusions were expressed transiently in Agrobacterium-infiltrated Nicotiana benthamiana leaves and visualized in mesophyll cells using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy. The three panels show merged images of GFP and chlorophyll fluorescence indicating that green fluorescence localizes within the plastid compartment for all three RIBA-GFP fusion constructs investigated.

2.4. In vitro Enzyme Assays with Recombinant AtRIBA Proteins

For detailed comparative characterization of AtRIBA enzymes in vitro, all three RIBA-encoding sequences were expressed in E. coli. The design of the artificial RIBA sequences included adaptation to E. coli codon usage and addition of an N-terminal His–tag (Data S1). All RIBA proteins specified by newly generated plasmid constructs lacked the plant-specific N-terminal sequence including the transit peptide. Thus, in comparison to the wild-type protein precursor sequences the recombinant proteins lacked the first 127 (AtRIBA1), 105 (AtRIBA2) or 100 amino acids (AtRIBA3), respectively (cf. alignment in Figure S1B in [17]).

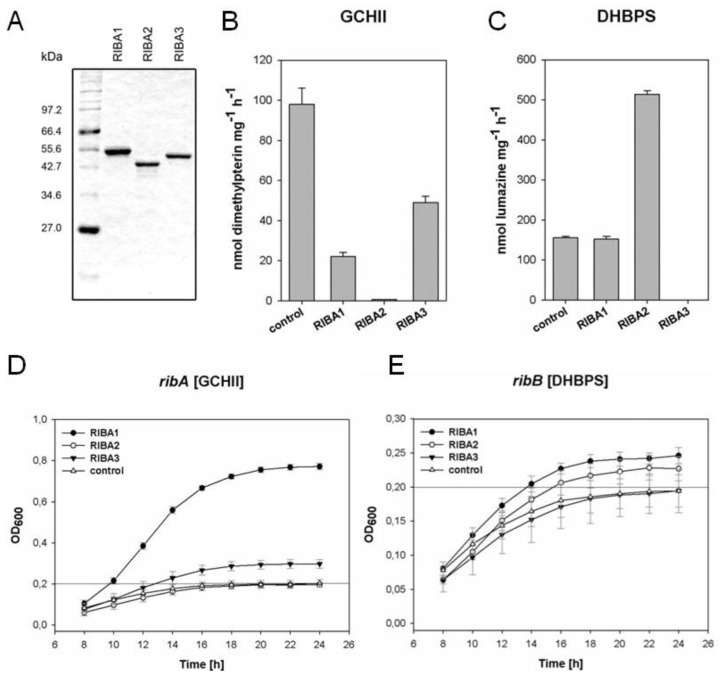

All three over-produced recombinant RIBA proteins were purified by FPLC using metal affinity chromatography. SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the purified recombinant AtRIBA1-3 proteins confirmed the predicted molecular weights of 47.6, 42.3 and 46.5 kDa, respectively (Figure 5A). The purified AtRIBA proteins were assayed for GCHII and DHBPS activity in vitro (Figure 5B,C). A GCHII enzymatic function was clearly demonstrated for RIBA1 as well as for RIBA3, whereas RIBA2 did not display a detectable activity (Figure 5B). A DHBPS activity was determined for RIBA1 and RIBA2. Here, RIBA3 did not display a measurable DHBPS enzymatic function (Figure 5C). Taken together, the data obtained from in vitro assays clearly indicate that both recombinant AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3 isoforms are able to carry out only one of two enzymatic activities of bifunctional RIBA proteins.

Figure 5.

Enzymatic activities of AtRIBA proteins. (A–C) His-tagged N-terminally truncated AtRIBA proteins were overexpressed in E. coli and purified by FPLC. (A) Coomassie staining following SDS PAGE detects highly enriched recombinant Arabidopsis proteins in selected FPLC fractions. 0.75 μg of each recombinant RIBA protein were applied. The obtained fractions were assayed in vitro for enzymatic activity for GCHII (B) and DHBPS (C). In both assays a standard RIBA protein (RibA from Bacillus subtilis) was included as positive control. (D,E) E. coli ribA (D) and ribB (E) mutants were transformed with plasmids encoding the three Arabidopsis RIBA isoforms. Growth (OD600) of at least three independent cultures in liquid M9 minimal medium was monitored for 24 h; the initial absorption of the culture was subtracted. Empty vector pACYC184 was used as negative control; the maximum density reached by the control did not exceed an OD600 of 0.2 (grey line). Standard errors are indicated.

2.5. Complementation of Bacterial Mutants

In E. coli, ribA and ribB genes encode monofunctional GCHII and DHBPS enzymes, respectively. Corresponding E. coli mutant strains were employed to study complementation of respective enzymatic functions by RIBA1-3 in situ and corroborate the data obtained in vitro.

AtRIBA sequences designed for expression in E. coli (Data S1) were cloned into pACYC184 and transformed into E. coli ribA and ribB mutants, respectively. The vector pACYC184 was also used as blank control. We assayed the growth rate (OD600) of resulting E. coli transformants in M9 minimal medium liquid cultures (Figure 5D,E). Since ribA and ribB are riboflavin auxotrophs, precultures were grown in LB medium containing 0.4 g/L riboflavin. At OD600 of 0.6, the cells were pelleted, washed and resuspended in M9 minimal medium (OD600 = 0.1) and grown at 37 °C for 24 h.

Cultures of both E. coli mutants containing plasmid pACYC184 reached in M9 minimal medium a stationary phase at OD600 of approx. 0.2 (Figure 5D,E). Cultures of the ribA mutant (deficiency in GCHII) revealed an enhanced growth rate when transformed with RIBA1 or RIBA3 constructs, while the growth rate of E. coli ribA cells transformed with pACYC-AtRIBA2 did not differ from the blank control strain (Figure 5D). The culture of the DHBPS-deficient mutant strain ribB displayed an enhanced growth when transformed with either the RIBA1 or RIBA2 encoding plasmid. In contrast, pACYC-AtRIBA3 was not able to improve the growth rate in comparison to the empty control plasmid (Figure 5E).

3. Discussion

3.1. Consequences of AtRIBA1 Deficiency in Arabidopsis

Based on the description of rfd1[17,18], the specific function of the three homologous AtRIBA genes in Arabidopsis riboflavin biosynthesis was further investigated. Transgenic lines were generated that constitutively express AtRIBA1 antisense RNA. These new lines displayed various degrees of a bleaching leaf phenotype (Figure 3A) occurring at different stages of plant development. An early bleaching of individual lines, like A1#2, phenotypically resembled rfd1. These lines were unable to survive under photoautotrophic conditions. The leaves of other transgenic lines including A1#5 bleached later during plant development (Figure 3A). Here, the first leaves developed with wild-type like pigmentation, while new leaves in the Arabidopsis rosette stage turned white. The loss of pigmentation corresponds to inactivation of AtRIBA1 expression as demonstrated by quantitative PCR analysis (Figures 2B and 3D).

Numerous Arabidopsis tissues were analyzed by qPCR to compare the abundance of AtRIBA mRNAs. The transcript profile of all three homologous RIBA genes (Figure 2A) reveals a largely constitutive expression with AtRIBA1 being the most abundant transcript in all tested tissues. This implies that AtRIBA2 as well as AtRIBA3 are ubiquitously expressed and their expression has at least the potential to partially complement AtRIBA1 deficiency. The transcript analysis of antisense lines (Figure 2B), however, demonstrates that there is no concerted transcriptional regulation of the RIBA gene family members in Arabidopsis, since the isogenes did not show altered transcript accumulation in AtRIBA1 antisense lines.

It could be speculated that the characteristic bleaching phenotype is explained by an insufficient dosage of expressed RIBA protein as the overall amount of RIBA transcripts and proteins in antisense plants is severely reduced (Figures 2B and 3C,D). Alternatively, the lack of complementation of AtRIBA1 deficiency might be caused by differences in subcellular localization or enzymatic functions among the homologs.

The localization of the RIBA isoforms was tested employing GFP fusions in transiently transformed Nicotiana leaf cells. All three AtRIBA proteins possess N-terminal sequences that exclusively direct GFP fusions to plastids (Figure 4). These findings agree with mass spectrometry data available for all three proteins from plastid proteome projects as summarized in the SubCellular Proteomic Database (SUBA, http://suba.plantenergy.uwa.edu.au/) [22] as well with data available for further enzymes of riboflavin synthesis (SUBA entries for At4g20960, At2g44050, At2g20690) and, thus, corroborates the assumption that plant riboflavin biosynthesis is exclusively localized in plastids [9]. In conclusion, the plastid localization of all three RIBA isoforms does not explain the inability of RIBA2 and RIBA3 to complement RIBA1 deficiency in Arabidopsis.

Differences in enzymatic activities of the bifunctional A. thaliana RIBA homologs have previously been suggested when the protein primary structures were compared with sequences of bacterial RibA proteins (Figure S1 in [17]). Amino acids known to be indispensable for either binding of zinc ions (i.e. for GCHII activity) or substrate binding and catalysis (i.e., for DHBPS activity) are lacking in AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3, respectively [23,24]. The recent characterization of a N. benthamiana RIBA homolog underlined the functional importance of specific residues in plant RIBA sequences [25].

3.2. Analyses of Enzymatic Activities of AtRIBA Isoforms

The present work aimed at comparatively examining the enzymatic activities of all three AtRIBA homologs by two alternative approaches. First, purified recombinant RIBA proteins were employed in in vitro assays (Figure 5A–C). Second, the complementation of E. coli ribA and ribB mutants substantiated the results in situ (Figure 5D,E). A ribB (DHBPS)-deficient strain showed improved growth characteristics when complemented with the AtRIBA1 and AtRIBA2 sequences. Although the complementation was only partial, the elevated growth rate was characteristic in comparison to that of the same mutant containing the AtRIBA3-expressing plasmid. The complementation of ribA deficient E. coli cells was more effective by AtRIBA1 than by AtRIBA3. However, the latter exceeded the effect of AtRIBA2 and the pACYC184 vector control.

In conclusion, both the in vitro and the in situ approaches confirmed the hypothesis that AtRIBA2 as well as AtRIBA3 represent only mono- instead of bifunctional enzymes for riboflavin biosynthesis: while AtRIBA2 is lacking GCHII activity, AtRIBA3 does not display DHBPS function.

3.3. RIBA Genes Lacking DHBPS Activity Evolved Early in Vascular Plant Phylogeny

The architecture of bifunctional enzymes has been suggested to favor the coordination of expression and catalysis [26]. GCHII and DHBPS are the first committed enzymes of a converged pathway, in which two molecules of the DHBPS product and one of GCHII (9 and 2 in Figure 1) are required to finally synthesize riboflavin. Interestingly, in vitro enzyme assays revealed a two times higher activity of recombinant DHBPS compared to GCHII [10]. Hence, the expression of a fused DHBPS-GCHII protein could ensure catalysis of adequate amounts of reaction products required in the riboflavin biosynthetic pathway [26].

We make the point that the Arabidopsis genome contains two genes encoding bipartite proteins with only one enzymatic function in the riboflavin biosynthetic pathway. We assert, with our results, that expression of both monofunctional enzymes is insufficient for a replacement of bifunctional AtRIBA1. Different reasons may account for the lack of complementation by means of AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3: their lower expression strength in comparison to AtRIBA1, steric hindrance of the two monofunctional proteins or an involvement of the latter in other metabolic pathways.

In addition, we can not entirely exclude potential mechanistic and structural functions of RIBA2 and RIBA3 in the formation of multienzymatic complexes in riboflavin biosynthesis. Thus, sequestration and protection of labile metabolic intermediates can improve metabolic channeling as demonstrated recently for bifunctional BIO3-BIO1 in Arabidopsis biotin synthesis [27].

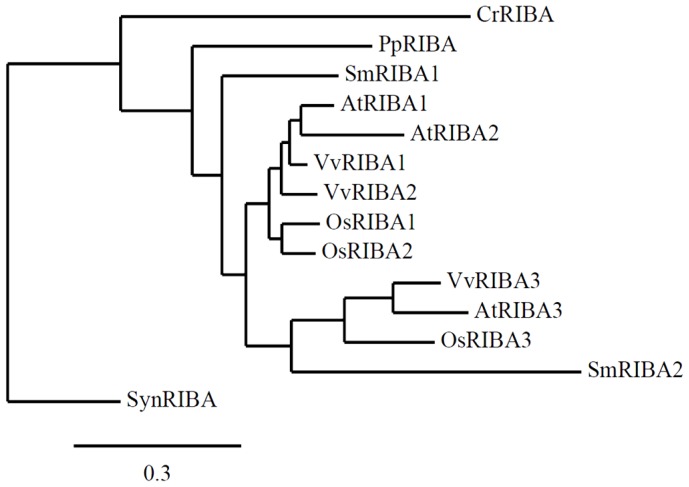

Interestingly, the occurrence of at least three RIBA homologs is conserved among all angiosperms of which complete genome data are available. The sequence similarity of the different isoforms was investigated by phylogenetic analysis (Figure 6). As indicated, Selaginella, an early tracheophyte, represents the first plant harboring more than one RIBA gene. Already one of the two isoforms found in the genome of this lycopodiophyte (designated SmRIBA2 in Figure 6) is situated in a RIBA3-specific clade of the phylogenetic tree. A comparison of protein primary sequences reveals an exchange of essential amino acids in all members of this RIBA3 clade and thus implies a loss of DHBPS function in this group early in higher plant evolution (Figure S1). This hints at a specific requirement for an independent GCHII activity that became irreplaceable due to an acquisition of special functions in plant metabolism. Interestingly, evolutionary changes of GCHII activities have been reported recently for three GCHII isogenes in Streptomyces[28].

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree of selected plant RIBA protein sequences. RIBA gene families identified in the angiosperm species Arabidopsis thaliana (At), Vitis vinifera (Vv) and Oryza sativa (Os), two RIBA proteins from a lycopodiophyte species (Selaginella, Sm), as well as single RIBA sequences from a moss (Physcomitrella, Pp), a green algae (Chlamydomonas, Cr), and a cyanobacterium (Synechococcus, Syn) are included in the analysis. Alignment (using MUSCLE 3.7 and Gblocks 0.91b), phylogenetic analysis (PhyML3.0 aLRT) and tree rendering (TreeDyn 198.3) were performed using the phylogeny resource (http://www.phylogeny.fr) [29], the tree was re-rooted using SynRIBA as outgroup. Full length RIBA amino acid sequences of the following species were used: Arabidopsis thaliana (accession nrs. NP_201235, NP_179831, NP_568913), Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (XP_001689850), Oryza sativa (NP_001047195, BAD09287, NP_001055757), Physcomitrella patens (XP_001770447), Selaginella moellendorfii (XP_002962016, XP_002960875), Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 (YP_001733693), Vitis vinifera (XP_002267374, XP_002266093, XP_002281446).

It is noteworthy that Arabidopsis possesses an unusual set of RIBA isoforms with AtRIBA2 being monofunctional in riboflavin biosynthesis. All other inspected angiosperm species comprise RIBA2 genes that encode all necessary amino acids to fulfill DHBPS as well as GCHII function as illustrated by the amino acid alignment depicted in Figure S2. Due to the close relationship of RIBA1 and RIBA2 isoforms they are forming a common clade in the phylogenetic tree. However, the unusual evolutionary situation of AtRIBA2 is reflected by an extended branch length (Figure 6).

At present, we hypothesize that the loss of bifunctionality for two out of three AtRIBA isoforms hints either at novel metabolic functions or at a structural role in the spatial organization of plant riboflavin biosynthesis. To investigate the specific impact of a loss of AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3 function on plant metabolism is hence a challenging task to be addressed in the future.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Generation of Antisense Lines

The AtRIBA1 coding region was amplified using primers 17 and 18 (Table S1). The product was cut using SmaI and inserted into binary vector pGL1, which was derived from pGPTV-bar [30] by removing GUS and introducing a 35S CaMV promoter and a multiple cloning site. A. thaliana was transformed using standard procedures.

4.2. Heterologous Overexpression

Enzymatically essential RIBA regions were identified based on alignments with prokaryotic RibA and RibB ([17], therein Figure S1). Arabidopsis sequences were adapted to E. coli codon usage and N-terminal His-tags integrated (Data S1). Sequences were provided as pUC57 subclones by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA). NdeI/HindIII fragments were cloned into pET22b(+) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Expression in ArcticExpress™ (DE3) RIL Competent Cells (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was induced with 1 mM IPTG at 13 °C for 24 h. Soluble recombinant proteins were purified via FPLC using HisTrap HP columns (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) and dialyzed with SnakeSkinTM Pleated Dialysis Tubing (10,000 MWCO, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, pH 8.4. The concentration of recombinant RIBA protein fractions was determined by comparison to Bovine Serum Albumin standards on Coomassie stained gels.

4.3. Assays of GCHII and DHBPS Activity

The enzyme assays were performed according to [31] with minor modifications. For GCHII activity: Assay mixtures (100 μL) containing 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 100 μM GTP and either RibA from B. subtilis (0.5 mg/mL) or RIBA1-3 from A. thaliana (0.975, 0.15, 0.175 μg/μL) were incubated 1 h at 37 °C. After addition of EDTA (10 mM) and diacetyl (5 mM), the samples were incubated 1 h at 37 °C. Then, 100 μL of TCA (300 mM) were added and samples centrifuged for 2 min at 13,000 rpm and 10 °C. 20 μL from the supernatant were loaded on RP18 column (Lichrospher100 RP18, 5 μL, 250 × 4 mm, flow rate 1 mL min−1) and eluted isocratically with methanol/water (v/v 4:6). Effluent fluorescence of 6,7-dimethylpterin was monitored (λex 340 nm; λem 400 nm). For DHBPS activity: assay mixtures (100 μL) containing 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 100 μM d-ribose 5-phosphate, phosphoriboisomerase (0.5 U/mL), 100 μM, 5-diamino-6-ribitylamino-2,4(1H,3H) pyrimidinedione, lumazine synthase of B. subtilis (0.5 U/mL) and either B. subtilis RibA (0.5 mg/mL) or A. thaliana RIBA1-3 (0.975, 0.15, 0.175 μg/μL) were incubated 2 h at 37 °C. 20 μL from the supernatant were loaded on RP18 column and eluted isocratically with methanol/water/formic acid (26:234:1). Effluent fluorescence of 6,7-dimethyl-8- ribityllumazine was monitored (λex 408 nm; λem 490 nm). Synthetic dimethylpterin and 6,7-dimethyl- 8-ribityllumazine have been used as calibration standards.

4.4. Complementation Assays

RIBA1 and RIBA3 sequences were cut from pUC57 (see above) with Ecl136II/HincII (RIBA1) or Ecl136II/SmaI (RIBA3). For RIBA2, primers 1 and 2 (Table S1) were applied using RIBA2 in pUC57 as template; the resulting product was cut with PsiI. All RIBA fragments were inserted into the EcoRV site of pACYC184 (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA). Constructs were transformed into E. coli knock-out strains BSV18 (ribA18::Tn5; CGSC# 6992) and BSV11 (ribB11::Tn5; CGSC# 6991) defective in RibA (GCHII) and RibB (DHBPS), respectively, [32] obtained from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center (http://cgsc.biology.yale.edu/).

For growth assays, LB cultures with 0.4 g/L riboflavin were inoculated with an overnight culture and grown at 37 °C, 250 rpm to an OD600 of 0.6. The mutants require high concentrations of externally added flavins due to the lack of specific riboflavin import mechanisms in E. coli. Cells were pelleted and washed three times in M9 minimal medium containing 20% glucose [33]. M9 cultures containing antibiotics were inoculated with washed cells to give an initial OD600 of 0.1.

4.5. RNA Isolation and Quantification

Total RNA was isolated using innuPREP Plant RNA Kit (Analytic Jena, Jena, Germany). 0.4 μg of DNAseI-pretreated total RNA was reverse transcribed with oligo dT18 using RevertAid RT (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). cDNA was amplified with SensiMix SYBR No-ROX kit (Bioline, London, UK) on a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using the oligonucleotides listed in Table S1. Expression rates were calculated relative to SAND (At2g28390 [34]) according to the 2−ΔCT method [35,36].

4.6. HPLC Analysis

Plant material (0.1 g) harvested from rosette leaves of 8-week-old plants grown under short day conditions (10 h light/14 h dark) at 120 μmole photons m−2 s−1 was ground in liquid N2, resuspended in 0.5 mL of methanol/methylen chloride (9:10), incubated for 2 h under gentle agitation at 4 °C and centrifuged. Samples were analyzed on HPLC system 1100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using a NovaPak C18 column (150 mm; 3.9 mm diameter; 4 μm particle size) and eluted with a linear gradient of 50 mM ammonium acetate (pH 6) and methanol from 100% to 47% over 20 min at 0.8 mL/min. Riboflavin, FMN and FAD were detected by fluorescence (λex 265 nm, λem 530 nm) and confirmed using authentic standards (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

4.7. Subcellular Localization of RIBA-GFP Fusions

N-termini of RIBA proteins were amplified from cDNA using primers 3/4, 5/6 and 7/8 (Table S1). Products were cut by SmaI (RIBA1) or KpnI/SmaI (RIBA2, RIBA3) restrictions and ligated into modified pCF203. [37] Resulting plasmids were transformed into A. tumefaciens pGV2260 and used to infiltrate Nicotiana benthamiana leaves [38]. Transient GFP expression was visualized by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) (λex 488 nm, GFP λem 500–550 nm, chlorophyll λem 600–700nm).

4.8. Protein Analysis

Proteins were separated on 12% polyacrylamide gels as described [39]. Immune-detection of AtRIBA used a polyclonal anti-RIBA1 antiserum (Biogenes, Berlin, Germany) which was affinity-purified on nitrocellulose-bound antigen. Immune-detection used HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), ECL Western Blotting Detection System (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) and a Stella 3200 (raytest Isotopenmessgeräte GmbH, Straubenhardt, Germany).

5. Conclusions

Converged riboflavin biosynthesis starts with GTP cyclohydrolase II (GCHII) and 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase (DHBPS). Three genes, AtRIBA1, AtRIBA2 and AtRIBA3 encode the putatively bifunctional RIBA protein with both catalytic properties in Arabidopsis. However, two out of three members of the Arabidopsis gene family encode the bipartite RIBA protein, but show only one of the two enzymatic functions required for riboflavin biosynthesis. Thus, AtRIBA3 possesses only a GCHII function, while only AtRIBA2 possesses the DHBPS activity. Interestingly, a phenotypical analysis of an Arabidopsis ribA1 mutant revealed that the two monofunctional RIBA2 and 3 do not compensate for RIBA1 deficiency in planta.

Supplementary Information

Comparison of RIBA3 clade members. Partial alignments of RIBA3 clade members with bifunctional AtRIBA1 (underlined). Enzymatically important amino acid residues for DHBPS (A) and GCHII (B) function are highlighted in yellow. Substitutions in catalytic or substrate binding domains of the different RIBA3 sequences are marked in red. The loss of essential amino acids is restricted to DHBPS regions. This classifies all members of the RIBA3 clade as monofunctional enzymes possessing GTP cyclohydrolase II activity only. Important residues and domains for both enzymes have been identified previously [40–43]. MULTALIN (http://multalin.toulouse.inra.fr/multalin/) [44] and GeneDoc (http://www.nrbsc.org/gfx/genedoc) [45] were used to generate and edit alignments. Amino acid numbers are indicated at the right margin. At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Vv, Vitis vinifera; Os, Oryza sativa; Sm, Selaginella moellendorfii.

Alignment of RIBA1 and RIBA2 isoforms. Sequence comparison of higher plant RIBA1 and RIBA2 (bold) proteins with bifunctional AtRIBA1 (underlined). Enzymatically important amino acid residues for DHBPS (A) and GCHII (B) function are highlighted in yellow. Deviations in zinc binding residues as well as a C-terminal deletion uniquely present in AtRIBA2 are marked in red. The loss of essential amino acids is restricted to the GCHII part of AtRIBA2, qualifying all other RIBA2 isoforms as truly bifunctional proteins.

Sequences of synthetic genes AtRIBA1-3. Nucleotide sequences have been modified by avoiding rare codons known to impede expression in E. coli and by introduction of unique restriction sites. N-terminally a sixfold His motif and an enterokinase cleavage site were added (underlined), restriction sites at the 5′- and 3′-termini are shown in italics. The derived primary protein sequences starting at amino acid 127 (AtRIBA1), 105 (AtRIBA2) and 100 (AtRIBA3), respectively, of the precursor proteins were not altered by the introduced nucleotide changes.

Table S1.

List of used Primers.

| Nr. | Designation | Sequence 5′→3′ |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | RibA2_PsiI_fw | AATTATAACAGTCGACGGGCCCG |

| 2 | RibA2_PsiI_rev | GCTTATAATACCTCGCGAATGCATCT |

| 3 | RibA1_GFP_fw | ACCCGGGACAATGTCTTCCATCAATTTATCC |

| 4 | RibA1_GFP_rev | ACCCGGGATCTTCTCTAGAGATCACTGCAG |

| 5 | RibA2_GFP_fw | CAGGTACCAAAATGGCGTCGCTTACT |

| 6 | RibA2_GFP_rev | ACCCGGGTTCAGGAGAATCCATTGTTG |

| 7 | RibA3_GFP_fw | CAGGTACCACGATGATGGATTCTGCTTTA |

| 8 | RibA3_GFP_rev | ACCCGGGATCAAACAACGACCCGTC |

| 9 | qRT_At5g64300_fw2 | TTGTTACTTCTTGTTGTCGGG |

| 10 | qRT_At5g64300_rev2 | TGATGATCCACATTCCACAC |

| 11 | qRT_At2g22450_fw2 | GGTTCCACTCATTACTACTCCT |

| 12 | qRT_At2g22450_rev2 | AAACTAAGTCACTCAAGAAGCC |

| 13 | qRT_At5g59750_fw1 | AGACTAATGACGAATAACCCTG |

| 14 | qRT_At5g59750_rev1 | ATATCTTCTGTTCTCCTTGGTG |

| 15 | qRT_SAND_fw | AACTCTATGCAGCATTTGATCCACT |

| 16 | qRT_SAND_rev | TGATTGCATATCTTTATCGCCATC |

| 17 | AtRIBA1fw | ACCCGGGACAATGTCTTCCATCAATTTATCC |

| 18 | AtRIBA1rev | ACCCGGGTCAGGACTCAGATTCAGACTCAATC |

Abbreviations

- CLSM

confocal laser scanning microscopy

- DHBPS

3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4- phosphate synthase

- GCHII

GTP cyclohydrolase II

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

References

- 1.Bacher A., Eberhardt S., Fischer M., Kis K., Richter G. Biosynthesis of vitamin b2 (riboflavin) Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2000;20:153–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischer M., Bacher A. Biosynthesis of vitamin B2: Structure and mechanism of riboflavin synthase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008;474:252–265. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouyang M., Ma J., Zou M., Guo J., Wang L., Lu C., Zhang L. The photosensitive phs1 mutant is impaired in the riboflavin biogenesis pathway. J. Plant. Physiol. 2010;167:1466–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bacher A., Eberhardt S., Eisenreich W., Fischer M., Herz S., Illarionov B., Kis K., Richter G. Biosynthesis of riboflavin. Vitam. Horm. 2001;61:1–49. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(01)61001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitsuda H., Suzuki Y., Kawai F. Biogenesis of Riboflavin in Green Leaves. Vi. Non-Enzymatic Production of 6-Methyl-7-Hydroxy-8-Ribityllumazine from New Organic Reaction of 6,7-Dimethyl-8-Ribityllumazine with P-Quinone. J. Vitaminol. (Kyoto) 1963;66:125–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitsuda H., Kawai F., Suzuki Y., Yoshimoto S. Biogenesis of riboflavin in green leaves. VII. Isolation and characterization of spinach riboflavin synthetase. J. Vitaminol. (Kyoto) 1970;16:285–292. doi: 10.5925/jnsv1954.16.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatwell L., Krojer T., Fidler A., Romisch W., Eisenreich W., Bacher A., Huber R., Fischer M. Biosynthesis of riboflavin: structure and properties of 2,5-diamino-6-ribosylamino- 4(3H)-pyrimidinone 5′-phosphate reductase of Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;359:1334–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer M., Haase I., Feicht R., Schramek N., Kohler P., Schieberle P., Bacher A. Evolution of vitamin B2 biosynthesis: riboflavin synthase of Arabidopsis thaliana and its inhibition by riboflavin. Biol. Chem. 2005;386:417–428. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer M., Romisch W., Saller S., Illarionov B., Richter G., Rohdich F., Eisenreich W., Bacher A. Evolution of vitamin B2 biosynthesis: Structural and functional similarity between pyrimidine deaminases of eubacterial and plant origin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:36299–36308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herz S., Eberhardt S., Bacher A. Biosynthesis of riboflavin in plants. The ribA gene of Arabidopsis thaliana specifies a bifunctional GTP cyclohydrolase II/3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone 4-phosphate synthase. Phytochemistry. 2000;53:723–731. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan D.B., Bacot K.O., Carlson T.J., Kessel M., Viitanen P.V. Plant riboflavin biosynthesis. Cloning, chloroplast localization, expression, purification, and partial characterization of spinach lumazine synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:22114–22121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.22114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giancaspero T.A., Locato V., de Pinto M.C., de Gara L., Barile M. The occurrence of riboflavin kinase and FAD synthetase ensures FAD synthesis in tobacco mitochondria and maintenance of cellular redox status. FEBS J. 2009;276:219–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandoval F.J., Roje S. An FMN hydrolase is fused to a riboflavin kinase homolog in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:38337–38345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500350200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandoval F.J., Zhang Y., Roje S. Flavin nucleotide metabolism in plants: Monofunctional enzymes synthesize fad in plastids. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:30890–30900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803416200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richter G., Ritz H., Katzenmeier G., Volk R., Kohnle A., Lottspeich F., Allendorf D., Bacher A. Biosynthesis of riboflavin: Cloning, sequencing, mapping, and expression of the gene coding for GTP cyclohydrolase II in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:4045–4051. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.4045-4051.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richter G., Volk R., Krieger C., Lahm H.W., Rothlisberger U., Bacher A. Biosynthesis of riboflavin: Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the gene coding for 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone 4-phosphate synthase of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:4050–4056. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.4050-4056.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedtke B., Alawady A., Albacete A., Kobayashi K., Melzer M., Roitsch T., Masuda T., Grimm B. Deficiency in riboflavin biosynthesis affects tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in etiolated Arabidopsis tissue. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012;78:77–93. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedtke B., Grimm B. Silencing of a plant gene by transcriptional interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3739–3746. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bannai H., Tamada Y., Maruyama O., Nakai K., Miyano S. Extensive feature detection of N-terminal protein sorting signals. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:298–305. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.2.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emanuelsson O., Nielsen H., Brunak S., von Heijne G. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins based on their N-terminal amino acid sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;300:1005–1016. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Predotar 1.03—A Prediction Service for Identifying Putative N-Terminal Targeting Sequences. [accessed on 19 February 2012]. Available online: http://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/predotar/predotar.html.

- 22.Heazlewood J.L., Verboom R.E., Tonti-Filippini J., Small I., Millar A.H. SUBA: The Arabidopsis Subcellular Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D213–D218. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer M., Romisch W., Schiffmann S., Kelly M., Oschkinat H., Steinbacher S., Huber R., Eisenreich W., Richter G., Bacher A. Biosynthesis of riboflavin in archaea studies on the mechanism of 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase of Methanococcus jannaschii. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:41410–41416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206863200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser J., Schramek N., Eberhardt S., Puttmer S., Schuster M., Bacher A. Biosynthesis of vitamin B2. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:5264–5270. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asai S., Mase K., Yoshioka H. A key enzyme for flavin synthesis is required for nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species production in disease resistance. Plant J. 2010;62:911–924. doi: 10.1111/j.0960-7412.2010.04206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore B. Bifunctional and moonlighting enzymes: Lighting the way to regulatory control. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cobessi D., Dumas R., Pautre V., Meinguet C., Ferrer J.L., Alban C. Biochemical and structural characterization of the Arabidopsis bifunctional enzyme dethiobiotin synthetase-diaminopelargonic acid aminotransferase: Evidence for substrate channeling in biotin synthesis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1608–1625. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.097675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spoonamore J.E., Dahlgran A.L., Jacobsen N.E., Bandarian V. Evolution of new function in the GTP cyclohydrolase II proteins of Streptomyces coelicolor. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12144–12155. doi: 10.1021/bi061005x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dereeper A., Guignon V., Blanc G., Audic S., Buffet S., Chevenet F., Dufayard J.F., Guindon S., Lefort V., Lescot M., et al. Phylogeny.fr: Robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W465–W469. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Becker D., Kemper E., Schell J., Masterson R. New plant binary vectors with selectable markers located proximal to the left T-DNA border. Plant Mol. Biol. 1992;20:1195–1197. doi: 10.1007/BF00028908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bacher A., Richter G., Ritz H., Eberhardt S., Fischer M., Krieger C. Biosynthesis of riboflavin: GTP cyclohydrolase II, deaminase, and reductase. Methods Enzymol. 1997;280:382–389. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)80129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bandrin S.V., Rabinovich P.M., Stepanov A.I. 3 linkage groups of the genes of riboflavin biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Genetika. 1983;19:1419–1425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J., Russell D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czechowski T., Bari R.P., Stitt M., Scheible W.R., Udvardi M.K. Real-time RT-PCR profiling of over 1400 Arabidopsis transcription factors: Unprecedented sensitivity reveals novel root- and shoot-specific genes. Plant J. 2004;38:366–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmittgen T.D., Livak K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chincinska I.A., Liesche J., Krugel U., Michalska J., Geigenberger P., Grimm B., Kuhn C. Sucrose transporter StSUT4 from potato affects flowering, tuberization, and shade avoidance response. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:515–528. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.112334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bendahmane A., Querci M., Kanyuka K., Baulcombe D.C. Agrobacterium transient expression system as a tool for the isolation of disease resistance genes: Application to the Rx2 locus in potato. Plant J. 2000;21:73–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laemmli U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischer M., Romisch W., Schiffmann S., Kelly M., Oschkinat H., Steinbacher S., Huber R., Eisenreich W., Richter G., Bacher A. Biosynthesis of riboflavin in archaea studies on the mechanism of 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase of Methanococcus jannaschii. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:41410–41416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206863200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaiser J., Schramek N., Eberhardt S., Puttmer S., Schuster M., Bacher A. Biosynthesis of vitamin B2. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:5264–5270. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinbacher S., Schiffmann S., Richter G., Huber R., Bacher A., Fischer M. Structure of 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone 4-phosphate synthase from Methanococcus jannaschii in complex with divalent metal ions and the substrate ribulose 5-phosphate: implications for the catalytic mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:42256–42265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307301200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ren J., Kotaka M., Lockyer M., Lamb H.K., Hawkins A.R., Stammers D.K. GTP Cyclohydrolase II Structure and Mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:36912–36919. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507725200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucl. Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicholas K.B., Nicholas H.B., Jr, Deerfield D.W., II GeneDoc: Analysis and Visualization of Genetic Variation. EMBnet News. 1997;4:14. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Comparison of RIBA3 clade members. Partial alignments of RIBA3 clade members with bifunctional AtRIBA1 (underlined). Enzymatically important amino acid residues for DHBPS (A) and GCHII (B) function are highlighted in yellow. Substitutions in catalytic or substrate binding domains of the different RIBA3 sequences are marked in red. The loss of essential amino acids is restricted to DHBPS regions. This classifies all members of the RIBA3 clade as monofunctional enzymes possessing GTP cyclohydrolase II activity only. Important residues and domains for both enzymes have been identified previously [40–43]. MULTALIN (http://multalin.toulouse.inra.fr/multalin/) [44] and GeneDoc (http://www.nrbsc.org/gfx/genedoc) [45] were used to generate and edit alignments. Amino acid numbers are indicated at the right margin. At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Vv, Vitis vinifera; Os, Oryza sativa; Sm, Selaginella moellendorfii.

Alignment of RIBA1 and RIBA2 isoforms. Sequence comparison of higher plant RIBA1 and RIBA2 (bold) proteins with bifunctional AtRIBA1 (underlined). Enzymatically important amino acid residues for DHBPS (A) and GCHII (B) function are highlighted in yellow. Deviations in zinc binding residues as well as a C-terminal deletion uniquely present in AtRIBA2 are marked in red. The loss of essential amino acids is restricted to the GCHII part of AtRIBA2, qualifying all other RIBA2 isoforms as truly bifunctional proteins.

Sequences of synthetic genes AtRIBA1-3. Nucleotide sequences have been modified by avoiding rare codons known to impede expression in E. coli and by introduction of unique restriction sites. N-terminally a sixfold His motif and an enterokinase cleavage site were added (underlined), restriction sites at the 5′- and 3′-termini are shown in italics. The derived primary protein sequences starting at amino acid 127 (AtRIBA1), 105 (AtRIBA2) and 100 (AtRIBA3), respectively, of the precursor proteins were not altered by the introduced nucleotide changes.

Table S1.

List of used Primers.

| Nr. | Designation | Sequence 5′→3′ |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | RibA2_PsiI_fw | AATTATAACAGTCGACGGGCCCG |

| 2 | RibA2_PsiI_rev | GCTTATAATACCTCGCGAATGCATCT |

| 3 | RibA1_GFP_fw | ACCCGGGACAATGTCTTCCATCAATTTATCC |

| 4 | RibA1_GFP_rev | ACCCGGGATCTTCTCTAGAGATCACTGCAG |

| 5 | RibA2_GFP_fw | CAGGTACCAAAATGGCGTCGCTTACT |

| 6 | RibA2_GFP_rev | ACCCGGGTTCAGGAGAATCCATTGTTG |

| 7 | RibA3_GFP_fw | CAGGTACCACGATGATGGATTCTGCTTTA |

| 8 | RibA3_GFP_rev | ACCCGGGATCAAACAACGACCCGTC |

| 9 | qRT_At5g64300_fw2 | TTGTTACTTCTTGTTGTCGGG |

| 10 | qRT_At5g64300_rev2 | TGATGATCCACATTCCACAC |

| 11 | qRT_At2g22450_fw2 | GGTTCCACTCATTACTACTCCT |

| 12 | qRT_At2g22450_rev2 | AAACTAAGTCACTCAAGAAGCC |

| 13 | qRT_At5g59750_fw1 | AGACTAATGACGAATAACCCTG |

| 14 | qRT_At5g59750_rev1 | ATATCTTCTGTTCTCCTTGGTG |

| 15 | qRT_SAND_fw | AACTCTATGCAGCATTTGATCCACT |

| 16 | qRT_SAND_rev | TGATTGCATATCTTTATCGCCATC |

| 17 | AtRIBA1fw | ACCCGGGACAATGTCTTCCATCAATTTATCC |

| 18 | AtRIBA1rev | ACCCGGGTCAGGACTCAGATTCAGACTCAATC |