Abstract

Over 20.000 umblical cord blood transplantations (UCBT) have been carried out around the world. Indeed, UCBT represents an attractive source of donor hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and, offer interesting features (e.g., lower graft-versus-host disease) compared to bone marrow transplantation (BMT). Thereby, UCBT often represents the unique curative option against several blood diseases. Recent advances in the field of UCBT, consisted to develop strategies to expand umbilical stem cells and shorter the timing of their engraftment, subsequently enhancing their availability for enhanced efficacy of transplantation into indicated patients with malignant diseases (e.g., leukemia) or non-malignant diseases (e.g., thalassemia major). Several studies showed that the expansion and homing of UCBSCs depends on specific biological factors and cell types (e.g., cytokines, neuropeptides, co-culture with stromal cells). In this review, we extensively present the advantages and disadvantages of current hematopoietic stem cell transplantations (HSCTs), compared to UBCT. We further describe the importance of cord blood content and obstetric factors on cord blood selection, and report the recent approaches that can be undertook to improve cord blood stem cell expansion as well as engraftment. Eventually, we provide two majors examples underlining the importance of UCBT as a potential cure for blood diseases.

1. Introduction

Umbilical cord blood (UCB) availability as a prospect for therapeutic use was first reported in the British journal, Lancet, in 1939 [1]. The proposed use was transfusional, but outside of the neonatology clinic, the concept was slow to be accepted, with standard adult blood transfusions being more available. Many years passed before E. Donnall Thomas eventually achieved bone marrow transplantation (BMT) in the 1950s, leading to his later Nobel Prize. Along with this clinical milestone, became a slow but growing awareness that UCB might also be of interest, but it was not until the 1970s when the medical brothers Ende published the transplantation of multiple units of UCB into an individual [2]. Sadly, this procedure was not successful, most likely because of the complications related to the multiple immunology disparities of the transplant units. However, the procedure did start a new move to investigate cord blood on a more serious level.

Eventually, in 1988, successful transplant for bone marrow replacement of a sibling with Fanconi's anaemia was achieved and then published in 1989 [3]. The growth of this possibility to use what is one of the largest cellular sources available on the planet, but normally discarded, was an exciting move which has now led to UCB being considered an attractive alternative source of donor hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the treatment of both recurrent or refractory malignant hematologic disorders (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma) and nonmalignant blood diseases (e.g., thalassemia, sickle cell disease) [4–6]. Indeed, since its successful initial use in 1988, umbillical cord blood transplantation (UCBT), particularly allogeneic-UCBT, from both related and unrelated donors, is increasingly used worldwide to treat patients, mostly pediatrics, with either malignant or nonmalignant disorders [3, 7–9]. To date, over 20.000 transplantation procedures have been performed from unrelated donor UCB units, and more than 450.000 UCB units have been collected and banked by approximately 50 public cord blood banks worldwide [4, 10–12].

Globally, UBCT presents the following advantages over BMT [4, 11–14]: (i) lower incidence and lower severity of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), a leading cause of morbidity and mortality; (ii) possibility of extending the number of HLA-antigen mismatches to 1 to 2 of the 6 HLA loci currently considered in UCB transplantation; (iii) lower risk of transmitting latent virus infections (e.g., cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis viruses, human immunodeficiency virus); (iv) elimination of clinical risk to the donor during hematopoietic stem cell procurement procedures; (v) higher frequency of rare HLA haplotype representation in the donor pool; (vi) a rapid tempo of immune reconstitution. However, these advantages are balanced by two main disadvantages compared to BMT [4, 11–13, 15]: (i) higher risk of graft rejection because of possible translation of the naive immune system into a blunted allogeneic effect elicited by donor T lymphocytes (i.e., immunologic barriers to engraftment); (ii) delayed hematopoietic recovery after transplantation, due to a reduced number of hematopoietic progenitor cells that can further contribute to serious infections.

Interestingly, children with nonmalignant disorders experienced a higher rate of graft rejection after UBCT compared with children suffering from a malignant disorder [16–18]. The reason(s) of such difference might be linked to [8, 19–23]: (i) the T-cell depletion, (ii) the total nucleated cell (TNC) dose along with the colony-forming unit (CFU) activity and CD34+ cells (HSC) which has a profound impact on engraftment, transplant-related complications (infection risk, survival), (iii) the degree of HLA mismatching (i.e., recipients who had greater than 2 HLA mismatches, assessed by low-resolution HLA typing methods at HLA-A and HLA-B loci and by high-resolution at HLA-DRB1, experienced the worst outcomes). The later has a great impact on the incidence and severity of GVHD, engraftment (i.e., neutrophil and platelet count recovery), as well as survival.

Conversely, it was shown that increasing the cell dose of HSC to over 3.5 × 107 TNC/kg could partially overcome those negative consequences, especially if the patients experienced previous autologous stem cell transplantations [10, 13]. Nevertheless, in adult recipients, the cell dose constitutes the major limitation which is difficult to overcome if less than two UCB units are used. Indeed, the use of two UCB units, preceded by the application of a reduced intensity preparative regimen, facilitated engraftment and mitigated the difficulties associated with delayed or nonengraftment [24–28].

Eventually, related CBT offers a good probability of success (e.g., possible low occurrence of transplant-related complications and transplant-related mortality (TRM)) as it is mainly associated with a low risk of GVHD [11–14, 29].

2. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation from Different Sources: Advantages and Disadvantages

2.1. Matched Unrelated Versus Umbilical Cord Blood or Haploidentical Transplantation

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a potentially curative option for many cases of hematologic nonmalignant or malignant diseases such as thalassemia major and acute leukemia. Applicability of HSCT is dependent on the presence of suitable hematopoietic stem cell donor. Unfortunately, many patients do not have suitable HLA match donor in family. Therefore, finding an alternative donor is crucial for such cases. The diversity of HLA antigens in community subsequently led to study several alternative sources HSCT such as the use of (i) unrelated donors bone marrow or peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cells, (ii) cord blood stem cells, (iii) finding a donor between extended family (especially in societies with high rate of consanguitniy in marriage), (iv) unrelated mismatch donor, and (v) haploidentical stem cell donor from a family member [30].

Each modality has its own advantages and disadvantages depending on the source of stem cells. Stem cells from live donor is well studied and shows good results when related HLA match donor HSCT is employed [31, 32]. Some advantages are associated with this modality such as (i) potential availability of the donor for further therapeutic maneuvers such as donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI)/boster cell doses or even retransplantation, in case of rejection or relapse, (ii) enough cell doses can be harvested for a successful and safe HSCT, (iii) high chance of finding a suitable donor, especially between white Caucasian race because of more advanced unrelated donor registries and highest number of donors in this population. Nevertheless, those advantages are balanced by some disadvantages such as (i) difficulty of finding a donor between ethnic minorities, (ii) great time consumption (average of 3 months) to find and prepare a donor for HSCT, (iii) unavailability of a potential donor due to personal donor problems, (iv) severe GVHD in case of HLA mismatches, usually greater than 2, (v) high cost of the overall procedure which limit its use in some countries financially limited.

Umbillical cord blood stem cells (UCBSCs) were extensively studied [3, 10, 33–36] and constitute an acceptable source of cells for permanent engraftment after transplantation. Further, they can elicit graft versus host/leukemia effect. UCBT has also its own advantages and disadvantages. Usually, there is a waste product of pregnancy deliveries, and so, UCBSCs represent valuable sources for preserving lives. The main advantages of this modality are related to (i) their easy and immediate availability [37], minimizing donor-related problems, (ii) their low risk of GVHD, thus allowing some acceptable degree of HLA mismatch [10, 33–35], (iv) their greater expansion and division potential than adult cells that makes the use of one Log cell dose lower than adult cells acceptable for a successful transplantation [38], (v) their nature as immunological naïve cells that might explain lower immunological complications than adult stem cells after UCBT [39–41]. Disadvantages of UCBSCs for transplantation often concern (i) their harvesting limitation that may be lower than the minimum necessary cells dose for a suitable engraftment, especially in adults with larger body mass [10, 33–35], (ii) availability of donors for further therapeutic maneuvers such as DLI and, so, in case of rejection/relapse, fewer therapeutic options remain. One of the major disadvantages of UCBT is the delayed engraftment which predisposes patients to severe infectious complications after transplantation [10, 33–35]. Finally, the cost of harvesting and preserving in frozen condition UCBSCs for several years is high and is not favorable for financially poor patients.

Considering the advantages of HSCT, the improvement of transplantation methods, the better knowledge of transplantation immunology, the development of more potent immunosuppressive drugs and antibiotics, the greater experience with mismatch transplantation as well as the possibility of stem cell purification in clinical setting, UCBSCs transplantation rose as a valuable therapeutic option. This option is generally used from family donor with similarity in HLA antigens in one haplotype [42–44]. This is possible by (i) using induction of greater immunosuppression in recipient to prevent from graft rejection and severe GVHD, (ii) purifying HSCs before HSCT and depletion of alloreactive T cells before transplantation, which can be performed by ex vivo T cell depletion or in vivo T cell reduction by T cell directed monoclonal antibodoies [45] or cyclophosphamide [46], and (iii) using higher cell doses (or even mega cell doses) to prevent rejection of transplanted cells by persistent recipient immunity [44].

Advantages of haploidentical transplantation are obvious. They include (i) universally availability of sibling donors (i.e., parents) for every therapeutic maneuvers (e.g., DLI or retransplant), (ii) short time for finding a suitable donor, (iii) great immunologic reactions against leukemic cells [47], (iv) acceptable cost which is very important for countries with limited financial resources. The disadvantages of haploidentical transplantation include (i) great possibility of rejection, due to preserved recipient immune system or severe GVHD and, (ii) high rate of infectious complications, [48] or posttransplantation secondary malignancies, because of greater and longer immunosupression necessary for prevention of immunological reactions and rejection, (iii) lesser knowledge and experience to manage the eventual complications associated to this procedure.

Although HSCT performed from all of these sources, there are few studies that compare between these modalities. Because of lack of enough evidence for comparison of these modalities, decision making for patients and choosing one of these options remain difficult.

3. Importance of Cord Blood Content and Obstetric Factors on Cord Blood Selection

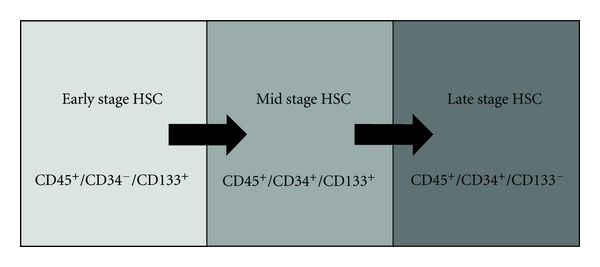

Although UCB is known to have transplant outcome advantages over bone marrow and peripheral blood, one of the known limitations of the use of UCB has been cell number and content [49, 50]. Variability between UCB units can be analysed in terms of (i) child gender, (ii) obstetric history, (iii) infant birth weight, (iv) gestational stage at parturition, and (v) mother's age at delivery [51]. These factors affect not only choice of cord blood unit for haematological transplantation, but also choice of processing technique. The recommended TNC content for UCB transplantation is a minimum of 2 × 107/kg for adults and 3.7 × 107/kg for children [52]. Therefore, it is extremely important to determine the best selection processes for donors of UCB to improve quality and applicability of UCB units and in terms of cord blood banking to reduce storage of ineffective blood units (Table 1). UCB cellular subpopulations of interest to transplant can be divided into three distinct groups according to a model previously described [53] from primitive to mature stem cells (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Important surface markers for quantification of human umbilical cord blood content.

| Human CD antigens | Cell types expressed on | CD function |

|---|---|---|

| CD3 | T cells, thymocyte subset | With TCR, TCR surface expression/signal transduction |

| CD4 | Thymocyte subset, T subset, monocytes, macrophages | MHC class II coreceptor, HIV receptor, T cell differentiation/activation |

| CD8 | Thymocyte subset, T subset, NK | MHC class I coreceptor, receptor for some mutated HIV-1, T cell differentiation/activation |

| CD11c | DC, myeloid cells, NK, B, T subset | Binds CD54, fibrinogen, and iC3b |

| CD17 | Neutrophils, mono, platelets | Lactosylceramide |

| CD19 | B, FDC | Complex w/CD21 and CD81, BCR coreceptor, B cell activation/differentiation |

| CD25 | Tact, Bact, lymph progenitors | IL-2Rα, w/IL-2Rβ, and γ to form high affinity complex |

| CD34 | Haematopoietic precursors, capillary endothelial, embryonic fibroblasts | Stem cell marker, adhesion, CD62L receptor |

| CD45 | Haematopoietic cells, multiple isoforms from alternative splicing | Tyrosine phosphatase, enhanced TCR, and BCR signals |

| CD56 | NK, T subset, neurones, some large granular lymphocyte leukemias, myeloid leukemias | Adhesion |

| CD123 | Lymph subset, basophils, haematopoietic progenitors, macrophages, DC, megakaryocytes | IL-3Rα, w/CDw131 |

| CD133 | Haematopoietic stem cell subset, epithelial, endothelial | Adhesion |

| 7ADD | Nucleic acid attachment | Apoptosis marker and viability assessment |

| Lin1 | CD3; T-lymphocytes CD14; monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils and eosinophils, CD16; NK-lymphocytes, macrophages, cultured monocytes and neutrophils, CD19/CD20; B-lymphocytes, CD56; activated and resting NK-lymphocytes |

With TCR, TCR surface expression/signal transduction. Pattern recognition receptor Fc receptor B-cell coreceptor Adhesion molecule |

| HLA-DR | Macrophages, B-cells and dendritic cells | MHC class II cell surface marker |

Figure 1.

Subtyping of HSCs. HSC differentiation has a specific pattern from early to mid to late stages defined by surface antigen expression.

Our work in this area showed that females tend to have an insignificantly higher UCB TNC than males (P = 0.752), but a greater concentration of T-cells (CD34+/CD3+) than male infants (P < 0.001) although a slightly higher trend in early stage HSC (CD45+/CD34−/CD133+, P = 0.8929) and late stage HSC (CD45+/CD34+/CD133−, P = 0.9479) subtypes were observed, the differences between male and female were still not be marked [51].

Obstetric history does have a higher effect on UCB content, with number of pregnancies having a marked effect with (i) significantly decreasing UCB TNC in subsequent pregnancies (P < 0.0001), (ii) similarly decreasing early stage HSC populations, dendritic cells expressing MHC class II surface antigens (Lin1−/CD11c+/HLA-DR+), and activated T-cells (CD45+/CD56+/CD3−) (all P value of <0.001) [51].

Infant birth weight also impacts on UCB cellularity. In a study of birth weights from 2.585 kg to 4.425 kg (average 3.571 kg ± SD 0.44), data illustrates that babies with lowest birth weight also have lowest TNC (P < 0.0001) but exceptions can be found. Birth weight also impacts on HSC concentrations, especially at mid-stage HSC. As birth weight rises, HSC concentration as well (P < 0.001). A birth weight between 3.25 and 3.75 kg gives an optimum yield of dendritic cells expressing MHC class II (Lin1/CD11c+/HLA-DR+) and T-cells similarly rise (P < 0.001) [51].

In investigating pregnancy length, the standard expected of a 40-week-period (280 days) is not always achieved. Our work shows that babies born early or late by only a few weeks can have differing levels of cellularity in the cord blood. TNC levels of early and late children are lower (P < 0.001). Late stage gestational periods results in higher levels of T-cells and late-stage HSC (P < 0.001). On the other hand, optimal B-cell levels require a gestational length of 38–40 weeks [51].

In many societies, the family decision to wait to have children has been questioned from a developmental point of view. In our work, mother's age at parturition between ages 18–43 has a significant effect on the UCB content. As mother's age increases, HSC concentration reduces, particularly late stage HSC (P < 0.0001), as does regulatory T-cells (CD45+/CD4+/CD3+), and indeed all lymphocytes (P < 0.001). However, mother's under the age of 20 and over the age of 37 tend to have babies with lower TNC than mother's that lie within that age range (P < 0.001) [51].

Therefore, results would indicate that the most likely units to be useful for UCB banking and transplantation come from full term larger babies who are born to younger mothers with few previous pregnancies [51]. These findings could be of significant interest to immunologists, since lower TNC and fewer lymphocytes may have an impact on the health of the child itself. Since several obstetric factors affect T-cell concentration, infants born late into larger families may warrant further immunological investigation, particularly to older mothers, but conventional wisdom that prematurity is a negative influence on immunity is upheld when UCB units of full term large babies have good levels of lymphocytes [54–56].

Despite the interesting data on obstetric factors and cord blood content, many of the studies have been country specific. This observation highlights the need for a true international study to evaluate UCB content in terms of regional variations, including ethnicity, average height and weight of the mother—since it is well known that in some Asian countries the female average height is lower, and finally differences between vaginal and caesarean delivery methods.

4. Approaches to Improve Cord Blood Stem Cell Expansion and Engraftment

Increased cell dose and improved homing are two major concerns prevailing in efforts to overcome engraftment delay following UCBT [27]. There is a strong association between these strategies to reconstitute hematopoetic system after UCBT which are discussed here. There are many unknown aspects about the interaction of hematopoietic components. However, designing ex-vivo experiments based on in vivo conditions shall naturally lead to more findings. Expansion of UCB-HSCs is an approach to increase cell dose and make UCB-HSC applicable for adult transplantation. Ex vivo expansion is performed through various ways: modifications in liquid culture, stromal coculture, and perfusion in bioreactors [57]. Reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens, double cord blood transplantation, direct intra-BM injection of CB grafts, notch ligand expansion, as well as SDF-1/CXCR4 targeting represent new promising approaches to shorten CBT engraftment time [12].

4.1. Cytokine-Mediated Expansion

A wide variety of cytokine cocktails, growth factors, or other biological mediators in liquid culture have been assessed. Cytokines such as stem cell factor (SCF), interleukin (IL)-3, IL-6 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), thrombopoietin (TPO), and Flt-3 ligand (FL) have been extensively used with various dose or culture length [58]. However, the heterogeneity of CB samples and experimental conditions causes inconsistency among results and there is no specific growth factor cocktail that is universally applicable. Recently, a two-step expansion system proposed by McNiece et al. [59] yielded more than 400-fold increase in TNC and 20-fold increase in CD34+cells, which is more effective than single step expansion [60]. Cytokine-based expansion has not proved any definitive evidence for stem cell expansion for clinical purposes.

4.2. Neuropeptides

The complex hematopoiesis network consists of nonhematopoietic cells, hematopoietic cells, as well as various ranges of biological mediators such as hormones, cytokines, and neurotransmitters. However, until recently, enough evidence regarding the role of neuropeptides on UCB CD34+ cells was not available. Research had indicated that inclusion of biological mediators other than cytokines, such as neuropeptides would be valuable for optimization of UCB-HSC ex vivo expansion and shortening engraftment time [61]. Accordingly, once the role of substance P (SP) and calcitonin-gene-related neuropeptides (CGRP) on the expansion of UCB CD34+ cells was investigated [62], results showed maximum expansion in 10−9 M of neuropeptides in short time culture. Synergistic and antagonistic effects of both SP and CGRP were dominant at 10−9 M and 10−7 M dose on total nucleated cells and CD34+ CD38− cells, respectively [62]. Interestingly, concentration 10−9 M of SP leds to optimal production of SCF and IL1 in BM stroma [63]. It seems that the proliferation of immuohematopoietic cells resulted as consequence of these interactions. Based on these preliminary findings, identifying further neuropeptide and UCB-HSC interactions would be helpful to achieve an optimum growth factor cocktail for expansion.

4.3. Coculture and Coinfusion with Stromal Cells

Growth factor cocktails use in ex vivo expansion partially compensates lack of natural hematopoietic microenvironment. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)/stromal coculture is an optional modification to resemble the hematopoietic microenvironment. Coinfusion of MSCs—which is suitable for immunomodulation and prevention of GVHD—and employment of HSCs is another potential strategy to facilitate engraftment. Furthermore, immunomodulatory properties of MSCs make them a desirable cell for this purpose. There is little controversial evidence about UCB-derived MSCs and most experiments are performed on marrow-derived cells. Hematopoetic engraftment is supported by MSC through neurogenic and angiogenic mechanisms. Therefore, it has been proposed that coinfusion of MSC and hematopoietic cells accelerate engraftment of UCB [58, 64].

4.4. Tetraethylenepentamine- (TEPA-) Mediated Expansion

Reduction of free copper content and oxidative stress level of HSCs is the main suggested reason for induction of ex-vivo expansion of HSCs by tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA) treatment. An increase of 89-fold in CD34+ cells was achieved by polyamine copper chelator, -TEPA-in Peled et al. experiment [65]. TEPA mediated expansion studies are in phase I/II clinical trials [12].

4.5. Notch Ligand-Based Expansion

Notch-1 gene expressed in CD34+ hematopoietic precursor cells is involved in self-renewal of repopulating cells. For expansion in static culture an immobilized, engineered notch ligand Delta1 with cytokine cocktail (SCF, FL, IL-6, TPO, and IL-3) was investigated in experiment [66]. Immobilized notch ligand results in improved immune reconstitution and enhanced cell number and phase I/II clinical trials are underway. Delaney et al. showed that coinfusion of unmanipulated UCB and notch-mediated ex vivo expanded UCB had faster neutrophil engraftment, 16 days, compared to infusion of unmanipulated double UCBT, which took 26 days [66]. More clinical trials are required to support these results.

4.6. Adhesion Molecules for HSC Homing

Adhesion molecules are involved in the regulation of survival, proliferation and differentiation of progenitor cells. This might occur through interaction with microenvironment components [67] and biological mediators such as cytokines, chemokines, and neuropeptides. Secretion of stromal-derived factor (SDF)-1 by BM stromal cells is crucial for retention/homing of HSC in BM [26]. Additionally, involvement of this axis in survival and proliferation of HSCs has been shown [12]. For HSC engraftment, CXCR4 response to SDF1 and SDF-1 expression in BM microenvironment is important [26]. To improve homing of HSC following CBT, several approaches have been considered. Inhibition of enzymatic activity of CD26/Dipeptidylpeptidase IV (DPPIV) avoids truncation of SDF-1/CXCL12-exclusive ligand for CXCR4, and consequently results in acceleraed UCB-HSC engraftment. Additionally, in order to increase the responsiveness of SDF1/CXCR4, ex vivo priming of HSCs prior to transplantation with small molecules including C3 complement fragments, fibronectin, fibrinogen, and hyaluronic acid has been suggested to improve homing/engraftment of UCB-HSCs [26].

Recently, SP and CGRP neuropeptide treated CB stem cells showed increased percentage of CD34+/CXCR4 [68], CD49e, and CD44 [69] subsets in neuropeptide-cytokine treated cells compared to cytokine-treated cells in short time culture, as well as a resistance to frequency decline. Accordingly, since actions of neuropeptides on hematopoeisis are less known, more investigation to clarify underlying mechanisms is required.

5. Cord Blood Stem Cells Transplantation: A Potential Cure for Blood Diseases

5.1. Main Interventions in Malignant and Nonmalignant Blood Diseases

In children and adults with hematologic malignancies (i.e., lymphoid- and myeloid-), most clinical studies were performed in an unrelated donor setting and reported that the TNC dose contained in a UCB unit has a profound impact on engraftment and an effect on infection risk and survival [8, 9, 19, 20, 22, 23, 70, 71]. In addition, the degree of HLA matching as well as the indication of UCBT according the cancer stage seemed to have an independent impact on outcome (i.e., recipients who had more than two HLA mismatches and/or with advanced-stage malignant diseases experienced the worst outcomes) [4, 22, 23]. Over the past two decades, important changes (e.g., better selection of UCB donor units, greater selection of suitable transplantation recipients, more supportive experienced care) have improved outcomes [10, 12]. In hematologic nonmalignancies, such as thalassemia and sickle cell disease (SCD), it has been reported that graft rejection as well as delayed or failed engraftment after UCBT, represent the two major barriers, although often counter-balanced by the benefit of lower risk GVHD [8, 20, 72–74].

Here, we provide two relevant examples of blood diseases for which UCBT has been frequently reported. Thereby, we will discuss the case of leukemia, especially acute leukemia, as an example of UCBT in blood malignancy as well as thalassemia, especially thalassemia major, as an example of nonmalignant disorder.

5.2. Case of Leukemia

UCBT outcome for leukemia is widely documented since the nineties of the last century, mostly in pediatric patients with acute leukemia (i.e., 30–50% in most series) [7, 8, 20, 21, 70, 75, 76]. However, outcomes of other subsets of the disease (e.g., chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) formerly known as pre-leukemia) after UCBT are mainly limited by the number of patients [77–83]. Overall, data supports the utilization of UCB as an alternative source of HSC for patients with low- and high-risk leukemia and/or with no HLA-matched unrelated donor. Nevertheless, in patients with CML, low engraftment—certainly due to small cell dose—and moderate overall survival (40–60%) was observed after UBCT and, in spite of low relapse rates (about 10%), UBCT is not highly desired [79–81].

In acute leukemia patients, the neutrophil engraftment rate was reported to be about 60–80%, the TRM rate of about 44%, the relapse rate of approximately 20–40%, and the event- (leukemia-) free survival (EFS) rate at 2 years was ranged between 30 and 50% [9, 19, 84, 85]. In children with acute leukemia who received better HLA-matched grafts and higher cell dose achieved better survival [85]. In adults with acute leukemia, recent studies [33, 34, 86–90] showed that outcomes after UCBT were manifested by lower risk of TRM and similar EFS compared to unrelated (matched or mismatched) donor BM after myeloablative conditioning (cyclophosphamide/total body irradiation). Interestingly, double UBCT can overcome the cell dose limitation imposed by UCB grafts in adults while favoring a lower relapse risk [91].

Besides, reports evaluating the outcomes of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) after UCBT showed promises according to the graft selection and disease stage at transplantation [92, 93]. Indeed, it was shown that myeloablative UCBT, influenced by TNC, achieved neutrophil recovery (94%–96%), sustained platelet recovery (73%–89%), EFS rate of about 77% at 2 years and about 37% at 4 years, incidence of TRM of about 39%, and relapse rate of approximately 19% at 2 years [24, 94].

In nonmyeloablative settings, studies are required to assess the outcomes leukemia outcomes after reduced-intensity conditioning [24, 94].

Eventually, overall data support the utilization of UCB as an alternative source of HSCT for patients with acute leukemia who lack a suitable related donor.

5.3. Case of Thalassemia

UCBT become a valuable alternative to overcome lack of both safety (i.e., GVHD) and HLA-identical sibling donor associated with conventional BMT, which initially demonstrated (about 30 years ago) a curative potential for thalassemia major, the severe form of this genetic hemoglobinopathy [95].

In one retrospective survey of sibling/related donor cord blood transplantation, about 21% children with thalassemia developed graft rejection after transplantation, the EFS was approximately 79%, acute and chronic GVHD were low (about 6%) and, remarkably, none of the patients (n = 33) died [73]. Interestingly, the graft rejection was often associated with the type of conditioning regimen. Thereby, a conditioning regimen of busulfan (BU) and cyclophosphamide (CY), with or without antithymocyte globulin (ATG), had a significant association with graft rejection after UCB transplantation for thalassemia [73]. However, children with thalassemia prepared for CBT with a combination of BU, fludarabine (Flu) or CY, and thiotepa (TT) and received cyclosporine alone for postgrafting immunosuppression, exerted very positive outcomes (high EFS rate enhanced from 62% to 94% if CY was used instead of Fly; no acute or chronic GVHD) [73]. UCBT using unrelated donors as a potential cure for thalassemia requires large series of patients [96]. Thalassemiarecipients typically received unrelated cord blood units with 1 or 2 HLA mismatches and are prepared with a conventional combination of BU/CY/ATG. Most studies, mainly in children, showed good outcomes after unrelated UCBT: limited chronic GVHD, relatively rapid and good neutrophil and platelet count recovery, low TRM and high EFS rate [97, 98]. Graft failure or was autologous recovery were the main limitations.

Thus, the development of UCB as an alternate source of hematopoietic cells in transplantation for thalassemia must be linked to an effort to increase the UCB inventory with high-quality units collected from an ethnically representative population.

6. Conclusion

It is difficult to compare older transplantation outcome reports with more recent studies (i.e., comprehensive metaanalysis) because of changes mainly related to (i) stem cell sources (UCB unit characteristics), (ii) year of transplantation, (iii) time from diagnosis to transplantation, (iv) disease stage, (v) methodology of HLA-typing, (vi) conditioning regimen formulation, and (vii) standard of the cell dose that must be available in a single UCB unit to be infused.

However, UCBT offers an attractive alternative to BMT, in particular because of the low incidence of GVHD. Indeed, although UBCT is associated with a greater risk of graft rejection, due in part to a restricted number of hematopoietic stem cells, nevertheless, this risk can be overcome in part by selecting UCB units that contain a large number of cells and those that are closely matched at the HLA loci.

Alternatively, the use of double UCBT from unrelated donors or the potential collection of HSCs from human placenta might be useful approaches to optimize the donor hematopoietic stem cell content. Interestingly, recent results show excellent outcomes after HLA-identical sibling UCBT, stressing the importance of collecting cord blood in families when a child is affected by blood disorders. Eventually, recent studies reported that combination of UCB unit collected after a sibling birth with a marrow harvested from the same donor presented excellent results exerted by both low rates of GVHD and graft rejection. Most recent studies aim to optimize UCBT and promising results were obtained once the cell dose was increased and the homing improved taking into consideration several microenvironmental factors (e.g., cytokines, neuropeptides) and cells (e.g., mesenchymal stem cells).

The field of human hematotherapy was transformed with the advent of bone marrow replacement and augmented by the application of umbilical cord blood units. The increasing number of cord blood banks around the world makes sourcing of units an increased potential and has begun to slowly outweigh the need for bone marrow registries. Despite this, the costs involved are still unaffordable to many countries, not least in developing nations. Changes in the processing procedures, our knowledge of the true content of cord blood from children of different backgrounds, and from mothers of different ages and heatlh status, and the advent of new technologies will hopefully make availability of umbilical cord blood transplantation a reality in every nation in the future.

Authors' Contribution

All authors have equally contributed to this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Abder Menaa, M. D., for his suggestions after pertinent revision of this paper. They also thank Saba Habibollah, Christina Basford, and Nico Forraz for data analysis.

References

- 1.Halbrecht J. Transfusion with placental blood. The Lancet. 1939;233(6022):202–203. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ende M, Ende N. Hematopoietic transplantation by means of fetal (cord) blood. A new method. Virginia Medical Monthly. 1972;99(3):276–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gluckman E, Broxmeyer HE, Auerbach AD, et al. Hematopoietic reconstitution in a patient with Fanconi’s anemia by means of umbilical-cord blood from an HLA-identical sibling. New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;321(17):1174–1178. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198910263211707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broxmeyer HE, Smith FO. Thomas’ Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Malden, Mass, USA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. Cord blood hematopoietic cell transplantation; pp. 559–576. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hough R, Rocha V. Transplant outcomes in acute leukemia (II) Seminars in Hematology. 2010;47(1):51–58. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacMillan ML, Walters MC, Gluckman E. Transplant outcomes in bone marrow failure syndromes and hemoglobinopathies. Seminars in Hematology. 2010;47(1):37–45. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner JE, Kernan NA, Steinbuch M, Broxmeyer HE, Gluckman E. Allogeneic sibling umbilical-cord-blood transplantation in children with malignant and non-malignant disease. The Lancet. 1995;346(8969):214–219. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91268-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gluckman E, Rocha V, Boyer-Chammard A, et al. Outcome of cord-blood transplantation from related and unrelated donors. Eurocord transplant group and the European blood and marrow transplantation group. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(6):373–381. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708073370602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Locatelli F, Rocha V, Chastang C, et al. Factors associated with outcome after cord blood transplantation in children with acute leukemia. Blood. 1999;93(11):3662–3671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocha V, Gluckman E. Improving outcomes of cord blood transplantation: HLA matching, cell dose and other graft- and transplantation-related factors. British Journal of Haematology. 2009;147(2):262–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broxmeyer HE. Umbilical cord transplantation: epilogue. Seminars in Hematology. 2010;47(1):97–103. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rocha V, Broxmeyer HE. New approaches for improving engraftment after cord blood transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010;16(supplement 1):S126–S132. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen G, Carter SL, Weinberg KI, et al. Antigen-specific T-lymphocyte function after cord blood transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12(12):1335–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocha V, Locatelli F. Searching for alternative hematopoietic stem cell donors for pediatric patients. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2008;41(2):207–214. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eapen M, Rubinstein P, Zhang MJ, et al. Outcomes of transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood and bone marrow in children with acute leukaemia: a comparison study. The Lancet. 2007;369(9577):1947–1954. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60915-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prasad VK, Kurtzberg J. Umbilical cord blood transplantation for non-malignant diseases. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2009;44(10):643–651. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gluckman E, Rocha V, Ionescu I, et al. Results of unrelated cord blood transplant in Fanconi anemia patients: risk factor analysis for engraftment and survival. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2007;13(9):1073–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willasch A, Hoelle W, Kreyenberg H, et al. Outcome of allogeneic stem cell transplantation in children with non-malignant diseases. Haematologica. 2006;91(6):788–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michel G, Rocha V, Chevret S, et al. Unrelated cord blood transplantation for childhood acute myeloid leukemia: a Eurocord Group analysis. Blood. 2003;102(13):4290–4297. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubinstein P, Carrier C, Scaradavou A, et al. Outcomes among 562 recipients of placental-blood transplants from unrelated donors. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339(22):1565–1577. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811263392201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner JE, Barker JN, DeFor TE, et al. Transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood in 102 patients with malignant and nonmalignant diseases: influence of CD34 cell dose and HLA disparity on treatment-related mortality and survival. Blood. 2002;100(5):1611–1618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rocha V, Sanz G, Gluckman E. Umbilical cord blood transplantation. Current Opinion in Hematology. 2004;11(6):375–385. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000145933.36985.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gluckman E, Rocha V, Arcese W, et al. Factors associated with outcomes of unrelated cord blood transplant: guidelines for donor choice. Experimental Hematology. 2004;32(4):397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunstein CG, Barker JN, Weisdorf DJ, et al. Umbilical cord blood transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning: impact on transplantation outcomes in 110 adults with hematologic disease. Blood. 2007;110(8):3064–3070. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-067215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barker JN, Weisdorf DJ, DeFor TE, et al. Transplantation of 2 partially HLA-matched umbilical cord blood units to enhance engraftment in adults with hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2005;105(3):1343–1347. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delaney C, Ratajczak MZ, Laughlin MJ. Strategies to enhance umbilical cord blood stem cell engraftment in adult patients. Expert Review of Hematology. 2010;3(3):273–283. doi: 10.1586/ehm.10.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanevsky A, Shimoni A, Yerushalmi R, Nagler A. Cord blood stem cells for hematopoietic transplantation. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports. 2011;7(2):425–433. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gutman JA, Riddell SR, McGoldrick S, Delaney C. Double unit cord blood transplantation: who wins-and why do we care? Chimerism. 2010;1(1):21–22. doi: 10.4161/chim.1.1.12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocha V, Wagner JE, Sobocinski KA, et al. Graft-versus-host disease in children who have received a cord blood or bone marrow transplant from an HLA-identical sibling. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(25):1846–1854. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazarus HM. Acute leukemia in adults: novel allogeneic transplant strategies. Hematology. 2012;17(supplement 1):47–51. doi: 10.1179/102453312X13336169155493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang M-J, Davies SM, Camitta BM, Logan B, Tiedemann K, Eapen M. Comparison of outcomes after HLA-matched sibling and unrelated donor transplantation for children with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2012;18(8):1204–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez LE. Outcomes from unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer Control. 2011;18(4):216–221. doi: 10.1177/107327481101800402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eapen M, Rocha V, Sanz G, et al. Effect of graft source on unrelated donor haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation in adults with acute leukaemia: a retrospective analysis. The Lancet Oncology. 2010;11(7):653–660. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70127-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laughlin MJ, Eapen M, Rubinstein P, et al. Outcomes after transplantation of cord blood or bone marrow from unrelated donors in adults with leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(22):2265–2275. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurtzberg J, Laughlin M, Graham ML, et al. Placental blood as a source of hematopoietic stem cells for transplantation into unrelated recipients. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(3):157–166. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607183350303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghavamzadeh A, Alimoghaddam K, Naderi A, et al. Outcome of related and unrelated cord-blood transplantation in children at hematopoietic stem cell transplantation research center of Shariati Hospital. International Journal of Hematology-Oncology and Stem Cell Research. 2009;3(1):17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barker JN, Krepski TP, DeFor TE, Davies SM, Wagner JE, Weisdorf DJ. Searching for unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cells: availability and speed of umbilical cord blood versus bone marrow. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2002;8(5):257–260. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12064362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Broxmeyer HE, Gluckman E, Auerbach A, et al. Human umbilical cord blood: a clinically useful source of transplantable hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. International Journal of Cell Cloning. 1990;8(supplement 1):76–91. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530080708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deacock SJ, Schwarer AP, Bridge J, Batchelor JR, Goldman JM, Lechler RI. Evidence that umbilical cord blood contains a higher frequency of HLA class II-specific alloreactive T cells than adult peripheral blood: a limiting dilution analysis. Transplantation. 1992;53(5):1128–1134. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199205000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roncarolo MG, Bigler M, Ciuti E, Martino S, Tovo PA. Immune responses by cord blood cells. Blood Cells. 1994;20(2-3):573–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bensussan A, Gluckman E, El Marsafy S, et al. BY55 monoclonal antibody delineates within human cord blood and bone marrow lymphocytes distinct cell subsets mediating cytotoxic activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(19):9136–9140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang XJ, Liu DH, Liu KY, et al. Treatment of acute leukemia with unmanipulated HLA-mismatched/haploidentical blood and bone marrow transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2009;15(2):257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ciceri F, Labopin M, Aversa F, et al. A survey of fully haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in adults with high-risk acute leukemia: a risk factor analysis of outcomes for patients in remission at transplantation. Blood. 2008;112(9):3574–3581. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aversa F, Terenzi A, Tabilio A, et al. Full haplotype-mismatched hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a phase II study in patients with acute leukemia at high risk of relapse. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(15):3447–3454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naparstek E, Delukina M, Or R, et al. Engraftment of marrow allografts treated with Campath-1 monoclonal antibodies. Experimental Hematology. 1999;27(7):1210–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prigozhina TB, Gurevitch O, Slavin S. Nonmyeloablative conditioning to induce bilateral tolerance after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in mice. Experimental Hematology. 1999;27(10):1503–1510. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Capanni M, et al. Donor natural killer cell allorecognition of missing self in haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: challenging its predictive value. Blood. 2007;110(1):433–440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-038687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perruccio K, Tosti A, Burchielli E, et al. Transferring functional immune responses to pathogens after haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation. Blood. 2005;106(13):4397–4406. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGuckin CP, Forraz N, Baradez MO, et al. Production of stem cells with embryonic characteristics from human umbilical cord blood. Cell Proliferation. 2005;38(4):245–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2005.00346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basford C, Forraz N, McGuckin C. Optimized multiparametric immunophenotyping of umbilical cord blood cells by flow cytometry. Nature Protocols. 2010;5(7):1337–1346. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGuckin CP, Basford C, Hanger K, Habibollah S, Forraz N. Cord blood revelations: the importance of being a first born girl, big, on time and to a young mother! Early Human Development. 2007;83(12):733–741. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mancinelli F, Tamburini A, Spagnoli A, et al. Optimizing umbilical cord blood collection: impact of obstetric factors versus quality of cord blood units. Transplantation Proceedings. 2006;38(4):1174–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McGuckin CP, Pearce D, Forraz N, Tooze JA, Watt SM, Pettengell R. Multiparametric analysis of immature cell populations in umbilical cord blood and bone marrow. European Journal of Haematology. 2003;71(5):341–350. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2003.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tommiska V, Heinonen K, Ikonen S, et al. A national short-term follow-Up study of extremely low birth weight infants born in Finland in 1996-1997. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):p. E2. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adkins B. T-cell function in newborn mice and humans. Immunology Today. 1999;20(7):330–335. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li J, Barreda DR, Zhang YA, et al. B lymphocytes from early vertebrates have potent phagocytic and microbicidal abilities. Nature Immunology. 2006;7(10):1116–1124. doi: 10.1038/ni1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liao Y, Geyer MB, Yang AJ, Cairo MS. Cord blood transplantation and stem cell regenerative potential. Experimental Hematology. 2011;39(4):393–412. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tung SS, Parmar S, Robinson SN, De Lima M, Shpallemail EJ. Ex vivo expansion of umbilical cord blood for transplantation. Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology. 2010;23(2):245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McNiece I, Kubegov D, Kerzic P, Shpall EJ, Gross S. Increased expansion and differentiation of cord blood products using a two-step expansion culture. Experimental Hematology. 2000;28(10):1181–1186. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shpall EJ, Quinones R, Giller R, et al. Transplantation of ex vivo expanded cord blood. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2002;8(7):368–376. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12171483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ebtekar M, Shahrokhi S, Alimoghaddam K. Characteristics of Cord Blood Stem Cells: Role of Substance P, (SP) and Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP), Stem Cells and Cancer Stem Cells. Vol. 2. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Netherlands; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shahrokhi S, Ebtekar M, Alimoghaddam K, et al. Substance P and calcitonin gene-related neuropeptides as novel growth factors for ex vivo expansion of cord blood CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells. Growth Factors. 2010;28(1):66–73. doi: 10.3109/08977190903369404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rameshwar P, Ganea D, Gascon P. In vitro stimulatory effect of Substance P on hematopoiesis. Blood. 1993;81(2):391–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McKenna D, Sheth J. Umbilical cord blood: current status and promise for the future. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2011;134:261–269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peled T, Mandel J, Goudsmid RN, et al. Pre-clinical development of cord blood-derived progenitor cell graft expanded ex vivo with cytokines and the polyamine copper chelator tetraethylenepentamine. Cytotherapy. 2004;6(4):344–355. doi: 10.1080/14653240410004916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Delaney C, Heimfeld S, Brashem-Stein C, Voorhies H, Manger RL, Bernstein ID. Notch-mediated expansion of human cord blood progenitor cells capable of rapid myeloid reconstitution. Nature Medicine. 2010;16(2):232–236. doi: 10.1038/nm.2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verfaillie CM. Adhesion receptors as regulators of the hematopoietic process. Blood. 1998;92(8):2609–2612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shahrokhi S, Ebtekar M, Alimoghaddam K, et al. Communication of substance P, calcitonin-gene-related neuropeptides and chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) in cord blood hematopoietic stem cells. Neuropeptides. 2010;44(5):385–389. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shahrokhi S, Alimoghaddam K, Ebtekar M, et al. Effects of neuropeptide substance P on the expression of adhesion molecules in cord blood hematopoietic stem cells. Annals of Hematology. 2010;89(12):1197–1205. doi: 10.1007/s00277-010-1006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Laughlin MJ, Barker J, Bambach B, et al. Hematopoietic engraftment and survival in adult recipients of umbilical-cord blood from unrelated donors. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(24):1815–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106143442402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barker JN, Davies SM, DeFor T, Ramsay NKC, Weisdorf DJ, Wagner JE. Survival after transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood is comparable to that of human leukocyte antigen-matched unrelated donor bone marrow: results of a matched-pair analysis. Blood. 2001;97(10):2957–2961. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pinto FO, Roberts I. Cord blood stem cell transplantation for haemoglobinopathies. British Journal of Haematology. 2008;141(3):309–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Locatelli F, Rocha V, Reed W, et al. Related umbilical cord blood transplantation in patients with thalassemia and sickle cell disease. Blood. 2003;101(6):2137–2143. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Adamkiewicz TV, Szabolcs P, Haight A, et al. Unrelated cord blood transplantation in children with sickle cell disease: review of four-center experience. Pediatric Transplantation. 2007;11(6):641–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wagner JE, Rosenthal J, Sweetman R, et al. Successful transplantation of HLA-matched and HLA-mismatched umbilical cord blood from unrelated donors: analysis of engraftment and acute graft- versus-host disease. Blood. 1996;88(3):795–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kurtzberg J, Graham M, Casey J, Olson J, Stevens CE, Rubinstein P. The use of umbilical cord blood in mismatched related and unrelated hemopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood Cells. 1994;20(2-3):275–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maschan AA, Skorobogatova EV, Samotchatova EV, et al. A successful cord blood transplant in a child with second accelerated phase chronic myeloid leukemia following lymphoid blast crisis. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2000;25(2):213–215. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pecora AL, Stiff P, Jennis A, et al. Prompt and durable engraftment in two older adult patients with high risk chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) using ex vivo expanded and unmanipulated unrelated umbilical cord blood. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2000;25(7):797–799. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brunstein C, Setubal D, DeFor T, et al. Umbilical cord blood transplantation for adult patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2007;13(2):p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sanz GF, Saavedra S, Jiménez C, et al. Unrelated donor cord blood transplantation in adults with chronic myelogenous leukemia: results in nine patients from a single institution. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2001;27(7):693–701. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sanz J, Montesinos P, Saavedra S, et al. Single-unit umbilical cord blood transplantation from unrelated donors in adult patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010;16(11):1589–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sato A, Ooi J, Takahashi S, et al. Unrelated cord blood transplantation after myeloablative conditioning in adults with advanced myelodysplastic syndromes. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2011;46(2):257–261. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Warlick ED, Cioc A, DeFor T, Dolan M, Weisdorf D. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for adults with myelodysplastic syndromes: importance of pretransplant disease burden. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2009;15(1):30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wall DA, Carter SL, Kernan NA, et al. Busulfan/melphalan/antithymocyte globulin followed by unrelated donor cord blood transplantation for treatment of infant leukemia and leukemia in young children: the Cord Blood Transplantation study (COBLT) experience. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2005;11(8):637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kurtzberg J, Prasad VK, Carter SL, et al. Results of the cord blood transplantation study (COBLT): clinical outcomes of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood transplantation in pediatric patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2008;112(10):4318–4327. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-098020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rocha V, Labopin M, Sanz G, et al. Transplants of umbilical-cord blood or bone marrow from unrelated donors in adults with acute leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(22):2276–2285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Takahashi S, Ooi J, Tomonari A, et al. Comparative single-institute analysis of cord blood transplantation from unrelated donors with bone marrow or peripheral blood stem-cell transplants from related donors in adult patients with hematologic malignancies after myeloablative conditioning regimen. Blood. 2007;109(3):1322–1330. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-020172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kumar P, Defor TE, Brunstein C, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in adult acute lymphocytic leukemia: impact of donor source on survival. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2008;14(12):1394–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tomblyn MB, Arora M, Baker KS, et al. Myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: analysis of graft sources and long-term outcome. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(22):3634–3641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Atsuta Y, Suzuki R, Nagamura-Inoue T, et al. Disease-specific analyses of unrelated cord blood transplantation compared with unrelated bone marrow transplantation in adult patients with acute leukemia. Blood. 2009;113(8):1631–1638. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brunstein CG, Gutman JA, Weisdorf DJ, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematologic malignancy: relative risks and benefits of double umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2010;116(22):4693–4699. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-285304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ooi J, Iseki T, Takahashi S, et al. Unrelated cord blood transplantation for adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2004;103(2):489–491. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sanz J, Sanz MA, Saavedra S, et al. Cord blood transplantation from unrelated donors in adults with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010;16(1):86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ballen KK, Spitzer TR, Yeap BY, et al. Double unrelated reduced-intensity umbilical cord blood transplantation in adults. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2007;13(1):82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Thomas ED, Buckner CD, Sanders JE. Marrow transplantation for thalassaemia. The Lancet. 1982;2(8292):227–229. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jaing TH, Hung IJ, Yang CP, Chen SH, Sun CF, Chow R. Rapid and complete donor chimerism after unrelated mismatched cord blood transplantation in 5 children with β-thalassemia major. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2005;11(5):349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jaing TH, Yang CP, Hung IJ, Chen SH, Sun CF, Chow R. Transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood utilizing double-unit grafts for five teenagers with transfusion-dependent thalassemia. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2007;40(4):307–311. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jaing TH, Tan P, Rosenthal J, et al. 166: unrelated cord blood transplantation (UCBT) for transfusion-dependent thalassemia-a retrospective audited analysis of 41 consecutive patients. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2007;13(2):p. 62. [Google Scholar]