Abstract

Cellular communication across tissues is an essential process during embryonic development. Secreted factors with potent morphogenetic activity are key elements of this cross-talk, and precise regulation of their expression is required to elicit appropriate physiological responses. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are versatile post-transcriptional modulators of gene expression. However, the large number of putative targets for each miRNA hinders the identification of physiologically relevant miRNA-target interactions. Here we show that miR-1 and miR-206 negatively regulate angiogenesis during zebrafish development. Using target protectors, our results indicate that miR-1/206 directly regulate the levels of Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VegfA) in muscle, controlling the strength of angiogenic signaling to the endothelium. Conversely, reducing the levels of VegfAa, but not VegfAb, rescued the increase in angiogenesis observed when miR-1/206 were knocked down. These findings uncover a novel function for miR-1/206 in the control of developmental angiogenesis through the regulation of VegfA, and identify a key role for miRNAs as regulators of cross-tissue signaling.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, MicroRNA, miR-1, miR-206, VEGF

INTRODUCTION

Secreted signaling molecules are powerful regulators of development that are able to elicit behaviors such as proliferation, migration and differentiation in a concentration-dependent manner (Müller and Schier, 2011). Because these factors have potent morphogenetic functions, both their expression and the sensitivity of the receiving cells must be tightly regulated. Whereas low signaling levels would fail to elicit the appropriate response, excess signal could flood the system and eliminate positional and concentration-dependent information. One developmental context in which these signaling molecules play an important role is the formation of the vascular network. Secreted growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) function at different levels during the establishment and remodeling of the vasculature (Cao et al., 2008; Carmeliet and Jain, 2011; Chung and Ferrara, 2011; Ferrara et al., 2003; Turner and Grose, 2010). During zebrafish (Danio rerio) angiogenesis, VEGF is secreted from the muscle and plays a fundamental role in the expansion and remodeling of the vascular network by regulating the migration and proliferation of endothelial cells in the aorta to form the intersegmental vessels (ISVs) (Chung and Ferrara, 2011).

Much of our current knowledge regarding VEGF-mediated angiogenesis focuses on the regulation of the pathway downstream of the receptor in the receiving cells (Small and Olson, 2011), whereas the mechanisms that modulate the level of VEGF expressed by the producing cells are less well understood (Caporali and Emanueli, 2011). VEGFA expression is responsive to environmental changes and can be regulated at the post-transcriptional level through alternative splicing (Harper and Bates, 2008), motifs in its 3′UTR (Forsythe et al., 1996; Claffey et al., 1998) and alternative polyadenylation (Dibbens et al., 2001); however, the physiological role of these elements in development remains largely unexplored (Levy et al., 1998; Ciais et al., 2004; Onesto et al., 2004; Ray and Fox, 2007; Vumbaca et al., 2008; Ray et al., 2009; Jafarifar et al., 2011).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have recently emerged as fundamental post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression. These ~22 nt small RNAs repress target mRNA translation and induce mRNA deadenylation and decay (Djuranovic et al., 2011; Fabian et al., 2010; Huntzinger and Izaurralde, 2011). Thus, miRNAs provide an ideal mechanism to regulate potent signaling molecules that require dynamic yet accurate expression within an optimal range. Computational efforts indicate that a large fraction of vertebrate genes are under selective pressure to maintain putative miRNA target sites, and miRNAs have been estimated to regulate 30-50% of all genes in humans (Bartel, 2009; Friedman et al., 2009; Rajewsky, 2006). Because any given miRNA has the potential to regulate several hundred genes, a fundamental challenge in the field is to identify which miRNA-target interactions are physiologically relevant in vivo.

miR-1 and miR-206 are evolutionarily conserved miRNAs of highly similar sequence that share common expression in the muscle from C. elegans to human (Boutz et al., 2007; King et al., 2011; Lagos-Quintana et al., 2001; Lagos-Quintana et al., 2002; Sokol and Ambros, 2005). Our previous work analyzing the targetome of muscle miRNAs using zebrafish as a model system revealed that miR-1/206 play a fundamental role in shaping gene expression in the developing muscle (Mishima et al., 2009). Here, we modulate the expression and activity of miR-1/206 and demonstrate that they negatively regulate angiogenesis during zebrafish development. This effect is mediated, at least in part, by the direct regulation of the key angiogenic factor VegfAa, as blocking regulation of vegfaa by miR-1/206 using target protectors has a pro-angiogenic effect that recapitulates the loss of function of miR-1/206. Taken together, these findings identify miR-1/206 as key regulators of angiogenesis during zebrafish development. These results uncover a novel regulatory role for miRNAs, in which they control the cross-talk between the muscle and the vasculature to modulate the level of angiogenesis during development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Zebrafish care and maintenance

Zebrafish were maintained at 28°C in conditions as described (Westerfield, 2000). All protocols were in accordance with Yale University animal care guidelines. Details regarding the establishment and characterization of the transgenic lines used have been described elsewhere (Lawson and Weinstein, 2002).

miRNA target prediction

The collection of miR-1/206 targets compiled by Mishima et al. (Mishima et al., 2009) was scanned for genes with both a known role in angiogenesis and muscle-specific expression. The 3′UTRs of selected genes were analyzed for the presence of sites complementary to the miR-1/206 seed sequence (CATTCC). The conservation of these target sites in vertebrates was established by analyzing the 3′UTRs of the human and mouse paralogs for the presence of sites complementary to the miR-1/206 seed sequence.

mRNA and morpholino injection

mRNA was transcribed using the mMessage mMachine Kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer's instructions. For rSmoM2-eGFP overexpression, 100 pg rSmoM2-eGFP mRNA was injected into one-cell stage embryos. For the inhibition of miR-1 and miR-206, morpholinos (MOs) directed against the mature miRNA sequence (miR-1 MO and miR-206 MO) were designed and combined into a mix at a final concentration of 1 mM each. Unless otherwise noted, 1 nl of this mix was injected into one-cell stage embryos. As a control, 1 nl control MO at 1 mM was injected into one-cell embryos. A second set of MOs against miR-1 and miR-206 (miR-1 MO2 and miR-206 MO2) was also designed and injected as described above. All MOs against miR-1/206 have been used and validated previously as described in Mishima et al. (Mishima et al., 2009). Target protector MOs were designed to bind with perfect complementarity to 25 nt in the 3′UTR, including the miRNA seed sequence, for each of the miR-1/206 target sites in the vegfaa 3′UTR. Unless otherwise noted, 0.5 nl of a mix of these three target protectors at 1 mM each was injected in one-cell stage embryos. As a control, 1 nl of control MO at 1 mM was injected into one-cell embryos. All MOs were supplied by Gene Tools and dissolved in nuclease-free water. MO sequences are detailed in supplementary material Table S1.

Immunostaining

Embryos at 30 hours post-fertilization (hpf) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 2 hours, washed in PBS and transferred gradually to absolute methanol for overnight storage at −20°C. Embryos were then rehydrated in PBS-T (0.1% Tween 20 in PBS) and treated with proteinase K (10 μg/ml) for 15 minutes. This was followed by washes in PBS-T and fixation with 4% PFA for 15 minutes. The embryos were then washed with PBS-T, blocked in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in PBS-T for at least 1 hour at room temperature, and then incubated overnight in 200 μl of a solution of primary antibody against EGFP (rabbit; Molecular Probes) at 1:1000 dilution in 1% FBS in PBS-T at 4°C. Embryos were then washed four times in PBS-T for 30 minutes each at 4°C, then incubated overnight at 4°C in secondary anti-rabbit-Alexa 488 conjugate (mouse; Molecular Probes) at 1:1000 dilution in 1% FBS in PBS-T. Embryos were briefly washed in PBS-T, and DNA was stained with TO-PRO-3 (Molecular Probes) at 1:2000 dilution in PBS-T for 2 hours. Embryos were subsequently washed in PBS-T and cleared in 70% glycerol overnight at 4°C. Immediately before imaging, embryos were mounted in VECTASHIELD mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Images were taken with a Zeiss LSM 510 meta.

Calculation of vessel cross-sectional area

The cross-sectional vessel area was calculated from flattened confocal z-stacks taken with a Zeiss LSM 510 meta after immunostaining for EGFP as described above. Using Adobe Photoshop software, individual ISVs were traced and the area within the trace, in pixels, was normalized over the length of the vessel along the dorsoventral axis.

Calculation of the number of endothelial cells in a vessel

The number of endothelial cells in ISVs was manually determined from flattened confocal z-stacks taken with a Zeiss LSM 510 meta after immunostaining for GFP as described above.

Luciferase reporter constructs

The ORF of firefly luciferase (Fluc) was cloned between the BamHI-StuI sites of pCS2+ (pCS2 + Fluc) (Mishima et al., 2009). The vegfaa 3′UTR was amplified by RT-PCR from a cDNA library made from 0- to 36-hour embryos, and cloned into the XhoI-NotI sites of PCS2 + Fluc. Mutant luciferase reporters were constructed by amplifying the 3′UTR of vegfaa in fragments with an overlap in the mutant region. The mutation in the miR-1 target site (CATTCC to CTAACC) was included in the reverse primer of the 5′ fragment and the forward primer of the 3′ fragment. The full-length 3′UTR was obtained by PCR with the forward primer of the 5′ fragment and the reverse primer of the 3′ fragment in the presence of the 5′ and 3′ fragments as templates.

Target validation by luciferase assay

Zebrafish embryos were injected at the one-cell stage with 0.1 nl of a mix of firefly luciferase reporter mRNA and Renilla luciferase mRNA at 10 ng/μl each. Half of these embryos were then injected with 1 nl of miR-1 and miR-206 duplex at 5 μM each. miR-1 and miR-206 duplexes were acquired from Integrated DNA Technologies as siRNA duplex; sequences are given in supplementary material Table S1. At 9 hpf, ten embryos were collected and luciferase activity was assayed using the Dual-Glo Luciferase System (Promega) and a Modulus luminometer (Turner Biosystems) following the manufacturer's instructions. After subtracting background measurements, firefly luciferase activity intensity (IFluc) was normalized over Renilla luciferase activity (IRluc). The fold change expression of the reporter with and without the miRNA duplex was calculated as: (IFluc+miRNA/IRluc+miRNA)/(IFluc–miRNA/IRluc–miRNA). The luciferase ratio (IFluc–miRNA/IRluc–miRNA) was normalized to 100% in all figures. The assay was repeated at least three times for each reporter and the P-value was estimated by Student's t-test.

In situ hybridization

Antisense probes for the detection of vegfaa or vegfab were constructed by linearizing a pBluescript vector (Stratagene) containing the sequence of the vegfaa or vegfab ORF. After linearization, digoxigenin-labeled probes were transcribed in vitro with T7 RNA polymerase using a nucleotide mix containing DIG-dUTP (Roche). Probes were cleaned using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen). Embryos were fixed overnight in 4% PFA, then washed in PBS, and transferred gradually to absolute methanol for overnight storage at −20°C. In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (Mishima et al., 2009). Whenever multiple treatments are presented comparatively, the embryos were combined in the same tube to eliminate variability, following the procedures of Mishima et al. (Mishima et al., 2009). Prior to imaging, embryos stored in PFA were washed in PBS-T and transferred gradually to absolute methanol for overnight storage at −20°C. Immediately before imaging, they were placed in a 2:1 solution of benzyl benzoate:benzyl alcohol. Embryos were flat mounted in Permount (Fisher Scientific), and images were taken on a Zeiss Axio Imager M1. Modifications to the images taken were performed with Adobe Photoshop and kept constant across treatments compared.

Mosaic analysis

Mosaic analysis was performed using cell transplantation as described (Westerfield, 2000). For wild type to wild type (WT>WT) transplants, cells from Tg(fli-EGFP)y1 donors at sphere stage were transplanted into wild-type hosts at sphere stage and allowed to develop. For WT>miR-1/206MO transplants, cells from Tg(fli-EGFP)y1 donors at sphere stage were transplanted into sphere stage hosts injected at the one-cell stage with 1 nl of 1 mM miR-1/206 MO as described above. For control MO>WT transplants, Tg(fli-EGFP)y1 donors were injected at the one-cell stage with 1 nl of 1 mM control MO, and cells were transplanted at sphere stage into wild-type hosts at sphere stage and allowed to develop. For miR-1/206 MO>WT transplants, Tg(fli-EGFP)y1 donors were injected at the one-cell stage with 1 nl of 1 mM miR-1/206 MO, and cells were transplanted at sphere stage into wild-type hosts at sphere stage and allowed to develop. At ~30 hpf, the embryos were fixed and immunostained for EGFP, and the cross-sectional area of EGFP-positive vessels was measured using Adobe Photoshop.

Small molecule inhibition of VEGF signaling

The small molecule SU5416 (VEGFR2 kinase inhibitor III; Calbiochem) was prepared and utilized as described (Covassin et al., 2006). Briefly, SU5416 was dissolved to the indicated concentrations in Hank's medium (Westerfield, 2000), and embryos were placed in this solution from 18 hpf until ~30 hpf, when they were fixed for immunostaining as described above. Control embryos were treated with 0.1% DMSO.

Live imaging of vascular development

After injection of miR-1/206 MO or control MO as described above, time-lapse analyses were performed as described (Lawson and Weinstein, 2002) with the following modifications: Tg(fli:nGFP) embryos were mounted in 0.6% low-melt agarose dissolved in Hank's medium (Westerfield, 2000) at 18 hpf and imaged at 5-minute intervals until ~30 hpf. Imaging was performed using Nikon Ti-E Eclipse and Zeiss LSM510 Meta microscopes. The development of the vasculature was analyzed using Apple QuickTime software and annotated using Adobe Photoshop.

Northern blot

RNA extraction and northern blot to detect miR-1/206 in cell line extracts were performed as described previously (Cifuentes et al., 2010). The miRNAs were detected using a mix of DNA oligonucleotide probes complementary to miR-1 and miR-206 labeled with [α32P]dATP by the StarFire method (Integrated DNA Technologies) following the manufacturer's instructions. Loading was controlled using a similarly labeled probe against 5S rRNA.

Cell culture

Human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from the Tissue Culture Core Laboratory of the Vascular Biology and Therapeutics Program (Yale University) and serially cultured on 0.1% gelatin-coated flasks in M199/20% FBS supplemented with l-glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) and endothelial cell growth supplement (ECGS; BD Biosciences), with heparin from porcine intestines as described (Suárez et al., 2007). HT-1080 human fibrosarcoma cells and RD human rhabdomyosarcoma cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured as indicated.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the miRNeasy Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For mRNA quantification, cDNA was synthesized using TaqMan RT reagents (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in triplicate using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad) and the Mastercycler Realplex (Eppendorf) system. The mRNA level was normalized to gapdh as a housekeeping gene. For miRNA quantification, total RNA was reverse transcribed using the RT2 miRNA First Strand Kit (SABiosciences). Primers specific for human MIR1 and MIR206 (SABiosciences) were used and values normalized to human SNORD38B.

ELISA

Supernatants collected from cells growing exponentially for 36 hours were assayed using an ELISA kit for VEGF (Peprotech) following the manufacturers' instructions. VEGF secretion was normalized by protein concentration.

Western blot analysis

Samples were prepared as described (Suárez et al., 2007; Chamorro-Jorganes et al., 2011). Briefly, cells were lysed in ice-cold buffer comprising 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 125 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 5.3 mM NaF, 1.5 mM Na3PO4, 1 mM orthovanadate, 175 mg/ml octylglucopyranoside, 1 mg/ml protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 0.25 mg/ml AEBSF (Roche). Cell lysates were rotated at 4°C for 1 hour before the insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 g for 10 minutes. After normalizing for equal protein concentration, cell lysates were resuspended in SDS sample buffer before separation by SDS-PAGE. Western blots were performed using rabbit polyclonal antibodies against VEGF (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and mouse monoclonal HSP-90 antibody (1:3000; BD Biosciences). Protein bands were visualized using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biotechnology).

Cord formation assay

HUVECs (7×104) were cultured in a 24-well plate coated with 200 μl growth factor reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences) as described (Suárez et al., 2007; Chamorro-Jorganes et al., 2011). HUVECs were plated in HUVEC culture medium (M199) with or without FBS and ECGS as positive and negative control, respectively, in M199 medium supplemented with 100 ng/ml recombinant VEGF (R&D Systems), or in M199 conditioned medium from HT-1080 and RD cells that were growing exponentially for 36 hours. In some instances, conditioned medium was incubated with 5 μg/ml VEGF blocking antibody (AF-293-NA; R&D Systems). HUVECs were also plated in conditioned media from RD cells transfected with inhibitors of miR-1 and miR-206, as indicated below. Sprout length of capillary-like structures was imaged with an Axiovert microscope (Carl Zeiss) and the cumulative tube length was measured in three fields for each replicate, per experiment.

miRNA transfection

RD cells were transfected with 60 nM antagomir miRNA inhibitors (anti-miR-1/206; Dharmacon) utilizing Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) as previously described (Suárez et al., 2007; Chamorro-Jorganes et al., 2011). Experimental control samples were treated with an equal concentration of inhibitor negative control sequence. The efficiency of transfection was greater than 95%, as assessed by transfection with fluorescently labeled miRIDIAN miRNA mimic (miRNAmimic-Alexa Fluor 555; Dharmacon) and visualization by fluorescence microscopy 12 hours after transfection. After three consecutive rounds of transfection, the conditioned medium was used for cord formation experiments.

RESULTS

miR-1/206 regulate angiogenesis during development

miR-1 and miR-206 are evolutionarily conserved, have common expression patterns in the muscle (Wienholds et al., 2005; Mishima et al., 2009), and share a large part of their sequence (18 of 22 nt, including the seed region; supplementary material Fig. S1). To investigate whether miRNAs regulate the cross-talk between the muscle and surrounding tissues during developmental angiogenesis, we analyzed the effect of blocking miR-1 and miR-206 function on the vasculature. We injected one-cell stage zebrafish embryos with either a control MO or a mixture of two antisense MOs that target miR-1 and miR-206 (hereafter referred to as miR-1/206 MO (Mishima et al., 2009) (supplementary material Fig. S1), and analyzed vascular development using a transgenic line that labels endothelial cells: Tg(fli-EGFP)y1 (Lawson and Weinstein, 2002).

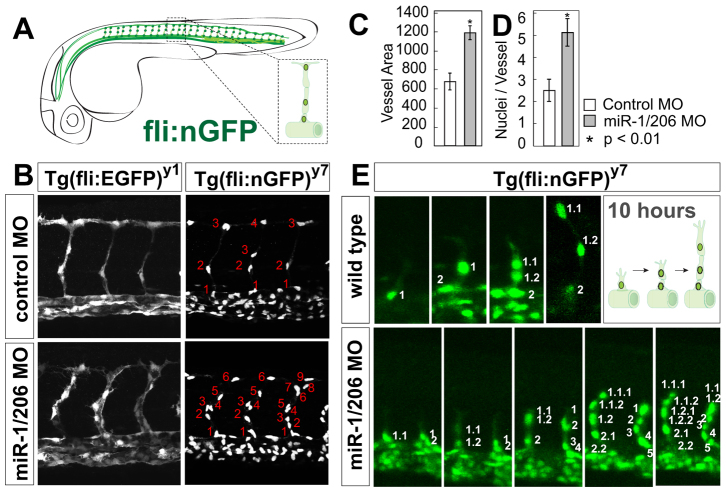

In Tg(fli-EGFP)y1 fish injected with control MO and wild-type embryos, endothelial cells sprout from the dorsal aorta to form the intersegmental vessels (ISVs), which migrate along the intersomitic space and connect atop the somite to form the dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessel (DLAV) at 30 hpf (Fig. 1A) (Childs et al., 2002; Lawson et al., 2002). Embryos injected with miR-1/206 MO display larger ISVs (increased cross-sectional area) than wild-type embryos (Fig. 1B,C). This effect is accompanied by a significant increase in the number of endothelial cells, as labeled by Tg(fli-nuclearGFP)y7 (Roman et al., 2002), relative to controls (from 3-4 cells in control MO to 6-9 cells in miR-1/206 MO; Fig. 1B,D). This phenotype is specific to miR-1/206 downregulation, as it could be recapitulated by injecting a second set of non-overlapping MOs against miR-1 and miR-206 (supplementary material Fig. S1). Live imaging analysis of control and miR-1/206 MO-injected Tg(fli-nGFP)y7 embryos revealed that this increase in cell number is a consequence of enhanced endothelial cell migration as well as elevated cell proliferation once endothelial cells enter the intersomitic region (Fig. 1E). Together, these results indicate that miR-1/206 play an important anti-angiogenic role in the development of the intersegmental vasculature.

Fig. 1.

miR-1 and miR-206 regulate developmental angiogenesis. (A) Schematic representation of the zebrafish vasculature. The intersegmental vessels (ISVs) form by sprouting endothelial cells from the dorsal aorta and are typically composed by three cells: the tip, the stalk, and the basal cell that connects to the aorta (inset). (B) ISVs labeled with cytoplasmic GFP [Tg(fli-EGFP)y1] or nuclear GFP [Tg(fli-nGFP)y7] after injection of control morpholino (MO) or miR-1/206 MO at the one-cell stage. (C,D) Quantification of the cross-sectional area (C) and average number of nuclei per ISV (D) in control MO-injected and miR-1/206 MO-injected embryos at 30 hpf. Note the increase in ISV size (cross-sectional area) and number of endothelial cells in embryos injected with miR-1/206 MO compared with control MO-injected embryos. Mean ± s.d.; Student's t-test. (E) Individual frames of a time-lapse confocal analysis of the vascular phenotype in wild-type and miR-1/206 MO-injected embryos between 18 and 28 hpf. Endothelial cells migrating into the vessel are numbered (1, 2, 3, etc.) and their daughter cells are labeled (1.1, 1.2, 1.2.1, etc.). The wild-type ISV shows a highly stereotyped pattern, in which a single endothelial cell migrates to the trunk midline and divides, leaving one cell stationary while the tip cell continues to migrate dorsally. Endothelial cells in miR-1/206 MO-injected embryos show elevated proliferation within the ISV (left vessel), as well as an increase in migration from the aorta (right vessel).

Consistent with the expression of miR-1/206 in the muscle, mosaic analysis supports a non-cell-autonomous effect of miR-1/206 in the vasculature (supplementary material Fig. S2). First, increased vessel size was observed when host embryos were deficient in miR-1/206 function (miR-1/206 MO), but not in control MO-injected embryos (supplementary material Fig. S2A,B). Second, ISVs formed by endothelial cells derived from a miR-1/206 MO-injected donor display a wild-type phenotype when transplanted into wild-type hosts (miR-1/206 MO>WT) (supplementary material Fig. S2C,D), indicating that the phenotype observed in the intersomitic vessels is independent of the genotype of the endothelial donor cells. These results support a role for miR-1/206 in the regulation of a pro-angiogenic factor that is non-autonomous to endothelial cells.

miR-1/206 regulate the expression of vegfaa

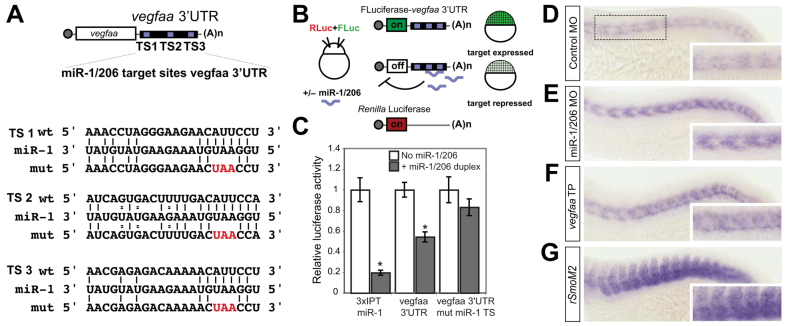

Several signals from the muscle are known to regulate vessel growth and patterning. VEGF promotes the differentiation of endothelial progenitors and stimulates endothelial cell growth, survival and migration (Carmeliet and Jain, 2011; Ferrara et al., 2003). By contrast, Semaphorin-Plexin D1 signaling represses angiogenic potential by antagonizing Vegf function and ensures proper guidance of intersomitic sprouts (Torres-Vázquez et al., 2004; Zygmunt et al., 2011). To determine whether these systems are regulated by miR-1/206, we analyzed the 3′UTRs of candidate genes in each pathway for putative miR-1/206 target sites. Furthermore, we reasoned that the target responsible for the miR-1/206 loss-of-function phenotype should be expressed in muscle at developmental stages consistent with ISV development (18-30 hpf). Through this combined approach, we found that zebrafish vegfaa contains three miR-1/206 target sites in its 3′UTR (Fig. 2A). The presence of these target sites is maintained across species, including humans, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved function (supplementary material Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

miR-1/206 regulate the expression of vegfaa. (A) The zebrafish vegfaa 3′UTR, indicating the sequence of each miR-1/206 target site (TS1-3), the alignment of each TS with miR-1, and the sequence of the mutant reporter in which the seed sequence complementary to miR-1/206 has been mutated from ACAUUCCU to ACUAACCU (mut). (B) The luciferase assay to test the functionality of the TS in the vegfaa 3′UTR. Embryos were co-injected with a firefly luciferase reporter containing the 3′UTR of vegfaa and a control Renilla luciferase reporter, in the presence (+) or absence of miR-1 and miR-206 duplex miRNA. (C) The TSs in vegfaa are functional and necessary for miR-1/206-mediated repression. miR-1/206 downregulate the luciferase activity expressed from the luciferase-vegfaa 3′UTR reporter (vegfaa 3′UTR) compared with the Renilla control. A luciferase reporter construct containing a 3′UTR with mutated miR-1/206 TS (vegfaa 3′UTR mut miR-1 TS) is not significantly repressed by the miR-1/206 duplex. As a positive control for repression, a luciferase reporter containing three partially complementary TSs for miR-1/206 (3×IPT miR-1) was downregulated in the presence of miR-1/206 duplex. Mean ± s.d.; *P<0.01, Student's t-test. (D-G) In situ hybridization to detect vegfaa expression at 24 hpf in embryos injected at the one-cell stage with control MO (D), miR-1/206 MO (E), vegfaa-TPmiR-1 (F) or dominant-active rat Smo mRNA (rSmoM2) (G). Note that blocking miR-1/206 function with miR-1/206 MO (E), miR-1/206 activity on vegfaa using target protectors (F), or upregulating the Shh pathway (G) increases the levels of vegfaa mRNA.

To determine whether miR-1/206 regulate the 3′UTR of vegfaa, we analyzed the expression of a firefly luciferase reporter containing the vegfaa 3′UTR, relative to a Renilla luciferase control, in the presence or absence of miR-1/206 duplex (Fig. 2B). The luciferase activity of the wild-type vegfaa reporter was significantly repressed by miR-1/206 (Fig. 2C). Regulation of the vegfaa reporter depended on the presence of miR-1/206 target sites, as a reporter in which these target sites were mutated (CATTCC to CTAACC; vegfaa mut 3′UTR) failed to be repressed by miR-1/206 (Fig. 2C).

Having established the functionality of the miR-1/206 target sites in the 3′UTR of vegfaa, we examined whether vegfaa is regulated in vivo by these miRNAs. Because vegfaa is also expressed in other domains besides the muscle, quantification of the effect of miR-1/206 on the endogenous transcript is impaired by the contribution of other tissues. Thus, to determine both the degree and spatial domain of the regulation of vegfaa, we directly visualized the levels of vegfaa mRNA by in situ hybridization with a probe directed to the coding region of the gene. We found that vegfaa levels in the somites were upregulated in 22-hpf embryos injected with miR-1/206 MO relative to controls, consistent with the loss of a negative regulatory factor (Fig. 2D,E). Together, these results indicate that miR-1/206 can regulate vegfaa expression during development.

The increase in angiogenesis observed in miR-1/206 knockdown depends on Vegf activity

Our results indicate that miR-1/206 regulate the 3′UTR of vegfaa. To test whether the increase in endothelial cells upon miR-1/206 knockdown (KD) was caused by the misregulation of vegfaa, we examined whether increasing the levels of VegfAa can recapitulate this phenotype. We attempted to overexpress vegfaa using mRNA injection at the one-cell stage; however, this led to developmental defects in the early embryo. To overcome this limitation, we activated the Sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathway, which is responsible for the expression of endogenous vegfaa in the somites (Lawson et al., 2002). Expression of rSmoM2, a constitutively active allele of rat Smo (Huang and Schier, 2009) that activates Shh signaling, resulted in enhanced vegfaa expression in the somites (Fig. 2G), accompanied by an increase in the number of endothelial cells composing the ISV (supplementary material Fig. S4A-C). This phenotype is dependent on VegfAa overexpression because reducing VegfAa expression by means of an AUG MO rescued the phenotype (supplementary material Fig. S4A,B). To confirm that the miR-1/206 MO phenotype does not arise due to activation of Hedgehog (Hh) signaling rather than the direct regulation of vegfaa, we examined the expression of another target of the Hh pathway, engrailed (eng) (Degenhardt and Sassoon, 2001; Fjose et al., 1992; Wolff et al., 2003), when miR-1/206 function was blocked. The domain and intensity of Eng expression were similar between wild type and miR-1/206 morphants (supplementary material Fig. S4D), indicating that blocking miR-1/206 function promotes ISV angiogenesis downstream of Hh signaling.

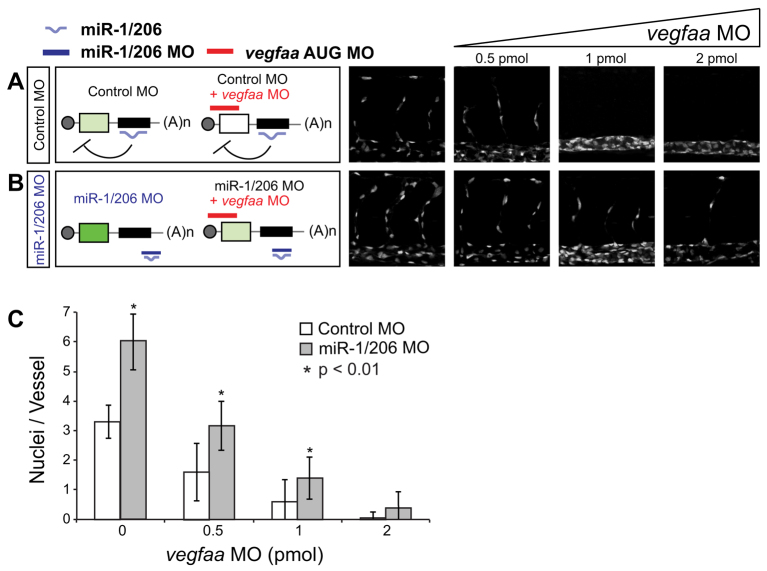

We reasoned that if the increase in angiogenesis observed in miR-1/206 KD is due to VegfAa misregulation, reducing the levels of VegfAa signaling would rescue this phenotype. To test this, we used two alternative approaches. First, we employed SU5416, a selective inhibitor of the VEGF receptor Kdrl (also known as VEGFR2, Flk1), to block Vegf signaling (Fong et al., 1999). We found that increasing concentrations of SU5416 (0.2 μM to 0.4 μM) rescued the angiogenesis phenotype of miR-1/206 morphants (supplementary material Fig. S5), suggesting that miR-1/206 are likely to function upstream of the Vegf receptor. Second, reducing the levels of VegfAa with a translation-blocking AUG MO (vegfaa MO) rescued the miR-1/206 KD vascular phenotype (Fig. 3A,B; supplementary material Fig. S6). By contrast, reducing the levels of the zebrafish paralog VegfAb did not affect the ISV phenotype (supplementary material Fig. S7), consistent with its predominant expression in the anterior region of the embryo. Together, these results indicate that the phenotype observed when blocking miR-1/206 function is dependent on VegfAa activity, consistent with the proposed role of miR-1/206 in the regulation of vegfaa during angiogenesis.

Fig. 3.

Reducing translation of vegfaa rescues the increase in angiogenesis caused by miR-1/206 loss of function. (A,B) Tg(fli-nGFP)y7 zebrafish embryos injected at the one-cell stage with control MO (A) or miR-1/206 MO (B) were also injected with increasing concentrations of a translation-blocking AUG MO against vegfaa (vegfaa MO). Increasing amounts of vegfaa MO reduced ISV formation and rescued the phenotypes observed when blocking miR-1/206 function (B). (C) Quantification of the average number of nuclei per ISV in control MO-injected and miR-1/206 MO-injected embryos co-injected with increasing concentrations of vegfaa MO at 30 hpf. Mean ± s.d.; Student's t-test.

miR-1/206-mediated regulation of endogenous vegfaa is required to modulate angiogenesis

miRNAs are widespread regulators of gene expression, and it is predicted that each miRNA has the potential to regulate several hundred target mRNAs (Bartel, 2009). Thus, a fundamental challenge in the field is to identify whether regulation of a putative target by an miRNA is physiologically relevant (Choi et al., 2007; Staton and Giraldez, 2011). We have shown that reducing the levels of VegfAa or reducing the levels of signaling after SU5416 treatment suppresses the increase in angiogenesis observed when miR-1/206 function is blocked. These results are consistent with the proposed role of miR-1/206 in the regulation of vegfaa; however, they do not rule out the possibility that the suppression is due to the essential role of Vegf in angiogenesis.

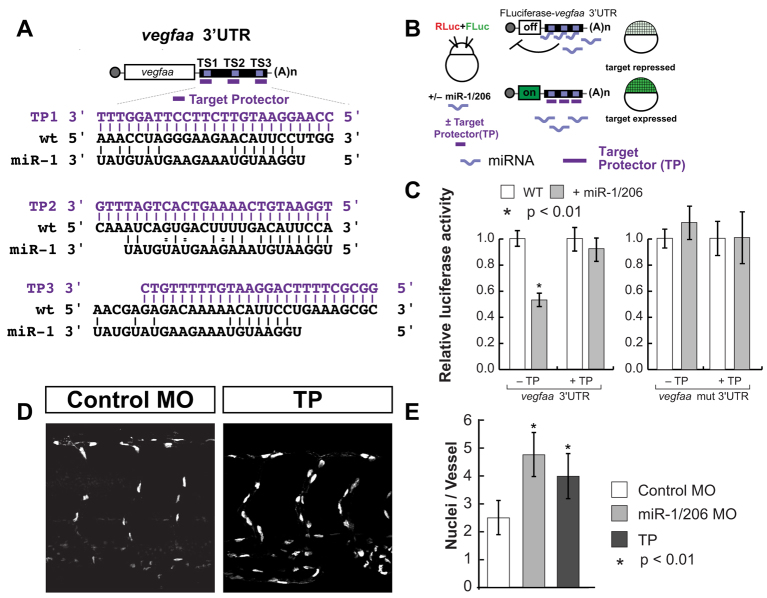

To directly address the interaction of miR-1/206 with vegfaa in vivo, we employed target protectors (TPs), which are MOs complementary to the miRNA target sites in a 3′UTR (Choi et al., 2007; Staton and Giraldez, 2011). By binding to specific target sites, they compete with the miRNA for binding to the target and block miRNA-mediated repression of a specific mRNA without affecting other targets. We have previously established that TPs that bind outside the target sites do not have any effect in the regulation of the target mRNA, and that their function is specific for the target designed (Staton and Giraldez, 2011; Choi et al., 2007; Staton et al., 2011). To specifically modulate the interaction of miR-1/206 with vegfaa in vivo, we designed TPs for each of the miR-1/206 target sites in vegfaa (vegf-TPmiR-1) (Fig. 4A). We tested the ability of vegf-TPmiR-1 to block repression of a luciferase reporter mRNA by miR-1/206 (Fig. 4B,C). Co-injection of the luciferase-vegfaa 3′UTR reporter with vegf-TPmiR-1 restored luciferase expression to a level similar to that of the mutant reporter; however, expression of the mutant reporter was unaffected by vegf-TPmiR-1 (Fig. 4C), suggesting that expression of targets with three or more mismatches to the TP are not affected by these TPs. These results indicate that the TPs used are specific and efficient in reducing miR-1/206-mediated repression of vegfaa.

Fig. 4.

Target protectors relieve miR-1/206-mediated repression of the vegfaa 3′UTR. (A) Sequence of each target site, the cognate target protector (TP, violet) and miR-1. (B) Luciferase assay to test the action of vegfaa TP as described in Fig. 2. (C) Luciferase reporter assay to determine the ability of the TPs to prevent miR-1/206-mediated repression of the luciferase-vegfaa 3′UTR. Repression of the luciferase-vegfaa 3′UTR is relieved in the presence of vegfaa TPs (+TP). (D) Confocal analysis of GFP expression in the ISV of Tg(fli-nGFP)y7 zebrafish embryos injected with control MO or vegf-TPmiR-1 at the one-cell stage. (E) Quantitation of the number of nuclei per ISV of control MO-, miR-1/206 MO- or TP-injected embryos. Note the increase in endothelial cells in the ISV of embryos injected with TP against the miR-1/206 target sites in the vegfaa 3′UTR. (C,E) Mean ± s.d.; Student's t-test.

To test the effect of these TPs in vivo, we injected them into Tg(fli-nGFP)y7 zebrafish embryos and monitored intersomitic vessel development. First, we assayed the expression of vegfaa in TP-injected embryos by in situ hybridization. We found that vegfaa mRNA levels are elevated in the somites relative to controls (Fig. 2F), similar to miR-1/206 KD embryos. Second, protection of the miR-1/206 target sites in vegfaa had a pro-angiogenic effect, resulting in intersomitic vessels with elevated numbers of endothelial cells compared with controls (Fig. 4D,E). This phenotype recapitulated the vascular defect observed when miR-1/206 function was blocked. These results indicate (1) that despite the large number of miR-1/206 targets, the miR-1/206 KD phenotype is at least in part a result of altered vegfaa regulation and (2) that miR-1/206 directly regulate the levels of vegfaa to modulate angiogenesis during development.

DISCUSSION

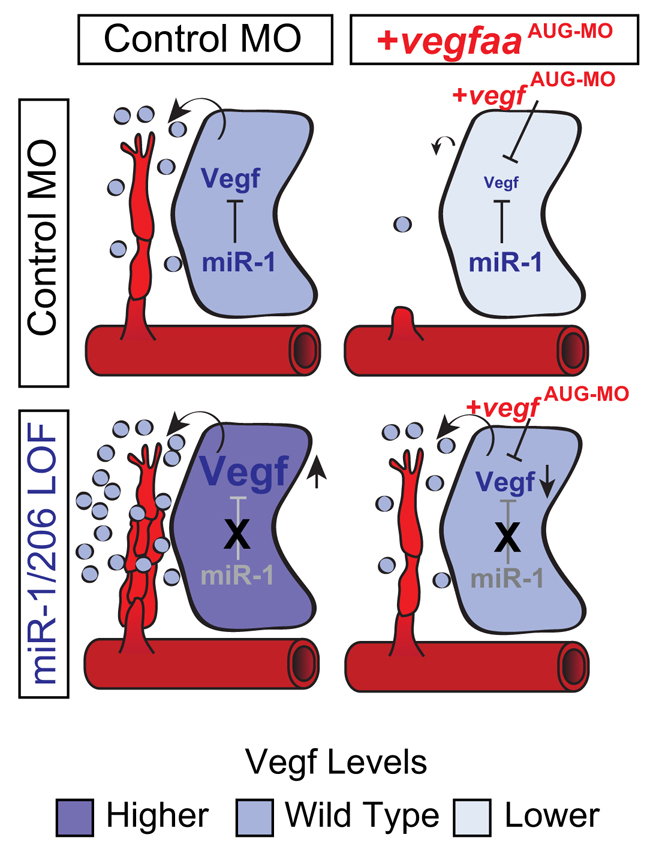

Our study shows that miR-1/206 negatively regulate angiogenesis during zebrafish development. Because miRNAs have hundreds of putative targets, it is challenging to determine the physiological function of individual miRNA-target interactions. Using TPs and MO KD, we show that miR-1/206 regulate angiogenesis by modulating the levels of the potent angiogenic factor VegfA. Taken together, our findings identify a novel regulatory layer that modulates the cross-talk between muscle and vasculature during developmental angiogenesis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Model for the role of miR-1/206 in developmental angiogenesis. In the somites, miR-1/206 target vegfaa for regulation through target sites in its 3′UTR. This modulation ensures that the production of VegfAa by the somites is maintained at the optimal level to promote ISV angiogenesis. Preventing this miRNA-mediated regulatory system from acting on vegfaa [miR-1/206 loss of function (LOF)] results in excess VegfAa production and enhanced ISV angiogenesis. Importantly, the angiogenic effect derived from elevated vegfaa expression can be rescued by co-treatment with a translation-blocking vegfaa MO, which reduces VegfAa signaling to endogenous levels.

VegfA plays a central role in the stimulation and control of angiogenesis, requiring it be tightly regulated during embryonic development and homeostasis. This modulation occurs both in the signaling and the receiving cells (Carmeliet and Jain, 2011). Several regulatory layers control the activity of the pathway in endothelial cells: (1) the Notch-Delta pathway limits the response to Vegf to the tip cells of developing vessels, thereby regulating the number of cells that respond to Vegf signaling (Siekmann et al., 2008); (2) the class 3 semaphorins compete with VegfA for binding to, and activation of, Neuropilins, limiting the angiogenic effects of VegfA in providing guidance cues to migrating vessels (Staton et al., 2007); (3) Semaphorin-Plexin signaling acts to maintain the endothelial expression of the inhibitory VegfA receptor soluble flt1 (sflt1) (Zygmunt et al., 2011), lessening the intensity of the signal around endothelial cells; and (4) miR-126 plays an active role in potentiating the Vegf signal in endothelial cells by targeting spred1 and pik3r2 (Fish et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008), two negative regulators of Vegf signaling.

These mechanisms govern the sensitivity and response to Vegf signaling in the receiving cells, but less is known about the regulatory systems that control Vegf production during development. Our findings indicate that vegfaa is targeted by miR-1/206 in the muscle to modulate the expression of the ligand, allowing the organism to regulate this signaling pathway. Indeed, this regulation seems to be conserved in other biological systems, as blocking miR-1/206 function affects VEGF expression and the angiogenic activity of mammalian cell lines in vitro (supplementary material Fig. S8). This effect of miR-1/206 contrasts with the pro-angiogenic role of miR-206 during muscle regeneration in rats (Nakasa et al., 2010), yet no effect in angiogenesis has been observed in muscle-injured Mir206 knockout mice (Liu et al., 2012). The difference in these results might be due to the system under study or the context of embryonic development versus the muscle injury model, and future studies will be required to address these differences. It is known that the VEGFA 3′UTR contains elements that stabilize the mRNA, including the hypoxia stability region, as well as inhibitory elements such as that targeted by the IFN-γ-activated inhibitor of translation complex (GAIT) (Ray et al., 2009). Therefore, miR-1/206 are likely to act within a complex regulatory system to control VegfA production. Together, these regulatory mechanisms provide flexibility to modulate angiogenesis not only during development, but also during states such as hypoxia or ischemia.

Cross-tissue communication often relies upon potent secreted molecules such as chemokines, TGFs, WNTs, Shh and FGFs (Müller and Schier, 2011; Rogers and Schier, 2011). These are potent signaling molecules that function in a concentration-dependent manner to elicit specific effects. Tight regulation of the ligand is therefore essential to achieve the appropriate response and avoid saturation of the pathway. Indeed, it has been established that even moderate fluctuations in the levels of VEGF can have detrimental effects on vasculature development and homeostasis. For example, heterozygous loss of a wild-type VEGF allele causes a severe haploinsufficient phenotype (Carmeliet et al., 1996), resulting in developmental defects in the vascular network and embryonic lethality. We propose that the identification of miRNA-mediated regulation of potent signaling molecules such as TGFβ (Choi et al., 2007; Martello et al., 2007; Rosa et al., 2009), chemokine ligands (Staton et al., 2011) and Vegf (this study) (Hua et al., 2006; Long et al., 2010) reveals a common theme whereby miRNA-mediated regulatory interactions allow the cell to modulate the levels of signaling, provide robustness to the system and facilitate the dynamic regulation of gene expression.

The identification of miR-1/206-mediated regulation of Vegf might be significant beyond developmental angiogenesis. A pivotal step in solid tumor progression and metastasis is the invasion or co-option of capillaries, which provide growing tumors with oxygen and nutrients required by their elevated metabolic activity (Carmeliet and Jain, 2011; Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). As in developmental angiogenesis, VEGF signaling is an essential component of the angiogenic response of a wide variety of tumors, making it a prime clinical target for the development of therapeutic agents (Carmeliet and Jain, 2011; Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). It has also become clear that miRNAs can play important roles in the development and growth of tumors, often by targeting key components of potent signaling cascades that control proliferation and survival. However, a role for miRNAs in pathogenic angiogenesis has only recently been considered (Small and Olson, 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). Our findings indicate that altering the levels of miR-1 and miR-206 can affect the levels of angiogenesis in vivo through the modulation of VegfAa. Future studies will be required to understand whether the regulation of VEGF by miRNAs plays an important role in angiogenesis during human disease and cancer.

Acknowledgements

We thank Suk-Won Jin, Jesus Torres-Vazquez and Michael Parsons for zebrafish lines; Jym Ocbina, Stefania Nicoli and Nathan Lawson for critical reading of the manuscript and analysis of the angiogenic potential of tumor cells in zebrafish embryos; members of the A.J.G. laboratory for helpful discussions; and H. Patnode for fish husbandry.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by the Pew Scholars Program in the Biomedical Sciences, the Yale Scholar Program, the Muscular Dystrophy Association and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants [R01GM081602-05] to A.J.G.; by a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad and Grants in Aid for Young Scientist to Y.M.; The Uehara Memorial Foundation and The NOVARTIS Foundation (Japan) for the Promotion of Science [Y.M.]; and a Scientist Development Grant-American Heart Association [0835481N] and NIH grant [R01HL105945] from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to Y.S. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.083774/-/DC1

References

- Bartel D. P. (2009). MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136, 215-233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutz P. L., Chawla G., Stoilov P., Black D. L. (2007). MicroRNAs regulate the expression of the alternative splicing factor nPTB during muscle development. Genes Dev. 21, 71-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Cao R., Hedlund E. M. (2008). Regulation of tumor angiogenesis and metastasis by FGF and PDGF signaling pathways. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 86, 785-789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporali A., Emanueli C. (2011). MicroRNA regulation in angiogenesis. Vascul. Pharmacol. 55, 79-86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P., Jain R. K. (2011). Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 473, 298-307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P., Ferreira V., Breier G., Pollefeyt S., Kieckens L., Gertsenstein M., Fahrig M., Vandenhoeck A., Harpal K., Eberhardt C., et al. (1996). Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature 380, 435-439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro-Jorganes A., Araldi E., Penalva L. O., Sandhu D., Fernández-Hernando C., Suárez Y. (2011). MicroRNA-16 and microRNA-424 regulate cell-autonomous angiogenic functions in endothelial cells via targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and fibroblast growth factor receptor-1. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31, 2595-2606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs S., Chen J. N., Garrity D. M., Fishman M. C. (2002). Patterning of angiogenesis in the zebrafish embryo. Development 129, 973-982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi W. Y., Giraldez A. J., Schier A. F. (2007). Target protectors reveal dampening and balancing of Nodal agonist and antagonist by miR-430. Science 318, 271-274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung A. S., Ferrara N. (2011). Developmental and pathological angiogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 27, 563-584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciais D., Cherradi N., Bailly S., Grenier E., Berra E., Pouyssegur J., Lamarre J., Feige J. J. (2004). Destabilization of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA by the zinc-finger protein TIS11b. Oncogene 23, 8673-8680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes D., Xue H., Taylor D. W., Patnode H., Mishima Y., Cheloufi S., Ma E., Mane S., Hannon G. J., Lawson N. D., et al. (2010). A novel miRNA processing pathway independent of Dicer requires Argonaute2 catalytic activity. Science 328, 1694-1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claffey K. P., Shih S. C., Mullen A., Dziennis S., Cusick J. L., Abrams K. R., Lee S. W., Detmar M. (1998). Identification of a human VPF/VEGF 3′ untranslated region mediating hypoxia-induced mRNA stability. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 469-481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covassin L. D., Villefranc J. A., Kacergis M. C., Weinstein B. M., Lawson N. D. (2006). Distinct genetic interactions between multiple Vegf receptors are required for development of different blood vessel types in zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 6554-6559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt K., Sassoon D. A. (2001). A role for Engrailed-2 in determination of skeletal muscle physiologic properties. Dev. Biol. 231, 175-189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibbens J. A., Polyak S. W., Damert A., Risau W., Vadas M. A., Goodall G. J. (2001). Nucleotide sequence of the mouse VEGF 3′UTR and quantitative analysis of sites of polyadenylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1518, 57-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djuranovic S., Nahvi A., Green R. (2011). A parsimonious model for gene regulation by miRNAs. Science 331, 550-553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian M. R., Sonenberg N., Filipowicz W. (2010). Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 351-379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N., Gerber H. P., LeCouter J. (2003). The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat. Med. 9, 669-676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish J. E., Santoro M. M., Morton S. U., Yu S., Yeh R. F., Wythe J. D., Ivey K. N., Bruneau B. G., Stainier D. Y., Srivastava D. (2008). miR-126 regulates angiogenic signaling and vascular integrity. Dev. Cell 15, 272-284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjose A., Njølstad P. R., Nornes S., Molven A., Krauss S. (1992). Structure and early embryonic expression of the zebrafish engrailed-2 gene. Mech. Dev. 39, 51-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong T. A., Shawver L. K., Sun L., Tang C., App H., Powell T. J., Kim Y. H., Schreck R., Wang X., Risau W., et al. (1999). SU5416 is a potent and selective inhibitor of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (Flk-1/KDR) that inhibits tyrosine kinase catalysis, tumor vascularization, and growth of multiple tumor types. Cancer Res. 59, 99-106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe J. A., Jiang B. H., Iyer N. V., Agani F., Leung S. W., Koos R. D., Semenza G. L. (1996). Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 4604-4613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman R. C., Farh K. K., Burge C. B., Bartel D. P. (2009). Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 19, 92-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D., Weinberg R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646-674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper S. J., Bates D. O. (2008). VEGF-A splicing: the key to anti-angiogenic therapeutics? Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 880-887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Z., Lv Q., Ye W., Wong C. K., Cai G., Gu D., Ji Y., Zhao C., Wang J., Yang B. B., et al. (2006). MiRNA-directed regulation of VEGF and other angiogenic factors under hypoxia. PLoS ONE 1, e116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P., Schier A. F. (2009). Dampened Hedgehog signaling but normal Wnt signaling in zebrafish without cilia. Development 136, 3089-3098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntzinger E., Izaurralde E. (2011). Gene silencing by microRNAs: contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 99-110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafarifar F., Yao P., Eswarappa S. M., Fox P. L. (2011). Repression of VEGFA by CA-rich element-binding microRNAs is modulated by hnRNP L. EMBO J. 30, 1324-1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King I. N., Qian L., Liang J., Huang Y., Shieh J. T., Kwon C., Srivastava D. (2011). A genome-wide screen reveals a role for microRNA-1 in modulating cardiac cell polarity. Dev. Cell 20, 497-510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M., Rauhut R., Lendeckel W., Tuschl T. (2001). Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science 294, 853-858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M., Rauhut R., Yalcin A., Meyer J., Lendeckel W., Tuschl T. (2002). Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr. Biol. 12, 735-739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson N. D., Weinstein B. M. (2002). In vivo imaging of embryonic vascular development using transgenic zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 248, 307-318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson N. D., Vogel A. M., Weinstein B. M. (2002). sonic hedgehog and vascular endothelial growth factor act upstream of the Notch pathway during arterial endothelial differentiation. Dev. Cell 3, 127-136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy N. S., Chung S., Furneaux H., Levy A. P. (1998). Hypoxic stabilization of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA by the RNA-binding protein HuR. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6417-6423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Williams A. H., Maxeiner J. M., Bezprozvannaya S., Shelton J. M., Richardson J. A., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N. (2012). microRNA-206 promotes skeletal muscle regeneration and delays progression of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 2054-2065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J., Wang Y., Wang W., Chang B. H., Danesh F. R. (2010). Identification of microRNA-93 as a novel regulator of vascular endothelial growth factor in hyperglycemic conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 23457-23465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Getz G., Miska E. A., Alvarez-Saavedra E., Lamb J., Peck D., Sweet-Cordero A., Ebert B. L., Mak R. H., Ferrando A. A., et al. (2005). MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature 435, 834-838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martello G., Zacchigna L., Inui M., Montagner M., Adorno M., Mamidi A., Morsut L., Soligo S., Tran U., Dupont S., et al. (2007). MicroRNA control of Nodal signalling. Nature 449, 183-188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima Y., Abreu-Goodger C., Staton A. A., Stahlhut C., Shou C., Cheng C., Gerstein M., Enright A. J., Giraldez A. J. (2009). Zebrafish miR-1 and miR-133 shape muscle gene expression and regulate sarcomeric actin organization. Genes Dev. 23, 619-632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller P., Schier A. F. (2011). Extracellular movement of signaling molecules. Dev. Cell 21, 145-158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakasa T., Ishikawa M., Shi M., Shibuya H., Adachi N., Ochi M. (2010). Acceleration of muscle regeneration by local injection of muscle-specific microRNAs in rat skeletal muscle injury model. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 14, 2495-2505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onesto C., Berra E., Grépin R., Pagès G. (2004). Poly(A)-binding protein-interacting protein 2, a strong regulator of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34217-34226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajewsky N. (2006). microRNA target predictions in animals. Nat. Genet. 38 Suppl., S8-S13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray P. S., Fox P. L. (2007). A post-transcriptional pathway represses monocyte VEGF-A expression and angiogenic activity. EMBO J. 26, 3360-3372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray P. S., Jia J., Yao P., Majumder M., Hatzoglou M., Fox P. L. (2009). A stress-responsive RNA switch regulates VEGFA expression. Nature 457, 915-919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K. W., Schier A. F. (2011). Morphogen gradients: from generation to interpretation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 27, 377-407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman B. L., Pham V. N., Lawson N. D., Kulik M., Childs S., Lekven A. C., Garrity D. M., Moon R. T., Fishman M. C., Lechleider R. J., et al. (2002). Disruption of acvrl1 increases endothelial cell number in zebrafish cranial vessels. Development 129, 3009-3019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa A., Spagnoli F. M., Brivanlou A. H. (2009). The miR-430/427/302 family controls mesendodermal fate specification via species-specific target selection. Dev. Cell 16, 517-527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siekmann A. F., Covassin L., Lawson N. D. (2008). Modulation of VEGF signalling output by the Notch pathway. BioEssays 30, 303-313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small E. M., Olson E. N. (2011). Pervasive roles of microRNAs in cardiovascular biology. Nature 469, 336-342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol N. S., Ambros V. (2005). Mesodermally expressed Drosophila microRNA-1 is regulated by Twist and is required in muscles during larval growth. Genes Dev. 19, 2343-2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton A. A., Giraldez A. J. (2011). Use of target protector morpholinos to analyze the physiological roles of specific miRNA-mRNA pairs in vivo. Nat. Protoc. 6, 2035-2049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton A. A., Knaut H., Giraldez A. J. (2011). miRNA regulation of Sdf1 chemokine signaling provides genetic robustness to germ cell migration. Nat. Genet. 43, 204-211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton C. A., Kumar I., Reed M. W., Brown N. J. (2007). Neuropilins in physiological and pathological angiogenesis. J. Pathol. 212, 237-248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez Y., Fernández-Hernando C., Pober J. S., Sessa W. C. (2007). Dicer dependent microRNAs regulate gene expression and functions in human endothelial cells. Circ. Res. 100, 1164-1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Vázquez J., Gitler A. D., Fraser S. D., Berk J. D., Pham V. N., Fishman M. C., Childs S., Epstein J. A., Weinstein B. M. (2004). Semaphorin-plexin signaling guides patterning of the developing vasculature. Dev. Cell 7, 117-123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner N., Grose R. (2010). Fibroblast growth factor signalling: from development to cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 116-129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vumbaca F., Phoenix K. N., Rodriguez-Pinto D., Han D. K., Claffey K. P. (2008). Double-stranded RNA-binding protein regulates vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA stability, translation, and breast cancer angiogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 772-783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Aurora A. B., Johnson B. A., Qi X., McAnally J., Hill J. A., Richardson J. A., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N. (2008). The endothelial-specific microRNA miR-126 governs vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Dev. Cell 15, 261-271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. (2000). The Zebrafish Book. A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Press; [Google Scholar]

- Wienholds E., Kloosterman W. P., Miska E., Alvarez-Saavedra E., Berezikov E., de Bruijn E., Horvitz H. R., Kauppinen S., Plasterk R. H. (2005). MicroRNA expression in zebrafish embryonic development. Science 309, 310-311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff C., Roy S., Ingham P. W. (2003). Multiple muscle cell identities induced by distinct levels and timing of hedgehog activity in the zebrafish embryo. Curr. Biol. 13, 1169-1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Liu M., Wang C., Lin C., Sun Y., Jin D. (2011). Down-regulation of MiR-206 promotes proliferation and invasion of laryngeal cancer by regulating VEGF expression. Anticancer Res. 31, 3859-3863 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt T., Gay C. M., Blondelle J., Singh M. K., Flaherty K. M., Means P. C., Herwig L., Krudewig A., Belting H. G., Affolter M., et al. (2011). Semaphorin-PlexinD1 signaling limits angiogenic potential via the VEGF decoy receptor sFlt1. Dev. Cell 21, 301-314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]