Abstract

The last decade has witnessed an explosion in the identification of genes, mutations in which appear sufficient to cause clinical phenotypes in humans. This is especially true for disorders of ciliary dysfunction in which an excess of 50 causal loci are now known; this discovery was driven in part by an improved understanding of the protein composition of the cilium and the co-occurrence of clinical phenotypes associated with ciliary dysfunction. Despite this progress, the fundamental challenge of predicting phenotype and or clinical progression based on single locus information remains unsolved. Here, we explore how the combinatorial knowledge of allele quality and quantity, an improved understanding of the biological composition of the primary cilium, and the expanded appreciation of the subcellular roles of this organelle can be synthesized to generate improved models that can explain both causality but also variable penetrance and expressivity.

Introduction

Since the recognition of ciliary dysfunction in Kartagener syndrome in 1976 [1], the cilium has been transformed from a largely ignored, sometimes considered vestigial organelle, to a subcellular structure that contributes significantly to the health care burden. This has been especially true for disorders of primary cilia, immotile organelles that are now understood to be near ubiquitous in the vertebrate body plan (for detailed reviews of primary and motile cilia see [2,3]). Subsequent to the identification of mutations in the intraflagellar transport (IFT) protein Ift88 in the orpk mouse model of renal cystic disease [4], mutations in ciliary genes have been attributed to human genetic disorders at an accelerating rate.

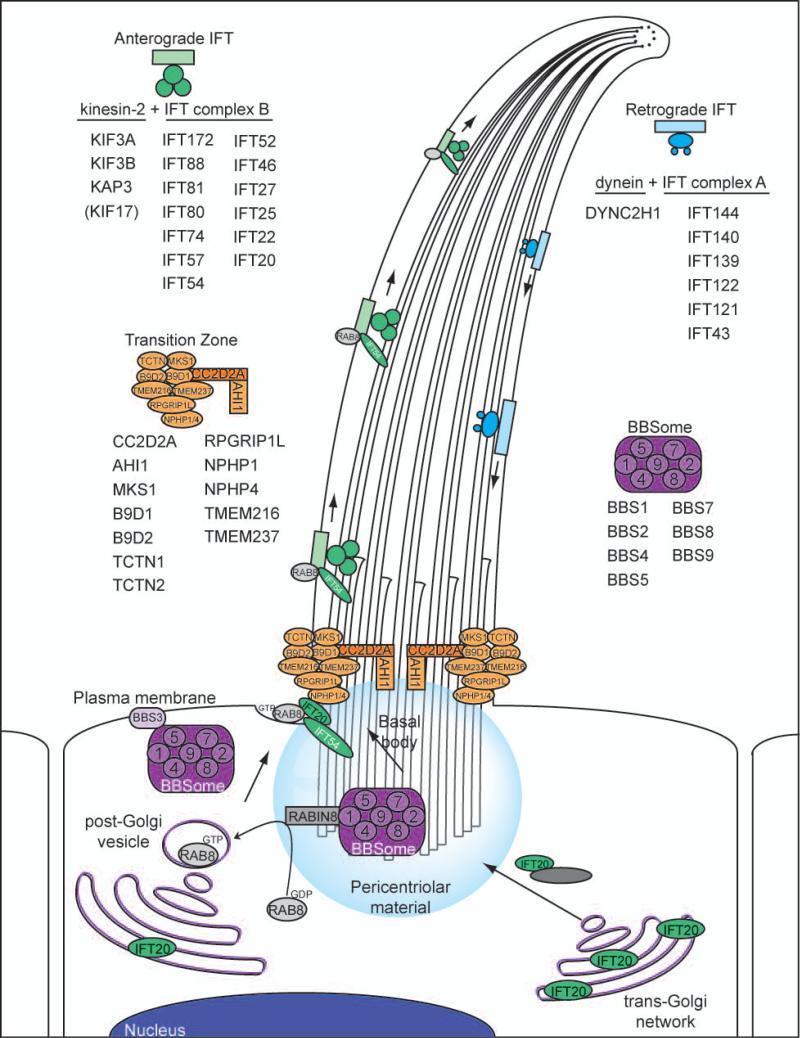

Tethered to the cell at the basal body and supported by a microtubule-based scaffold, cilia emanate from the apical portion of nearly all vertebrate cell types (Figure 1; for a recent review, see [2,3]). Combined proteomic, comparative genomics, and transcription analysis data in both vertebrate and invertebrate ciliated organisms and cell types have yielded a predicted protein repertoire of ~1000 proteins required for the generation and maintenance of cilia (ref [5] and www.ciliaproteome.org). The intersect of these data with candidate gene lists generated from traditional and next-generation sequencing approaches have contributed to the identification of novel ciliopathy genes and clinical entities (Tables 1, 2).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of functional ciliary complexes and their components. Four biochemically characterized ciliary complexes have emerged as facilitators of discrete functions in the cilium. First, the BBSome (purple) consists of seven proteins, mutations in which have been implicated in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. The BBSome has been proposed to interact with BBS3/ARL6 at the plasma membrane and sort membrane proteins to the cilium [43,120]. Second, the transition zone complex (orange) has emerged as a regulator of ciliogenesis and ciliary membrane assembly and is comprised of proteins encoded by MKS and JBTS genes [36,39,121,122]. Third, once loaded into the primary cilium, anterograde protein transport is conducted with IFT complex B proteins and heterotrimeric kinesin motors (green) [44]. Finally, retrograde recycling of proteins from the tip of the cilium back to the cell body is governed by IFT complex A proteins and dynein motors (blue) [44], all of which have been implicated in the skeletal dysplasia ciliopathies including Sensenbrenner syndrome, JATD, and SRP.

Table 1.

Phenotypic overlap and genes contributing to total mutational load in ten ciliopathies

| ▶ INCREASING PHENOTYPIC SEVERITY ▶ | REFERENCE | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP MR | KD RP, MR, CH, HD | KD, RP SI, HD | RP, KD, MR, CH P, SI, O, HD | RP, KD, MR, P, O, CH, SI, HD | KD, P, HD, EN SI | P, CF, KD, CNS | P, CF, KD | P, TD, KD, CF | TD, LS, P, RP, KD, HD | Primary locus | Modifying locus | |

| Gene | LCA | NPHP | SLS | JBTS | BBS | MKS | OFD | CED | SRP | JATD | ◯ | ○ |

| AIPL1 | ◯ | [66] | ||||||||||

| CRB1 | ◯ | [67,68] | ||||||||||

| CRX | ◯ | [69] | ||||||||||

| GUCY2D | ◯ | [70,71] | ||||||||||

| IMPDH1 | ◯ | [71] | ||||||||||

| RDH12 | ◯ | [72] | ||||||||||

| RPE65 | ◯ | [73] | ||||||||||

| RPGRIP1 | ◯ | [74] | ||||||||||

| LCA5 | ◯ | [75] | ||||||||||

| CEP290 | ◯ | ◯ ○ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | [11,16,26-28] | [31] | ||||

| NPHP1 | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | [54,76,77] | ||||||||

| INVS | ◯ | ◯ | [6,78] | |||||||||

| NPHP3 | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | [13,14] | ||||||||

| NPHP4 | ◯ | ◯ | [79,80] | |||||||||

| NPHP5 | ◯ | ◯ | [81] | |||||||||

| GLIS2 | ◯ | [82] | ||||||||||

| NEK8 | ◯ | [83] | ||||||||||

| ATXN10 | ◯ | [84] | ||||||||||

| AHI1 | ○ | ◯ | [85,86] | [32] | ||||||||

| TMEM67 | ◯ | ◯ | ○ | ◯ | [16,87-89] | [16] | ||||||

| RPGRIP1L | ○ | ◯ | ○ | ◯ | ○ | ◯ | [19-21] | [35] | ||||

| ARL13B | ◯ | [90] | ||||||||||

| OFD1 | ◯ | ◯ | [91,92] | |||||||||

| INPP5E | ◯ | [93] | ||||||||||

| TMEM216 | ◯ | ○ | ◯ | [22,23] | [23] | |||||||

| TMEM138 | ◯ | [47] | ||||||||||

| TMEM237 | ◯ | ○ | [39] | |||||||||

| TCTN1 | ◯ | [36] | ||||||||||

| TCTN2 | ◯ | ◯ | [84,94] | |||||||||

| KIF7 | ◯ | ○ | ○ | ○ | [56] | [40] | ||||||

| CEP41 | ◯ | ○ | [95] | [95] | ||||||||

| BBS1 | ◯ ○ | [96] | [97,98] | |||||||||

| BBS2 | ◯ ○ | ◯ | [99,100] | [29,97] | ||||||||

| BBS3 | ◯ | [101,102] | ||||||||||

| BBS4 | ◯ | ◯ ○ | ◯ | [99,103,104] | [48] | |||||||

| BBS5 | ◯ | [105] | ||||||||||

| BBS6 | ◯ ○ | ◯ | [99,106] | [29,48,97] | ||||||||

| BBS7 | ◯ | [107] | ||||||||||

| BBS8 | ◯ | [7] | ||||||||||

| BBS9 | ◯ | [108] | ||||||||||

| BBS10 | ◯ | ◯ | [48,109] | |||||||||

| BBS11 | ◯ | [110] | ||||||||||

| BBS12 | ◯ | [49] | ||||||||||

| SDCCAG8 | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | [17,18] | ||||||||

| WDPCP | ◯ | ○ | [111] | [111] | ||||||||

| MGC1203 | ○ | [33] | ||||||||||

| MKS1 | ◯ | ◯ ○ | [15,16] | [16] | ||||||||

| CC2D2A | ◯ | ◯ | [112,113] | |||||||||

| B9D1 | ◯ | [114] | ||||||||||

| B9D2 | ◯ | [38] | ||||||||||

| WDR35 | ◯ | ◯ | [115,116] | |||||||||

| IFT43 | ◯ | [51] | ||||||||||

| IFT144 | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | [52] | ||||||||

| DYNC2H1 | ◯ ○ | ◯ | [53,117] | [118] | ||||||||

| NEK1 | ◯ ○ | [118] | [118] | |||||||||

| IFT80 | ◯ | [50] | ||||||||||

| TTC21B | ◯ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◯ | [25] | [25] | |||||

Ciliopathies- LCA: Leber congenital amaurosis, NPHP: Nephronophthisis, SLS: Senior-Loken Syndrome, JBTS: Joubert Syndrome, BBS: Bardet-Biedl Syndrome, MKS: Meckel-Gruber Syndrome, OFD: Orofacialdigital Syndrome, CED: Sensenbrenner Syndrome, SRP: Short rib polydactyly, JATD: Jeune Asphyxiating Thoracic Dystrophy.

Phenotypic features- RP: Retinopathy, KD: Kidney disease, MR: Mental retardation, P: Polydactyly, O: Obesity, CH: Cerebellar hypoplasia, SI: Situs inversus, HD: Hepatic disease, EN: Encephalocele, CF: Craniofacial defect, TD: Thoracic dystrophy, LS: Limb shortening. Bold type indicates primary characteristics

Table 2.

Phenotypic overlap in ten ciliopathies (adapted from refs [8,9]). Prevalence of individual phenotypes (if known) is indicated as dark blue (50-100%; primary clinical diagnostic criteria); and pale blue (0-50%); no shading (no data available).

| Ciliopathy Phenotype | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciliopathy | Retinitis pigmentosa | Renal cystic disease | Situs inversus | Mental retardation/ developmental delay | Hypoplasia of corpus callosum | Dandy-Walker malformation | Posterior encephalocele | Hepatic disease | Polydactyly | Craniofacial abnormality | Bone malformation | |

| Leber Congenital Amaurosis | LCA | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||||

| Nephronophthisis | NPHP | ○ | ||||||||||

| Senior Loken Syndrome | SLS | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||

| Joubert Syndrome | JBTS | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| Bardet Biedl Syndrome [119] | BBS | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| Meckel Gruber Syndrome | MKS | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| Oro-facial-digital Syndrome | OFD | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||||

| Cranioectodermal Dysplasia | CED | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||

| Short Rib Polydactyly | SRP | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||||

| Jeune Asphyxiating Thoracic Dystrophy | JATD | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||||

Initially, mutations in the basal body and axonemal protein INVS/NPHP2 were implicated in the isolated renal cystic disease nephronophthisis (NPHP) either with or without situs inversus (Table 2) [6]. At the same time, a causal association was demonstrated between the basal body protein BBS8 and Bardet-Biedl Syndrome (BBS), a multisystemic disorder involving both developmental abnormalities (polydactyly, mental retardation and developmental delay; Table 2) and degenerative phenotypes (retinal degeneration and renal cystic disease) [7]. Since these discoveries, an excess of 50 causal loci have been identified for >15 clinically discrete disorders (Table 1). In 2006, recognition of the phenotypic overlap of such disorders led to the conceptual unification of the ciliopathies and the progressive prediction that as many as 100 human rare disorders may be driven (at least in part) by structural and or functional defects in the primary cilium [8,9]. At present, although each ciliopathy remains individually rare, collectively their contribution to the overall genetic disease burden in humans approaches population frequency similar to that of common defects such as Down syndrome [10], with a minimal estimated collective incidence of ~1:1,000 conceptuses (>100 ciliopathies × average incidence of 1:100,000).

The progress in gene discovery allows us to begin to address one of the next great challenges in human and medical genetics, namely our ability to glean information of prospective value from patient genomes in terms of information, management, and treatment options. Success in this endeavor will be aided by the hyper-acceleration of whole genome sequencing of patients and healthy individuals. At the same time, a paradigm shift is also required, where apparently Mendelian mutations will have to be considered, at minimum, in the background of the entire genome. As we discuss below, the primary cilium and its constellation of human pathologies represents an ideal system to build context-dependent genetic models and to test their capacity to inform and predict the natural course of the phenotype.

Here, we highlight our current understanding of primary locus contribution to disease, ranging from overt to subtle correlations between allelism and phenotype. We also review the accumulating evidence for second-site modification of primary ciliopathy loci and explore the concept of mutational burden within the ciliary protein repertoire as a major modulator of phenotypic determinism. Taken together, these observations begin to outline a model in which a systems-based approach can a) inform the causality of ciliopathy phenotypes; and b) offer a potential paradigm for the study of other disorders that exhibit genetic heterogeneity and clinical variability.

Genetic causality and single locus genotype-phenotype correlations

The ciliopathies are characterized by extensive intra- and inter-familial phenotypic variability. As shown in Table 1, mutations in genes necessary for the elaboration or function of the primary cilium can give rise to dramatically different phenotypes that, crucially, have markedly different clinical outcomes and management requirements (see Table 2 for a summary of hallmark clinical ciliopathy phenotypes). Further, mutations in the same gene can also give rise to radically different clinical phenotypes (see overlaps in Table 1). Nonetheless, in some instances, tenuous phenotype-genotype correlations at a single locus have been possible, where the nature and/or strength of mutational effect on protein function can correlate with specific clinical entities. In two instances, specific mutations have been shown to drive single-organ pathology: a branch site mutation in intron 26 of CEP290 is sufficient to cause Leber Congenital Amaurosis (LCA), one of the most frequent causes of non-syndromic early childhood blindness [11], while a mutation in a BBS8 exon that is expressed in a retina-specific manner is sufficient to cause retinitis pigmentosa [12].

In other cases, the strength of allele effect on protein function at a single locus can correlate well with phenotypic severity and pleiotropy. For example, null alleles in NPHP3 cause neonatal lethal Meckel-Gruber syndrome (MKS) a pleiotropic disorder hallmarked by a triad of renal cystic disease, central nervous system defects (most commonly occipital encephalocele) and postaxial polydactyly [13]. However, hypomorphic NPHP3 alleles have been implicated in NPHP [14]. Likewise, essentially all MKS fetuses attributed to dysfunction of MKS1 bear null alleles at this locus [15], while hypomorphic MKS1 mutations have been shown to cause BBS [16].

Some reports have also hinted at intermediate phenotype-genotype correlations: although classical associations are not obvious, it has been possible to observe an apparent enrichment for the presence/absence of specific endophenotypes. For instance, mutations in SDCCAG8 can cause both BBS and NPHP, with no clear enrichment for specific types of alleles or mutated positions in the protein [17]. However, all BBS individuals with causal SDCCAG8 mutations reported to date exhibit no polydactyly and have a high frequency of end-stage renal disease [18]. The simplest explanation for these data is that SDCCAG8 mutations establish a range of pathology that straddles unique, perhaps tissue-specific components of the two principal disorders (NPHP and BBS).

At the same time, mutational analyses of clinically diverse patients for some ciliopathy loci have hinted at complex genetic architecture in which affected organ systems, but not severity, can be explained by allelism at a single locus. In several instances, the phenotypic spectrum can be restricted to clinical entities with extensive phenotypic overlap, such as in the case of mutations in RPGRIP1L that can cause either MKS or Joubert Syndrome (JBTS), a disorder characterized typically by hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis, neuroradiologic “molar tooth sign,” and accompanying features including retinal dystrophy, polydactyly, and renal abnormalities (Table 1, 2). However, the severity of disease is highly variable ranging from moderate (JBTS) to severe (MKS) when the primary genetic lesion is functional null in both instances [19-21]. Similarly, mutations in TMEM216, give rise to a similar oscillation of phenotypes within and across patient families with JBTS and MKS [22,23].

Even so, the ciliopathy disease spectrum offers accumulating examples in which the type and position of mutations at a causal locus offer little guidance to predict the development of phenotypes. Homozygous null mutations in Ttc21b are embryonic lethal in the alien mouse mutant [24] and have never been found in humans. However, heterozygous null mutations in trans with a hypomorphic allele at this locus have been reported in patients with NPHP (with extra-renal manifestations) or Jeune Asphyxiating Thoracic Dystrophy (JATD), a chondrodysplasia characterized by a constricted thoracic cage, short limbs, polydactyly, and often hepatorenal abnormalities [25]. Mutations in CEP290 manifest even more extreme clinical variability; in addition to LCA, null alleles at this locus have been shown to cause each of NPHP, JBTS, MKS, and BBS, four clinically distinct entities with markedly different phenotypic characteristics and clinical outcomes [11,16,26-28] (Table 1, 2).

Oligogenic inheritance in ciliopathies

In addition to profound clinical variability, the ciliopathies are characterized by complex relationships between disease genes and alleles that remain partially understood. Despite multiple indirect lines of evidence in favor of epistatic phenomena, such as the frequent lack of correlation between allelism at a single locus with disease severity or particular endophenotypes as described above for TTC21B or CEP290, the community is still faced with a paucity of direct evidence to enable prediction of phenotype based uniquely on genotype. Still, there are some notable exceptions in which we have been successful toward dissecting disease modulation.

The earliest direct example of complex inheritance in this group of disorders was the identification of rare asymptomatic individuals with homozygous truncating mutations in BBS genes [29]. At the time of discovery, a digenic (or digenic triallelic) model was proposed by virtue of the fact that affected individuals within non-penetrant families also had heterozygous pathogenic mutations at other BBS loci. Such genetic interactions have since been reported for a significant number of causal ciliary genes and have also been recapitulated in experiments utilizing either genetic crosses or transient multi-gene suppression in model organisms.

Since the initial report of oligogenic phenomena in BBS, which we now know to account for ~25% of BBS families [30], there have been noteworthy instances in which it is possible to explain disease manifestation through two paradigms: the interaction of either two known primary causative loci; or the interaction of one known primary ciliopathy locus with a modulator that is necessary but not sufficient to give rise to disease. One example of the former instance emerged when individuals with JBTS were screened for mutations in three known causative genes: NPHP1, CEP290, and AHI1. This analysis revealed that individuals harboring NPHP1 mutations had an enriched incidence of pathogenic CEP290 or AHI1 lesions in trans, which likely explained extra-renal symptoms [31]. Recent functional studies in murine models substantiated these genetic predictions; there is a retinal-specific exacerbation in double transgenic Nphp1-/- Ahi1-/+ mice in comparison to mice with only Nphp1 ablation [32].

Biochemical interaction studies have assisted with the identification of two additional modifiers of ciliary disease. First, MGC1203/CCDC28B was shown to interact directly with BBS4, co-localize to the centrosome, and resulted in a synergistic increase of early gastrulation defects in mid-somitic zebrafish embryos when both orthologs were co-suppressed in vivo. In addition to an enrichment of the mutant allele in patients, the MGC1203/CCDC28B 430T variant was shown to segregate with a penetrant phenotype in a BBS1 family [33]. Second, as part of an unbiased resequencing effort to better understand mutational load at the RPGRIP1L locus, a hypomorphic Ala229Thr change of modest allele frequency in the general population (2.8%) was found to be enriched significantly in ciliopathy patients with retinal phenotypes. Moreover, this change diminishes interaction between RPGRIP1L and RPGR, one of the most frequently mutated loci in X-linked retinitis pigmentosa [34], providing initial mechanistic insight for the effects of this modulator of retinal endophenotypes [35]. Taken together, these examples highlight the importance of multifaceted genetic, animal model, and biochemical approaches to enable the dissection of modulators in rare disease.

Although such digenic models are attractive to explain observed variable penetrance (rare) and variability (common) they remain limited in two important ways. First, the activity of alleles at a single locus or in pairwise relationships still occurs in the context of the genetic background of the genome and epigenome. Second, any attempt to apply absolute language that can describe accurately such relationships is an oversimplification of biological reality. The conflict arises in part for the clinical need to ascribe a discrete entity for the benefit of physicians and patients that are at odds with the biological reality of continua of cellular processes and their malfunction.

Admittedly, our understanding of the genetic interactions of ciliopathy loci still remains poor and can be attributable, at least in part, to the difficulty in identifying second-site modifiers. Coincident with causal discoveries, some alleles have been reported across the ciliopathy spectrum, which are clearly enriched in patients but not sufficient to cause disease under a Mendelian paradigm. Still, we anticipate that this class of molecular lesion is underrepresented in the literature for two reasons. First, this likely represents the classical bias of the human genetics community in which patients for whom causal mutations at a single locus have been discovered are not screened further. Second, patients with bona fide pathogenic heterozygous mutations at a single locus are less likely to be reported because of the challenge in interpreting those genotypes in the clinical setting. These are problems that should be overcome as we transition from genocentric sequencing paradigms to whole genome studies. However, this technological leap will not solve, but rather accentuate both our interpretive challenges and the limitations of classical dichotomization of genetic mutations in rare diseases as causal or non-causal.

Further dissection of total mutational load

Although the lack of genotype-phenotype correlations is not unique to this group of disorders, the ciliopathies do represent a potentially unique opportunity to understand such vexing genetic problems such as variable penetrance and expressivity. This is primarily due to four reasons. First, the combinatorial dataset derived from evolutionary genetic studies, transcriptional studies, and mass spectrometry analysis of cilia and basal body across phyla has led to a reasonably populated catalog of the proteins required to build, maintain and operate the primary cilium [5]. Second, by virtue of its architecture, the primary cilium represents a semi-closed system that can now be studied in its (near) entirety, since it is proposed to be strictly regulated by a transition zone complex consisting of MKS and JBTS proteins that regulate ciliogenesis and membrane assembly [36]. Third, significant progress in understanding the subcellular functions of the primary cilium [37] have enabled the scientific enterprise to connect genetics with cell biology and biochemistry, thus enabling us to monitor and assess the functional output of this organelle in cells and in whole organisms. Finally, in large part because of these advances, it is now possible to evaluate the functional consequences of variation found in any given ciliary gene/protein in a physiologically relevant context through the use of genetic mutants [3], in vivo complementation assays [16,25,35,38-42], and a constellation of in vitro morphometric, protein localization and signaling reporter assays [25,41].

Unbiased medical resequencing studies are beginning to provide an initial glimpse at how mutational burden might be contributing across the ciliopathy disease spectrum, representing a paradigm shift away from examination of distinct clinical entities, or the deployment of narrow genetic approaches that require prior assumptions on the mode of inheritance, such as linkage analysis or homozygosity mapping. Mutational analysis of TTC21B was the first large-scale analysis of an axonemal protein-encoding locus across the ciliopathy spectrum ranging from mild (isolated NPHP), moderate (BBS, JBTS) to severe (MKS, JATD), and sequencing data combined with functional assays revealed a five-fold enrichment of pathogenic TTC21B variants in the ciliopathy cohort in comparison to healthy controls [25]. Moreover, genetic interaction studies demonstrated that genetic sensitization of retrograde IFT likely exacerbates at least 13 different primary ciliopathy loci. Taken together, TTC21B mutations contribute to the mutational burden in 5% of individuals with ciliopathies. Even so, analysis of one single locus was insufficient to understand phenotypic severity across clinical subgroups. Expanded studies involving multi-gene/protein macromolecular complexes such as the BBSome [43], transition zone complexes [36,39], the IFT complex [44], or the entire ciliary proteome [5] are required to achieve enhanced resolution of the combinatorial effect of molecular lesions that drive particular phenotypes (Figure 1).

The observed complex genetic interactions seen in some ciliopathy loci (highlighted as primary and/or modifying loci in Table 1), although challenging to understand and prone to interpretive bias, have nonetheless given rise to a number of predictions that have been supported by experimental evidence. First, oligogenic interactions have provided a parsimonious means to explain intra-familiar variability. Second, deep sequencing of ciliopathy loci, such as RPGRIP1L or TTC21B, have unearthed a combined enrichment of rare alleles significantly above population average [25,35]. Third, the prediction that some families should manifest clinically discrete ciliopathies has also been shown to be true. Not only are there examples of numerous families with co-segregated MKS and JBTS [45], but some families have also recently been reported with more distantly related phenotypes such as Joubert and Bardet-Biedl Syndrome [46]. Finally, genetic interaction studies in model organisms have supported the notion of trans modification; pairwise suppression of orthologous genes in zebrafish embryos has shown epistatic interaction of a multitude of NPHP, BBS and MKS loci [16,23,25,33,39,47-49].

The concept of phenotypic oscillation and its limits

Query of the London dysmorphology database, and the more recent mining of Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database led to the estimate that at least one hundred discrete disorders were likely ciliopathies, prioritized based on the co-occurrence of multiple core features that include retinitis pigmentosa, renal cystic disease, polydactyly, mental retardation, situs inversus, agenesis of the corpus callosum, Dandy-Walker malformation, encephalocele, and hepatic disease [8,9] (Table 2). This information has had intrinsic discovery value because it accelerated the identification of previously unknown ciliopathies and causal ciliopathy genes as exemplified by the uncovering of mutations of IFT80 as the first causal JATD locus [50]. Just as importantly, however, are the biological lessons on the cellular levels that are emerging from clinical and genetic observations.

Although the current availability of genome wide sequencing data in ciliopathies is limited, we can begin to appreciate some substructure that is of likely biological relevance. For example, causal mutations in components of the IFT complex are heavily enriched in three disorders, JATD, SRP, and Sensenbrenner syndrome (Figure 1), a disorder characterized by craniofacial abnormalities and hepatorenal defects (CED; also known as Cranioectodermal dysplasia; Table 2); the common clinical presentation of these three ciliopathies is defects in bone formation [25,50-53]. Likewise, mutations in genes that are sufficient to cause various forms of isolated or highly penetrant cystic renal disease, such as NPHP1 [54], have emerged as proteins that encode components of the transition zone (Figure 1). Finally, mutations in the genes that cause BBS are almost always associated with fully penetrant retinal degeneration [9]. Each of these observations might suggest a topological modularity, wherein particular organ systems are most susceptible to defects of specific functional protein complexes. Consequently, the oscillation of accessory phenotypes in addition to the highly penetrant disease phenotype (photoreceptor loss for BBS proteins; renal cystic disease in transition zone mutations; chondrodysplasias for IFT mutations) might be due, at least in part, to the sensitization of other tissues by a combination of stochastic factors and trans mutations affecting alternate complexes elsewhere in the cilium.

It is likely that this working model is a vast oversimplification; not all families with mutations in the retrograde IFT protein-encoding gene TTC21B have skeletal defects [25]. Also, the ciliary protein complexes that drive additional hallmark phenotypes, such as central nervous system defects, still remain poorly resolved, or may not drive such phenotypes under the direction of specific ciliary macromolecular complexes. Even so, this does represent a framework in which the spatiotemporal involvement of primary causal mutations establishes at least some primary ciliopathy phenotypes that oscillate around a median defined by biological boundaries and whose amplitude is influenced by second site modifiers.

Guilty by association

Amidst the rapid progress in establishing new ciliopathy clinical entities and/or novel contributing loci it is important to ensure that in each case, dysfunction of the primary cilium can be causally attributed to disease. As discussed earlier, cilia play critical roles in a broad range of paracrine signal transduction pathways. Therefore it is not difficult to imagine how perturbation of some of these pathways might also phenocopy ciliopathies. For example, mutations in KIF7, the human ortholog of Drosophila Costal-2 and an agonist of Shh pathway that interacts with Shh effector protein Smoothened (Smo) cause hydrolethalus (HLS) and acrocallosal (ACLS) syndromes [40]. Further, Kif7 has been shown to traffic within the ciliary axoneme upon Shh stimulation in vitro [55]. The subsequent report of KIF7 mutations in JBTS [56] does support the notion that HLS and ACLS also both belong under the ciliopathy umbrella. However, the marked phenotypic differences between the three disorders may or may not be driven by ciliary related differences in the genomes of these patients or by the function of this protein in a hitherto unknown context.

The NPHP-like locus XPNPEP3, encoding an aminopeptidase, further illustrates the conundrum of understanding the cellular basis of a seemingly ciliopathy phenotype. From a clinical perspective, the renal phenotype of patients with recessive mutations in XPNPEP3 is a hallmark ciliopathy feature broadly indistinguishable from patients with mutations in bona fide ciliary genes. However, initial biochemical and immunocytochemical studies suggest that this protein might not have direct ciliary roles [57]. It is an open question therefore, whether this mitochondrial X-prolyl aminopeptidase protein regulates ciliary function through the processing of ciliary proteins with a proline at the third N-terminal position of the peptide, or whether its cystogenic role is driven by an altogether different mechanism.

Some necessary next steps

Our ability to discern the effect of alleles on humans, both in cis and trans contexts will necessitate the improvement of four key areas. Broadly, these areas will delineate a blueprint of the protein networks within the primary cilium that will allow us to evaluate how specific dysfunction of components, as well as the combinatorial effect of variation across the biological system, can drive specific pathology. It is necessary to compile a higher fidelity list of the proteins required for ciliary biogenesis and function and to accurately map the roles of these proteins in discrete spatiotemporal contexts. This ambitious endeavor could be conceptualized in the following aspects.

First, it will be necessary to understand the composition of the cilium in a cell type and developmental or regenerative stage specific manner, since emerging evidence suggests that not all primary cilia are alike. For instance, loss of members of the tectonic protein family can lead to defective ciliogenesis in certain cell types; Tctn1-/- mice lack cilia in the node and neural tube, but do generate cilia in the notochord and early gut epithelium [36]. Immunohistochemical analysis of Tctn1-/- has correlated this diverse phenotype with changes in ciliary protein content. Ift20 is differentially localized in the neural tube and perineural mesenchymal cells in a Tctn1-/- context, however Ift88, another anterograde IFT protein, is similarly present in both cell types regardless of the presence of TCTN1 [36].

Second, the above observation transitions into a certain critical point, namely the notion that ciliary proteins can have non ciliary functions in specific tissues and cell types. For example, IFT20 localizes to the Golgi complex in ciliated mammalian cells [58]. Moreover, IFT components including IFT20, IFT57, and IFT88 have be found to play critical roles at the immune synapse in non-ciliated human lymphoid and myeloid cells [59]. Some ciliary proteins localize to the nucleus in certain contexts; RPGR has been localized to the nucleus of photoreceptor cells where it can interact with members of the chromodomain family [60], while several BBS proteins have been shown to have nuclear export signals and to similarly localize to the nucleus to interact with ring finger transcriptional repressors [61]. A major unknown is whether these aspects are related to or independent from ciliary function, and by extension, whether these ciliary-independent roles drive specific pathology seen in some ciliopathies.

Third, in addition to content and cellular context the functional connectivity of ciliary proteins is an area bereft of knowledge. Despite having recognized the presence of two macromolecular complexes required for the anterograde (complex B) and retrograde (complex A) transport of cargo along the ciliary axoneme [44] (Figure 1), the precise stoichiometry (context-dependent variance thereof) of the ~20 proteins that compose the IFT complexes A and B is not yet solved. Likewise, many but not all of the BBS proteins have been shown to assemble into a stable particle, termed the BBSome, in cultured cells [43]. However, we do not know whether this is true in vivo and if so, in what cell types. The interaction of several MKS and JBTS proteins has also been shown to regulate ciliogenesis and ciliary membrane assembly [36]. The aggregation of some BBS proteins in subcellular compartments in neurons hints at additional diversity whose biological relevance is unknown [62]. It is not difficult to imagine that as ciliary and ciliopathy proteins are identified, the complexity and the wiring of this system will increase exponentially.

Finally, the primary cilium has emerged as a major driver for the propagation or fine-tuning of a broad range of signaling pathways that are triggered either by small molecules or by paracrine signals [3]. Emerging evidence suggests that different tissues, cell types, developmental, and homeostatic time points have variable tolerance for defects in some but not all of these pathways and it is critical that we understand which pathways might underpin which phenotypes common across all ciliopathies. For example, mounting evidence suggests that PCP (β-catenin independent Wnt signaling), as demonstrated in Fat4 mutants, plays a major role in the manifestation of renal cystic pathology seen in most but not all ciliopathies [63,64]. At the same time, injury repair in the same tissue can trigger significant canonical Wnt signaling phenotypes in ciliopathy mouse mutants, as shown recently in the Ahi1-/- murine models [65].

Ultimately, a perhaps idealized endpoint of the ciliopathy field will be the generation of a context-specific protein network onto which both improved phenotype information and genetic variation discovered in patients can be overlaid. We anticipate that the spatial relationship of both Mendelian and non-Mendelian pathogenic alleles in such a construct will help derive predictions of clinical utility and enhance dramatically the predictive power of the genotype.

Acknowledgments

The field of ciliopathies has expanded logarithmically during the past few years and it is not possible to cover all discoveries in a singe article; we apologize to our colleagues whose work might have been overlooked or covered in extreme brevity. We are grateful to Christelle Golzio and Edwin Oh for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01EY021872 from the National Eye Institute (E.E.D.), R01HD04260 from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (N.K.), R01DK072301 and R01DK075972 from the National Institute of Diabetes Digestive and Kidney Disorders (N.K.), and the European Union (EU-SYSCILIA; E.E.D., N.K.) NK is a Distinguished George W. Brumley Professor.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Afzelius BA. A human syndrome caused by immotile cilia. Science. 1976;193:317–319. doi: 10.1126/science.1084576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fliegauf M, Benzing T, Omran H. When cilia go bad: cilia defects and ciliopathies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:880–893. doi: 10.1038/nrm2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerdes JM, Davis EE, Katsanis N. The vertebrate primary cilium in development, homeostasis, and disease. Cell. 2009;137:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pazour GJ, Dickert BL, Vucica Y, Seeley ES, Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB, Cole DG. Chlamydomonas IFT88 and its mouse homologue, polycystic kidney disease gene tg737, are required for assembly of cilia and flagella. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:709–718. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.3.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gherman A, Davis EE, Katsanis N. The ciliary proteome database: an integrated community resource for the genetic and functional dissection of cilia. Nat Genet. 2006;38:961–962. doi: 10.1038/ng0906-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otto EA, Schermer B, Obara T, O'Toole JF, Hiller KS, Mueller AM, Ruf RG, Hoefele J, Beekmann F, Landau D, et al. Mutations in INVS encoding inversin cause nephronophthisis type 2, linking renal cystic disease to the function of primary cilia and left-right axis determination. Nat Genet. 2003;34:413–420. doi: 10.1038/ng1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ansley SJ, Badano JL, Blacque OE, Hill J, Hoskins BE, Leitch CC, Kim JC, Ross AJ, Eichers ER, Teslovich TM, et al. Basal body dysfunction is a likely cause of pleiotropic Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nature. 2003;425:628–633. doi: 10.1038/nature02030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badano JL, Mitsuma N, Beales PL, Katsanis N. The ciliopathies: an emerging class of human genetic disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:125–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker K, Beales PL. Making sense of cilia in disease: the human ciliopathies. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2009;151C:281–295. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hook EB. Down syndrome rates and relaxed selection at older maternal ages. Am J Hum Genet. 1983;35:1307–1313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.den Hollander AI, Koenekoop RK, Yzer S, Lopez I, Arends ML, Voesenek KE, Zonneveld MN, Strom TM, Meitinger T, Brunner HG, et al. Mutations in the CEP290 (NPHP6) gene are a frequent cause of Leber congenital amaurosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:556–561. doi: 10.1086/507318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12*.Riazuddin SA, Iqbal M, Wang Y, Masuda T, Chen Y, Bowne S, Sullivan LS, Waseem NH, Bhattacharya S, Daiger SP, et al. A splice-site mutation in a retina-specific exon of BBS8 causes nonsyndromic retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.001. [This paper highlights a rare example in which ciliopathy gene mutations can drive single organ pathology. In this instance, a splice-site mutation in a retina specific exon of BBS8 causes retinitis pigmentosa.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergmann C, Fliegauf M, Bruchle NO, Frank V, Olbrich H, Kirschner J, Schermer B, Schmedding I, Kispert A, Kranzlin B, et al. Loss of nephrocystin-3 function can cause embryonic lethality, Meckel-Gruber-like syndrome, situs inversus, and renal-hepatic-pancreatic dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:959–970. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olbrich H, Fliegauf M, Hoefele J, Kispert A, Otto E, Volz A, Wolf MT, Sasmaz G, Trauer U, Reinhardt R, et al. Mutations in a novel gene, NPHP3, cause adolescent nephronophthisis, tapeto-retinal degeneration and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2003;34:455–459. doi: 10.1038/ng1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kyttala M, Tallila J, Salonen R, Kopra O, Kohlschmidt N, Paavola-Sakki P, Peltonen L, Kestila M. MKS1, encoding a component of the flagellar apparatus basal body proteome, is mutated in Meckel syndrome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:155–157. doi: 10.1038/ng1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leitch CC, Zaghloul NA, Davis EE, Stoetzel C, Diaz-Font A, Rix S, Alfadhel M, Lewis RA, Eyaid W, Banin E, et al. Hypomorphic mutations in syndromic encephalocele genes are associated with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nat Genet. 2008;40:443–448. doi: 10.1038/ng.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17*.Otto EA, Hurd TW, Airik R, Chaki M, Zhou W, Stoetzel C, Patil SB, Levy S, Ghosh AK, Murga-Zamalloa CA, et al. Candidate exome capture identifies mutation of SDCCAG8 as the cause of a retinal-renal ciliopathy. Nat Genet. 2010;42:840–850. doi: 10.1038/ng.662. [This work represents one of the first whole-exome approaches to the discovery of ciliopathy loci and also highlights the difficulties in phenotype-genotype correlations, since qualitatelively similar mutations in SDCCAG8 can cause both NPHP and BBS.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaefer E, Zaloszyc A, Lauer J, Durand M, Stutzmann F, Perdomo-Trujillo Y, Redin C, Bennouna Greene V, Toutain A, Perrin L, et al. Mutations in SDCCAG8/NPHP10 Cause Bardet-Biedl Syndrome and Are Associated with Penetrant Renal Disease and Absent Polydactyly. Mol Syndromol. 2011;1:273–281. doi: 10.1159/000331268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arts HH, Doherty D, van Beersum SE, Parisi MA, Letteboer SJ, Gorden NT, Peters TA, Marker T, Voesenek K, Kartono A, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the basal body protein RPGRIP1L, a nephrocystin-4 interactor, cause Joubert syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:882–888. doi: 10.1038/ng2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delous M, Baala L, Salomon R, Laclef C, Vierkotten J, Tory K, Golzio C, Lacoste T, Besse L, Ozilou C, et al. The ciliary gene RPGRIP1L is mutated in cerebello-oculo-renal syndrome (Joubert syndrome type B) and Meckel syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:875–881. doi: 10.1038/ng2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf MT, Saunier S, O'Toole JF, Wanner N, Groshong T, Attanasio M, Salomon R, Stallmach T, Sayer JA, Waldherr R, et al. Mutational analysis of the RPGRIP1L gene in patients with Joubert syndrome and nephronophthisis. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1520–1526. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edvardson S, Shaag A, Zenvirt S, Erlich Y, Hannon GJ, Shanske AL, Gomori JM, Ekstein J, Elpeleg O. Joubert syndrome 2 (JBTS2) in Ashkenazi Jews is associated with a TMEM216 mutation. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valente EM, Logan CV, Mougou-Zerelli S, Lee JH, Silhavy JL, Brancati F, Iannicelli M, Travaglini L, Romani S, Illi B, et al. Mutations in TMEM216 perturb ciliogenesis and cause Joubert, Meckel and related syndromes. Nat Genet. 2010;42:619–625. doi: 10.1038/ng.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tran PV, Haycraft CJ, Besschetnova TY, Turbe-Doan A, Stottmann RW, Herron BJ, Chesebro AL, Qiu H, Scherz PJ, Shah JV, et al. THM1 negatively modulates mouse sonic hedgehog signal transduction and affects retrograde intraflagellar transport in cilia. Nat Genet. 2008;40:403–410. doi: 10.1038/ng.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25**.Davis EE, Zhang Q, Liu Q, Diplas BH, Davey LM, Hartley J, Stoetzel C, Szymanska K, Ramaswami G, Logan CV, et al. TTC21B contributes both causal and modifying alleles across the ciliopathy spectrum. Nat Genet. 2011;43:189–196. doi: 10.1038/ng.756. [Unbiased medical resequencing in ciliopathy cohorts combined with in vivo and in vitro functional annotation highlighted the concept of mutational load in a ciliopathy locus. This work also highlighted how functional annotation was required to unmask a significant enrichment of pathogenic mutations in patients.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baala L, Audollent S, Martinovic J, Ozilou C, Babron MC, Sivanandamoorthy S, Saunier S, Salomon R, Gonzales M, Rattenberry E, et al. Pleiotropic effects of CEP290 (NPHP6) mutations extend to Meckel syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:170–179. doi: 10.1086/519494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sayer JA, Otto EA, O'Toole JF, Nurnberg G, Kennedy MA, Becker C, Hennies HC, Helou J, Attanasio M, Fausett BV, et al. The centrosomal protein nephrocystin-6 is mutated in Joubert syndrome and activates transcription factor ATF4. Nat Genet. 2006;38:674–681. doi: 10.1038/ng1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valente EM, Silhavy JL, Brancati F, Barrano G, Krishnaswami SR, Castori M, Lancaster MA, Boltshauser E, Boccone L, Al-Gazali L, et al. Mutations in CEP290, which encodes a centrosomal protein, cause pleiotropic forms of Joubert syndrome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:623–625. doi: 10.1038/ng1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katsanis N, Ansley SJ, Badano JL, Eichers ER, Lewis RA, Hoskins BE, Scambler PJ, Davidson WS, Beales PL, Lupski JR. Triallelic inheritance in Bardet-Biedl syndrome, a Mendelian recessive disorder. Science. 2001;293:2256–2259. doi: 10.1126/science.1063525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deveault C, Billingsley G, Duncan JL, Bin J, Theal R, Vincent A, Fieggen KJ, Gerth C, Noordeh N, Traboulsi EI, et al. BBS genotype-phenotype assessment of a multiethnic patient cohort calls for a revision of the disease definition. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:610–619. doi: 10.1002/humu.21480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tory K, Lacoste T, Burglen L, Moriniere V, Boddaert N, Macher MA, Llanas B, Nivet H, Bensman A, Niaudet P, et al. High NPHP1 and NPHP6 mutation rate in patients with Joubert syndrome and nephronophthisis: potential epistatic effect of NPHP6 and AHI1 mutations in patients with NPHP1 mutations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1566–1575. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32**.Louie CM, Caridi G, Lopes VS, Brancati F, Kispert A, Lancaster MA, Schlossman AM, Otto EA, Leitges M, Grone HJ, et al. AHI1 is required for photoreceptor outer segment development and is a modifier for retinal degeneration in nephronophthisis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:175–180. doi: 10.1038/ng.519. [This paper represents one of few examples to date that demonstrate modulation of a specific endophenotype by two ciliopathy loci in trans by virtue of in vivo evidence of an exacerbated retinal phenotype in Nphp1-/- Ahi1-/+ mice.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Badano JL, Leitch CC, Ansley SJ, May-Simera H, Lawson S, Lewis RA, Beales PL, Dietz HC, Fisher S, Katsanis N. Dissection of epistasis in oligogenic Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nature. 2006;439:326–330. doi: 10.1038/nature04370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shu X, Black GC, Rice JM, Hart-Holden N, Jones A, O'Grady A, Ramsden S, Wright AF. RPGR mutation analysis and disease: an update. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:322–328. doi: 10.1002/humu.20461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khanna H, Davis EE, Murga-Zamalloa CA, Estrada-Cuzcano A, Lopez I, den Hollander AI, Zonneveld MN, Othman MI, Waseem N, Chakarova CF, et al. A common allele in RPGRIP1L is a modifier of retinal degeneration in ciliopathies. Nat Genet. 2009;41:739–745. doi: 10.1038/ng.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36*.Garcia-Gonzalo FR, Corbit KC, Sirerol-Piquer MS, Ramaswami G, Otto EA, Noriega TR, Seol AD, Robinson JF, Bennett CL, Josifova DJ, et al. A transition zone complex regulates mammalian ciliogenesis and ciliary membrane composition. Nat Genet. 2011;43:776–784. doi: 10.1038/ng.891. [This work describing Tctn1-/- mice exemplifies emerging tissue-specific differences in primary ciliary function.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lancaster MA, Schroth J, Gleeson JG. Subcellular spatial regulation of canonical Wnt signalling at the primary cilium. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:700–707. doi: 10.1038/ncb2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dowdle WE, Robinson JF, Kneist A, Sirerol-Piquer MS, Frints SG, Corbit KC, Zaghloul NA, van Lijnschoten G, Mulders L, Verver DE, et al. Disruption of a ciliary B9 protein complex causes Meckel syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:94–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang L, Szymanska K, Jensen VL, Janecke AR, Innes AM, Davis EE, Frosk P, Li C, Willer JR, Chodirker BN, et al. TMEM237 is mutated in individuals with a Joubert syndrome related disorder and expands the role of the TMEM family at the ciliary transition zone. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:713–730. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Putoux A, Thomas S, Coene KL, Davis EE, Alanay Y, Ogur G, Uz E, Buzas D, Gomes C, Patrier S, et al. KIF7 mutations cause fetal hydrolethalus and acrocallosal syndromes. Nat Genet. 2011;43:601–606. doi: 10.1038/ng.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41**.Zaghloul NA, Liu Y, Gerdes JM, Gascue C, Oh EC, Leitch CC, Bromberg Y, Binkley J, Leibel RL, Sidow A, et al. Functional analyses of variants reveal a significant role for dominant negative and common alleles in oligogenic Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10602–10607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000219107. [This paper represents the largest functional study of ciliopathy missense changes to date, provides a functional basis to explain oligogenic inheritance in Bardet-Biedl Syndrome, and demonstrates the high level of specificity and sensitivity in in vivo complementation assays to test allele pathogenicity.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42*.Masyukova SV, Winkelbauer ME, Williams CL, Pieczynski JN, Yoder BK. Assessing the pathogenic potential of human Nephronophthisis disease-associated NPHP-4 missense mutations in C. elegans. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2942–2954. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr198. [Functional analysis of worm mutants provided an alternative means of testing the functionality of alleles in ciliopathy genes in vivo.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nachury MV, Loktev AV, Zhang Q, Westlake CJ, Peranen J, Merdes A, Slusarski DC, Scheller RH, Bazan JF, Sheffield VC, et al. A core complex of BBS proteins cooperates with the GTPase Rab8 to promote ciliary membrane biogenesis. Cell. 2007;129:1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedersen LB, Rosenbaum JL. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) role in ciliary assembly, resorption and signalling. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;85:23–61. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00802-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boycott KM, Parboosingh JS, Scott JN, McLeod DR, Greenberg CR, Fujiwara TM, Mah JK, Midgley J, Wade A, Bernier FP, et al. Meckel syndrome in the Hutterite population is actually a Joubert-related cerebello-oculo-renal syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:1715–1725. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46*.Zaki MS, Sattar S, Massoudi RA, Gleeson JG. Co-occurrence of distinct ciliopathy diseases in single families suggests genetic modifiers. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:3042–3049. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34173. [This report of ciliopathy families with distinct phenotypic discordance contributes to the accumulating evidence for intrafamilial modulators of variable penetrance and expressivity.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47*.Lee JH, Silhavy JL, Lee JE, Al-Gazali L, Thomas S, Davis EE, Bielas SL, Hill KJ, Iannicelli M, Brancati F, et al. Evolutionarily Assembled cis-Regulatory Module at a Human Ciliopathy Locus. Science. 2012 doi: 10.1126/science.1213506. [Demonstration of genetic complexity at a Joubert locus that also highlighted the presence of co-evolved functional modules.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stoetzel C, Laurier V, Davis EE, Muller J, Rix S, Badano JL, Leitch CC, Salem N, Chouery E, Corbani S, et al. BBS10 encodes a vertebrate-specific chaperonin-like protein and is a major BBS locus. Nat Genet. 2006;38:521–524. doi: 10.1038/ng1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stoetzel C, Muller J, Laurier V, Davis EE, Zaghloul NA, Vicaire S, Jacquelin C, Plewniak F, Leitch CC, Sarda P, et al. Identification of a novel BBS gene (BBS12) highlights the major role of a vertebrate-specific branch of chaperonin-related proteins in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:1–11. doi: 10.1086/510256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beales PL, Bland E, Tobin JL, Bacchelli C, Tuysuz B, Hill J, Rix S, Pearson CG, Kai M, Hartley J, et al. IFT80, which encodes a conserved intraflagellar transport protein, is mutated in Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy. Nat Genet. 2007;39:727–729. doi: 10.1038/ng2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arts HH, Bongers EM, Mans DA, van Beersum SE, Oud MM, Bolat E, Spruijt L, Cornelissen EA, Schuurs-Hoeijmakers JH, de Leeuw N, et al. C14ORF179 encoding IFT43 is mutated in Sensenbrenner syndrome. J Med Genet. 2011;48:390–395. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2011.088864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bredrup C, Saunier S, Oud MM, Fiskerstrand T, Hoischen A, Brackman D, Leh SM, Midtbo M, Filhol E, Bole-Feysot C, et al. Ciliopathies with skeletal anomalies and renal insufficiency due to mutations in the IFT-A gene WDR19. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:634–643. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dagoneau N, Goulet M, Genevieve D, Sznajer Y, Martinovic J, Smithson S, Huber C, Baujat G, Flori E, Tecco L, et al. DYNC2H1 mutations cause asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy and short rib-polydactyly syndrome, type III. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:706–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hildebrandt F, Otto E, Rensing C, Nothwang HG, Vollmer M, Adolphs J, Hanusch H, Brandis M. A novel gene encoding an SH3 domain protein is mutated in nephronophthisis type 1. Nat Genet. 1997;17:149–153. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liem KF, Jr., He M, Ocbina PJ, Anderson KV. Mouse Kif7/Costal2 is a cilia-associated protein that regulates Sonic hedgehog signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13377–13382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906944106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dafinger C, Liebau MC, Elsayed SM, Hellenbroich Y, Boltshauser E, Korenke GC, Fabretti F, Janecke AR, Ebermann I, Nurnberg G, et al. Mutations in KIF7 link Joubert syndrome with Sonic Hedgehog signaling and microtubule dynamics. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2662–2667. doi: 10.1172/JCI43639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57*.O'Toole JF, Liu Y, Davis EE, Westlake CJ, Attanasio M, Otto EA, Seelow D, Nurnberg G, Becker C, Nuutinen M, et al. Individuals with mutations in XPNPEP3, which encodes a mitochondrial protein, develop a nephronophthisis-like nephropathy. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:791–802. doi: 10.1172/JCI40076. [This work highlights an example of a ciliopathy phenocopy, caused by dysfunction of a non-ciliary protein, XPNPEP3. Although this work suggests that XPNPEP3 processes certain ciliary proteins, it remains unclear whether this mitochondrial protein also has a hitherto unknown ciliary function.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Follit JA, Tuft RA, Fogarty KE, Pazour GJ. The intraflagellar transport protein IFT20 is associated with the Golgi complex and is required for cilia assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:3781–3792. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-02-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Finetti F, Paccani SR, Riparbelli MG, Giacomello E, Perinetti G, Pazour GJ, Rosenbaum JL, Baldari CT. Intraflagellar transport is required for polarized recycling of the TCR/CD3 complex to the immune synapse. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1332–1339. doi: 10.1038/ncb1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shu X, Fry AM, Tulloch B, Manson FD, Crabb JW, Khanna H, Faragher AJ, Lennon A, He S, Trojan P, et al. RPGR ORF15 isoform co-localizes with RPGRIP1 at centrioles and basal bodies and interacts with nucleophosmin. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1183–1197. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gascue C, Tan PL, Cardenas-Rodriguez M, Libisch G, Fernandez-Calero T, Liu YP, Astrada S, Robello C, Naya H, Katsanis N, et al. Direct role of Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins in transcriptional regulation. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:362–375. doi: 10.1242/jcs.089375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tadenev AL, Kulaga HM, May-Simera HL, Kelley MW, Katsanis N, Reed RR. Loss of Bardet-Biedl syndrome protein-8 (BBS8) perturbs olfactory function, protein localization, and axon targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10320–10325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016531108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fischer E, Legue E, Doyen A, Nato F, Nicolas JF, Torres V, Yaniv M, Pontoglio M. Defective planar cell polarity in polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2006;38:21–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saburi S, Hester I, Fischer E, Pontoglio M, Eremina V, Gessler M, Quaggin SE, Harrison R, Mount R, McNeill H. Loss of Fat4 disrupts PCP signaling and oriented cell division and leads to cystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1010–1015. doi: 10.1038/ng.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lancaster MA, Louie CM, Silhavy JL, Sintasath L, Decambre M, Nigam SK, Willert K, Gleeson JG. Impaired Wnt-beta-catenin signaling disrupts adult renal homeostasis and leads to cystic kidney ciliopathy. Nat Med. 2009;15:1046–1054. doi: 10.1038/nm.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sohocki MM, Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, Blackshaw S, Cepko CL, Payne AM, Bhattacharya SS, Khaliq S, Qasim Mehdi S, Birch DG, et al. Mutations in a new photoreceptor-pineal gene on 17p cause Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet. 2000;24:79–83. doi: 10.1038/71732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.den Hollander AI, Heckenlively JR, van den Born LI, de Kok YJ, van der Velde-Visser SD, Kellner U, Jurklies B, van Schooneveld MJ, Blankenagel A, Rohrschneider K, et al. Leber congenital amaurosis and retinitis pigmentosa with Coats-like exudative vasculopathy are associated with mutations in the crumbs homologue 1 (CRB1) gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:198–203. doi: 10.1086/321263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lotery AJ, Jacobson SG, Fishman GA, Weleber RG, Fulton AB, Namperumalsamy P, Heon E, Levin AV, Grover S, Rosenow JR, et al. Mutations in the CRB1 gene cause Leber congenital amaurosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:415–420. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Freund CL, Wang QL, Chen S, Muskat BL, Wiles CD, Sheffield VC, Jacobson SG, McInnes RR, Zack DJ, Stone EM. De novo mutations in the CRX homeobox gene associated with Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet. 1998;18:311–312. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Perrault I, Rozet JM, Calvas P, Gerber S, Camuzat A, Dollfus H, Chatelin S, Souied E, Ghazi I, Leowski C, et al. Retinal-specific guanylate cyclase gene mutations in Leber's congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet. 1996;14:461–464. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, Mortimer SE, Hedstrom L, Zhu J, Spellicy CJ, Gire AI, Hughbanks-Wheaton D, Birch DG, Lewis RA, et al. Spectrum and frequency of mutations in IMPDH1 associated with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa and leber congenital amaurosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:34–42. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Perrault I, Hanein S, Gerber S, Barbet F, Ducroq D, Dollfus H, Hamel C, Dufier JL, Munnich A, Kaplan J, et al. Retinal dehydrogenase 12 (RDH12) mutations in leber congenital amaurosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:639–646. doi: 10.1086/424889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marlhens F, Bareil C, Griffoin JM, Zrenner E, Amalric P, Eliaou C, Liu SY, Harris E, Redmond TM, Arnaud B, et al. Mutations in RPE65 cause Leber's congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet. 1997;17:139–141. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dryja TP, Adams SM, Grimsby JL, McGee TL, Hong DH, Li T, Andreasson S, Berson EL. Null RPGRIP1 alleles in patients with Leber congenital amaurosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1295–1298. doi: 10.1086/320113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.den Hollander AI, Koenekoop RK, Mohamed MD, Arts HH, Boldt K, Towns KV, Sedmak T, Beer M, Nagel-Wolfrum K, McKibbin M, et al. Mutations in LCA5, encoding the ciliary protein lebercilin, cause Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:889–895. doi: 10.1038/ng2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hildebrandt F, Zhou W. Nephronophthisis-associated ciliopathies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1855–1871. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Parisi MA, Bennett CL, Eckert ML, Dobyns WB, Gleeson JG, Shaw DW, McDonald R, Eddy A, Chance PF, Glass IA. The NPHP1 gene deletion associated with juvenile nephronophthisis is present in a subset of individuals with Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:82–91. doi: 10.1086/421846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.O'Toole JF, Otto EA, Frishberg Y, Hildebrandt F. Retinitis pigmentosa and renal failure in a patient with mutations in INVS. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1989–1991. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mollet G, Salomon R, Gribouval O, Silbermann F, Bacq D, Landthaler G, Milford D, Nayir A, Rizzoni G, Antignac C, et al. The gene mutated in juvenile nephronophthisis type 4 encodes a novel protein that interacts with nephrocystin. Nat Genet. 2002;32:300–305. doi: 10.1038/ng996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Otto E, Hoefele J, Ruf R, Mueller AM, Hiller KS, Wolf MT, Schuermann MJ, Becker A, Birkenhager R, Sudbrak R, et al. A gene mutated in nephronophthisis and retinitis pigmentosa encodes a novel protein, nephroretinin, conserved in evolution. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:1161–1167. doi: 10.1086/344395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Otto EA, Loeys B, Khanna H, Hellemans J, Sudbrak R, Fan S, Muerb U, O'Toole JF, Helou J, Attanasio M, et al. Nephrocystin-5, a ciliary IQ domain protein, is mutated in Senior-Loken syndrome and interacts with RPGR and calmodulin. Nat Genet. 2005;37:282–288. doi: 10.1038/ng1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Attanasio M, Uhlenhaut NH, Sousa VH, O'Toole JF, Otto E, Anlag K, Klugmann C, Treier AC, Helou J, Sayer JA, et al. Loss of GLIS2 causes nephronophthisis in humans and mice by increased apoptosis and fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1018–1024. doi: 10.1038/ng2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Otto EA, Trapp ML, Schultheiss UT, Helou J, Quarmby LM, Hildebrandt F. NEK8 mutations affect ciliary and centrosomal localization and may cause nephronophthisis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:587–592. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84*.Sang L, Miller JJ, Corbit KC, Giles RH, Brauer MJ, Otto EA, Baye LM, Wen X, Scales SJ, Kwong M, et al. Mapping the NPHP-JBTS-MKS protein network reveals ciliopathy disease genes and pathways. Cell. 2011;145:513–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.019. [This study highlights the power of a proteomics approach toward uncovering protein interactors in the NPHP/JBTS/MKS complex of proteins in the cilium.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dixon-Salazar T, Silhavy JL, Marsh SE, Louie CM, Scott LC, Gururaj A, Al-Gazali L, Al-Tawari AA, Kayserili H, Sztriha L, et al. Mutations in the AHI1 gene, encoding jouberin, cause Joubert syndrome with cortical polymicrogyria. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:979–987. doi: 10.1086/425985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ferland RJ, Eyaid W, Collura RV, Tully LD, Hill RS, Al-Nouri D, Al-Rumayyan A, Topcu M, Gascon G, Bodell A, et al. Abnormal cerebellar development and axonal decussation due to mutations in AHI1 in Joubert syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1008–1013. doi: 10.1038/ng1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Baala L, Romano S, Khaddour R, Saunier S, Smith UM, Audollent S, Ozilou C, Faivre L, Laurent N, Foliguet B, et al. The Meckel-Gruber syndrome gene, MKS3, is mutated in Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:186–194. doi: 10.1086/510499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Otto EA, Tory K, Attanasio M, Zhou W, Chaki M, Paruchuri Y, Wise EL, Wolf MT, Utsch B, Becker C, et al. Hypomorphic mutations in meckelin (MKS3/TMEM67) cause nephronophthisis with liver fibrosis (NPHP11). J Med Genet. 2009;46:663–670. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.066613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Smith UM, Consugar M, Tee LJ, McKee BM, Maina EN, Whelan S, Morgan NV, Goranson E, Gissen P, Lilliquist S, et al. The transmembrane protein meckelin (MKS3) is mutated in Meckel-Gruber syndrome and the wpk rat. Nat Genet. 2006;38:191–196. doi: 10.1038/ng1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cantagrel V, Silhavy JL, Bielas SL, Swistun D, Marsh SE, Bertrand JY, Audollent S, Attie-Bitach T, Holden KR, Dobyns WB, et al. Mutations in the cilia gene ARL13B lead to the classical form of Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Coene KL, Roepman R, Doherty D, Afroze B, Kroes HY, Letteboer SJ, Ngu LH, Budny B, van Wijk E, Gorden NT, et al. OFD1 is mutated in X-linked Joubert syndrome and interacts with LCA5-encoded lebercilin. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:465–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ferrante MI, Giorgio G, Feather SA, Bulfone A, Wright V, Ghiani M, Selicorni A, Gammaro L, Scolari F, Woolf AS, et al. Identification of the gene for oral-facial-digital type I syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:569–576. doi: 10.1086/318802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bielas SL, Silhavy JL, Brancati F, Kisseleva MV, Al-Gazali L, Sztriha L, Bayoumi RA, Zaki MS, Abdel-Aleem A, Rosti RO, et al. Mutations in INPP5E, encoding inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase E, link phosphatidyl inositol signaling to the ciliopathies. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/ng.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shaheen R, Faqeih E, Seidahmed MZ, Sunker A, Alali FE, AlQahtani K, Alkuraya FS. A TCTN2 mutation defines a novel Meckel Gruber syndrome locus. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:573–578. doi: 10.1002/humu.21507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lee JE, Silhavy JL, Zaki MS, Schroth J, Bielas SL, Marsh SE, Olvera J, Brancati F, Iannicelli M, Ikegami K, et al. CEP41 is mutated in Joubert syndrome and is required for tubulin glutamylation at the cilium. Nat Genet. 2012;44:193–199. doi: 10.1038/ng.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mykytyn K, Nishimura DY, Searby CC, Shastri M, Yen HJ, Beck JS, Braun T, Streb LM, Cornier AS, Cox GF, et al. Identification of the gene (BBS1) most commonly involved in Bardet-Biedl syndrome, a complex human obesity syndrome. Nat Genet. 2002;31:435–438. doi: 10.1038/ng935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Badano JL, Kim JC, Hoskins BE, Lewis RA, Ansley SJ, Cutler DJ, Castellan C, Beales PL, Leroux MR, Katsanis N. Heterozygous mutations in BBS1, BBS2 and BBS6 have a potential epistatic effect on Bardet-Biedl patients with two mutations at a second BBS locus. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1651–1659. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Beales PL, Badano JL, Ross AJ, Ansley SJ, Hoskins BE, Kirsten B, Mein CA, Froguel P, Scambler PJ, Lewis RA, et al. Genetic interaction of BBS1 mutations with alleles at other BBS loci can result in non-Mendelian Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1187–1199. doi: 10.1086/375178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Karmous-Benailly H, Martinovic J, Gubler MC, Sirot Y, Clech L, Ozilou C, Auge J, Brahimi N, Etchevers H, Detrait E, et al. Antenatal presentation of Bardet-Biedl syndrome may mimic Meckel syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:493–504. doi: 10.1086/428679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nishimura DY, Searby CC, Carmi R, Elbedour K, Van Maldergem L, Fulton AB, Lam BL, Powell BR, Swiderski RE, Bugge KE, et al. Positional cloning of a novel gene on chromosome 16q causing Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS2). Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:865–874. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.8.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chiang AP, Nishimura D, Searby C, Elbedour K, Carmi R, Ferguson AL, Secrist J, Braun T, Casavant T, Stone EM, et al. Comparative genomic analysis identifies an ADP-ribosylation factor-like gene as the cause of Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS3). Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:475–484. doi: 10.1086/423903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fan Y, Esmail MA, Ansley SJ, Blacque OE, Boroevich K, Ross AJ, Moore SJ, Badano JL, May-Simera H, Compton DS, et al. Mutations in a member of the Ras superfamily of small GTP-binding proteins causes Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:989–993. doi: 10.1038/ng1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mykytyn K, Braun T, Carmi R, Haider NB, Searby CC, Shastri M, Beck G, Wright AF, Iannaccone A, Elbedour K, et al. Identification of the gene that, when mutated, causes the human obesity syndrome BBS4. Nat Genet. 2001;28:188–191. doi: 10.1038/88925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang H, Chen X, Dudinsky L, Patenia C, Chen Y, Li Y, Wei Y, Abboud EB, Al-Rajhi AA, Lewis RA, et al. Exome capture sequencing identifies a novel mutation in BBS4. Mol Vis. 2011;17:3529–3540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li JB, Gerdes JM, Haycraft CJ, Fan Y, Teslovich TM, May-Simera H, Li H, Blacque OE, Li L, Leitch CC, et al. Comparative genomics identifies a flagellar and basal body proteome that includes the BBS5 human disease gene. Cell. 2004;117:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Katsanis N, Beales PL, Woods MO, Lewis RA, Green JS, Parfrey PS, Ansley SJ, Davidson WS, Lupski JR. Mutations in MKKS cause obesity, retinal dystrophy and renal malformations associated with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nat Genet. 2000;26:67–70. doi: 10.1038/79201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Badano JL, Ansley SJ, Leitch CC, Lewis RA, Lupski JR, Katsanis N. Identification of a novel Bardet-Biedl syndrome protein, BBS7, that shares structural features with BBS1 and BBS2. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:650–658. doi: 10.1086/368204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nishimura DY, Swiderski RE, Searby CC, Berg EM, Ferguson AL, Hennekam R, Merin S, Weleber RG, Biesecker LG, Stone EM, et al. Comparative genomics and gene expression analysis identifies BBS9, a new Bardet-Biedl syndrome gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:1021–1033. doi: 10.1086/498323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Putoux A, Mougou-Zerelli S, Thomas S, Elkhartoufi N, Audollent S, Le Merrer M, Lachmeijer A, Sigaudy S, Buenerd A, Fernandez C, et al. BBS10 mutations are common in ‘Meckel’-type cystic kidneys. J Med Genet. 2010;47:848–852. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.079392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chiang AP, Beck JS, Yen HJ, Tayeh MK, Scheetz TE, Swiderski RE, Nishimura DY, Braun TA, Kim KY, Huang J, et al. Homozygosity mapping with SNP arrays identifies TRIM32, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, as a Bardet-Biedl syndrome gene (BBS11). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6287–6292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600158103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kim SK, Shindo A, Park TJ, Oh EC, Ghosh S, Gray RS, Lewis RA, Johnson CA, Attie-Bittach T, Katsanis N, et al. Planar cell polarity acts through septins to control collective cell movement and ciliogenesis. Science. 2010;329:1337–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1191184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gorden NT, Arts HH, Parisi MA, Coene KL, Letteboer SJ, van Beersum SE, Mans DA, Hikida A, Eckert M, Knutzen D, et al. CC2D2A is mutated in Joubert syndrome and interacts with the ciliopathy-associated basal body protein CEP290. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:559–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tallila J, Jakkula E, Peltonen L, Salonen R, Kestila M. Identification of CC2D2A as a Meckel syndrome gene adds an important piece to the ciliopathy puzzle. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:1361–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hopp K, Heyer CM, Hommerding CJ, Henke SA, Sundsbak JL, Patel S, Patel P, Consugar MB, Czarnecki PG, Gliem TJ, et al. B9D1 is revealed as a novel Meckel syndrome (MKS) gene by targeted exon-enriched next-generation sequencing and deletion analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2524–2534. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gilissen C, Arts HH, Hoischen A, Spruijt L, Mans DA, Arts P, van Lier B, Steehouwer M, van Reeuwijk J, Kant SG, et al. Exome sequencing identifies WDR35 variants involved in Sensenbrenner syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mill P, Lockhart PJ, Fitzpatrick E, Mountford HS, Hall EA, Reijns MA, Keighren M, Bahlo M, Bromhead CJ, Budd P, et al. Human and mouse mutations in WDR35 cause short-rib polydactyly syndromes due to abnormal ciliogenesis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Merrill AE, Merriman B, Farrington-Rock C, Camacho N, Sebald ET, Funari VA, Schibler MJ, Firestein MH, Cohn ZA, Priore MA, et al. Ciliary abnormalities due to defects in the retrograde transport protein DYNC2H1 in short-rib polydactyly syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:542–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Thiel C, Kessler K, Giessl A, Dimmler A, Shalev SA, von der Haar S, Zenker M, Zahnleiter D, Stoss H, Beinder E, et al. NEK1 mutations cause short-rib polydactyly syndrome type majewski. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Beales PL, Elcioglu N, Woolf AS, Parker D, Flinter FA. New criteria for improved diagnosis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome: results of a population survey. J Med Genet. 1999;36:437–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jin H, White SR, Shida T, Schulz S, Aguiar M, Gygi SP, Bazan JF, Nachury MV. The conserved Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins assemble a coat that traffics membrane proteins to cilia. Cell. 2010;141:1208–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121*.Chih B, Liu P, Chinn Y, Chalouni C, Komuves LG, Hass PE, Sandoval W, Peterson AS. A ciliopathy complex at the transition zone protects the cilia as a privileged membrane domain. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:61–72. doi: 10.1038/ncb2410. [This paper contributes to emerging evidence for discrete ciliary complexes and barrier functions at the transition zone.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Williams CL, Li C, Kida K, Inglis PN, Mohan S, Semenec L, Bialas NJ, Stupay RM, Chen N, Blacque OE, et al. MKS and NPHP modules cooperate to establish basal body/transition zone membrane associations and ciliary gate function during ciliogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:1023–1041. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]