Abstract

Introduction/Methods Mutations in POLG1, the gene encoding mitochondrial polymerase gamma (Polγ), have been associated with a number of well-characterized phenotypes. In this study, we report two cases of patients with biallelic POLG1 mutations and stroke. We also performed a review of the literature and report on all clinical studies of patients with POLG1 mutations in which stroke was described in the phenotype. For each patient, genotype and phenotype are reported.

Results Including our two patients, a total of 22 patients have been reported with POLG1 mutations and stroke. The average age of onset of stroke in these patients was 9 years with a range of 1–23 years. In cases where localization was reported, the occipital lobes were the primary location of the infarct. Mutations in the linker–linker or linker–polymerase domains were the most frequent genotype observed. Seizures (16/22) and hepatic dysfunction/failure (8/22) were the most commonly reported symptoms in the stroke cohort.

Conclusion This article raises an underrecognized point that patients with POLG1 mutations may suffer a cerebrovascular accident at a young age. The most common location of the infarction is in the occipital lobe. The presentation may be similar to MELAS and can be misdiagnosed as a migrainous stroke.

Keywords: Mitochondrial, POLG1, Stroke

Introduction

Mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ (Polγ) is the only known human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) polymerase. This enzyme plays an essential role in maintaining mtDNA integrity. Biallelic mutations in POLG1 cause a deficiency of Polγ and lead to a variety of phenotypes. Bernard Alpers began to delineate the history of POLG1-related disorders in 1931, when he published the first case of diffuse progressive gray matter degeneration in children with severe epilepsy and cortical blindness (Alpers 1931). In 1999, Naviaux was the first to report POLG1 dysfunction and mtDNA depletion in a patient with Alpers syndrome (Naviaux et al. 1999). Since its discovery less than a decade ago, more than 150 mutations in POLG1 have been associated with a spectrum of phenotypes including Progressive External Ophthalmoplegia (PEO), Alpers–Huttenlocher Syndrome (psychomotor retardation, intractable epilepsy, liver failure), and Ataxia Neuropathy Spectrum Disorders, among others (Blok et al. 2009; Milone and Massie 2010; Rahman and Hanna 2009; Van Goethem et al. 2001; Wong et al. 2008).

In this report, we describe two patients with Ataxia-Neuropathy (AN) and stroke due to POLG1 mutations and provide a review of the literature.

Cases

Case 1

A 28-year-old woman presented to clinic for evaluation of progressive peripheral neuropathy symptoms of 8 years duration. Her peripheral neuropathy symptoms were primarily sensory and consisted of decreased sensation, paresthesias in her feet, and shooting pains in her legs. She was born full term by vaginal delivery with a birth weight of 7 lb and no perinatal complications. She had no significant childhood illnesses prior to the age of 7, when she was hospitalized for a week long episode of headache, fever, lethargy, and seizures. She was found to have bilateral occipital infarcts also associated with visual field deficits. Infectious workup was negative and cerebral angiography revealed no abnormalities. A diagnosis of MELAS (mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes) was suspected. However, sequencing of the entire mtDNA did not reveal any known or potentially pathogenic mutations known to cause MELAS or other mitochondrial disorder. Subsequent to this episode, bilateral hemianopsia, intractable partial seizures, and migraine headaches persisted. The patient began valproate therapy at age 11 and suffered hepatic encephalopathy which resolved after carnitine therapy. At age 21, she first noted a burning sensation in her feet and gait imbalance which had since progressed. Her family history was negative for others with similar complaints.

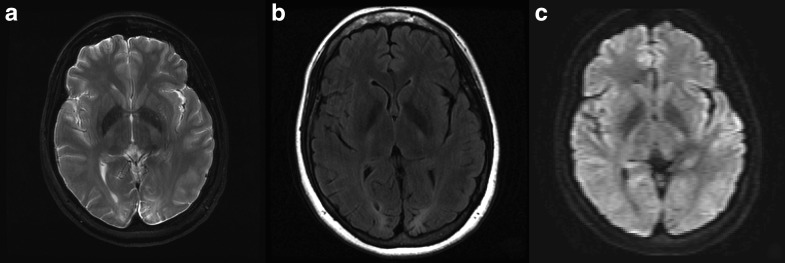

Plasma creatinine, lactate, ALT, and creatine kinase were normal. Spinal fluid analysis revealed an elevated total protein (122 mg/dl nl ≤ 60 mg/dl); there were no oligoclonal bands. Brain MRI demonstrated focal areas of T2 signal abnormality and volume loss in the occipital lobes bilaterally, left greater than right, consistent with old infarctions; there was no sign of recent ischemia (Fig. 1). EEG showed a mild degree of nonspecific generalized slowing, maximal over the left occipital head region. EMG of the left lower extremity revealed a length-dependent sensory peripheral neuropathy.

Fig. 1.

(a, b) T2 and flair sequences demonstrate focal areas of T2 signal abnormality and volume loss in the left greater than right occipital lobes, consistent with prior infarcts. (c) Diffusion-weighted imaging is negative for recent ischemia

Gene sequencing of POLG1 identified a c.1399G → A (A467T) mutation on both alleles (e.g., the homozygous state) and confirmed a diagnosis of POLG1-Related Ataxia-Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder.

Case 2

A 39-year-old man presented for evaluation of progressive gait ataxia of 15 years duration; past medical history was also significant for migraine, right occipital infarction with residual left homonymous heminanopsia, seizure disorder, peripheral neuropathy, ophthalmoplegia, and myoclonus. The patient was healthy until age 18 when he suffered an acute right occipital infarction in the setting of an excruciating headache and a secondary generalized seizure. Four-vessel cerebral angiogram and spinal fluid analysis were normal. His initial diagnosis was migraine-related cerebral infarction. He was left with a residual left homonymous hemianopsia. An attempt to treat his seizures with valproate resulted in depressed mood and mild encephalopathy; he discontinued valproate therapy 6 weeks later. In his mid-1920s, he began to develop progressive gait unsteadiness, mild upper-extremity ataxia, and was found to have evidence of peripheral neuropathy. In his mid-1930s, he began to experience mild, but progressive, dysarthria and had occasional episodes of dysphagia. He had no significant family history of similar complaints.

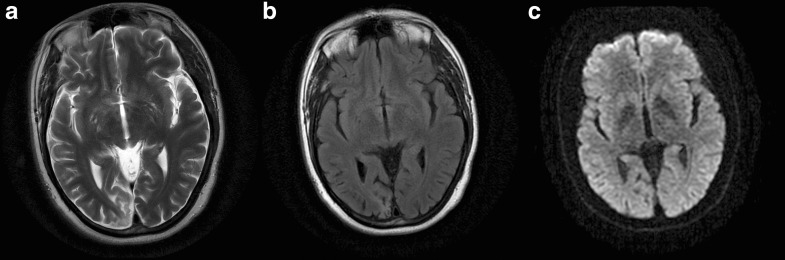

Serum creatinine, lactate, ALT, and creatine kinase were normal. Brain MRI revealed findings consistent with an old infarction in the posteromedial right occipital lobe (Fig. 2). EMG findings were consistent with a mild length-dependent sensorimotor axonal peripheral neuropathy with no evidence for a myopathy. Echocardiography revealed no abnormalities.

Fig. 2.

(a, b) T2 and flair sequences demonstrate encephalomalacia involving the posteromedial right occipital lobe at the site of a prior infarct. (c) No recent sites of cortical infarction on diffusion imaging

POLG1 gene sequencing revealed homozygosity for the c.1399G → A (A467T) mutation and the patient was diagnosed with POLG1-Related Ataxia-Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder. Following his diagnosis, he was placed on a mitochondrial cocktail consisting of alpha-lipoic acid, levocarnitine, and coenzyme Q10 and was advised to take l-arginine in light of his history of stroke. He is currently 40 years of age and his condition remains stable.

Discussion

POLG1 Mutations and Stroke

POLG1 mutations are associated with a broad range of clinical phenotypes including Alpers–Huttenlocher syndrome, PEO, and Ataxia-Neuropathy Spectrum Disorders; however, reports of cases involving stroke are rare (Blok et al. 2009; Milone and Massie 2010; Rahman and Hanna 2009; Stewart et al. 2009; Van Goethem et al. 2001; Wong et al. 2008). Including the above two cases, we found 22 reported cases of POLG1 mutations associated with stroke and stroke-like symptoms in the literature (Table 1) (Blok et al. 2009; Deschauer et al. 2007; Horvath et al. 2006; Kollberg et al. 2006; Wong et al. 2008). Five of these 22 patients were clinically characterized to have Ataxia-Neuropathy Spectrum phenotype, 13 had a phenotype consistent with Alpers, and four patients were unclassified. Given the severity of the phenotypes observed among members of the stroke cohort, phenotypes of moderate to high severity might be more likely to be further complicated by stroke.

Table 1.

Patients with POLG1 mutation and stroke. ANS ataxia neuropathy spectrum, MELAS mitchondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, stroke, U Unknown, PEO progressive external ophthalmoplegia

| Patient | Study | Family history | Sex | Age of onset | Phenotype: symptoms | Lab findings | MRI findings | Allele 1 Domain | Allele 2 Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Current study | None | M | 18 | ANS: occipital stroke, visual field deficit, peripheral neuropathy, migraine, epilepsy, ataxia, myoclonus | Elevated CSF protein | T2 signal abnormality and volume loss in left > right occipital lobes consistent with prior infarcts | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker |

| 2 | Current study | None | F | 7 | ANS: occipital stroke, visual field deficit, peripheral neuropathy, epilepsy, migraine, Valproate-induced hepatic necrosis | No abnormal labs | T2 hyperintensity in the posteromedial right occipital lobe, consistent with prior infarct | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker |

| 3 | Horvath et al., Brain (2006) | None | M | 7 | Alpers: stroke-like episode, seizures | – | – | 1880G → A (R627Q) Linker | 3287G → A (R1096H) Polymerase |

| 4 | Horvath et al., Brain (2006) | None | M | 4 | Alpers: stroke-like episode, myoclonus | – | – | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker | 2740A → C (T914P) Polymerase |

| 5 | Horvath et al., Brain (2006) | Consanguineous | M | 8 | Alpers: stroke-like episode | – | – | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker |

| 6 | Wong et al., Hum Mutat (2008) | None | M | 1 | Alpers: stroke, hypotonia | Elevated serum lactate and liver transaminases | – | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker | 2157 + 5_ + 6GC → AG Linker |

| 7 | Wong et al., Hum Mutat (2008) | None | F | 2 | Alpers: stroke | Elevated serum lactate and liver transaminases | – | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker | 2542G → A (G848S) Polymerase |

| 8 | Wong et al., Hum Mutat (2008) | None | F | 9 | Alpers: stroke, ataxia, exercise intolerance | Elevated liver transaminases | – | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker | 2542G → A (G848S) Polymerase |

| 9 | Wong et al., Hum Mutat (2008) | None | F | 15 | ANS: stroke, chorea, ataxia, ptosis, retinitis pigmentosa, liver transplant | Elevated serum lactate and liver transaminases | – | 2554C → T (R852C) Polymerase | 32G → A (G11D) Exonuclease 1880G → C (R627Q) Linker |

| 10 | Wong et al., Hum Mutat (2008) | None | F | 16 | U: occipital stroke, short stature, Leigh-like disease, neuropathy, dystonia, chorea, diabetes, myoclonus | No reported abnormal labs | – | 1550G → T (G517V) Linker | – |

| 11 | Blok et al., J Med Genet (2009) | None | F | 19 | U: MELAS-like features, occipital epilepsy | – | – | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker | 2740A → C (T914P) Polymerase |

| 12 | Blok et al., J Med Genet (2009) | None | F | 1 | Alpers: epilepsy, deafness, retinitis pigmentosa, hemiparesis, liver failure | – | – | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker | 2772_2773 delG (K925Rfs42X) Polymerase |

| 13 | Blok et al., J Med Genet (2009) | None | F | 1 | Alpers: occipital strokes, growth retardation, focal epilepsy, liver failure, died of heart failure | – | – | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker | 2869G → C (A957P) Polymerase |

| 14 | Deschauer et al., Neurology (2007) | None | M | 23 | ANS: occipital stroke-like episode, headache, seizures, peripheral neuropathy, myopathy | Mild increase in CSF protein, elevated serum lactate | Increased T2 signaling from right occipital cortex sparing deeper white matter | 1880G → A (R627Q) Linker | 2542G → A (G848S) Polymerase |

| 15 | Kollberg et al., J Neuropathol Exp Neurol (2006) | Maternal grandmother: tremor and hepatopathy; Brother: tremor | F | 1 | Alpers: stroke-like episodes, epilepsy, ptosis, external ophthalmoplegia, valproate-induced liver failure, died at 4 years of multiple organ failure | Elevated serum and CSF lactate, elevated liver transaminase | Atrophy of both occipital lobes, high signal intensity in occipital lobe white matter | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker | 1720C → T (R574W) Linker |

| 16 | Kollberg et al., J Neuropathol Exp Neurol (2006) | Sister: POLG1 mutation and Alper Syndrome | M | 11 | ANS: migrainous headaches, ataxia, myoclonus, seizures, L hemiparesis, PEO, peripheral neuropathy | No reported abnormal labs | Increased T2 signaling from right motor cortex | 2243G → C (W748S) 3428A → G Linker | 695G → A (R232H) Exonuclease |

| 17 | Kollberg etal., J Neuropathol Exp Neurol (2006) | None | M | 1 | Alpers: transient L hemiparesis, myoclonus, seizures, died of liver failure at 13 months | Elevated serum lactate, liver transaminases and acylcarnitine fraction. Mitochondrial complex 1 deficiency | – | 3488T → G (M1163R) Polymerase | – |

| 18 | Stewart et al., J Med Genet (2009) | None | N/A | 1 | Alpers: stroke-like episodes | – | – | 32G → A (G11D) 2554C → T (R852C) Polymerase | 2243G → C (W748S) Linker |

| 19 | Montine et al., Clin Neuropathol (1995) | None | M | 17 | Alpers: severe headaches, multiple stroke-like episodes with visual deficits, seizures, hemorrhagic pancreatitis | Elevated serum lipase | Bilateral occipital lobe lesions with increased T2-weighted signal, non-enhancing | a | a |

| 20 | Hopkins et al., J Child Neurol (2010) | Grandmother: ataxia, bilateral basal ganglia infarcts, posterior spinal column degeneration. Identical twin suffered same symptoms | F | 16 | U: diabetes, basal ganglia strokes, choreiform movements, psychosis and epilepsy | Elevated serum lactate. Chronic myopathic changes | Increased T1 and decreased T2 in bilateral basal ganglia and thalami | 1550G →T (G517V) Linker | – |

| 21 | Hopkins et al., J Child Neurol (2010) | Grandmother: ataxia, bilateral basal ganglia infarcts, posterior spinal column degeneration. Identical twin suffered same symptoms | F | 17 | U: diabetes, strokes, psychosis and epilepsy | Elevated serum lactate | Bilateral basal ganglia infarctions | 1550G → T (G517V) Linker | – |

| 22 | Naviaux et al., Ann Neurol (2004) | Brother: alpers | M | 1 | Alpers: encephalopathy, ataxia, thalamic infarct | Elevated serum lactate and liver transaminases | CT: thalamic infarct | 1399G → A (A467T) Linker | 2899G → T (E873X) Polymerase |

aNo detected point mutations in mitochondrial DNA at positions 3243 or 3271 as reported in patients with MELAS

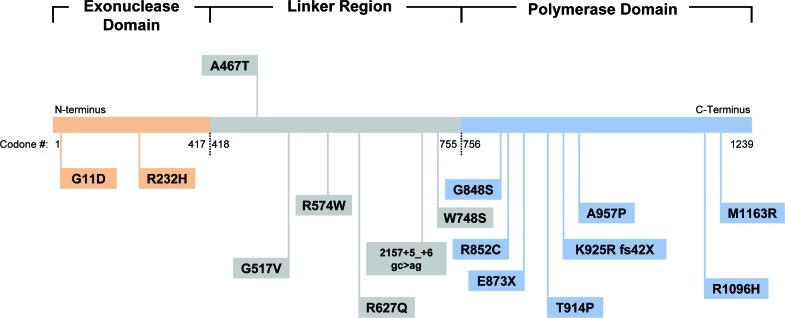

The region of POLG1 between the exonuclease and polymerase has been termed the linker region (Fig. 3). Both of our patients were homozygous for the c.1399G → A (A467T) mutation located in the linker region of the POLG1 gene. Linker mutations are the most common causes of POLG1-related mitochondrial disorders, among which the A467T substitution is the most frequently observed (Chan et al. 2005a; Luoma et al. 2005). In vitro studies of the effects of the A467T mutation suggest that it leads to severely reduced mtDNA polymerase activity (4% of wild type mtDNA polymerase activity) and disrupts binding of the POLG2 accessory subunit (Chan et al. 2005b; Tzoulis et al. 2006). The impaired accessory subunit interaction and reduced polymerase activity is the likely mechanism responsible for mtDNA depletion (Chan et al. 2005b).

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of the POLG1 gene: exonuclease domain (codon 1–417), linker domain (codon 418–755), and polymerase domain (codon 756–1239)

Mutations of POLG1 may also occur in the polymerase domain; these alterations affect mtDNA replication and can lead to reduced mtDNA copy number or to mtDNA deletions. Within the stroke cohort, all but one patient had at least one mutation in the linker region. Five patients were observed to have both mutations in the linker region, 11 patients were compound heterozygotes for mutations in both the linker and polymerase region, and one patient was a compound heterozygote for mutations in both the linker and exonuclease region (Fig. 3). Four patients had only one mutation detected, three of which were in the linker region and one in the polymerase domain of POLG1. These patients are suspected to have a second mutation, which is undetectable by current molecular genetic sequencing techniques.

The average age of onset of stroke or stroke-like symptoms in these patients was 9 years with a range of 1–23 years. Other commonly associated symptoms, in order of decreasing frequency, were: seizures (16/22), hepatic dysfunction/failure (8/22), myoclonus (6/22), peripheral neuropathy (3/22), migraine (3/22), and myopathy (3/22). There was no consistent constellation of symptoms associated with POLG1 mutations and stroke among these patients.

Of the cases where the localization of the stroke was noted, 7/13 were located in the occipital region (Blok et al. 2009; Deschauer et al. 2007). MRI findings were available in nine patients. In five of nine patients, increased T2 signal was present in the occipital lobes. These findings were consistent with old infarction. Two patients had increased T2 signal in the basal ganglia, one in the basal ganglia and right frontal lobe and the other in the right frontal lobe without abnormalities in the occipital lobes. Laboratory findings were available in 15 patients. The most common laboratory abnormalities included elevated serum lactate (9/15) and elevated liver transaminases (7/15).

Similarity to Stroke in MELAS

The first patient discussed (Case 1) was initially thought to have MELAS because of the presence of cerebral infarction. MELAS is a well-characterized syndrome associated with stroke-like episodes due to mutations in mtDNA. Stroke-like episodes in MELAS are often accompanied by a severe migraine-like headache and/or seizures. Many patients also suffer from lactic acidosis or encephalopathy. Cerebral infarctions in MELAS are generally localized in the parietooccipital regions and are not in any particular vascular distribution (Rahman and Hanna 2009).

Patients with MELAS have been found to have impaired endothelial function and vasoconstriction when compared to controls. Therefore, one of the theories for the etiology of stroke in MELAS is impaired vasodilation and a deficiency of nitric oxide (NO) (Koga et al. 2007). Some have studied the benefits of administering l-arginine, a precursor to the vasodilator NO in patients with MELAS stroke-like episodes (Koga et al. 2002, 2005, 2007). It has been found that intravenously administered l-arginine improved acute stroke-like symptoms in MELAS patients (Koga et al. 2005). Furthermore, long-term supplementation of oral l-arginine has been shown to improve endothelial dysfunction and potentially play a role in the prevention of stroke-like episodes in MELAS (Koga et al. 2006).

Similar to the MELAS stroke-like episodes, many patients with the POLG1 mutation and stroke have reported migrainous headache, seizures, and cortical blindness in association with the stroke. Given the similarity of the stroke-like episodes in MELAS when compared to those with POLG1 mutations and stroke, it is certainly warranted to investigate the role of endothelial dysfunction in their stroke-like episodes. Currently, no treatment recommendations exist for prevention of stroke in patients with POLG1 mutations.

Similarity to Migrainous Infarction

As mentioned previously, Case 2 was initially diagnosed with a migrainous infarction. Migraine with aura is a well-established risk factor for ischemic stroke (Spector et al. 2010). According to the International Headache Society, migrainous infarction is defined as one or more migrainous aura symptoms associated with an ischemic brain lesion in the appropriate territory as demonstrated by neuroimaging. The diagnostic criteria include: (1) The attack in a patient with migraine with aura is typical of previous attacks, except that one or more aura symptoms persist for >60 min; (2) Neuroimaging demonstrates ischemic infarction in a relevant area; and (3) The infarction is not attributed to another disorder. Patients with migrainous infarction generally have neurological deficits in the vascular territory of the aura and have an associated lesion present on neuroimaging.

A number of potential mechanisms have been proposed for the migrainous stroke. These hypotheses include vasospasm, endothelial dysfunction, activation of the thrombotic cascade, increased platelet activation, and medications (namely triptans and ergotamine) (Del Zotto et al. 2008). Patients who have other stroke risk factors in the setting of migraine are also generally predisposed to an increased risk of stroke. Thus, a number of recommendations are in place to help prevent stroke in patients with migraine including treatment of modifiable risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and hypercholesterolemia), avoiding estrogen containing oral contraceptives and medications with vasoconstrictive action (triptans), and migraine prophylaxis (Del Zotto et al. 2008).

When comparing the characteristics of stroke in patients with POLG1 mutations and those of the migrainous stroke, there exist a number of similarities, but also a number of important differences. The two are similar in that the stroke can occur in the setting of a migraine or migraine-like episode. Patients with stroke and POLG1 mutations have reported aura during their stroke episodes. However, migrainous strokes are generally not associated with seizure activity, lactic acidosis, or other associated symptoms. In addition, migrainous strokes typically occur in the vascular distribution of the aura and occur in patients older than those who possess POLG1 mutations. If a patient presents with a migrainous stroke, it is important to follow this patient long-term to assure the lack of development of symptoms that might warrant further investigations for a mitochondrial cytopathy.

Conclusion

We describe 2 new cases and review a total of 22 cases of patients with stroke in the setting of disease-causing POLG1 mutations. In general, these strokes occur in children under the age of 10, but can present at a later age. In cases where localization is reported, the occipital lobes are the primary location of the infarct. Linker–linker or linker–polymerase domain mutations were most commonly identified in the described patients with stroke in the setting of a more severe phenotype, such as Ataxia-Neuropathy Spectrum or Alpers. Stroke in the setting of POLG1 mutations has a number of similarities to migrainous infarcts, but is most similar to stroke-like episodes in the MELAS syndrome. While neither a mechanism for stroke, nor any effective means of treatment or prophylaxis of stroke in patients with POLG1 mutations has been described, given its similarity to the MELAS stroke, it is possible that these two entities share a similar mechanism. Given the benefit of l-arginine for patients with MELAS, it would be reasonable to study its effect in POLG1-related mitochondrial disorders.

Take-Home Statement

This article raises an important and underrecognized clinical point that stroke can occur in patients with POLG1 mutations.

Mr. Waleed Brinjikji was involved in conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Dr. Jerry Swanson was involved in conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Ms. Carrie Zabel was involved in conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Dr. Peter Dyck was involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Dr. Jennifer Tracy was involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Dr. Ralitza Gavrilova was involved in conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. She is the GUARANTOR for the article.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

No ethics committee approval was necessary.

No funding was needed.

According to Mayo Clinic policy, patients give consent when they complete initial paperwork for their first visit. At that time, they are asked whether they have objections to use of information/images for publication purposes. In this case, no objections were stated.

References

- Alpers BJ (1931) Diffuse progressive degeneration of the grey matter of the cerebrum. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 25:469–505

- Blok MJ, van den Bosch BJ, Jongen E, et al. The unfolding clinical spectrum of POLG mutations. J Med Genet. 2009;46:776–785. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.067686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SS, Longley MJ, Copeland WC. The common A467T mutation in the human mitochondrial DNA polymerase (POLG) compromises catalytic efficiency and interaction with the accessory subunit. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31341–31346. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SS, Longley MJ, Naviaux RK, Copeland WC. Mono-allelic POLG expression resulting from missense-mediated decay and alternative splicing in a patient with Alpers syndrome. DNA Repair. 2005;4:1381–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Zotto E, Pezzini A, Giossi A, Volonghi I, Padovani A. Migraine and ischemic stroke: a debated question. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1399–1421. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschauer M, Tennant S, Rokicka A, et al. MELAS associated with mutations in the POLG1 gene. Neurology. 2007;68:1741–1742. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000261929.92478.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins SE, Somoza A, Gilbert DL (2010) Rare autosomal dominant POLG1 mutation in a family with metabolic strokes, posterior column spinal degeneration, and multi-endocrine disease. J Child Neurol 25:752–756 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Horvath R, Hudson G, Ferrari G, et al. Phenotypic spectrum associated with mutations of the mitochondrial polymerase gamma gene. Brain. 2006;129:1674–1684. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga Y, Ishibashi M, Ueki I, et al. Effects of L-arginine on the acute phase of strokes in three patients with MELAS. Neurology. 2002;58:827–828. doi: 10.1212/WNL.58.5.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga Y, Akita Y, Nishioka J, et al. L-arginine improves the symptoms of strokelike episodes in MELAS. Neurology. 2005;64:710–712. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000151976.60624.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga Y, Akita Y, Junko N, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in MELAS improved by l-arginine supplementation. Neurology. 2006;66:1766–1769. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000220197.36849.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga Y, Akita Y, Nishioka J, et al. MELAS and L-arginine therapy. Mitochondrion. 2007;7:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollberg G, Moslemi AR, Darin N, et al. POLG1 mutations associated with progressive encephalopathy in childhood. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:758–768. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000229987.17548.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma PT, Luo N, Löscher WN, et al. Functional defects due to spacer-region mutations of human mitochondrial DNA polymerase in a family with an ataxia-myopathy syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1907–1920. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milone M, Massie R. Polymerase gamma 1 mutations: clinical correlations. Neurologist. 2010;16:84–91. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181c78a89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montine TJ, Powers JM, Vogel FS, Radtke RA (1995) Alpers' syndrome presenting with seizures and multiple stroke-like episodes in a 17-year-old male. Clin Neuropathol 14:322–326 [PubMed]

- Naviaux RK, Nyhan WL, Barshop BA, Poulton J, Markusic D, Karpinski NC, Haas RH (1999) Mitochondrial DNA Polymerase gamma Deficiency and mtDNA Depletion in a Child with Alpers’ Syndrome. Ann Neurol 45:54–58 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Naviaux RK, Nguyen KV (2004) POLG mutations associated with Alpers' syndrome and mitochondrial DNA depletion. Ann Neurol 55:706–712 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rahman S, Hanna MG. Diagnosis and therapy in neuromuscular disorders: diagnosis and new treatments in mitochondrial diseases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:943–953. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.158279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector JT, Kahn SR, Jones MR, Jayakumar M, Dalal D, Nazarian S. Migraine headache and ischemic stroke risk: an updated meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2010;123:612–624. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JD, Tennant S, Powell H, et al. Novel POLG1 mutations associated with neuromuscular and liver phenotypes in adults and children. J Med Genet. 2009;46:209–214. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.058180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzoulis C, Engelsen BA, Telstad W, et al. The spectrum of clinical disease caused by the A467T and W748S POLG mutations: a study of 26 cases. Brain. 2006;14:1685–1692. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Goethem G, Dermaut B, Lofgren A, Martin JJ, Van Broeckhoven C. Mutation of POLG is associated with progressive external ophthalmoplegia characterized by mtDNA deletions. Nat Genet. 2001;28:211–212. doi: 10.1038/90034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong LJ, Naviaux RK, Brunetti-Pierri N, et al. Molecular and clinical genetics of mitochondrial diseases due to POLG mutations. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:E150–E172. doi: 10.1002/humu.20824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]