Abstract

Hyperargininemia is a rare autosomal recessive disorder of the last step of the urea cycle characterized by a deficiency in liver arginase1. Clinically, it differs from other urea cycle defects by a progressive paraparesis of the lower limbs (spasticity and contractures) with hyperreflexia, neurodevelopmental delay and regression in early childhood. Growth is affected as well. Hyperammonemia is episodic, if present at all. The disease is caused by mutations in the ARG1 gene; there are approximately 20 different known ARG1 mutations with considerable genetic heterogeneity. We describe two Arab siblings with a late diagnosis of hyperargininemia and present the genetic findings in their family. As ARG1 sequencing was unrevealing despite suggestive clinical and laboratory findings, molecular cDNA analysis was performed. The ARG1 expression pattern identified a 125-bp out-of-frame insertion between exons 3 and 4, leading to the addition of 41 amino acids and a premature termination codon TGA at the sixth codon downstream. The insertion originated at intron 3 and was attributable to a novel c.305 + 1323 t > c intronic base change that enabled an enhancement phenomenon. This is the first reported exon-splicing-enhancer mutation in patients with hyperargininemia. The clinical course and genetic findings emphasize the possibility that hyperargininemia causes neurological deterioration in children and the importance of analyzing the expression pattern of the candidate gene when sequencing at the DNA level is unrevealing.

Hyperargininemia (OMIM 207800) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder in the last step of the urea cycle characterized by a deficiency in liver arginase1 (EC 3.5.3.1), which normally hydrolyzes arginine into ornithine. Hyperargininemia is caused by mutations in the 8 exons of the ARG1 gene located on chromosome 6q23 (Sparkes et al. 1986). It is distinguished from other urea cycle disorders by the time of onset and the characteristic clinical picture. Hyperargininemia usually appears in infants and toddlers and rarely in the neonatal period (De Deyn et al. 1997). It manifests as progressive spastic paraparesis (less on the upper extremities), loss of developmental milestones which gradually evolves into severe mental retardation, poor growth with consequent short stature, and seizures; some patients experience episodes of irritability, nausea, poor appetite, and lethargy (Crombez and Cederbaum 2005). In neonates, hyperargininemia has been reported to present with cirrhosis (Braga et al. 1997), cholestasis (Gomes Martins et al. 2011), and cerebral edema (Picker et al. 2003). The disease usually develops insidiously; in rare cases, ammonia may rise to levels that provoke hyperammonemic crisis (Scaglia and Lee 2006). The diagnosis can be confirmed by laboratory findings of deficient arginase1 activity in erythrocytes and by molecular testing of the ARG1 gene.

We describe two siblings with hyperargininemia and present the genetic investigation of their family, which yielded a novel ARG1 mutation in an unusual site.

Material and Methods

Patient 1

A 9-year-old boy, the first child of consanguineous parents of Arabic origin, was referred to Schneider Children’s Medical Center of Israel following hospitalization in another facility because of fever of one day’s duration associated with a gradual deterioration in hepatocellular enzymes and coagulation functions. Past medical history revealed an uneventful pregnancy with birth weight 3.5 kg. The parents noticed protein aversion around the age of one year. Normal developmental milestones were achieved until age 2.5 years, when the patient began to exhibit a gradual loss of motor and verbal skills. By age 4 years, he was wheelchair-bound and had lost sphincter control. At age 5.5 years, he had two generalized tonic-clonic seizures (Table 1) with abnormal findings on electroencephalography. Magnetic resonance imaging scan was normal. Genetic consultation was noncontributory. The tentative diagnosis was cerebral palsy.

Table 1.

Main anthropometric, clinical, and metabolic characteristics of the two siblings with arginase deficiency

| Characteristics | Patient 1 | Patient 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Female |

| Age at onset/diagnosis | 2–3/9 years | 2–3/7 years |

| Anthropometric dataa | ||

| Birth weight (percentile) | 3.5 kg (50) | 3.0 kg(25) |

| Weight (percentile) | 20.2 kg (< 3) | 19.8 kg (< 3) |

| Head circumference (percentile) | 51.5 cm (9.3) | 51 cm (12) |

| Main areas of developmental deterioration and neurological manifestations | Mental, gross motor, language, sphincter control, epilepsy, hyperspasticity | Mental, gross motor, language, sphincter control, hyperspasticity |

| Blood ammonia (N 11–48 μmol/L) | ||

| At onset | 61 μmol/L | |

| At diagnosis | 123 μmol/L | 61 μmol/L |

| Arginine in plasma (N < 140 μmol/L) | 652 μmol/L | 846 μmol/L |

| Serum free carnitine (N 25–45 μmol/L) | 18.4 μmol/L | 33.0 μmol/L |

| Serum total carnitine (N 30–50 μmol/L) | 22.5 μmol/L | 43.4 μmol/L |

| CSF arginine (N < 35 μmol/L) | 107 μmol/L | 85 μmol/L |

| Urinary excretion | ||

| Orotic acid (control > 250 mmol/mol creatinine) | 401 mmol/mol creatinine | Markedly elevated |

| Uracil (control 5-36 mmol/mol creatinine) | 189 mmol/mol creatinine | Increased |

aHeight/length measurements could not be obtained because of the patients’ severe contractures

On physical examination, the patient was conscious. Severe mental retardation was noted; he could not speak and hardly responded to simple commands. No dysmorphism was noted. Vital signs were within normal range.

The liver was palpable 2 cm below the rib cage. Neurological examination revealed spasticity hyperreflexia and prominent contractures in the lower limbs (Table 1). Laboratory tests showed mild anemia and thrombocytopenia, with glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase 920 U/L, glutamic pyruvic transaminase 719 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase 74 U/L, lactic dehydrogenase 1257 U/L, international normalized ratio (INR) 1.8, creatine kinase 668 U/L, amylase 182 U/L, urea 25 mg/dL. Metabolic work-up was remarkable for high blood levels of arginine, high excretion of orotic acid in the urine, and mild to moderate hyperammonemia. Free and total carnitine levels were mildly low (Table 1). Blood citrulline, glutamine, and ornithine, blood gasses, lactate, pyruvate, and very-long-chain fatty acids were within normal limits.

The fever resolved within a few days, with gradual improvement in hepatocellular enzyme levels and INR. Arginase deficiency was presumed, and molecular investigation was performed.

Patient 2

A 7-year-old girl, the sister of patient 1, had a similar course of neurological deterioration and was therefore invited for investigation. Her anthropometric and clinical characteristics and metabolic profile are presented in Table 1.

Molecular Analysis

DNA samples of the patients, a third healthy sibling, and their parents were extracted from whole blood by standard methods. Linkage analysis was performed using microsatellite markers D6S262, D6S457, D6S413 (Fig. 1). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were analyzed on an ABI3100 genetic analyzer with Genescan software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). ARG1 was sequenced by amplifying each exon and its flanking regions. PCR products were purified and sequenced with the BigDye terminator system on an ABI prism 3700 sequencer. As ARG1 is constitutively expressed in granulocytes in addition to hepatocytes (Munder et al. 2005), RNA was extracted from freshly prepared leukocytes of the family members using the High Pure RNA isolation kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), and first-strand synthesis was performed with Superscript II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The primers used for RT-PCR and for the PCR of the identified mutation are listed in Table 2. PCR products for the mutation analysis were restricted with BspE1, which cuts the mutant allele. One hundred control alleles were tested to rule out polymorphism.

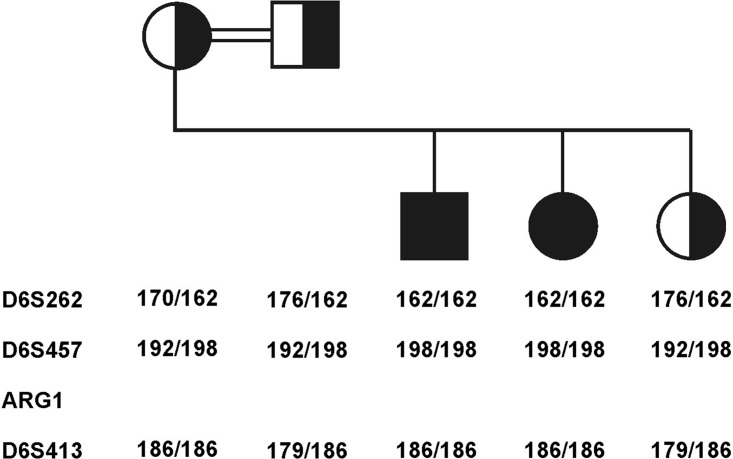

Fig. 1.

Linkage analysis of the family. The two affected children are homozygous for the same haplotype, whereas the parents and the healthy sib are heterozygous for this haplotype

Table 2.

Primers used for RT-PCR analysis of ARG1 and for PCR of the identified mutation

| Primers | |

|---|---|

| ARG1 open-reading frame | |

| Fragment A | ARG1AF 5′-TGACTGACTGGAGAGCTCAAG-3′ and ARG1AR 5′-GTCTGTCCACTTCAGTCATTG-3′ |

| Fragment B | ARG1BF 5′-TGTGTATATTGGCTTGAGAGA-3′ and ARG1BR 5′-TTGAATTTTACACCAAGAGGG-3′ |

| Identified mutation | F-5′-CCGCAATACTTTTGCACCAAC-3′ |

| R-5′-CGTATGGCGTGTGTTCACTC-3′ |

Results

Linkage analysis indicated that both affected children were homozygous for the same haplotype. The parents and healthy sib were carriers of this haplotype (Fig. 1).

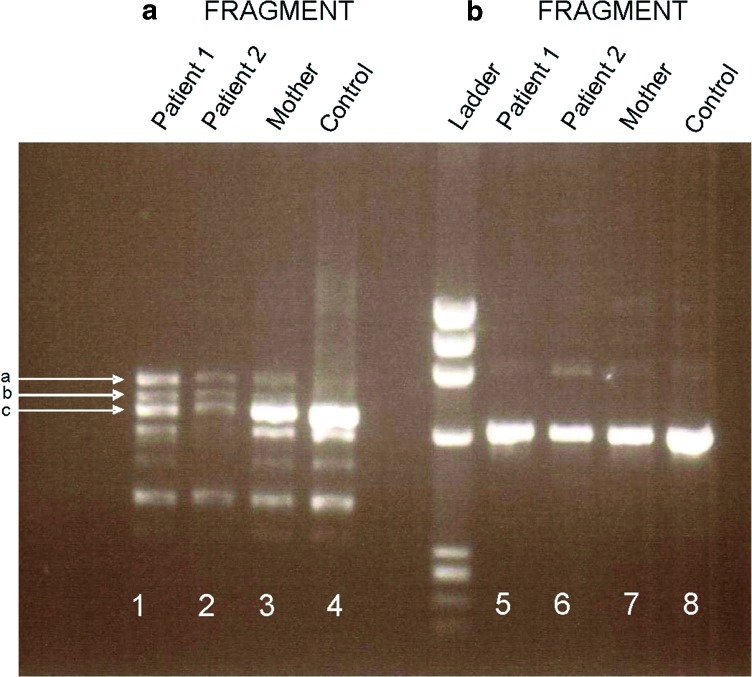

DNA sequencing of each exon of the ARG1 gene did not reveal any base change. However, RT-PCR products of fragment A of the patients (Fig. 2) showed a unique pattern: one band (c) with much weaker expression in the patients than in the mother and control despite its similar size, and two longer bands (a, b) expressed only in the patients. Sequencing of band c revealed a normal ARG1 transcript with much lower expression than in the control. The upper band (a) contained a 125-bp insertion between exons 3 and 4, leading to the addition of 41 amino acids and a premature termination codon TGA at the sixth codon downstream to the inserted fragment. Band b was a mixture of bands a and c.

Fig. 2.

RT-PCR of ARG1. Fragment A (lanes 1 and 2, affected sibs; lane 3, mother; lane 4, normal control) shows one weak band (c) at the level of the control band in lanes 1 and 2 and two bands (a, b) that are absent in the control. Band c is characterized by a normal ARG1 transcript, with much lower expression in the patients than the control. The upper band (a) contains a 125-bp insertion between exons 3 and 4, leading to the addition of 41 amino acids and a premature termination codon TGA at the sixth codon downstream. Band b is a mixture of bands a and c. Fragment B was similar in the affected sibs (lanes 5,6), their mother (lane 7), and the normal control (lane 8)

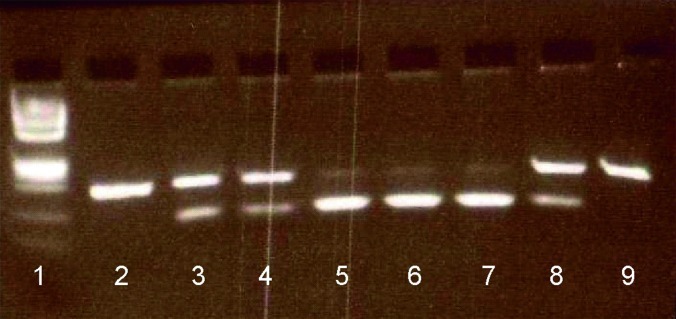

Blast analysis of the inserted fragment revealed that it originated from the third intron of the ARG1 gene, at c.305 + 1314-_1438. The intronic sequence of the insertion was flanked by the consensus splice sites, AG and GT. An intronic mutation c.305 + 1323 t > c was found at the tenth nucleotide in the inserted fragment. The patients were homozygous for this mutation, and the parents and healthy sibling were heterozygous, as shown by PCR and restriction by BspE1 (Fig. 3). The mutation was not found in the DNA of 100 controls of Arabic origin.

Fig. 3.

Restriction analysis of the ARG1 mutation c.305+1314_1438. The mutation introduces a BspE1 restriction site. Lane 1, DNA ladder; lane 2, unrestricted PCR product; lanes 3–9, restricted PCR products: lane 3 – mother, lane 4 – father, lane 8 – healthy sib showing partial restriction indicating a heterozygous genotype, lanes 5 and 6 – duplicates of patient 1 demonstrating complete restriction for a homozygous genotype; lane 7 – patient 2, lane 9 – restricted control indicating absence of restriction site

Discussion

As in previous reports of argininemia (Prasad et al. 1997; Lee et al. 2011), our patients were initially thought to have cerebral palsy, which considerably delayed the correct diagnosis. Argininemia was presumed on the basis of the characteristic disease course and clinical findings (Crombez and Cederbaum 2005) combined with the typical biochemical results (Table 1).

Because of its prenatal diagnostic advantage, molecular analysis was preferred for confirmation over the red blood cell arginase activity assay.

The novel mutation identified here is added to the approximately 20 known ARG1 mutations (http:www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk) reported in patients of different ethnic origins. These include missense, nonsense, splicing, regulatory mutations deletions and insertions. Most mutations are private. However, there is one report of a possible ethnicity-associated mutation (R21X) in four unrelated Portuguese patients (Cardoso et al. 1999).

The reported ARG1 mutations are located along the coding region of the gene (http:www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk). An association has been found between the type and site of these mutations and the structural and functional changes in the protein product (Vockley et al. 1996). Missense mutations within highly conserved regions that encodes for amino acids at the active site of arginase1 impairs enzyme function; substitution mutations outside these regions are thought to be silent with no clinical implications. By contrast, stop codon mutations and microdeletions may appear randomly along the gene and cause a truncated protein with consequently total loss of arginase1 activity (Vockley et al. 1996). We speculate that the chain-terminating mutation found in our patients generated a transcript harboring a truncated peptide leading to loss of enzyme activity.

The intronic t > c change, which was the only difference between the normal and the affected sequence, is an exon-splicing-enhancer mutation. It created a better binding site for different splicing factors that define AG and GT on both sides of the intronic inserted fragment as splice sites. Interestingly, the intronic t > c change was already noted when ARG1 DNA was initially sequenced, but at that point, it was considered to be a clinically insignificant single nucleotide polymorphism.

The finding of a normal ARG1 transcript (band c) in the patient’s lane (Fig. 2), although in a much smaller amount than in his mother's and the control lanes is not surprising given the presence of the consensus donor and acceptor sites flanking all the ARG1 exons. We believe that the reason this transcript does not prevent the disease derives from the homotrimeric composition of arginase1 (Brusilow and Horwich 2001), such that assembly of the normal protein with the mutant one does not maintain an active enzyme.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported exon-splicing-enhancer mutation in patients with hyperargininemia, and the second reported mutation in a family of Arab origin (Korman et al. 2004).

This report should alert clinicians to the possibility of missed diagnosis of hyperargininemia in children presenting with severe spastic paraparesis and mental retardation. It also highlights the significance of analyzing the expression pattern of a candidate gene if sequencing at the DNA level is unrevealing.

Take Home Message

A late diagnosis of hyperargininemia should be considered in pediatric patients with neurodevelopmental delay and regression in early childhood.

When cDNA sequencing is unrevealing, the expression pattern of the candidate gene should be analyzed for identification of potential novel mutations.

Details of Contributors

Dr. Haimi-Cohen collected and analyzed the clinical data, described the patients, and drafted and edited the manuscript.

Mrs. Bargal conducted and interpreted the molecular analysis and described the genetic findings in the manuscript.

Dr. Zeigler supervised the molecular analysis investigation and contributed significantly in interpreting the data and revising the manuscript.

Dr. Eidlitz-Markus helped in the collection and analysis of the clinical data and made a great contribution to the writing of the manuscript.

Mrs. Zuri contributed to all stages of the molecular analysis and the interpretation of its results and assisted in revising the manuscript.

Dr. Zeharia initiated the study. He contributed substantially to coordination of the clinical and molecular data of the study, to its design, and to the revision of the manuscript.

Guarantor of Study

Yishai Haimi-Cohen

Patient Consent

Not applicable

Competing Interests

None of the authors has a conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- Braga AC, Vilarinho L, Ferreira E, Rocha H. Hyperargininemia presenting as persistent neonatal jaundice and hepatic cirrhosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24:218–221. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199702000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusilow SW, Horwich AL. Urea cycle enzymes. In: Sriver CR, Baudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The metabolic bases of inherited diseases. 8. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 1909–1963. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso ML, Martins E, Vasconcelos R, Vilarinho L, Rocha J. Identification of a novel R21X mutation in the liver-type arginase gene (ARG1) in four Portuguese patients with argininemia. Hum Mutat. 1999;14:355–356. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(199910)14:4<355::AID-HUMU20>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombez EA, Cederbaum SD. Hyperargininemia due to liver arginase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;84:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Deyn PP, Marescau B, Qureshi IA, et al. Hyperargininemia: A treatable inborn error of metabolism? In: De Deyn PP, Marescau B, Qureshi IA, et al., editors. Guanidino compounds in biology and medicine. London: John Libbey & Company Ltd; 1997. pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes Martins E, Santos Silva E, Vilarinho S, Saudubray JM, Vilarinho L (2011) Neonatal cholestasis: an uncommon presentation of hyperargininemia. J Inhert Metab Dis. [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1007/s10545-10-9263-7, Jan 13 Online [DOI] [PubMed]

- Korman SH, Gutman A, Stemmer E, Kay BS, Ben-Neriah Z, Zeigler M. Prenatal diagnosis for arginase deficiency by second-trimester fetal erythrocyte arginase assay and first-trimester ARG1 mutation analysis. Prenat Diagn. 2004;24:857–860. doi: 10.1002/pd.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Jin HH, Kim GH, Choi JH, Yoo HW. Argininemia presenting with progressive spastic diplegia. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;44:218–220. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munder M, Mollinedo F, Calafat J, et al. Arginase 1 is constitutively expressed in human granulocytes and participates in fungicidal activity. Blood. 2005;105:2549–2556. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picker JD, Puga AC, Levy HL, et al. Arginase deficiency with lethal neonatal expression: evidence for the glutamine hypothesis of cerebral edema. J Pediatr. 2003;142:349–352. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad AN, Breen JC, Ampola MG, Rosman NP. Argininemia: A treatable genetic cause of progressive spastic diplegia simulating cerebral palsy: case reports and literature review. J Child Neurol. 1997;12:301–309. doi: 10.1177/088307389701200502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaglia F, Lee B. Clinical, biochemical and molecular spectrum of hyperargininemia due to arginase 1 deficiency. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2006;142C:113–120. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes RS, Dizikes GJ, Klisak I, et al. The gene for human arginase (ARG1) is assigned to chromosome band 6q23. Am J Hum Genet. 1986;39:186–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vockley JG, Goodman BK, Tabor DE, et al. Loss of function mutations in conserved region of the human arginase 1 gene. Biochem Mol Med. 1996;59:44–51. doi: 10.1006/bmme.1996.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]