A novel stage-specific surface protein, T. congolense insect-stage surface antigen (TcCISSA), from the African trypanosome T. congolense was recently identified by mass-spectrometric differential protein-expression analysis. To gain structure–function insight into this protein, the extracellular domain of TcCISSA was expressed, purified and crystallized and X-ray diffraction data were collected and processed to 2.7 Å resolution.

Keywords: Trypanosoma congolense, procyclic form, animal African trypanosomiasis, insect stage, vector–pathogen interactions, surface proteins

Abstract

Trypanosoma congolense is a major contributor to the vast socioeconomic devastation in sub-Saharan Africa caused by animal African trypanosomiasis. These protozoan parasites are transmitted between mammalian hosts by tsetse-fly vectors. A lack of understanding of the molecular basis of tsetse–trypanosome interactions stands as a barrier to the development of improved control strategies. Recently, a stage-specific T. congolense protein, T. congolense insect-stage surface antigen (TcCISSA), was identified that shows considerable sequence identity (>60%) to a previously identified T. brucei insect-stage surface molecule that plays a role in the maturation of infections. TcCISSA has multiple di-amino-acid and tri-amino-acid repeats in its extracellular domain, making it an especially interesting structure–function target. The predicted mature extracellular domain of TcCISSA was produced by recombinant DNA techniques, purified from Escherichia coli, crystallized and subjected to X-ray diffraction analysis; the data were processed to 2.7 Å resolution.

1. Introduction

African trypanosomiasis is a devastating disease caused by kinetoplastid parasites of the genus Trypanosoma. These parasites, which infect both humans and livestock, cause vast socioeconomic damage in sub-Saharan Africa, with approximately 60 million people and 50 million cattle living in areas that are infested with the infamous vector of the parasites, the tsetse fly (Glossina spp.). In addition to the estimated 30 000 new cases each year of human African trypanosomiasis (caused by T. brucei spp.), the economic losses owing to animal African trypanosomiasis amount to approximately five billion US dollars per annum (Dargie, 2011 ▶). The most economically significant species of trypanosome affecting cattle is T. congolense.

As T. congolense differentiates from the bloodstream form (BSF) in mammals to the procyclic form (PF) in the tsetse midgut, the composition of the surface coat of the parasite undergoes drastic changes. Variant surface glycoproteins (VSGs) on BSFs are replaced by a dense layer of protease-resistant molecules in early PFs; this is followed by the expression of heavily glycosylated T. congolense-specific procyclins in established tsetse-midgut infections (Utz et al., 2006 ▶). Because the insect-stage trypanosomes do not undergo antigenic variation, these stages offer an improved target for parasite control if strategies can be devised to disrupt their transmission to mammalian hosts. Unfortunately, a lack of information regarding the molecular basis of trypanosome–tsetse interactions stands as a major obstacle to the development of such strategies. Despite the identification of several major surface molecules on the insect form of T. congolense, few have proposed functionality and only one of them, glutamic acid/alanine-rich protein (GARP), has been structurally characterized (Loveless et al., 2011 ▶).

A recent proteomics study investigated differential protein expression throughout the T. congolense life cycle and revealed several previously unidentified T. congolense-specific proteins (Eyford et al., 2011 ▶). One of these was only expressed in the insect stages of the trypanosome life cycle and was named T. congolense insect-stage surface antigen (TcCISSA). Interestingly, TcCISSA shows considerable sequence identity (>60%) to a stage-specific surface antigen previously identified in T. brucei: procyclic-stage surface antigen 2 (TbPSSA-2; Jackson et al., 1993 ▶). Both TcCISSA and TbPSSA-2 are predicted to contain an N-terminal extracellular domain, a single transmembrane-spanning domain and a C-terminal cytoplasmic domain. A recent study showed that TbPSSA-2 null mutants are competent at establishing midgut infections in tsetse, but show deficiency in the colonization of the salivary glands and the transition to the infectious metacyclic forms (Fragoso et al., 2009 ▶). The authors postulated that TbPSSA-2 could be involved in sensing and transmitting signals that contribute to the decision of the parasite to divide, differentiate or migrate (Fragoso et al., 2009 ▶).

While TcCISSA is an intriguing protein based on the putative functions of its homologue in T. brucei, its extracellular domain is also interesting purely from a structure–function perspective owing to the presence of multiple di-amino-acid and tri-amino-acid repeats [DD, EE, GG, QQ, RR, SS (×3), TT, GGG, RRR, SSS (×2) and VVV] combined with a predominance of charged residues (>25%). As TcCISSA contains no identifiable domains or motifs, genetic approaches to interpretation of functional data would be hindered. In the studies reported here, we undertook a structural approach to identify features of the N-terminal extracellular domain of TcCISSA that may aid in elucidation of how TcCISSA interacts with the tsetse vector. By defining the role of TcCISSA in the trypanosome life cycle, it may be possible to devise strategies for interference in the T. congolense life cycle, thus preventing disease transmission.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Construct design and cloning of TcCISSA

The sequence corresponding to TcCISSA from T. congolense IL3000 was obtained from TriTrypDB (Aslett et al., 2010 ▶; accession No. TcIL3000.10.9440). The N-terminal extracellular domain (TcCISSAn) was synthesized by GenScript and cloned NcoI–NotI into a modified pET32a vector (Novagen). The construct contained N-terminal thioredoxin and hexahistidine tags separated from TcCISSAn by a thrombin-cleavage site. The TcCISSAn construct aligns with the predicted start of the mature extracellular domain of TbPSSA-2 (Jackson et al., 1993 ▶) and extends through to the start of the predicted transmembrane helix. Sequencing confirmed that no mutations were introduced during the amplification procedures.

2.2. Expression and purification of TcCISSAn

TcCISSAn was produced by recombinant expression in Escherichia coli Rosetta-gami 2 (DE3) cells (Novagen) grown from a 5% inoculum in ZYP-5052 auto-induction medium with 40 µg ml−1 chloramphenicol and 60 µg ml−1 ampicillin. Following growth for 4 h at 310 K and 64 h at 289 K, the cells were harvested by centrifugation and the pellet was resuspended in 10 mM Tris pH 8.5, 1 M NaCl, 30 mM imidazole. Resuspended cells were lysed using a French press and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation. The soluble fraction was incubated with Ni-chelated Sepharose beads for 1 h at 277 K. Bound TcCISSAn was eluted with 10 mM Tris pH 8.5, 1 M NaCl, 250 mM imidazole. The thioredoxin and hexahistidine tags were removed by thrombin cleavage overnight at 291 K in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) with 2.25 mM calcium chloride and the sample was purified by gel-filtration chromatography on a Superdex 75 16/60 HiLoad column (GE Healthcare) in TBS. Fractions containing monomeric TcCISSAn were pooled and further purified by cation-exchange chromatography on a HiTrap SP FF column (GE Healthcare) in 20 mM HEPES pH 6.8, 10 mM NaCl. TcCISSAn was eluted with an increasing concentration of NaCl and the pooled fractions were concentrated to 25 mg ml−1 in TBS using Amicon Ultra (Millipore) centrifugal filter devices. The purity of TcCISSAn was determined by SDS–PAGE at each stage and protein concentrations were analyzed by the absorbance at 280 nm based on an extinction coefficient of 29 380 M −1 cm−1.

2.3. Crystallization, data collection and processing

Initial crystallization trials for TcCISSAn were set up using commercial screens (Wizard I and II from Emerald BioSystems and Crystal Screen, Crystal Screen 2 and PEG/Ion from Hampton Research) in 96-well Intelli-Plates (Hampton Research) using a Crystal Gryphon (Art Robbins Instruments). Two protein:reservoir solution ratios were explored in sitting drops consisting of 0.2 or 0.3 µl protein solution (25 mg ml−1 in TBS) and 0.2 µl reservoir solution and equilibrated against 55 µl reservoir solution. A single crystal form of TcCISSAn was observed in 20% PEG 3350 with 0.2 M ammonium sulfate after overnight incubation at 291 K; the crystals developed equally well using both drop ratios.

A single TcCISSAn crystal was looped, stepped into a final cryoprotectant consisting of reservoir solution supplemented with 25% glycerol and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected on beamline 7-1 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) using an ADSC Quantum 315r CCD detector. Overall, 320 images were collected with 0.5° oscillation and selected data were processed to 2.7 Å resolution. Diffraction data for TcCISSAn were processed using iMOSFLM (Battye et al., 2011 ▶) and AIMLESS from the CCP4 suite of programs (Winn et al., 2011 ▶). Data-collection and processing statistics are presented in Table 1 ▶.

Table 1. Data-collection and processing statistics for TcCISSAn.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Space group | P212121 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 58.80, b = 83.42, c = 182.76, α = β = γ = 90 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.1271 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 60.92–2.70 (2.83–2.70) |

| Measured reflections | 89371 |

| Unique reflections | 24608 (3207) |

| Multiplicity | 3.6 (3.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.1 (96.1) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 10.9 (2.0) |

| R merge † | 0.055 (0.400) |

R

merge =

, where 〈I(hkl)〉 is the average of symmetry-related observations of a unique reflection.

, where 〈I(hkl)〉 is the average of symmetry-related observations of a unique reflection.

3. Results and discussion

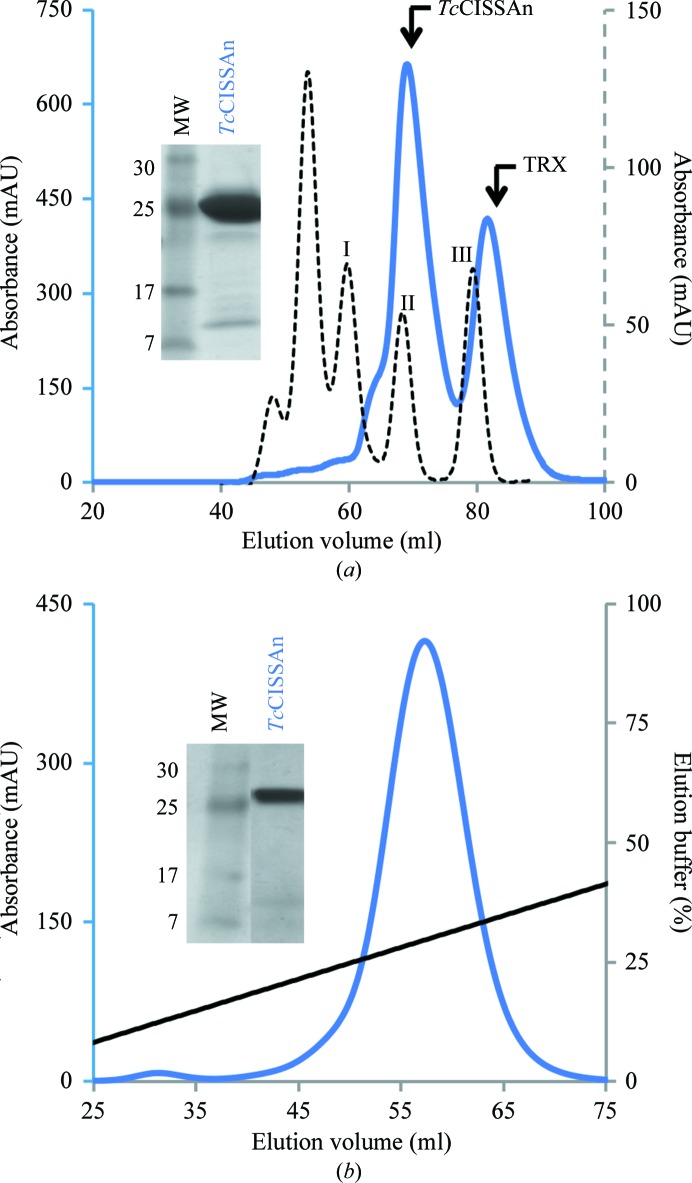

DNA encoding the N-terminal extracellular domain of TcCISSA (TcCISSAn) was synthesized and the protein was expressed in E. coli, purified to homogeneity and successfully crystallized. Since the 225-residue construct of TcCISSA is of eukaryotic origin and includes eight cysteine residues predicted to form four disulfide bonds, two techniques were combined to obtain soluble properly folded protein. Firstly, Rosetta-gami 2 (DE3) cells were utilized for their supplemental tRNAs that overcome typical E. coli codon bias and for their less reducing cytoplasmic environment. Secondly, a thioredoxin tag was fused to the N-terminus of TcCISSAn to enhance the correct disulfide-bond formation. Following the cleavage of TcCISSAn from its fusion tag, gel-filtration chromatography showed that it eluted as a single monomeric peak in comparison to a set of globular standards (Fig. 1 ▶ a). However, residual thioredoxin co-eluted with TcCISSAn (Fig. 1 ▶ a, inset), necessitating a cation-exchange chromatography step to obtain sufficiently pure TcCISSAn suitable for crystallization (Fig. 1 ▶ b).

Figure 1.

(a) Purification of TcCISSAn by gel-filtration chromatography on a Superdex 75 16/60 HiLoad column. Standards for gel-filtration chromatography (plotted against the secondary axis, dotted curve): peak I, ovalbumin (43 kDa); peak II, carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa); peak III, ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa). TcCISSA (solid blue curve) eluted as a monomer. Inset: SDS–PAGE analysis of a representative fraction showing migration at the expected molecular mass of 26 kDa and residual thioredoxin tag. Lane MW contains molecular-mass markers (labelled in kDa). (b) Further purification of TcCISSAn by cation-exchange chromatography on a 5 ml HiTrap SP FF column. Inset: SDS–PAGE analysis of a representative fraction showing refined sample free of residual thioredoxin tag.

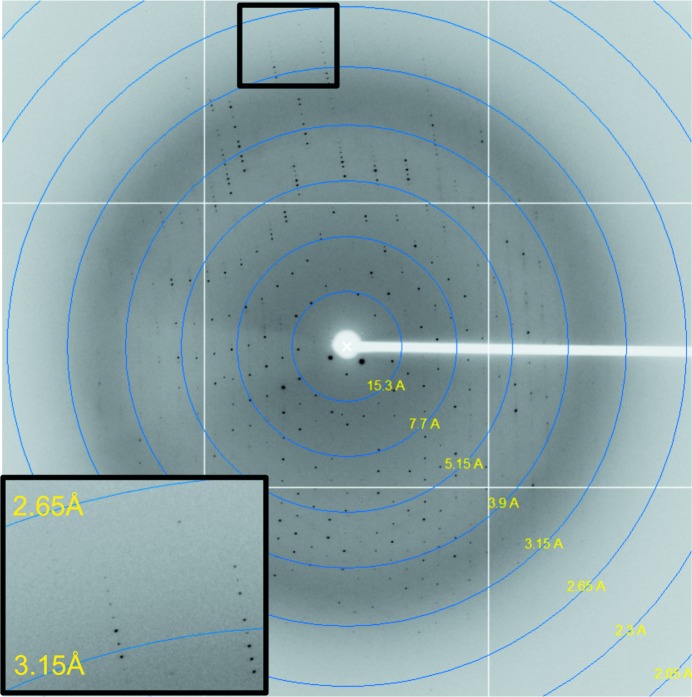

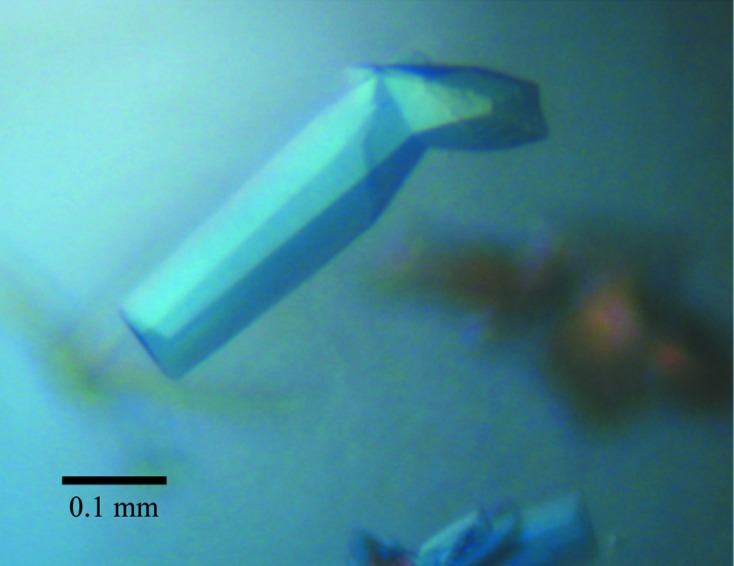

Crystallization trials of TcCISSAn yielded fused clusters of thick crystal plates that grew to maximum dimensions of approximately 0.1 × 0.35 × 0.05 mm (Fig. 2 ▶). Dissected single plates diffracted to a maximum resolution of 2.7 Å on beamline 7-1 at SSRL, with an average mosaicity of 0.52° (Fig. 3 ▶). Processing of these data revealed that TcCISSAn crystallized in a primitive orthorhombic unit cell (space group P212121); the Matthews coefficient with the highest probability was 2.15 Å3 Da−1, corresponding to four molecules in the asymmetric unit and a solvent content of 42.71% (Matthews, 1968 ▶). Scaling and merging of the data resulted in an overall R merge of 5.5% (40.0% in the highest resolution shell).

Figure 2.

TcCISSAn crystals grown in a sitting drop with 20% PEG 3350, 0.2 M ammonium sulfate as the reservoir solution.

Figure 3.

X-ray diffraction image from a TcCISSAn crystal. Inset, high-resolution area; data were processed to 2.7 Å resolution.

Despite extensive searches, no suitable templates for molecular replacement were identified for TcCISSAn. The presence of only a single methionine in the 225-residue construct limits the likelihood that a selenomethionine-derivatization approach will produce phases of sufficient quality to solve the structure. Consequently, we are currently pursuing halide soaks, as well as selenomethionine/selenocysteine dual-labelling phasing strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Discovery Research grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to TWP and MJB. MJB is a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) Scholar and a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair. MLT was supported by an NSERC Alexander Graham Bell Canada Graduate Scholarship (CGSD3) and BAE was supported by an NSERC Postgraduate Fellowship. The authors gratefully acknowledge the staff at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL).

References

- Aslett, M. et al. (2010). Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D457–D462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Battye, T. G. G., Kontogiannis, L., Johnson, O., Powell, H. R. & Leslie, A. G. W. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dargie, J. (2011). Editor. Tsetse and Trypanosomosis Information, Vol. 34, pp. 1–132. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Eyford, B. A., Sakurai, T., Smith, D., Loveless, B., Hertz-Fowler, C., Donelson, J. E., Inoue, N. & Pearson, T. W. (2011). Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 177, 116–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fragoso, C. M., Schumann Burkard, G., Oberle, M., Renggli, C. K., Hilzinger, K. & Roditi, I. (2009). PLoS One, 4, e7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D. G., Smith, D. K., Luo, C. & Elliott, J. F. (1993). J. Biol. Chem. 268, 1894–1900. [PubMed]

- Loveless, B. C., Mason, J. W., Sakurai, T., Inoue, N., Razavi, M., Pearson, T. W. & Boulanger, M. J. (2011). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 20658–20665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Utz, S., Roditi, I., Kunz Renggli, C., Almeida, I. C., Acosta-Serrano, A. & Bütikofer, P. (2006). Eukaryot. Cell, 5, 1430–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.