The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway is mutated in approximately half of tumors; it is therefore important to define its functions. This study shows that PI3Kα activity regulates mitotic entry and spindle orientation; in contrast, PI3Kβ controls dynein/dynactin and Aurora B activation at kinetochores and, in turn, chromosome segregation.

Abstract

Class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K) are enzymes composed of a p85 regulatory and a p110 catalytic subunit that control formation of 3-poly-phosphoinositides (PIP3). The PI3K pathway regulates cell survival, migration, and division, and is mutated in approximately half of human tumors. For this reason, it is important to define the function of the ubiquitous PI3K subunits, p110α and p110β. Whereas p110α is activated at G1-phase entry and promotes protein synthesis and gene expression, p110β activity peaks in S phase and regulates DNA synthesis. PI3K activity also increases at the onset of mitosis, but the isoform activated is unknown; we have examined p110α and p110β function in mitosis. p110α was activated at mitosis entry and regulated early mitotic events, such as PIP3 generation, prometaphase progression, and spindle orientation. In contrast, p110β was activated near metaphase and controlled dynein/dynactin and Aurora B activities in kinetochores, chromosome segregation, and optimal function of the spindle checkpoint. These results reveal a p110β function in preserving genomic stability during mitosis.

INTRODUCTION

Cell division begins when quiescent cells bind growth factors through specific cell membrane receptors. Class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K) are a subclass of signaling molecules that regulate cell cycle entry; the PI3K pathway has been found to be mutated in approximately half of human tumors and is considered a promising target for cancer treatment (Liu et al., 2009). PI3K comprises a p85 regulatory and a p110 catalytic subunit that trigger formation of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate (PIP3). Of the three class IA catalytic subunits (p110α, β, and δ), p110α and p110β are ubiquitous and regulate cell division. In contrast, p110δ is more abundant in hematopoietic cells and controls the immune response (Fruman and Cantley 2002; García et al., 2006). PI3K is activated after growth factor addition to quiescent cells and triggers progression throughout the G1 phase. PI3K is activated again at the G1-S border, promoting DNA synthesis, and is again activated at the G1-S transition, controlling mitotic entry (Jones and Kazlauskas 2001; Dangi et al., 2003; García et al., 2006; Marqués et al., 2009).

Mitosis begins when nuclear cyclin B binds to and activates Cdk1, which phosphorylates many substrates that regulate mitotic entry, including cytoskeletal components that trigger cell rounding (Cukier et al., 2007). In mitotic prophase, cells contact the extracellular matrix through β1-integrin receptors that activate Src and PI3K; the PI3K product PIP3 concentrates at the cell midcortex and regulates dynein/dynactin recruitment and spindle orientation (Toyoshima et al., 2007). Dynein/dynactin is a minus-end microtubule (MT) motor protein complex that controls execution of various mitotic events. It localizes to the cell cortex in metaphase, where it regulates spindle orientation, but also concentrates in prometaphase kinetochores (KTs), where it controls chromosome congression and movement. Dynein/dynactin dissociates from KT following MT attachment to regulate the release of spindle assembly checkpoint proteins (Busson et al., 1998; O'Connell and Wang, 2000; King et al., 2000; Yang et al., 2007).

Correct chromosome segregation is controlled by the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), which ensures that anaphase takes place only when all chromatid pairs have achieved bipolar attachment to MT. The spindle checkpoint machinery thus generates a delay in mitotic progression, allowing time for repair of potential MT-KT attachment defects (Yu, 2002). Although the mechanisms underlying SAC inhibitory action are only partially understood, it is accepted that a single unattached KT generates a signal that inactivates Cdc20, a cofactor of the anaphase-promoting complex that degrades securin to permit anaphase entry (Musacchio and Salmon 2007; Tanaka, 2008). KT-bound mitotic arrest–deficient proteins 1 and 2 (Mad1/Mad2) regulate Cdc20 action; modification of the SAC proteins Bub1, BubR1, and Mad2 also affect the SAC. In metazoans, the SAC has additional components (RZZ, Zwint1, CenpE, CenpI, and CenpF). Moreover, protein complexes that control KT-MT linkages, such as Aurora B and Ndc80, also regulate the SAC. Whereas the Ndc80 complex controls end-on KT-MT attachments, Aurora B corrects syntelic and merotelic KT-MT attachments (Chan and Yen 2003; McCleland et al., 2003; Vorozhko et al., 2008; Gregan et al., 2011; Santaguida et al., 2011). Inhibition of Aurora B induces accumulation of cells with incorrect KT-MT attachments that progress to anaphase with lagging chromosomes (Murata-Hori and Wang, 2002; Murata-Hori et al., 2002).

Generalized inhibition of PI3K has been reported to impair PIP3 and dynein/dynactin localization to the cell midcortex and spindle orientation (Toyoshima et al., 2007). Nonetheless, which of the two ubiquitous isoforms (p110α or p110β) regulates mitosis and whether PI3K regulates later mitotic events is not known. We examined p110α and p110β function in mitosis.

RESULTS

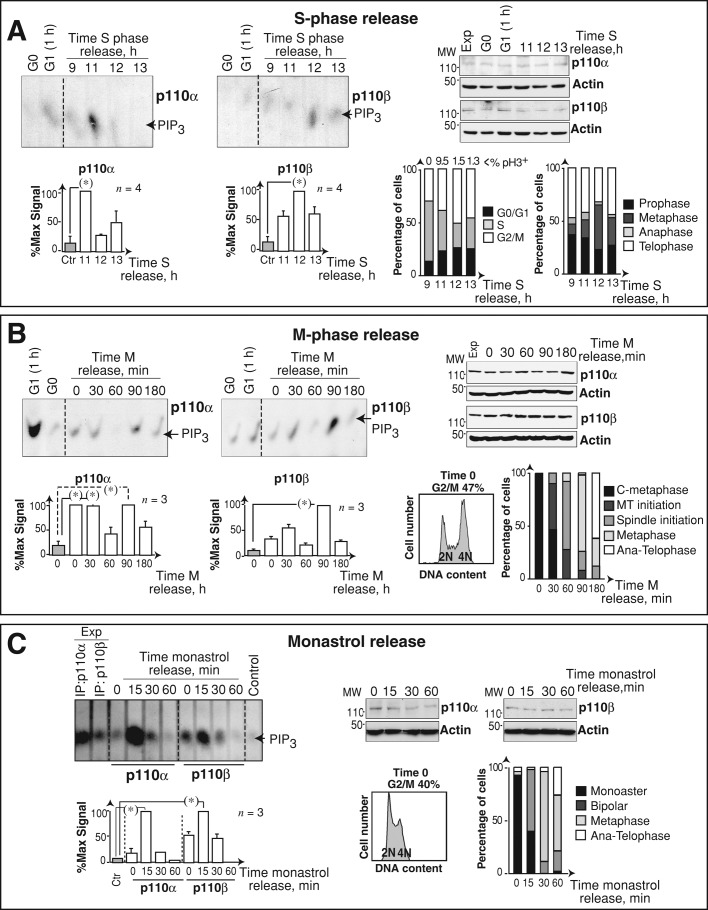

p110α and p110β are activated with distinct kinetics during mitosis

We analyzed PI3K isoform activation at the onset of mitosis using aphidicolin S phase–synchronized U2OS cells. At different times after aphidicolin removal, we examined mitotic progression by flow cytometry, measuring DNA content and phosphohistone H3 (pH3; Nigg, 1995); we also determined the proportion of cells in different mitotic phases by immunofluorescence (IF; Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure S1A). Endogenous p110α and p110β were purified using specific antibodies, and their in vitro kinase activity was tested. p110α activity increased at mitotic entry (11 h) and decreased thereafter (Figure 1A). As in other transformed cells (Shtivelman et al., 2002), p110α activation at M-phase entry was higher than at G1 entry. We quantitated p110α and p110β activity at each time point relative to their respective maximum values in mitosis (Figure 1A). p110β activity also fluctuated in mitosis and was maximal at 12 h, when cultures were enriched in metaphase cells (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1:

p110α and p110β have distinct activation kinetics during mitosis. (A) U2OS cells were blocked in S phase (10 μg/ml aphidicolin, 19 h), then released in medium for different times, or were incubated without serum (19 h; G0); some cells were serum-stimulated (1 h; G1). p110α and p110β were immunopurified, and kinase activity was assayed in vitro using phosphatidylinositol (4,5)P2 as substrate. Graphs (bottom) show signal intensity of the PIP3 spot relative to maximum signal for p110α or p110β (100%, n = 3). Right, β-actin, p110α, and p110β Western blot controls; Exp, exponential growth. Bar graphs (right) show the percentage of cells in distinct cell cycle or mitotic phases; the percentage of pH3-positive (pH3+) cells is indicated. (B) NIH 3T3 cells were arrested in metaphase using Colcemid (75 ng/ml, 12 h) and subsequently released in fresh medium for different times; kinase assay and graphs are as in (A) (n = 3). Right, β-actin, p110α, and p110β Western blot controls. The propidium iodide profile shows the accumulation of cells in G2/M cells after Colcemid treatment. Bar graphs (right) as in (A). C, Colcemid; MT, microtubule; Ana-telophase, anaphase plus telophase. (C) U2OS cells were incubated with monastrol (100 μM, 4 h), then in fresh medium for different times and processed as in (A); graphs are as in (A) (n = 3). Right, β-actin, p110α, and p110β Western blot controls. Propidium iodide profile shows cell cycle arrest after monastrol treatment. Bar graphs (right, as in A) show mitotic cells at indicated phases. Chi-square test: *, p < 0.05 (A); Student's t test: *, p < 0.05 (B).

We confirmed that p110α was the isoform activated at M entry using PIK75, a p110α inhibitor, or TGX-221 to inhibit p110β (Marqués et al., 2009). At the doses used, PIK75 selectively inhibited p110α, and TGX-221 inhibited p110β (Marqués et al., 2009). We performed PI3K assays in immunoprecipitates of the p85 regulatory subunit (which forms complexes with p110α or p110β) in the presence of inhibitors. Whereas PIK75 more markedly reduced PI3K activity at M entry (11 h), TGX-221 moderately reduced PI3K activity at a later time (12 h; Figure S1B). These results confirmed p110α as the principal isoform activated at M-phase entry, prior to p110β activation.

To confirm the distinct activation patterns of p110α and p110β in mitosis in a different cell type, we synchronized immortalized normal fibroblasts (NIH 3T3 cells) by MT depolymerization with Colcemid, which induces cell accumulation at Colcemid-blocked metaphase (C-metaphase; prometaphase-like cells); this was followed by release in fresh medium to allow synchronous M-phase progression (Figures 1B and S1C). p110α activity was high at C‑metaphase and at 30 min after Colcemid release (Figure 1B); PI3K activity at M entry was lower than at G1 entry, as observed in normal cells (Figure 1B; Álvarez et al., 2001; Marqués et al., 2008). p110α activity subsequently decreased (at 1 h) and increased again at 90 min, when the majority of the cells were in metaphase (Figure 1B). p110β activity also fluctuated in mitosis, with maximal activity at 90-min postrelease in metaphase-enriched cultures (Figure 1B). p110α and p110β activity decreased at the end of mitosis (Figure 1B, 180 min).

We also examined p110α and p110β activation in mitosis after synchronization of the cells with monastrol, which promotes prometaphase arrest–inducing accumulation of cells with monoaster spindles. At different times postrelease, U2OS cultures were enriched in cells with monoasters, short bipolar spindles, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase (Figure S1D; Kapoor et al., 2000). Kinase assays in extracts of these cells confirmed the earlier activation of p110α, as this isoform peaked at 15 min postrelease (bipolar prometaphase), while p110β activation was more maintained (Figure 1C). p110α was thus activated at mitotic entry and metaphase, whereas p110β maximal activity was found in cultures enriched in metaphase cells.

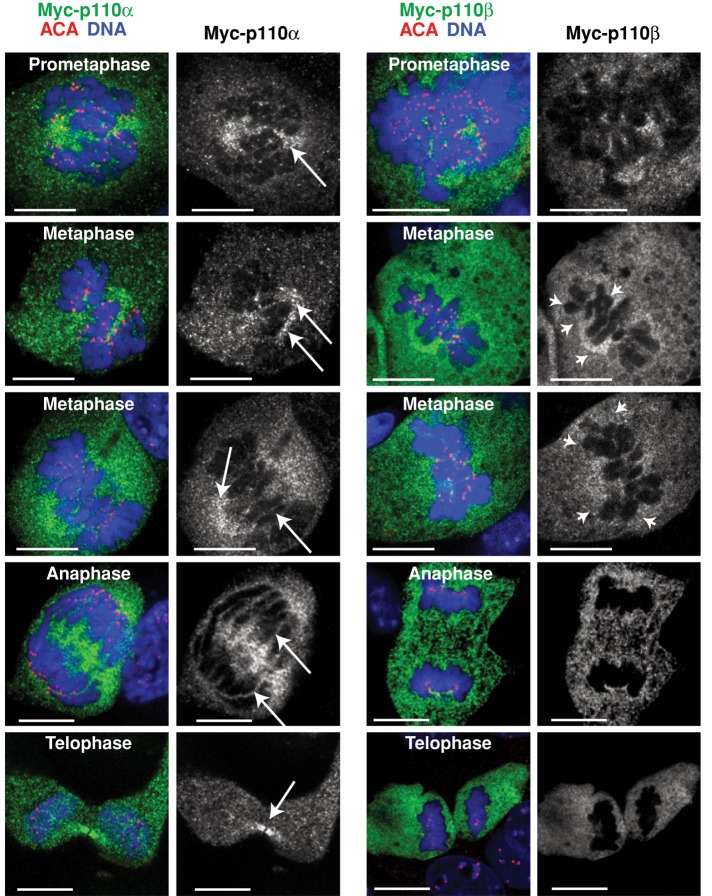

p110α and p110β localization in mitosis

Because p110α and p110β showed distinct activation kinetics in mitosis (Figure 1), we used IF to test whether their subcellular distribution also differed. We analyzed the IF signal using p110α- and p110β-specific antibodies (Marqués et al., 2009), as well as the IF signal in cells transfected with Myc-tagged-p110α or Myc-tagged-p110β using anti–Myc tag antibody (Ab). Simultaneous staining of p110, DNA and CenpA (located at kinetochores) showed Myc-p110α and Myc-p110β signals diffused throughout the cell (Figure 2). Nonetheless, whereas a fraction of endogenous or recombinant p110α selectively stained the mitotic spindle or spindle pole structures and localized at the midbody in telophase (as confirmed by simultaneous staining with α-tubulin), a fraction of p110β accumulated around DNA (Figures 2 and S2).

FIGURE 2:

p110α and p110β show distinct localization during mitosis. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with Myc-tagged p110α or p110β (48 h). Cells were fixed and immunostained using anti-Myc and anti-ACA antibodies; DNA was Hoechst 33258 stained. Representative images (in similar microscope settings) of the different mitotic phases. Scale bars: 5 μm. Arrows indicate p110α localization in mitotic spindle, spindle pole, or midbody; arrowheads indicate p110β localization near DNA.

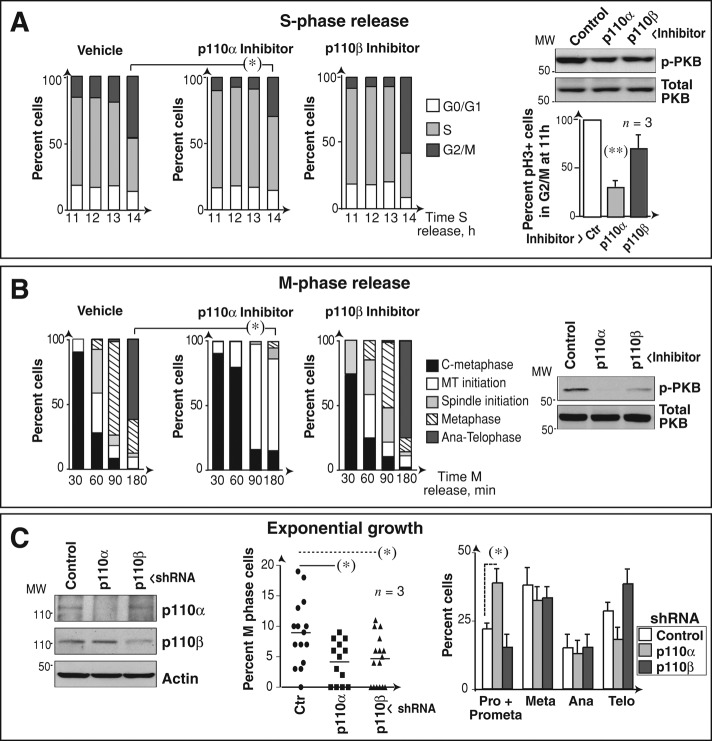

p110α activity is needed for progression through prometaphase

To determine whether inhibition of p110α or p110β affects mitotic progression independently of p110 function in earlier cell cycle phases (Marqués et al., 2008), we arrested U2OS cells in S phase and inhibited p110α or p110β at 10 h after release, prior to cell transition to G2/M phases. We used specific inhibitors as above, and confirmed that inhibitors were active, as they reduced cellular levels of the phosphorylated form of the PI3K effector protein kinase B (p-PKB; Figure 3A). In addition, p110α inhibitor, but not p110β inhibitor, significantly reduced the proportion of cells in G2/M and that of pH3+ cells (Figure 3A). Synchronization of cells in M phase (with Colcemid) followed by acute inhibition at release confirmed that p110α inhibition delayed cells in early mitosis, whereas p110β inhibition did not (Figure 3B). We also used specific short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) to test the effect of reducing p110α or p110β expression in mitosis. Both shRNAs reduced the proportion of mitotic cells, as predicted from p110α and p110β regulation of earlier cell cycle events (Marqués et al., 2008, 2009); nonetheless, examination of the mitotic stage at which cells accumulate following p110α or p110β knockdown (as in Figure S1) showed that only p110α depletion induced cell accumulation in prometaphase (Figure 3C). p110α activity is thus needed for mitotic entry and progression through prometaphase.

FIGURE 3:

Interference with PI3K causes mitotic progression defects. (A) U2OS cells were arrested with aphidicolin (10 μg/ml, 19 h) and released in fresh medium for different times. p110α or p110β inhibitors (0.5 μM PIK75 or 30 μM TGX221, respectively) were added at 10 h postrelease. Cell cycle phases were analyzed by flow cytometry and are represented in bar graphs. pPKB levels at 11 h were tested with Western blotting. The graph at the right shows the percentage of pH3+ cells in G2/M compared with maximum (100% in controls). Mean ± SD (n = 3). (B) U2OS cells were Colcemid-arrested in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide or PI3K inhibitors (as in A) for the last 3 h. Graphs show the percentage of cells in different mitotic phases at distinct times post-Colcemid withdrawal; phases were examined by DNA staining and IF using anti–α-tubulin antibody. Mean ± SD (n = 3). (C) U2OS cells were transfected with control, p110α, or p110β shRNA (48 h), and p110 levels were analyzed with Western blotting. Graphs indicate the percentage of mitotic cells in exponential growth and, of these, the percentage of cells in each phase (right) determined as in (B). Student's t test: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

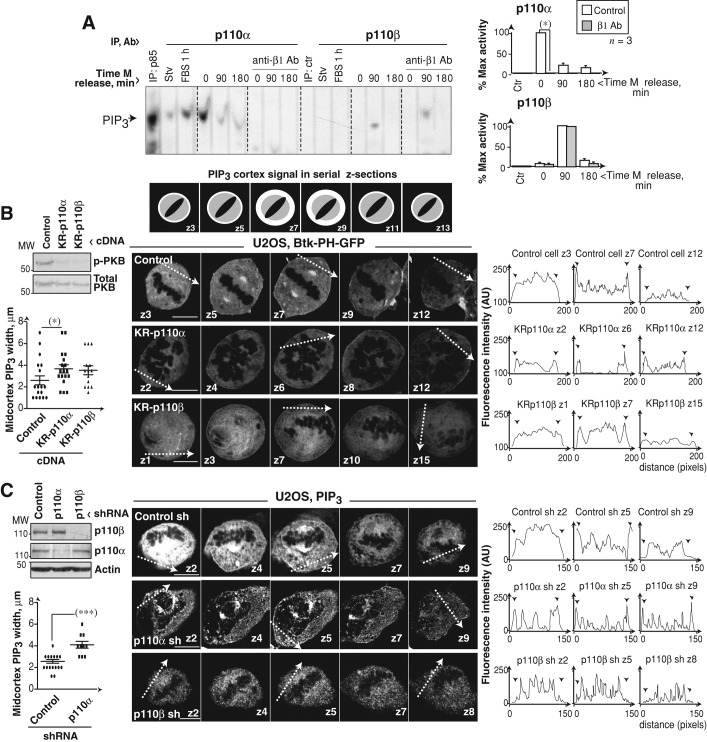

p110α activity controls PIP3 midzone localization

Prophase/prometaphase cells contact the extracellular matrix through β1-integrin receptors that promote PI3K activation and subsequent PIP3 concentration at the cell midcortex; nonspecific PI3K inhibition reduces and disperses midcortex PIP3 (Toyoshima et al., 2007). We used an anti–β1-integrin-blocking Ab to assess the effect of inhibiting these receptors on p110α and p110β mitotic activation. Blockade of β1-integrin receptors during Colcemid arrest and release (Figure 4A; or only after release, Figure S3A) abolished p110α activity.

FIGURE 4:

Interference with PI3K reduces midcortex PIP3. (A) U2OS cells were Colcemid-arrested (75 ng/ml, 12 h) and treated with Lia1/2 mAb (100 μg/ml) during and after Colcemid treatment. p110α and p110β were immunopurified and their activity assayed using phosphatidylinositol (4,5)P2 as substrate. Graphs show PIP3 signal intensity relative to maximum p110α or p110β activity (100%, n = 3). (B) Scheme (top) depicts the serial z-sections required to visualize central cortex PIP3 (white). Representative z-sections (0.5 μm) showing PIP3 localization in U2OS cells transfected with GFP-Btk-PH and KR-p110α or KR-p110β (48 h). Graphs (left) show the width (μm) of the midcortical PIP3 (mean ± SD). Western blotting shows p-PKB and PKB levels. Graphs (right) show fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units (AU, pixels) examined along the tracks indicated in the images. Arrowheads indicate cell membrane. (C) IF examination of control, p110α, or p110β knocked-down U2OS cells using specific anti-PIP3 antibody. Analysis was as in (B) z-sections (1 μm). Scale bar: 5 μm. Student's t test: *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001.

To analyze the effect of interfering with p110α or p110β activity on midcortex PIP3, we transfected cells with inactive K802R-p110α or K805R-p110β mutants combined with the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-fused Btk–pleckstrin homology (Btk-PH) domain, which binds selectively to PIP3 (Saito et al., 2001). We examined Btk-PH localization in serial z-sections by IF (scheme in Figure 4B). Both KR-p110 mutants decreased cell p-PKB (Figure 4B) and reduced the percentage of cells with cortical PIP3 by ∼20%. Nonetheless, whereas in control cells, PIP3 signal intensity in central z‑sections (z5–z7) was higher than that in distal z-sections (z1– z 2 or z9– z 12), indicating PIP3 concentration at the midcortex, in KR-p110α cells, the cortical signal was lower but maintained in central and distal z-sections, increasing the width of cortical PIP3 (Figure 4B). KR-p110β–expressing cells only showed a moderate increase in midcortex PIP3 (Figure 4B).

U2OS cells were also treated with p110α or p110β inhibitors, and PIP3 localization was analyzed using a PIP3-specific Ab (Kumar et al., 2010). Inhibition of p110α decreased PIP3 signal to background levels in ∼60% of the cells; in cells with remaining PIP3 signal, inhibition of p110α, but not of p110β, broadened the cortical PIP3 belt (Figure S3B). We also depleted p110α or p110β with shRNA. p110β shRNA moderately reduced the cellular PIP3 signal; however, most p110β knocked-down cells showed no PIP3 at the cell membrane in any z-section (Figure 4C). p110α depletion reduced PIP3 levels in more than half of the cells; in the remainder, p110α silencing increased the width of cortical PIP3 (Figure 4C). These results show that although p110β expression facilitates PIP3 recruitment to the membrane, p110β activity does not contribute to PIP3 concentration at the midcortex. In contrast, p110α is the main isoform activated by β1-integrin receptors that controls metaphase PIP3 levels and its concentration at the cell midcortex.

p110α activity controls spindle orientation

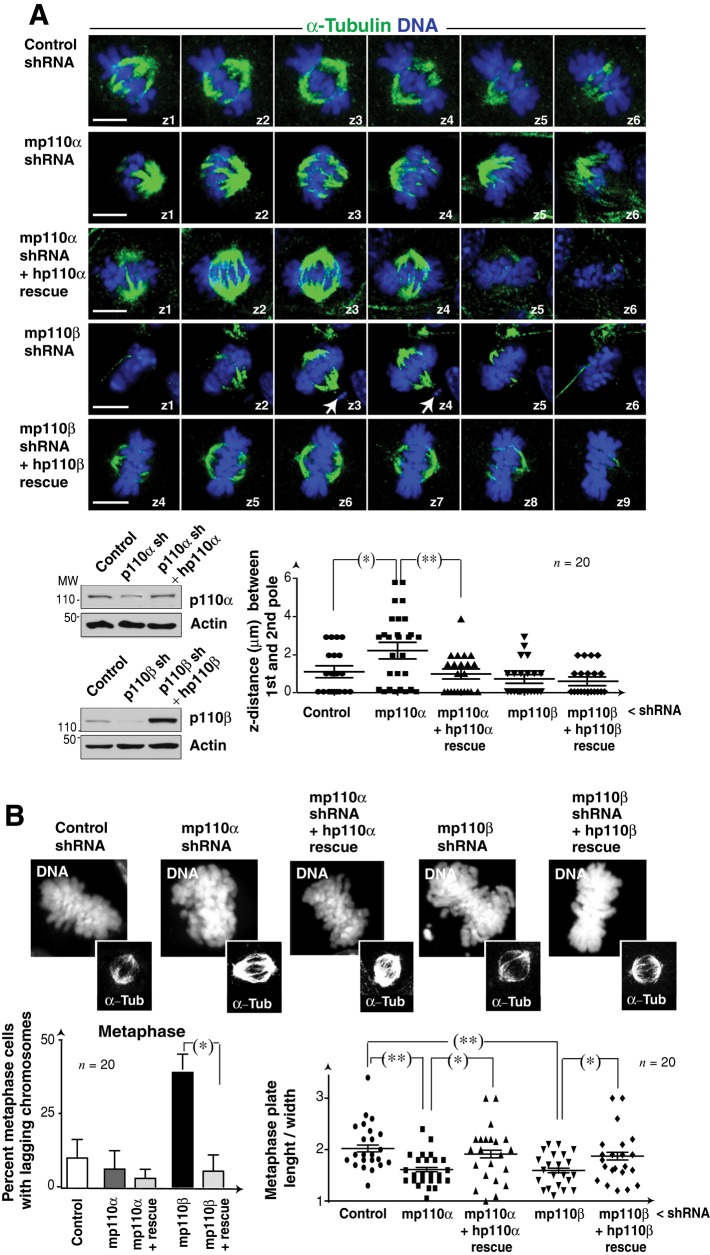

To study spindle orientation, we used U2OS and NIH 3T3 cells transfected with p110α- or p110β-specific shRNA (48 h). We analyzed whether the mitotic spindle was parallel to the adhesion plane in metaphase cells, using IF detection of α-tubulin and DNA. We found no significant differences in x-y–axis spindle length between control and knocked-down cells (Figure S4A). In control and p110β-depleted cells, both spindle poles appeared in the same z-section, showing that the spindle is parallel to the adhesion plane, however, in cells with reduced p110α levels, the two spindle poles appeared in distal z-sections, indicating that the spindle is rotated (Figures 5A and S4A). The cell requirement for p110α activity for spindle position was confirmed in U2OS cells treated with isoform-specific inhibitors or expressing KR-p110α (unpublished data). We also confirmed the selective function of p110α in regulation of spindle orientation in murine NIH 3T3 cells depleted of p110α or p110β with shRNA and reconstituted with human isoforms. p110α depletion–induced spindle orientation defects were corrected by reexpression of p110α (shRNA-resistant; Figure 5A).

FIGURE 5:

Interference with p110α produces spindle rotation. (A) NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with control, p110α, or p110β shRNA alone or in combination with plasmids encoding shRNA-resistant human p110α or p110β (48 h). Representative z-sections (1 μm) of metaphase cells stained with anti–α-tubulin Ab (green) and Hoechst 33258 (blue). Cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting. Graph shows the z-distance between poles (μm). (B) NIH 3T3 cells were transfected as in (A). Representative images showing metaphase cells labeled with Hoechst 33258 (DNA) and α-tubulin Ab (α-Tub). Bar graph (left) shows the percentage of metaphase cells with lagging chromosomes (n = 20 cells in three assays). Graph (right) indicates length/width ratio of metaphase plates; each dot represents an individual cell. Scale bar: 5 μm. Student's t test: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

In the course of these analyses, we observed that p110β depletion, but not its inhibition (unpublished data), induced defects in metaphase plate congression. Whereas metaphase plates in control cells had a length:width ratio of 2:3, p110β silencing altered metaphase plate morphology, reducing the length:width ratio (Figures 5A and S4B). In addition, a significant percentage of U2OS p110β-depleted cells had multipolar spindles and lagging chromatids in metaphase (Figure S4B). p110α depletion (Figure S4B) or inhibition (unpublished data) also altered the metaphase plate (an effect that could be secondary to spindle rotation) but did not induce lagging chromatids (Figures 5A and S4B). We confirmed the specificity of p110β depletion in the induction of chromosome segregation defects in NIH 3T3 cells; the lagging chromatids observed after p110β knockdown were corrected by reexpression of shRNA-resistant p110β (Figure 5B).

p110β depletion induces chromosomal alignment and segregation defects

Based on these data, the principal function of p110α would be to control PIP3 levels in a kinase-dependent manner, as its inhibition or deletion provoked similar defects. In contrast, p110β deletion induced phenotypes that were not observed following p110β inhibition, showing that, as in S phase (Marqués et al., 2009), an important mitotic function of p110β is kinase-independent.

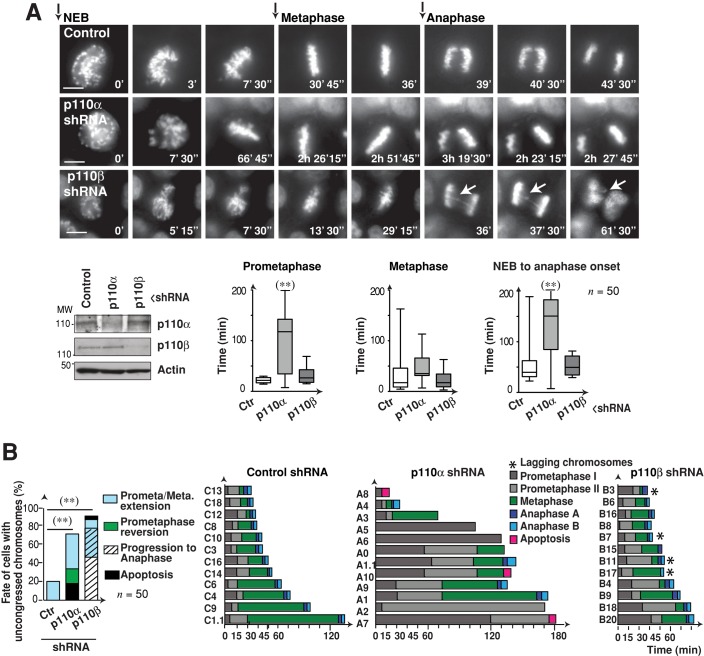

To confirm the mitotic defects induced by p110α or p110β depletion, we used time-lapse fluorescence microscopy in HeLa cells expressing histone 2B-GFP (H2B-GFP; Silljé et al., 2006), which permitted real-time evaluation of mitosis. We analyzed reduction of p110 expression by shRNA in Western blotting and examined mitosis by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy. We began analysis at the time of nuclear envelope breakdown (NEB; t = 0; Figure 6A, representative frames). Video microscopy confirmed the spindle rotation defects in p110α knocked-down cells (Figure 6A and Supplemental Movie S1). Quantification of the time spent by cells in prometaphase, metaphase, or from NEB to anaphase onset showed that ∼80% of control cells underwent rapid chromosome congression and separation. Mitosis was prolonged in the remaining 20% of cells, as previously reported (Kanda et al., 1998; Meraldi et al., 2004). Prolonged mitosis is due to cells with misaligned chromosomes that maintain an active SAC until all chromosomes are correctly located in the metaphase plate (Figure 6, A and B, and Movie S1).

FIGURE 6:

Premature anaphase in p110β-depleted cells. (A) HeLa cells expressing GFP-H2B were transfected with p110α or p110β shRNA (48 h) and visualized by video microscopy. Representative images at indicated times after NEB. Western blotting illustrates shRNA efficacy. Graphs show time: from NEB to metaphase onset, in metaphase (from metaphase onset until anaphase), and from NEB to anaphase. Scale bar: 5 μm. Student's t test: **, p < 0.01. (B) HeLa cells were treated and visualized as in (A). Left, graph shows the fate of the cells with uncongressed chromosomes in metaphase as determined by video microscopy. Right, graphs show the time frame from NEB to the indicated mitotic stages for 12 representative cells (n = 50). Prometaphase indicates the time from NEB until metaphase onset. Chi-square test: **, p < 0.01.

p110α knocked-down cells (∼70%) showed extended prometaphase (from NEB until metaphase); late metaphase plate organization; and after long prometaphase and metaphase, reversion to prophase or apoptosis in a fraction of the cells (Figure 6, A and B, and Movies S1 and S2). In contrast, ∼90% of the p110β knocked-down cells divided rapidly; showed congression defects; and although some showed extended prometaphase, most proceeded to anaphase with a wide metaphase plate and 25% had lagging chromosomes (Figure 6, A and B, and Movies S1 and S2). These results confirm the role of p110α in early mitosis and show defective chromosome segregation in p110β-silenced cells.

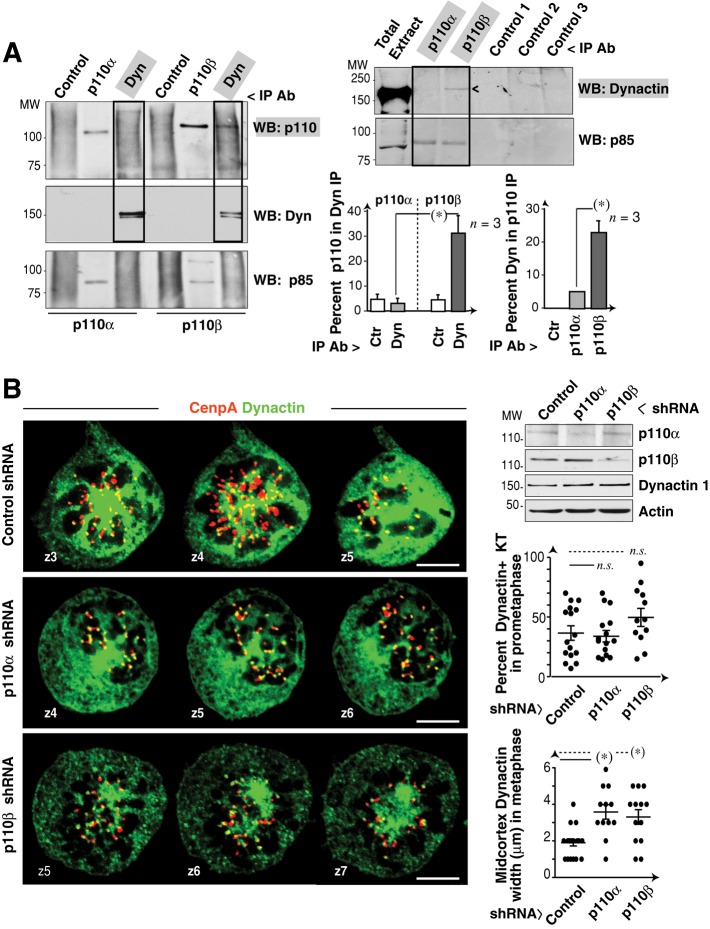

p110β associates with dynactin

Given that p110β regulates chromosome congression in a kinase-independent manner, p110β might exhibit a scaffolding function and associate a cell component that regulates chromosome congression, such as KT dynein/dynactin (King et al., 2000; Yang et al., 2007). To examine the potential interaction of p110β and dynein/dynactin, we immunopurified dynactin‑1 and tested for associated p110α or p110β in Western blotting. Cells were Colcemid-treated prior to analysis to increase KT-bound dynein/dynactin. Dynactin-1 associated with p110β, but not with p110α; the reverse analysis (p110 IP and anti–dynactin-1 Ab Western blotting) confirmed this association (Figure 7A).

FIGURE 7:

p110β associates with dynactin. (A) Extracts (1 mg) from C-metaphase–enriched (Colcemid-treated) U2OS cells were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti–dynactin-1 mAb; other samples (300 μg) were precipitated with anti-p110α or anti-p110β (positive control) or with an irrelevant Ab. p110α or p110β in complex with dynactin-1 was analyzed by Western blotting. Graph (left) shows the percentage of p110α and p110β signal in dynactin-1 immunoprecipitate relative to maximum signal. Mean ± SD (n = 3). Cell extracts were also precipitated with anti-p110α or anti-p110β, two irrelevant antibodies, or no Ab (controls 1–3); immunoprecipitates were resolved and dynactin-1 was determined by Western blotting. Anti-p85 Western blotting confirms equal protein loading. Graph (right) shows the percentage of dynactin signal in p110α or p110β IP compared with maximum signal. Mean ± SD (n = 3). (B) U2OS cells were transfected with p110α- or p110β-shRNA (48 h) and stained with anti–dynactin-1 and anti-CenpA antibodies. Representative serial z-sections (1 μm) of prometaphase cells are shown. Dynactin-1, p110α, and p110β levels were analyzed by Western blotting. Graphs show the percentage of dynactin-positive KT in prometaphase cells, relative to total KT (in all z‑sections) or the width (μm) of the dynactin cortex signal in metaphase. Scale bar: 5 μm. Student's t test: *, p < 0.05; n.s. = not significant.

p110β might regulate dynein/dynactin localization at the KT. To test this possibility, we reduced p110β expression in U2OS cells and analyzed dynactin localization at the KT by simultaneous staining of CenpA and dynactin-1. Because dynein/dynactin detaches from the KT following chromosome-MT attachment in metaphase (King et al., 2000), we analyzed prometaphase cells. Both p110α and p110β silencing increased the width of midcortex dynactin; however, control and p110α- and p110β-depleted cells showed comparable strong dynactin staining at KTs and a similar percentage of dynactin-1–positive KT (Figure 7B) showing that p110β does not regulate dynactin localization at the KT.

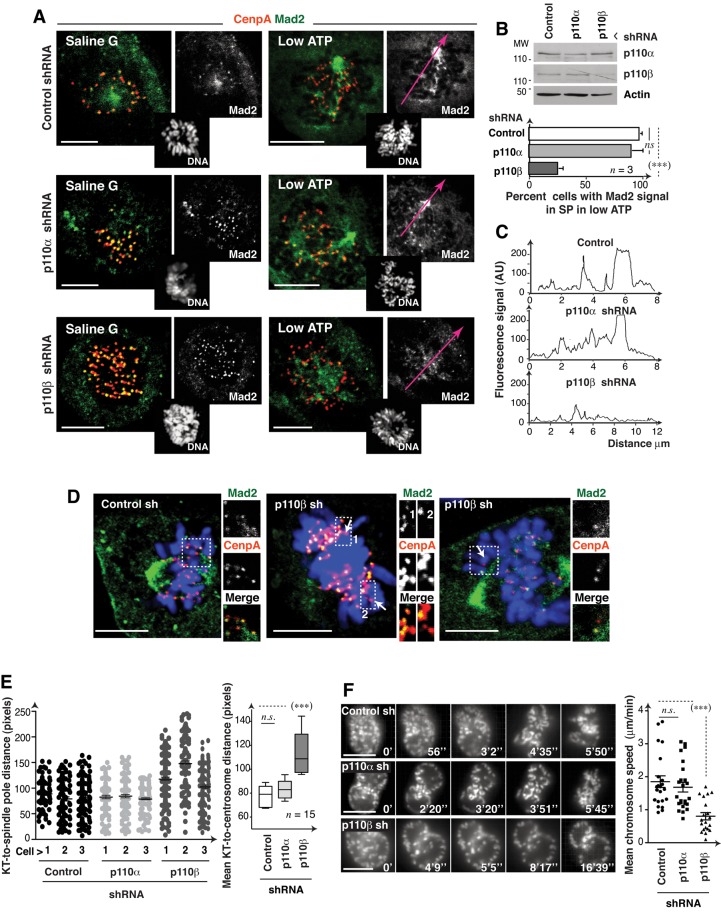

p110β regulates dynein/dynactin function at the KT

p110β might also control dynein/dynactin activity in the KT. Dynein/dynactin regulates SAC component transport from the KT to the spindle pole following MT-KT attachment. Low ATP levels permit poleward migration of dynein/dynactin cargo proteins, but not the reverse transport, inducing accumulation of SAC components at the spindle pole (Howell et al., 2001). To test the potential p110β function in the regulation of KT-dynein/dynactin activity, we measured transport of the SAC component Mad2 to the spindle pole.

ATP depletion caused Mad2 accumulation at spindle poles in controls and in p110α-depleted cells (Figure 8, A and B; Howell et al., 2001). In contrast, after p110β knockdown, Mad2 did not concentrate at spindle poles but persisted in a large percentage of KT, and the remainder diffused rapidly to cytoplasm (Figure 8, A–C). In the course of this analysis, we observed that approximately half of the KTs distant from the mitotic spindle (possibly unattached) were Mad2-negative in p110β-depleted metaphase cells (Figure 8D). p110β thus appears to control dynein/dynactin activity at the KT, as its depletion reduced Mad2 transport from the KT to the spindle pole. p110β nonetheless also appears to regulate stable Mad2 localization at the KT.

FIGURE 8:

p110β knockdown impairs Mad2 transport to spindle poles and prometaphase chromosome migration. (A) U2OS control or p110α or p110β knocked-down cells (48 h) were incubated in saline G or low-ATP medium (30 min) and stained with Hoechst 33258 (DNA), anti-Mad2 and anti-CenpA antibodies. Representative z-sections (1 μm) are shown. (B) Western blotting shows the reduction in p110α and p110β expression. Graph shows the percentage of cells with Mad2 concentrated at spindle poles in low ATP (mean ± SD; n = 3 assays; 15 cells/assay). (C) Fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units (AU, pixels) examined along the tracks (red) in (A). (D) Representative images of cells treated as in (A) and magnifications of mitotic spindle-distal KT, which lacked Mad2 signal (arrow) in p110β knocked-down cells. (E) Cells transfected as in (A) were stained with anti-dynactin and anti-CenpA antibodies. We measured the KT-to-centrosome distance for each KT. Left, graph shows the distance between each dynactin-positive KT and the centrosome in prometaphase cells (each dot represents a single KT; n = 3 cells of each type). We also calculated the mean KT-to-centrosome distance per cell and represented (right) the mean ± SD of these values for each cell type (n = 15 cells). (F) Individual frames from representative movies from control or p110α- or p110β-shRNA–transfected HeLa GFP-H2B cells (48 h). The graph shows chromosome speed in video microscopy. Scale bar: 5 μm. Student's t test: ***, p < 0.001; n.s. = not significant.

Dynein/dynactin activity also controls the rapid poleward movement of KT monoattached to the spindle pole in prometaphase (Yang et al., 2007). To confirm KT dynein/dynactin activity regulation by p110β, we measured the distance from dynactin-positive KT to the spindle poles in individual sections of prometaphase p110β knocked-down cells. p110β deletion led to a significant increase in mean KT-to-centrosome distance (Figure 8E). To further verify this defect, we used time-lapse video microscopy of H2B-GFP–expressing HeLa cells depleted of p110α or p110β. The mean velocity at which chromosomes moved away from the nuclear periphery (after NEB) was significantly slower in p110β knocked-down cells compared with control or p110α-depleted cells (Figure 8F and Movie S3), showing that p110β regulates prometaphase chromosome movement, an event controlled by KT dynein/dynactin.

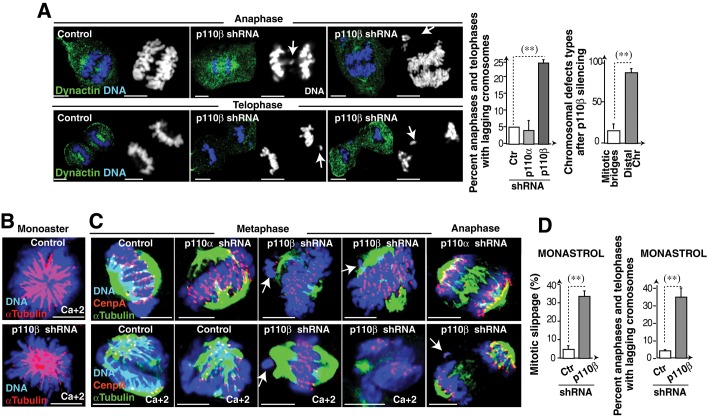

p110β depletion induces suboptimal SAC function

p110β-depleted cells showed lagging chromatids in metaphase (Figure 5). IF analysis and video microscopy showed that in anaphase/telophase, ∼25% of the p110β-deleted cells also had lagging chromatids (Figure 9A and Movies S1 and S2), suggesting suboptimal SAC function. Merotelic KT-MT attachment gives rise to chromosome bridges and segregation defects undetected by the SAC (Gregan et al., 2011); nonetheless, chromosome bridges were rare in p110β-depleted cells (Figure 9A). Chromosome defects in p110β-silenced cells are thus not due mainly to KT-MT merotelic attachments.

FIGURE 9:

p110β knockdown impairs SAC function. (A) Control or shRNA-transfected cells (48 h) were stained with anti-dynactin mAb and Hoechst 33258. Representative cells from p110β knocked-down cells. Arrows indicate lagging chromatids. Scale bar: 5 μm. Graphs show the percentage of anaphase and telophase cells with lagging chromatids (left) and of cells with mitotic bridges or chromosomes distal to the spindle (n = 50). (B) Representative images of control or p110β knocked-down U2OS cells (48 h) were treated with monastrol (4 h) and stained with anti–α-tubulin Ab and Hoechst 33258; cells were extracted in Ca2+-containing medium (indicated). (C) Control, p110α, or p110β knocked-down U2OS cells (48 h) were monastrol-treated (100 μM, 4 h) and released in medium (60 min). Representative confocal z-sections of IF performed with anti–α-tubulin, anti-CenpA, and Hoechst 33258. Some cells were extracted in Ca2+-containing medium (indicated); arrows indicate lagging chromosomes with no α-tubulin staining. (D) Control or shRNA-transfected cells (48 h) were incubated with monastrol (100 μM, 7 h) and analyzed by IF using α-tubulin Ab and Hoechst 33258 to determine the percentage of cells that escape SAC-induced prometaphase arrest (percent mitotic slippage, left graph). Other cells were incubated with monastrol (100 μM, 4 h) and released in fresh medium (60 min). Graph shows the percentage of anaphase and telophase cells with lagging chromatids (right). Scale bar: 5 μm. Student's t test: **, p < 0.01.

To determine whether KT-MT attachments were normal in p110β-depleted cells, we stained these cells with α-tubulin and CenpA. Detection of KT-MT attachments is difficult in U2OS cells compared with larger cells such as Xenopus oocytes (Kapoor et al., 2000), and we found no obvious differences in control and p110α- and p110β-depleted prometaphase cells (Figure S5A). We also examined KT-MT attachments after monastrol treatment (4 h). Monastrol inhibits centrosome separation, inducing synchronization of prometaphase cells with a monoaster spindle; mitotic progression after monastrol withdrawal thus requires MT rearrangement to convert KT-MT syntelic attachments to normal bipolar attachments (Kapoor et al., 2000). We examined α-tubulin and CenpA staining after monastrol treatment and deprivation. To improve visualization of MT at KT, we treated a fraction of the cells with calcium to destabilize non-KT microtubules (Kapoor et al., 2000). Most KTs of control or p110α knocked-down cells showed no obvious defects; in contrast, despite p110β-depleted cells arrested with monopolar spindles as controls, these cells presented lagging chromosomes that often lacked α-tubulin staining at the KT (∼75%; Figure 9, B and C), suggesting defective KT-MT attachment of unaligned chromosomes in these cells.

The presence of lagging chromosomes in anaphase prompted us to assess whether the SAC was fully functional in p110β-depleted cells. The SAC mediates cell retention in metaphase until all chromosomes attach to MT. We tested SAC function by examining retention in mitosis after MT depolymerization with Colcemid. When control cells were cultured with Colcemid (16 h) and subsequently in fresh medium (1–4 h), they proceeded to G1 (Figure S5B). In the continuous presence of Colcemid, however, they remained in C-metaphase; p110β and p110α knocked-down cells also remained in C-metaphase in Colcemid (Figure S5B), suggesting that p110β depletion does not impair SAC function after complete MT depolymerization.

Interference with the function of mitotic regulators, such as survivin, Aurora B, or Chk1, permits SAC function in Colcemid, but these cells show suboptimal SAC function with mitotic arrest by agents such as monastrol that have a less stringent action on MT dynamics (Lens et al., 2003; Zachos et al., 2007; Petsalaki et al., 2011). To study SAC function in monastrol-treated cells, we analyzed mitotic retention after prolonged monastrol treatment (7 h). Although most control cells remained in arrest with monoaster spindles, more than one-third of the p110β-depleted cells progressed to anaphase (Figure 9D). After monastrol treatment and release, one-third of anaphase and telophase p110β knocked-down cells had chromosomal errors (Figure 9D), supporting the possibility that SAC function is regulated by p110β.

Monastrol activates the SAC in HeLa cells, inducing accumulation of cells with monoaster spindles followed by induction of an apoptotic process. Mad2-depleted cells do not activate the SAC, are not arrested by monastrol, and undergo rapid mitosis without cell division, returning to G1; these cells remain in G1 and die only after prolonged treatment (48 h; Chin and Herbst, 2006). To test whether p110β depletion induces SAC defects similar to those of Mad2 silencing in monastrol, we examined the early apoptotic response and mitotic timing of p110β-depleted U2OS cells after prolonged monastrol treatment. Video microscopy of control and Mad2-depleted cells in monastrol confirmed previous observations; whereas control cells were arrested at short time periods and the majority underwent apoptosis after 20 h, Mad2-depleted cells did not arrest and showed accelerated mitosis and return to G1, with little apoptosis at 20 h (Figures 9B and S5C). p110β knocked-down cells had an intermediate phenotype. They arrested at early time points as control cells (Figure 9B), but did not undergo the SAC-mediated apoptosis observed in controls (Figure S5C). In contrast with controls, a significant proportion of p110β knocked-down cells escaped to mitosis (Figures 9D and S5C). p110β knockdown moderately reduced mitotic time compared with control cells (the very few that escaped arrest); combined depletion of Mad2 and p110β was similar to that of Mad2 (Figure S5C). p110β depletion thus induces suboptimal SAC function.

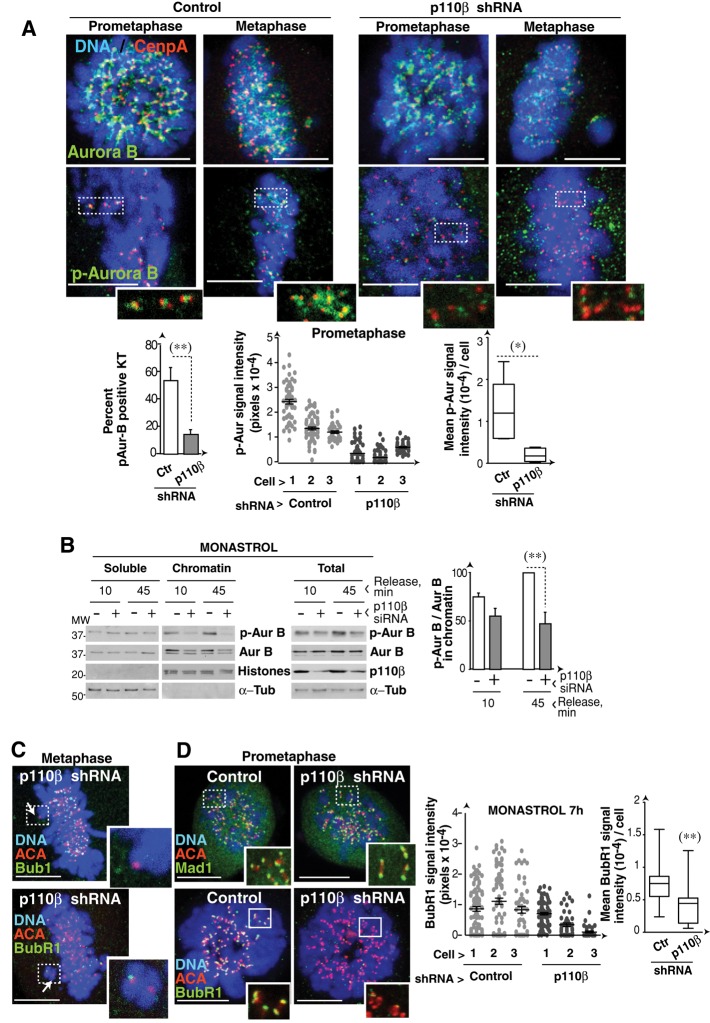

p110β regulates Aurora B localization and activation in KT

Aurora B and Ndc80 regulate KT-MT attachments and SAC activity (Karess, 2005). Because we detected defective KT-MT linkages in cells recovering from monastrol treatment (Figure 9C), we hypothesized that p110β might control Ndc80 or Aurora B. The Ndc80 complex blocks normal end-on KT-MT attachments, resulting in persistent, rapid, poleward chromosome movement in prometaphase (Vorozhko et al., 2008); we did not find this phenotype in p110β knocked-down cells (Figure 8). In contrast, whereas overexpression of inactive Aurora B induces severe defects in KT-spindle attachments, moderate expression of inactive Aurora B induces a milder phenotype that includes chromosome congression defects and premature anaphase. These cells retain an active SAC in Colcemid, but escape to mitosis in monastrol (Murata-Hori and Wang, 2002; Murata-Hori et al., 2002; Hauf et al., 2003), defects resembling those observed in p110β-depleted cells.

Aurora B regulates repair of KT-MT misattachments, which are frequent after monastrol treatment (Kapoor et al., 2000; Gregan et al., 2011). To study Aurora B activity after p110β silencing, we examined monastrol-treated (4 h) and monastrol-deprived (60 min) cells. IF analysis of Aurora B in prometaphase and metaphase showed a moderate signal decrease in p110β knocked-down cells compared with controls. Nonetheless, phospho‑Aurora B (p-Aurora B) signal intensity was significantly reduced in the KT of p110β-depleted cells compared with controls (Figures 10A and S6A). Aurora B prevents binding of chromosome passenger proteins (including Aurora B) to the early anaphase central spindle (Nakajima et al., 2011). In agreement with the lower p-Aurora B signal in KT, p110β knocked-down anaphase cells showed more rapid exit of Aurora B to the central spindle; telophase staining was nonetheless normal (Figure S6A). Staining of MT and p-Aurora B also illustrated the lower p-Aurora B signal in chromatids of p110β-silenced cells (Figure S6B).

FIGURE 10:

p110β knockdown reduces p-Aurora B activity in kinetochores. (A) Control, p110α, or p110β knocked-down U2OS cells (48 h) were monastrol-treated (100 μM, 4 h) and released in medium (60 min). Representative confocal z-sections of IF performed with the indicated antibodies and Hoechst 33258. Graphs show the percentage of p-Aurora B–positive KT in prometaphase. (B) U2OS cells were transfected with control or p110β siRNA, synchronized with monastrol (100 μM, 4 h), and collected after monastrol deprivation at 10 or 45 min. Total cell extracts and soluble and chromatin fractions were tested by Western blotting. Graphs show the p-Aurora B/Aurora B ratio in the chromatin fraction (left). (C) p110β knocked-down U2OS cells (48 h) were monastrol-treated (4 h) and then released (1 h); cells were stained with the indicated Ab. Representative confocal sections of metaphase cells with unaligned chromatids (indicated with an arrow). (D) U2OS cells were transfected as in (A) and maintained in monastrol for 7 h. Representative confocal z-stacks of IF performed with indicated antibodies and Hoechst 33258. We measured the fluorescence intensity of BubR1 signal in arbitrary units (AU, pixels) for each KT (each dot represents a single KT; n = 3 cells of each type). We also calculated the mean fluorescence intensity per cell and represented (right) the mean ± SD of these values for each cell type (n = 15 cells). Scale bar: 5 μm. Student's t test: **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05 (A and D, Student's test with Welch´s correction).

We confirmed suboptimal activation of Aurora B in p110β-silenced cells by analyzing p‑Aurora B levels in total cell extracts and in chromatin fractions of monastrol-treated cells. Control and p110β-depleted cells were arrested with monastrol and released for 10 and 45 min in medium, yielding a culture enriched in monopolar prometaphase cells (at 0 min) or including later mitotic phases (at 45 min; Figure S7B). Levels of Aurora B, and more markedly of p-Aurora B, were reduced in the chromatin fraction of p110β-depleted cells (Figure 10B). Even in total extracts, in which Aurora B levels were similar in control and p110β knocked-down cells, p-Aurora B levels were lower after p110β silencing (Figure 10B).

Defective Aurora B activation in KTs of p110β-depleted cells explains their premature anaphase entry, as chromosome passenger proteins prolong the binding of the SAC components Mad2 and BubR1 to KT (Ditchfield et al., 2003; Lens et al., 2003). As in the case of Mad2 (Figure 8D), BubR1 levels, and less markedly Bub1 levels, were reduced in spindle-distal KT of p110β-depleted cells (Figure 10C). Moreover, whereas Mad1 signal in KT of control and p110β knocked-down cells was similar, BubR1 KT localization, which is regulated by Aurora B (Lens et al., 2003; van der Waal et al., 2012), was reduced in p110β-depleted cells (Figures 10C and S7C). Bub1 is indirectly regulated by Aurora B (van der Waal et al., 2012) and was moderately reduced in p110β knocked-down cells (Figure S7C). Therefore, p110β controls both dynein/dynactin and Aurora B activity at KT, regulating chromosome congression and division, as well as optimal SAC function.

DISCUSSION

We analyzed the function of the ubiquitous PI3K isoforms p110α and p110β in mitosis. Our findings suggest that both isoforms are necessary for mitosis; whereas p110α controls midcortex PIP3 and mitotic spindle position, p110β regulates chromosome segregation and optimal function of the spindle checkpoint.

p110α regulates progression through prometaphase

Although PI3K function has been described in the control of Cdk1 activation, mitotic entry, and midcortex PIP3 (Shtivelman et al., 2002; Dangi et al., 2003; Toyoshima et al., 2007), the isoform that regulates these processes was unknown. We show that p110α is the isoform activated at M-phase entry following β1‑integrin activation. p110α inhibition reduced mitotic entry by > 50% (Figure 3), even though we did not use the maximal selective dose of the p110α inhibitor, as it causes apoptosis (unpublished data). The central role of p110α in early mitosis was confirmed by video microscopy, since p110α knocked-down cells showed prolonged prometaphase; the persistent rotation of the metaphase plate after p110α inhibition could hinder mitotic progression. The SAC generates a delay in cell cycle progression, allowing time for repair of KT-MT linkage defects; when these defects are not efficiently corrected, the cell is targeted for apoptosis (Yu, 2002). Indeed, a fraction of p110α knocked-down cells underwent apoptosis after long prometaphases. Nonetheless, p110α-deficient cells did not proceed to anaphase with lagging chromosomes, as did p110β-silenced cells. Inhibition or knockdown of p110α reduced and dispersed midcortex PIP3, regulating mitotic spindle position. Both p110α and p110β localized at the cell membrane (Figure S2); although p110β inhibition did not significantly affect midcortex PIP3 levels or spindle rotation, it regulated PIP3 membrane localization. It is possible that the β1‑integrin–p110α axis controls spindle position by additional mechanisms. p110α is thus the main isoform activated at M-phase entry and controls progression through prometaphase, midcortex PIP3, and spindle position.

p110β controls dynein/dynactin activity in kinetochores

p110β was activated near metaphase. Its deletion, but not its inhibition, caused defects in chromosome congression, motion, and segregation suggesting that p110β exhibits kinase-independent scaffolding functions as described in S-phase (Marqués et al., 2009). The dynein/dynactin complex is a critical regulator of mitosis. In KT, dynein/dynactin controls initial KT‑MT contacts, chromosome congression, and poleward movement in early prometaphase (O'Connell and Wang, 2000; Yang et al., 2007; Vorozhko et al., 2008). We show that p110β localized near chromosomes and associated with dynactin. Although p110β deletion did not reduce dynactin localization at KT, it impaired chromosome alignment and movement in prometaphase, as well as the dynein/dynactin-mediated transport of KT components in low-ATP medium. p110β deletion also induced multipolar spindles, a phenotype caused by dynein/dynactin defects (Quintyne et al., 2005). Chromosome motion is also controlled by the Ndc80 complex; nonetheless, whereas dynein/dynactin inhibition impairs chromosome poleward movement in prometaphase, Ndc80 regulates metaphase chromosome alignment and anaphase A (Yang et al., 2007; Vorozhko et al., 2008). These observations suggest that p110β controls chromosome alignment and movement in prometaphase by regulating dynein/dynactin activity in KT.

p110β regulates chromosome segregation

p110β deletion induced defective chromosome segregation. p110β-depleted cells showed lagging chromatids in ∼25% of metaphase cells that nonetheless underwent rapid metaphase–anaphase transition, and also showed these defects in anaphase and telophase (Figures 5B and 9A). The effect of p110β on chromosome segregation might be even greater, as these results were obtained after partial p110β depletion, since more stringent silencing reduces cell survival. The presence of lagging chromatids in late mitosis implies premature inactivation of the SAC. These defects cannot be explained by a defect in dynein/dynactin, which does not regulate SAC function (Yang et al., 2007). The SAC prevents premature mitosis in cells with unaligned chromosomes and remains active until all KTs are attached to MTs (Rieder et al., 1995; Chan and Yen 2003; Tanaka, 2008; Musacchio 2011). Aurora B and Ndc80 complexes regulate KT-MT linkages and control the SAC (Ruchaud et al., 2007). The observation that lagging chromatids in p110β-silenced cells are unattached from MT (Figure 9B) led us to propose that p110β might control the SAC by regulating Aurora B or Ndc80. Whereas interference with Ndc80 function overcomes SAC-induced metaphase arrest after MT depolymerization, cells expressing inactive Aurora B, such as p110β-depleted cells, retain an active SAC after MT depolymerization (Murata-Hori et al., 2002; McCleland et al., 2003; Petsalaki et al., 2011). The similar phenotypes observed following interference with Aurora B activity and p110β deletion prompted us to test whether p110β regulates Aurora B.

p110β controls Aurora B activity in KTs and in turn, SAC function

Aurora B forms part of the chromosome passenger protein complex (CPC) composed of Aurora B, survivin, borealin, and inner centromere protein (INCENP; Ruchaud et al., 2007). Aurora B detects errors in MT-KT attachments and regulates their repair (Lampson et al., 2004; Cimini 2007; Vader et al., 2008; Gregan et al., 2011). CPC also prolongs binding of SAC components to KT, thereby maintaining an active SAC until KT-MT linkages are repaired (Ditchfield et al., 2003; Lens et al., 2003). Aurora B is not essential for maintenance of an active SAC in normal conditions but is needed after cell treatment with drugs that limit spindle dynamics, such as monastrol (Hauf et al., 2003).

We show that p110β silencing triggers defective Aurora B binding and activation in the KT (Figure 10). CPC binding to chromosomes begins in G2 and increases in prometaphase; INCENP and survivin, as well as KT-specific epigenetic events, regulate Aurora B recruitment to mitotic chromosomes (Ainsztein et al., 1998; Adams et al., 2000; Beardmore et al., 2004). Several mechanisms have been reported for the control of Aurora B activity in KT in mitosis. Aurora B activation requires binding to centromeres and is controlled by other KT components, such as TD-60 and INCENP (Kaitna et al., 2000; Mollinari et al., 2003), that concentrate at centromeres in prophase (Kallio et al., 2002). Tensionless KT-MT linkages also regulate phosphorylation of Aurora B substrates by regulating its proximity to phosphatases (Gregan et al., 2011). The mechanism by which p110β regulates KT Aurora B is unknown. One of the events that controls Aurora B activity is KT binding to MT (Rosasco-Nitcher et al., 2008). Dynein/dynactin stabilizes kinetochore MT (Yang et al., 2007); it is thus possible that a defect in dynein/dynactin-mediated KT binding to MT in turn affects Aurora B activation. The mechanism for activation of Aurora B in KT and in the midzone is distinct (Fuller et al., 2008; Rosasco-Nitcher et al., 2008), providing an explanation for the selective defect of p110β-silenced cells in Aurora B activity at KT. As Aurora B regulates the SAC, the defect in Aurora B activity could account for the premature anaphase in p110β-silenced cells. Indeed, p110β regulates Mad2, BubR1, and Bub1 (but not Mad1) KT localization, in a manner similar to Aurora B (Ditchfield et al., 2003; Maldonado and Kapoor, 2011; van der Waal et al., 2012). The SAC defects observed might thus be due to suboptimal SAC activation in low p-Aurora–containing KTs (Figure 10A), which are unable to maintain an active SAC when a single KT remains unattached, but sufficient for SAC action when all KTs are unattached from MT (in Colcemid).

Differences in congression defects induced by Aurora B and dynein/dynactin

Both Aurora B and dynein/dynactin regulate chromosome congression. Whereas impairment of dynein/dynactin function results in a congression defect similar to that induced by p110β depletion (Movie S3; Yang et al., 2007), overexpression of inactive Aurora B induces movement of unattached chromosomes to two clusters in the cell center (Murata-Hori and Wang, 2002). Because this phenotype is not observed after p110β silencing, p110β could control chromosome movement by regulation of KT dynein/dynactin activity.

A unifying hypothesis for defects in cells with low p110β expression

p110β mediates the loading of regulatory proteins into chromatin. p110β regulates PCNA and Nbs1 binding to the replication fork and to double-stranded breaks, respectively (Marqués et al., 2009, Kumar et al., 2010). p110β might have a similar scaffolding function in KT, since chromosome segregation was affected by p110β depletion but not by its inhibition. The binding of a KT component that controls Aurora B and/or dynein/dynactin activation might be affected by p110β depletion. Although we detected no obvious KT defects in p110β knocked-down cells, the KT is composed of more that 70 proteins, even in organisms such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Meraldi et al., 2006); we thus cannot rule out the possibility that p110β regulates KT composition.

In this paper, we show that p110α is activated and necessary at mitotic entry, and that it controls prometaphase progression, midcortex PIP3 accumulation, and spindle localization. p110β is activated near metaphase, localizes near chromosomes, associates with dynactin, and controls dynein/dynactin and Aurora B activity at kinetochores. Reduction in p110β levels thus affects chromosome congression and movement, inducing premature silencing of the SAC and chromosome segregation defects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents

Western blots were probed with the following antibodies: anti–phospho-PKB (Ser-473), anti-PKB, anti-p110α, anti-p110β (all from Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), anti-p85 (Upstate Biotechnologies, Lake Placid, NY), anti-p150Glued (dynactin-1; BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA), anti-histones (Millipore, Billerica, CA), anti–α-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), anti–α-tubulin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), anti-CenpA, anti–phospho-Aurora B and anti–Aurora B (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). For immunoprecipitation, we used anti-p110α, anti-p110β, anti-p150Glued, and anti-p85; for immunofluorescence assays, anti-α-tubulin, anti-PIP3 (Echelon Biosciences, Salt Lake City, UT), anti-CenpA (Kremer et al., 1988; Abcam), anti-p150Glued, anti-Mad2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-p110α, anti-p110β, anti-Myc (Cell Signaling), anti-centromere antigen (anti-ACA; Antibodies Incorporated, Davis, CA), anti-CenpA, anti–phospho-Thr323-Aurora B and anti–Aurora B. BubR1 Ab was from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO); Mad1 and Bub1 antibodies were kindly donated by E. Nigg (Biozentrum, University of Basel, Switzerland). Specific inhibitors PIK75 and TGX221 were synthesized and used as previously described (Marqués et al., 2008, 2009). The Lia1/2 mAb for blocking human β1-integrin receptors was kindly donated by F. Sánchez-Madrid (CNIC, Madrid, Spain; Arroyo et al., 1992).

cDNA and shRNA

The pSG5-myc-K802R-hp110β and pSG5-myc-K805R-hp110β constructs have been described (Marqués et al., 2008). The pEGFP-PH-Btk plasmid encoding the Bruton's tyrosine kinase PH domain was kindly donated by T. Balla (National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD). For IF assays, we transfected pSG5-p110βMyc and pSG5-p85βHA or pSG5-p110βMyc (Marqués et al., 2008). pCFP-N1 and pYFP-N1 vectors (BD Biosciences), as well as pDsRed2 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), were used as transfection controls; specific shRNA for p110 sequences were as previously described (Marqués et al., 2008, 2009). siRNA for human hp110β or scrambled siRNA were custom-made (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). shRNA for hMad2 was from Origene (Rockville, MD). For rescue experiments, NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with shRNA for murine p110β or p110β in combination with vectors of cDNAs encoding human p110α or p110β (pSG5-p110αMyc or pSG5-p110βMyc).

Cell culture, transfection and lysis, Western blotting, immunoprecipitation, and PI3K assays

NIH 3T3, HeLa, and U2OS cells were cultured as previously described (Álvarez et al., 2001). Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) and Jet Pei-NaCl (Qbiogene). Total cell extracts were prepared in RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Álvarez et al., 2001); Western blotting was performed as previously described (Marqués et al., 2008). To test p110/dynactin-1 association, we extracted cells in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM KCl buffer (15 min, on ice), after which NP-40 was added to a final concentration of 0.3% (10 min, on ice). For the reciprocal assay, dynactin-1 was immunoprecipitated from extracts obtained in a buffer containing 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM KCl, 0.5% NP-40, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors (30 min, on ice). Immunoprecipitation was performed by mixing lysates (4ºC, 3–4 h) with the appropriate antibody; this was followed by incubation with 40 μl of either protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany) preblocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA; 4ºC, 1 h) or protein G-Sepharose (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA).

For kinase assays, we used RIPA cell extracts. PI3K was immunoprecipitated using anti-p110α or anti-p110β antibodies. Immunopurified p110α or p110β was dissolved in 45 μl of 50 mM HEPES containing phosphoinositide-4,5-diphosphate (0.5 mg/ml; Sigma- Aldrich). For the kinase reaction (final volume 50 μl), we used 5 μl 10X kinase buffer (10 μCi [32P]ATP, 100 mM MgCl2, and 200 μM unlabeled ATP). Reactions were incubated (25 min, 37ºC) and terminated by addition of 1 mM HCl (100 μl) and methanol/chloroform (1:1 vol/vol; 200 μl). Phospholipids were resolved in silica gel plates as previously described (Marqués et al., 2008).

For subcellular fractionation, we used a previously described protocol (Riva et al., 2004). Cells were lysed in a hypotonic buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 0.2 mM Na3VO4, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors (5 min, on ice). Lysates were centrifuged (1500 × g, 4ºC); the supernatant was the soluble fraction. Pellets were resuspended in washing buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF, and protease inhibitors, centrifuged (1500 × g, 4ºC), and extracted in nuclear buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM PMSF, 0.5 μM okadaic acid, and protease inhibitors) containing DNase I (100–200 U/107 cells; 30 min, 37°C; Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were centrifuged (13,000 × g, 5 min, 4°C), and pellets were resuspended in a high-salt buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) and 2 M NaCl (30 min, 4ºC) and centrifuged (13,000 × g, 5 min, 4°C). Supernatants were the chromatin fraction.

Cell cycle, flow cytometry, and video microscopy

Cell cycle distribution was examined by DNA staining using propidium iodide and analyzed by flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) using Multicycle AV (Phoenix Flow Systems, San Diego, CA). We used anti-pH3 (Ser-10)-Alexa Fluor 488 (Cell Lab) to distinguish M and G2 cell cycle phases by flow cytometry. Cell cultures were synchronized in S phase by aphidicolin block (Álvarez et al., 2001). For metaphase arrest, we used mild Colcemid treatment (75 ng/ml, 12 h, yielding ∼60% cells with 4n DNA; Álvarez et al., 2001) or 100 ng/ml, 14 h (>90% cells with 4n DNA). HeLa cells expressing H2B-GFP were a kind gift of E. Nigg (Biozentrum, University of Basel, Switzerland; Silljé et al., 2006). HeLa cells were filmed on an Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) CellR microscope (63×/1.45 numerical aperture [NA] objective). Images were captured every 45 s for 2.5 h. For studying chromosome prometaphase movement, HeLa cells were captured every 4 s 361 ms for 10 min on a Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) DM16000B (63×/1.3 NA objective). Videos were processed with Imaris (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland) version 7.3.2 and ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). To measure mitotic time in p110β- and/or Mad2-depleted U2OS cells, we identified cells by simultaneous transfection with pDsRed2 and used the Leica DM16000B (20×/0.4 NA objective); images were acquired every 15 min for 20 h. Mitotic time was measured from the time of cell rounding until anaphase onset; for Mad2-depleted cells, mitotic time was from cell rounding with condensed chromatin until cell spreading and chromatin decondensation.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

For immunofluorescence, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and permeabilized in 1% BSA and 0.3% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (5 min or 7 min for cytosol extraction). Cells were blocked with 1% BSA, 10% goat serum, and 0.01% Triton X-100 (30 min), and then incubated with appropriate primary antibodies (1 h, room temperature). We used Cy3 and Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated to goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG), and Cy3-goat anti-human IgG as secondary Ab (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). DNA was stained with Hoechst 33258 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Cells were visualized using a 60×/1.4 Plan-Apo objective on an inverted Olympus Fluoview 1000 microscope or a 63×/1.4 objective on an inverted Leica SP5 microscope. Destabilization of non-KT MT in monastrol-treated U2OS cells was as described for PtK2 cells (Kapoor et al., 2000). U2OS cells were incubated with monastrol (100 mM, 4 h); permeabilized in a 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100 PBS buffer (90 s); fixed in 4% formaldehyde; and immunostained. The ATP reduction assay was performed as described for PtK2 cells (Howell et al., 2001); cells were washed in saline (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.6 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.3) and incubated with saline-G (saline with 4.5 g/l d-glucose) or saline with 5 mM sodium azide, 1 mM 2-deoxyglucose and 0.3 U/ml oxyrase (30 min, 37°C; low ATP conditions, Figure 8A).

Quantitation, data analysis, and statistical analyses

The distance from dynactin-positive KT to the spindle poles in prometaphase cells was measured using ImageJ software. The velocity of chromosome movement after NEB (in prometaphase) was calculated as the length of the trajectory, divided by the time needed for this movement. For each cell we calculated the mean velocity of six representative chromosomes. Gel bands and fluorescence intensity were quantitated with ImageJ.

Statistics and quantitation

Student's t -test and chi-square test were used; statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Significance was defined as p < 0.05. Gel bands and fluorescence intensity were quantitated with ImageJ. All quantitation was performed using low-exposure film (in the linear range); for quantitation of IF images, all images were acquired in the same conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Nigg (Biozentrum, University of Basel, Switzerland) for GFP-H2B-expressing HeLa cells and antibodies, F. Sánchez-Madrid (CNIC, Madrid, Spain) for Lia1/2 antibody, T. Balla (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for Btk‑PH, A. I. Checa for help with confocal microscopy, and C. Mark for editorial assistance. V.S. was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. This work was financed by grants from the Spanish Association Against Cancer, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (SAF 2007-63624, SAF2010-21019), and the Network of Cooperative Research (RD07/0020/2020) of the Carlos III Institute, the Madrid regional government, and the Sandra Ibarra Foundation.

Abbreviations used:

- Ab

antibody

- anti-ACA

anti-centromere antigen

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- C-metaphase

Colcemid-blocked metaphase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- H2B-GFP

histone 2B-GFP

- IF

immunofluorescence

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- INCENP

inner centromere protein

- KT

kinetochore

- Mad1/Mad2

mitotic arrest–deficient proteins 1 and 2

- MT

microtubules

- NA

numerical aperture

- NEB

nuclear envelope breakdown

- p-Aurora B

phospho‑Aurora B

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PH

pleckstrin homology

- pH3

phosphohistone H3

- PI3K

phosphoinositide-3-kinase

- PIP3

phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate

- PKB

protein kinase B

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- SAC

spindle assembly checkpoint

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E12-05-0371) on October 10, 2012.

REFERENCES

- Adams RR, Wheatley SP, Gouldsworthy AM, Kandels-Lewis SE, Carmena M, Smythe C, Gerloff DL, Earnshaw WC. INCENP binds the Aurora-related kinase AIRK2 and is required to target it to chromosomes, the central spindle and cleavage furrow. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1075–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00673-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsztein AM, Kandels-Lewis SE, Mackay AM, Earnshaw WC. INCENP centromere and spindle targeting: identification of essential conserved motifs and involvement of heterochromatin protein HP1. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1763–1774. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez B, Martínez-A C, Burgering B, Carrera AC. Forkhead transcription factors contribute to the execution of the mitotic program in mammals. Nature. 2001;413:744–747. doi: 10.1038/35099574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo AG, Sánchez-Mateos P, Campanero MR, Martín-Padura I, Dejana E, Sánchez-Madrid F. Regulation of VLA integrin-ligand interactions through the β1 subunit. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:659–670. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.3.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardmore VA, Ahonen LJ, Gorbsky GJ, Kallio MJ. Survivin dynamics increases at centromeres during G2/M phase transition and is regulated by microtubule-attachment and Aurora B kinase activity. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4033–4042. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busson S, Dujardin D, Moreau A, Dompierre J, De Mey JR. Dynein and dynactin are localized to astral microtubules and at cortical sites in mitotic epithelial cells. Curr Biol. 1998;8:541–544. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan GK, Yen TJ. The mitotic checkpoint: a signaling pathway that allows a single unattached kinetochore to inhibit mitotic exit. Prog Cell Cycle Res. 2003;5:431–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin GM, Herbst R. Induction of apoptosis by monastrol, an inhibitor of the mitotic kinesin Eg5, is independent of the spindle checkpoint. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2580–2591. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimini D. Detection and correction of merotelic kinetochore orientation by Aurora B and its partners. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1558–1564. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.13.4452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukier IH, Li Y, Lee JM. Cyclin B1/Cdk1 binds and phosphorylates Filamin A and regulates its ability to cross-link actin. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1661–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangi S, Cha H, Shapiro P. Requirement for PI3K activity during progression through S-phase and entry into mitosis. Cell Signal. 2003;15:667–675. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(03)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditchfield C, Johnson VL, Tighe A, Ellston RC, Johnson T, Mortlock A, Keen N, Taylor SS. Aurora B couples chromosome alignment with anaphase by targeting BubR1, Mad2 and CENP-E to kinetochores. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:267–280. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruman DA, Cantley LC. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase in immunological systems. Semin Immunol. 2002;14:7–18. doi: 10.1006/smim.2001.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller BG, Lampson MA, Foley EA, Rosasco-Nitcher S, Le KV, Tobelmann P, Brautigan DL, Stukenberg PT, Kapoor TM. Midzone activation of Aurora B in anaphase produces an intracellular phosphorylation gradient. Nature. 2008;453:1132–1136. doi: 10.1038/nature06923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Z, Kumar A, Marqués M, Cortés I, Carrera AC. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase controls early and late events in mammalian cell division. EMBO J. 2006;25:655–661. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregan J, Polakova S, Zhang L, Tolic-Nørrelykke IM, Cimini D. Merotelic kinetochore attachment: causes and effects. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauf S, Cole RW, LaTerra S, Zimmer C, Schnapp G, Walter R, Heckel A, van Meel J, Rieder CL, Peters JM. The small molecule Hesperadin reveals a role for Aurora B in correcting KT-MT attachment and in maintaining the spindle assembly checkpoint. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:281–294. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell BJ, McEwen BF, Canman JC, Hoffman DB, Farrar EM, Rieder CL, Salmon E. Cytoplasmic dynein/dynactin drives kinetochore protein transport to the spindle poles and has a role in mitotic spindle checkpoint inactivation. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:1159–1172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SM, Kazlauskas A. Growth-factor-dependent mitogenesis requires two distinct phases of signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:165–172. doi: 10.1038/35055073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaitna S, Mendoza M, Jantsch-Plunger V, Glotzer M. Incenp and an Aurora-like kinase form a complex essential for chromosome segregation and efficient completion of cytokinesis. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1172–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00721-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallio MJ, McCleland ML, Stukenberg PT, Gorbsky GJ. Inhibition of Aurora B kinase blocks chromosome segregation, overrides the spindle checkpoint, and perturbs microtubule dynamics in mitosis. Curr Biol. 2002;12:900–905. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00887-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda T, Sullivan KF, Wahl GM. Histone-GFP fusion protein enables sensitive analysis of chromosome dynamics in living mammalian cells. Curr Biol. 1998;8:377–385. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor TM, Mayer TU, Coughlin ML, Mitchison TJ. Probing spindle assembly mechanisms with monastrol, a small molecule inhibitor of the mitotic kinesin, Eg5. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:975–988. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karess R. Rod-Zw10-Zwilch: a key player in spindle checkpoint. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JM, Hays TS, Nicklas B. Dynein is a transient kinetochore component whose binding is regulated by microtubule attachment, not tension. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:739–748. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.4.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer L, del Mazo J, Avila J. Identification of centromere proteins in different mammalian cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1988;46:196–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Fernadez-Capetillo O, Carrera AC. Nuclear phosphoinositide 3-kinase β controls double-strand break DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7491–7496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914242107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampson MA, Renduchitala K, Khodjakov A, Kapoor TM. Correcting improper chromosome-spindle attachments during cell division. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:232–237. doi: 10.1038/ncb1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lens SMA, Wolthuis RMF, Klompmaker R, Kauw J, Agami R, Brummelkamp T, Kops G, Medema RH. Survivin is required for a sustained spindle checkpoint arrest in response to lack of tension. EMBO J. 2003;22:2934–2947. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Cheng H, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:627–644. doi: 10.1038/nrd2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado M, Kapoor TM. Constitutive Mad1 targeting to kinetochores uncouples checkpoint signalling from chromosome biorientation. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:475–482. doi: 10.1038/ncb2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marqués M, Kumar A, Cortés I, Gonzalez-García A, Hernández C, Moreno-Ortiz MC, Carrera AC. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases p110α and p110β regulate cell cycle entry, exhibiting distinct activation kinetics in G1 phase. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2803–2814. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01786-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marqués M, Kumar A, Poveda AM, Zuluaga S, Hernández C, Jackson S, Pasero P, Carrera AC. Specific function of phosphoinositide 3-kinase beta in the control of DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7525–7530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleland ML, Gardner RD, Kallio MJ, Daum JR, Gorbsky GJ, Burke DJ, Stukenberg PT. The highly conserved Ndc80 complex is required for kinetochore assembly, chromosome congression, and spindle checkpoint activity. Genes Dev. 2003;17:101–114. doi: 10.1101/gad.1040903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meraldi P, Draviam VM, Sorger PK. Timing and checkpoints in the regulation of mitotic progression. Dev Cell. 2004;7:45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meraldi P, McAinsh AD, Rheinbay E, Peter K. Phylogenetic structural analysis of centromeric DNA and kinetochore proteins. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R23. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-3-r23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollinari C, et al. The mammalian passenger protein TD-60 is an RCC1 family member with an essential role in prometaphase to metaphase progression. Dev Cell. 2003;5:295–307. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata-Hori M, Tatsuka M, Wang YL. Probing the dynamics and functions of aurora B kinase in living cells during mitosis and cytokinesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1099–1108. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-09-0467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata-Hori M, Wang YL. The kinase activity of aurora B is required for kinetochore-microtubule interactions during mitosis. Curr Biol. 2002;12:894–899. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00848-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A. Spindle assembly checkpoint: the third decade. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366:3595–3604. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A, Salmon ED. The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:379–393. doi: 10.1038/nrm2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, Cormier A, Tyers RG, Pigula A, Peng Y, Drubin DG, Barnes G. Ipl1/Aurora-dependent phosphorylation of Sli15/INCENP regulates CPC-spindle interaction to ensure proper microtubule dynamics. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:137–153. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA. Cyclin-dependent protein kinases: key regulators of the eukaryotic cell cycle. Bioessays. 1995;17:471–480. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell CB, Wang Y. Mammalian spindle orientation and position respond to changes in cell shape in a dynein-dependent fashion. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:1765–1774. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.5.1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petsalaki E, Akoumianaki T, Black EJ, Gillespie DA, Zachos G. Phosphorylation at serine 331 is required for Aurora B activation. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:449–466. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201104023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintyne NJ, Reing JE, Hoffelder DR, Gollin SR, Saunders WS. Spindle multipolarity is prevented by centrosomal clustering. Science. 2005;307:127–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1104905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder CL, Cole RW, Khodjakov A, Sluder G. The checkpoint delaying anaphase in response to chromosome monoorientation is mediated by an inhibitory signal produced by unattached kinetochores. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:941–948. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.4.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva F, Savio M, Cazzalini O, Stivala LA, Scovassi IA, Cox LS, Ducommun B, Prosperi E. Distinct pools of proliferating cell nuclear antigen associated to DNA replication sites interact with the p125 subunit of DNA polymerase delta or DNA ligase I. Exp Cell Res. 2004;15:357–367. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosasco-Nitcher SE, Lan W, Khorasanizadeh S, Stukenberg PT. Centromeric Aurora-B activation requires TD-60 MT and substrate priming phosphorylation. Science. 2008;319:469–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1148980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchaud S, Carmena M, Earnshaw WC. Chromosomal passengers: conducting cell division. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:798–812. doi: 10.1038/nrm2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Scharenberg AM, Kinet JP. Interaction between the Btk PH domain and phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-P3 directly regulates Btk. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16201–16206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santaguida S, Vernieri C, Villa F, Ciliberto A, Musacchio A. Evidence that Aurora B is implicated in SAC signalling independently of error correction. EMBO J. 2011;30:1508–1519. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtivelman E, Sussman J, Stokoe D. A role for PI 3-kinase and PKB activity in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. Curr Biol. 2002;12:919–924. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00843-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silljé HH, Nagel S, Körner R, Nigg EA. HURP is a Ran-importin β-regulated protein that stabilizes kinetochore microtubules in the vicinity of chromosomes. Curr Biol. 2006;16:731–742. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka TU. Bi-orienting chromosomes: acrobatics on the mitotic spindle. Chromosoma. 2008;117:521–533. doi: 10.1007/s00412-008-0173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima F, Matsumura S, Morimoto H, Mitsushima M, Nishida E. PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 regulates spindle orientation in adherent cells. Dev Cell. 2007;13:796–811. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vader G, Maia AF, Lens SM. The chromosomal passenger complex and the spindle assembly checkpoint: kinetochore-microtubule error correction and beyond. Cell Div. 2008;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Waal MS, Hengeveld RC, van der Horst A, Lens SM. Cell division control by the Chromosomal Passenger Complex. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:1407–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorozhko VV, Emanuele MJ, Kallio MJ, Stukenberg PT, Gorbsky GJ. Multiple mechanisms of chromosome movement in vertebrate cells mediated through the Ndc80 complex and dynein/dynactin. Chromosoma. 2008;117:169–179. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0135-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Tulu US, Wadsworth P, Rieder CL. Kinetochore dynein is required for chromosome motion and congression independent of the spindle checkpoint. Curr Biol. 2007;17:973–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H. Regulation of APC-Cdc20 by the spindle checkpoint. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:706–714. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00382-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachos G, Black EJ, Walker M, Scott MT, Vagnarelli P, Earnshaw WC, Gillespie DA. Chk1 is required for spindle checkpoint function. Dev Cell. 2007;12:247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.