Abstract

Although the positive effect of elevated CO2 concentration [CO2] on plant growth is well known, it remains unclear whether global climate change will positively or negatively affect crop yields. In particular, relatively little is known about the role of hormone pathways in controlling the growth responses to elevated [CO2]. Here, we studied the impact of elevated [CO2] on plant biomass and metabolism in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) in relation to the availability of gibberellins (GAs). Inhibition of growth by the GA biosynthesis inhibitor paclobutrazol (PAC) at ambient [CO2] (350 µmol CO2 mol−1) was reverted by elevated [CO2] (750 µmol CO2 mol−1). Thus, we investigated the metabolic adjustment and modulation of gene expression in response to changes in growth of plants imposed by varying the GA regime in ambient and elevated [CO2]. In the presence of PAC (low-GA regime), the activities of enzymes involved in photosynthesis and inorganic nitrogen assimilation were markedly increased at elevated [CO2], whereas the activities of enzymes of organic acid metabolism were decreased. Under ambient [CO2], nitrate, amino acids, and protein accumulated upon PAC treatment; however, this was not the case when plants were grown at elevated [CO2]. These results suggest that only under ambient [CO2] is GA required for the integration of carbohydrate and nitrogen metabolism underlying optimal biomass determination. Our results have implications concerning the action of the Green Revolution genes in future environmental conditions.

The worldwide emission of gases derived from fossil fuel burning is seen as a major cause of global climate change mainly visible as an increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration [CO2] (Baker and Allen, 1994), which could rise to more than 750 µL L−1 by the end of this century (Meehl et al., 2007). Since a higher [CO2] increases photosynthesis, development, and in many cases yield, it has often been considered as a positive factor for future crop agriculture (Baker, 2004; Ainsworth, 2008). On the other hand, cereals grown under elevated [CO2] show a decreased harvest index (i.e. the ratio of grain yield to total biomass; Meehl et al., 2007) and decreased seed quality (Taub et al., 2008). Elevated [CO2] leads to a stimulation of leaf growth by triggering both cell expansion and cell division (Masle, 2000; Taylor et al., 2003; Luomala et al., 2005). Elongation growth is strongly influenced by GAs (Richards et al., 2001). During the Green Revolution, breeding programs focused on increasing the harvest index by selecting semidwarf cereal varieties that invest relatively few resources in vegetative growth but support increased partition to grains (Khush, 2001; Phillips, 2004). It was subsequently discovered that most Green Revolution varieties, selected for their semidwarf phenotype, harbored mutations affecting GA biosynthesis (Hedden, 2003). Such mutants include Semidwarf1 (SD1) in rice (Oryza sativa), which encodes a GA 20-oxidase (Spielmeyer et al., 2002), and the wheat (Triticum aestivum) Reduced-height1B and Reduced-height1D and maize (Zea mays) dwarf d8 genes, which encode orthologs of the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Gibberellin Insensitive gene (Peng et al., 1999). However, relatively little is known concerning the action of GA in determining plant growth at elevated [CO2]. For example, the yield of the miracle rice line IR8, the original sd1 mutant, has dropped by 15% compared with the levels achieved in the 1960s (Peng et al., 2010), in part due to global climate change, including increased temperature and [CO2], but also due to changed soil properties and increased biotic stress.

GA biosynthesis and signaling pathways have been studied intensively, particularly in Arabidopsis (Hedden and Phillips, 2000; Olszewski et al., 2002; Yamaguchi, 2008; Middleton et al., 2012). Early steps in GA biosynthesis involve the cyclization of geranylgeranyl diphosphate to ent-copalyl diphosphate, which in turn is converted to ent-kaurene. The enzymes that catalyze these reactions are ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase and ent-kaurene synthase, respectively (Sun and Kamiya, 1997). Subsequent reactions catalyzed by the cytochrome P450 enzymes ent-kaurene oxidase and ent-kaurenoic acid oxidase produce ent-kaurenoic acid and GA12 from ent-kaurene (Helliwell et al., 2001; Yamaguchi, 2008). In the final steps of the pathway, GA12 is converted to GA4 through oxidations on C-20 and C-3 by GA 20-oxidase (GA20ox) and GA 3-oxidase (GA3ox), respectively (Hedden and Phillips, 2000; Olszewski et al., 2002). The content of bioactive GA is negatively regulated by GA 2-oxidases (GA2ox; Martin et al., 1999), which at the transcriptional level are induced by elevated levels of GA (Thomas et al., 1999; Elliott et al., 2001). Furthermore, GA homeostasis is also achieved by transcriptional negative feedback regulation of GA20ox and GA3ox biosynthesis genes (Yamaguchi, 2008). In principle, the expression of GA biosynthetic genes correlates with the level of GA (Cowling et al., 1998; Ogawa et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2007; Yamaguchi, 2008). In addition to homeostatic mechanisms that control GA levels, the metabolism of GAs is particularly sensitive to developmental and environmental factors (Sun and Gubler, 2004; Fleet and Sun, 2005). The increase of atmospheric [CO2] during recent decades has promoted a growing interest in the function of this environmental factor on plant growth.

Previously, we investigated the modulation of gene regulation and metabolic acclimation during altered plant growth imposed by a change of the GA regime (Ribeiro et al., 2012). Comparison of gene expression and metabolite profiles demonstrated that low GA level uncouples growth from carbon and nitrogen availability, while under normal or high GA levels a tight relationship exists between carbon availability and growth. Since the atmospheric [CO2] is steadily increasing (Solomon et al., 2007) and the GA biosynthesis pathway has been the major driver for the spectacular increases in yield during the Green Revolution (Peng et al., 1999), we investigated how elevated [CO2] affects plant growth and metabolism of Arabidopsis grown under different GA regimes.

RESULTS

Elevated [CO2] Enhances the Growth of Plants with Low-GA Metabolism

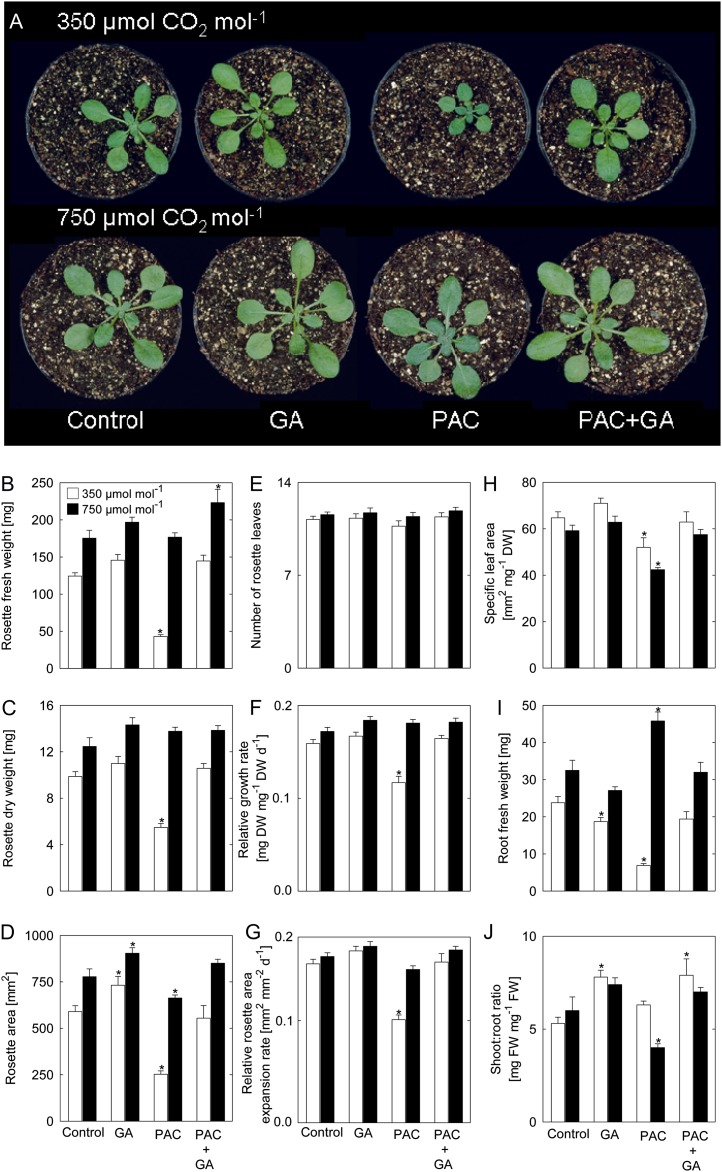

To obtain insights into the connection between carbon availability and GA, we examined the effect of elevated [CO2] (750 µmol CO2 mol−1) on altered GA regimes. Paclobutrazol (PAC) is a chemical inhibitor of the enzyme ent-kaurene oxidase, which performs the first committed step toward GA biosynthesis (Rademacher, 2000). The inhibitory effect of PAC on Arabidopsis plant growth in ambient [CO2] was reverted in plants grown at elevated [CO2] (Fig. 1A). Arabidopsis plants grown at ambient [CO2] in soil supplemented with PAC showed approximately 2- and 3-fold reductions of rosette fresh weight and dry weight, as well as rosette area, compared with controls, while at elevated [CO2] no growth repression was observed in the presence of PAC (Fig. 1, B–D). The number of rosette leaves was unaffected in all treatments performed (Fig. 1E). Under ambient [CO2], PAC treatment led to reductions of the relative growth rate and relative rosette area expansion rate, which were not observed when plants were grown at elevated [CO2] (Fig. 1, F and G). The application of GA under both ambient and elevated [CO2] had a significant positive effect on rosette area (Fig. 1D), while biomass only tended to be increased (Fig. 1, B–D). Thus, the addition of GA has the same effect under both [CO2] regimes, indicating that the growth-promoting response to GA is not saturated.

Figure 1.

Phenotypic changes of Arabidopsis plants caused by treatment with PAC and/or GA grown at ambient or elevated [CO2]. A, Phenotypes of 28-d-old plants grown at 350 or 750 µmol CO2 mol−1. Note the reversion to normal growth of PAC-treated plants at elevated [CO2]. B, Rosette fresh weight. C, Rosette dry weight. D, Rosette area. E, Number of rosette leaves. F, Relative growth rate. G, Relative rosette area expansion rate. H, Specific leaf area. I, Root fresh weight. J, Shoot-to-root ratio. Asterisks indicate values determined by Student’s t test to be significantly different from control plants at the shown [CO2] (P < 0.05). Values are means ± se of four independent experiments. DW, Dry weight; FW, fresh weight.

Whereas under ambient [CO2], the rosette biomass (fresh weight and dry weight) and rosette area strongly increased when GA was added to plants treated with PAC (Fig. 1, B–D), there was only a slight growth stimulation of PAC-treated plants by GA at high [CO2]. Moreover, at ambient [CO2], the relative growth rate and relative rosette area expansion rate of PAC-treated plants were markedly increased by GA application, but no difference was observed for these parameters under elevated [CO2] (Fig. 1, F and G). Still, specific leaf area was affected by PAC under both [CO2] regimes and was restored by external application of GA (Fig. 1H). Of note, PAC treatment affected root growth negatively under ambient [CO2] but positively at elevated [CO2], resulting in a different shoot-root ratio (Fig. 1, I and J). This observation might in part be related to the stimulation of root growth by elevated [CO2] (Niu et al., 2011). Taken together, the inhibitory effect of PAC on the growth of Arabidopsis at ambient [CO2] was overcome when plants were grown at high [CO2].

Leaf Starch, Soluble Carbohydrate, and Organic Acids

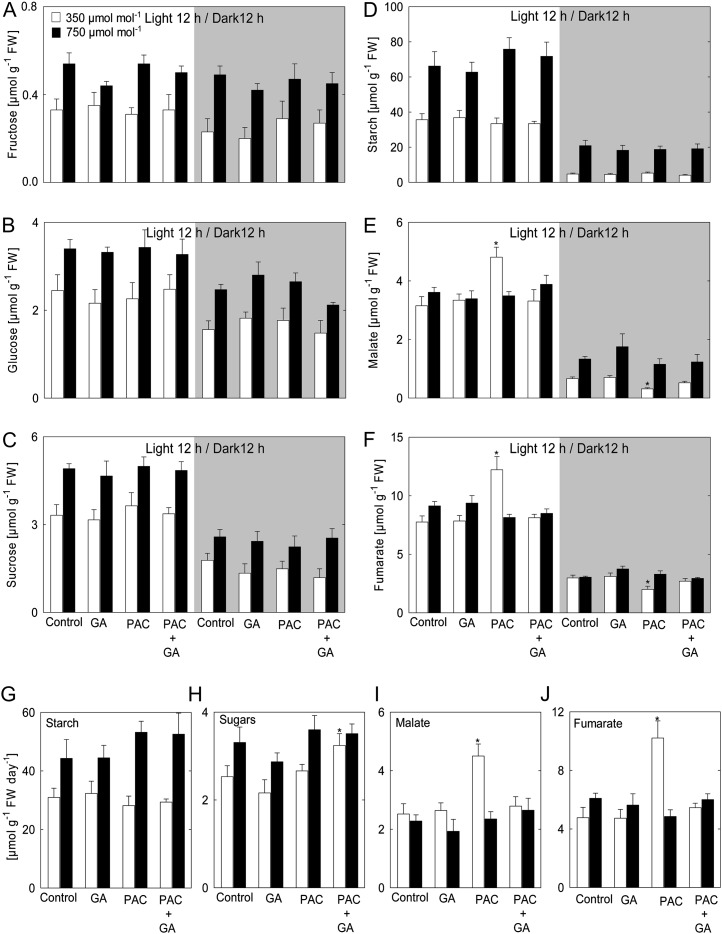

Growth of Arabidopsis at elevated [CO2] for 11 d resulted in an increase in Fru, Glc, Suc, and starch (Fig. 2, A–D) both at the end of the day and the end of the night in a manner independent of the GA regime. Treatment of plants with either GA or PAC plus GA did not alter the levels of malate and fumarate under ambient or elevated [CO2] in end-of-the-day and end-of-the-night measurements (Fig. 2, E and F). In contrast, GA deprivation increased malate and fumarate levels by approximately 1.5-fold in plants grown under ambient [CO2] at the end of the day, similar to changes we observed previously (Ribeiro et al., 2012), but not in plants grown under elevated [CO2]. By contrast, malate and fumarate levels were lower in rosettes of low-GA plants at the end of the night under ambient [CO2] (Fig. 2, E and F). Thus, the differential malate and fumarate pools induced by PAC treatment at ambient [CO2] were absent at elevated levels of [CO2].

Figure 2.

Levels of sugars, starch, malate, and fumarate in plants treated with PAC and/or GA. Carbohydrates and organic acids were measured in rosettes at the end of the light period (white sectors) and the end of dark period (gray sectors) in material harvested from plants grown at 350 or 750 µmol CO2 mol−1. A, Fru. B, Glc. C, Suc. D, Starch. E, Malate. F, Fumarate. G, Rate of starch accumulation. H, Rate of accumulation of sugars (sum of Suc, Glc, and Fru). I, Rate of malate accumulation. J, Rate of fumarate accumulation. Accumulation rates were calculated from the net difference in metabolite contents at the end of the night and the end of the day. Asterisks indicate values determined by Student’s t test to be significantly different from control plants at the shown [CO2] (P < 0.05). Values are means ± se of four independent experiments. FW, Fresh weight.

Starch and sugar turnover were calculated by subtracting the end-of-the-night from the end-of-the-day values (Cross et al., 2006). The GA regime did not influence the pool size of starch at either the end of the day or the end of the night; therefore, the turnover of these pools was unaltered. It should be noted, however, that PAC treatment tended to increase starch turnover at elevated [CO2] as compared with control plants, while no PAC effect was evident at ambient [CO2] (Fig. 2, G and H). The GA regime under ambient or elevated [CO2] had no significant effect on the turnover of sugars, with the exception of PAC- plus GA-treated plants, where sugar turnover increased at ambient [CO2] compared with the control (Fig. 2, A–C and H). Elevated [CO2] did not affect the turnover of fumarate and malate. However, rates of malate and fumarate turnover were markedly increased in low-GA plants grown at ambient [CO2] (Fig. 2, I and J), which were restored by growth at elevated [CO2].

Enhanced [CO2] Modifies Nitrogen Metabolism in Response to GA

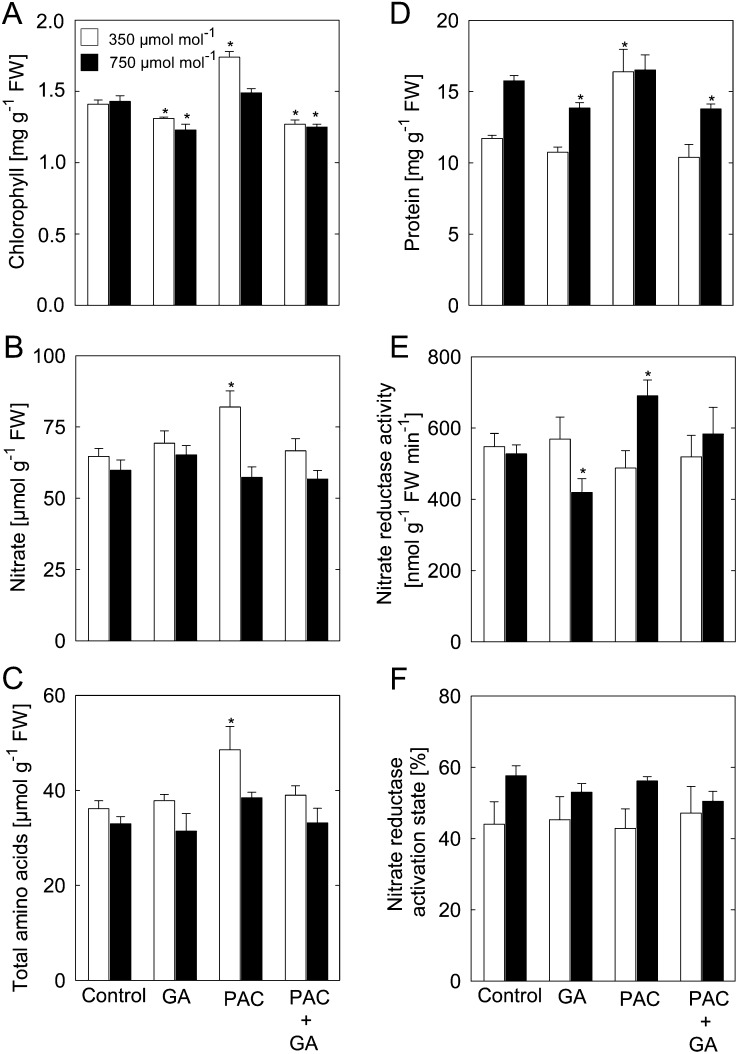

At ambient [CO2], the levels of chlorophyll, nitrate, total amino acids, and protein increased in plants treated with PAC (Fig. 3, A–D), but these effects were not apparent at elevated [CO2] (Bae and Sicher, 2004). Interestingly, chlorophyll and protein contents were slightly reduced in plants treated with GA alone, or PAC plus GA, under elevated [CO2] (Fig. 3, A and D), indicating that the GA response was not saturated under high [CO2] and, second, that GA acts, at least partially, independent of the [CO2].

Figure 3.

Levels of chlorophyll, nitrate, total amino acids, protein, and NR activity in plants treated with PAC and/or GA. A, Chlorophyll. B, Nitrate. C, Total amino acids. D, Protein. E, NR activity. F, NR activation state. Measurements were done using rosettes harvested at the end of the light period from plants grown at 350 or 750 µmol CO2 mol−1. Asterisks indicate values determined by Student’s t test to be significantly different from the control plants at the shown [CO2] (P < 0.05). Values are means ± se of four independent experiments. FW, Fresh weight.

At ambient [CO2], nitrate reductase (NR) activity was unaffected in shoots of plants treated with PAC and/or GA (Fig. 3E). However, NR activity increased by 31% in PAC-treated plants grown under elevated [CO2] as compared with untreated control plants. In addition, at elevated [CO2], NR activity decreased in plants treated with GA alone as compared with the untreated controls. However, NR activation state was neither significantly affected by the GA regime at ambient [CO2] nor at elevated [CO2] (Fig. 3F).

Analysis of the Influence of a Modified GA Regime on Enzyme Activities in Central Metabolism

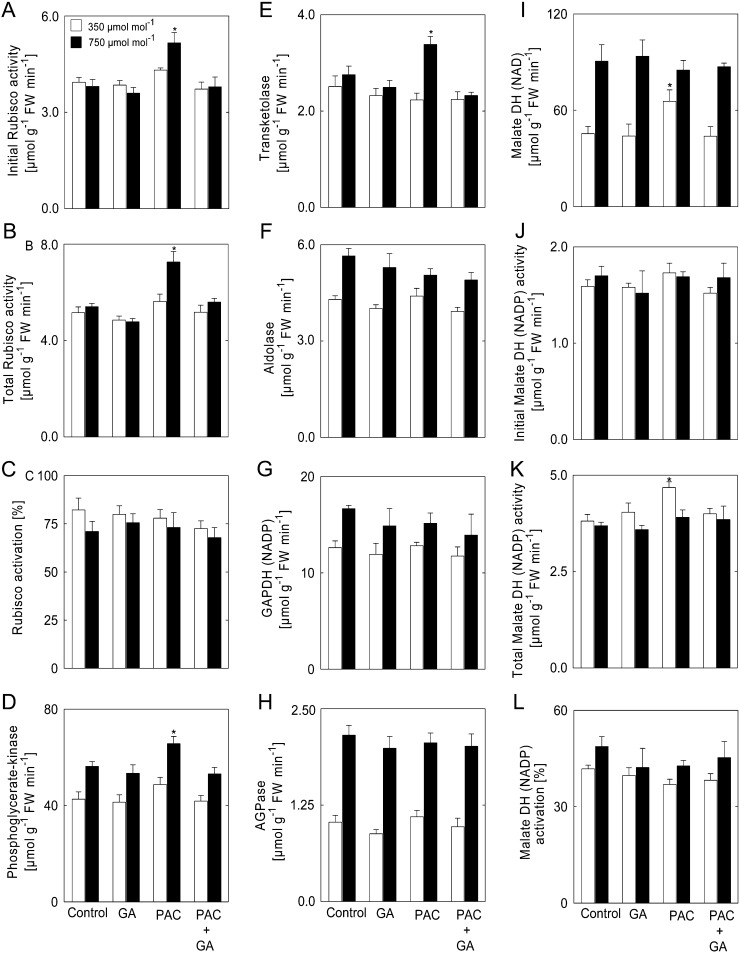

At ambient [CO2], the initial extractable activity of Rubisco (which is dependent on the amount of Rubisco and its state of activation) remained unaltered in low-GA (PAC treatment) and high-GA (GA treatment) plants as compared with the control (Fig. 4A). Moreover, total Rubisco activity (the maximum activity after in vitro activation) was independent of the GA regime in plants grown under ambient [CO2] (Fig. 4B). By contrast, the effect of elevated [CO2] on Rubisco activity depended on the GA regime. Elevated [CO2] led to a marked increase of Rubisco activity in PAC-treated plants, with initial and total Rubisco activities being enhanced by approximately 35% (Fig. 4, A and B). However, the GA regime did not affect the activation state of Rubisco (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Enzyme activities in shoots of plants treated with PAC and/or GA. A, Initial Rubisco activity. B, Total Rubisco activity. C, Rubisco activation. D, PGK. E, TK. F, Aldolase. G, GAPDH (NADP). H, AGPase. I, MDH (NAD). J, Initial MDH (NADP) activity. K, Total MDH (NADP) activity. L, MDH (NADP) activation. Measurements were done using Arabidopsis rosettes at the end of the light period from plants grown at 350 or 750 µmol CO2 mol−1. Asterisks indicate values determined by Student’s t test to be significantly different from the control plants at the shown [CO2] (P < 0.05). Values are means ± se of four independent experiments. FW, Fresh weight.

To better understand the above-described changes in growth and metabolites, we next analyzed the maximal activities of other key enzymes of central metabolism. At ambient [CO2], the activities of the Calvin-Benson cycle enzymes phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) and transketolase (TK) in plants treated with PAC and/or GA were similar to control plants (Fig. 4, D and E). By contrast, at elevated [CO2], PGK and TK activities increased significantly in PAC-treated plants, while they remained unaffected in plants exposed to GA, or PAC plus GA, as compared with the control. On the other hand, the activities of aldolase, NADP-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase) were increased at elevated [CO2] but unaffected by the different GA regimes (Fig. 4, F–H).

Since malate levels are altered by PAC treatment at ambient [CO2] (Fig. 2, E and F), we next determined the activity of NAD-dependent malate dehydrogenase (MDH). As expected, under ambient [CO2], the NAD-MDH activity was increased under GA-limiting conditions in the Arabidopsis shoots (Fig. 4I). On the other hand, NAD-MDH activity in shoots of low-GA plants was similar to that of high-GA and control plants in elevated [CO2] (Fig. 4I). We also assayed both initial and maximal activities of NADP-dependent MDH, and from these data, we calculated the activation state of the enzyme. The results revealed that initial NADP-MDH activity was unaltered in plants treated with PAC and/or GA both at ambient and elevated [CO2] (Fig. 4J). At ambient [CO2], total NADP-MDH activity was increased in plants grown in the environment that limited GA biosynthesis, while at elevated [CO2], the total NADP-MDH activity was similar to that observed in control plants (Fig. 4K). Moreover, no change in the activation state of NADP-MDH was observed in shoots of plants treated with PAC and/or GA grown both at ambient and elevated [CO2] (Fig. 4L).

Elevated [CO2] and alteration to the GA regime both led to changes in the overall protein content (Fig. 3D). We next investigated the relationship between the variation in the activities of individual enzymes (Figs. 3 and 4) and the variation in total leaf protein. The activities of the enzymes, therefore, were expressed on a leaf protein basis and the percentage change in elevated [CO2] was calculated (Table I). The activities of GAPDH (NADP), AGPase, and aldolase were increased by elevated [CO2] independent of the GA status. Elevated [CO2] led to increases in the activities of Rubisco (initial and total activities), PGK, NR, and TK in PAC-treated plants, but no effect of GA application on the activities of these enzymes was observed. Furthermore, elevated [CO2] resulted in decreased NAD-MDH activity (32%) and total NADP-MDH activity (18%) in shoots of low-GA plants. Even though elevated [CO2] restored plant growth at the physiological level for PAC-treated plants, the metabolic signature largely deviates from control plants.

Table I. Normalized changes of activities of enzymes in plants treated with PAC and/or GA grown at 350 or 750 µmol CO2 mol−1.

For each treatment (Figs. 3 and 4), the activities were related to protein and the activity of 750 µmol CO2 mol−1 was divided by the activity of 350 µmol CO2 mol−1. Values in boldface were determined by Student’s t test to be significantly different from the control. Values are means ± se of four independent experiments.

| Enzyme Activity (Activity in Elevated CO2 as a Percentage of Ambient CO2) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | Control | GA | PAC | PAC + GA |

| Rubisco, initial | 101.3 ± 7.3 | 104.9 ± 9.4 | 126.5 ± 5.3 | 110.4 ± 9.5 |

| Rubisco, total | 103.1 ± 4.0 | 109.3 ± 4.4 | 137.7 ± 7.1 | 115.7 ± 10.8 |

| GAPDH (NADP) | 126.7 ± 9.0 | 118.3 ± 10.1 | 126.0 ± 10.2 | 113.5 ± 8.7 |

| AGPase | 224.4 ± 13.9 | 252.1 ± 15.5 | 221.9 ± 13.0 | 243.5 ± 17.5 |

| TK | 109.8 ± 9.0 | 123.2 ± 9.4 | 162.6 ± 8.3 | 109.8 ± 5.9 |

| Aldolase | 120.9 ± 5.7 | 118.0 ± 6.5 | 120.8 ± 8.1 | 127.7 ± 9.1 |

| PGK | 111.4 ± 4.7 | 118.1 ± 6.7 | 148.2 ± 7.2 | 129.6 ± 6.8 |

| NR | 96.6 ± 8.0 | 104.2 ± 10.3 | 151.8 ± 8.9 | 109.1 ± 8.8 |

| MDH (NAD) | 220.2 ± 17.9 | 254.4 ± 20.8 | 149.1 ± 12.0 | 201.0 ± 15.7 |

| MDH (NADP), initial | 104.5 ± 4.9 | 106.6 ± 7.2 | 104.6 ± 4.4 | 119.3 ± 10.6 |

| Total | 98.5 ± 4.6 | 100.7 ± 9.1 | 81.1 ± 5.1 | 103.3 ± 6.3 |

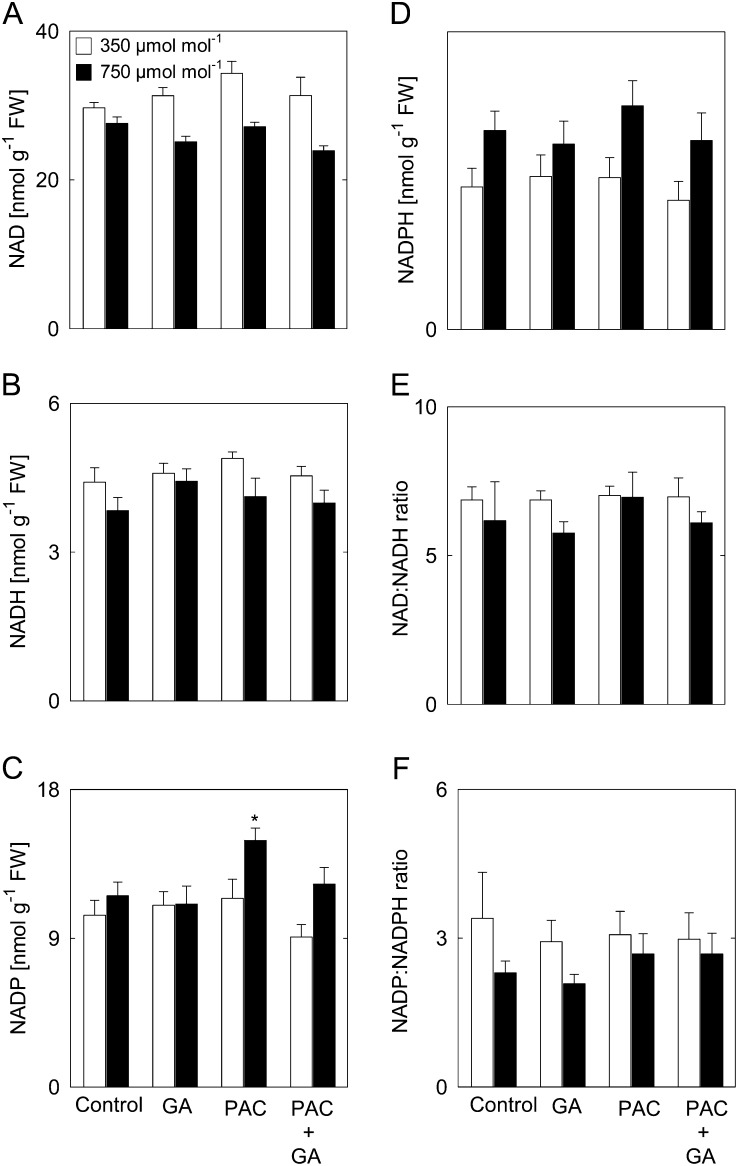

Effect of Enhanced [CO2] on the Pyridine Nucleotide Content in Response to GA

The maintenance of a balanced redox status affects the coordination of carbon and nitrogen assimilation and thus biomass accumulation (Nunes-Nesi et al., 2010; Hebbelmann et al., 2012). The levels of pyridine dinucleotides in leaves of plants treated with PAC and/or GA, both in ambient and elevated [CO2], were determined. Levels of NAD and NADH were unaltered between treatments at both [CO2] (Fig. 5, A and B). There was a significant 29% increase of NADP in plants treated with PAC at elevated [CO2] but not in plants treated with GA or PAC plus GA (Fig. 5C). Next to that, elevated [CO2] resulted in an increase in the levels of NADPH in all treatments (Fig. 5D). In ambient [CO2], NADP(H) levels were essentially unaltered in low- and high-GA plants (Fig. 5, C and D). In addition, the NAD/NADH and NADP/NADPH ratios were similar in controls and plants treated with PAC and/or GA (Fig. 5, E and F). Therefore, it seems that neither [CO2] nor GA significantly influences the metabolic redox balance (Fig. 5C). However, PAC treatment did result in increased levels of NADP at elevated [CO2], correlating with the increased activities of the Calvin-Benson cycle enzymes described above.

Figure 5.

Pyridine nucleotide levels in shoots of Arabidopsis plants treated with PAC and/or GA. A, NAD. B, NADH. C, NADP. D, NADPH. E, NAD/NADH ratio. F, NADP/NADPH ratio. Levels were measured in rosettes at the end of the light period in material harvested from plants grown at 350 or 750 µmol CO2 mol−1. Asterisks indicate values determined by Student’s t test to be significantly different from the control plants at the shown [CO2] (P < 0.05). Values are means ± se of four independent experiments. FW, Fresh weight.

Enhanced [CO2] Leads to a General Change in Leaf Metabolism of Plants Growing under Different GA Regimes

The effects of both elevated CO2 (Li et al., 2006) and GA regime (Ribeiro et al., 2012) on primary metabolism have been studied in Arabidopsis; however, as yet, the combined effect of both has not been analyzed. Metabolites were measured at the end of the day (Supplemental Table S1). Under ambient [CO2], PAC treatment increased the levels of 15 metabolites and decreased 12, while treatment with GA resulted in increases of 11 metabolites and decreases in six. Among the measured metabolites, erythritol, glyceric acid, Gly, homo-Ser, threitol, and threonic acid were increased upon GA treatment but decreased by PAC, while Rha, Suc, and tartaric acid showed an opposite pattern. Elevated [CO2] affected the levels of 21 metabolites, of which 10 were up-regulated, while 11 showed a lower level as compared with that at ambient [CO2]. At the phenotypic level, elevated [CO2] overcomes the growth inhibition of PAC. At the metabolic level, 17 of the 27 metabolites affected under ambient [CO2] were restored, while 10 were specifically affected by PAC treatment irrespective of [CO2]. On the other hand, of the GA-affected metabolites under ambient [CO2], eight were restored to control levels under elevated [CO2], while nine remained affected by the additional GA. We classified metabolites that are affected both by PAC and GA, but not by [CO2], as GA specific. This group includes erythritol, Rha, threitol, and tartaric acid (Supplemental Table S1). Metabolites specifically regulated by [CO2] (GA independently) include benzoic acid, glyceraldehyde-3-P, Gly, itaconic acid, myoinositol, maltose, mannitol, Orn, Phe, Tyr, Thr, putrescine, and trehalose. Interestingly, all metabolites affected by PAC under ambient [CO2], including dehydroascorbic acid, galactonic acid, gluconic acid, and pyro-Glu, were restored by elevated [CO2]. Similarly, metabolites only affected by increased GA under ambient [CO2], such as alloinositol, Met, and putrescine, were also restored by elevated [CO2].

Although elevated [CO2] restored at least 50% of the metabolic differences caused by the altered GA regime under ambient [CO2], it has to be noted that PAC treatment additionally affected the levels of 10 metabolites specifically at high [CO2]. Similarly, high GA levels affected eight metabolites only under elevated [CO2] conditions. Interestingly, the levels of Val and icatonic acid were reduced by GA but increased by PAC during elevated [CO2] conditions.

Effect of Elevated [CO2] on the Expression Profiles of GA-Related Genes

To investigate whether transcriptional regulation of GA metabolism and signaling had been modified by CO2 availability, we quantified the mRNA expression of genes encoding proteins involved in GA biosynthesis (KO, KAO1, GA20ox1–GA20ox3, GA3ox1, and GA3ox2), catabolism (GA2ox1–GA2ox3), and signaling (GID1B, RGL1, RGL2, RGL3) in plants with low- and high-GA levels grown at ambient or elevated [CO2]. First of all, we did not observe any significant change in expression (fold change ≥ 1) of GA-related genes under elevated [CO2] (Supplemental Table S2), indicating that GA homeostasis was only weakly affected under our experimental conditions. Next to that, the level of CO2 did not affect the response of GA-related genes toward exogenous application of GA. The transcriptional changes of genes involved in GA biosynthesis, catabolism, and signaling induced by GA were comparable to those of plants under ambient [CO2], although the responsiveness of the genes was reduced (Table II). As stated above, elevated [CO2] did not result in a saturation of the GA response. Similarly, the feedback up-regulation (GA biosynthesis genes and GID1B) and feed-forward down-regulation (GA catabolism genes and RGL1, RGL2, and RGL3) of the majority of mRNAs by PAC application still occurred under elevated [CO2], albeit with a weakened expressional change as compared with ambient [CO2] (Table II). Next to that, the combined application of GA and PAC resulted in a similar expressional response under both ambient and elevated [CO2] (Table II). These results indicate that [CO2] has only a small effect on the transcriptional feedback and feed-forward mechanisms that are determined by GA level.

Table II. Expression of GA-related genes in plants treated with PAC and/or GA grown at 350 or 750 µmol CO2 mol−1.

Asterisks indicate significant differences in gene expression between ambient and elevated [CO2], as determined by Student's t test (P < 0.05). Values in boldface were determined to be significantly different from the control. Values are means ± se of three independent replicates.

| Log2 (Treatment − Control) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis Genome Initiative Identifier | Name | 350 µmol CO2 mol−1 |

750 µmol CO2 mol−1 |

Ambient CO2 versus High CO2 |

||||||

| GA | PAC | PAC + GA | GA | PAC | PAC + GA | GA | PAC | PAC + GA | ||

| At5g25900 | KO | −0.51 ± 0.04 | 1.29 ± 0.06 | −0.17 ± 0.04 | −0.42 ± 0.07 | 0.84 ± 0.11 | −0.13 ± 0.02 | 1.21 | 1.53* | 1.31 |

| At1g05160 | KAO1 | −0.47 ± 0.08 | 0.57 ± 0.04 | −0.34 ± 0.05 | −0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.07 | −0.28 ± 0.04 | 1.20 | 1.78* | 1.21 |

| At4g25420 | GA20ox1 | −2.47 ± 0.25 | 2.59 ± 0.06 | −3.36 ± 0.49 | −2.23 ± 0.11 | 1.80 ± 0.11 | −2.83 ± 0.17 | 1.11 | 1.44* | 1.19 |

| At5g51810 | GA20ox2 | −4.95 ± 0.43 | 5.00 ± 0.16 | −5.24 ± 0.37 | −4.70 ± 0.39 | 3.65 ± 0.24 | −4.30 ± 0.52 | 1.05 | 1.37* | 1.22 |

| At5g07200 | GA20ox3 | −3.84 ± 0.31 | 4.83 ± 0.09 | −4.28 ± 0.20 | −3.79 ± 0.23 | 3.42 ± 0.13 | −3.93 ± 0.27 | 1.01 | 1.41* | 1.09 |

| At1g15550 | GA3ox1 | −2.86 ± 0.07 | 3.06 ± 0.23 | −2.90 ± 0.19 | −2.47 ± 0.12 | 2.14 ± 0.17 | −2.78 ± 0.34 | 1.16 | 1.43* | 1.04 |

| At1g80340 | GA3ox2 | −0.58 ± 0.04 | 1.64 ± 0.13 | −1.29 ± 0.15 | −0.51 ± 0.06 | 1.47 ± 0.13 | −0.78 ± 0.07 | 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.65* |

| At1g78440 | GA2ox1 | 0.74 ± 0.10 | −3.48 ± 0.34 | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 0.62 ± 0.07 | −1.84 ± 0.12 | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 1.19 | 1.89* | 1.07 |

| At1g30040 | GA2ox2 | 0.84 ± 0.11 | −2.03 ± 0.21 | 1.35 ± 0.07 | 0.68 ± 0.03 | −0.72 ± 0.12 | 1.29 ± 0.10 | 1.23 | 2.82* | 1.05 |

| At2g34555 | GA2ox3 | 1.34 ± 0.10 | −0.46 ± 0.05 | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 0.85 ± 0.07 | −0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.05 | 1.58* | 1.77* | 1.06 |

| At3g63010 | GID1B | −1.18 ± 0.11 | 3.04 ± 0.13 | −0.45 ± 0.14 | −0.67 ± 0.06 | 1.96 ± 0.21 | −0.39 ± 0.02 | 1.76* | 1.55* | 1.15 |

| At1g66350 | RGL1 | 0.44 ± 0.06 | −1.37 ± 0.07 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.01 | −1.17 ± 0.09 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 1.05 | 1.17 | 1.09 |

| At3g03450 | RGL2 | 0.82 ± 0.09 | −1.32 ± 0.20 | 0.64 ± 0.08 | 0.57 ± 0.04 | −0.54 ± 0.06 | 0.51 ± 0.08 | 1.44* | 2.44* | 1.25 |

| At5g17490 | RGL3 | 1.03 ± 0.08 | −1.15 ± 0.06 | 1.22 ± 0.11 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | −0.73 ± 0.05 | 0.70 ± 0.10 | 1.08 | 1.57* | 1.74* |

Changes in the Expression of Genes Associated with Cell Wall and Lipid Metabolism Mirror Plant Growth

In order to evaluate to what extent elevated [CO2] affects plant growth, we studied the expression of GA-responsive genes, which were selected on the basis of our previous expression study (Ribeiro et al., 2012). [CO2] itself had only a minor effect on the expression of these genes (Supplemental Table S2). At ambient [CO2], GA deprivation mainly resulted in a decrease of the expression of genes associated with cell wall and lipid metabolism, while the expression of these genes was up-regulated after GA treatment (Table III). A completely different picture emerged when PAC-treated plants were grown at elevated [CO2]. Expansins and xyloglucan endotransglucosylases/endohydrolases (XTHs) represent two major protein classes involved in driving cell expansion (Cosgrove, 2000; Van Sandt et al., 2007; Goh et al., 2012). In elevated [CO2], expansin and XTH genes showed an up-regulation upon GA deprivation, whereas PAC treatment down-regulated these genes at ambient [CO2] (Table III). Moreover, treatment with GA, or PAC plus GA, led to an increase in the expression of expansin and XTH genes in plants grown at ambient [CO2] but not in plants grown at elevated [CO2]. The changes in the expression of genes associated with cell wall and lipid metabolism correlated with the differences in growth rate. Therefore, the restoration of growth of PAC-treated plants by elevated [CO2] might be driven by a direct effect on the expression of cell elongation genes rather than GA metabolic genes.

Table III. Cell wall-related genes and genes involved in lipid metabolism affected by GA level in shoots of Arabidopsis plants grown at 350 or 750 µmol CO2 mol−1.

Values in boldface were determined by Student’s t test to be significantly different from the control (P < 0.05). Values are means ± se of three independent replicates.

| Log2 (Treatment − Control) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis Genome Initiative Identifier | Name | Description | 350 µmol CO2 mol−1 |

750 µmol CO2 mol−1 |

||||

| Cell wall | ||||||||

| At1g03870 | FLA9 | Fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein9 | 0.75 ± 0.08 | −1.49 ± 0.07 | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 0.88 ± 0.11 | 0.71 ± 0.12 | 0.60 ± 0.09 |

| At4g37800 | XTH7 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase7 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | −0.79 ± 0.10 | 0.87 ± 0.18 | −0.16 ± 0.02 | 1.32 ± 0.09 | 1.95 ± 0.05 |

| At1g11545 | XTH8 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase8 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | −1.29 ± 0.03 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 0.66 ± 0.05 | 1.66 ± 0.15 | 0.56 ± 0.07 |

| At5g57560 | XTH22 | Cell wall-modifying enzyme | 1.20 ± 0.08 | −0.66 ± 0.07 | 1.31 ± 0.13 | 1.14 ± 0.14 | 1.45 ± 0.07 | 1.20 ± 0.11 |

| At1g69530 | EXPA1 | α-Expansin gene family | 0.64 ± 0.04 | −2.24 ± 0.13 | 1.35 ± 0.12 | −0.31 ± 0.04 | 1.22 ± 0.13 | 0.39 ± 0.04 |

| At2g40610 | EXPA8 | α-Expansin gene family | 1.42 ± 0.11 | −4.65 ± 0.10 | 0.90 ± 0.07 | 0.83 ± 0.11 | 2.97 ± 0.32 | 0.19 ± 0.04 |

| At3g45970 | EXPL1 | Expansin-like | 1.28 ± 0.14 | −1.94 ± 0.17 | 2.05 ± 0.14 | 1.19 ± 0.15 | 1.70 ± 0.18 | 1.14 ± 0.12 |

| At3g57270 | BG1 | Member of glycosyl hydrolase family17 | 1.76 ± 0.20 | −3.36 ± 0.32 | −1.68 ± 0.13 | −0.68 ± 0.06 | 2.52 ± 0.10 | 0.42 ± 0.03 |

| At2g32540 | CSLB4 | Cellulose synthase-like B4 | 0.65 ± 0.12 | −1.12 ± 0.05 | 1.88 ± 0.12 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.60 ± 0.09 | 0.47 ± 0.11 |

| At2g20870 | Cell wall protein precursor | 1.64 ± 0.11 | 2.93 ± 0.18 | −0.63 ± 0.11 | 0.94 ± 0.07 | 1.33 ± 0.08 | 1.08 ± 0.12 | |

| Lipid metabolism | ||||||||

| At3g56060 | Glc-methanol-choline oxidoreductase | 0.99 ± 0.15 | −2.10 ± 0.14 | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 0.63 ± 0.06 | 2.81 ± 0.27 | 0.77 ± 0.08 | |

| At4g18970 | GDSL-like lipase/acylhydrolase | 1.33 ± 0.08 | −2.16 ± 0.22 | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 2.34 ± 0.21 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | |

| At4g28780 | GDSL-like lipase/acylhydrolase | 0.18 ± 0.01 | −3.11 ± 0.33 | 0.27 ± 0.09 | 0.51 ± 0.12 | 1.50 ± 0.07 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | |

| At4g39670 | Glycolipid transfer protein (GLTP) family protein | −0.43 ± 0.06 | −3.85 ± 0.16 | −3.08 ± 0.20 | −0.41 ± 0.04 | −2.09 ± 0.08 | −2.07 ± 0.15 | |

DISCUSSION

The initial reason for testing the interaction between GA regime and CO2 was the observation that at ambient [CO2], PAC uncoupled growth from carbon availability (Ribeiro et al., 2012). So far, there is a general consensus that elevated [CO2] increases carbon uptake and foliar carbohydrate content and, thereby, stimulates plant growth (Ainsworth et al., 2002; Kirschbaum, 2011). Here, we found that growth inhibition induced by PAC is overcome by elevated [CO2]. Although GA homeostasis as determined at the transcript level is hardly affected by high [CO2], reprogramming at the metabolic level occurs concomitantly with the induction of GA-responsive growth-related genes. Taken together, our observations suggest that increased [CO2] stimulates growth at least in part in a GA-independent manner.

Expression of Growth-Related Genes Is Uncoupled from GA Status at Elevated [CO2]

In an attempt to clarify the effect of elevated [CO2] on GA metabolism and growth, the expression of GA biosynthesis and signaling genes was analyzed in plants treated with PAC and/or GA grown under ambient or elevated [CO2]. PAC treatment at both ambient [CO2] and elevated [CO2] resulted in a similar activation of GA biosynthesis gene expression, suggesting that GA biosynthesis is still affected by PAC at elevated [CO2]. Similarly, the feedback repression of GID1B, encoding a GA receptor protein (Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2007), as well as RGL2 and RGL3, encoding DELLA proteins, by PAC is observed under both ambient and elevated [CO2]. Moreover, the addition of external GA to plants grown under elevated [CO2] provokes a similar expressional response to that under ambient levels. Thus, increased [CO2] does not affect the transcriptional responsiveness of the plants toward this phytohormone. Moreover, elevated [CO2] alone did not significantly affect the expression level of GA-related genes as compared with ambient [CO2], indicating that the effect of [CO2] on plant growth might be independent of changes in the transcription of GA biosynthesis genes.

Cell growth involves the selective loosening and rearrangement of the cell wall to provoke a turgor-driven expansion (Marga et al., 2005). Expansins (Goh et al., 2012) and XTHs (Van Sandt et al., 2007) are the best characterized protein classes known to drive this process. Previously, we found that GA and PAC have opposing effects on the expression of these genes under ambient [CO2], fitting to the expansion rates of the plants (Ribeiro et al., 2012). In contrast, a remarkable increase in the expression of these genes was observed after PAC treatment under elevated [CO2], while GA treatment no longer induced the expression of these genes when plants were grown at high [CO2]. Thus, under high [CO2], the GA regime no longer controls the expression of these growth-related genes. Interestingly, a similar observation was made for genes involved in lipid metabolism. Recently, it was found that brassinosteroids are the main effectors that induce growth-related genes, whereas GA quantitatively enhances brassinosteroid-potentiated growth (Bai et al., 2012), suggesting that the induction of these genes during elevated [CO2] might depend on brassinosteroids. Taken together, the expressional analysis suggests that under high carbon availability, plant growth might be uncoupled from GA status.

Growth and Source versus Sink Limitation

The decreases in relative growth rate, relative expansion rate, fresh weight, and dry weight in shoots of PAC-treated plants under ambient [CO2] were overcome when PAC-treated plants were grown in elevated [CO2]. These results indicate an involvement of elevated [CO2] in alleviating GA deficiency-induced responses. Leaf growth is known to be highly dependent on carbon availability (Wiese et al., 2007; Pantin et al., 2011). Three of the five Calvin-Benson cycle enzymes that we investigated (Rubisco, PGK, and TK) showed an increase in activity in low-GA plants under elevated [CO2]. Although this suggests that photosynthetic carbon assimilation is increased in PAC-treated plants, it is the developmental program itself that determines how efficiently carbon is converted into biomass (Sulpice et al., 2010). Still, low-GA plants grown under elevated [CO2] maintained carbon gain. Furthermore, the activity of NR also remained high in plants treated with PAC under elevated [CO2]. In ambient [CO2], the level of nitrate accumulated in plants treated with PAC but not in other treatments. On the other hand, at elevated [CO2], nitrate remained at the same level in low- or high-GA plants as compared with control plants. This highlights the ability of plants growing under the low-GA regime to invest inorganic nitrogen to support the light-dependent use of CO2 to produce sugars, organic acids, and amino acids, the basic building blocks of biomass accumulation.

It is known that malate and fumarate serve as alternative and flexible sinks for photosynthate in Arabidopsis (Chia et al., 2000; Pracharoenwattana et al., 2010; Zell et al., 2010). Two sets of observations showed that diurnal malate and fumarate turnover was highly regulated in low-GA plants grown at ambient [CO2]. First, in low-GA plants, only small amounts of malate and fumarate were left at the end of the night. Second, a larger proportion of the organic acids accumulated during the day in low-GA plants grown under ambient [CO2], although these plants also exhibited the greatest growth inhibition. These observations indicate that organic acid synthesis corresponds to changes of the sink-source balance. In agreement with this model, GA was able to recover the growth of plants treated with PAC, and this was accompanied by decreases in malate and fumarate levels in plants grown under ambient [CO2]. Furthermore, the high levels of organic acid during the day in plants treated with PAC grown under ambient [CO2] were not maintained under elevated [CO2], correlating with the differences in growth rate.

Rubisco adds CO2 to ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate to form glycerate-3-P in the first step of carbon fixation. The majority of the NADPH and ATP produced in the light reactions are used to reduce glycerate-3-P to triose phosphates. Triose phosphates are used to regenerate ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate and to synthesize end products such as Suc, starch, and amino acids (Stitt et al., 2010). Thus, the increased level of NADP observed in plants treated with PAC grown at elevated [CO2] indicates that NADPH is being utilized more rapidly when low-GA plant growth is stimulated by elevated [CO2]. In agreement with this model, there were no significant differences in Rubisco activities (initial and total) and NADP(H) levels in plants treated with PAC and/or GA under ambient [CO2]. The turnover of soluble sugars and starch that are usually considered to be diagnostic for the regulation of photosynthesis (Stitt et al., 2010) was not affected by GA level (PAC and/or GA treatment) both in plants grown in ambient and elevated [CO2]. Thus, the carbon status in shoots of low-GA plants grown under ambient [CO2] can be interpreted as the result of the rosette expansion being more reduced than carbon inflow. These data indicate that carbon only leads to extra growth if plants have a use for it (e.g. for the growth of new sinks such as leaves or roots). GA addition creates such an additional developmental force and completely rescues the rosette growth of PAC-treated plants in ambient [CO2]. At elevated [CO2], there was a substantial stimulation of sugar and starch synthesis in plants treated with PAC and/or GA, similar to the control. The stimulation of starch synthesis is accompanied by an increase of AGPase activity, irrespective of the GA regime. Most importantly, elevated [CO2] increased the biomass accumulation of plants with the restriction of GA biosynthesis, and the turnover of soluble sugars and starch was increased as compared with plants at ambient [CO2]. These results provide compelling evidence that under elevated [CO2], the carbohydrates are readily used for growth or export in plants with low GA levels, as indicated by the expression of cell wall-related genes. Thus, growth is faster at elevated [CO2] in GA-limited plants, because the storage and allocation of assimilates are altered. We cannot, however, formally exclude the possibility that elevated [CO2] regulates growth by linking primary metabolism with enhanced GA biosynthesis, since there is evidence that elevated [CO2] increases the level of GA in plants such as Arabidopsis (Teng et al., 2006) and orchids (Li et al., 2002).

Metabolic Reprogramming during Growth at Elevated [CO2] Might Circumvent GA Biosynthesis

As indicated above, the growth of plants with differing GA regimes under elevated [CO2] only partially restores the metabolic profile, indicating a potential metabolic flexibility to restore plant growth. Previously, it has been reported that the metabolite levels of putrescine and trehalose positively correlate with plant biomass in Arabidopsis (Meyer et al., 2007). Our analysis here indicates that both trehalose and putrescine act independently of GA level and are both induced specifically by elevated [CO2] (Supplemental Table S1), correlating with the increased growth phenotype. Trehalose-6-P has been put forward as a signaling molecule of both carbon metabolism and plant development (Meyer et al., 2007; Paul et al., 2008).

The accumulation of Orn upon elevated [CO2] might be representative for the different water use efficiencies (Gonzàlez-Meler et al., 2009) of plants grown at high [CO2] and the relationship between Orn and water status (Kalamaki et al., 2009). For other metabolites, a negative correlation has been described between biomass accumulation and their levels (Meyer et al., 2007). Here, we found that three of them are specifically controlled by [CO2]: glyceraldehyde-3-P, Phe, and Tyr (Meyer et al., 2007). Of these growth markers, PAC treatment at ambient [CO2] only negatively affects the accumulation of trehalose, while the other [CO2]-regulated markers remain unchanged.

Of the GA-specific metabolites found here, including erythritol, Rha, threitol, and tartaric acid, none has so far been correlated with plant biomass accumulation. Rha is a major component of pectin (Ridley et al., 2001). As cell growth is to a large extent determined by the extension rate of the cell wall (Brown et al., 2001), it is not surprising to see a correlation between GA regime and Rha level. Erythritol represents an intermediate in the methylerythritol phosphate pathway (Suzuki et al., 2009), which is used to synthesize plastidic isoprenoids (e.g. carotenoids and the side chains of chlorophylls and plastoquinones) and some isoprenoid-type phytohormones (e.g. GAs, abscisic acid, and cytokinins). Therefore, the effect of GA on the erythritol level might represent a metabolic feedback regulation. That said, the limited number of GA-specific metabolites indicates that the effect of GA on carbon metabolism is probably additive or redundant with other major regulating factors.

A restoration of several metabolites affected by PAC treatment under ambient [CO2] is observed upon elevated [CO2]. However, other metabolites are affected by PAC and GA only at high [CO2]. Although no obvious phenotypic differences exist between control and PAC-treated plants at elevated [CO2], their metabolic profiles are clearly distinctive. This might indicate a certain metabolic flexibility at high [CO2] that allows for plant growth even under low-GA regimes. Most GA oxidases involved in controlling GA homeostasis are 2-oxoglutarate dependent, including the Arabidopsis GA3ox, GA20ox, and GA2ox enzymes, which use it as a cosubstrate (Hedden and Phillips, 2000; Mitchum et al., 2006). The dependence on 2-oxoglutarate thereby links GA biosynthesis directly with primary metabolism (Lancien et al., 2000). Interestingly, 2-oxoglutarate is a central regulator of metabolism and the integration point of carbon and nitrogen metabolism. 2-Oxoglutarate is not only a central metabolite in the tricarboxylic acid cycle but is also important for primary amino acid metabolism (Nunes-Nesi et al., 2010), nitrate assimilation, and linked to NR activity (Kinoshita et al., 2011) and the photorespiratory glyoxylate cycle (Igarashi et al., 2003). Altered uptake of 2-oxoglutarate into the chloroplast results in growth retardation (Taniguchi et al., 2002), emphasizing the role of 2-oxoglutarate in coupling plant growth with metabolism. Elevated [CO2] did not affect the level of the potential nitrogen storage molecule Arg (Llácer et al., 2008); however, PAC treatment resulted in a lower level of this compound under ambient [CO2], which is restored by high [CO2]. We believe that the restoration of growth by elevated [CO2] of PAC-treated plants occurs not merely by complementing the metabolic changes induced by PAC but more likely by a mechanism of metabolic flexibility (Eberhard et al., 2008; Hebbelmann et al., 2012). By contrast, 2-oxoglutarate-dependent GA metabolism would seem likely to be strictly controlled at ambient CO2 and, as such, may mediate the growth-promoting effect of GA under these conditions. Recently, it was found that reducing the activity of the enzyme 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) results in different levels of bioactive GA and corresponding developmental phenotypes (Araújo et al., 2012). That said, considerable further research on the interaction between 2-oxoglutarate, primary metabolism, and GAs is required to determine the precise mechanisms underlying this linkage.

CONCLUSION

We found that the ability to utilize increased carbon supply may influence the leaf expansion of low-GA plants grown under elevated [CO2]. This will play an important role in allowing higher growth rates at enhanced [CO2] under GA deprivation. One of the major questions for the future is to learn how the CO2 supply is sensed in low-GA plants and how the close coordination of growth and metabolism is achieved in plants grown in a changing environment. The spectacular increases in wheat and rice yields during the Green Revolution in the 1960s were enabled by the introduction of dwarfing traits, which we know now interfere with the action or production of the GAs (Peng et al., 1999). Since the 1960s, the level of atmospheric [CO2] has increased by 25% (Solomon et al., 2007); it will be interesting to investigate to what extent Earth’s future climate might be suited for productive agricultural production with current semidwarf crop varieties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth Conditions and Experimental Design

Wild-type seeds of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ecotype Columbia-0 were sown on standard greenhouse soil (Stender) in plastic pots with a 0.1-L capacity. The trays containing the pots were placed under a 12/12-h day/night cycle (22°C/16°C) with 60%/75% relative humidity and 150 μmol m−2 s−1 light intensity.

Despite the fact that a wide number of mutants have been characterized that contain altered GA biosynthesis (Yamaguchi, 2008), we chose to manipulate the GA content by using PAC in an attempt to minimize the influence of pleiotropic effects. This approach has already been successfully applied to a number of species, including Arabidopsis (Rademacher, 2000; Ribeiro et al., 2012). Thus, 14 d after sowing, plants grown singly in pots (0.1 L) were watered with 10 mL of PAC (Duchefa) solution (50 mg L−1, 0.5 mg pot−1). For GA treatment, each plant was sprayed every 2 d with 1 mL of 50 µm GA (Duchefa) containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 80. Three days after treatments, plants used in the assays were placed in trays in a random arrangement with 35 pots per tray and then transferred to climate chambers with a 12-h-light/12-h-night day/night cycle (22°C/16°C, 60%/75% relative humidity, and 150 μmol m−2 s−1 light intensity) under either ambient (350 ± 30 µmol mol−1) or elevated (750 ± 55 µmol mol−1) [CO2]. Harvests of 30 plants (six independent samples containing five whole rosettes) were performed at the end of the night period and at the end of the day period 28 d after sowing (14 d after the onset of PAC and/or GA treatment). The entire sample was powdered under liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use.

Determination of Metabolite Levels

Thirty plants (six independent samples containing five whole rosettes) were harvested per treatment and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Chlorophyll, Suc, starch, total protein, total amino acid, and nitrate contents were determined as described by Cross et al. (2006). Malate and fumarate contents were determined as described by Nunes-Nesi et al. (2007). The extraction and assay of NAD, NADH, NADP, and NADPH were performed according to the method described by Gibon and Larher (1997). The levels of all other metabolites were quantified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry exactly following the protocol described by Lisec et al. (2006).

Extraction and Assay of Enzymes

Frozen rosette powder (approximately 50 mg) was extracted by vigorous shaking with 1 mL of extraction buffer. The composition of extraction buffer was 20% (v/v) glycerol, 0.25% (w/v) bovine serum albumin, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 50 mm HEPES/KOH, pH 7.5, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm benzamidine, 1 mm ε-aminocaproic acid, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.5 mm dithiothreitol. NADP-MDH was assayed as described by Scheibe and Stitt (1988). NR, Rubisco, PGK, NADP-GAPDH, aldolase, TK, AGPase, and NAD-MDH were assayed as described by Gibon et al. (2004, 2006, 2009).

Complementary DNA Synthesis and Real-Time PCR Analysis

Complementary DNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNAs using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed on a 384-well plate with an ABI PRISM 7900 HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems), and amplification products were analyzed using SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems; Caldana et al., 2007; Balazadeh et al., 2008). PCR primers (Supplemental Table S3) were designed with the online tool QuantPrime (Arvidsson et al., 2008). Three biological replicates were processed for each experimental condition.

Statistical Analyses

All experiments were designed in a completely randomized distribution. Differences described are systematically statistically grounded based on ANOVA, where P < 0.05 was considered significant. If ANOVA showed significant effects, Student’s t test (P < 0.05) was used to determine differences between each treatment and control. All statistical analyses were made using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 8.0 for Windows statistical software (SPSS).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Table S1. Metabolite levels in plants grown at ambient and elevated [CO2].

Supplemental Table S2. Gene expression in control plants grown at ambient and elevated [CO2].

Supplemental Table S3. Sequences of primers used for quantitative reverse transcription-PCR.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karin Koehl and the Greenteam of the Max-Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology for their assistance with plant growth.

Glossary

- [CO2]

CO2 concentration

- PAC

paclobutrazol

- NR

nitrate reductase

- PGK

phosphoglycerate kinase

- TK

transketolase

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- AGPase

ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase

- MDH

malate dehydrogenase

- XTH

xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/endohydrolases

References

- Ainsworth EA. (2008) Rice production in a changing climate: a meta-analysis of responses to elevated carbon dioxide and elevated ozone concentrations. Glob Change Biol 14: 1642–1650 [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth EA, Davey PA, Bernacchi CJ, Dermody OC, Heaton EA, Moore DJ, Morgan PB, Naidu SL, Ra HSY, Zhu XG, et al. (2002) A meta-analysis of elevated [CO2] effects on soybean (Glycine max) physiology, growth and yield. Glob Change Biol 8: 695–709 [Google Scholar]

- Araújo WL, Tohge T, Osorio S, Lohse M, Balbo I, Krahnert I, Sienkiewicz-Porzucek A, Usadel B, Nunes-Nesi A, Fernie AR. (2012) Antisense inhibition of the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex in tomato demonstrates its importance for plant respiration and during leaf senescence and fruit maturation. Plant Cell 24: 2328–2351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson S, Kwasniewski M, Riaño-Pachón DM, Mueller-Roeber B. (2008) QuantPrime: a flexible tool for reliable high-throughput primer design for quantitative PCR. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H, Sicher R. (2004) Changes of soluble protein expression and leaf metabolite levels in Arabidopsis thaliana grown in elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide. Field Crops Res 90: 61–73 [Google Scholar]

- Bai MY, Shang JX, Oh E, Fan M, Bai Y, Zentella R, Sun TP, Wang ZY. (2012) Brassinosteroid, gibberellin and phytochrome impinge on a common transcription module in Arabidopsis. Nat Cell Biol 14: 810–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JT. (2004) Yield responses of southern US rice cultivars to CO2 and temperature. Agric For Meteorol 122: 129–137 [Google Scholar]

- Baker JT, Allen LH., Jr (1994) Assessment of the impact of rising carbon dioxide and other potential climate changes on vegetation. Environ Pollut 83: 223–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazadeh S, Riaño-Pachón DM, Mueller-Roeber B. (2008) Transcription factors regulating leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Biol (Stuttg) (Suppl 1) 10: 63–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DE, Rashotte AM, Murphy AS, Normanly J, Tague BW, Peer WA, Taiz L, Muday GK. (2001) Flavonoids act as negative regulators of auxin transport in vivo in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 126: 524–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldana C, Scheible WR, Mueller-Roeber B, Ruzicic S. (2007) A quantitative RT-PCR platform for high-throughput expression profiling of 2500 rice transcription factors. Plant Methods 3: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia DW, Yoder TJ, Reiter WD, Gibson SI. (2000) Fumaric acid: an overlooked form of fixed carbon in Arabidopsis and other plant species. Planta 211: 743–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. (2000) Loosening of plant cell walls by expansins. Nature 407: 321–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowling RJ, Kamiya Y, Seto H, Harberd NP. (1998) Gibberellin dose-response regulation of GA4 gene transcript levels in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 117: 1195–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross JM, von Korff M, Altmann T, Bartzetko L, Sulpice R, Gibon Y, Palacios N, Stitt M. (2006) Variation of enzyme activities and metabolite levels in 24 Arabidopsis accessions growing in carbon-limited conditions. Plant Physiol 142: 1574–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard S, Finazzi G, Wollman FA. (2008) The dynamics of photosynthesis. Annu Rev Genet 42: 463–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott RC, Smith JL, Lester DR, Reid JB. (2001) Feed-forward regulation of gibberellin deactivation in pea. J Plant Growth Regul 20: 87–94 [Google Scholar]

- Fleet CM, Sun TP. (2005) A DELLAcate balance: the role of gibberellin in plant morphogenesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol 8: 77–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibon Y, Blaesing OE, Hannemann J, Carillo P, Höhne M, Hendriks JHM, Palacios N, Cross J, Selbig J, Stitt M. (2004) A robot-based platform to measure multiple enzyme activities in Arabidopsis using a set of cycling assays: comparison of changes of enzyme activities and transcript levels during diurnal cycles and in prolonged darkness. Plant Cell 16: 3304–3325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibon Y, Larher F. (1997) Cycling assay for nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides: NaCl precipitation and ethanol solubilization of the reduced tetrazolium. Anal Biochem 251: 153–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibon Y, Pyl ET, Sulpice R, Lunn JE, Höhne M, Günther M, Stitt M. (2009) Adjustment of growth, starch turnover, protein content and central metabolism to a decrease of the carbon supply when Arabidopsis is grown in very short photoperiods. Plant Cell Environ 32: 859–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibon Y, Usadel B, Blaesing OE, Kamlage B, Hoehne M, Trethewey R, Stitt M. (2006) Integration of metabolite with transcript and enzyme activity profiling during diurnal cycles in Arabidopsis rosettes. Genome Biol 7: R76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh HH, Sloan J, Dorca-Fornell C, Fleming AJ. (2012) Inducible repression of multiple expansin genes leads to growth suppression during leaf development. Plant Physiol 159: 1759–1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzàlez-Meler MA, Blanc-Betes E, Flower CE, Ward JK, Gomez-Casanovas N. (2009) Plastic and adaptive responses of plant respiration to changes in atmospheric CO2 concentration. Physiol Plant 137: 473–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebbelmann I, Selinski J, Wehmeyer C, Goss T, Voss I, Mulo P, Kangasjärvi S, Aro EM, Oelze ML, Dietz KJ, et al. (2012) Multiple strategies to prevent oxidative stress in Arabidopsis plants lacking the malate valve enzyme NADP-malate dehydrogenase. J Exp Bot 63: 1445–1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P. (2003) The genes of the green revolution. Trends Genet 19: 5–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P, Phillips AL. (2000) Gibberellin metabolism: new insights revealed by the genes. Trends Plant Sci 5: 523–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell CA, Chandler PM, Poole A, Dennis ES, Peacock WJ. (2001) The CYP88A cytochrome P450, ent-kaurenoic acid oxidase, catalyzes three steps of the gibberellin biosynthesis pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 2065–2070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi D, Miwa T, Seki M, Kobayashi M, Kato T, Tabata S, Shinozaki K, Ohsumi C. (2003) Identification of photorespiratory glutamate:glyoxylate aminotransferase (GGAT) gene in Arabidopsis. Plant J 33: 975–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamaki MS, Alexandrou D, Lazari D, Merkouropoulos G, Fotopoulos V, Pateraki I, Aggelis A, Carrillo-López A, Rubio-Cabetas MJ, Kanellis AK. (2009) Over-expression of a tomato N-acetyl-L-glutamate synthase gene (SlNAGS1) in Arabidopsis thaliana results in high ornithine levels and increased tolerance in salt and drought stresses. J Exp Bot 60: 1859–1871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khush GS. (2001) Green revolution: the way forward. Nat Rev Genet 2: 815–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita H, Nagasaki J, Yoshikawa N, Yamamoto A, Takito S, Kawasaki M, Sugiyama T, Miyake H, Weber AP, Taniguchi M. (2011) The chloroplastic 2-oxoglutarate/malate transporter has dual function as the malate valve and in carbon/nitrogen metabolism. Plant J 65: 15–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum MUF. (2011) Does enhanced photosynthesis enhance growth? Lessons learned from CO2 enrichment studies. Plant Physiol 155: 117–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancien M, Gadal P, Hodges M. (2000) Enzyme redundancy and the importance of 2-oxoglutarate in higher plant ammonium assimilation. Plant Physiol 123: 817–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CR, Gan LJ, Xia K, Zhou X, Hew CS. (2002) Responses of carboxylating enzymes, sucrose metabolizing enzymes and plant hormones in a tropical epiphytic CAM orchid to CO2 enrichment. Plant Cell Environ 25: 369–377 [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Sioson A, Mane SP, Ulanov A, Grothaus G, Heath LS, Murali TM, Bohnert HJ, Grene R. (2006) Response diversity of Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes in elevated [CO2] in the field. Plant Mol Biol 62: 593–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisec J, Schauer N, Kopka J, Willmitzer L, Fernie AR. (2006) Gas chromatography mass spectrometry-based metabolite profiling in plants. Nat Protoc 1: 387–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llácer JL, Fita I, Rubio V. (2008) Arginine and nitrogen storage. Curr Opin Struct Biol 18: 673–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luomala EM, Laitinen K, Sutinen S, Kellomaki S, Vapaavuori E. (2005) Stomatal density, anatomy and nutrient concentrations of Scots pine needles are affected by elevated CO2 and temperature. Plant Cell Environ 28: 733–749 [Google Scholar]

- Marga F, Grandbois M, Cosgrove DJ, Baskin TI. (2005) Cell wall extension results in the coordinate separation of parallel microfibrils: evidence from scanning electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy. Plant J 43: 181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DN, Proebsting WM, Hedden P. (1999) The SLENDER gene of pea encodes a gibberellin 2-oxidase. Plant Physiol 121: 775–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masle J. (2000) The effects of elevated CO2 concentrations on cell division rates, growth patterns, and blade anatomy in young wheat plants are modulated by factors related to leaf position, vernalization, and genotype. Plant Physiol 122: 1399–1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehl GA, Stocker TF, Collins WD, Friedlingstein P, Gaye AT, Gregory JM, Kitoh A, Knutti R, Murphy JM, Noda A, et al. (2007) Global climate projections. In S Solomon, D Qin, M Manning, Z Chen, M Marquis, KB Averyt, M Tignor, HL Miller, eds, Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Meyer RC, Steinfath M, Lisec J, Becher M, Witucka-Wall H, Törjék O, Fiehn O, Eckardt A, Willmitzer L, Selbig J, et al. (2007) The metabolic signature related to high plant growth rate in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 4759–4764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton AM, Úbeda-Tomás S, Griffiths J, Holman T, Hedden P, Thomas SG, Phillips AL, Holdsworth MJ, Bennett MJ, King JR, et al. (2012) Mathematical modeling elucidates the role of transcriptional feedback in gibberellin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 7571–7576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchum MG, Yamaguchi S, Hanada A, Kuwahara A, Yoshioka Y, Kato T, Tabata S, Kamiya Y, Sun TP. (2006) Distinct and overlapping roles of two gibberellin 3-oxidases in Arabidopsis development. Plant J 45: 804–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y, Jin C, Jin G, Zhou Q, Lin X, Tang C, Zhang Y. (2011) Auxin modulates the enhanced development of root hairs in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. under elevated CO2. Plant Cell Environ 34: 1304–1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes-Nesi A, Carrari F, Gibon Y, Sulpice R, Lytovchenko A, Fisahn J, Graham J, Ratcliffe RG, Sweetlove LJ, Fernie AR. (2007) Deficiency of mitochondrial fumarase activity in tomato plants impairs photosynthesis via an effect on stomatal function. Plant J 50: 1093–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes-Nesi A, Fernie AR, Stitt M. (2010) Metabolic and signaling aspects underpinning the regulation of plant carbon nitrogen interactions. Mol Plant 3: 973–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, Hanada A, Yamauchi Y, Kuwahara A, Kamiya Y, Yamaguchi S. (2003) Gibberellin biosynthesis and response during Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant Cell 15: 1591–1604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski N, Sun TP, Gubler F. (2002) Gibberellin signaling: biosynthesis, catabolism, and response pathways. Plant Cell (Suppl) 14: S61–S80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin F, Simonneau T, Rolland G, Dauzat M, Muller B. (2011) Control of leaf expansion: a developmental switch from metabolics to hydraulics. Plant Physiol 156: 803–815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul MJ, Primavesi LF, Jhurreea D, Zhang Y. (2008) Trehalose metabolism and signaling. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59: 417–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Richards DE, Hartley NM, Murphy GP, Devos KM, Flintham JE, Beales J, Fish LJ, Worland AJ, Pelica F, et al. (1999) ‘Green revolution’ genes encode mutant gibberellin response modulators. Nature 400: 256–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S, Huang J, Cassmanc KG, Lazaa RC, Visperasa RM, Khushd GS. (2010) The importance of maintenance breeding: a case study of the first miracle rice variety-IR8. Field Crops Res 108: 32–38 [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AL. (2004) Genetic and transgenic approaches to improving crop performance. In PJ Davies, ed, Plant Hormones: Biosynthesis, Signal Transduction, Action! Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 582–609

- Pracharoenwattana I, Zhou W, Keech O, Francisco PB, Udomchalothorn T, Tschoep H, Stitt M, Gibon Y, Smith SM. (2010) Arabidopsis has a cytosolic fumarase required for the massive allocation of photosynthate into fumaric acid and for rapid plant growth on high nitrogen. Plant J 62: 785–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher W. (2000) Growth retardants: effects on gibberellin biosynthesis and other metabolic pathways. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 51: 501–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro DM, Araújo WL, Fernie AR, Schippers JH, Mueller-Roeber B. (2012) Translatome and metabolome effects triggered by gibberellins during rosette growth in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 63: 2769–2786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards DE, King KE, Ait-Ali T, Harberd NP. (2001) How gibberellin regulates plant growth and development: a molecular genetic analysis of gibberellin signalling. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 52: 67–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley BL, O’Neill MA, Mohnen DA. (2001) Pectins: structure, biosynthesis, and oligogalacturonide-related signaling. Phytochemistry 57: 929–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibe R, Stitt M. (1988) Comparison of NADP-malate dehydrogenase activation, QA reduction and O2 evolution in spinach leaves. Plant Physiol Biochem 26: 473–481 [Google Scholar]

- Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Chen Z, Marquis M, Averyt KB, Tignor M, Miller HL, editors (2007) Technical summary. In S Solomon, D Qin, M Manning, Z Chen, M Marquis, KB Averyt, M Tignor, HL Miller, eds, Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Annual Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Spielmeyer W, Ellis MH, Chandler PM. (2002) Semidwarf (sd-1), “green revolution” rice, contains a defective gibberellin 20-oxidase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 9043–9048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Lunn J, Usadel B. (2010) Arabidopsis and primary photosynthetic metabolism: more than the icing on the cake. Plant J 61: 1067–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulpice R, Trenkamp S, Steinfath M, Usadel B, Gibon Y, Witucka-Wall H, Pyl ET, Tschoep H, Steinhauser MC, Guenther M, et al. (2010) Network analysis of enzyme activities and metabolite levels and their relationship to biomass in a large panel of Arabidopsis accessions. Plant Cell 22: 2872–2893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TP, Gubler F. (2004) Molecular mechanism of gibberellin signaling in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 55: 197–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TP, Kamiya Y. (1997) Regulation and cellular localization of ent-kaurene synthesis. Physiol Plant 101: 701–708 [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Nakagawa S, Kamide Y, Kobayashi K, Ohyama K, Hashinokuchi H, Kiuchi R, Saito K, Muranaka T, Nagata N. (2009) Complete blockage of the mevalonate pathway results in male gametophyte lethality. J Exp Bot 60: 2055–2064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi M, Taniguchi Y, Kawasaki M, Takeda S, Kato T, Sato S, Tabata S, Miyake H, Sugiyama T. (2002) Identifying and characterizing plastidic 2-oxoglutarate/malate and dicarboxylate transporters in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 43: 706–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub DR, Miller B, Allen H. (2008) Effects of elevated CO2 on the protein concentration of food crops: a meta-analysis. Glob Change Bio 14: 565–575 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G, Tricker PJ, Zhang FZ, Alston VJ, Miglietta F, Kuzminsky E. (2003) Spatial and temporal effects of free-air CO2 enrichment (POPFACE) on leaf growth, cell expansion, and cell production in a closed canopy of poplar. Plant Physiol 131: 177–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng N, Wang J, Chen T, Wu X, Wang Y, Lin J. (2006) Elevated CO2 induces physiological, biochemical and structural changes in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 172: 92–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SG, Phillips AL, Hedden P. (1999) Molecular cloning and functional expression of gibberellin 2-oxidases, multifunctional enzymes involved in gibberellin deactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 4698–4703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Nakajima M, Motoyuki A, Matsuoka M. (2007) Gibberellin receptor and its role in gibberellin signaling in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 58: 183–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sandt VST, Suslov D, Verbelen JP, Vissenberg K. (2007) Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase activity loosens a plant cell wall. Ann Bot (Lond) 100: 1467–1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese A, Christ MM, Virnich O, Schurr U, Walter A. (2007) Spatio-temporal leaf growth patterns of Arabidopsis thaliana and evidence for sugar control of the diel leaf growth cycle. New Phytol 174: 752–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S. (2008) Gibberellin metabolism and its regulation. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59: 225–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zell MB, Fahnenstich H, Maier A, Saigo M, Voznesenskaya EV, Edwards GE, Andreo C, Schleifenbaum F, Zell C, Drincovich MF, et al. (2010) Analysis of Arabidopsis with highly reduced levels of malate and fumarate sheds light on the role of these organic acids as storage carbon molecules. Plant Physiol 152: 1251–1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Yu X, Foo E, Symons GM, Lopez J, Bendehakkalu KT, Xiang J, Weller JL, Liu X, Reid JB, et al. (2007) A study of gibberellin homeostasis and cryptochrome-mediated blue light inhibition of hypocotyl elongation. Plant Physiol 145: 106–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]