Abstract

Mucolipidosis II (ML II) or inclusion cell disease (I-cell disease) is a rarely occurring autosomal recessive lysosomal enzyme-targeting disease. This disease is usually found to occur in individuals aged between 6 and 12 months, with a clinical phenotype resembling that of Hurler syndrome and radiological findings resembling those of dysostosis multiplex. However, we encountered a rare case of an infant with ML II who presented with prenatal skeletal dysplasia and typical clinical features of severe secondary hyperparathyroidism at birth. A female infant was born at 37+1 weeks of gestation with a birth weight of 1,690 g (<3rd percentile). Prenatal ultrasonographic findings revealed intrauterine growth retardation and skeletal dysplasia. At birth, the patient had characteristic features of ML II, and skeletal radiographs revealed dysostosis multiplex, similar to rickets. In addition, the patient had high levels of alkaline phosphatase and parathyroid hormone, consistent with severe secondary neonatal hyperparathyroidism. The activities of β-D-hexosaminidase and α-N-acetylglucosaminidase were moderately decreased in the leukocytes but were 5- to 10-fold higher in the plasma. Examination of a placental biopsy specimen showed foamy vacuolar changes in trophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts. The diagnosis of ML II was confirmed via GNPTAB genetic testing, which revealed compound heterozygosity of c.3091C>T (p.Arg1031X) and c.3456_3459dupCAAC (p.Ile1154GlnfsX3), the latter being a novel mutation. The infant was treated with vitamin D supplements but expired because of asphyxia at the age of 2 months.

Keywords: Mucolipidosis, Newborn infant, Secondary hyperparathyroidism, Enzyme assays, Human GNPTAB protein

Introduction

Mucolipidosis II (ML II), which is also called inclusion cell disease (I-cell disease), is an autosomal recessive disorder due to deficiency of uridine diphosphate-N-acetylglucosamine: lysosomal enzyme N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphotransferase (GlcNAc-1-phosphotransfer-ase)1). This enzyme is involved in the first step of synthesis of the mannose 6-phosphate signal, which allows specific targeting of lysosomal acid hydrolase from the trans-Golgi network to lysosomes2-4). The lack of this enzyme precludes the generation of the common phosphomannosyl recognition marker of lysosomal enzymes1,5-10). Consequently, newly synthesized lysosomal enzymes are secreted into the extracellular space rather than targeted to the lysosomes. Thus, affected lysosomes are secondarily deficient in most acid hydrolases11) and are unable to degrade some macromolecules. In contrast, plasma levels of lysosomal hydrolases are high12). The resulting lysosomal storage, which was first reported in cultured fibroblasts13,14), is seen as cytoplasmic inclusion bodies, particularly in mesenchymal cells, hence the term I-cell disease12,15).

ML II was first recognized as a distinct entity in 1967 and was described as a Hurler-like disorder13). However, it has a more severe phenotype than that of Hurler disease with marked skeletal dysplasia, significant psychomotor retardation, and death within the first decade of life12,16). The diagnosis is established by detection of markedly elevated activities of lysosomal enzymes in the serum and/or low activities of lysosomal enzymes in fibroblasts. Characteristic inclusions can be observed in cultured fibroblasts under light microscopy17,18). This disease is caused by GlcNAc-phosphotransferase α/β-subunits precursor gene (GNPTAB) mutations19), which are associated with complete loss of GlcNAc-1-phosphotransferase activity20).

ML II usually presents between 6 and 12 months of age with a clinical phenotype resembling that of Hurler syndrome and a radiological picture of dysostosis multiplex18,21,22). However, we recently encountered a rare case of ML II in which the patient exhibited intrauterine skeletal abnormalities and typical clinical features with severe secondary hyperparathyroidism at birth.

Case report

1. Prenatal history

A 29-year-old woman visited the obstetrics clinic at Seoul National University Hospital for a prenatal screening ultrasound at 28+6 weeks of gestation. The mother reported no specific history of medication or illness except hypertension. Ultrasound findings indicated intrauterine growth retardation and skeletal dysplasia. Oligohydramnios was not present. Amniocentesis was conducted at 31+1 weeks. Chromosomal analysis revealed a 46, XX karyotype, and the result of the achondroplasia gene study was negative.

2. Present illness

A female infant was born at 37+1 weeks of gestation by vaginal delivery. At birth, she did not cry immediately, and her heart rate was less than 100 beats/min. Her respiratory condition improved after positive pressure ventilation for a few minutes, and she was transferred to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit without O2 supplementation soon thereafter. Apgar scores were 5 at 1 minute, 6 at 5 minutes, and 7 at 10 minutes after birth.

3. Physical examination

At birth, she was noted to be small for her gestational age with a birth weight of 1.69 kg (<3rd percentile); birth length, 45 cm (3rd to 10th percentile); and head circumference, 29 cm (<3rd percentile). She had coarse facial features, such as a flat midface, broad and depressed nasal bridge, long philtrum, prominent mouth, and gingival hypertrophy. The shallow orbits, thick skin, and full cheeks contributed to the appearance of deep infraorbital creases (Fig. 1). Skeletal abnormalities such as claw hands, short upper extremities, arthrogryposis of both wrists, contracture of both hip and knee joints, bowing of both tibiae, and clubfeet were observed (Fig. 2). In addition, she had thickened skin and thin, golden-colored hair.

Fig. 1.

Flat midface, broad and depressed nasal bridge, long philtrum, prominent mouth, and gingival hypertrophy are evident. The shallow orbits, thick skin, and full cheeks contribute to the appearance of deep infraorbital creases.

Fig. 2.

Skeletal abnormalities such as claw hands, short upper extremities, arthrogryposis of both wrists, contracture of both hip and knee joints, bowing of both tibiae, and clubfeet are evident.

4. Radiographic findings

The skeletal radiographs revealed dysostosis multiplex and were similar to findings in rickets. A skull radiograph revealed under-ossification of the calvarium, osteopenia of the mandible with loss of the lamina dura, and premature synostosis of the metopic suture (Fig. 3). Diffuse and severe osteopenia of the long bones; healed fractures at both distal radii, ulnae, proximal femurs, distal tibiae, distal fibulae, and proximal humeri; and stippling at the tali were found on the infantogram (Fig. 4). A wrist radiograph revealed diffuse osteopenia and diaphyseal cloaking at both humeri. In addition, the distal metaphyses of the forearm bones showed cupping, which is similar to the finding in rickets (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Skull radiographs showing underossification of the calvarium, osteopenia of the mandible with loss of the lamina dura, and premature synostosis of the metopic suture.

Fig. 4.

An infantogram showing diffuse and severe osteopenia of the long bones; healed fractures at both distal radii, ulnae, proximal femurs, distal tibiae, distal fibulae, and proximal humeri; and stippling at the tali.

Fig. 5.

A wrist radiograph showing diffuse osteopenia, diaphyseal cloaking at both humeri, and cupping in the distal metaphyses of the forearm bones.

5. Hospital course and laboratory findings

On the third day of life, total serum calcium (Ca) and phosphorus (P) were within the normal ranges (9.5 mg/dL and 5.8 mg/dL, respectively), but alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and parathyroid hormone (PTH) were markedly elevated (663 IU/L and 1,076.1 pg/mL, respectively). The serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) level was slightly low (5.5 mg/mL), while the 1,25-dihydroxyvitmin D (1,25D) level was normal (25.9 pg/mL). The urinary Ca/creatinine (Cr) ratio was 0.10 (reference range, 0.03 to 0.9), and the urinary P/Cr ratio was 1.25 (reference range, 0.39 to 5.6). The following serum parameters were normal in a maternal blood sample: total Ca (9.0 mg/dL), phosphate (4.1 mg/dL), ALP (125 IU/L), PTH (16 pg/mL), 25OHD (10.1 ng/mL), and 1,25D (11.0 pg/mL). A secundum atrial septal defect (2.8 mm), a small muscular ventricular septal defect (1.5 mm), and a patent ductus arteriosus (3.35 mm) were detected on an echocardiogram. Significant valve abnormalities were not found. Ophthalmologic examination did not reveal blue sclera or corneal clouding, but stromal hypoplasia of both irises was discovered.

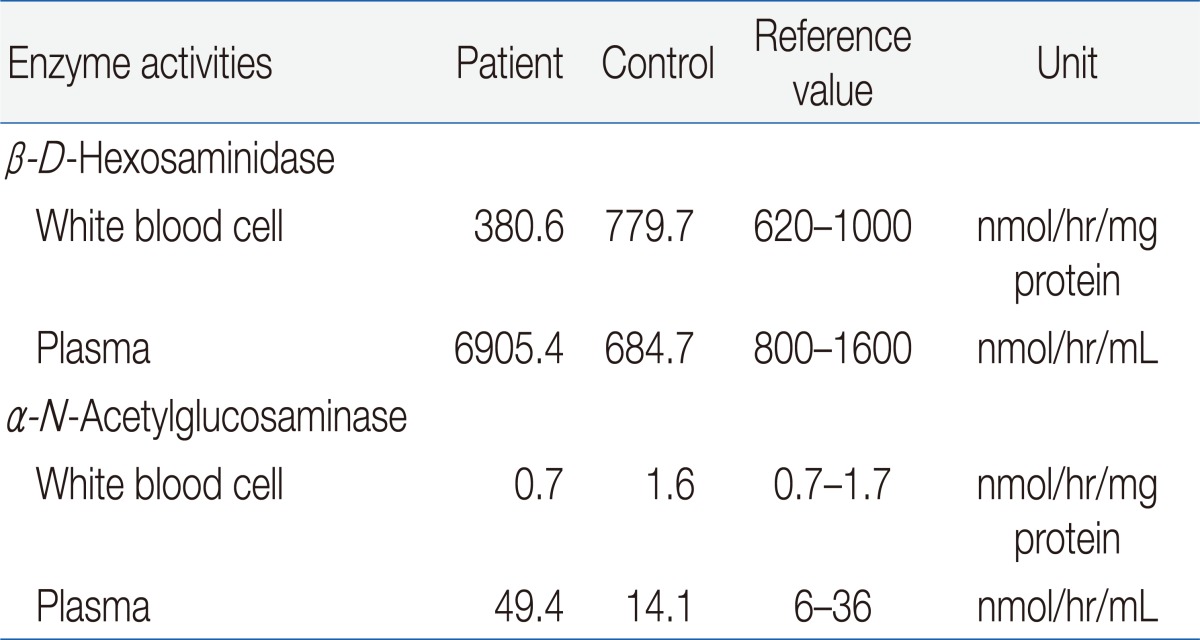

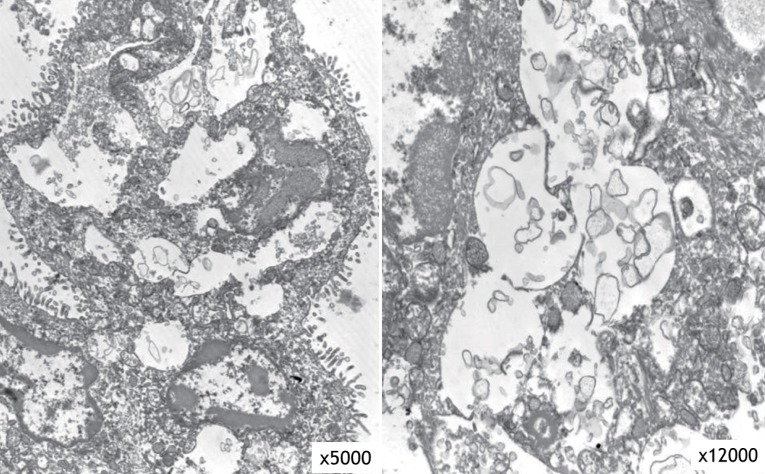

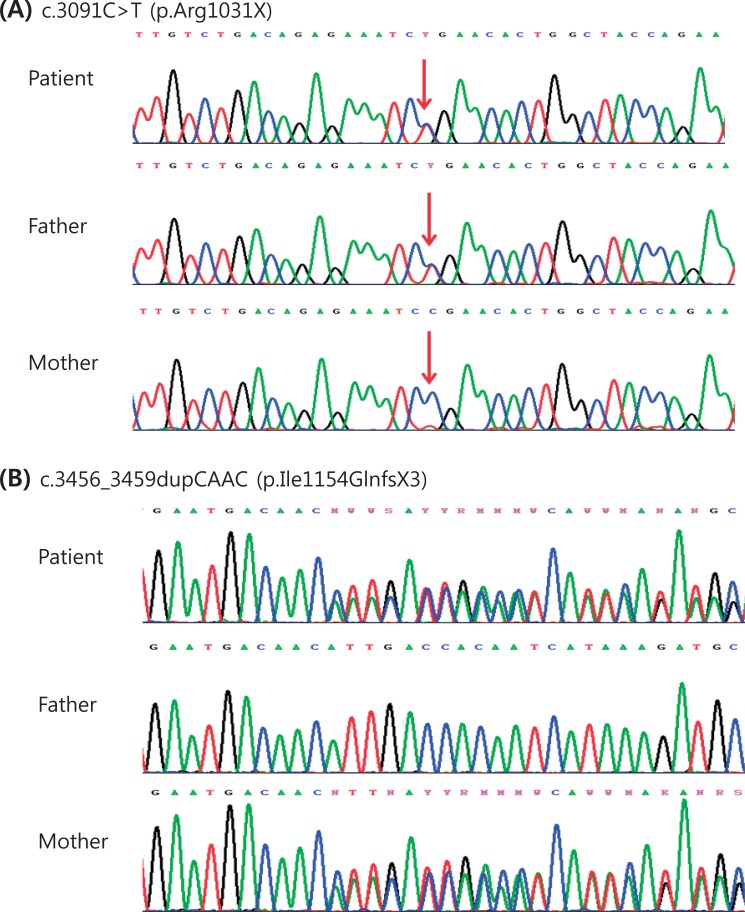

The result of a urine mucopolysaccharidosis screening test was negative. The activities of β-D-hexosaminidase and α-N-acetylglucosaminidase were moderately decreased in leukocytes but were 5- to 10-fold higher than that of the control in plasma (Table 1). Examination of a placental biopsy specimen showed foamy vacuolar changes in trophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts (Fig. 6). Diagnosis of ML II was confirmed by GNPTAB genetic testing, which revealed compound heterozygosity of c.3091C>T (p.Arg1031X) and c.3456_3459dupCA AC(p.Ile1154GlnfsX3) (Fig. 7).

Table 1.

Lysosomal Enzyme Activities

Fig. 6.

Electron microscopy of the placental biopsy specimen revealed foamy vacuolar changes in trophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts.

Fig. 7.

The GNPTAB genetic testing revealed compound heterozygosity of c.3091C>T (p.Arg1031X) (A) and c.3456_3459dupCAAC (p.Ile1154GlnfsX3) (B). The c.3091C>T mutation was inherited from the father, and the c.3456_3459dupCAAC mutation was inherited from the mother.

During admission, the ductus arteriosus was closed by the use of oral ibuprofen. Enteral tube feeding was started on the seventh day of life because her sucking power was decreased and oral feeding was impossible. Nasal flaring, subcostal retraction, and mild desaturation (SpO2, 90 to 95% at room air) began on the eighth day of life, and the respiratory viral study revealed positivity for human coronavirus OC43/HKU1. Fortunately, this respiratory difficulty was not aggravated, and the patient recovered spontaneously within a few days.

The patient was treated with vitamin D supplements (0.125 mcg alfacalcidol, once daily) from the fifth day of life. However, the alfacalcidol dose was raised to 0.25 mcg once daily when the ALP level further increased to 1,071 IU/L on the 12th day of life. She was discharged at 22nd day of age. At that time, her weight was 1.92 kg (<3rd percentile); length, 45 cm (<3rd percentile); and head circumference, 31 cm (<3rd percentile). She did not require supplemental oxygen or gastric tube feeding. After discharge, her ALP level increased to 2,562 IU/L on the 40th day of life, so the alfacalcidol dose was raised to 0.375 mcg once daily. Although the patient appeared to be well, she died from asphyxia at 2 months of age.

Discussion

ML II is an autosomal recessive lysosomal enzyme-targeting disease. Although the true prevalence of ML II is unknown, the disease appears to be rare. Its prevalence has been estimated at 1/123,500 live births in Portugal23), 1/252,500 in Japan16), and 1/625,500 in the Netherlands24). In Korea, there are very few reports of mucolipidosis25-27). There were 3 cases of ML II, 3 cases of ML III, and 1 case of ML that was not classified. All cases of ML II were diagnosed after one year of age (1.4 to 2.3 years) and they had typical characteristics of ML II, such as growth retardation, developmental delay, and severe skeletal deformity. Unlike these cases, our case exhibited skeletal dysplasia and intrauterine growth retardation before 30 weeks of gestation. The characteristic clinical phenotype, the radiological feature of dysostosis multiplex resembling rickets, and severe osteopenia were present at birth. Our patient was diagnosed with ML II during the neonatal period. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of ML II that manifested during the prenatal period and diagnosed neonatally in Korea.

Several reports have described cases of ML II that expressed skeletal dysplasia prenatally28,29). In Lachman's study29), the most common disorders associated with fetal skeletal dysplasia were osteogenesis imperfect (18%), thanatophoric dysplasia (14%), campomelic dysplasia (6%), and achondrogenesis type II (5%). In that report, 8 patients were diagnosed with ML II. Their sonographic findings showed short long bones, and 4 cases were detected during the second trimester. In the present case, prenatal ultrasonographic findings included rhizomelia in the upper extremities and micromelia in the lower extremities.

Our patient exhibited severe skeletal changes from multiple fractures, diffuse diaphyseal cloaking in the long bones, marked osteopenia, underossification of the calvarium, and resorption of the mandible with loss of the lamina dura. The distal metaphyses of long tubular bones showed irregular demineralization, which is seen in rickets. These signs suggest the presence of hyperparathyroidism, which was confirmed by the high levels of ALP and PTH. However, in contrast to neonatal severe primary hyperparathyroidism, her total Ca level was normal. These observations are consistent with severe secondary neonatal hyperparathyroidism. The etiology of severe secondary hyperparathyroidism in fetuses and newborns with ML II is uncertain. However, it is speculated that the enzyme-targeting defect in ML II involves trophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts in the placenta; this interferes with transplacental Ca transport and leads to Ca starvation of the fetus and activation of the parathyroid response to maintain extracellular Ca18). This hypothesis is supported by the findings of foamy vacuolar changes in trophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts in the present case.

GNPTAB, which is the only gene known to be associated with ML II, was first identified by Tiede et al.30) in 2005. ML II correlates with an almost total absence of phosphotransferase activity resulting from homozygosity or compound heterozygosity due to frameshift or nonsense mutations in the GNPTAB gene. However, the presence of at least 1 hypomorph (a missense or splicing site mutation) allele in the GNPTAB mutant genotype results in a clinically milder form of ML III alpha/beta with a low level of phosphotransferase activity3). The same result was reported in a Korean study26). We performed a genetic study by direct sequencing of all coding exons and flanking intronic regions of GNPTAB. We identified compound heterozygosity in the GNPTAB gene: a combination of a nonsense mutation (c.3091C>T [p.Arg1031X]) and a frameshift by a small insertion or duplication (c.3456_3459dupCAAC [p.Ile1154GlnfsX3]). We confirmed the diagnosis as ML II because the hypomorph allele was not present. The nonsense mutation was inherited from the father, and the frameshift mutation was inherited from the mother. The c.3091C>T mutation has been noted in the literature3), but the c.3456_3459dupCAAC mutation is novel.

In conclusion, severe cases of ML II can present earlier as prenatal skeletal dysplasia and neonatal severe secondary hyperparathyroidism, as in the present case. Therefore, ML II must be considered if the patient presents with intrauterine skeletal dysplasia or severe osteopenia and rickets-like radiologic features at birth, and a prompt evaluation should be conducted.

References

- 1.Hasilik A, Waheed A, von Figura K. Enzymatic phosphorylation of lysosomal enzymes in the presence of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine. Absence of the activity in I-cell fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;98:761–767. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pohl S, Marschner K, Storch S, Braulke T. Glycosylation- and phosphorylation-dependent intracellular transport of lysosomal hydrolases. Biol Chem. 2009;390:521–527. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cathey SS, Leroy JG, Wood T, Eaves K, Simensen RJ, Kudo M, et al. Phenotype and genotype in mucolipidoses II and III alpha/beta: a study of 61 probands. J Med Genet. 2010;47:38–48. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.067736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kollmann K, Pohl S, Marschner K, Encarnacao M, Sakwa I, Tiede S, et al. Mannose phosphorylation in health and disease. Eur J Cell Biol. 2010;89:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hickman S, Neufeld EF. A hypothesis for I-cell disease: defective hydrolases that do not enter lysosomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;49:992–999. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(72)90310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Natowicz MR, Chi MM, Lowry OH, Sly WS. Enzymatic identification of mannose 6-phosphate on the recognition marker for receptor-mediated pinocytosis of beta-glucuronidase by human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:4322–4326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bach G, Bargal R, Cantz M. I-cell disease: deficiency of extracellular hydrolase phosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;91:976–981. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)91975-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasilik A, Klein U, Waheed A, Strecker G, von Figura K. Phosphorylated oligosaccharides in lysosomal enzymes: identification of alpha-N-acetylglucosamine(1)phospho(6)mannose diester groups. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:7074–7078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varki A, Kornfeld S. Structural studies of phosphorylated high mannose-type oligosaccharides. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:10847–10858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reitman ML, Kornfeld S. UDP-N-acetylglucosamine:glycoprotein N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphotransferase. Proposed enzyme for the phosphorylation of the high mannose oligosaccharide units of lysosomal enzymes. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:4275–4281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lightbody J, Wiesmann U, Hadorn B, Herschkowitz N. I-cell disease: multiple lysosomal-enzyme defect. Lancet. 1971;1:451. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leroy JG, Spranger JW, Feingold M, Opitz JM, Crocker AC. I-cell disease: a clinical picture. J Pediatr. 1971;79:360–365. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(71)80142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leroy JG, Demars RI. Mutant enzymatic and cytological phenotypes in cultured human fibroblasts. Science. 1967;157:804–806. doi: 10.1126/science.157.3790.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanai J, Leroy J, O'Brien JS. Ultrastructure of cultured fibroblasts in I-cell disease. Am J Dis Child. 1971;122:34–38. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1971.02110010070011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tondeur M, Vamos-Hurwitz E, Mockel-Pohl S, Dereume JP, Cremer N, Loeb H. Clinical, biochemical, and ultrastructural studies in a case of chondrodystrophy presenting the I-cell phenotype in tissue culture. J Pediatr. 1971;79:366–378. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(71)80143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okada S, Owada M, Sakiyama T, Yutaka T, Ogawa M. I-cell disease: clinical studies of 21 Japanese cases. Clin Genet. 1985;28:207–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1985.tb00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varki A, Reitman ML, Vannier A, Kornfeld S, Grubb JH, Sly WS. Demonstration of the heterozygous state for I-cell disease and pseudo-Hurler polydystrophy by assay of N-acetylglucosaminylphosphotransferase in white blood cells and fibroblasts. Am J Hum Genet. 1982;34:717–729. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unger S, Paul DA, Nino MC, McKay CP, Miller S, Sochett E, et al. Mucolipidosis II presenting as severe neonatal hyperparathyroidism. Eur J Pediatr. 2005;164:236–243. doi: 10.1007/s00431-004-1591-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kudo M, Brem MS, Canfield WM. Mucolipidosis II (I-cell disease) and mucolipidosis IIIA (classical pseudo-hurler polydystrophy) are caused by mutations in the GlcNAc-phosphotransferase alpha / beta -subunits precursor gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:451–463. doi: 10.1086/500849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muller-Loennies S, Galliciotti G, Kollmann K, Glatzel M, Braulke T. A novel single-chain antibody fragment for detection of mannose 6-phosphate-containing proteins: application in mucolipidosis type II patients and mice. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:240–247. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taber P, Gyepes MT, Philippart M, Ling S. Roentgenographic manifestations of Leroy's I-cell disease. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;118:213–221. doi: 10.2214/ajr.118.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patriquin HB, Kaplan P, Kind HP, Giedion A. Neonatal mucolipidosis II (I-cell disease): clinical and radiologic features in three cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1977;129:37–43. doi: 10.2214/ajr.129.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinto R, Caseiro C, Lemos M, Lopes L, Fontes A, Ribeiro H, et al. Prevalence of lysosomal storage diseases in Portugal. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:87–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poorthuis BJ, Wevers RA, Kleijer WJ, Groener JE, de Jong JG, van Weely S, et al. The frequency of lysosomal storage diseases in The Netherlands. Hum Genet. 1999;105:151–156. doi: 10.1007/s004399900075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee HJ. Inborn errors of metabolism in Korea. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2004;22:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paik KH, Song SM, Ki CS, Yu HW, Kim JS, Min KH, et al. Identification of mutations in the GNPTA (MGC4170) gene coding for GlcNAc-phosphotransferase alpha/beta subunits in Korean patients with mucolipidosis type II or type IIIA. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:308–314. doi: 10.1002/humu.20205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song J, Lee DS, Cho HI, Kim JQ, Cho TJ. Biochemical characteristics of a Korean patient with mucolipidosis III (pseudo-Hurler polydystrophy) J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18:722–726. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.5.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saul RA, Proud V, Taylor HA, Leroy JG, Spranger J. Prenatal mucolipidosis type II (I-cell disease) can present as Pacman dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;135:328–332. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lachman RS. Fetal imaging in the skeletal dysplasias: overview and experience. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24:413–417. doi: 10.1007/BF02011907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tiede S, Storch S, Lubke T, Henrissat B, Bargal R, Raas-Rothschild A, et al. Mucolipidosis II is caused by mutations in GNPTA encoding the alpha/beta GlcNAc-1-phosphotransferase. Nat Med. 2005;11:1109–1112. doi: 10.1038/nm1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]