Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) derived from endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is a potent vasodilator and signaling molecule that plays essential roles in neovascularization. During limb ischemia, decreased NO bioavailability occurs secondary to increased oxidant stress, decreased l-arginine and tetrahydrobiopterin. This study tested the hypothesis that dietary cosupplementation with tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), l-arginine and vitamin C acts synergistically to decrease oxidant stress, increase NO and thereby increase blood flow recovery after hindlimb ischemia. Rats were fed normal chow, chow supplemented with BH4 or l-arginine (alone or in combination) or chow supplemented with BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C for 1 wk before induction of hindlimb ischemia. In the is-chemic hindlimb, cosupplementation with BH4 + l-arginine resulted in greater eNOS and phospho-eNOS (P-eNOS) expression, Ca2+-dependent NOS activity and NO concentration in the ischemic calf region (gastrocnemius), as well as greater NO concentration in the region of collateral arteries (gracilis). Rats receiving cosupplementation of BH4 + l-arginine led to greater recovery of foot perfusion and greater collateral enlargement than did rats receiving either agent separately. The addition of vitamin C to the BH4 + l-arginine regimen further increased these dependent variables. In addition, rats given all three supplements showed significantly less Ca2+-independent activity, less nitrotyrosine accumulation, greater glutathione (GSH)–to–glutathione disulfide (GSSG) ratio and less gastrocnemius muscle necrosis, on both macroscopic and microscopic levels. In conclusion, co-supplementation with BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C significantly increased blood flow recovery after hindlimb ischemia by reducing oxidant stress, increasing NO bioavailability, enlarging collateral arteries and reducing muscle necrosis. Oral cosupplementation of BH4, l-arginine and vitamin C holds promise as a biological therapy to induce collateral artery enlargement.

INTRODUCTION

Endothelial dysfunction is a hallmark of peripheral artery disease (PAD) (1). Central to the development of endothelial dysfunction, regardless of its cause, is a reduction in the bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO) derived from endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). Three fundamental mechanisms can compromise NO bioavailability: loss of eNOS expression, loss of eNOS-derived NO production (that is, functional inactivation of eNOS) and inactivation of NO by superoxide anion (O2−) to form peroxynitrite (OONO−) (2,3). It is likely that all three mechanisms contribute to the endothelial dysfunction characteristic of PAD because increased oxidant stress is a common antecedent in the pathogenesis of this disease and can reduce NO bioavailability.

At least two characteristics of eNOS render it susceptible to oxidant stress. First, eNOS transcription, posttranslational modification and trafficking to the caveolae are attenuated by the accumulation of reactive oxygen species within the endothelial cell (4). Second, the eNOS cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) is highly susceptible to oxidation (5). BH4 maintains eNOS in its functional dimeric form; in the absence of BH4, eNOS becomes uncoupled so that the electron flux is diverted away from the l-arginine binding site and instead reduces molecular oxygen, generating O2−(6). This circumstance initiates a vicious cycle, wherein eNOS catalytic activity produces O2−, not NO, worsening existent oxidant stress.

These molecular characteristics of eNOS predict that several therapeutic options might prove effective for the treatment of PAD, namely dietary supplementation with an antioxidant, or with the eNOS substrate l-arginine, or with the eNOS cofactor BH4. Vitamin C, or l-ascorbic acid, is a potent antioxidant and has been shown to preserve BH4 levels and enhance endothelial NO production in vitro(7). ONOO− reacts with BH4 6–10 times faster when in the presence of ascorbate. The intermediate product of the reaction between ONOO− and BH4 is the trihydrobiopterin radical (BH3−), which is then reduced back to BH4 by ascorbate. Thus, ascorbate does not protect BH4 from oxidation but rather recycles the BH3 radical back to BH4 (8). Vitamin C levels are low in PAD patients (9), and acute (10) or short-term (11) vitamin C supplementation reduces PAD symptoms; however, cross-sectional epidemiological surveys have failed to find a clear link between long-term vitamin C intake and PAD symptoms or disease progression (12,13). l-Arginine supplementation showed exciting promise in short-term studies of PAD (14,15), but this effect was not observed in a subsequent long-term study by the same group (16). BH4 improves eNOS-dependent vasodilation in long-term smokers and patients with type 2 diabetes, conditions associated with increased oxidant stress (17,18). To our knowledge, BH4 has not been specifically evaluated as a therapeutic modality in PAD.

An important gap in our understanding of BH4, l-arginine and l-ascorbic acid in the prevention and treatment of PAD is the potential synergistic effect of combined therapy, and there is convincing evidence to suggest that such an approach would prove successful. For example, supplementation with l-arginine alone might prove deleterious in the face of endothelial oxidant stress inasmuch as the resultant increase in eNOS catalytic activity might generate O2−, not NO, if BH4 levels were reduced by oxidation. Thus, cosupplementation of l-arginine with l-ascorbic acid and BH4 might enhance the therapeutic outcome by reducing oxidant stress and preserving eNOS in its functional dimeric form, respectively. This action would enhance eNOS-derived NO production and, by quenching existent O2−, reduce NO inactivation by its reaction with O2−.

In our previous work (19), we observed decreased eNOS expression, decreased bioavailable NO and increased oxidant stress in rats that had hindlimb ischemia, and oral supplementation of BH4 increased the beneficial effect of eNOS gene transfer. The goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that combined dietary supplementation with BH4, l-arginine and vitamin C act synergistically to improve hindlimb blood flow recovery and preservation of muscle viability in response to severe hindlimb ischemia. To this end, we generated severe hindlimb ischemia in the rat by means of femoral artery excision. Measured dependent variables included calf and thigh muscle NO bioavailability, hindlimb laser Doppler perfusion and collateral artery enlargement, and calf and thigh muscle oxidative stress and tissue necrosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Dietary supplements included BH4 (10 mg/kg/d; Schircks Laboratories, Jonas, Switzerland); l-arginine, provided as l-arginine α-ketoglutarate (hereafter, l-arginine; 88.5 mg/kg/d; Body Tech, North Bergen, NJ, USA); and l-ascorbic acid (that is, vitamin C; 88.5 mg/kg/d; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The dose of tetrahydrobiopterin was selected on the basis of a published report of its use in rats (20). And the dose of l-arginine and vitamin C was based on their clinical dose in patients.

Animals

All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, San Francisco, and the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Adult male Sprague Dawley rats weighing 265–285 g (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) were maintained in a clean housing facility on a 12-h light–dark cycle.

Preparation

Severe ischemia was induced in the left hindlimb. The femoral artery was ligated between the inguinal ligament and popliteal fossa, and the ligated section and its branches were excised. This procedure was carried out under anesthesia with 2% isofluorane. The untreated right hindlimb served as an internal control for each rat. An additional group of sham-operated rats were also used for selected assays. These rats underwent isolation of the femoral artery in the left hindlimb under 2% isofluorane anesthesia, but the artery was left intact.

Study Design

All rats were fed standard chow in powder form and water ad libitum (Deans Feeds, Redwood City, CA, USA). Animals were randomly selected to receive normal chow (control), chow with a single added supplement (BH4 or l-arginine), chow supplemented with BH4 + l-arginine or chow supplemented with BH4 + l-arginine + l-ascorbic acid. Dietary supplementation was commenced 7 d before the induction of hindlimb ischemia and was continued until sacrifice of the animal. Chow was replaced every 2 d. The time of sacrifice varied with the measured end point under consideration, as described below.

Western Blotting

Rats were sacrificed 14 d after induction of ischemia for measurement of gastrocnemius and gracilis muscles of eNOS, phospho-eNOS (P-eNOS) and nitrotyrosine expression. The timing of sacrifice was selected on the basis of previous work that demonstrated maximal postischemic change in these variables at this time (19). Samples were homogenized in liquid nitrogen and transferred to NP-40 lysis buffer, comprised of 50 mmol/L N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (pH 7.5), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L ethylene-diaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 100 mmol/L NaF, 1% NP 40, 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 1 g/mL aprotinin. The lysates were centrifuged, the supernatant recovered and the protein concentration determined (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). Protein (100 μg) per sample was separated on a 7.5% or 12% sodium do-decyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel for determination of eNOS or nitrotyrosine, respectively, and then electroblotted on nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Her-cules, CA, USA). Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal anti-nitrotyrosine (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; 1:1,000), mouse monoclonal anti-eNOS (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA; 1:1,000) or rabbit anti-P-eNOS (cell signaling) and then incubated for 2 h with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-mouse or rabbit IgG antibody (Pierce Biotechnology; 1:5,000). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA). Band density was quantitated by standard densitometry and the intensity of the band of interest expressed as a function of the α-tubulin band.

eNOS Activity

Rats were sacrificed 14 d after induction of ischemia for determination of gastrocnemius muscle NOS activity by using an NOS activity assay kit (Cayman Chemical). This kit was based on the biochemical conversion of l-arginine to l-citrulline by NOS. Radioactive substrate [14C]arginine enables sensitivity to the picomole level as well as the specificity. Neutrally charged citrulline can be easily separated from positively charged arginine. The timing of sacrifice was selected on the basis of previous work that demonstrated maximal postischemic change in this variable at this time (19). Muscles were homogenized in ice-cold buffer [250 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mmol/L EDTA, 10 mmol/L ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA)] and centrifuged, and the protein in the supernatant was adjusted to 5 μg/mL. Samples were incubated in 10 mmol/L nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), 1 μCi/μL [14C]arginine, 6 mmol/L CaCl2, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 6 μmol/L BH4, 2 μmol/L flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and 2 μmol/L flavin mononucleotide (FMN) for 30 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped with 400 μL of 50 mmol/L HEPES, pH 5.5, and 5 mmol/L EDTA. Identical samples were prepared without CaCl2, and all reactions were performed in duplicate. The radioactivity of the sample eluate was measured and expressed as counts per minute (CPM)/μg protein. The Ca2+- dependent NOS activity, which corresponds to the sum of the endothelial and neural NOS isoforms, was calculated by subtracting the NOS activity measured in the absence of CaCl2 from the NOS activity measured in the presence of CaCl2. The Ca 2+-independent NOS activity corresponds to the inflammatory isoform of NOS (iNOS).

NOx (Nitrite + Nitrate) Assay

The left gastrocnemius and gracilis muscles after ischemic d 14 were collected and homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After centrifugation, ultrafilter tissue homogenates were put through a 10-kDa molecular weight cutoff filter. Filtrate was used for nitrite and nitrate concentration measurement according to the protocol of a Nitrate/Nitrite Fluorometric Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical).

Assay of GSH-to-GSSG Ratio

The left gastrocnemius and gracilis muscles were homogenized and deproteinated. And then the supernatant was used for the measurement of glutathione disulfide (GSSG) and glutathione (GSH) according to the Glutathione Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical).

Hindlimb Perfusion

Hindlimb blood flow was determined by means of laser Doppler imaging (Moor Instruments, Devon, UK). Flow was measured preoperatively, immediately after arterial excision, and then 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35 and 42 d after induction of ischemia. Scans were obtained during inhalation of 1% isofluorane while core body temperature was maintained between 36.8 and 37.2°C. Scans were repeated three times, and the average for each rat was determined. Data were expressed as the ratio of ischemic to nonischemic hindlimb.

Angiograms

Angiograms were performed 42 d after induction of ischemia. Barium sulfate (2.5 mL; EZPaqe, Merry X-Ray, South San Francisco, CA, USA) was infused into the infrarenal aorta after ligation of the proximal aorta and inferior vena cava during inhalation of 2% isofluorane. A grid was superimposed over the film between the greater trochanter of the femur to the patella. The number of intersections between contrast-filled vessels and gridlines was determined independently by three blinded observers. The angioscore was calculated as the average ratio of intersections to the total number of gridlines. Within the experimental setting of this study, the angioscore is a marker of collateral artery enlargement; thus, as collateral arteries dilate and remodel in response to femoral artery excision, their diameters increase, enhancing their visibility on the X-ray film and thus increasing the angioscore (19).

Collateral Diameter

The gracilis muscles were harvested on d 42 after induction of ischemia. Collateral arteries were identified by double staining in 10-μm cryosections with antibodies for CD31 (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1, a marker of endothelial cells from BD-Biosciences) and smooth muscle actin (Sigma-Aldrich). Collateral artery diameter was measured in 10 randomly selected low-power fields by using precalibrated microscope calipers (Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany), and the average diameter was determined for each rat. All measurements were made in a blinded manner.

Nitroblue Tetrazolium Staining to Detect Muscle Necrosis

The left gastrocnemius muscle was removed 7 d after induction of ischemia. The timing of sacrifice was selected on the basis of previous work that demonstrated maximal postischemic muscle necrosis at this time (19). The muscle was cut transversely into three 2-mm sections. Two sections were used for nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) staining, whereas the third was frozen (−80°C) in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) embedding compound. Sections for NBT staining were incubated in PBS containing 0.033% NBT (Fisher Biotech, Austin, TX, USA) and 0.133% NADH (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 21°C for 10 min. The samples were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h. The areas of viable tissue, indicated by dark blue color, and nonviable tissue, indicated by white color, were measured by quantitative image analysis (ImagePro, Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA). Data were expressed as the ratio of nonviable tissue to total tissue area. Measurements were made on the four exposed cut surfaces, and the average was taken and used as a single data point for each animal. The frozen section was used to prepare cryosections (10 μm) for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining to evaluate histological integrity of the muscle, as well as detect the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were carried out by means of analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls tests were carried out if the ANOVA F statistic was significant to determine sites of difference within the ANOVA format. Probability values <0.05 were accepted as significant for all statistical calculations.

RESULTS

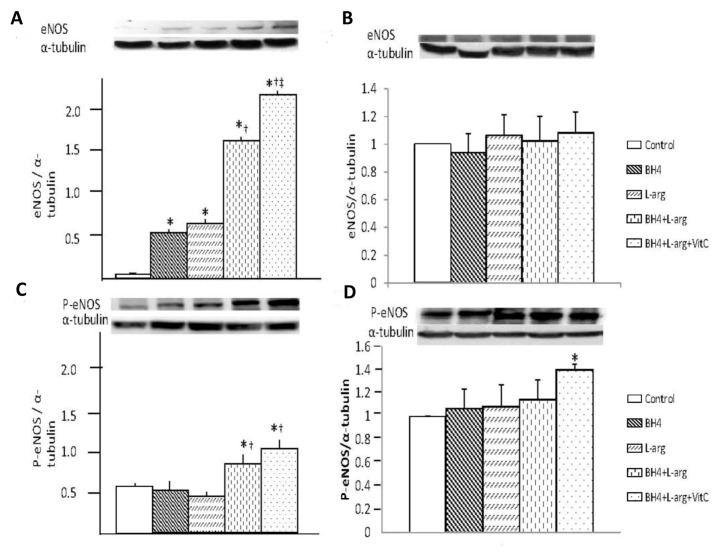

Effects of Oral BH4, l-Arginine and Vitamin C on Calf and Thigh Muscle eNOS and P-eNOS Expression

Dietary supplementation of BH4, l-arginine and vitamin C significantly affected eNOS and P-eNOS expression in the ischemic calf region, as measured in the gastrocnemius muscle (Figures 1A, C). Rats given single supplementation with BH4 or l-arginine showed similar levels of eNOS expression, and these levels were significantly greater than that of rats fed normal chow. Rats given two (BH4 + l-arginine) or three (BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C) supplements also had greater levels of eNOS expression than those in rats given single supplements. Hence, the combination of BH4 and l-arginine had an additive effect on eNOS expression, and the addition of vitamin C provided an additional beneficial effect. Although, increased P-eNOS expression was only observed in rats fed BH4 + l-arginine and BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C. However, in the ischemic thigh region, dietary supplementation with BH4, l-arginine and vitamin C, singly or combined, had no effects on eNOS expression, but P-eNOS expression was increased significantly only when all three reagents (BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C) were administered simultaneously (Figures 1B, D).

Figure 1.

Effects of BH4, l-arginine (L-arg) and vitamin C (VitC) on eNOS and P-eNOS expression in the ischemic gastrocnemius muscle. Muscle was harvested 14 d after the induction of hindlimb ischemia and supernatants from muscle homogenates were used in these assays. (A) Expression of eNOS in gastrocnemius was increased by all dietary additives, although the greatest increase was noted in rats that received BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C. (B) Expression of eNOS in gracilis was not changed by any diet supplementation. (C) Expression of P-eNOS was increased in rats fed BH4 + l-arginine or BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C. (D) Expression of P-eNOS was significantly increased in rats fed BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C. Control rats were fed a standard diet, whereas the four treatment groups consumed diets supplemented with additives noted in the bar graph. Concentrations of these additives are noted in the text. Data are means ± standard deviation (sd); n = 5–6. *p < 0.05 versus control; †p < 0.05 versus BH4 or l-arginine groups; ‡p < 0.05 versus BH4 + l-arginine group.

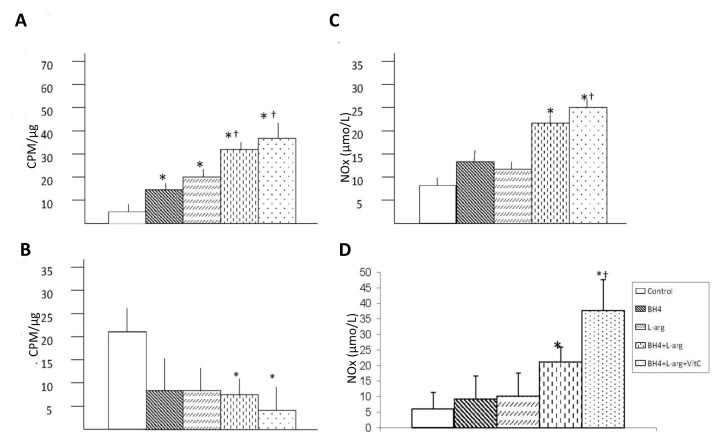

Effects of Oral BH4, l-Arginine and Vitamin C on Gastrocnemius Ca2+-Dependent NOS Activity

Dietary supplements affected Ca2+-dependent NOS activity in the ischemic gastrocnemius muscle (Figure 2A). Rats given a single dietary supplement (BH4 or l-arginine) demonstrated Ca2+-dependent NOS activities that were similar to each other and greater than that of rats fed normal chow. Rats given two (BH4 + l-arginine) or three (BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C) supplements displayed significantly greater Ca2+-dependent NOS activity than rats given a single dietary supplement. The combination of BH4 and l-arginine generated an additive effect. The addition of vitamin C further increased Ca2+-dependent NOS activity, although it did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Effects of BH4, l-arginine (L-arg) and vitamin C (VitC) on bioavailable NO in the ischemic gastrocnemius and gracilis muscles. Muscle was harvested 14 d after the induction of hindlimb ischemia, and supernatants from muscle homogenates were used in these assays. (A) Ca2+-dependent NOS activity was increased by all dietary additives, although the greatest increase was noted in mice receiving BH4 + l-arginine or BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C. Data are means ± sd; n = 5–6. *p < 0.05 versus control; †p < 0.05 versus BH4 or l-arginine groups. (B) Ca2+-independent NOS activity was less in mice receiving BH4 + l-arginine or BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C than in control mice. Data are means ± sd; n = 5–6. *p < 0.05 versus control. (C, D) NOx was increased in gastrocemius (C) and gracilis (D) in mice receiving BH4 + l-arginine or BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C. Data are means ± sd; n = 5. *p < 0.05 versus control; †p < 0.05 versus BH4 or l-arginine group. In all graphs, control rats were fed normal chow and underwent hindlimb ischemia, whereas the four treatment groups consumed diets supplemented with additives noted in the bar graph. Concentrations of these additives are noted in the text.

Effects of Oral BH4, l-Arginine and Vitamin C on Gastrocnemius Ca2+-Independent NOS Activity

Ca2+-independent NOS activity was greater in the ischemic gastrocnemius from rats fed normal chow than in the is-chemic gastrocnemius of dietary fed rats (Figure 2B). Rats fed the two dietary supplements (BH4 + l-arginine) or three dietary supplements (BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C) demonstrated Ca2+-independent NOS activity levels in the ischemic gastrocnemius muscle that were lower than in rats fed normal chow.

Effects of Oral BH4, l-Arginine and Vitamin C on Calf and Thigh Muscle NOx Levels

The final products of NO in vivo is nitrite (NO2−) and nitrate (NO3−). NOx is the sum of NO2− and NO3− and it is the best index of total NO production. The NOx concentration in the ischemic calf region (gastrocnemius) and collateral artery region (gracilis) was significantly higher than in rats fed with BH4 and l-arginine or BH4, l-arginine and vitamin C (Figures 2C, D). No changes occurred in rats fed with either agent alone. The addition of vitamin C further increased NOx levels, although it did not reach statistical significance.

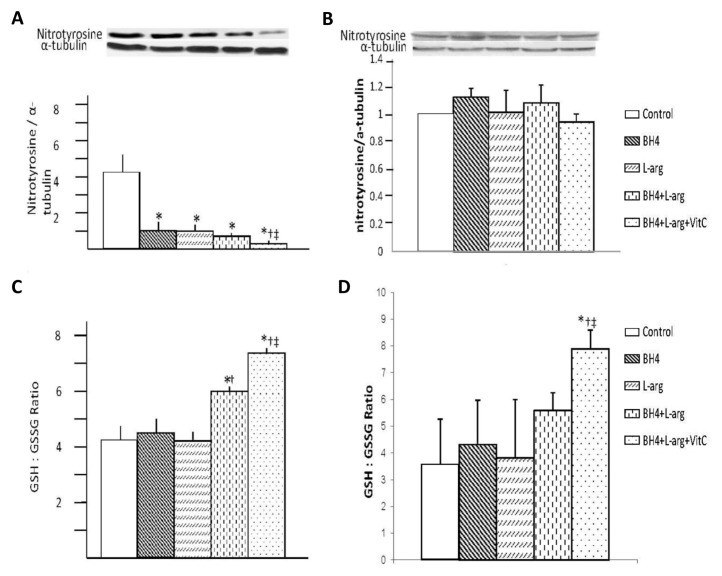

Effects of Oral BH4, l-Arginine and Vitamin C on Calf and Thigh Muscle Oxidant Stress

Dietary supplementation affected nitrotyrosine accumulation and the ratio of GSH versus GSSG in the ischemic calf region (gastrocnemius) and collateral artery region (gracilis) (Figure 3). Rats given a single dietary supplement (BH4 or l-arginine) or the combination of these dietary agents displayed similar nitrotyrosine levels in the ischemic calf region (gastrocnemius) (Figures 3A, C). These levels were significantly less than the level noted in rats fed normal chow. Rats provided with all three dietary supplements (BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C) exhibited a nitrotyrosine level significantly less than rats given a single supplement (BH4 or l-arginine) or the combination of these two agents. The ratio of reduced versus oxidized glutathione (GSH-to-GSSG) was also measured as another index of oxidant stress in the ischemic calf region (gastrocnemius). GSH-to-GSSG ratio was increased in the ischemic calf region of rats fed two dietary combinations (BH4 + l-arginine) or three dietary combinations (BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C). Addition of vitamin C had a beneficial effect in increasing GSH-to-GSSG ratio. However, in the collateral artery region (gracilis) (Figures 3B, D), none of the dietary supplementation regimens affected nitrotyrosine accumulation, but in rats fed a triple dietary combination (BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C), the GSH-to-GSSG ratio was increased significantly. Taken together, three dietary supplements given in combination (BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C) are more effective in decreasing ischemic muscle oxidant stress after induction of hindlimb ischemia in rats.

Figure 3.

Effects of BH4, l-arginine (L-arg) and vitamin C (VitC) on oxidative stress in the ischemic gastrocnemius and gracilis muscles. Muscle was harvested 14 d after the induction of hindlimb ischemia and supernatants from muscle homogenates were used in these assays. (A, B) Nitrotyrosine expression was decreased by all dietary additives, although this decrease was greatest in rats receiving BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C in ischemic gastrocnemius muscles (A), but no change was observed in ischemic gracilis muscles (B). (C, D) The GSH-to-GSSG ratio was increased in ischemic gastrocnemius (C) and gracilis (D) in rats receiving BH4 + l-arginine; the addition of vitamin C to this regimen caused an additional increase in this ratio. Data are means ± sd; n = 5–6. *p < 0.05 versus control; †p < 0.05 versus BH4 or l-arginine groups; ‡p < 0.05 versus BH4 + l-arginine groups.

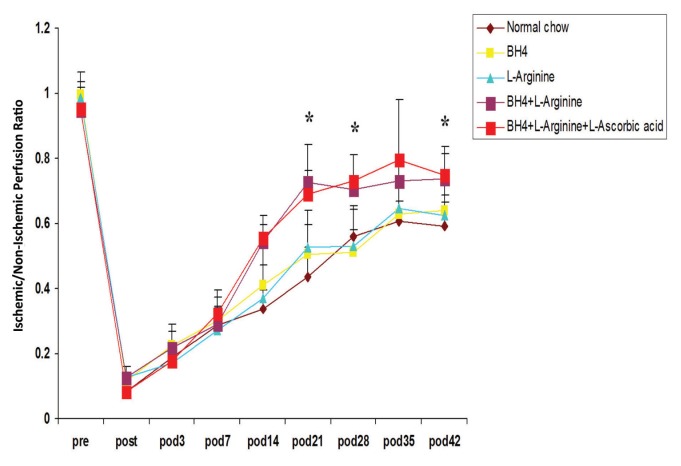

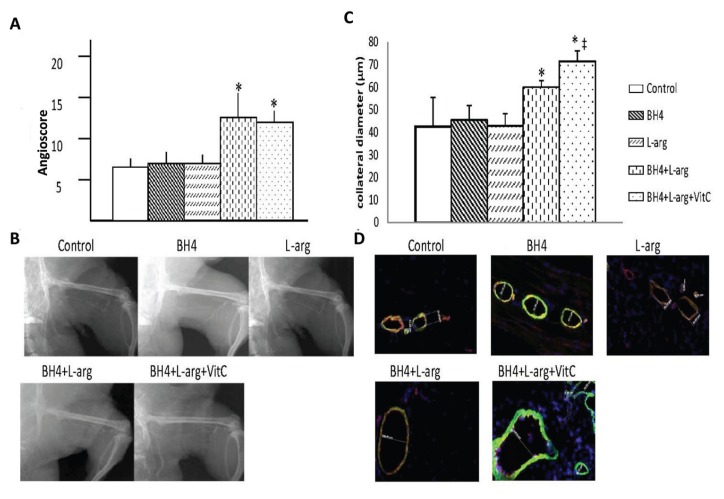

Effects of BH4, l-Arginine and Vitamin C on Hindlimb Blood Flow

Dietary supplementation significantly increased the recovery of hindlimb blood flow after induction of severe ischemia, and this effect was regimen- and time-dependent (Figure 4). Rats given a single supplement (BH4 or l-arginine) showed similar degrees of perfusion recovery in the foot, and this level was also similar to that noted in rats fed normal chow. Rats provided with two (BH4 + l-arginine) or three (BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C) supplements showed significantly greater recovery of foot perfusion than rats fed normal chow or rats given a single dietary supplement. This difference was evident at the later phase of recovery, on d 21, 28 or 42 after induction of ischemia and also at the time of maximal collateral artery wall remodeling (21). A similar pattern was noted for collateral artery angioscores and collateral diameters determined on d 42 after induction of ischemia (Figures 5A–D). Hence, the angioscore and collateral diameters were significantly greater in rats given two (BH4 + l-arginine) or three (BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C) supplements than in rats fed normal chow or in rats given a single supplement. In addition, rats fed BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C showed significantly greater angioscores and collateral diameters than rats fed BH4 + l-arginine. Despite this increase in collateral artery diameters when all three supplements were given, we did not detect a statistically significant increase in resting foot blood flow. Resting blood flow is low in skeletal muscle and increases up to 10-fold during exercise. On the basis of our previous work, we would anticipate detecting significant increases in blood flow under exercise conditions (22).

Figure 4.

Effects of BH4, l-arginine and vitamin C on blood flow recovery after induction of hindlimb ischemia. LDPI data, expressed as the ratio of blood flow from the ischemic to non-ischemic hindlimbs, was determined before, immediately after and then serially over the ensuing 6 wks. Group identity is shown in the color key. Data are means ± sd; n = 6. *p < 0.05 for BH4 + l-arginine or BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C groups versus all other groups.

Figure 5.

Effects of BH4, l-arginine (L-arg) and vitamin C (VitC) on collateral enlargement after induction of hindlimb ischemia. (A) The angioscore, determined 42 d after the induction of hindlimb ischemia and calculated as described in the text, was greater in rats receiving BH4 + l-arginine or BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C than in all other groups. Data are means ± sd; n = 6. *p < 0.05 for BH4 + l-arginine or BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C groups versus all other groups. (B) Representative angiogram from each study group. (C) Greater collateral artery diameters were observed in rats receiving BH4 + l-arginine; addition of vitamin C further increased collateral diameter. Data are means ± sd; n = 6. *p < 0.05 for BH4 + l-arginine or BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C groups versus all other groups; ‡p < 0.05 versus BH4 + l-arginine group. (D) Representative images for collateral diameter.

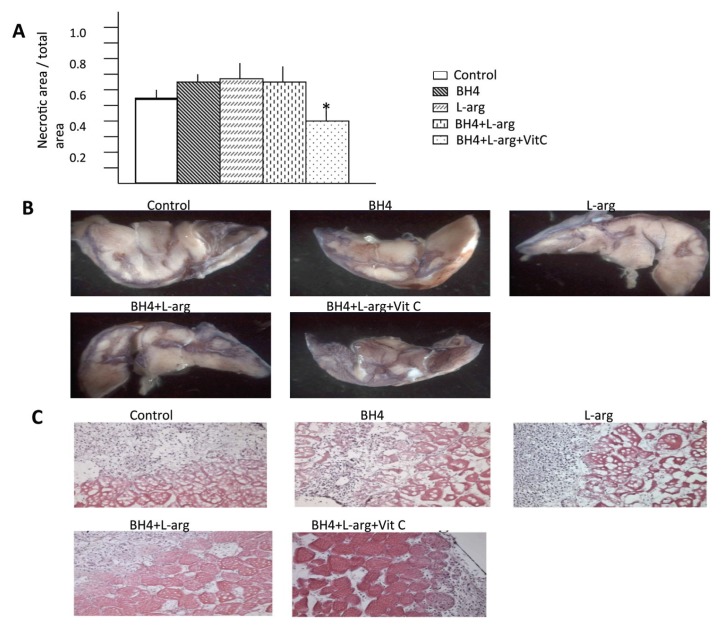

Effects of Oral BH4, l-Arginine and Vitamin C on Gastrocnemius Muscle Necrosis

The extent of gastrocnemius necrosis was affected by the provision of dietary supplements. Rats given a single supplement (BH4 or l-arginine) or the combination of these agents manifest a similar degree of gastrocnemius muscle necrosis. Moreover, the extent of necrosis noted in these dietary intervention groups was similar to that noted in rats fed normal chow, that is, these dietary regimens did not improve postischemic muscle integrity. However, rats provided with all three dietary supplements had significantly less gastrocnemius necrosis than rats fed normal chow, rats provided with a single dietary supplement or rats given the combination of BH4 + l-arginine. This difference was evident on macroscopic and microscopic levels. The percentage of the cut surface of the ischemic gastrocnemius muscle that was necrotic, determined by NBT staining, was significantly less in the BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C group than in all other groups (Figures 6A, B). Groups fed normal chow, or supplemented with BH4, or l-arginine, or both agents, demonstrated similar histological evidence of severe necrosis: muscle nuclei were nearly absent, intra-myofiber vacuolization was substantial and the distance between myofibers was large (Figure 6C). A pronounced inflammatory infiltrate was also present in these groups. In contrast, the BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C group demonstrated good preservation of muscle histology and only a limited inflammatory cell infiltrate.

Figure 6.

The effects of BH4, l-arginine (L-arg) and vitamin C (VitC) on necrosis in the ischemic gastrocnemius muscle. (A) Gastrocnemius muscle was removed 7 d after induction of hindlimb ischemia. Transverse sections of this muscle were stained with nitroblue tetrazolium to determine the ratio of necrotic versus viable surface area. This ratio was less in rats receiving BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C than in all other groups. Data are means ± sd; n = 6. *p < 0.05 for BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C groups versus all other groups. (B) Representative images from each study group. (C) Histological sections of gastrocnemius muscle taken from the ischemic hindlimb 7 d after the induction of hindlimb ischemia were stained with H&E. Representative sections are shown. Note the loss of myofibers and the intense cellular infiltrate in the control, BH4 and l-arginine groups. Best preservation of muscle architecture was consistently observed in rats receiving BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C.

DISCUSSION

The study hypothesis that dietary co-supplementation with BH4, l-arginine and vitamin C act synergistically to decrease oxidant stress, increase NO and thereby improve limb perfusion and tissue recovery in response to acute hindlimb ischemia was supported by our findings. Interestingly, two patterns of effect emerged. Cosupplementation with BH4 + l-arginine increased the dependent variables NO bioavailability, foot perfusion, the collateral artery angioscore and collateral artery diameters more than the addition of either component separately, whereas the addition of vitamin C provided a further beneficial effect on these variables. In addition, coadministration of all three dietary supplements had a significantly greater effect than BH4 or l-arginine, given individually or in combination, when the dependent variables of oxidative stress (nitrotyrosine accumulation and GSH-to-GSSG ratio) or muscle necrosis were measured.

eNOS and P-eNOS expression, Ca2+-dependent NOS activity, tissue NOx levels, foot perfusion, the collateral artery angioscore and collateral diameters are linked by established cause-and-effect relationships. eNOS-derived NO is a potent vasodilator (2); hence, the increased eNOS expression and activity present in the BH4 + l-arginine group should result in an NO-dependent increase in foot perfusion, and this expectation was realized by our findings. Moreover, eNOS-derived NO is a critical determinant in the response to hindlimb ischemia (23–25). This effect is direct, because we and others have shown that eNOS-derived NO is essential to collateral artery remodeling (21,26). These effects include mobilization of mononuclear cells from the bone marrow and their subsequent homing to the ischemic hindlimb (27). Once there, those cells participate in postischemic arteriogenesis, the process wherein existing collateral arteries undergo remodeling designed to restore vascular conductance (28). This process was evidenced by the increased angioscores and collateral diameters, quantitative markers of collateral artery enlargement, in rats provided with BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C dietary supplements.

Vitamin C likely exerted its beneficial effects in this study through a variety of molecular mechanisms. In its capacity as an antioxidant, it enhances NO bioavailability by quenching O2−, thus limiting the inactivation of NO that occurs when O2− and NO combine to produce OONO−(3). Vitamin C also stabilizes existing BH4 (8) and increases endothelial BH4 synthesis (29), thus minimizing eNOS “uncoupling,” which, in turn, lessens generation of O2− by eNOS and reduces vascular oxidant stress (7). However, BH4 is itself a potent antioxidant (7), and administration of exogenous BH4 has been established to increase endothelial BH4 levels (30). Moreover, l-arginine directly stimulates eNOS expression (31); enhances eNOS activity by a receptor-dependent, G protein–linked process (32); and limits the inhibitory effect of asymmetric dimethylarginine on eNOS-derived NO production (33). A series of studies proved that metabolic intervention with antioxidants (vitamin C) and l-arginine can promote the beneficial effects in ischemia-induced vasculogenesis beyond that provided by bone marrow mononuclear cells alone due to increased NO/eNOS bioactivity, decreased oxidative stress and antiinflammatory action in ischemic tissue (34–38). We propose that under the experimental conditions imposed by hindlimb ischemia, addition of vitamin C to BH4 + l-arginine significantly decreased oxidative stress, increased NO bioavailability, increased collateral artery diameters and accordingly decreased tissue necrosis. It may also restore BH4 or NO levels, since we observed an increase in P-eNOS expression and NO bioavailability.

Ca2+-independent NOS activity and tissue nitrotyrosine accumulation were significantly lower in rats receiving all three dietary supplements than in rats receiving BH4 or l-arginine, or a combination of the two. When measured by methods used herein, Ca2+-independent NOS activity is an authentic reflection of iNOS activity, inasmuch as the assay was conducted in vitro, in the absence of shear stress that can activate eNOS in the absence of Ca2+ via phosphorylation (39). The marked elevation of iNOS activity in rats fed normal chow indicates the presence of postischemia inflammation, which is also evidenced by the cellular inflammatory infiltrate in this group. Nitrotyrosine accumulation is indicative of OONO−-induced necrosis (40), and it is interesting that the group that exhibited the least amount of tissue necrosis (that is, rats provided with all three supplements) also had the least nitrotyrosine accumulation. Moreover, rats in the triple therapy group demonstrated a virtual absence of nitrotyrosine. We interpret the present findings to indicate that vitamin C provided an antioxidant effect that limited tissue injury generated by inflammatory cells for which action depends, in part, on oxidant production (for example, neutrophils and macrophages). This effect could be direct because of the antioxidant activity of vitamin C, or indirect, because of the beneficial effect of vitamin C on BH4 levels (8,29), insofar as BH4 also exhibits potent antioxidant activity (7).

Although it is well established that endothelial dysfunction related to vascular oxidant stress is a critical factor in PAD pathogenesis, dietary supplementation with l-arginine or antioxidants, such as vitamin C, has had equivocal effects on long-term outcome (12,13,16). Dietary supplementation with l-arginine alone has a beneficial effect when given acutely, that is, via intravenous infusion (14) or for short duration (2 months) (15), and these clinical results are consistent with the positive effects observed in rats provided with dietary l-arginine. However, long-term administration of l-arginine (6 months) not only failed to demonstrate a beneficial effect, but resulted in a degree of eNOS-dependent vascular reactivity significantly less than that of the placebo group (16). The present findings demonstrated increased iNOS activity after induction of ischemia. If a similar circumstance is present in PAD, then the singular dietary supplementation with l-arginine, the substrate for all NOS isoforms, might serve to worsen vascular inflammation, a critical participant in the pathogenesis of PAD (1). In addition, if l-arginine is administrated in a state of oxidant stress, as is present in many patients with PAD, eNOS is uncoupled and produces ONOO− rather than NO. Vitamin C reduces vascular inflammation (41) and improves redox balance (11) and eNOS-dependent vascular reactivity (10), but these effects have only been evaluated on a short-term basis, whereas retrospective cross-sectional studies have failed to confirm that dietary supplementation with antioxidants improves PAD outcome (12,13). We interpret the recent findings to indicate that provision of BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C acting synergistically might prove to be a useful therapeutic alternative in PAD treatment. To this end, the use of sapropterin dihydrochloride, a synthetic form of (6R)-l-erythro-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin recently approved for the treatment of phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency (42), might provide a practical means for the provision of BH4.

CONCLUSION

Cosupplementation with BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C resulted in increased eNOS activity and NO concentration as well as greater foot blood flow recovery than rats receiving normal chow or either agent separately. The addition of vitamin C to the BH4 + l-arginine regimen further reduced oxidant stress and increased collateral diameters and reduced tissue injury in is-chemic muscles (Figure 7). The clearly superior outcome of rats provided with BH4 + l-arginine + vitamin C warrants investigation of a cosupplementation strategy as a therapeutic alternative in PAD. However, additional preclinical studies need to be undertaken to establish proof of principle in experimental models of hindlimb ischemia in which ischemia is induced gradually and under conditions of systemic oxidant stress such as type 2 diabetes or hyper-cholesterolemia (43).

Figure 7.

Schematic illustration that a regimen of three dietary supplements combined can increase NO bioavailability and decrease oxidative stress, accordingly increase blood flow recovery and reduce tissue necrosis. A•, ascorbate; AH−, dehydroascorbate. BH3•, BH3−.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant RO-1 HL-75353 (to LM Messina), as well as grants from the the Wayne and Gladys Valley Foundation (to LM Messina).

Footnotes

Online address: http://www.molmed.org

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that they have no competing interests as defined by Molecular Medicine, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and discussion reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coutinho T, Rooke TW, Kullo IJ. Arterial dysfunction and functional performance in patients with peripheral artery disease: a review. Vasc Med. 2011;16:203–11. doi: 10.1177/1358863X11400935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marletta MA. Nitric oxide synthase structure and mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12231–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterson TE, et al. Opposing effects of reactive oxygen species and cholesterol on endothelial nitric oxide synthase and endothelial cell caveolae. Circ Res. 1999;85:29–37. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuzkaya N, Weissmann N, Harrison DG, Dikalov S. Interactions of peroxynitrite, tetrahydrobiopterin, ascorbic acid, and thiols: implications for uncoupling endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol. Chem. 2003;278:22546–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bevers LM, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin, but not L-arginine, decreases NO synthase uncoupling in cells expressing high levels of endothelial NO synthase. Hypertension. 2006;47:87–94. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000196735.85398.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt TS, Alp NJ. Mechanisms for the role of tetrahydrobiopterin in endothelial function and disease. Clin Sci. 2007;113:47–63. doi: 10.1042/CS20070108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heller R, et al. L-ascorbic acid potentiates endothelial nitric oxide synthesis via a chemical stabilization of tetrahydrobiopterin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langlois M, Duprez D, Delanghe J, De Buyzere M, Clement DL. Serum vitamin C concentration is low in peripheral arterial disease and is associated with inflammation and severity of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2001;103:1863–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.14.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silvestro A, et al. Vitamin C prevents endothelial dysfunction induced by acute exercise in patients with intermittent claudication. Atherosclerosis. 2002;165:277–83. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wijnen MH, et al. Antioxidants reduce oxidative stress in claudicants. J Surg Res. 2001;96:183–7. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.6078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnan PT, Thomson M, Fowkes FG, Prescott RJ, Housley E. Diet as a risk factor for peripheral arterial disease in the general population: the Edinburgh Artery Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;57:917–21. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/57.6.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klipstein-Grobusch K, et al. Dietary antioxidants and peripheral arterial disease: the Rotterdam Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:145–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Böger RH, et al. Restoring vascular nitric oxide formation by L-arginine improves the symptoms of intermittent claudication in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease. J Am Coll Card. 1998;32:1336–44. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maxwell AJ, Anderson BE, Cooke JP. Nutritional therapy for peripheral arterial disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of HeartBar. Vasc Med. 2000;5:11–9. doi: 10.1177/1358836X0000500103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson AM, Harada R, Nair N, Balasubramanian N, Cooke JP. L-arginine supplementation in peripheral arterial disease: no benefit and possible harm. Circulation. 2007;116:188–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ueda S, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin restores endothelial function in long-term smokers. J Am Coll Card. 2000;35:71–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heitzer T, Krohn K, Albers S, Meinertz T. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation by increasing nitric oxide activity in patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2000;43:1435–8. doi: 10.1007/s001250051551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan J, et al. Oral tetrahydrobiopterin improves the beneficial effect of adenoviral-mediated eNOS gene transfer after induction of hindlimb ischemia. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1482–9. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong HJ, Hsiao G, Cheng TH, Yen MH. Supplemention with tetrahydrobiopterin suppresses the development of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2001;38:1044–8. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.095331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park B, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase affects both early and late collateral arterial adaptation and blood flow recovery after induction of hindlimb ischemia in mice. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:165–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brevetti LS, et al. Exercise induced hyperemia unmasks regional blood flow deficit in experimental hindlimb ischemia. J Surg Res. 2001;98:21–6. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan J, Tang GL, Wang R, Messina LM. Optimization of adenovirus-mediated endothelial nitric oxide synthase delivery in rat hindlimb ischemia. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1640–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu J, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase is critical for ischemic remodeling, mural cell recruitment, and blood flow reserve. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10999–1004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501444102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lloyd PG, Yang HT, Terjung RL. Arteriogenesis and angiogenesis in rat ischemic hindlimb: role of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H2528–38. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mees B, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity is essential for vasodilation during blood flow recovery but not for arteriogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1926–33. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.145375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aicher A, et al. Essential role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase for mobilization of stem and progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2003;9:1370–6. doi: 10.1038/nm948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helisch A, Schaper W. Arteriogenesis: the development and growth of collateral arteries. Microcirculation. 2003;10:83–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang A, Vita JA, Venema RC, Keaney JF., Jr Ascorbic acid enhances endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activity by increasing intracellular tetrahydrobiopterin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17399–406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawabe K, Wakasugi KO, Hasegawa H. Tetrahydrobiopterin uptake in supplemental administration: elevation of tissue tetrahydrobiopterin in mice following uptake of the exogenously oxidized product 7,8-dihydrobiopterin and subsequent reduction by an anti-folate-sensitive process. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;96:124–33. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0040280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Javanmard SH, Nematbakhsh M, Nahomoodi F, Mohajeri MR. L-Arginine supplementation enhances eNOS expression in experimental model of hypercholesterolemic rabbits aorta. Pathophysiology. 2009;16:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joshi MS, et al. Receptor-mediated activation of nitric oxide synthesis by arginine in endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9982–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506824104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Böger RS, Ron ES. L-arginine improves vascular function by overcoming the deleterious effects of ADMA, a novel cardiovascular risk factor. Altern Med Rev. 2005;10:14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Napoli C, et al. Beneficial effects of concurrent autologous bone marrow cell therapy and metabolic intervention in ischemia-induced angiogenesis in the mouse hindlimb. PNAS. 2005;47:17202–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508534102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Nigris F, et al. Therapeutic effects of concurrent autologous bone marrow cell infusion and metabolic intervention in ischemia-induced angiogenesis in the hypercholesterolemic mouse hindlimb. Int J Cardiol. 2007;117:238–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Nigris F, et al. Therapeutic effects of autologous bone marrow cells and metabolic intervention in the ischemic hindlimb of spontaneously hypertensive rats involved reduced cell senescence and CXCR4/Akt/eNOS pathways. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:424–33. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31812564e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Napoli C, et al. Beneficial effects of autologous bone marrow cell infusion and antioxidants/L-arginine in patients with chronic critical limb ischemia. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15:709–18. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283193a0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balestrieri M, et al. Therapeutic angiogenesis in diabetic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice using bone marrow cells, functional hemangioblasts and metabolic intervention. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209:403–14. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ayajiki K, Kindermann M, Hecker M, Fleming I, Busse R. Intracellular pH and tyrosine phosphorylation but not calcium induce shear stress-induced nitric oxide production in native endothelial cells. Circ Res. 1996;78:750–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.5.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beckman JS, Koppenol WH. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1424–37. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aguirre R, May JM. Inflammation in the vascular bed: importance of vitamin C. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;119:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamamizu K, Shinozaki K, Ayajiki K, Gemba M, Okamura T. Oral administration of both tetrahydrobiopterin and L-arginine prevents endothelial dysfunction in rats with chronic renal failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;49:131–9. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31802f9923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yagai Y, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanism regulating blood flow recovery in acute versus gradual femoral artery occlusion are distinct in the mouse. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:1546–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.07.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]