Abstract

Objective

Low levels of serum circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D have been correlated with many health conditions, including chronic pain. Recent clinical practice guidelines define vitamin D levels < 20 ng/mL as deficient and values of 21–29 ng/mL as insufficient. Vitamin D insufficiency, including the most severe levels of deficiency, is more prevalent in black Americans. Ethnic and race group differences have been reported in both clinical and experimental pain, with black Americans reporting increased pain. The purpose of this study was to examine whether variation in vitamin D levels contribute to race differences in knee osteoarthritic pain.

Methods

The sample consisted of 94 participants (75% female), including 45 blacks and 49 whites with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Average age was 55.8 years (range 45–71 years). Participants completed a questionnaire on knee osteoarthritic symptoms and underwent quantitative sensory testing, including measures of heat and mechanical pain sensitivity.

Results

Blacks had significantly lower levels of vitamin D compared to whites, demonstrated greater clinical pain, and showed greater sensitivity to mechanical and heat pain. Low levels of vitamin D predicted increased experimental pain sensitivity, but did not predict self-reported clinical pain. Group differences in vitamin D significantly predicted group differences in heat pain and pressure pain thresholds on the index knee and ipsilateral forearm.

Conclusion

These data demonstrate race differences in experimental pain are mediated by differences in vitamin D level. Vitamin D deficiency may be a risk factor for increased knee osteoarthritic pain in black Americans.

Keywords: vitamin D, pain, osteoarthritis, racial disparities in health

The last decade has witnessed a dramatic increase in research related to the nonskeletal effects of vitamin D. In its known role as a vitamin, this micronutrient aids calcium absorption. However, recent research on vitamin D has focused on its hormonal actions. Recommended daily intake of vitamin D has historically been aimed at primary prevention of osteomalacia and osteoporosis. In its biologically active form, vitamin D is a secosteroid involved in regulating cell differentiation, proliferation, angiogenesis, and apoptosis (1). Vitamin D is synthesized through the skin with adequate exposure to ultraviolet-B (UVB) light. Following synthesis and conversion, vitamin D is hydroxylated in the liver, then the kidneys. Vitamin D receptors can be found on nearly all nucleated cells (2). Hypovitaminosis D has been correlated with diabetes, cancer, and decreased immunity (1).

Less than sufficient levels of serum circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D (hereafter referred to as vitamin D) have been noted across populations in epidemiological studies. Seasonal variation in the angle of the sun's UVB rays decreases opportunities for vitamin D synthesis in northern latitudes and in the winter months. Other factors contributing to inadequate vitamin D levels include more time spent indoors, increased use of sunscreen, and the prevalence of obesity (3). As a fat soluble nutrient, vitamin D is sequestered in fat cells, decreasing its availability for hormonal actions in the bloodstream. With aging, the body's ability to synthesize vitamin D in the skin lessens (3); thus, older adults are at greater risk for inadequate vitamin D levels. Additionally, vitamin D synthesis requires longer periods of sun exposure for those with dark skin pigmentation. Thus, low levels of vitamin D are prevalent in black Americans, including the most severe levels of deficiency. Estimates indicate 70% of white Americans and over 95% of black Americans are vitamin D deficient (4). Greater vitamin D deficiency in black Americans may, in part, explain the increased incidence of chronic health conditions and provide a key to reducing health disparities (3–5).

The optimal serum concentration of vitamin D is currently debated, but believed to be between 30–60 ng/mL. Recent clinical practice guidelines define vitamin D levels < 20 ng/mL as deficient and values of 21–29 ng/mL as insufficient (6). It has been suggested that different normative values of vitamin D may be warranted for black and white Americans based on the inverse relationship between vitamin D and parathyroid hormone levels (7). However, variation in the vitamin D-parathyroid hormone relationship by race and age is not fully understood and clinical trials on vitamin D supplementation are needed (7–10). In 2011, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D, (11) increased the recommended daily intake of vitamin D from 400 to 600 international units (IU) per day. Many experts feel this dose remains too low (12). The IOM report recommends interventional research on vitamin D supplementation to ascertain its effect on disease, aging, and racial health disparities and, thus, raised the safe daily dose to 4,000 IU per day. Though vitamin D has been correlated with many health conditions, few studies have considered the relationship of vitamin D to chronic pain (13–17).

Chronic pain is a disease. The 2011 IOM report, Relieving Pain in America, (18) estimates annual spending on pain to be between $560–635 billion. More than 50% of older adults contend with osteoarthritis pain – the most common joint condition and the leading cause of disability in older adults (19–21). Research suggests the brain reorganizes in the presence of chronic pain, which may reflect fundamental changes in how the brain processes pain-related information (22). Despite advances in the basic science understanding of pain pathways and processing, there remain vast individual differences in response to the clinical treatment of pain. Furthermore, pain remains undertreated, especially for older adults and non-white populations (23–27). Previous research in our laboratory has found ethnic differences in quantitative sensory testing, with blacks reporting increased pain sensitivity (28, 29).

The triage theory, proposed by Ames (30), hypothesizes long-term micronutrient deficiencies trigger chronic inflammation. In turn, chronic inflammation leads to chronic health conditions, many of which are characterized by pain as a disabling symptom. Recent research by Lee et al., (31) supports the hypothesis that the etiology of osteoarthritis includes a systemic inflammatory component. Heaney (32) theorizes long-latency chronic diseases are related to insufficient micronutrients over extended periods. The U.S. nutritional recommendations for micronutrients are based on preventing short-latency diseases – and not on optimizing the preventive health effects of micronutrient therapy. These theories may help to explain relationships between vitamin D level and chronic pain. The purpose of this study was to examine whether variation in vitamin D levels contribute to race differences in symptomatic knee osteoarthritic pain. We hypothesize low levels of vitamin D will contribute to self-reported and experimental knee pain and that vitamin D level will mediate the relationship between race (referred to as group differences) and knee pain.

METHODS

Study Design

This cross-sectional study design examined the relationship between low levels of vitamin D and symptomatic knee osteoarthritic pain among older adults. The project is a substudy of an ongoing study examining ethnic differences in knee osteoarthritic pain. The measures and procedures described are limited to those involved in the current study. Participants were recruited at the University of Florida between January, 2010 and August, 2011.

Participants

Participants were recruited via posted fliers, radio and print media ads, clinic recruitment and word-of-mouth referral. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) between 45 and 85 years of age; 2) unilateral or bilateral symptomatic knee osteoarthritis based upon American College of Rheumatology criteria (33), regardless of radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis; and, 3) availability to complete the two-session protocol. Participants were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: 1) prosthetic knee replacement or non-arthroscopic surgery to the affected knee; 2) uncontrolled hypertension (greater than 150/95), heart failure, or history of acute myocardial infarction; 3) peripheral neuropathy; 4) systemic rheumatic disorders including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and fibromyalgia; 5) daily opioid use; 6) cognitive impairment (Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) score ≤ 22); 7) excessive anxiety regarding protocol procedures (intravenous (IV) catheter insertion, quantitative sensory testing procedures); and, 8) hospitalization within the preceding year for psychiatric illness. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board. Participants provided informed consent and were compensated for their participation.

Procedures

Within one week prior to the health assessment session, participants completed study questionnaires. At the health assessment session, the following measures were obtained: anthropometric data, vital signs, health history, current medications, MMSE score, and a bilateral joint exam of the hand and knee joints. Using the American College of Rheumatology criteria (33) for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, the participants' most symptomatic/painful knee was designated as the index knee. Within four weeks of the health assessment session, participants were scheduled for the quantitative sensory testing session. Additional questionnaires were completed prior to and during this session. Quantitative sensory testing procedures included: vital signs, IV insertion for blood collection, and assessment of thermal and mechanical pain.

Self-report measures

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

The CES-D is a 20-item self-report tool that measures symptoms of depression including depressed mood, guilt/worthlessness, helplessness/hopelessness, psychomotor retardation, loss of appetite and sleep disturbance (34). The total score of the CES-D (range 0–60) was used in the current study as an estimate of the degree of participants' depressive symptomatology. The validity and internal consistency of the CES-D in the general population has been reported to be acceptable (35).

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Index of Osteoarthritis (WOMAC)

The WOMAC (36) is frequently used in research to assess symptoms of knee and hip osteoarthritis. The subscales measure pain, stiffness, and physical function. The total WOMAC score was used in analysis (range 0–96). High construct validity and test-retest reliability has been found in paper and computerized versions of the WOMAC (37).

Quantitative sensory testing

Thermal testing procedures

All thermal stimuli were delivered using a computer-controlled Medoc Pathway Thermal Sensory Analyzer (Ramat Yishai, Israel). Heat pain thresholds and heat pain tolerances were assessed using an ascending method of limits. From a baseline of 32°C, thermode temperature increased at a rate of 0.5°C/second until the participant responded by pressing a button on a handheld device. For heat pain threshold, participants were instructed to press the button when the sensation “first becomes painful,” and for tolerance the instruction was to press the button when they “no longer feel able to tolerate the pain.” Three trials for threshold and three for tolerance were delivered to the index knee. The position of the thermode was moved among three sites (the medial joint line, the patella, and the tibial tuberosity distal to the joint) between trials to avoid sensitization and/or habituation of cutaneous receptors. The three individual trials were averaged together to create overall heat pain threshold and heat pain tolerance scores of the index knee. Similarly, three trials for threshold and three for tolerance were delivered to the ipsilateral forearm. The position of the thermode was moved among three sites an inch above the ventral wrist and an inch below the antecubital space. The three individual trials were averaged together to create overall heat pain threshold and heat pain tolerance scores of the ipsilateral forearm.

Mechanical testing procedures

To determine sensitivity at the site of clinical pain, six total trials of pressure pain threshold were assessed at the medial (3 trials) and lateral (3 trials) joint lines of the index knee. Additionally, three pressure pain threshold trials were assessed at the dorsal ipsilateral forearm. A handheld Medoc digital pressure algometer (Ramat Yishai, Israel) was used for the mechanical procedures. An application rate of 30 kilopascals (kPa) per second was used. To assess pressure pain threshold, the examiner applied a constant rate of pressure and the participant was instructed to press a button when the sensation “first becomes painful,” at which time the device recorded the pressure in kPa. The average of the three trials was computed separately for the medial and lateral knee, and subsequently combined to create an overall pressure pain sensitivity score for the index knee. Likewise, the average of the three trials for the ipsilateral forearm was calculated to create an overall pressure pain sensitivity score. The overall pain index scores for the index knee and ipsilateral forearm were included in data analysis.

Vitamin D assay

Serum was collected at the beginning of the quantitative sensory testing session. Following collection, plasma was stored in a −80 degree freezer. The analyte was performed within six months of collection. Vitamin D analysis was performed by high performance liquid chromatography (total 25-hydroxyvitamin D = 25(OH)D2 plus 25(OH)D3). Results were shared with participants and, if their vitamin D level was ≤ 30 ng/mL, they were encouraged to discuss this result with their primary care provider.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS, version 19.0 (IBM). Bivariate relationships among continuously measured variables were assessed using Pearson's correlations, while sex differences were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Group differences by race were adjusted for covariates and assessed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). The relationships between vitamin D level and pain were examined using multiple regressions. The level of significance was set at p < .05.

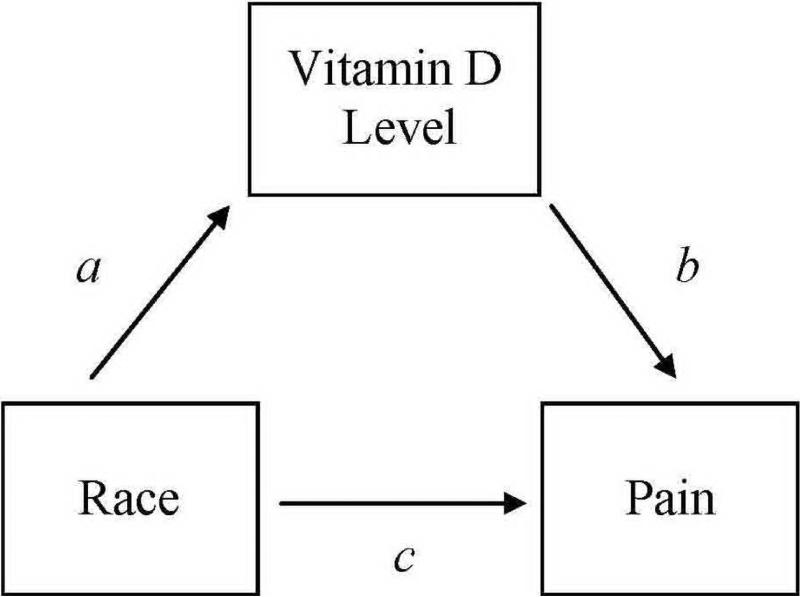

To test whether vitamin D level significantly mediated (Figure 1) the association between race and clinical and experimental pain measures we conducted a bootstrap analysis. Bootstrapping, put forth by Preacher and Hayes (38, 39), is a non-parametric resampling procedure that has been shown to be a viable alternative to the Baron and Kenny (40) approach to testing intervening variable effects. Percentile confidence intervals were used to minimize Type 1 error rate (41). A 95% percentile confidence interval was calculated, using the SPSS macro for simple mediation (39) to determine the significance of the mediator. In the current study, path c represents the total effect of the independent variable (race) on the dependent variable (clinical and experimental pain measures). Path a denotes the effect of race on vitamin D level (mediator) and path b is the effect of vitamin D level on clinical and experimental pain measures. The bootstrapped mediation analysis indicates whether the total effect (path c) is comprised of a significant direct effect (path c') between the race and clinical and experimental pain measures and a significant indirect effect (path a x b) of race on clinical and experimental pain measures through the mediator – vitamin D level.

Figure 1.

Mediation model.

a, race to vitamin D; b, direct effect of vitamin D on pain measures; c, total effect of race on pain measures.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics and Examination of Covariates

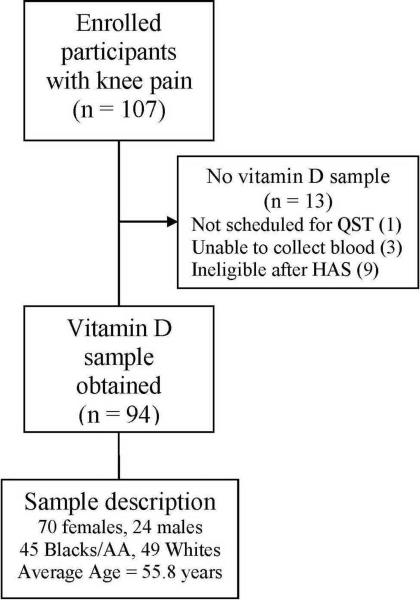

A total of 107 participants with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis were recruited. Vitamin D data were available for 94 participants at the time of analyses. A flow diagram for participant matriculation through the study is included in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Study flow diagram.

QST – quantitative sensory testing; HAS – health assessment session.

Pearson's correlations for key study variables are shown in Table 2. Vitamin D level significantly and inversely correlated with the total WOMAC score, suggesting lower vitamin D levels are associated with greater knee osteoarthritic pain and dysfunction. For experimental pain measures, vitamin D level significantly correlated with heat threshold and heat tolerance on the index knee and on the ipsilateral forearm. Finally, vitamin D level significantly correlated with pressure pain thresholds on the knee and on the ipsilateral forearm. Age and CES-D score did not significantly correlate with vitamin D level; however, CES-D was positively correlated with WOMAC scores and heat pain threshold at the knee.

Table 2.

Descriptive data for key study variables across groups

| Blacks |

Whites |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 45 Females = 31 Males =14 |

n = 49 Females = 39 Males = 10 |

|||||

|

| ||||||

| Variables | Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range |

| Age (years) | 54.6 | 5.4 | 45–68 | 56.9 | 7.7 | 45–71 |

| Vitamin D** (ng/mL) | 19.9 | 8.6 | 8–40 | 28.2 | 8.6 | 7–48 |

| BMI (%)* | 32.4 | 8.0 | 18–50 | 29.0 | 6.7 | 19–49 |

| CES-D | 16.2 | 6.5 | 0–30 | 16.7 | 5.2 | 0–38 |

| WOMAC* | 41.5 | 21.7 | 4–94 | 29.4 | 18.8 | 4–86 |

| Heat Pain Threshold Knee (deg C) | 41.3 | 3.0 | 36–46 | 42.7 | 2.9 | 36–48 |

| Heat Pain Tolerance Knee (deg C)** | 44.6 | 3.3 | 35–49 | 47.0 | 2.1 | 38–51 |

| Heat Pain Threshold Forearm (deg C)* | 40.9 | 3.3 | 34–47 | 42.8 | 2.7 | 35–47 |

| Heat Pain Tolerance Forearm (deg C)** | 45.2 | 2.7 | 37–50 | 47.0 | 2.1 | 39–51 |

| Pressure Pain Threshold Knee (kPa)* | 263.6 | 149.0 | 53–588 | 362.4 | 164.4 | 81–598 |

| Pressure Pain Threshold Forearm (kPa)* | 233.3 | 153.2 | 51–748 | 275.9 | 148.9 | 77–677 |

Note:

p < 0.05;

p < 0.001

Women demonstrated lower heat pain tolerance at the forearm (F(1,92) = 4.76, p = .03) and lower pressure pain thresholds at the knee (F(1,92) = 12.92, p = .001) as well as forearm (F(1,92) = 13.75, p < .001) compared to men. There were a greater proportion of black current smokers compared to white current smokers (χ2 = 4.64, p < .05). However, clinical and experimental pain, as well as vitamin D level, did not significantly differ according to smoking status (current versus non-smoker; p's > .05). Participant age, sex, BMI, and CES-D score correlated with pain response and were included as statistical controls in all subsequent data analyses.

Group Differences in Clinical and Experimental Pain

Using the total WOMAC score, ANCOVA revealed a significant group difference (F(1,88) = 5.67, p = .02). As can be seen in Table 2, the average WOMAC score for black participants was 41.5 (SD = 21.66), compared to a mean of 29.4 (SD = 18.76), for white participants, indicating blacks reported more knee pain, stiffness, and limitations in physical function. Additionally, black participants demonstrated greater sensitivity to experimental pain measures compared to whites. For example, blacks demonstrated significantly lower mean heat pain threshold (F(1,88) = 5.36, p = .02) and heat pain tolerance (F(1,88) = 23.14, p < .001) on the index knee. Similar results were found for the ipsilateral forearm, such that blacks demonstrated significantly lower heat pain threshold (F(1,88) = 9.32, p = .003) and heat pain tolerance (F(1,88) = 17.81, p < .001) compared to whites. For mechanical pain, black participants demonstrated significantly lower mean pressure pain threshold on the index knee (F(1,88) = 10.13, p = .002) and the ipsilateral forearm (F(1,88) = 3.96, p = .05) compared to whites.

Group Differences in Vitamin D Level

Adjusted for covariates, ANCOVA revealed that black participants were characterized by significantly lower mean vitamin D levels than their white counterparts (F(1,88) = 16.03, p < .001). Average vitamin D level for black participants was 19.9 ng/mL (SD = 8.6), which based on the most recent guidelines (6) indicates vitamin D deficiency, compared to a mean of 28.2 ng/mL (SD = 8.6) for whites, which indicates vitamin D insufficiency. Low levels of vitamin D were observed across the sample, but were disproportionately found in black participants: 38 of 45 (84%) black participants had vitamin D levels < 30 ng/mL compared to 25 of 49 (51%) white participants with vitamin D levels < 30 ng/mL (χ2 = 11.86, p < .001).

Vitamin D Level and Pain

Adjusted multiple regression analyses, controlling for the effects of age, sex, BMI, CES-D, and group, revealed vitamin D level was not significantly associated with the total WOMAC score (β = −0.06, p = .56). However, low levels of vitamin D predicted increased pain sensitivity and lower experimental pain thresholds. Diminished vitamin D levels were significantly associated with lower heat pain thresholds on the index knee (β = 0.23, p = .05) and ipsilateral forearm (β = 0.25, p = .03). Additionally, lower vitamin D levels were significantly associated with greater sensitivity to pressure pain (i.e., lower threshold) on the index knee (β = 0.23, p = .02) and the ipsilateral forearm (β = 0.31, p < .01). However, vitamin D level was not significantly related to heat pain tolerance on the index knee (β = 0.10, p = .37) or the ipsilateral forearm (β = 0.13, p = .22). Accordingly, only heat pain thresholds and pressure pain thresholds on the index knee and ipsilateral forearm were examined in the mediational analyses.

Testing Vitamin D Level as a Simple Mediator

The indirect effects of group differences in heat pain thresholds and pressure pain thresholds through vitamin D level (i.e., simple mediation) were tested. Table 3 displays the results of the analyses that examined whether vitamin D level mediated group differences in heat pain thresholds on the index knee (Model 1) and ipsilateral forearm (Model 2) after adjusting for covariates. Vitamin D level was found to significantly mediate the group difference in heat pain threshold on the index knee (95% percentile confidence interval: 0.01 to 1.11) and on the ipsilateral forearm (95% percentile confidence interval: 0.09 to 1.22) using the bootstrapped percentile confidence interval, with 5,000 resamples. These results indicate indirect effects through vitamin D level are significantly different from zero. Thus, group differences in heat pain thresholds are mediated by group differences in vitamin D levels. More specifically, blacks possessed lower vitamin D levels than whites and, in turn, lower vitamin D levels significantly predicted lower heat pain thresholds at the index knee and ipsilateral forearm.

Table 3.

Vitamin D mediates group differences in heat pain threshold at the index knee (Model 1) and ipsilateral forearm (Model 2)

| Effect | Coefficient | SE | t | Sig. | 95% percentile confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||||

| c | 1.49 | 0.64 | 2.32 | 0.0229 | |

| a | 7.39 | 1.85 | 4.00 | 0.0001 | |

| b | 0.07 | 0.04 | 1.96 | 0.0531 | |

| c' | 0.96 | 0.69 | 1.39 | 0.1667 | |

| a × b | 0.51 | 0.28 | d | (0.01 – 1.11) | |

| Model 2 | |||||

| c | 1.97 | 0.64 | 3.05 | 0.0030 | |

| a | 7.39 | 1.85 | 4.00 | 0.0001 | |

| b | 0.08 | 0.04 | 2.27 | 0.0258 | |

| c' | 1.36 | 0.68 | 1.98 | 0.0506 | |

| a × b | 0.60 | 0.29 | d | (0.09 – 1.22) | |

Table 3 shows unstandardized coefficients for the mediated effect of group differences in heat pain threshold at the index knee and ipsilateral forearm through vitamin D level, controlling for age, sex, BMI, and CES-D. a, race to vitamin D; b, direct effect of vitamin D on heat pain threshold; c, total effect of race on heat pain threshold; c', direct effect of race on heat pain threshold, controlling for vitamin D; a × b, indirect effect of race on heat pain threshold through vitamin D.

A p-value for the indirect effect is not provided because such a p-value is contingent upon a normal distribution of the indirect effect. Given that the product of the a and b path coefficients is always positively skewed, interpretation of this p-value can be misleading (40).

Table 4 displays the results of the analyses that examined whether vitamin D level also mediated group differences in pressure pain thresholds on the index knee (Model 3) and ipsilateral forearm (Model 4) after adjusting for covariates. Vitamin D level was shown to significantly mediate the group differences in pressure pain threshold (95% percentile confidence interval: 3.43 – 60.86) and on the ipsilateral forearm (95% percentile confidence interval: 12.44 – 67.55) using the bootstrapped percentile confidence interval, with 5,000 resamples. As mentioned above, these results indicate indirect effects through vitamin D level are significantly different from zero. Thus, group differences in pressure pain thresholds are mediated by group differences in vitamin D levels.

Table 4.

Vitamin D mediates group differences in pressure pain threshold at the index knee (Model 3) and ipsilateral forearm (Model 4)

| Effect | Coefficient | SE | t | Sig. | 95% CI Bias Corrected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 3 | |||||

| c | 95.88 | 30.12 | 3.18 | 0.0020 | |

| a | 7.39 | 1.85 | 4.00 | 0.0001 | |

| b | 4.00 | 1.70 | 2.36 | 0.0205 | |

| c' | 66.31 | 31.93 | 2.08 | 0.0408 | |

| a × b | 29.10 | 14.84 | d | (3.43 – 60.86) | |

| Model 4 | |||||

| c | 60.21 | 30.26 | 1.99 | 0.0497 | |

| a | 7.39 | 1.85 | 4.00 | 0.0001 | |

| b | 4.95 | 1.68 | 2.96 | 0.0040 | |

| c' | 23.61 | 31.54 | 0.75 | 0.4561 | |

| a × b | 36.34 | 14.27 | d | (12.44 – 67.55) | |

Table 4 shows unstandardized coefficients for the mediated effect of group differences in pressure pain threshold at the index knee and ipsilateral forearm through vitamin D level, controlling for age, sex, BMI, and CES-D. a race to vitamin D; b, direct effect of vitamin D on pressure pain threshold; c, total effect of race on pressure pain threshold; c', direct effect of race on pressure pain threshold, controlling for vitamin D; a × b indirect effect of race on pressure pain threshold through vitamin D.

A p-value for the indirect effect is not provided because such a p-value is contingent upon a normal distribution of the indirect effect. Given that the product of the a and b path coefficients is always positively skewed, interpretation of this p-value can be misleading (40).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we examined the extent to which vitamin D level mediated the relationship between race and pain in older adults with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Results revealed group differences in response to experimental pain, but not self-reported pain, for blacks and whites are mediated by group differences in vitamin D level. Low levels of vitamin D mediated the relationship between race and experimental pain in older adults with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. The study hypothesis expected these findings at the painful knee. Similar results were demonstrated at a non-painful testing site on the forearm. Even in a sunny southern environment, low levels of vitamin D were endemic across the sample with black participants possessing more pronounced levels of vitamin D deficiency. Black participants demonstrated greater pain sensitivity in thermal and mechanical testing at the index knee and the ipsilateral forearm. These findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating significant differences in responses to quantitative sensory testing in black Americans (28, 29, 42).

Although an established link between low levels of vitamin D and pain due to osteomalacia exist (1), no clear biological or psychological mechanisms explain how low levels of vitamin D may affect pain sensitivity, or causally relate to other chronic pain conditions. Interestingly, significant mediation was found for heat pain threshold but not for pain tolerance. This outcome suggests vitamin D level may be related to pain pathways involved in initial perception of pain but not how much pain an individual can tolerate. Pain tolerance is dependent, in part, on individuals' willingness to endure noxious stimulation which is not necessarily related to vitamin D level. In contrast, since there are vitamin D receptors in nucleated cells throughout the peripheral and central nervous system, less than sufficient levels of vitamin D could impact both the transmission and modulation of painful stimuli (16, 21, 31, 43). Using a rodent model, Tague and colleagues (44) found vitamin D deficient rats had increased muscle innervation by nociceptors leading to reduced pain threshold for mechanical stimulation in hindlimb musculature. In vitro cultures revealed that vitamin D level was inversely correlated with growth of sensory neurons, leading the authors to hypothesize that vitamin D deficiency may induce muscle pain by stimulating nociceptor growth. Furthermore, inflammatory processes contribute to increased pain sensitivity among individuals with osteoarthritis (21, 31). Sufficient levels of cellular vitamin D have a protective effect on cell function and are believed to reduce inflammation (1, 45). Thus, alterations in inflammation attributable to low levels of vitamin D may precipitate increased pain among individuals with osteoarthritis. Less than sufficient levels of vitamin D may explain the increase in symptomatic osteoarthritis without a concurrent increase in radiographic osteoarthritis (46).

In this cohort, the participants' CES-D score did not significantly correlate with vitamin D level. However, other research has found an association between low levels of vitamin D and increased symptoms of depression. In a four-year study of nearly 12,600 participants, low levels of vitamin D were associated with depression, especially in those that had previous episodes (47). Higher levels of vitamin D were associated with less depressive symptoms, even among those with a history of depression. It is possible that vitamin D has a direct effect on mood since vitamin D supplementation in a placebo-controlled double-blind trial was shown to improve the mood and affect of individuals diagnosed with seasonal affective disorder (48). Vitamin D receptors are ample in structures and cells of the brain and may contribute to overall brain health and enhanced nerve conduction (49). Given the substantial overlap between negative mood and chronic pain, vitamin D insufficiency may modulate pain perception through affective pathways (50).

As in most research, these findings should be interpreted in light of the study limitations. Participants represented a convenience sample of community-dwelling adults and older adults. The age range of participants was between 45–71 years; however, the average age of 55.8 years represents a younger cohort. Though black participants were slightly younger than whites, they reported higher levels of osteoarthritic-related pain. The cross-sectional examination of vitamin D level and clinical and experimental pain does not permit a full understanding of the direction of the relationship between vitamin D level and chronic pain. It is possible people with osteoarthritic pain spend less time outdoors and thus have reduced opportunities for vitamin D synthesis. However, it is unlikely that experimental pain affected participants' vitamin D level, thus lending credence to our study model – namely, that vitamin D mediates the relationship between race and experimental pain. Lastly, although participants using regularly scheduled opioids were excluded from the study, and those using opioids as needed were asked to refrain from taking their medication two days prior to quantitative sensory testing, we did not account for other analgesic medication use, which may have affected the results of pain testing.

It is unclear why race differences in vitamin D level mediate group differences in experimental pain outcomes but do not mediate clinical osteoarthritic pain intensity, stiffness, or physical function on the WOMAC. This outcome may be related to the fact that osteoarthritic pain intensity measures were assessed retrospectively (i.e., pain over the past 48 hours) and therefore subject to recall bias. Alternately, vitamin D may influence certain aspects of pain processing reflected by pain thresholds, while osteoarthritic-related symptoms assessed by the WOMAC are likely driven by multiple factors over and above nociceptive processes. Moreover, a clinical threshold of vitamin D insufficiency may be necessary to better understand the relationship between lows levels of vitamin D, clinical knee pain, and total WOMAC score. In a systematic review of research on vitamin D and chronic pain, Straube and colleagues (16) did not find evidence to support a relationship between vitamin D and chronic pain. Results may have been impacted by methodological considerations, such as study design weakness and limited sample size. Similarly, in a review of seven studies, Straube and colleagues (14) found insufficient evidence to support treating chronic pain in ethnic minority patients by correcting vitamin D deficiency. However, none of the studies were randomized controlled trials and only two case studies investigated vitamin D supplementation. To strengthen these findings additional research is needed. High quality observational studies and randomized controlled trials with rigorous methodological control and adequate numbers of black participants are needed to understand the relationship between low levels of vitamin D, pain, and pain disparities experienced by black Americans. Improving vitamin D status is inexpensive and with low risk of adverse events. Thus, if additional research demonstrates improving vitamin D status lessens knee osteoarthritic pain, identifying and treating vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency may improve function for older adults with osteoarthritis, and reduce health disparities for black Americans.

Table 1.

Pearson's correlations

| Variables (N = 94) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age (years) | — | ||||||||||

| 2. BMI | .02 | — | |||||||||

| 3. Vitamin D | .02 | −.33** | — | ||||||||

| 4. CES-D | −.18 | −.01 | .07 | — | |||||||

| 5. WOMAC | .03 | .50** | −.27** | .28** | — | ||||||

| 6. Heat pain threshold, knee | −.02 | −.02 | .27** | .23* | −.12 | — | |||||

| 7. Heat pain tolerance, knee | −.11 | −.14 | .27** | .07 | −.22* | .61** | — | ||||

| 8. Heat pain threshold, forearm | −.07 | −.14 | .35** | .18 | −.15 | .58** | .59** | — | |||

| 9. Heat pain tolerance, forearm | −.16 | −.21* | .30** | .08 | −.20 | .47** | .88** | .64** | — | ||

| 10. Pressure pain, knee | −.07 | −.38** | .39** | .05 | −.41** | .37** | .36** | .37** | .35** | — | |

| 11. Pressure pain, forearm | −.19 | −.16 | .34** | .06 | −.22* | .36** | .35** | .41** | .37** | .67** | — |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the participants and staff of the Understanding Pain & Limitations in OsteoAthritic Disease (UPLOAD) study and the staff of the UF Clinical Research Center, without whom this research would not have been possible. Toni L. Glover is a John A. Hartford Foundation Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capacity (BAGNC) Scholar and a Mayday Fund grantee (AAN 11-116). Additional support provided by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (grant number AG033906) and the UF Clinical and Translational Science Institute (RR029890).

Toni L. Glover is a John A. Hartford Foundation Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capacity (BAGNC) Scholar and a Mayday Fund grantee (AAN 11-116). Additional supported provided by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (grant number AG033906) and the UF Clinical and Translational Science Institute (RR029890).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and all authors approved the final version. Toni Glover had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses.

Substudy conception and design. Glover, Horgas, Fillingim.

Acquisition of data. Glover, Goodin, Kindler, King, Sibille.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Glover, Goodin, Fillingim.

REFERENCES

- 1.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mason RS, Sequeira VB, Gordon-Thomson C. Vitamin D: the light side of sunshine. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(9):986–93. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holick MF, Chen TC. Vitamin D deficiency: a worldwide problem with health consequences. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(4):1080S–6S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.1080S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginde AA, Liu MC, Camargo CA., Jr. Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988–2004. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(6):626–32. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant WB, Peiris AN. Possible role of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in black-white health disparities in the United States. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11(9):617–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright NC, Chen L, Niu J, Neogi T, Javiad K, Nevitt MA, et al. Defining physiologically “normal” vitamin D in African Americans. Osteoporos Int. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1877-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson-Hughes B. Racial/ethnic considerations in making recommendations for vitamin D for adult and elderly men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(6 Suppl):1763S–6S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1763S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkins CH, Birge SJ, Sheline YI, Morris JC. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with worse cognitive performance and lower bone density in older African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(4):349–54. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30883-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris SS, Soteriades E, Coolidge JA, Mudgal S, Dawson-Hughes B. Vitamin D insufficiency and hyperparathyroidism in a low income, multiracial, elderly population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(11):4125–30. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.IOM . Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heaney RP, Holick MF. Why the IOM recommendations for vitamin D are deficient. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(3):455–7. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaganti RK, Parimi N, Cawthon P, Dam TL, Nevitt MC, Lane NE. Association of 25-hydroxyvitamin D with prevalent osteoarthritis of the hip in elderly men: the osteoporotic fractures in men study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(2):511–4. doi: 10.1002/art.27241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Straube S, Moore RA, Derry S, Hallier E, McQuay HJ. Vitamin d and chronic pain in immigrant and ethnic minority patients-investigation of the relationship and comparison with native Western populations. Int J Endocrinol. 2010;2010:753075. doi: 10.1155/2010/753075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atherton K, Berry DJ, Parsons T, Macfarlane GJ, Power C, Hypponen E. Vitamin D and chronic widespread pain in a white middle-aged British population: evidence from a cross-sectional population survey. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):817–22. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.090456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Straube S, Andrew Moore R, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Vitamin D and chronic pain. Pain. 2009;141(1–2):10–3. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAlindon TE, Felson DT, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, Aliabadi P, Weissman B, et al. Relation of dietary intake and serum levels of vitamin D to progression of osteoarthritis of the knee among participants in the Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(5):353–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-5-199609010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.IOM . Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wieland HA, Michaelis M, Kirschbaum BJ, Rudolphi KA. Osteoarthritis - an untreatable disease? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4(4):331–44. doi: 10.1038/nrd1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease C, Prevention Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence and impact of doctor-diagnosed arthritis--United States, 2002. MMWR. 2005;54(5):119–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter DJ, McDougall JJ, Keefe FJ. The symptoms of osteoarthritis and the genesis of pain. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34(3):623–43. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apkarian AV, Baliki MN, Geha PY. Towards a theory of chronic pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2009;87(2):81–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain. 2009;10(12):1187–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hadjistavropoulos T, Herr K, Turk DC, Fine PG, Dworkin RH, Helme R, et al. An interdisciplinary expert consensus statement on assessment of pain in older persons. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(1 Suppl):S1–43. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31802be869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, et al. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med. 2003;4(3):277–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards CL, Fillingim RB, Keefe F. Race, ethnicity and pain. Pain. 2001;94(2):133–7. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green CR, Hart-Johnson T. The impact of chronic pain on the health of black and white men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(4):321–31. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30604-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahim-Williams FB, Riley JL, 3rd, Herrera D, Campbell CM, Hastie BA, Fillingim RB. Ethnic identity predicts experimental pain sensitivity in African Americans and Hispanics. Pain. 2007;129(1–2):177–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in responses to multiple experimental pain stimuli. Pain. 2005;113(1–2):20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ames BN. Low micronutrient intake may accelerate the degenerative diseases of aging through allocation of scarce micronutrients by triage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(47):17589–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608757103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee YC, Lu B, Bathon JM, Haythornthwaite JA, Smith MT, Page GG, et al. Pain sensitivity and pain reactivity in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010 doi: 10.1002/acr.20373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heaney RP. Long-latency deficiency disease: insights from calcium and vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(5):912–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.5.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):1039–49. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale. APM. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Van Limbeek J, Braam AW, De Vries MZ, Van Tilburg W. Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D): results from a community-based sample of older subjects in The Netherlands. Psychol Med. 1997;27(1):231–5. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796003510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Theiler R, Spielberger J, Bischoff HA, Bellamy N, Huber J, Kroesen S. Clinical evaluation of the WOMAC 3.0 OA Index in numeric rating scale format using a computerized touch screen version. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;10(6):479–81. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76(4):408–20. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–91. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6)::1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fritz MS, Taylor AB, MacKinnon DP. Explanation of Two Anomalous Results in Statistical Mediation Analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2012;47(1):61–87. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2012.640596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hastie BA, Riley JL, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences and responses to pain in healthy young adults. Pain Med. 2005;6(1):61–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roesel TR. Does the central nervous system play a role in vitamin D deficiency-related chronic pain? Pain. 2009;143(1–2):159–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tague SE, Clarke GL, Winter MK, McCarson KE, Wright DE, Smith PG. Vitamin d deficiency promotes skeletal muscle hypersensitivity and sensory hyperinnervation. J Neurosci. 2011;31(39):13728–38. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3637-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCann JC, Ames BN. Is there convincing biological or behavioral evidence linking vitamin D deficiency to brain dysfunction? FASEB J. 2008;22(4):982–1001. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9326rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen US, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Niu J, Zhang B, Felson DT. Increasing prevalence of knee pain and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: survey and cohort data. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(11):725–32. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoang MT, Defina LF, Willis BL, Leonard DS, Weiner MF, Brown ES. Association between low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and depression in a large sample of healthy adults: the Cooper Center longitudinal study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(11):1050–5. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lansdowne AT, Provost SC. Vitamin D3 enhances mood in healthy subjects during winter. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;135(4):319–23. doi: 10.1007/s002130050517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buell JS, Dawson-Hughes B. Vitamin D and neurocognitive dysfunction: preventing “D”ecline? Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29(6):415–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melzack R. From the gate to the neuromatrix. Pain. 1999;(Suppl 6):S121–6. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]