Abstract

BACKGROUND

Previous research has demonstrated that depression and family history of illicit substance use disorders (ISUDs) are risk factors for the development of ISUDs. However, no study to date has examined whether these risk factors interact to predict onset. In addition, history of parental and sibling ISUDs have been identified as risk factors almost exclusively in healthy individuals and thus, it is unknown whether they confer unique risk among adolescents with a history of depression.

METHODS

The current study examined these questions using data from the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (OADP). DSM diagnoses of probands were assessed during 4-waves, first in adolescence (ages 14–18) and subsequently up until age 30. Lifetime DSM diagnoses of ISUDs in biological mothers, fathers, and siblings were obtained.

RESULTS

Proportional hazards model analyses indicated that there was a significant depression by parental ISUDs interaction. Among probands with parental ISUDs (and not among those without parental ISUDs), depression in adolescence was significantly associated with a shorter time to develop an ISUD. Sibling ISUDs were not associated with onset and did not interact with adolescent depression.

CONCLUSION

Prevention and intervention efforts targeted at this particularly at-risk group may be effective.

Keywords: illicit substance use disorder, major depressive disorder, family history

1. INTRODUCTION

The use of illicit substances including opioids, stimulants, hallucinogens, and inhalants is associated with numerous adverse consequences. For example, illicit substance use has been associated with premature mortality, homicide, violence, HIV infection, and increased rates of mental illness (Frank, 2000; Gossop et al., 2002; Hser et al., 2001). In addition, over 193 billion dollars are spent annually on substance abuse related costs including disability, welfare, and crime (U.S. Department of Justice, 2011). As such, identifying at risk populations for illicit substance use is critical for the development of effective interventions.

Empirical evidence suggests that depression increases the risk for the development of illicit substance use disorders (ISUDs; Abraham and Fava, 1999; Boscarino et al., 2010, Newcomb and Bentler, 1989). For example, a 10-year longitudinal study, utilizing a large community sample, found that adolescent depression was significantly associated with higher rates of illicit substance use in adulthood (Lansford et al., 2008). A history of depression has also been shown to predict frequent illicit drug use (Sihvola et al., 2008) and risk for opioid and cocaine dependence (Abraham and Fava, 1999; Boscarino et al., 2010). Similarly, drug users often report using illicit substances in response to depressive symptoms (Weiss et al., 1992) and depressed mood has been shown to increase drug cravings in abstinent users (Childress et al., 1994). Thus, depression appears to be an important factor underlying the motivation to use illicit drugs and escalation to abuse and dependence.

The link between depression and ISUDs is consistent with both negative reinforcement models of addiction (Baker et al., 2004) and the self-medication hypothesis (Hesselbrock and Hesselbrock, 1997; Khantzian, 1985). Although these theories are independent, they both posit that engagement in substance use brings perceived and/or real relief from negative affective states (such as depression), thereby negatively reinforcing this behavior and increasing the likelihood of using drugs in the future. Further, these theories postulate that over time the use of substances as a coping mechanism leads to an increased risk of abuse and dependence (Cooper et al., 1992; Laurent et al., 1997).

Although an association between depression and ISUDs has been well established, there have been notable inconsistencies within the literature. While some studies suggest that depression increases the risk for illicit substance abuse or dependence (e.g., Boscarino et al., 2010), others have failed to find this association (Clark et al., 1999; Windle and Wiesner, 2004) or have found that illicit substance use more often precedes the onset of depression (Bovasso, 2001; Brook et al., 1998; Rao et al., 2000). Although there are several potential explanations for these inconsistencies (see Swendsen and Merikangas, 2000), the relationship between depression and illicit substance use is likely to be highly complex and there may be important moderators influencing the developmental pathway between these disorders.

One potential moderating factor in this trajectory may be family history of ISUDs. Notably, having parents and/or siblings with an ISUD has been shown to be one of the most robust predictors of proband ISUDs. For instance, a recent 25-year longitudinal study found that parental illicit drug use significantly predicted ISUDs in offspring ages 16–25 (Fergusson et al., 2008). Similar findings have been reported by others (Brook et al., 1990; Clark et al., 2005; Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Kirisci et al., 2005; Reinherz et al., 2000). Additionally, many studies have demonstrated that illicit substance use in siblings (particularly older siblings) predicts onset of proband ISUDs (Bahr et al., 2005; Duncan et al., 1996; Windle, 2000). Of note, when parental and sibling influences on drug use have been compared, it appears that each factor connotes unique risk (Duncan et al., 1996; Needle et al., 1986; Windle, 2000).

Evidence indicates that family history of ISUDs influences proband onset via both genetic and environmental factors (Kendler et al., 2000; Tsuang et al., 1996). In addition, there appear to be important differences in the mechanisms associated with parental and sibling ISUDs. For instance, it has been demonstrated that disrupted family cohesion (Hoffmann and Cerbone, 2002), exposure to stressful life events (e.g., financial instability, violence; Hoffmann et al., 2000), and poor parenting practices (Ammerman et al., 1999) are all potential mechanisms underlying the relationship between parental and proband ISUDs. Siblings, on the other hand, appear to connote risk through social learning and drug advocacy. More specifically, siblings with ISUDs may act as models for drug use and foster favorable attitudes and beliefs about substance use (Brook et al., 1990; Buhrmester, 1992; Needle et al., 1986). In addition, they may serve as sources for obtaining illicit substances (Clayton and Lacy, 1982; Denton and Kampfe, 1994) and may facilitate contact with substance using peers (Conger and Reuter, 1996). Taken together, parental and sibling history of ISUDs are both robust predictors of proband onset but appear to be separable risk factors.

Given the inconsistent findings on whether depression predicts the onset of ISUDs and the robustness of family history as a predictor of onset, it is possible that a family history of ISUDs will moderate the effect of depression on onset. Specifically, depression may predict the development of ISUDs only among those with a family (i.e., parental and/or sibling) history of ISUDs. To our knowledge, no study to date has examined this question, a notable omission given the need to identify risk factors for ISUDs. Further, family history of ISUDs has been identified as a risk factor for onset almost exclusively in healthy individuals. Thus, the influence of family history on adolescents with depression is still unknown.

We will examine this question using data from the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (OADP; Lewinsohn et al., 1993), an extensive 4-wave longitudinal investigation of adolescent and adult psychopathology. As part of the study, DSM diagnoses were assessed during adolescence and subsequently up until age 30. In addition, lifetime DSM diagnoses of biological mothers, fathers, and all siblings were obtained.

Data from the OADP is particularly well-suited for the current study aims for numerous reasons. First, although there have been several prospective studies examining the development of ISUDs (e.g., Fergusson et al., 2008), they have had relatively short follow-up periods and have not assessed individuals past emerging adulthood (i.e., early twenties). Although the average age of onset for drug abuse and dependence is approximately 21 years (Compton et al., 2007), onset can occur at any time and late onset individuals have generally been excluded from existing longitudinal data. Because individuals in the OADP were assessed up until age 30, the current study will address this gap within the literature and examine onset into early adulthood. Second, a disproportionate number of studies have examined the etiology of licit substance use disorders (e.g., alcohol) or substance use more broadly (Sher et al., 2005; Sung et al., 2004). Our data, however, allow us to specifically examine onset of ISUDs and thus, advance understanding of the developmental pathways uniquely associated with these disorders. Lastly, as was previously mentioned, the literature suggests that parental and sibling drug use may confer unique risk (Windle, 2000). Using data from the OADP, we can formally test this assumption by including both sibling ISUDs and parental ISUDs into one model. In addition, we are able to examine them as separate moderators of outcome.

2. Method

2.1 Probands and Procedure

The current study examined data from the OADP which was collected from 1987 to 2004 (Lewinsohn et al., 1993). Detailed descriptions of recruitment procedures, participation rates, and sample characteristics have been previously reported (Lewinsohn et al., 1993, 2003; Rohde et al., 2007).

Adolescents (ages 14–18) were randomly selected from nine senior high schools in western Oregon. The sample included 1709 adolescents (mean age 16.6 years; SD = 1.2) and initial assessments (T1) took place between 1987 and 1989. Approximately one year later (M = 13.8 months, SD = 2.3), 1507 of the original probands (88.2%) completed the second assessment (T2). There were few differences between participants and non-participants at T1 and T2 (see Lewinsohn et al., 1993 for a full description).

At age 24 years, all adolescents with a history of a psychopathology by T2 (n = 644) and a random sample of adolescents with no history of psychopathology by T2 (n = 457) were invited to participate in a third (T3) evaluation. All non-white participants were also invited to complete the T3 assessment to maximize ethnic diversity. A total of 941 (85%) of the invited participants completed the T3 assessment and there were no diagnostic differences between those who did and did not complete the assessment.

As part of the T3 assessment, lifetime psychopathology in the first-degree relatives of the probands was assessed. Direct diagnostic interviews were conducted with all available relatives and informant data was provided by the probands to supplement the interviews. When relatives were unable to complete the direct interview, informant data from the proband and a second informant (e.g., co-parent or sibling ≥ 18) were collected.

All T3 probands were invited to participate in a fourth evaluation (T4) at approximately age 30. A total of 816 (87% of T3 participants) completed the T4 assessment. Differences between participants and non-participants at T3 and T4 were small (see Olino et al., 2008).

Within the current study, probands were excluded if they were missing diagnostic information on their biological parents (n = 101) or had a lifetime diagnosis of a psychotic disorder and/or bipolar spectrum disorder (n = 33). Additionally, we excluded individuals with a T1 diagnosis of an ISUD (n = 29) so that our dependent variable represented first onset of an ISUD. Thus, our final sample included 778 probands.

2.2 Diagnostic Assessment of Probands

Proband psychopathology was assessed directly at T1 and T2 and by telephone at T3 and T4. It has previously been demonstrated that phone interviews and face-to-face interviews yield high inter-method reliability for diagnoses and symptoms (see Rohde et al., 1997 for a full description; Sobin et al., 1993). At T1, the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS; Orvaschel et al., 1982) was used to assess current and lifetime diagnoses. The interview included features of the Epidemiologic (Orvaschel et al., 1982) and Present Episodes (Chambers et al., 1985) versions and additional items which were used to derive DSM-III-R diagnoses (American Psychiatric Association, 1987). At the T2 and T3 evaluations, participants were interviewed using both the K-SADS and the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE; Keller et al., 1987). At T4, participants were administered the LIFE interview and the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis-I DSM-IV Disorders Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP; First et al., 1994). Diagnoses were made according to DSM-III-R criteria (APA, 1987) for T1 and T2 and according to DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994) for T3 and T4. A detailed description of the differences in diagnostic criteria of substance abuse and dependence between the DSM-III-R and the DSM-IV is described in Schuckit et al., (1994). Most notably, in the DSM-IV, criterion A symptoms are required to cluster within a single year and physiological symptoms of dependence (i.e., tolerance and/or withdrawal) are a subtype.

All interviewers were trained in the use of each diagnostic measure and completed a minimum of two supervised training interviews in which they achieved a kappa greater than .80 for agreement between their symptom ratings and those of their supervisor. Most interviewers had advanced degrees in clinical or counseling psychology or social work, and several years of clinical experience. The inter-rater reliability of lifetime diagnoses for MDD and ISUDs have been previously reported to be good to excellent (Lewinsohn et al., 1993; Rohde et al., 2007).

2.3 Diagnostic Assessment of Biological Relatives

Biological first-degree relatives were interviewed using the SCID-NP. In addition, family history data for each relative was collected by probands using the Family Informant Schedule and Criteria (FISC; Mannuzza and Fyer, 1990), with additional items included to derive DSM-IV diagnoses. If a relative was unable to complete the SCID-NP, an additional family member was asked to provide informant data using the FISC. Detailed information on the sensitivity and specificity of informants' reports has been reported elsewhere (see Klein et al., 2005).

Given the multiple sources of family diagnostic information, lifetime DSM-IV diagnoses were derived using the `best-estimate' procedure (Leckman et al., 1982). Using the published guidelines by Klein et al. (1994), two senior clinicians (out of a team of 4) independently reviewed all SCID-NP and FISC information and made best-estimate diagnoses for each relative. If there was disagreement between the two clinicians, the diagnosis was made by consensus. The definition of ISUDs in the current study was the same for probands and relatives.

All relatives with available diagnostic information were included in the current study regardless of lifetime diagnoses. Our final sample of relatives consisted of 1542 parents (50.5% mothers) and 1001 siblings (49.5% sisters). On average, probands had 1.29 (SD = 1.11) siblings. Direct interviews were obtained from 74.8% of the mothers, 45.9% of the fathers, and 68.3% of the siblings. At T3, the average age for mothers and fathers was 49.10 (SD = 5.18) and 50.93 (SD = 6.67), respectively. The average age of all siblings at T3 was 23.53 (SD = 6.31). Of the mothers, 94.2% reported graduating high school and 28.6% received a college degree (i.e., BA or BS) or higher. Of the fathers, 95.6% graduated high school while 42.4% had a college degree or higher.

2.4 Data Analysis Plan

Within the current study, ISUDs were classified as any of the following: amphetamine abuse or dependence, opioid abuse or dependence, cocaine abuse or dependence, hallucinogen/PCP abuse or dependence, sedative abuse or dependence, inhalant abuse or dependence, and polydrug dependence. We chose to exclude probands who exclusively developed a cannabis use disorder from our dependent variable to more accurately identify individuals at risk for “hard drug use disorders.” However, it is important to note that T1 lifetime diagnoses of cannabis abuse and dependence were controlled for in our analyses since it has been demonstrated that adolescent cannabis use increases the risk for harder substances in adulthood (Fergusson et al., 2006; Lessem et al., 2006). If individuals developed more than one ISUD between T1 and T4, age of onset was coded as the earliest diagnosis.

Adolescent depression was coded as past or current (through T1) diagnosis of MDD (yes/no). Parental history of ISUDs was coded as lifetime diagnosis of an ISUD in either parent. Sibling history of ISUDs was coded similarly.

We examined the unique and interactive effects of MDD at T1 and family history of ISUDs on the development of proband ISUDs using Cox proportional hazards (PH) models. We conducted separate Cox models to examine the moderating effects of parental and sibling ISUDs. Probands who did not have a biological sibling (n = 168) were excluded from the sibling models. Thus, the sample sizes of the two models vary slightly. The time-to-event variable was time (in years) from the T1 assessment that the probands first developed an ISUD and time of last assessment for individuals who did not develop an ISUD (i.e., censored observations). Time-to-event analyses are more powerful than analytic strategies which only examine the proportion of individuals who experienced an event at a single time point. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by including a Time by Predictor interaction term in each Cox model (Singer and Willett, 1991). In all models, the interaction term was not significant (p's > .29) and thus, the proportional hazard assumption was met and the interaction term was removed from the models.

Theoretically relevant covariates included in parental and sibling models were proband gender, lifetime proband diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence through T1 (n = 30), lifetime proband diagnosis of cannabis abuse or dependence through T1 (n = 33), intactness of the home (i.e., whether or not the proband was living with both biological parents at T1), and proportion of relatives (parents or siblings for the respective models) who received a direct interview.

As was previously mentioned, all participants with a history of psychopathology through T2 and all non-white participants were selected for the T3 and T4 assessments. Therefore, all analyses weighted each proband based on their probability of being invited to participate in T3. All models were conducted using SUDAAN 8.0.3 (Shah et al., 1997).

Variables were entered into the Cox models simultaneously to examine the adjusted effects of MDD at T1 and parental/sibling ISUDs on the onset of proband ISUDs. In addition to our primary analyses, we also ran a PH model that included both parental and sibling history of ISUDs to attempt to replicate previous findings suggesting that each are unique risk factors (e.g., Windle, 2000).

3. Results

3.1 Proband Diagnoses

At T1, 186 (23.9%) probands had a lifetime diagnosis of MDD. During T2–T4, 77 (9.9%) probands developed at least one ISUD. Average age of onset for an ISUD was 20.29 years of age (SD = 3.59). Substance use disorders developed during T2–T4 for those with and without a lifetime diagnosis of MDD at T1 are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Proband substance use disorders developed between T2–T4 for those with and without a lifetime diagnosis of depression at T1

| Drag Use Disorder | No MDD at T1 | Yes MDD at T1 |

|---|---|---|

| Cocaine Dependence/Abuse | 2.5% | 2.7% |

| Hallucinogen Dependence/Abuse | 3.0% | 2.7% |

| Inhalant Dependence/Abuse | 0.3% | 0.0% |

| Opioid Dependence/Abuse | 1.0% | 1.6% |

| Amphetamine Dependence/Abuse | 6.3% | 9.2% |

| Sedative Dependence/Abuse | 0.7% | 0.0% |

| Polydrug Dependence | 0.5% | 1.1% |

Note. Diagnoses are displayed as percent of probands with a lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) at T1 (N = 186) and percent of probands without a lifetime diagnosis of MDD at T1 (N= 592).

3.2 Parent and Sibling Substance Use Disorders

Of the 778 probands included in the current study, 125 (16.1%) had at least one parent (61 mothers and 73 fathers) and 95 (12.2%) had at least one sibling with a lifetime diagnosis of an ISUD. Detailed lifetime substance use diagnoses for mothers, fathers, and siblings are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Lifetime diagnoses of substance use disorders among mothers, fathers, and siblings

| Drag Use Disorder | Mothers | Fathers | Siblings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cocaine Dependence/Abuse | 0.8% | 1.9% | 2.8% |

| Hallucinogen Dependence/Abuse | 0.9% | 1.8% | 4.1% |

| Inhalant Dependence/Abuse | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| Opioid Dependence/Abuse | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.6% |

| Amphetamine Dependence/Abuse | 4.4% | 4.8% | 6.9% |

| Sedative Dependence/Abuse | 1.8% | 1.3% | 1.1% |

| Polydrug Dependence | 0.8% | 2.1% | 1.3% |

| “Other” Drug Dependence | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.4% |

Note. Diagnoses are displayed as percent of mothers (N = 778), fathers (N = 764), and siblings (N = 1001) that met criteria for a DSM-IV lifetime diagnosis.

3.3 MDD by Parental Drug Use Disorders

Results indicated that several covariates were associated with a shorter time to develop an ISUD in probands; specifically, a T1 lifetime diagnosis of cannabis abuse/dependence, a T1 lifetime diagnosis of alcohol abuse/dependence, and not living with both biological parents at T1 (see Table 3). Most notably, over and above these factors, the interaction of MDD at T1 by parental ISUDs was significant (HR = 3.18, 95% CI = 1.02 – 9.93, p < .05). (We conducted two additional PH models to examine the interactive effects of MDD at T1 and parental ISUDs without the inclusion of covariates. First, we included only the main effects and found that both MDD at T1 (HR = 1.70, 95% CI = 1.04 – 2.78, p < .05) and parental history of ISUDs (HR = 1.79, 95% CI = 1.03 – 3.10, p < .05) were associated with shorter time to develop ISUDs in probands. We also ran a model that included MDD at T1, parental ISUDs, and the interaction of these two variables (and also no covariates). The interaction was a trend in the predicted direction (HR = 2.81, 95% CI = 0.93 – 8.46, p = .066), suggesting that demographic and other important covariates reduced unexplained variance and subsequently increased the power to detect significant effects.)

Table 3.

Results from the proportional hazards model examining unique and interactive effects of MDD at T1 and parental/sibling ISUDs on time to develop an ISUD

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Model | |||

| T1 MDD | 0.91 | 0.46–1.79 | 0.78 |

| Parent Illicit Drags | 1.10 | 0.49–2.47 | 0.82 |

| T1 Cannabis** | 5.31 | 2.42–11.66 | 0.00 |

| T1 Alcohol* | 2.43 | 1.00–5.86 | 0.05 |

| Intactness of Home* | 0.55 | 0.32–0.97 | 0.04 |

| Parent Direct Interview Density | 0.86 | 0.42–1.80 | 0.69 |

| Gender | 1.09 | 0.68–1.76 | 0.72 |

| T1 MDD × Parent Illicit Drugs* | 3.18 | 1.02–9.93 | 0.05 |

| Sibling Model | |||

| T1 MDD | 1.50 | 0.64–3.49 | 0.35 |

| Sibling Illicit Drugs | 1.95 | 0.80–4.77 | 0.14 |

| T1 Cannabis | 2.45 | 0.62–9.74 | 0.20 |

| T1 Alcohol** | 4.49 | 1.52–16.01 | 0.01 |

| Intactness of Home | 0.88 | 0.45–1.72 | 0.71 |

| Sibling Direct Interview Density | 0.55 | 0.24–1.23 | 0.14 |

| Gender | 1.72 | 0.93–3.19 | 0.09 |

| T1 MDD × Sibling Illicit Drugs | 1.50 | 0.40–5.73 | 0.55 |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .05.

Parent Illicit Drugs = parental history of ISUDs dichotomized as no lifetime diagnosis of an ISUD or history of any ISUD (in either parent); Sibling Illicit Drugs = sibling history of ISUDs dichotomized as no lifetime diagnosis of an ISUD or history of any ISUD (in any sibling); T1 MDD, T1 Cannabis, and T1 Alcohol = lifetime diagnosis at the T1 assessment.

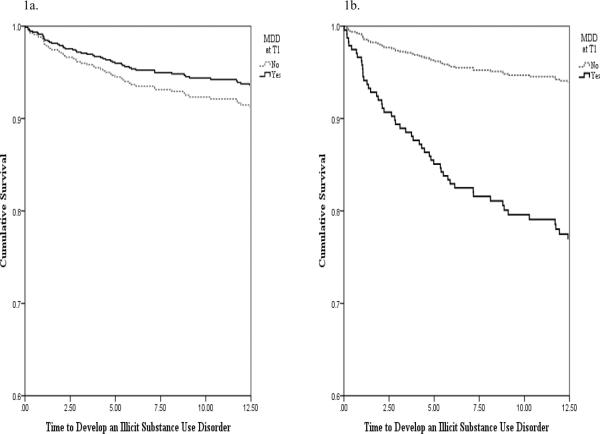

To follow-up the significant interaction, we conducted two additional PH models, one for probands with a parental history of an ISUD and one for probands without. All of the aforementioned covariates were included in the models. For probands without a parental history, MDD at T1 was not significantly associated with time to develop an ISUD (HR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.41 – 1.49, p > .05; see Figure 1a). However, for those with a parental history, MDD at T1 significantly predicted time to develop an ISUD (HR = 2.90, 95% CI = 1.15 – 7.35, p < .05; see Figure 1b). (In order to argue more strongly for the directionality between parental and proband ISUDs we calculated year of onset for both parents and probands to determine whether parental ISUDs preceded proband ISUDs. Our results indicated that 88% of parents developed the substance use disorder first. On average, parents developed the ISUD 20 years prior to the onset of the probands' ISUD.)

Figure 1.

Survival hazards plot of the relationship between MDD and time to develop an ISUD for individuals without a history of parental ISUDs (1a) and for individuals with a history of parental ISUDs (1b)

Among probands who had parental ISUDs, the average time to develop their own ISUD was 1.81 years from baseline (for those with MDD) and 5.61 years (for those without MDD). Among probands who had no parental ISUDs, the average time to develop their own ISUD was 5.38 years from baseline (for those with and MDD) and 4.31 years (for those without MDD).

3.4 MDD by Sibling Drug Use Disorders

Results indicated that a T1 lifetime diagnosis of alcohol abuse/dependence was associated with shorter time to develop an ISUD (see Table 3). Most importantly, there was no significant MDD at T1 by sibling history of ISUD interaction. (When only the main effects were included in the model (and no covariates), MDD at T1 (HR = 1.99, 95% CI = 1.06 – 3.74, p < .05) was significantly associated with shorter time to develop ISUDs in probands. The main effect for sibling ISUDs was a trend in the predicted direction (HR = 1.83, 95% CI = 0.93 – 3.59, p = .08). When the interaction was included, results indicated that there was no significant MDD at T1 by sibling ISUDs interaction.)

3.5 Parent versus Sibling Risk

First, we ran one model that included only parental history of ISUDs and sibling history of ISUDs to examine the effects of one while controlling for the other. Results indicated that parental history, but not sibling history, was significantly associated with shorter time to develop an ISUD in probands (HR = 1.79, 95% CI = 1.01 – 3.18, p < .05). Next, we added sibling history of ISUDs and proportion of siblings who received a direct interview into our larger parental model (discussed in section 3.3) to determine whether any significant findings remained when controlling for sibling history of ISUDs. Results indicated that a T1 lifetime diagnosis of both alcohol and cannabis abuse/dependence and not living with both biological parents at T1 were still associated with earlier onset (see Table 4). Notably, results also revealed that there was still a significant MDD at T1 by parental history of ISUDs interaction (HR = 3.09, 95% CI = 0.99 – 9.64, p = .05).

Table 4.

Results from the proportional hazards models examining the unique risk associated with parental and sibling history of ISUDs

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Block One | |||

| Sibling Illicit Drugs | 1.15 | 0.60–2.20 | 0.68 |

| Parent Illicit Drugs* | 1.79 | 1.01–3.18 | 0.05 |

| Block Two | |||

| T1 MDD | 0.91 | 0.46–1.80 | 0.78 |

| Sibling Illicit Drugs | 1.24 | 0.65–2.38 | 0.51 |

| Parent Illicit Drugs | 1.09 | 0.48–2.46 | 0.84 |

| T1 Cannabis** | 5.39 | 2.50–11.63 | 0.00 |

| T1 Alcohol* | 2.47 | 1.03–5.90 | 0.04 |

| Intactness of Home* | 0.56 | 0.32–0.98 | 0.04 |

| Parent Direct Interview Density | 0.83 | 0.39–1.74 | 0.62 |

| Sibling Direct Interview Density | 1.7 | 0.54–2.13 | 0.84 |

| Gender | 1.09 | 0.67–1.76 | 0.73 |

| T1 MDD × Parent Illicit Drugs* | 3.09 | 0.99–9.64 | 0.05 |

Note.

p < .01;

p < .05.

Parent Illicit Drugs = parental history of ISUDs dichotomized as no lifetime diagnosis of an ISUD or history of any ISUD (in either parent); Sibling Illicit Drugs = sibling history of ISUDs dichotomized as no lifetime diagnosis of an ISUD or history of any ISUD (in any sibling); T1 MDD, T1 Cannabis, and T1 Alcohol = lifetime diagnosis at the T1 assessment.

4. Discussion

Although it has been demonstrated that depression in adolescence is associated with the development of ISUDs in adulthood (e.g., Boscarino et al., 2010), there have been several studies that have failed to find this association (Clark et al., 1999; Windle and Wiesner, 2004). This suggests that there may be important moderators influencing this relationship. As such, the aim of the current study was to examine whether MDD in adolescence interacts with parental and/or sibling history of ISUDs to predict the onset of ISUDs. Results indicated that there was a significant MDD by parental history of ISUDs interaction. Specifically, among those with a parental history of ISUDs (and not among those without a parental history), MDD at T1 was significantly associated with a shorter time to develop an ISUD. Results also suggested that this relationship was specific to parental history given that there was no significant interaction between MDD at T1 and sibling history of ISUDs.

Results revealed that there were no significant direct effects for depression, parental history of ISUDs, and sibling history of ISUDs, which is inconsistent with prior investigations (Bahr et al., 2005; Boscarino et al., 2010; Fergusson et al., 2008). However, it appears that these effects may be accounted for by the other risk factors (i.e., covariates) included in the current study. For example, when only MDD at T1 and parental history of ISUDs were entered into the model (and no covariates), there were significant direct effects for both predictors (see footnote #1). However, when covariates were included, these direct effects became non-significant. This suggests that these factors may not be robust independent predictors of the development of ISUDs; especially when accounting for factors such as a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol or cannabis abuse/dependence. In line with the current findings, it appears to be important to consider how these risk factors interact and how the presence of more than one risk factor may place individuals at the greatest risk for harmful patterns of illicit drug use.

There are several potential explanations as to why those with depression in adolescence and a parental history of ISUDs evidenced the greatest risk for the development of ISUDs. First, it is possible that all probands with a parental history of ISUDs were more likely to engage in recreational drug use due to factors such as genetic vulnerability (McGue et al., 2000), poor parental attachment (Flores, 2001; Howe et al., 1999), lower levels of parental monitoring (Duncan et al., 1998; Kandel, 1990), and greater exposure to violence and childhood maltreatment (Walsh et al., 2003). However, within this at-risk group, individuals with depression may be more likely to continue using illicit drugs past adolescence and subsequently develop an ISUD in adulthood. One plausible mechanism for this effect is that adolescents with depression experience a temporary reduction of negative affect (i.e., depressive symptoms) in response to drug use which serves to reinforce drug taking behaviors and increase the likelihood of using drugs in the future (Baker et al., 2004; Eissenberg, 2004). In contrast, the at-risk adolescents without depression may engage in recreational drug use but fail to escalate to drug abuse/dependence due to the absence of negative reinforcement processes. Thus, the group at the greatest risk for ISUDs may be those who experience parental/environmental factors associated with drug use and benefit from the negatively reinforcing properties of an illicit substance.

An alternative explanation is that although early-onset depression places individuals at risk, those without a parental history of ISUDs may have access to certain protective or resiliency factors that buffer against the onset of drug abuse and dependence. For instance, depressed adolescents without a history of parental ISUDs may have higher levels of parental attachment and monitoring, greater family cohesion, and increased financial and environmental stability which serve to alter their risk for ISUDs in adulthood (Brook et al., 2001; Duncan et al., 1998; Walden et al., 2004; Wills et al., 1992). These resources may provide adaptive alternatives to drug use to regulate their depressive symptoms (e.g., pharmacotherapy, familial support). However, the disrupted family cohesion and poor parenting practices associated with parental illicit drug use may result in a limited repertoire of coping strategies to manage depressed mood among individuals with parental ISUDs. More specifically, these adolescents may feel isolated, lack familial and social support, and have little financial resources to seek treatment, which serve to maintain their depressed mood. Therefore, having parents without a history of ISUDs may lead to adaptive skills to relieve depressive symptoms while having parents with ISUDs may lead to limited resources (with the exception of illicit drugs) to ameliorate their negative affect.

Interestingly, within the current study, we were able to directly test whether parents and siblings confer unique risk for the development of ISUDs in probands. When both factors were included in one model, parental, but not sibling history of ISUDs was associated with shorter time to develop an ISUD in probands. Markedly, however, both effects were no longer significant when covariates were included. This suggests that neither parental nor sibling ISUDs may be robust (or at least independent) predictors of risk. While these results differ from others that have demonstrated that sibling ISUDs are a greater risk factor than parental ISUDs (e.g., Windle, 2000), they do support studies that have shown that parental and sibling history of ISUDs confer risk via different pathways.

Given that our findings indicated that parental history of ISUDs, but not sibling history of ISUDs, interacted with MDD at T1, the current study also highlights that these mechanisms may differ depending whether or not the proband has a history of depression. Importantly, our findings suggest that parental ISUDs may have a greater influence on risk than sibling ISUDs, among adolescents with a lifetime diagnosis of depression. Even when sibling history of ISUDs was controlled for in the parent models, the interaction remained significant demonstrating that there is unique risk in having both a parental history of ISUDs and a lifetime diagnosis of MDD in adolescence. Although highly speculative, it is possible because of their depressive symptoms, depressed adolescents spend more time with their parents and/or have disrupted sibling relationships, a process which results in greater parental versus sibling influence. Notably, future research is needed to examine these potential mechanisms and identify mediating factors between depression in adolescence and onset of ISUDs.

Although these findings address important gaps within the literature, there are several limitations of note. First, participants in the current study were exclusively recruited from urban and rural areas of western Oregon. Thus, participants‟ geographic location may have influenced accessibility to certain illicit drugs and may potentially limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, not all parents and siblings were directly interviewed which may have resulted in lower sensitivity for familial history of ISUDs. However, the percentage of both parents and siblings who received a direct interview was controlled for in our analyses. Third, the ISUDs (i.e., cocaine, heroin, etc.) examined in this study may have different developmental pathways but due to small sample sizes, we were not able to examine classes of ISUDs separately. Lastly, our study only included full-biological parents and siblings. As such, future research is needed to examine whether similar findings apply to step-parents and step-siblings.

With these limitations in mind, there are several important implications of these findings. First, the results from the current study help to clarify the relationship between depression in adolescence and the development of ISUDs in adulthood. Although depression in adolescence and familial history of ISUDs are often considered independent risk factors, our findings suggest that each factor may not be robustly (or at least independently) associated with onset. However, those with a history of depression in adolescence and a parental history ISUDs, appear to be at the greatest risk. Thus, both prevention and intervention efforts targeted at this particularly at-risk group may be effective. Moreover, these findings highlight the continued need for research examining the mechanisms underlying the relationships between adolescent depression, parental ISUDs, and the subsequent development of ISUDs.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source Funding for this study was provided by NIMH Grant MH40501 and MH50522 awarded to Peter Lewinsohn; the NIMH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors Peter Lewinsohn was the principal investigator of the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project. John Seeley contributed to the design of the study and was involved in the collection and management of data. Stewart Shankman provided assistance with statistical analyses and made important contributions to the editing of the manuscript. Stephanie Gorka developed the rationale for the paper, conducted the statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Abraham HD, Fava M. Order of onset of substance abuse and depression in a sample of depressed outpatients. Compr. Psychiatry. 1999;40:44–50. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd Ed., Rev. APA; Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Ed. APA; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman R, Kolko D, Kirisci L, Blackson T, Dawes M. Child abuse potential in parents with histories of substance use disorder. Child Abuse Negl. 1999;23:1225–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr SJ, Hoffmann JP, Yang X. Parental and peer influences on the risk of adolescent drug use. J. Prim. Prev. 2005;26:529–51. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychol. Rev. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA, Rukstalis M, Hoffman SN, Han JJ, Erlich PM, Gerhard GS, Stewart WF. Risk factors for drug dependence among out-patients on opioid therapy in a large US health-care system. Addiction. 2010;105:1776–1782. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovasso GB. Cannabis abuse as a risk factor for depression. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158:2033–2037. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, De La Rosa M, Whiteman M, Johnson E, Montoya I. Adolescent illegal drug use: the impact of personality, family, and environmental factors. J. Behav. Med. 2001;24:183–203. doi: 10.1023/a:1010714715534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Cohen P, Brook DW. Longitudinal study of co-occurring psychiatric disorders and substance use. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1998;37:322–330. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199803000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Gordon AS, Brook DW. The role of older brothers in younger brothers' drug use viewed in the context of parent and peer influences. J. Genet. Psychol. 1990;151:59–75. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1990.9914644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D. The developmental courses of sibling and peer relationships. In: Boer F, Dunn J, editors. Children's Sibling Relationships: Developmental and Clinical Issues. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers WJ, Puig-Antich J, Hirsch M, Paez P, Ambrosini PJ, Tabrizi MA, Davies M. The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interview: testretest reliability of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present Episode Version. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1985;42:696–702. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300064008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress AR, Ehrman R, McLellan A, MacRae J, Natalie M, O'Brien C. Can induced moods trigger drug-related responses in opiate abuse patients. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1994;11:17–23. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D, Cornelius J, Kirisci L, Tarter R. Childhood risk categories for adolescent substance involvement: a general liability typology. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Parker AM, Lynch KG. Psychopathology and substance-related problems during early adolescence: a survival analysis. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1999;28:333–341. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton RR, Lacy WB. Interpersonal influences of male drug use and drug use intentions. Int. J. Addict. 1982;17:655–666. doi: 10.3109/10826088209053009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2007;64:566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Rueter MA. Siblings, parents, and peers: a longitudinal study of social influences in adolescent risk for alcohol use and abuse. In: Brody GH, editor. Sibling Relationships: Their Causes and Consequences. Ablex; Stamford, CT: 1996. pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Windle M. Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychol. Assess. 1992;4:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Denton RE, Kampfe CM. The relationship between family variables and adolescent substance abuse: a literature review. Adolescence. 1994;29:475–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Biglan A, Ary D. Contributions of the social context to the development of adolescent substance use: a multivariate latent growth modeling approach. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50:57–71. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Hops H. The role of parents and older siblings in predicting adolescent substance use: modeling development via structural equation latent growth methodology. J. Fam. Psychol. 1996;10:158–172. [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg T. Measuring the emergence of tobacco dependence: the contribution of negative reinforcement models. Addiction. 2004;99(Suppl. 1):5–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Cannabis use and other illicit drug use: testing the cannabis gateway hypothesis. Addiction. 2006;101:556–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. The developmental antecedents of illicit drug use: evidence from a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II) In: Hilsenroth MJ, Segal DL, editors. Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment, Vol. 2: Personality Assessment. John Wiley & Son; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Flores PJ. Addiction as an attachment disorder: implications for group therapy. Int. J. Group Psychother. 2001;51:63–81. doi: 10.1521/ijgp.51.1.63.49730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank B. An overview of heroin trends in New York City: past, present and future. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2000;67:340–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossop M, Stewart D, Treacy S, Marsden J. A prospective study of mortality among drug misusers during a 4-year period after seeking treatment. Addiction. 2002;97:39–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbrock MN, Hesselbrock VM. Gender, alcoholism, and psychiatric comorbidity. In: Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, editors. Gender and Alcohol: Individual and Social Perspectives. Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies; New Brunswick, NJ: 1997. pp. 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JP, Cerbone FG. Parental substance use disorder and the risk of adolescent drug abuse: an event history analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:255–264. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JP, Cerbone FG, Su SS. A growth curve analysis of cumulative stress and adolescent drug use. Subst. Use Misuse. 2000;35:687–716. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe D, Brandon M, Hinings D, Schofield G. Attachment Theory, Child Maltreatment and Family Support. Macmillan; London: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Hoffman V, Grella CE, Anglin MD. A 33-year follow-up of narcotics addicts. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2001;58:503–508. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Parenting styles, drug use and children's adjustment in families of young adults. J. Marriage Fam. 1990;52:183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott PA. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Neale MC, Prescott CA. Illicit psychoactive substance use, heavy use, abuse, and dependence in a US population-based sample of male twins. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2000;57:261–69. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1985;142:1259–1264. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best CL, Schnurr PP. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: data from a national sample. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisci L, Vanyukov M, Tarter R. Detection of youth at high risk for substance use disorders: a longitudinal study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2005;19:243–252. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Olino TM. Psychopathology in the adolescent and young adult offspring of a community sample of mothers and fathers with major depression. Psychol. Med. 2005;35:353–365. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Ouimette PC, Kelly HS, Ferro T, Riso LP. Test-retest reliability of team consensus best-estimate diagnoses of Axis I and II disorders in a family study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1994;151:1043–1047. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Erath S, Yu T, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Bates JE. The developmental course of illicit substance use from age 12 to 22: links with depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorders at age 18. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2008;49:877–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01915.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent J, Catanzaro SJ, Callan MB. Stress, alcohol-related expectancies and coping preferences: a replication with adolescents of the Cooper et al. (1992) Model. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1997;58:644–651. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman J, Sholomskas D, Thompson W, Belanger A, Weissman MM. Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnoses: a methodological study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1982;39:879–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessem JM, Hopfer CJ, Haberstick BC, Timberlake DS, Ehringer MA, Smolen A, Hewitt JK. Relationship between adolescent marijuana use and young adult illicit drug use. Behav. Genet. 2006;36:498–506. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA. Adolescent psychopathology: I. prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1993;102:133–144. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Klein DN, Gotlib I. Psychosocial functioning of young adults who have experienced and recovered from major depressive disorder during adolescence. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003;112:353–363. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannuzza S, Fyer AJ. Family Informant Schedule and Criteria (FISC), July 1990 Revision. Anxiety Disorders Clinic, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Elkins I, Iacono WG. Genetic and environmental influences on adolescent substance use and abuse. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000;96:671–677. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20001009)96:5<671::aid-ajmg14>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Drug Intelligence Center . The Economic Impact of Illicit Drug Use on American Society. United States Department of Justice; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Needle R, McMubbin H, Wilsoq M, Reineck R, Lazar A, Mederer H. Interpersonal influences in adolescent drug use - the role of older siblings, parents and peers. Int. J. Addict. 1986;21:739–766. doi: 10.3109/10826088609027390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Substance use and abuse among children and adolescents. Am. Psychol. 1989;2:242–248. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Longitudinal associations between depressive and anxiety disorders: a comparison of two trait models. Psychol. Med. 2008;38:353–363. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J, Chambers WJ, Tabrizi MA, Johnson R. Retrospective assessment of prepubertal major depression with the Kiddie-SADS-E. J. Am. Acad. Child Psychiatry. 1982;21:392–397. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60944-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao U, Daley SE, Hammen C. Relationship between depression and substance use disorders in adolescent women during the transition to adulthood. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2000;39:215–222. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Hauf AMC, Wasserman MS, Paradis AD. General and specific childhood risk factors for depression and drug disorders in early adulthood. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2000;39:223–31. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Comparability of telephone and face-to-face interviews assessing Axis I and II disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1997;154:1593–1598. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Klein DN, Andrews JA, Small JW. Psychosocial functioning of adults who experienced substance use disorders as adolescents. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2007;21:155–164. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Hesselbrock V, Tipp J, Anthenelu R, Bucholz K, Radziminski S. A comparison of DSM-III-R, DSM-IV and ICD-10 substance use disorders diagnoses in 1922 men and women subjects in the COGA study. Addiction. 1994;89:1629–1638. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Biegler GS. SUDAAN User's Manual, release 7.5. Research Triangle Institute; Research Triangle Park, NC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Grekin EF, Williams NA. The development of alcohol use disorders. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005;1:493–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sihvola E, Rose RJ, Dick DM, Pulkkinen L, Marttunen M, Kaprio J. Early-onset depressive disorders predict the use of addictive substances in adolescence: a prospective study of adolescent Finnish twins. Addiction. 2008;103:2045–2053. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer J, Willett J. Modeling the days of our lives: reviewing applications of survival analysis in psychological research. Psychol. Bull. 1991;110:268–290. [Google Scholar]

- Sobin E, Weissman MM, Goldstein RB, Adams P, Wickramaratne P, Warner V, Lish JD. Diagnostic interviewing for family studies: comparing telephone and face-to-face methods for the diagnosis of lifetime psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr. Genet. 1993;3:227–233. [Google Scholar]

- Sung M, Erkanli A, Angold A, Costello E. Effects of age at first substance use and psychiatric comorbidity on the development of substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;75:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen JD, Merikangas KR. The comorbidity of depression and substance use disorders. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2000;20:173–189. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ, Eisen SA, Goldberg J, True W, Meyer JM, Toomey R, Faraone SV, Eaves L. Genetic influences on DSM-III-R drug abuse and dependence: a study of 3,297 twin pairs. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1996;67:473–477. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960920)67:5<473::AID-AJMG6>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden B, McGue M, Iacono WG, Burt AS, Elkins I. Identifying shared environmental contributions to early substance use: the respective roles of peers and parents. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2004;113:440–450. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C, MacMillan HL, Jamieson E. The relationship between parental substance abuse and child maltreatment: findings from the Ontario Health Supplement. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:1409–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Mirin SM. Drug abuse as self-medication for depression: an empirical study. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1992;18:121–129. doi: 10.3109/00952999208992825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. Parental, sibling, and peer influences on adolescent substance use and alcohol problems. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2000;4:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Wiesner M. Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: predictors and outcomes. Dev. Psychopathol. 2004;16:1007–1027. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Vaccaro D, McNamara G. The role of life events, family support, and competence in adolescent substance use: a test of vulnerability and protective factors. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1992;20:349–374. doi: 10.1007/BF00937914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]