Abstract

Aft1p is an iron-responsive transcriptional activator that plays a central role in the regulation of iron metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Aft1p is regulated by accelerated nuclear export in the presence of iron, mediated by Msn5p. However, the transcriptional activity of Aft1p is suppressed under iron-replete conditions in the Δmsn5 strain, although Aft1p remains in the nucleus. Aft1p dissociates from its target promoters under iron-replete conditions due to an interaction between Aft1p and the monothiol glutaredoxin Grx3p or Grx4p (Grx3/4p). The binding of Grx3/4p to Aft1p is induced by iron repletion and requires binding of an iron-sulfur cluster to Grx3/4p. The mitochondrial transporter Atm1p, which has been implicated in the export of iron-sulfur clusters and related molecules, is required not only for iron binding to Grx3p but also for dissociation of Aft1p from its target promoters. These results suggest that iron binding to Grx3p (and presumably Grx4p) is a prerequisite for the suppression of Aft1p. Since Atm1p plays crucial roles in the delivery of iron-sulfur clusters from the mitochondria to the cytoplasm and nucleus, these results support the previous observations that the mitochondrial iron-sulfur cluster assembly machinery is involved in cellular iron sensing.

INTRODUCTION

Iron is essential for various biological processes, including oxygen transport, electron transfer, and many catalytic reactions. However, iron is potentially toxic because it accelerates the generation of reactive oxygen species. Therefore, cells must be equipped with machinery for sensing and regulating intracellular iron (10, 15, 34). The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has served as a model organism to investigate iron metabolism in eukaryotic cells because iron-homeostatic mechanisms are highly conserved between yeast, plants, and animals (7). Iron homeostasis in S. cerevisiae is maintained primarily by the transcriptional activator Aft1p (40). Aft1p is activated only under iron-limiting conditions and then induces the expression of more than 20 genes that comprise the iron regulon (36, 40, 42, 46, 47). The iron regulon includes genes encoding proteins involved in iron uptake and utilization, such as the iron permease Ftr1p and the multicopper ferroxidase Fet3p, which form a high-affinity iron transporting complex (1, 43). Iron-dependent modulation of Aft1p localization is involved in this regulation (48). Aft1p is imported into the nucleus by the nuclear import receptor Pse1p regardless of cellular iron status (45). However, Aft1p is exported from the nucleus by the nuclear export receptor Msn5p under iron-replete conditions (44). As a result, Aft1p accumulates in the nucleus only under iron-limited conditions. However, no evidence has convincingly shown that iron-dependent nuclear export by Msn5p is essential for downregulating the transcriptional activity of Aft1p.

In this study, the mechanism underlying the iron-dependent suppression of Aft1p transcriptional activity was investigated. Aft1p activity was suppressed in a Δmsn5 yeast strain, under iron-replete conditions, even though Aft1p remained in the nucleus. Thus, iron regulates Aft1p by two mechanisms: first, Aft1p is dissociated from target promoters under iron-replete conditions; second, Aft1p is recognized by Msn5p and exported to the cytoplasm (44). This study shows that the dissociation of Aft1p from target DNA is the critical step in the regulation of iron metabolism by Aft1p and that dissociation requires the extramitochondrial monothiol glutaredoxins Grx3p and Grx4p (Grx3/4p) and the mitochondrial ABC exporter Atm1p. Grx3/4p are thought to participate in intracellular transport of iron-sulfur clusters or their related molecules that are assembled in the mitochondria. These results suggest that under iron-replete conditions, iron-sulfur clusters produced by the mitochondria are exported by Atm1p into the cytosol, where the iron-sulfur clusters are bound to Grx3/4p and are subsequently recognized by Aft1p upon interacting with Grx3/4p.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and media.

The yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Y26 (Δaft1 Δmsn5) was derived by sporulation and tetrad dissection of crosses between Y23 (Δaft1 MATa) and Y25 (Δmsn5 MATα). Y30 (Δgrx3 Δgrx4) was derived by sporulation and tetrad dissection of crosses between Y27 (Δgrx3 MATa) and Y29 (Δgrx4 MATα). Disruption of each gene was verified by PCR using specifically designed primers. Strains containing the GRX3-HA or GRX4-HA gene integrated at the chromosomal locus of GRX3 or GRX4, respectively, were constructed using the classical pop-in/pop-out gene replacement method (39). Proper gene replacement was confirmed by PCR using specifically designed primers and DNA sequencing. The GAL-ATM1 strains were maintained in YPGal or SGal medium supplemented with appropriate amino acids. Other cells were grown routinely in YPD or SD medium supplemented with appropriate amino acids. To produce iron-starved conditions, before each assay, cells were cultured for 20 h in iron-free medium, which consisted of yeast nitrogen base without iron, 2% glucose, 50 mM MES (morpholineethanesulfonic acid) buffer (pH 6.1), and 500 μM ferrozine. To deplete Atm1p, the GAL-ATM1 strains were cultivated in SD medium for 48 h prior to analysis.

Table 1.

Yeast strain genotypes

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| PJ69-4A | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-901 his3-200 gal4Δ gal80Δ GAL2-ADE2 LYS2::GAL1-HIS3 met2::GAL7-lacZ | 12 |

| BY4741 | MATa ura3Δ0 leu2Δ his3Δ1 met15Δ0 | 5 |

| BY4742 | MATα ura3Δ0 leu2Δ his3Δ1 lys2Δ0 | 5 |

| Y23 (Δaft1) | BY4741 background, aft1Δ::KanMX | 44 |

| Y24 (Δmsn5) | BY4741 background, msn5Δ::KanMX | This study |

| Y25 | BY4742 background, msn5Δ::KanMX | This study |

| Y26 (Δaft1 Δmsn5) | BY4741 background, aft1Δ::KanMX msn5Δ::KanMX | This study |

| Y27 (Δgrx3) | BY4741 background, grx3Δ::KanMX | This study |

| Y28 (Δgrx4) | BY4741 background, grx4Δ::KanMX | This study |

| Y29 | BY4742 background, grx4Δ::KanMX | This study |

| Y30 (Δgrx3 Δgrx4) | BY4741 background, grx3Δ::KanMX grx4Δ::KanMX | This study |

| Y31 | BY4741 background, GRX3-HA | This study |

| Y32 | BY4741 background, AFT1-TAP::HIS3MX6, GRX3-HA | This study |

| Y33 | BY4741 background, GRX4-HA | This study |

| Y34 | BY4741 background, GRX3-TAP::HIS3MX6, GRX4-HA | This study |

| Y35 (GAL-ATM1) | BY4741 background, pATM1::pGAL1-10-KanMX | This study |

Plasmids.

Expression plasmids for hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Aft1p (Aft1-HA), tandem affinity purification (TAP)-tagged Aft1p (Aft1-TAP), or their mutants, driven by the AFT1 promoter, have been described previously (44). For yeast two-hybrid assays, pAD-AFT1 (44), pBD-GRX3, pBD-GRX4, and pBD-NBP35 were used. The pBD-GRX3, pBD-GRX4, and pBD-NBP35 constructs were created by inserting DNA fragments covering the complete coding regions of GRX3, GRX4, or NBP35 into pGBKT7 (Invitrogen). Expression plasmids for Grx3-HA, Grx4-HA, or their mutants were created by inserting the open reading frames (ORF) of GRX3-HA, GRX4-HA, or their mutants into pRS415 containing the ADH1 promoter.

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy.

The subcellular localization of HA-tagged proteins was examined by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy as described previously (44). Briefly, cells expressing HA-tagged proteins were fixed in 4% formaldehyde. Cell walls were digested with 300 units of Zymolyase (Seikagaku Kogyo), followed by the addition of 2% SDS. Spheroplasts were fixed on polylysine-coated coverslips, permeabilized with 0.05% saponin, and then incubated with an anti-HA antibody (HA.11; Covance). Signals were amplified and visualized using an Alexa Fluor 594 signal amplification kit (Invitrogen). Nuclei were stained by incubation with 500 ng/ml 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min. Fluorescent and differential interference contrast (DIC) images were captured using an FV-1000 confocal microscope (Olympus). Expression of the tagged proteins was measured by immunoblotting and found to be similar in each of the strains under the different iron conditions employed.

Northern blotting.

Cells cultured to mid-log phase were harvested, and total RNA was isolated, as described previously (17). The RNA was separated on a 1% agarose gel containing formaldehyde, transferred to a Biodyne B membrane (Pall Corporation), and hybridized with 32P-labeled probes for FTR1 (nucleotides [nt] 1 to 649 of the FTR1 ORF), FET3 (nt 1 to 582 of the FET3 ORF), FRE1 (nt 1 to 2058 of the FRE1 ORF), SIT1/ARN3 (nt 1 to 1884 of the SIT1/ARN3 ORF), and ACT1 (nt 37 to 1070 of the ACT1 ORF). The hybridized membranes were analyzed using a BAS-2000 imager (GE Healthcare).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Cells carrying the Aft1-TAP plasmid were incubated in 1% formaldehyde for 15 min followed by 125 mM glycine for 5 min at 30°C. Cells were collected and lysed in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5)–500 mM NaCl–1 mM EDTA–1% Triton X-100–0.1% deoxycholate using Multi-Beads Shocker (Yasui Kikai), and the homogenate was then sonicated to shear chromatin. Aft1-TAP was precipitated from an aliquot of the soluble fraction (500 μg total protein) using rabbit IgG-conjugated Dynabeads M-270 Epoxy (Invitrogen). Coprecipitated DNA fragments were incubated in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0)–1 mM EDTA–1% SDS at 65°C for 12 h for reverse cross-linking and then analyzed by semiquantitative PCR to amplify nt −702 to −3 of the FET3 promoter and nt −292 to −33 of the ACT1 promoter. PCR-amplified DNA was separated on 2% agarose gels and analyzed using an LAS-3000 imager (GE Healthcare).

Yeast two-hybrid screening and assays.

Yeast two-hybrid screening for Aft1p-interacting proteins has been described previously (23). The yeast two-hybrid assay was performed by examining the growth of PJ69-4A strains expressing both activation domain (AD)- and binding domain (BD)-fused proteins in medium lacking adenine and histidine. Cells were spotted using 3-fold serial dilutions beginning at 600 cells. All cells showed similar growth on medium containing adenine and histidine.

Coprecipitation.

Cells expressing TAP- and HA-fused proteins were lysed in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) using Multi-Beads Shocker. The soluble fraction was incubated with rabbit IgG-conjugated Dynabeads M-270 Epoxy in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0)–150 mM NaCl–0.5% Triton X-100 at 4°C for 2 h. The beads were washed five times with the same buffer, and precipitates were separated using 9% SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting using anti-HA or anti-TAP antibodies (Thermo Scientific). Expression levels of the fusion proteins were confirmed by immunoblotting an aliquot of each cell lysate using the anti-HA and anti-TAP antibodies.

Iron binding to Grx3p in vivo.

Cells expressing Grx3-TAP were cultured in iron-depleted medium to mid-log-phase growth. Cells (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 10) were radiolabeled with 370 kBq of 55Fe for 30 min. Cells were washed with 50 mM citrate (pH 7.4)–1 mM EDTA and lysed in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 2 mM PMSF using Multi-Beads Shocker. Grx3-TAP was precipitated from lysates (5 mg total protein) with rabbit IgG-conjugated Dynabeads M-270 Epoxy, and coprecipitated 55Fe was quantified by scintillation counting. The precipitated protein was assessed by immunoblotting using an anti-TAP antibody.

RESULTS

Iron mediates growth suppression in constitutively active Aft1p cells but not in Δmsn5 cells.

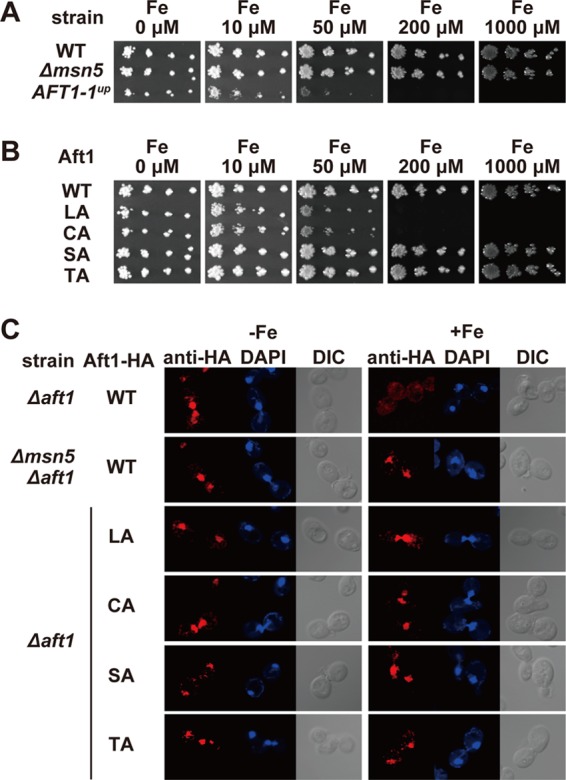

Aft1-1up, which is a C291F mutant, is constitutively nuclear and activates the expression of target genes regardless of the iron status of the cells (46–48). The growth of the AFT1-1up mutant strain is inhibited under iron-replete conditions, possibly because of iron toxicity (46). We confirmed that the growth of the AFT1-1up mutant strain was inhibited in the presence of as little as 50 μM iron in the medium (Fig. 1A). The nuclear export receptor Msn5p is required for the iron-mediated nuclear export of Aft1p, and, consequently, Aft1p resides in the nucleus regardless of the iron concentration in the medium in the Δmsn5 strain (44) (Fig. 1C). However, in contrast to that of the AFT1-1up strain, the growth of the Δmsn5 strain was not retarded under iron-replete conditions and appeared similar to that of the wild-type (WT) strain (Fig. 1A).

Fig 1.

The Δmsn5 strain is not sensitive to excess iron. (A) The indicated strains were spotted on SD medium supplemented with the indicated concentrations of FeSO4 using 3-fold serial dilutions beginning at 200 cells per spot. Cell growth was observed after incubation at 30°C for 3 days. (B) The growth of cells expressing the indicated Aft1p mutants was tested as for panel A. (C) Aft1p accumulates in the nucleus of the Δmsn5 strain independent of cellular iron status. Δaft1 or Δmsn5 Δaft1 cells carrying an expression plasmid for wild-type Aft1-HA or the indicated mutants were cultured in iron-depleted (−Fe) or iron-replete (+Fe) medium to mid-log-phase growth. After fixation, the subcellular localization of Aft1-HA was examined by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy using an anti-HA antibody. DAPI staining of nuclei and differential interference contrast (DIC) images are provided for comparison.

Several amino acid residues of Aft1p, including Leu99, Leu102, Ser210, Ser224, Cys291, Cys293, Thr421, Thr423, Thr431, and Thr435, play important roles in the iron-responsive nuclear export of Aft1p (44, 48). Aft1p mutants in which some of those amino acid residues were replaced by alanine were generated {Aft1pLeu99/102Ala [Aft1p(LA)], Aft1pSer210/224Ala [Aft1p(SA)], Aft1pCys291/293Ala [Aft1p(CA)], and Aft1pThr421/423/431/435Ala [Aft1p(TA)]}). The mutants were introduced into Δaft1 cells to generate cells expressing only the Aft1p mutant. The Aft1p mutants were localized in the nucleus even under iron-replete conditions (Fig. 1C), and the effect of iron on the growth of cells expressing these Aft1p mutants was examined. Although cells expressing Aft1p(LA) or Aft1p(CA) grew poorly in high-iron medium, as observed in the AFT1-1up strain, the growth of cells expressing Aft1p(SA) or Aft1p(TA) was not retarded in iron-rich medium (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that nuclear retention of Aft1p is not sufficient to induce iron-mediated growth suppression.

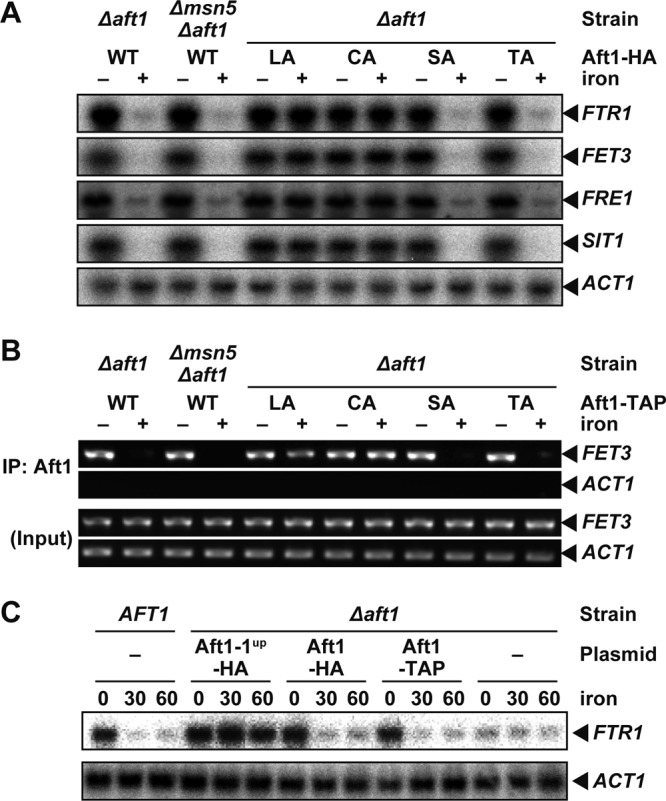

Aft1p dissociates from its target promoters in response to iron repletion.

The growth of the AFT1-1up strain and of cells expressing Aft1p(LA) or Aft1p(CA) was retarded in high-iron medium, whereas iron exerted virtually no effect on the growth of the Δmsn5 strain or cells expressing Aft1p(SA) or Aft1p(TA), despite the fact that Aft1p localizes in the nucleus under iron-replete conditions (Fig. 1). Although Ser210, Ser224, Thr421, Thr423, Thr431, and Thr435, which are mutated in Aft1p(SA) or Aft1p(TA), are involved in interactions with Msn5p, Leu99, Leu102, Cys291, and Cys293 do not appear to be involved in binding Msn5p (44). To dissect the differential roles of these two groups of amino acid residues, we tested the iron-regulated expression of Aft1p target genes (FET3, FTR1, FRE1, and SIT1/ARN3) by Northern blotting (Fig. 2A). The mRNA levels for these genes were high under iron-depleted conditions in all strains, suggesting that mutation of these amino acid residues did not affect the transcriptional activation activity of Aft1p. Expression of the iron regulon decreased under iron-replete conditions in the Δmsn5 strain, as well as in Aft1p(SA)- and Aft1p(TA)-expressing cells, similar to the case for cells expressing wild-type Aft1p. However, in Aft1p(LA)- or Aft1p(CA)-expressing cells, the iron regulon was not substantially downregulated under iron-replete conditions. Previously, target DNA binding by Aft1p was suggested by in vivo footprinting to occur only under iron-limited conditions (47). Indeed, chromatin immunoprecipitation revealed that Aft1p bound to the Aft1p-regulated FET3 promoter only under iron-limited conditions in the Δmsn5 strain, as well as in cells expressing Aft1p(SA) or Aft1p(TA) and in wild-type cells (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the Aft1p(LA) and Aft1p(CA) mutants bound to the FET3 promoter even under iron-replete conditions (Fig. 2B). The Δaft1 strain transformed with a centromere-based plasmid expressing Aft1-TAP under control of the AFT1 promoter expressed and regulated Aft1p target genes in a manner identical to that of cells expressing the wild-type Aft1p (Fig. 2C), indicating that Aft1-TAP is functional. These results are consistent with the previous observations that replacement of Leu99 with Ala and of Cys291 with Phe generated a constitutively active Aft1p transcriptional activator (31, 46, 48). Thus, iron-replete conditions appear to induce not only Aft1p nuclear export but also the dissociation of Aft1p from target promoters, and Cys291, Cys293, Leu99 and Leu102 appear to be involved in the dissociation of Aft1p from the iron regulon promoters.

Fig 2.

Aft1p dissociates from a target promoter in response to iron repletion. (A) Expression of the iron regulon is suppressed in iron-replete Δmsn5 cells. Δaft1 or Δmsn5 Δaft1cells carrying an expression plasmid for wild-type Aft1-HA or the indicated mutants were cultured in iron-free medium to mid-log-phase growth. Cells were cultured for an additional 30 min in the absence (− iron) or presence (+ iron) of 200 μM FeSO4, and total RNA was extracted. The mRNA levels of the indicated genes were then analyzed by Northern blotting. (B) Aft1p binds to the FET3 promoter only under iron-deprived conditions in Δmsn5 cells. Δaft1 or Δmsn5 Δaft1 cells carrying an expression plasmid for wild-type Aft1-TAP or the indicated mutants were cultured as for panel A, and Aft1p binding to the FET3 and ACT1 promoters was detected by chromatin immunoprecipitation (IP). (C) Aft1-TAP is functional. BY4741 (AFT1) cells, Δaft1 cells, and Δaft1 cells carrying an expression plasmid for Aft1-TAP, Aft1-HA, or Aft1-1up-HA were cultured in iron-free medium to mid-log-phase growth. Total RNA was isolated after the addition of iron at the indicated times, and mRNA levels of the indicated genes were analyzed by Northern blotting.

Involvement of Leu99, Leu102, Cys291, and Cys293 in Aft1p interactions with Grx3p and Grx4p.

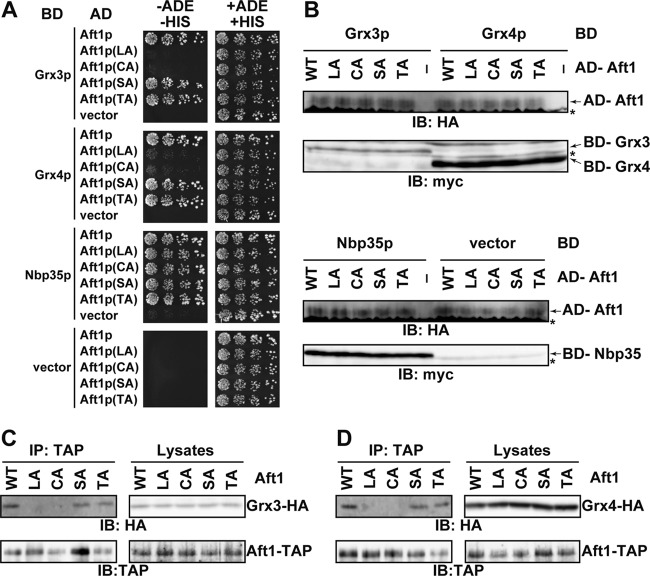

To elucidate the mechanism underlying dissociation of Aft1p from the iron regulon promoters in iron-replete cells, yeast two-hybrid screening was used to identify proteins that are involved in regulation of Aft1p (23). Using Aft1p lacking the transactivation domain [Aft1(1-413)] as prey, we identified six candidate genes, three of which encode iron-sulfur proteins: Nbp35p and two monothiol glutaredoxin homologs, Grx3p and Grx4p (Grx3/4p). We tested if the interaction between Aft1p and these candidates for Aft1p-interacting proteins requires Leu99, Leu102, Cys291, and Cys293 of Aft1p, and we found that Grx3/4p did not bind to Aft1p(LA) or Aft1p(CA) in a yeast two-hybrid assay, although Aft1p(SA) and Aft1p(TA) did interact with Grx3/4p (Fig. 3A). Immunoblot analyses of cellular extracts using both anti-HA (for AD-fused proteins) and anti-myc (for BD-fused proteins) showed that the fusion proteins were expressed in cotransformed cells, although expression of BD-Grx4p was higher than that of BD-Grx3p (Fig. 3B). The interaction between Aft1p and Grx3/4p was also examined by coimmunoprecipitation analyses. Consistent with the results obtained with the yeast two-hybrid assays, neither Aft1p(LA) nor Aft1p(CA) coprecipitated with Grx3/4p, whereas Aft1p, Aft1p(SA), and Aft1p(TA) did coprecipitate (Fig. 3C and D). These results indicate that Aft1p interacts with Grx3/4p and that the Aft1p residues Leu99, Leu102, Cys291, and Cys293 are involved in this interaction, raising the possibility that Grx3/4p are involved in the dissociation of Aft1p from target promoters in response to iron repletion.

Fig 3.

Leu99, Leu102, Cys291, and Cys293 are required for the Aft1p-Grx3/4p interaction. (A) The PJ69-4A strain was transformed with an expression plasmid for AD-fused Aft1p, mutant Aft1p, or the corresponding empty vector, as well as an expression plasmid for the indicated BD-fused proteins or the corresponding empty vector. Cells were grown at 30°C for 4 days on SD medium lacking (−ADE −HIS) or containing (+ADE +HIS) adenine and histidine. Cells were spotted using 3-fold serial dilutions beginning at 600 cells per spot. (B) Lysates from the cells used for panel A were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA (for the detection of AD-fused proteins) or with anti-myc (for the detection of BD-fused proteins). *, nonspecific bands. (C and D) Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells carrying expression plasmids for Aft1-TAP or the indicated mutants and Grx3-HA (C) or Grx4-HA (D) were cultured in iron-depleted medium to mid-log-phase growth. Cells were cultured for an additional 15 min in the presence of 200 μM FeSO4. TAP-precipitates and lysates were probed with the indicated antibodies.

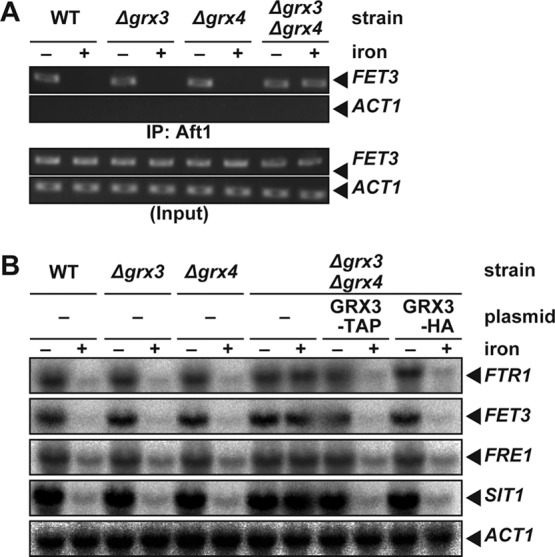

Grx3/4p are required for the iron-dependent dissociation of Aft1p from target promoters.

GRX3 and/or GRX4 deletion strains were constructed to test whether the binding of Aft1p to the FET3 promoter is regulated by iron. In the strains that lacked either Grx3p or Grx4p, Aft1p dissociated from the FET3 promoter in response to iron repletion as observed in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4A). When both GRX3 and GRX4 were deleted, Aft1p occupied the FET3 promoter even under iron-replete conditions (Fig. 4A). The Aft1p-regulated iron regulon was highly expressed even under iron-replete conditions in Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells but not Δgrx3 or Δgrx4 cells (Fig. 4B), similar to previous results (31). These results indicate that Grx3/4p are required for iron suppression of transcription of the iron regulon by inducing iron-dependent dissociation of Aft1p from target promoters.

Fig 4.

Grx3/4p are required for the dissociation of Aft1p from DNA in response to iron. (A) Grx3/4p are required for the iron-dependent dissociation of Aft1p from the FET3 promoter. BY4741 (WT), Δgrx3, Δgrx4, or Δgrx3 Δgrx4 strains carrying expression plasmids for Aft1-TAP were cultured in iron-free medium to mid-log-phase growth. Cells were cultured for an additional 30 min in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 200 μM FeSO4, and Aft1p binding to the FET3 and ACT1 promoters was detected by chromatin immunoprecipitation. (B) Iron regulon expression is not suppressed even under iron-replete conditions in the Δgrx3 Δgrx4 strain. The BY4741 (WT), Δgrx3, Δgrx4, and Δgrx3 Δgrx4 strains, or Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells carrying expression plasmids for Grx3-TAP or Grx3-HA, were cultured as for panel A, and expression of the indicated genes was analyzed by Northern blotting.

The interaction between Aft1p and Grx3/4p is augmented under iron-replete conditions.

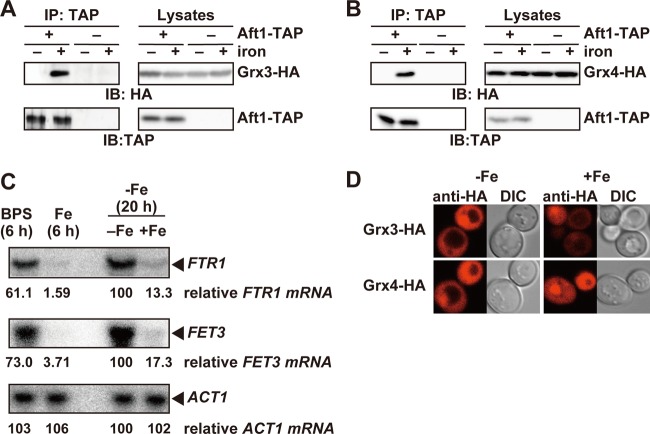

The above results suggested that the interaction between Aft1p and Grx3/4p plays a crucial role in dissociation of Aft1p from target promoters under iron-rich conditions. Hence, we examined whether the interaction between Aft1p and Grx3/4p is induced upon iron repletion in order to suppress the transcriptional activation activity of Aft1p. Cells containing both AFT1-TAP and GRX3-HA integrated at the chromosomal loci of AFT1 and GRX3, respectively, were constructed. Grx3-HA is functional, because the expression of the iron regulon was normally regulated by iron in Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells expressing Grx3-HA (Fig. 4B). Cells expressing Aft1-TAP and Grx3-HA were first cultured in iron-free medium (SD lacking ferric chloride and supplemented with 500 μM ferrozine) for 20 h to ensure iron starvation. Cells were then cultured for 15 min in the presence of 200 μM ferrous sulfate. Cell lysates were prepared before or 15 min after the addition of 200 μM ferrous sulfate, and coprecipitation experiments were performed. Grx3p-HA was effectively coprecipitated with Aft1p-TAP in lysates from cells after iron repletion, whereas minimal amounts of Grx3p-HA coprecipitated with Aft1p-TAP in lysates from iron-starved cells (Fig. 5A). Similarly, Grx4-HA was effectively coprecipitated with Aft1-TAP only after iron repletion (Fig. 5B). In contrast, previous reports suggest that Grx3/4p interact with Aft1p regardless of the iron status of cells (19, 31). Kumánovics et al. indicated that Aft1-TAP is effectively coprecipitated with Grx3p under both high- and low-iron conditions (19). In their analysis, cells were cultivated in SD medium containing either 250 μM iron sulfate or 40 μM bathophenanthrolinedisulfonate (BPS), an impermeable iron(II) chelator, for 6 h to produce high- or low-iron conditions, respectively (19). The expression of iron regulon genes, including FET3 and FTR1, was induced under the iron-depleted condition. The levels of FTR1 and FET3 mRNAs were higher in cells cultivated for 20 h in SD medium lacking iron than in cells cultivated for 6 h in SD medium containing BPS (Fig. 5C). This result suggests that treatment with BPS for 6 h does not completely deprive the cells of iron and that a substantial amount of iron bound to Grx3/4p, accounting for the interaction between Aft1p and Grx3/4p in cells treated with BPS for 6 h, as observed in the previous study (18). However, in the BPS-treated cells, the Grx3/4p may not be fully saturated with iron and some free Aft1p may be available to induce the expression of the iron regulon. Moreover, indirect immunofluorescence analyses revealed that Grx3/4p reside in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm, and changes in cellular iron status did not overtly affect their subcellular localization (Fig. 5D), as reported previously (19, 24). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that iron induces the interaction between Aft1p and Grx3/4p.

Fig 5.

The Grx3/4p interaction with Aft1p is augmented in the presence of iron. (A and B) Binding of Grx3/4p to Aft1p is enhanced under iron-replete conditions. (A) Cells expressing both Aft1-TAP and Grx3-HA (+ Aft1-TAP) or Grx3-HA alone (− Aft1-TAP) from their natural chromosomal loci were cultured in iron-free medium to mid-log-phase growth (20 h). Cells were cultured for an additional 15 min in the absence (− iron) or presence (+ iron) of 200 μM FeSO4, and TAP immunoprecipitates and cell lysates were probed with the indicated antibodies. (B) Cells expressing both Aft1-TAP and Grx4-HA (+ Aft1-TAP) or Grx4-HA alone (− Aft1-TAP) from their natural chromosomal loci were cultured as for panel A, and the interaction between Aft1-TAP and Grx4-HA was analyzed by immunoprecipitation. (C) Induction of the expression of the iron regulon is incomplete after a 6-h treatment with 40 μM BPS. BY4741 cells were cultured under the following conditions: SD medium containing 40 μM BPS for 6 h (BPS), SD medium containing 250 μM FeSO4 for 6 h (Fe), SD medium lacking iron for 20 h (Fe; −), or SD medium lacking iron for 20 h with an additional 15-min cultivation in the presence of 200 μM FeSO4 (Fe; +). Total RNA was extracted, and expression of the indicated genes was analyzed by Northern blotting. The values indicated below each panel are relative mRNA levels as a percentage of the amount in the cells cultured in SD medium lacking iron for 20 h. (D) Grx3/4p reside both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm. Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells carrying expression plasmids for Grx3/4-HA were cultured in iron-free medium to mid-log-phase growth. Cells were cultured for an additional 30 min in the absence (−Fe) or presence (+Fe) of 200 μM FeSO4. After fixation, the subcellular localization of Grx3/4-HA was examined by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy using an anti-HA antibody. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images are provided for comparison.

Grx3/4p require an iron-sulfur cluster to interact with Aft1p.

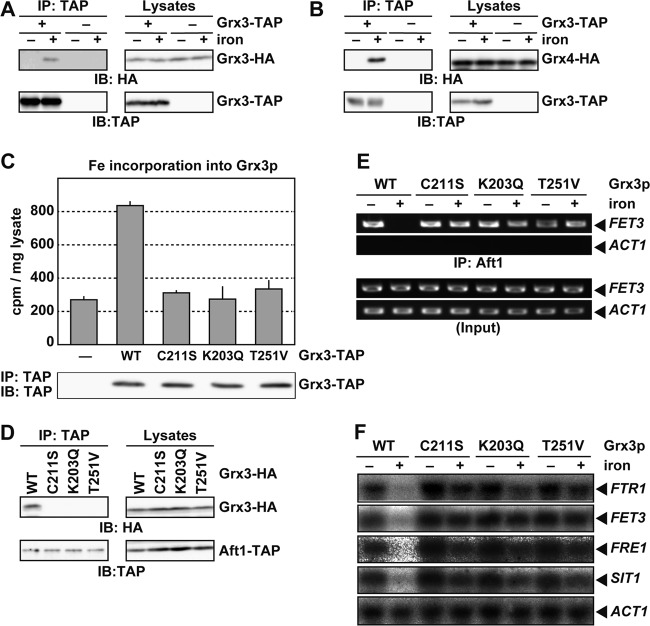

Several lines of evidence suggest that ligation of a [2Fe-2S] cluster plays a crucial role in dimer formation by monothiol glutaredoxins in vitro and in vivo (26, 35). Because Grx3/4p-Aft1p binding appeared to be regulated by the iron status of cells, a [2Fe-2S] cluster- and/or [2Fe-2S] cluster-dependent dimerization of Grx3/4p may be involved in the Grx3/4p-Aft1p interactions. To address the possibility, we first tested the iron-dependent dimerization of Grx3/4p. We expressed Grx3-TAP, which was shown to be functional (Fig. 4B), and Grx3-HA in Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells. Cells were cultured in iron-free medium for 20 h, and coprecipitation experiments were performed using cell lysates that were prepared before or 15 min after the addition of 200 μM ferrous sulfate. As shown in Fig. 6A, Grx3-HA is coprecipitated effectively with Grx3-TAP in the lysate of iron-replete cells but not in the lysate of iron-starved cells. To verify iron-dependent dimerization of monothiol glutaredoxins in physiological settings, we constructed cells with both GRX3-TAP and GRX4-HA integrated at the chromosomal loci of GRX3 and GRX4, respectively. Coprecipitation analyses revealed that Grx3-TAP and Grx4-HA form stable complexes only under iron-rich conditions (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that Grx3/4p dimerize in an iron-dependent manner, raising the possibility that Grx3/4p bind to Aft1p in the dimer form.

Fig 6.

Grx3/4p require an iron-sulfur cluster to interact with Aft1p. (A and B) Grx3-TAP and Grx3-HA interact under iron-replete conditions. (A) Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells carrying expression plasmids for Grx3-TAP and Grx3-HA were cultured in iron-free medium to mid-log-phase growth (20 h). Cells were cultured for an additional 15 min in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 200 μM FeSO4, and TAP immunoprecipitates and cell lysates were probed with the indicated antibodies. (B) Cells expressing both Grx3-TAP and Grx4-HA (+ Aft1-TAP) or Grx4-HA alone (− Aft1-TAP) from their original chromosomal loci were cultured as for panel A, and interactions between Grx3-TAP and Grx4-HA were analyzed by immunoprecipitation. (C) Lys203, Thr251, and Cys211 of Grx3p are important for iron binding by Grx3p in vivo. Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells carrying an expression plasmid for Grx3 (−), Grx3-TAP (WT), or the indicated mutants were cultured in iron-free medium to mid-log-phase growth. Cells were radiolabeled with 370 kBq of 55Fe for 2 h. TAP-tagged proteins were precipitated, and bound 55Fe was quantified by scintillation counting. Data represent mean values from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations (SD). The amount of precipitated proteins was assessed by immunoblotting using an anti-TAP antibody. (D) Lys203, Thr251, and Cys211 of Grx3p are important for the Aft1p-Grx3p interaction. Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells carrying expression plasmids for Aft1-TAP and Grx3-HA or the indicated mutants were cultured in iron-depleted medium to mid-log-phase growth. Cells were cultured for an additional 15 min in the presence of 200 μM FeSO4, and TAP immunoprecipitates and cell lysates were probed with the indicated antibodies. (E) Lys203, Thr251, and Cys211 of Grx3p are important for the iron-dependent dissociation of Aft1p from the FET3 promoter. Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells carrying expression plasmids for Aft1-TAP and Grx3p-HA or the indicated mutants were cultured in iron-free medium to mid-log-phase growth. Cells were cultured for an additional 30 min in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 200 μM FeSO4, and Aft1p binding to the FET3 and ACT1 promoters was probed by chromatin immunoprecipitation. (F) Lys203, Thr251, and Cys211 of Grx3p are important for the regulation of FTR1 expression by iron. Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells carrying an expression plasmid for Grx3p-HA or the indicated mutants were cultured in iron-depleted medium to mid-log-phase growth. Cells were cultured for an additional 30 min in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 200 μM FeSO4, and the expression of FTR1, FET3, FRE1, SIT1, and ACT1 was analyzed by Northern blotting.

Next, Grx3p mutants that cannot bind iron were constructed. Since Cys31 and glutathione binding residues such as Lys23 and Thr71 of a cyanobacterial Grx3p, which is homologous to Grx3/4p, is involved in [2Fe-2S] cluster ligation (35), the corresponding residues of S. cerevisiae Grx3p were mutated: Cys211 to Ser, Lys203 to Gln, and Thr251 to Val (Grx3pC211S, Grx3pK203Q, and Grx3pT251V, respectively). To analyze iron binding by these Grx3p mutants in vivo, Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells expressing TAP-tagged wild-type or mutant Grx3p were cultured in the presence of 55Fe. Subsequently, TAP-tagged Grx3p proteins were immunoprecipitated and the amount of coprecipitated 55Fe was quantified by scintillation counting. Wild-type Grx3p bound 55Fe, but the Grx3pC211S, Grx3pK203Q, and Grx3pT251V mutants failed to bind 55Fe (Fig. 6C), indicating that these residues are important for iron-sulfur ligation by S. cerevisiae Grx3p. Whether these Grx3p mutants can bind to Aft1p was examined by coimmunoprecipitation analyses. The wild-type Grx3p, but not the C211S, K203Q, or T251V mutants, coprecipitated with Aft1p (Fig. 6D), suggesting that [2Fe-2S] cluster ligation by Grx3p is a prerequisite for Aft1p-Grx3p interactions. The Grx3p mutants were expressed in Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells, and promoter occupation by Aft1p and expression of Aft1p target genes were evaluated. As shown in Fig. 6E, Aft1p occupied the FET3 promoter even under iron-replete conditions in cells expressing the Grx3p mutants that failed to ligate the iron-sulfur cluster, but Aft1p dissociated from the FET3 promoter in iron-replete cells expressing wild-type Grx3p. Northern blotting revealed that expression of the iron regulon was not reduced in response to iron in Δgrx3 Δgrx4 cells expressing the C211S, K203Q, or T251V mutants of Grx3p but was reduced in cells expressing wild-type Grx3p (Fig. 6F). Collectively, these results indicate that ligation of a [2Fe-2S] cluster by Grx3p is necessary for dissociation of Aft1p from its target promoters.

Atm1p is required for iron-sulfur loading onto Grx3/4p and Aft1p regulation by iron.

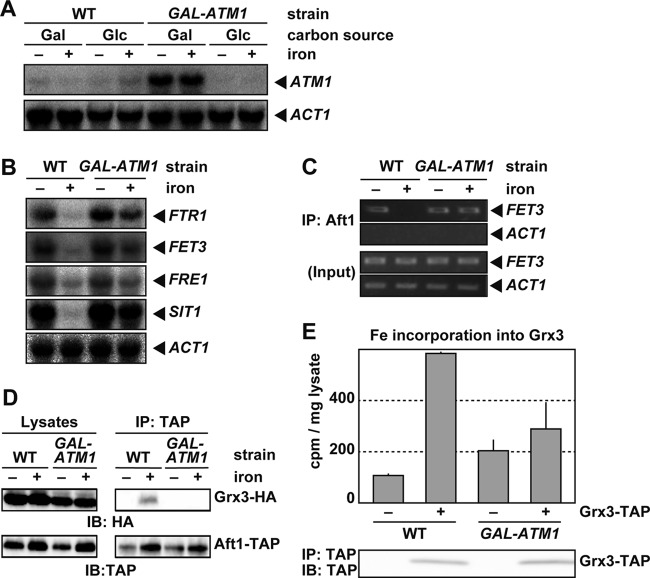

Defects in the iron-sulfur cluster assembly (ISC) machinery in mitochondria lead to reductions in iron binding by Grx3/4p in vivo (26). Thus, whether iron-sulfur clusters transported from the mitochondria are involved in iron-sulfur cluster loading by Grx3/4p in the cytosol or nucleus was examined. The mitochondrial ABC transporter Atm1p has been suggested to be an exporter of iron-sulfur clusters or related molecules (16, 22). Whether Atm1p is required for iron-sulfur cluster loading onto Grx3/4p and, therefore, the iron-dependent dissociation of Aft1p from target promoters was examined. A strain in which ATM1 gene expression was driven by the glucose-repressible GAL1-10 promoter (GAL-ATM1) was constructed, as described previously (2). To repress the GAL1-10 promoter and deplete Atm1p, the GAL-ATM1 strain was grown for 48 h on synthetic medium containing d-glucose as a sole carbon source (2). As shown in Fig. 7A, the expression of ATM1 in the GAL-ATM1 strain was undetectable by Northern blotting after culture in the glucose medium. Wild-type control cells were also cultured on the glucose-containing medium for these experiments. In the GAL-ATM1 strain, expression of the iron regulon did not decrease under iron-rich conditions, as reported previously (41), indicating that expression of Atm1p was adequately suppressed in the GAL-ATM1 strain (Fig. 7B). Expression of iron regulon transcripts decreased in the wild type, but not in the GAL-ATM1 strain, in the presence of iron. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses revealed that Aft1p bound to the FET3 promoter regardless of iron status in the Atm1p-depleted (GAL-ATM1) cells (Fig. 7C). The interaction between Aft1p and Grx3p in Atm1p-depleted cells was assessed by coimmunoprecipitation. In the wild-type strain, Grx3p coprecipitated with Aft1p under iron-replete conditions, but Grx3p failed to interact with Aft1p in iron-replete Atm1p-depleted cells (Fig. 7D). Since ligation of the iron-sulfur cluster by Grx3p appears to be a prerequisite for interactions between Grx3p and Aft1p, 55Fe binding to Grx3p in iron-replete cells was assessed, as described in the legend to Fig. 6C. The amount of 55Fe in Grx3p immunoprecipitates was significantly lower in Atm1p-depleted cells than in wild-type cells (Fig. 7E). Collectively, these results indicate that Atm1p is involved in iron-sulfur cluster loading by Grx3p, the net result of which is dissociation of Aft1p from target promoters in iron-replete cells.

Fig 7.

Atm1p is required for Aft1p inactivation in response to iron. (A) The ATM1 mRNA is depleted in GAL-ATM1 strains cultured in glucose-containing medium. The wild-type or Atm1p-depleted GAL-ATM1 strains were cultured in iron-free medium containing galactose (Gal) or glucose (Glc) as a sole carbon source to mid-log-phase growth. Cells were cultured for an additional 30 min in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 200 μM FeSO4, and the ATM1 and ACT1 mRNA levels were analyzed by Northern blotting. (B) Iron regulon expression remains high under iron-replete conditions in Atm1p-depleted cells. The wild-type or Atm1p-depleted GAL-ATM1 strains were cultured in iron-free medium to mid-log-phase growth. Cells were cultured for an additional 30 min in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 200 μM FeSO4, and the expression of FTR1, FET3, FRE1, SIT1, and ACT1 was analyzed by Northern blotting. (C) Atm1p is required for the iron-dependent dissociation of Aft1p from the FET3 promoter. The wild-type or Atm1p-depleted GAL-ATM1 strains expressing Aft1-TAP were cultured in iron-free medium to mid-log-phase growth. Cells were cultured for an additional 30 min in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 200 μM FeSO4, and Aft1p binding to the FET3 and ACT1 promoters was analyzed by chromatin immunoprecipitation. (D) Atm1p is required for the Aft1p-Grx3p interaction. The wild-type or Atm1p-depleted GAL-ATM1 strains expressing Aft1-TAP and Grx3-HA were cultured in iron-free medium to mid-log-phase growth. Cells were cultured for an additional 15 min in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 200 μM FeSO4, and the interaction between Aft1-TAP and Grx3-HA was analyzed by coimmunoprecipitation. (E) Atm1p is important for iron binding by Grx3p in vivo. The wild-type or Atm1p-depleted GAL-ATM1 strains expressing nontagged Grx3p (−) or Grx3-TAP (+) were cultured in iron-free medium to mid-log-phase growth. Cells were radiolabeled with 370 kBq of 55Fe for 30 min. TAP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated, and bound 55Fe was quantified by scintillation counting. Data represent mean values from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate SD. The amount of precipitated protein was assessed by immunoblotting using an anti-TAP antibody.

DISCUSSION

The activity of Aft1p, a central transcriptional regulator of iron metabolism in S. cerevisiae, is regulated by iron-dependent nuclear export of Aft1p mediated by the nuclear export receptor Msn5p (44). This study demonstrates another layer of iron regulation of Aft1p: Aft1p dissociates from target promoters in response to iron repletion.

Several transcriptional regulators are exported by Msn5p. Crz1p, a calcineurin-responsive transcriptional activator, is regulated, in part, by Msn5p-mediated nuclear export. Calcineurin-mediated dephosphorylation of Crz1p suppresses Msn5p-mediated nuclear export. In Δmsn5 cells, some Crz1p is localized in the nucleus and activates the Crz1p-responsive CDRE promoter (4). Thus, Msn5p-mediated nuclear export is required to suppress Crz1p activity. However, Msn5p-mediated nuclear export of some transcriptional regulators is not required for their suppression. For example, Pho4p is a transcription factor that regulates a variety of genes in response to phosphate availability, and Msn5p-mediated nuclear export of Pho4p is regulated by Pho4p phosphorylation under phosphate-rich conditions (32). Pho4p has multiple phosphorylation sites, and phosphorylation of some of these induces the Pho4p interaction with Msn5p (14). However, phosphorylation of Pho4p at a different site disrupts the interaction with its dimerization partner, Pho2p, and thereby suppresses Pho4p transcriptional activator activity (18). Nuclear export of Mig1p, a transcriptional repressor that represses a number of genes in the presence of glucose (28, 29), is also mediated by Msn5p (8). However, phosphorylation of Mig1p, induced by glucose deprivation, not only facilitates Msn5p-mediated nuclear export of Mig1p but also induces dissociation from the corepressor complex (8, 33). Therefore, Msn5p-mediated nuclear export is not required for suppression of Pho4p or Mig1p activity. Here, Msn5p-mediated nuclear export was shown to be dispensable for iron-mediated suppression of Aft1p transcriptional activity (Fig. 2). Msn5p-mediated nuclear export of Crz1p, Pho4p, and Mig1p is regulated by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation (4, 8, 14). Although phosphorylation of Aft1p is necessary for recognition by Msn5p, Aft1p phosphorylation is not regulated by cellular iron status (44).

The present study has demonstrated that iron-mediated dissociation of Aft1p from target DNA sequences occurs prior to Msn5p-mediated nuclear export. Since earlier work showed that dimerization or multimerization of Aft1p was required for Aft1p-Msn5p binding (44), Aft1p must form multimers after dissociation from the target sequences and is then recognized by Msn5p. Therefore, it would be of interest to determine whether phosphorylation of Crz1p, Pho4p, or Mig1p induces dimerization of the transcriptional regulators as an essential step in Msn5p recognition.

Grx3/4p play crucial roles in iron-mediated suppression of the transcriptional activity of Aft1p (31, 37). However, the precise roles played by Grx3/4p in Aft1 regulation had not been determined previously. Here, we showed that Grx3/4p induced Aft1p dissociation from the target promoters through an enhanced interaction with Aft1p under iron-replete conditions. Aft1p mutants that were unable to interact with Grx3/4p did not dissociate from the Aft1p-regulated gene promoters even under iron-rich conditions (Fig. 1 to 3). Grx3/4p failed to dimerize under severe iron-deprived conditions (Fig. 6). Several lines of evidence suggest that iron bound to Grx3/4p in cells is in the form of a [2Fe-2S] cluster. When overproduced in Escherichia coli, the GRX domain of Grx3/4p binds a [2Fe-2S] cluster utilizing the cysteine located within the conserved CGFS motif (Cys211 for Grx3p and Cys171 for Grx4p) and a glutathione cofactor (35). The conserved Cys within the CGFS motifs and the amino acids that are involved in glutathione binding are thus implicated in [2Fe-2S] binding. Mutations of these amino acids in Grx3/4p reduced iron incorporation into Grx3/4p to near-background levels in vivo and suppressed the binding of Grx3p to Aft1p (Fig. 6) (26). Moreover, glutathione depletion in cells impairs iron incorporation into Grx3/4p (26). Therefore, iron binding to Grx3/4p appears to be a prerequisite for dimerization and Aft1p interactions with the monothiol glutaredoxins. Whether dimerization of Grx3/4p is sufficient for binding to Aft1p or whether iron itself, bound to Grx3/4p, is required for the interaction with Aft1p will be of interest to determine in future studies.

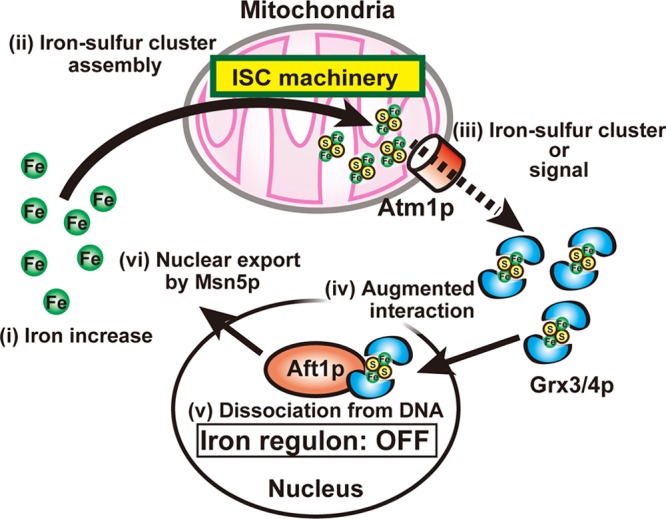

Iron-sulfur clusters are generated in mitochondria (27), and defects in proteins in the mitochondrial ISC machinery result in constitutive expression of Aft1p-regulated genes (41). A previous report indicated that the ISC machinery is required for iron incorporation into Grx3/4p in vivo (26). The mitochondrial ABC exporter Atm1p has been implicated in the export of iron-sulfur clusters or related molecules from mitochondria into the cytosol, because iron loading of several extramitochondrial iron-sulfur proteins, such as Leu1p and Nbp35p, is decreased in Atm1p-depleted strains (16, 22). In this study, Atm1p depletion significantly decreased both binding of Grx3p to iron and binding of Grx3p to Aft1p under iron-replete conditions and resulted in misregulation of Aft1p (Fig. 8). Although heme and intermediates in the heme biosynthetic pathway may also be Atm1p substrates (2, 20), heme is not required for Aft1p inhibition by iron (6). The possibility that the iron bound to Grx3/4p that is required for the interaction between Grx3/4p and Aft1p is not in the form of an iron-sulfur cluster cannot be excluded. However, our results strongly indicate that iron-sulfur clusters or molecules that invoke iron-sulfur cluster formation, which are generated in mitochondria and exported from mitochondria by Atm1p, are involved in iron-sulfur cluster loading of Grx3p and probably Grx4p, although the mechanism for cluster loading of Grx3/4p in the nucleus reminds to be elucidated. Since Grx3/4p binding to Aft1p is strongly augmented in iron-replete cells and iron binding of Grx3p is a prerequisite for the interaction with Aft1p (Fig. 6), iron-sulfur clusters or related molecules generated in the mitochondria and transported by Atm1p appear to play crucial roles in Grx3/4p binding to Aft1p in iron-replete cells. The net result of these interactions is dissociation of Aft1p from target promoters (Fig. 8). This result is consistent with the previous observation that the mitochondrial ISC machinery is involved in cellular iron sensing (41).

Fig 8.

Proposed model for iron sensing by Aft1p. During iron starvation, iron-sulfur assembly in the mitochondria and dimeric Grx3/4p with bound iron-sulfur clusters are minimal. Under these conditions, Grx3/4p binding to Aft1p is attenuated, and Aft1p binds to target promoters to increase the expression of the iron regulon. In response to iron availability (i), iron-sulfur cluster assembly in the mitochondria increases (ii), and the iron-sulfur clusters, or signals that invoke iron-sulfur cluster formation, are delivered to the monothiol glutaredoxins Grx3/4p, which reside in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, via the mitochondrial ABC exporter Atm1p (iii). Grx3/4p with bound iron-sulfur clusters bind to Aft1p (iv), which induces dissociation of Aft1p from its target promoters (v), leaving Aft1p available for nuclear export by Msn5p (vi). The expression of the iron regulon is thereby downregulated.

Grx3/4p participate in iron loading of several iron-containing proteins (26, 49). Grx3/4p may be involved in iron loading of Rnr2p, a cofactor of ribonucleotide reductase containing a di-iron center, together with Dre2p (49). Grx3/4p are also involved in the insertion of iron-sulfur clusters into cytosolic iron-sulfur-containing proteins such as Leu1p or Rli1p (26). Dre2p and Nbp35p, components of the cytoplasmic iron-sulfur assembly machinery, are also required for the insertion of iron-sulfur clusters (9, 30, 50). Although Nbp35p was identified as a candidate Aft1p-interacting protein by yeast two-hybrid screening (Fig. 3A), no significant interaction between Aft1p and Nbp35p was detected by coimmunoprecipitation, and Aft1p was normally regulated by iron in Nbp35p-depleted cells (data not shown). Moreover, suppression of Dre2p expression had no influence on iron-mediated suppression of expression of Aft1p target genes (data not shown). Thus, neither Nbp35p, consistent with earlier reports (41), nor Dre2p is required for suppression of Aft1p activity in iron-replete cells, while Grx3/4p are indispensable.

Fra1p and Fra2p are also involved in iron-mediated suppression of Aft1p activity (19). Both Fra1p and Fra2p bind to Grx3/4p (11, 21). Therefore, both proteins may function as a bridging molecule between Aft1p and Grx3p. However, no interactions between Aft1p and Fra1p or Fra2p have been detected, and both proteins are localized primarily in the cytosol (19), suggesting that either Fra1p or Fra2p is not involved in the Grx3/4p-mediated dissociation of Aft1p from target promoters. Grx5p, a mitochondrial monothiol glutaredoxin, is involved in storage and delivery of [2Fe-2S] clusters in the organelle (25, 38). Since forced expression of Grx3/4p in mitochondria partially rescues Grx5p function and growth defects of Δgrx5 mutants (24), one role of Grx3/4p may be to deliver iron-sulfur clusters. The activities of other metal-regulated transcriptional activators, Zap1p and Mac1p, are inhibited by the direct binding of zinc and copper (3, 13, 40), respectively. Direct metal binding may be the case with Aft1p as well. Aft1p forms homodimers or multimers in iron-rich cells, and Cys291 of Aft1p is involved in this interaction (44). In this study, Grx3p and Grx4p were shown to form homo- or heterodimers in an iron-dependent manner (Fig. 6). Considering that in vivo and in vitro analyses suggest that Grx3/4p dimerize through bridging a [2Fe-2S] cluster (26, 35), it is tempting to speculate that Grx3/4p dimers deliver iron, possibly an iron-sulfur cluster, to Aft1p at Cys291 and Cys293 to form iron-sulfur cluster-bridging Aft1p dimers. Alternatively, Aft1p may indirectly sense the cellular iron status through increased interactions with a [2Fe-2S] cluster-containing Grx3/4p dimer. Resolution of these complex interactions will require further biochemical and structural studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology in Japan to R.U. and K.I.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 October 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Askwith C, et al. 1994. The FET3 gene of S. cerevisiae encodes a multicopper oxidase required for ferrous iron uptake. Cell 76:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bedekovics T, Li H, Gajdos GB, Isaya G. 2011. Leucine biosynthesis regulates cytoplasmic iron-sulfur enzyme biogenesis in an Atm1p-independent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 286:40878–40888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bird AJ, et al. 2003. Zinc fingers can act as Zn2+ sensors to regulate transcriptional activation domain function. EMBO J. 22:5137–5146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boustany LM, Cyert MS. 2002. Calcineurin-dependent regulation of Crz1p nuclear export requires Msn5p and a conserved calcineurin docking site. Genes Dev. 16:608–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brachmann CB, et al. 1998. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14:115–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crisp RJ, et al. 2003. Inhibition of heme biosynthesis prevents transcription of iron uptake genes in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 278:45499–45506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. De Freitas J, et al. 2003. Yeast, a model organism for iron and copper metabolism studies. Biometals 16:185–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DeVit MJ, Johnston M. 1999. The nuclear exportin Msn5 is required for nuclear export of the Mig1 glucose repressor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Biol. 9:1231–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hausmann A, et al. 2005. The eukaryotic P loop NTPase Nbp35: an essential component of the cytosolic and nuclear iron-sulfur protein assembly machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:3266–3271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, Camaschella C. 2010. Two to tango: regulation of mammalian iron metabolism. Cell 142:24–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ho Y, et al. 2002. Systematic identification of protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry. Nature 415:180–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. James P, Halladay J, Craig EA. 1996. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144:1425–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jensen LT, Winge DR. 1998. Identification of a copper-induced intramolecular interaction in the transcription factor Mac1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 17:5400–5408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaffman A, Rank NM, O'Neill EM, Huang LS, O'Shea EK. 1998. The receptor Msn5 exports the phosphorylated transcription factor Pho4 out of the nucleus. Nature 396:482–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaplan CD, Kaplan J. 2009. Iron acquisition and transcriptional regulation. Chem. Rev. 109:4536–4552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kispal G, Csere P, Prohl C, Lill R. 1999. The mitochondrial proteins Atm1p and Nfs1p are essential for biogenesis of cytosolic Fe/S proteins. EMBO J. 18:3981–3989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kohrer K, Domdey H. 1991. Preparation of high molecular weight RNA. Methods Enzymol. 194:398–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Komeili A, O'Shea EK. 1999. Roles of phosphorylation sites in regulating activity of the transcription factor Pho4. Science 284:977–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kumanovics A, et al. 2008. Identification of FRA1 and FRA2 as genes involved in regulating the yeast iron regulon in response to decreased mitochondrial iron-sulfur cluster synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 283:10276–10286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leighton J, Schatz G. 1995. An ABC transporter in the mitochondrial inner membrane is required for normal growth of yeast. EMBO J. 14:188–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li H, et al. 2009. The yeast iron regulatory proteins Grx3/4 and Fra2 form heterodimeric complexes containing a [2Fe-2S] cluster with cysteinyl and histidyl ligation. Biochemistry 48:9569–9581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lill R. 2009. Function and biogenesis of iron-sulphur proteins. Nature 460:831–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Measday V, et al. 2005. Systematic yeast synthetic lethal and synthetic dosage lethal screens identify genes required for chromosome segregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:13956–13961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Molina MM, Belli G, de la Torre MA, Rodriguez-Manzaneque MT, Herrero E. 2004. Nuclear monothiol glutaredoxins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae can function as mitochondrial glutaredoxins. J. Biol. Chem. 279:51923–51930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Muhlenhoff U, Gerber J, Richhardt N, Lill R. 2003. Components involved in assembly and dislocation of iron-sulfur clusters on the scaffold protein Isu1p. EMBO J. 22:4815–4825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muhlenhoff U, et al. 2010. Cytosolic monothiol glutaredoxins function in intracellular iron sensing and trafficking via their bound iron-sulfur cluster. Cell Metab. 12:373–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Napier I, Ponka P, Richardson DR. 2005. Iron trafficking in the mitochondrion: novel pathways revealed by disease. Blood 105:1867–1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nehlin JO, Carlberg M, Ronne H. 1991. Control of yeast GAL genes by MIG1 repressor: a transcriptional cascade in the glucose response. EMBO J. 10:3373–3377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nehlin JO, Ronne H. 1990. Yeast MIG1 repressor is related to the mammalian early growth response and Wilms' tumour finger proteins. EMBO J. 9:2891–2898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Netz DJ, et al. 2010. Tah18 transfers electrons to Dre2 in cytosolic iron-sulfur protein biogenesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6:758–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ojeda L, et al. 2006. Role of glutaredoxin-3 and glutaredoxin-4 in the iron regulation of the Aft1 transcriptional activator in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 281:17661–17669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. O'Neill EM, Kaffman A, Jolly ER, O'Shea EK. 1996. Regulation of PHO4 nuclear localization by the PHO80-PHO85 cyclin-CDK complex. Science 271:209–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Papamichos-Chronakis M, Gligoris T, Tzamarias D. 2004. The Snf1 kinase controls glucose repression in yeast by modulating interactions between the Mig1 repressor and the Cyc8-Tup1 co-repressor. EMBO Rep. 5:368–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Philpott CC, Protchenko O. 2008. Response to iron deprivation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 7:20–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Picciocchi A, Saguez C, Boussac A, Cassier-Chauvat C, Chauvat F. 2007. CGFS-type monothiol glutaredoxins from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC6803 and other evolutionary distant model organisms possess a glutathione-ligated [2Fe-2S] cluster. Biochemistry 46:15018–15026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Protchenko O, et al. 2001. Three cell wall mannoproteins facilitate the uptake of iron in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 276:49244–49250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pujol-Carrion N, Belli G, Herrero E, Nogues A, de la Torre-Ruiz MA. 2006. Glutaredoxins Grx3 and Grx4 regulate nuclear localisation of Aft1 and the oxidative stress response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Sci. 119:4554–4564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rodriguez-Manzaneque MT, Tamarit J, Belli G, Ros J, Herrero E. 2002. Grx5 is a mitochondrial glutaredoxin required for the activity of iron/sulfur enzymes. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:1109–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rothstein R. 1991. Targeting, disruption, replacement, and allele rescue: integrative DNA transformation in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 194:281–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rutherford JC, Bird AJ. 2004. Metal-responsive transcription factors that regulate iron, zinc, and copper homeostasis in eukaryotic cells. Eukaryot. Cell 3:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rutherford JC, et al. 2005. Activation of the iron regulon by the yeast Aft1/Aft2 transcription factors depends on mitochondrial but not cytosolic iron-sulfur protein biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 280:10135–10140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shakoury-Elizeh M, et al. 2004. Transcriptional remodeling in response to iron deprivation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:1233–1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stearman R, Yuan DS, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Klausner RD, Dancis A. 1996. A permease-oxidase complex involved in high-affinity iron uptake in yeast. Science 271:1552–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ueta R, Fujiwara N, Iwai K, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y. 2007. Mechanism underlying the iron-dependent nuclear export of the iron-responsive transcription factor Aft1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 18:2980–2990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ueta R, Fukunaka A, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y. 2003. Pse1p mediates the nuclear import of the iron-responsive transcription factor Aft1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 278:50120–50127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Dancis A, Klausner RD. 1995. AFT1: a mediator of iron regulated transcriptional control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 14:1231–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Stearman R, Dancis A, Klausner RD. 1996. Iron-regulated DNA binding by the AFT1 protein controls the iron regulon in yeast. EMBO J. 15:3377–3384 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Ueta R, Fukunaka A, Sasaki R. 2002. Subcellular localization of Aft1 transcription factor responds to iron status in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18914–18918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang Y, et al. 2011. Investigation of in vivo diferric tyrosyl radical formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rnr2 protein: requirement of Rnr4 and contribution of Grx3/4 and Dre2 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 286:41499–41509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhang Y, et al. 2008. Dre2, a conserved eukaryotic Fe/S cluster protein, functions in cytosolic Fe/S protein biogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:5569–5582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]