Abstract

The symbiosis polysaccharide locus, syp, is required for Vibrio fischeri to form a symbiotic association with the squid Euprymna scolopes. It is also required for biofilm formation induced by the unlinked regulator RscS. The syp locus includes 18 genes that can be classified into four groups based on putative function: 4 genes encode putative regulators, 6 encode glycosyltransferases, 2 encode export proteins, and the remaining 6 encode proteins with other functions, including polysaccharide modification. To understand the roles of each of the 14 structural syp genes in colonization and biofilm formation, we generated nonpolar in-frame deletions of each gene. All of the deletion mutants exhibited defects in their ability to colonize juvenile squid, although the impact of the loss of SypB or SypI was modest. Consistent with their requirement for colonization, most of the structural genes were also required for RscS-induced biofilm formation. In particular, the production of wrinkled colonies, pellicles, and the matrix on the colony surface was eliminated or severely decreased in all mutants except for the sypB and sypI mutants; in contrast, only a subset of genes appeared to play a role in attachment to glass. Finally, immunoblotting data suggested that the structural Syp proteins are involved in polysaccharide production and/or export. These results provide important insights into the requirements for the syp genes under different environmental conditions and thus lay the groundwork for a more complete understanding of the matrix produced by V. fischeri to enhance cell-cell interactions and promote symbiotic colonization.

INTRODUCTION

The initial interactions between microbes and their hosts are critical to the establishment of both symbiotic and pathogenic associations. The adherence of the microbe to its host and bacterial cell-cell aggregation are two processes that can mediate these initial interactions. The roles of polysaccharides in promoting adherence and cell-cell interactions in pathogenic and symbiotic colonization are well recognized (29, 37). Bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS), for example, can mediate the adherence of bacterial cells to various cellular components, such as mannose receptors and mucus (17, 34). Capsular polysaccharides (CPS) and/or exopolysaccharides (EPS), present on the bacterial surface and secreted, respectively, can promote adherence to host or abiotic surfaces by facilitating the formation of biofilms and thus increasing colonization efficiency (4).

To understand bacterium-host and bacterium-bacterium interactions during the colonization of a host, we have used the symbiosis between the bacterium Vibrio fischeri and its host, the squid Euprymna scolopes, as a model system (30). We previously obtained evidence that one or more polysaccharides are important for the ability of V. fischeri to colonize its host (5, 36, 49, 50). In particular, V. fischeri depends upon the 18-gene symbiosis polysaccharide (syp) locus for efficient colonization: the insertional mutation of several syp genes reduced colonization by about 1,000-fold (50). Furthermore, colonization was enhanced through the upregulation of the syp genes by overexpression from a plasmid of an unlinked regulator, the sensor kinase RscS (pRscS+) (11, 42, 49): experiments in which pRscS+ cells competed with vector control cells resulted in the squid being colonized exclusively by the pRscS+ strain (49). These results appear to be explained by a massive increase in the adherence of the pRscS+ strain to the surface of the squid's symbiotic organ relative to that of the control. Consistent with its ability to enhance colonization and promote biologically relevant adherence, the overproduction of RscS induced biofilm phenotypes in culture that depended on at least one syp structural gene, sypN (49). These in vitro phenotypes included increased attachment to glass, the production of strong pellicles at liquid culture surfaces, the formation of wrinkled colonies on solid media, and the production of an extracellular matrix visible by electron microscopy (49). Furthermore, pRscS+ cells released outer membrane vesicles that had antigenically distinct Syp-dependent molecules, potentially Syp-modified LPS, on their surfaces in addition to normal LPS molecules (36).

The 18 genes that comprise the syp gene cluster, sypA to sypR, are oriented in the same direction and appear to be grouped into at least four operons (50) (Fig. 1). Of these genes, four are predicted to encode regulatory proteins. (i) SypG is a response regulator that is required for phenotypes induced by pRscS+, including syp transcription and biofilm formation; it is predicted to be the direct transcriptional activator of the syp locus (16, 50). (ii) SypE is a second response regulator, which appears to play both positive and negative roles in biofilm formation (16, 27). (iii) SypF, a predicted sensor kinase, also influences biofilm formation (5). (iv) SypA exhibits similarity to anti-sigma factor antagonists. Such proteins play positive regulatory roles in other systems (28, 41).

Fig 1.

Genetic organization of the syp gene locus. The 18 genes in the syp cluster are represented by block arrows. Predicted regulatory genes are indicated by white arrows, predicted glycosyltransferase genes are indicated by gray filled arrows, predicted export genes are indicated by hatched-line filled arrows, and other genes related to polysaccharide modification or chain length regulation are indicated by black arrows. Known promoters are represented by black-line arrows, while a potential promoter is represented by a dashed-line arrow.

The remaining 14 genes are predicted to encode structural proteins involved in polysaccharide production, modification, and export (50). Previously, we demonstrated that insertional mutations in the structural genes sypC, sypD, sypJ, sypL, sypN, sypO, sypP, sypQ, and sypR resulted in defects in symbiotic colonization (50) and that RscS-induced formation of wrinkled colonies and pellicles depended upon the presence of sypN (49). However, these mutations likely exert polar effects on downstream genes. Furthermore, the roles of five structural genes (sypB, sypH, sypI, sypJ, and sypK) in colonization and biofilm formation (except for sypK [36]) have not been examined. Thus, to better understand the requirements for individual structural syp genes, we constructed in-frame, nonpolar deletions of each of the structural syp genes and evaluated the phenotypes of the resulting mutants in symbiotic colonization, biofilm formation, and polysaccharide production. These studies permitted us to determine which genes were critical to symbiosis and which phenotypes observed in culture were most predictive of a colonization defect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

V. fischeri and Escherichia coli strains constructed and/or used in this study are listed in Table 1. V. fischeri strain ES114 (2) was used as the wild-type strain in these studies. V. fischeri strains were grown in LBS (12), HEPES minimal medium (HMM) containing 0.3% Casamino Acids and 0.2% glucose (35), or SWT (50). E. coli strains were grown in LB (6). The following antibiotics were added, as appropriate, at the following final concentrations: chloramphenicol (Cm) at 1 to 5 μg/ml (V. fischeri) or 12.5 to 25 μg/ml (E. coli); ampicillin (Ap) at 100 μg/ml (E. coli); and tetracycline (Tc) at 5 μg/ml for LBS (V. fischeri), 30 μg/ml for HMM (V. fischeri), or 15 μg/ml (E. coli). Thymidine was added to a final concentration of 0.3 mM to grow E. coli π3813 cells, and 2,6-diaminopimelic acid (DAP) was added to a final concentration of 0.3 mM to grow E. coli β3914 cells. Agar was added to a final concentration of 1.5% for solid media.

Table 1.

Strains used in this work

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| TAM1 | mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) ϕ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araΔ139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL endA1 nupG | Active motif |

| π3813 | lacIq thi-1 supE44 endA1 recA1 hsdR17 gyrA462 zei-298::Tn10 ΔthyA::(erm-pir) (Emr Tcr) | 19 |

| β3914 | F− RP4-2-Tc::Mu ΔdapA::(erm-pir) gyrA462 zei-298::Tn10 (Kmr Emr Tcr) | 19 |

| CC118λpir | Δ(ara-leu) araD Δlac74 galE galK phoA20 thi-1 rpsE rpsB argE(Am) recA λpir | 13 |

| V. fischeri | ||

| ES114 | Wild type | 2 |

| KV5044 | ΔsypP | This study |

| KV5067 | ΔsypD | This study |

| KV5068 | ΔsypI | This study |

| KV5069 | ΔsypL | This study |

| KV5097 | ΔsypK | 36 |

| KV5098 | ΔsypN | This study |

| KV5099 | ΔsypQ | This study |

| KV5145 | ΔsypB | This study |

| KV5146 | ΔsypO | This study |

| KV5192 | ΔsypC | This study |

| KV5193 | ΔsypH | This study |

| KV5194 | ΔsypM | This study |

| KV5195 | ΔsypR | This study |

| KV5664 | ΔsypJ | This study |

Construction of in-frame deletion mutants.

The plasmids and primers used in this study are listed in Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material, respectively. The syp deletion mutants were generated as follows. Primers were designed to generate in-frame deletions of the syp genes, leaving a short, nonnative sequence in place of each syp gene. The primers were used in PCRs that amplified DNA sequences upstream and downstream of each of the target syp genes from the ES114 chromosome. These flanking sequences were joined by using overlap-extension PCR (14). Each resulting DNA fragment was cloned into a PCR cloning plasmid (pJET1.2; Fermentas) and then subcloned into a mobilizable suicide vector (pKV363 or pSW7848) by using the appropriate restriction enzymes and introduced into either E. coli strain π3813 or β3914. To transfer the plasmids into V. fischeri, triparental conjugations were performed by using π3813 carrying pEVS104 (7, 38). We then used a gene replacement protocol described previously by Le Roux et al. (19) and screening by PCR to obtain and verify the deletion mutants.

Colonization assay.

Strains used in the colonization assay were grown in SWT for 3 h at 28°C before inoculation. Bacterial cells were then inoculated into artificial seawater (ASW) (Instant Ocean; Aquarium Systems, Mentor, OH) at a concentration of 2,000 to 5,000 cells per ml. Newly hatched juvenile squid were then introduced into the V. fischeri-containing seawater. At 18 h postinoculation, animals were washed, placed into 70% ASW (100 mM MgSO4, 20 mM CaCl2, 0.6 M NaCl, 20 mM KCl), and then homogenized. Serial dilutions of the homogenates were plated onto SWT agar, and the number of CFU was calculated. The statistical significance (P value) was determined by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's multiple-comparisons test, performed by using GraphPad software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

Complementation.

Plasmids to complement the syp deletion mutants were generated by using PCR and specific primers listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. The vector for these complementation plasmids, pVSV105 (9), is compatible with plasmid pARM7 (27), which carries the rscS gene. Thus, to complement the syp deletions, we introduced both pARM7 and the pVSV105-based syp-containing plasmids into the appropriate syp deletion strain. As controls, we introduced pARM7 and the pVSV105 vector into each of the syp deletion mutants. These strains were grown in the presence of Cm and Tc to select for the two plasmids and assayed for the formation of wrinkled colonies and pellicles.

Wrinkled colony assays.

For wrinkled colony assays, strains were grown overnight at 28°C in LBS liquid medium containing Tc and then subcultured for 4 h. Subcultures were adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3, and 10-μl aliquots were spotted onto Tc-containing LBS (LBS-Tc) plates. The plates were incubated at room temperature for 48 h before the resulting colonies were photographed by using a Zeiss Stemi 2000-C dissecting microscope with a camera attachment (ProgRES C10PLUS).

Pellicle assay.

For pellicle assays, strains were grown overnight in HMM with Tc. The cells were then diluted to an OD600 of about 0.1 in 2 ml of HMM with Tc. This suspension was transferred into the wells of a 24-well microtiter plate (BD Falcon). The plates were incubated for 48 h at room temperature. The thickness of each pellicle was evaluated based on its resistance to disruption with a pipette tip. Pellicle thickness was scored as follows: cultures with strong, cohesive pellicles that could be peeled from the culture intact by using manual pressure were scored as “++”; intermediate/weak pellicles that could be observed as a very thin and fragile film structure were scored as “+”; and the absence of any surface-localized cellular material was scored as “−.”

Adherence to glass.

The ability of V. fischeri to adhere to glass was quantified by using a modified crystal violet assay, as described previously (50). Briefly, V. fischeri strains were grown in triplicate in HMM containing Tc. Cultures grown overnight were diluted with fresh medium to an OD600 of about 0.1, and 3 ml of culture was then incubated in borosilicate glass tubes (13 by 100 mm), without shaking, for 48 h at room temperature. To quantify attachment to glass, a 300-μl aliquot of 1% crystal violet was added to each culture. After 20 min of staining, the liquid was removed from the tubes, and each test tube was rinsed with distilled water (dH2O). To destain the crystal violet, a 4-ml aliquot of 100% ethanol was added to each test tube. Samples were destained by vortexing for 3 min. We quantified the staining by measuring the OD600.

Isolation of polysaccharide from V. fischeri cells and immunoblotting analysis.

Lipopolysaccharides were isolated from V. fischeri cells by using a modified hot phenol-water method (7, 36). Strains were grown in LBS with Tc at 23°C for 18 h. Aliquots (1.5 ml) of the cell cultures were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min, and the cell pellets were washed with 70% ASW. The pellets were resuspended in 300 μl of a solution containing 5 mM EDTA and 50 mM sodium phosphate, dibasic. A 300-μl aliquot of saturated phenol was then added, and the samples were incubated at 65°C for 15 min. Samples were placed on ice for 5 min and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The aqueous phase from each sample was removed, passaged through a MicroSpin G-25 column (GE Healthcare, United Kingdom), and then lyophilized. To detect Syp-dependent polysaccharides (Syp-polysaccharides), samples were analyzed by using SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with biofilm-specific antibodies (36). Briefly, these antibodies were generated by injecting rabbits with pRscS+ cells from biofilms (cells from wrinkled colonies), and the resulting antiserum was adsorbed against nonbiofilm (wild-type) cells. This process yielded antibodies that specifically detected molecules produced by Syp biofilm-producing cells (pRscS+) not present in non-biofilm-producing cells (36).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Strains were grown overnight in Tc-containing LBS and then subcultured. The cultures were then adjusted to an OD600 of 0.3 and spotted onto dialysis membranes (nominal molecular weight cutoff [MWCO] of 6,000 to 8,000; Fisher Scientific) which were placed onto LBS-Tc plates. The plates were incubated for 48 h at room temperature. After incubation, the dialysis membranes were removed from the plates and cut to separate the individual colonies. The colonies on the membranes were fixed overnight in a solution containing 1.2% glutaraldehyde, 0.45 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3), and 0.1% (wt/vol) ruthenium red. After fixation, the samples were washed, postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h, and washed again with cacodylate buffer. The samples were dehydrated through ethanol and embedded in resin. The thin-sectioned samples were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Finally, the samples were examined with a transmission electron microscope (Hitachi H-600) operating at an accelerating voltage of 75 kV.

Identification and deletion of SypC's putative signal sequence.

SignalP 4.0 (31) was used to identify a putative signal peptide in SypC. This program predicted cleavage after amino acid 21 (Ala) of SypC. Therefore, to determine the role played, if any, by the putative signal sequence, we generated derivatives in which SypC's ATG start codon was fused to codon 22. Specifically, we generated constructs (pKV480 to pKV483) in which the C terminus was fused to either the FLAG or hemagglutinin (HA) epitope and which contained either the N-terminal deletion or wild-type sequences. We then assessed the ability of SypC expressed from these plasmids to complement the pARM7-containing (RscS-overexpressing) ΔsypC mutant for the formation of wrinkled colonies.

RESULTS

Bioinformatic analysis of structural syp genes.

Within the V. fischeri syp locus, 14 genes appear to encode structural proteins that may be involved in the export, synthesis, or modification of one or more polysaccharides (Fig. 1). To gain a better appreciation for the putative roles of these structural Syp proteins, we analyzed the proteins using blastp, which is based on the DELTA-BLAST (Domain-Enhanced Lookup Time-Accelerated BLAST) algorithm (22–24). This algorithm emphasizes the domain structure of the proteins, which is beneficial, as the Syp proteins have relatively low sequence identities to characterized proteins involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis and export. These analyses permitted us to group the proteins into 3 classes, glycosyltransferases (GTs), polysaccharide exporters, and “other” (Table 2).

Table 2.

Putative functions and roles of structural Syp proteins

| Locus tag | Protein designation | Size (amino acids) | Putative function (homologous protein)a | Symbiotic colonizationb | Formation of wrinkled coloniesc | Pellicle formationd | Glass attachmente | Matrix productionf | Syp-polysaccharide production or antigenicityg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VF_A1027 | SypH | 338 | Glycosyltransferase 1 | − | − | + | + | Swollen | − |

| VF_A1028 | SypI | 424 | Glycosyltransferase 1 | +/− | P | ++ | + | + | + |

| VF_A1029 | SypJ | 387 | Glycosyltransferase 1 | − | − | + | ++ | Swollen | − |

| VF_A1033 | SypN | 378 | Glycosyltransferase 1 | − | − | + | ++ | Swollen | − |

| VF_A1035 | SypP | 362 | Glycosyltransferase 1 | − | − | + | ++ | Swollen | − |

| VF_A1036 | SypQ | 395 | Glycosyltransferase 2 | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| VF_A1022 | SypC | 703 | Polysaccharide exporter (Wza) | − | − | + | ++ | − | + |

| VF_A1030 | SypK | 480 | O-antigen unit translocase or flippase (RfbX/Wzx) | − | − | − | + | Swollen | − |

| VF_A1021 | SypB | 274 | Regulator of cellulose production (OmpA) | +/− | P | ++ | + | + | + |

| VF_A1023 | SypD | 235 | Chain length determinant protein tyrosine kinase (EpsG/Wzc) | − | − | + | ++ | − | + |

| VF_A1031 | SypL | 461 | Lipid A core–O-antigen ligase (RfaL/WaaL) | − | − | + | ++ | − | P |

| VF_A1032 | SypM | 251 | Sugar O-acetyltransferase | − | − | + | ++ | Swollen | P |

| VF_A1034 | SypO | 499 | Chain length determinant protein (Wzz) | − | − | + | ++ | Swollen | + |

| VF_A1037 | SypR | 214 | Undecaprenyl-phosphate galactose phosphotransferase (WbaP) | − | − | + | ++ | − | P |

Symbiotic colonization ability slightly (+/−) or severely (−) decreased compared to that of the wild type.

Formation of partially wrinkled (P) or smooth (−) colonies.

Strong pellicle formation similar to that of the wild type (++), weak pellicle formation (+), or no pellicle formation (−).

Glass attachment ability more than 3-fold increased (++) or 2- to 3-fold increased (+) relative to that of the vector control.

+, colony has a membrane-like matrix on the surface; −, colony has no matrix (−); Swollen, cells with a swollen-cell phenotype.

+, mutant cells produced Syp-polysaccharides with an antigenicity similar to that of the wild type; Partial, the detected Syp-polysaccharide lost the predicted O-antigen structure; −, no molecules were detected.

Of the 14 predicted structural proteins, six are putative GTs, enzymes that transfer sugar from an activated donor to a recipient polysaccharide chain. Of these proteins, five (SypH, SypI, SypJ, SypN, and SypP) contain domains that are conserved in the glycosyltransferase 1 family of proteins: SypH contains a GT1_YqgM_like domain (cd03801; E value of 8E−36), SypI contains a GT1_YqgM_like domain (cd03801; E value of 4E−59), SypJ contains a GT1_YqgM_like domain (cd03801; E value of 2E−08), SypN contains a GT1-like_1 domain (cd04950; E value of 1E−64), and SypP contains a GT1_WbnK_like domain (cd03807; E value of 8E−64). The remaining GT protein, SypQ, contains a domain that is conserved in the structurally distinct glycosyltransferase 2 family of proteins, the CESA_like_1 domain (cd06439; E value of 5.05E−99).

Two of the Syp proteins are putative polysaccharide exporters: SypC contains the Wza domain (COG1596; E value of 2E−16) that is found in the Wza protein family; Wza in E. coli is involved in translocation to the surface of group 1 and 4 capsular polysaccharides (45). SypK contains the conserved domain RfbX (COG2244; E value of 1E−11) that is found in O-antigen unit translocases and the flippase protein RfbX (Wzx), which is responsible for the transfer of polysaccharide from the cytoplasmic side to the periplasmic side of the cytoplasmic membrane (20).

The remaining six proteins have putative functions related to polysaccharide modification or chain length regulation. In its C-terminal region, SypB contains an OmpA_C-like domain (cd07185; E value of 4E−22), which is a putative peptidoglycan binding domain similar to the C-terminal domain of the outer membrane protein OmpA. SypD contains the EpsG domain (TIGR03229; E value of 2.89E−08), which is conserved in the chain length determinant protein EpsG, a protein found in a Methylobacillus sp. that is similar to the chain length regulator Wzc of E. coli (51). SypL contains the RfaL domain (COG3307; E value of 2E−07), which is conserved in the lipid A core–O-antigen ligase RfaL (WaaL) (25). SypM contains the LbH_MAT_GAT domain (cd03357; E value of 5E−26), which is found in sugar O-acetyltransferases. SypO contains a Wzz domain (pfam02706; E value of 1.38E−03), a domain that is conserved in the Wzz superfamily; members of this family control polysaccharide chain length (45). SypR contains the WbaP_sugtrans domain (TIGR03022; E value of 2E−4), a domain that is conserved in the undecaprenyl-phosphate galactose phosphotransferase WbaP, a protein that forms part of a glycosyltransferase complex involved in the earliest step of O-antigen biosynthesis in Salmonella enterica (43).

Colonization by syp deletion mutants.

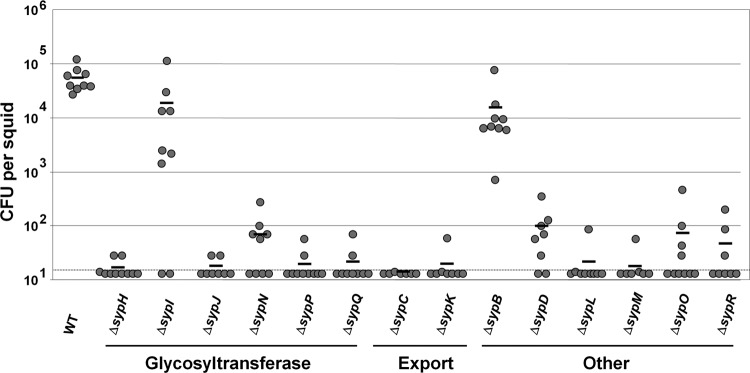

To understand the roles of the Syp structural proteins in host colonization, we first generated in-frame deletions of each of the 14 genes. We then evaluated the impact of these mutations on the growth of V. fischeri and found that they did not impact its growth in the complex medium LBS or the minimal medium HMM (data not shown). Next, we used these strains to inoculate uncolonized juvenile squid and assessed colonization levels at 18 h postinoculation. Five of the six GT mutants (ΔsypH, ΔsypJ, ΔsypN, ΔsypP, and ΔsypQ), both export mutants (ΔsypC and ΔsypK), and five of the six mutants in the “other” group (ΔsypD, ΔsypL, ΔsypM, ΔsypO, and ΔsypR) exhibited severe defects in their ability to colonize juvenile squid (Fig. 2). In contrast, the ΔsypI and ΔsypB mutants (encoding putative GT and peptidoglycan binding proteins, respectively) were able to colonize. However, their level of colonization was approximately 3-fold lower than that of the wild type, suggesting that SypI and SypB are required for efficient symbiotic colonization (Fig. 2). These data suggest that all of the structural Syp proteins are important for normal symbiotic colonization by V. fischeri.

Fig 2.

Symbiotic colonization by syp deletion mutant strains. Newly hatched juvenile E. scolopes squid were inoculated for approximately 18 h with the wild type (WT) or syp deletion mutant strains and subsequently homogenized. Bacterial numbers were assessed by plating and are indicated as CFU per squid. Each circle represents CFU from an individual squid. The black bar indicates the average CFU. The dashed line indicates the limit of detection (14 CFU). The data shown are combined data from two experiments. In all cases, the P values for the syp mutants relative to the wild type are <0.01.

Formation of wrinkled colonies on solid medium.

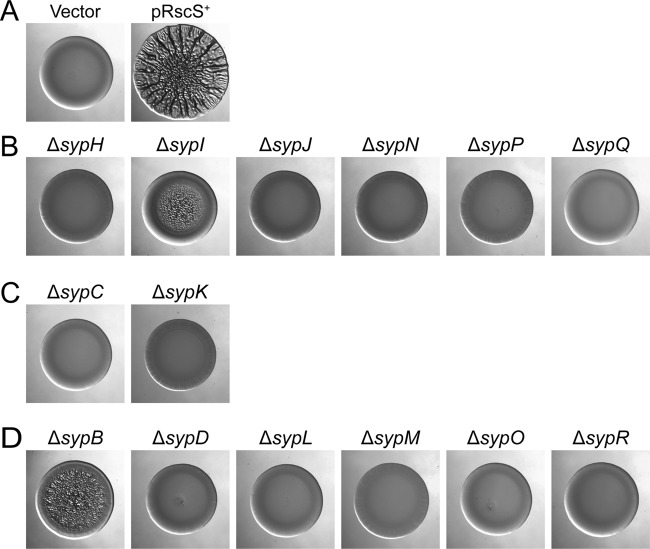

The first step in determining the mechanism of action of these proteins is to identify what phenotypes are displayed by the mutants in culture and to ask which phenotypes, if any, correlate in their severity to those observed in symbiosis. An obvious phenotype to evaluate was biofilm formation. V. fischeri cells do not form substantial biofilms in culture unless a regulatory protein, such as the sensor kinase RscS, is overexpressed. Therefore, we first introduced either the RscS overexpression plasmid pARM7 (here referred to as pRscS+ for simplicity) or the vector control plasmid pKV282 into the wild-type control strain and each deletion mutant. One assay of biofilm formation is the development of wrinkled colonies (3, 48). To assess this phenotype, we spotted liquid cultures of the strains onto LBS, a complex solid medium, and examined the morphology of the resulting colonies. As observed previously, wild-type cells containing pRscS+ formed wrinkled colonies with a complex three-dimensional (3-D) structure, whereas the empty vector control strain formed smooth colonies (Fig. 3A) (27, 49).

Fig 3.

Formation of wrinkled colonies by rscS-overexpressing syp mutant strains. Wild-type and syp deletion mutant strains overexpressing rscS (or carrying the vector control) were grown in Tc-containing LBS liquid medium and then spotted onto LBS-Tc plates at room temperature. The formation of wrinkled colonies was assessed at 48 h postspotting. These strains are grouped as follows: wild-type controls (wild-type strain carrying the control vector pKV282 [Vector] or rscS-overexpressing plasmid pARM7 [pRscS+]) (A), pARM7-containing glycosyltransferase mutants (B), polysaccharide export mutants (C), and other mutants (D). Images are representative of three independent experiments.

In contrast to the pRscS+ wild-type cells, the mutants exhibited defects in the formation of wrinkled colonies. Consistent with their severe defects in symbiotic colonization, five of the six GT mutants (ΔsypH, ΔsypJ, ΔsypN, ΔsypP, and ΔsypQ) (Fig. 3B), both of the export mutants (ΔsypC and ΔsypK) (Fig. 3C), and five of the six other mutants (ΔsypD, ΔsypL, ΔsypM, ΔsypO, and ΔsypR) (Fig. 3D) formed colonies that were indistinguishable from the smooth colonies formed by the vector control at 48 h postspotting (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the ΔsypB and ΔsypI mutants, which exhibited less-severe defects in colonization, similarly exhibited less-severe defects in the development of wrinkled colonies: whereas the spots of the control strain exhibited wrinkling within 20 h, those of the sypB and sypI mutants were smooth at that time (data not shown). However, the mutant morphology did not remain smooth: within 48 h, the mutant spots exhibited a partially wrinkled morphology, with the outer edge of the colony remaining smooth (Fig. 3B and D). Thus, the loss of sypB or sypI both delayed and diminished wrinkled colony development, but neither gene was essential for this phenotype. In all cases, mutant cells carrying the vector control formed smooth colonies (data not shown). To confirm that the deletions did not exert polar effects on downstream genes, we generated complementation plasmids carrying each missing gene (with two exceptions; we were unable to obtain plasmids carrying either sypB or sypO) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). We introduced the appropriate plasmid into each deletion mutant along with pRscS+. Each deletion mutant was able to be complemented to robust wrinkled colony formation by the expression of the missing gene (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), suggesting that the deletions are not polar. These data demonstrate that all of the structural syp genes (and not just sypN [49]) are required for the development of wrinkled colonies, although sypB and sypI play a lesser role. Thus, the ability of a mutant to form wrinkled colonies correlates well with its ability to initiate symbiotic colonization.

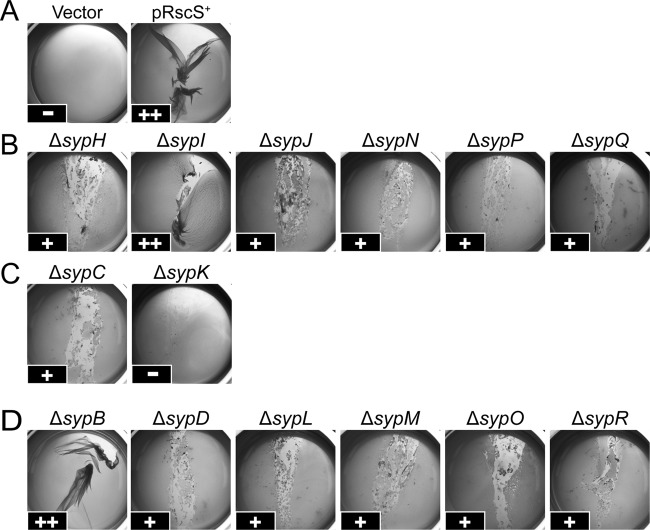

Pellicle formation at the air-liquid interface.

A second phenotype induced by pRscS+ is the formation of pellicles at the air-liquid interface by cells grown under static conditions in the minimal medium HMM. We analyzed the ability of the pRscS+ syp deletion mutants to form pellicles under these conditions. To make this phenotype semiquantitative, we estimated the strength of the pellicles by disturbing the air-liquid interface with a pipette tip. The resulting disruptions to the surface can be observed in Fig. 4. Under these conditions, vector control cells did not form pellicles (scored as −), and pRscS+ wild-type cells produced a pellicle that was very cohesive and could be peeled from the culture intact by using manual pressure (scored as ++) (Fig. 4A). Consistent with their modest impact on the formation of wrinkled colonies, sypI and sypB mutants formed pellicles that did not differ greatly from those produced by pRscS+ wild-type cells (scored as ++) (Fig. 4B and D). In contrast, the rest of the deletion mutants formed a weak pellicle that was thin and could be easily disrupted relative to that formed by pRscS+ wild-type cells (scored as +) (Fig. 4B to D). One exception was the ΔsypK mutant, which completely lost its ability to form a pellicle (scored as −) (Fig. 4C). This was the only mutation that completely abrogated pellicle formation. In all cases, the deletion mutants carrying only the vector produced no pellicle (data not shown). Pellicle production could be restored by the introduction of the respective complementing plasmid, although for a couple of mutants (sypC and sypQ), the pellicles were not as strong as those produced by the wild-type control (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Because all of the deletion mutants, except for ΔsypK, retained the ability to form a weak pellicle, these data suggest that these structural Syp proteins are involved in strong pellicle formation but are not essential for basal pellicle formation. Thus, either there is a redundancy in function for this phenotype or another non-Syp component(s) contributes to the establishment of the basal pellicle formed under pRscS+ conditions.

Fig 4.

Pellicle formation at the liquid-air interface by rscS-overexpressing syp mutant strains. The wild-type and syp deletion mutant strains overexpressing rscS (or carrying the vector control) were incubated statically in Tc-containing HMM at room temperature for 48 h. These strains are grouped as follows: wild-type controls (wild-type strain carrying the control vector pKV282 [Vector] or rscS-overexpressing plasmid pARM7 [pRscS+]) (A), pARM7-containing glycosyltransferase mutants (B), polysaccharide export mutants (C), and other mutants (D). Pellicle formation was assessed by disrupting the surface of the air-liquid interface with a pipette tip. The approximate strength of the pellicle was scored as follows: a strong pellicle that was able to be peeled away from the culture was scored as ++, an intermediate/weak pellicle that was easily disrupted was scored as +, and the absence of a pellicle was scored as −. Images are representative of three independent experiments.

Glass attachment.

RscS overexpression also promotes the ability of V. fischeri to attach to a glass surface (49). To understand the roles of the structural Syp proteins in this ability, we used a crystal violet staining assay to visualize and quantify cellular material on the test tube surface (see Materials and Methods) following the growth of our strains in HMM under static conditions. Consistent with data from previous reports, pRscS+ wild-type cells showed approximately a 4-fold-increased attachment to glass relative to that of vector-containing wild-type cells (Fig. 5A and E). Under pRscS+ conditions, only the ΔsypC and ΔsypJ mutants exhibited a similar ability to attach (approximately 4- to 4.5-fold-increased attachment relative to that of vector-containing wild-type cells) (Fig. 5B, C, and E). However, the defects of the other mutants were relatively moderate: all the other mutants retained an increased ability to attach to glass relative to that of control cells (2- to 3-fold increase relative to vector-containing wild-type cells) (Fig. 5E). Surprisingly, although the ΔsypK mutant completely lost the ability to form wrinkled colonies and pellicles, it still exhibited approximately a 2-fold-increased ability to attach to a glass surface relative to that of the control (Fig. 5C and E). Thus, no clear correlation can be made between the ability to attach to a glass surface and either the ability to promote other biofilm phenotypes, such as the formation of wrinkled colonies and pellicles, or the ability to establish symbiotic colonization.

Fig 5.

Glass surface attachment by rscS-overexpressing syp mutant strains. The abilities of the rscS-overexpressing wild-type and syp deletion mutant strains to attach to a glass surface were assessed by using a crystal violet assay following 48 h of static growth in Tc-containing HMM at room temperature. (A to D) Crystal violet-stained glass tubes are grouped as follows: wild-type controls (wild-type strain carrying the control vector pKV282 [Vector] or rscS-overexpressing plasmid pARM7 [pRscS+]) (A), pARM7-containing glycosyltransferase mutants (B), polysaccharide export mutants (C), and other mutants (D). (E) Quantification of crystal violet staining. The experiment was performed in triplicate, and representative results are shown. Each bar represents the fold difference relative to the values for the vector control wild-type strain. The error bars indicate the standard deviations.

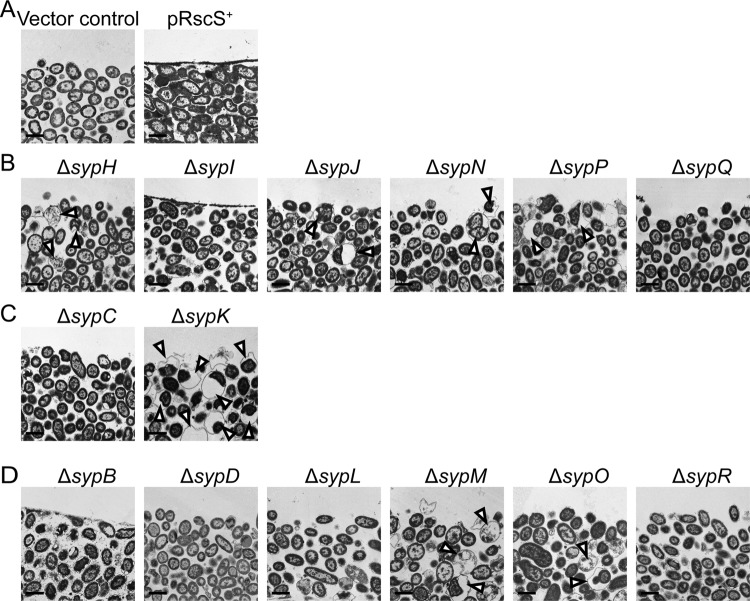

Production of a biofilm matrix on the colony surface.

Our previous TEM data revealed that wrinkled colonies formed by pRscS+ wild-type cells contained an extracellular matrix that could be detected as a thick (electron-dense) layer at the colony surface (49). To evaluate the role(s) of the structural Syp proteins in the production of the surface matrix, the colonies of pRscS+ syp deletion mutants and controls were fixed and stained with ruthenium red, uranyl acetate, and lead citrate and then examined by using TEM. As observed previously, the pRscS+ wild-type colonies contained a thick layer at the colony surface (visualized as a dark line at the top of the cells) that was lacking in vector control cells (Fig. 6A). Consistent with their ability to form wrinkled colonies, albeit with diminished 3-D architecture at 48 h after spotting, the ΔsypB and ΔsypI deletion mutants each produced an apparently normal biofilm matrix on their colony surface (Fig. 6B and D). In contrast, the rest of the deletion mutants failed to produce a detectable matrix at the colony surface (Fig. 6B to D). These results generally indicated a correlation between wrinkled-colony morphology and biofilm matrix production. Intriguingly, our TEM data also revealed aberrant cell morphologies for several of the deletion mutants (sypK, sypH, sypJ, sypN, sypP, sypM, and sypO). A number of cells located toward the surface of the colonies formed by these strains were surrounded by a membrane-like structure encompassing a normal-sized cytoplasm and a broad region of low electron density (Fig. 6B to D, arrowheads). We have termed this phenotype the “swollen-cell” phenotype. In particular, the ΔsypK mutant exhibited a remarkable increase in the number of cells with this swollen phenotype; we observed that approximately 35% of cells at or near the surface of the colony exhibited the swollen morphology. In contrast, in the region at or near the bottom of the colony, the cells were packed tightly, and very few swollen cells were apparent (less than 1%) (data not shown). These observations suggested that, perhaps, the activity of Syp-polysaccharide production is spatially regulated, with it being greater at the colony surface than at or near the bottom of the colony.

Fig 6.

TEM analysis of colonies formed by rscS-overexpressing syp mutant strains. Colonies of rscS-overexpressing wild-type or syp mutant strains were fixed and stained with ruthenium red, uranyl acetate, and lead citrate and then visualized by using TEM. These strains are grouped as follows: wild-type controls (wild-type strain carrying the control vector pKV282 [Vector] or rscS-overexpressing plasmid pARM7 [pRscS+]) (A), pARM7-containing glycosyltransferase mutants (B), polysaccharide export mutants (C), and other mutants (D). The bars represent 2 μm. Images are representative of two independent experiments. Open arrowheads indicate the locations of cells with the “swollen-cell” phenotype.

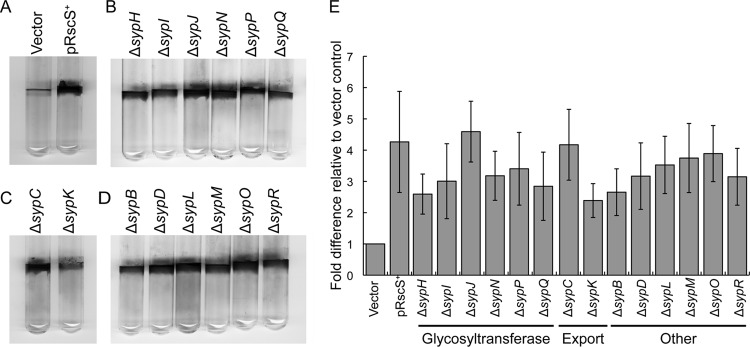

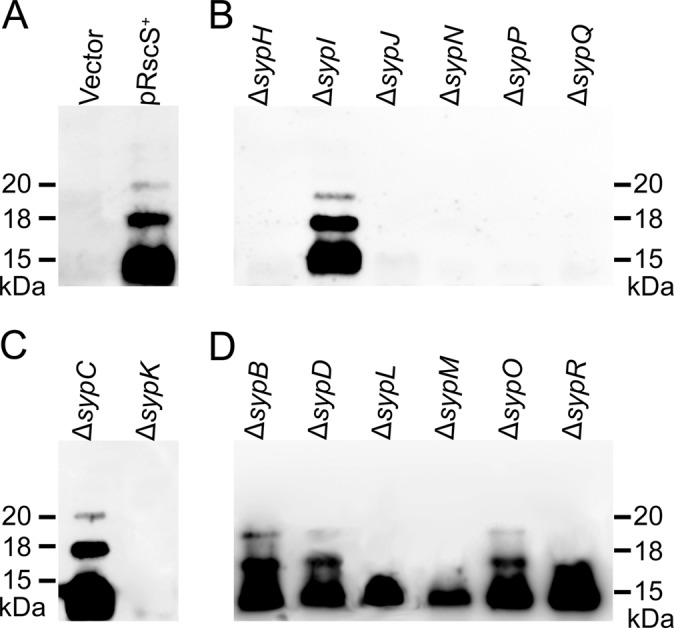

Production of Syp-dependent polysaccharides.

In a previous study describing the production of outer membrane vesicles by V. fischeri, we generated biofilm-specific antibodies that could detect nonproteinaceous, Syp-dependent molecules (see Materials and Methods) (36). Furthermore, we demonstrated that these molecules could be obtained by using procedures which extracted LPS molecules and that their production occurred only when RscS was overexpressed (36). Finally, we found that the deletion of the putative oligosaccharide translocase gene sypK resulted in the loss of the production or detection of these molecules (36). These results suggested that our antibodies recognized Syp-produced polysaccharides, potentially modified LPS. We therefore wondered whether the deletion of other structural syp genes would also affect the production and/or modification of these Syp-polysaccharide molecules. To evaluate the roles of the Syp proteins, we used our LPS extraction protocol to obtain Syp-polysaccharides from the pRscS+ syp deletion mutants. These molecules were separated by using SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting using the biofilm-specific antibodies. As previously observed, molecules with apparent molecular masses of 15, 18, and 20 kDa were detected in LPS extractions from pRscS+ wild-type cells by immunoblot analysis and not in LPS fractions from either vector control wild-type cells or pRscS+ ΔsypK mutant cells (Fig. 7A and C). These molecules also appeared to be absent in the LPS fractions from the five biofilm-defective GT mutants (Fig. 7B). Consistent with their weak defects in symbiotic colonization and biofilm formation, both the sypI and sypB mutants produced Syp-polysaccharides with a migration pattern and antigenicity similar to those produced by pRscS+ wild-type cells (Fig. 7B and D). The sypC, sypD, and sypO mutants similarly produced Syp-polysaccharides that were indistinguishable from those of pRscS+ wild-type cells (Fig. 7C and D); these results may suggest a role for these proteins late in the assembly/export pathway. Finally, only the 15-kDa molecules could be detected in the LPS fractions from sypL, sypM, and sypR mutants (in the “other” group), suggesting that the Syp-dependent polysaccharides produced by these deletion mutants are structurally different from those produced by pRscS+ wild-type cells (Fig. 7D). This assay thus provides a useful mechanism to begin to assess the function of the various structural Syp proteins. We discuss below our interpretations of these data in light of the other phenotypes and putative functions of these proteins.

Fig 7.

Syp-dependent polysaccharide production by rscS-overexpressing syp mutant strains. Syp-dependent polysaccharides in the LPS fraction of extracts from rscS-overexpressing wild-type and syp deletion mutant cells were detected by immunoblotting using biofilm-specific antibodies. (A) Wild-type vector control (Vector) or RscS-overexpressing (pRscS+) strain (A); (B) pRscS+ glycosyltransferase mutants; (C) pRscS+ export mutants; (D) pRscS+ “other” mutants. The gel image is from a representative experiment.

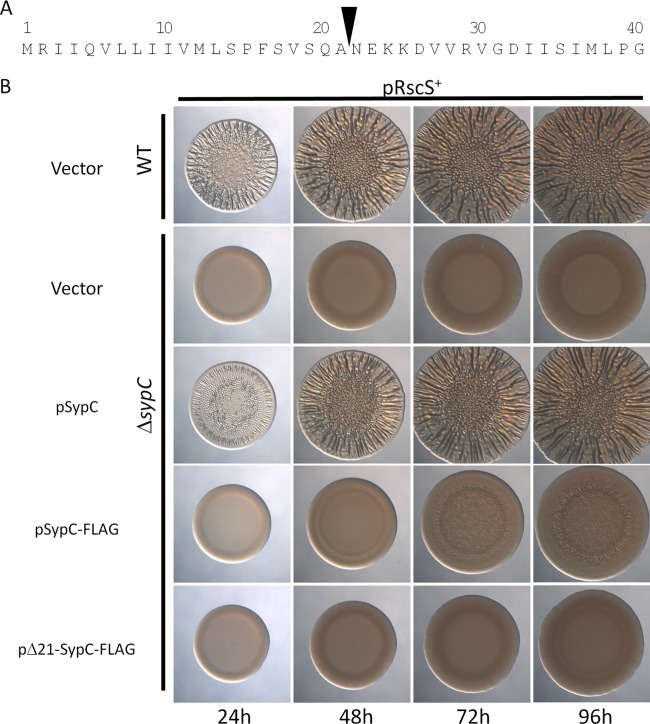

SypC function depends on both its N and C termini.

We chose to characterize the SypC protein further by investigating the importance of its N terminus. Using SignalP 4.0 (31), we found that the N terminus contains a putative signal sequence for export. This program predicts that SypC is cleaved after amino acid 21 (Ala) (Fig. 8A; see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). To test the importance of this sequence, we generated a derivative of sypC that lacks the predicted N-terminal signal sequence (obtained by fusing the ATG start codon to codon 22, which encodes the first amino acid in the predicted mature protein). To verify that this protein (Δ21-SypC) is expressed in V. fischeri cells, we also fused a FLAG epitope to the C-terminal end. Similarly, we generated a construct that expresses full-length SypC with a C-terminal FLAG fusion. Western blotting experiments confirmed the presence of both proteins in extracts from V. fischeri (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). We then asked whether these constructs permitted the formation of wrinkled colonies by the pRscS+ ΔsypC mutant. The N-terminal deletion mutant failed to complement: no wrinkling was observed, even after 4 days of incubation (Fig. 8B). These data suggest that the N terminus is important for SypC function. Surprisingly, however, the ability of FLAG-tagged full-length SypC to complement was also dramatically impaired: wrinkling began only after 48 h of incubation. Furthermore, even after 96 h, wrinkling by this strain remained substantially diminished relative to that by the untagged control, which, as described above (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), promoted full wrinkling within 48 h (Fig. 8B). These data suggested that either the specific tag (the FLAG epitope) or perturbations to the C terminus diminished the activity of SypC. To determine whether this effect was specific to the FLAG epitope, we generated an additional set of SypC constructs with an HA epitope tag fused at the C terminus. We found that the HA-tagged derivatives were produced (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) and behaved similarly to the FLAG-tagged versions: the development of wrinkled colonies by the pRscS+ ΔsypC strain expressing the SypC-HA protein was also both delayed and diminished relative to that of the untagged control, while the N-terminal deletion derivative failed to induce the development of wrinkled colonies (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Together, these data demonstrate that SypC function is substantially impacted by changes at both the N and C termini.

Fig 8.

Requirement for the N terminus of SypC for biofilm formation. (A) SignalP 4.0 (31) predicts a putative signal sequence in the N terminus of SypC. The first 40 amino acids of SypC are shown. The inverted triangle indicates the position of a predicted cleavage site after amino acid 21 (Ala). The N-terminal deletion mutant was generated by fusing the ATG start codon to codon 22. (B) Biofilm formation by the wild type or the ΔsypC mutant carrying rscS overexpression plasmid pARM7 and either the vector control (pVSV105) or a construct expressing a SypC derivative (untagged full-length protein [pSypC], FLAG epitope-tagged full-length protein [pSypC-FLAG], or FLAG epitope-tagged N-terminal deletion mutant [pΔ21-SypC-FLAG]). The specific SypC-expressing plasmids used were pSS25, pKV480, and pKV481.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we assessed the roles of the 14 structural proteins encoded within the syp locus of V. fischeri. Based on bioinformatic analyses, we grouped the proteins into three categories (glycosyltransferase, export, and other). Next, we generated nonpolar in-frame deletions and determined that the structural Syp proteins play a significant role in symbiotic colonization. They were also required for the full development of pRscS+-induced biofilm formation and, with two exceptions, matrix production. In all cases, severe biofilm defects in culture correlated with severe colonization defects; in two cases where relatively mild defects in biofilm formation were observed, there were also correspondingly mild defects in symbiotic colonization. These results support and extend previous work indicating a strong correlation between syp-dependent biofilm formation and colonization (21, 27, 49). However, the ability of the mutants to attach to glass was not predictive of colonization proficiency, suggesting that this phenotype, while induced by RscS, does not fully depend on syp. Finally, our recently described ability to evaluate Syp-polysaccharide production (36) permitted an important first-level assessment of the putative functions of these proteins in polysaccharide biosynthesis and export. These results are summarized in Table 2.

Characterizations of capsular and LPS biosynthesis pathways in various bacterial systems have revealed two major pathways for the export of polysaccharides across membranes: the ABC transporter-dependent pathway and the Wzy-dependent pathway (33, 45). The ABC transporter-dependent pathway employs Wzm/KpsM and Wzt/KpsT (the permease and ATP hydrolysis components of an ABC class 2 transporter, respectively) to drive polysaccharide transport across both inner and outer membranes in a one-step transport mechanism (33). None of the Syp proteins, however, exhibited similarity to ABC-type transporters. In contrast to this one-step pathway, the Wzy-dependent export pathway uses a two-step process to export polysaccharides across the two membranes: the O-antigen translocase/flippase Wzx transports GT-generated polysaccharide across the inner membrane, and the Wza protein transports it across the outer membrane (45). Additional proteins, such as Wzy itself (an O-antigen polymerase) and Wzz (a polysaccharide chain length regulator), function in the periplasm to modify the developing polysaccharide. Although none of the Syp proteins appear to be true orthologs of the Wzy pathway proteins, many contain domains that are similar to those present in members of the Wzy-dependent pathway or else are predicted to have analogous functions. For example, SypC contains a Wza domain, and SypO contains a Wzz domain. Similarly, SypK is predicted to be a flippase protein. Based on these and other bioinformatic analyses, we propose that the production and export of Syp-dependent polysaccharides depend on a pathway that is similar to the Wzy-dependent pathway. Since the proteins are not true orthologs, the details may be different. However, the Wzy-dependent pathway provides a reasonable framework for the development of hypotheses regarding the putative functions of the Syp proteins in polysaccharide biosynthesis and export. Specifically, we propose that GTs function in the cytoplasm or cytoplasmic membrane to generate a polysaccharide chain that is subsequently flipped to the periplasm by SypK and, after other modifications, is exported across the outer membrane via SypC. Below, we discuss our data with respect to this model of polysaccharide biosynthesis and export.

SypH, SypI, SypJ, SypN, SypP, and SypQ are predicted GT proteins. GTs are ubiquitous enzymes that sequentially catalyze the transfer of specific sugar moieties to target molecules (39). With one exception (sypI), the GT mutants exhibited severe defects in colonization and biofilm formation. The same biofilm-defective mutants also reacted negatively in the immunoblotting experiments, a severe defect which indicates that these proteins function at an early stage of polysaccharide biosynthesis (Fig. 7B). Finally, four of the GT mutants (sypH, sypJ, sypN, and sypP) exhibited a striking swollen-cell phenotype (Fig. 6B). It is possible that this phenotype results from the premature termination of Syp-polysaccharide biosynthesis, causing the intracellular accumulation of immature or partially degraded Syp-polysaccharide molecules. Alternatively, the production of aberrant molecules may exert intolerable stress on cells, resulting in the appearance of swollen morphology. A deeper understanding of the roles of these enzymes awaits the development of additional tools to investigate the production of polysaccharide intermediates and/or the enzymatic function of each protein. In contrast to the other GT mutants, the sypI mutant was only mildly defective for colonization and biofilm formation (Fig. 2 to 5). Why is this GT mutant not as defective as the others? Perhaps SypI functions late in the sequence of events leading to polysaccharide chain development, adding a structure, such as a branch, that is important but not critical for the observed phenotypes. Alternatively, perhaps a similar enzyme from this or another locus can substitute for SypI function.

The sypK mutant largely phenocopies the GT mutants, a result which suggests that SypK functions at or near the same step in polysaccharide biosynthesis. The sypK mutant was the only mutant, besides the GT mutants, for which no bands could be detected in our immunoblot analyses (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, the sypK mutant also exhibited the swollen-cell morphology (Fig. 6C), suggesting that it was accumulating immature or degraded polysaccharide molecules. SypK contains the RfbX domain, indicating that it may function as a polysaccharide flippase like the LPS flippase Wzx (RfbX). In S. enterica, a wzx mutant accumulated O-antigen in the cytoplasm (20). Like Wzx, SypK appears to contain numerous alpha-helical transmembrane (TM) regions (12 predicted by TMPred analysis of SypK [15]), indicating an integral membrane protein. We thus propose that SypK is an inner membrane protein responsible for “flipping” the developing polysaccharide chain across the inner membrane.

Finally, our model predicts that SypC functions to export the polysaccharide across the outer membrane. The sypC mutant exhibited severe defects in biofilm formation and matrix production (Fig. 3C, 4C, and 6C). However, it produced apparently wild-type polysaccharide species detectable by immunoblot experiments (Fig. 7C), suggesting that SypC functions at a late stage in the process. Support for our hypothesis comes from previous studies of Vibrio vulnificus, in which a mutation of the gene encoding Wza, a protein responsible for transport across the outer membrane, similarly did not abolish capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis: the polysaccharide was made but not exported (46). SypC contains an intact Wza domain (COG1596) as well as multiple regions with apparently incomplete Wza domains (51). However, SypC differs in size from other Wza proteins (full-length SypC is 703 amino acids in length, whereas Wza proteins from E. coli and Vibrio vulnificus are only 379 and 410 amino acids, respectively), suggesting that it may also carry out an additional function. Both the E. coli and V. fischeri proteins have or appear to have a signal peptide that would direct them across the inner membrane, but neither protein has the β-barrel structure typical of outer membrane proteins (1). We found that the putative signal sequence was important for SypC function, as the deletion of the N terminus abrogated the function of SypC. In addition, we found that perturbations of the C terminus also severely diminished the activity of SypC; perhaps the epitope tags which we introduced impacted protein assembly or proper localization. Unfortunately, the severely diminished function of the tagged protein precluded an investigation of the localization of SypC. To determine SypC's location, it will be necessary either to generate anti-SypC antibodies or identify a region of the protein that is permissive to the insertion of epitope sequences. A further understanding of SypC function will depend on the determination of its localization and structure, the cellular location of the Syp-dependent polysaccharides in the sypC mutant, and assays to confirm its putative outer membrane transport function.

We grouped the rest of the Syp proteins (SypB, SypD, SypL, SypM, SypO, and SypR) into the “other” category. Western blot analyses permitted us to further subdivide this group (Fig. 7D): three of the mutants (sypB, sypD, and sypO) were competent to produce all three molecules, suggesting a late-stage defect, whereas the other three mutants (sypL, sypM, and sypR) lacked the higher-molecular-weight species. Because the loss of SypB had little impact on biofilm formation or colonization, it is not surprising that it did not impact Syp-polysaccharide production either. The function of SypB is unknown, but its C-terminal domain contains the OmpA_C-like domain, which, in other proteins, such as E. coli OmpA (44), functions in peptidoglycan binding; its N terminus contains a stretch of amino acids that is hydrophobic and could serve as a secretion signal (31). Potentially, this protein localizes to the periplasm, where it makes polysaccharide assembly/export more efficient. In contrast to SypB, SypD and SypO, which have putative functions in chain length control, were critical for biofilm formation and colonization. We did not see any differences in the migrations of the molecular weight species from the wild type and these mutants when we extracted LPS, separated the molecules by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed them by immunoblotting (Fig. 7D). In E. coli K30, mutants defective for the chain length-regulatory gene wzc are able to produce K antigen-modified LPS (KLPS), which has a low molecular mass, but are unable to make detectable amounts of the K capsular polysaccharide, which has a high molecular mass (8, 47). Perhaps SypD and SypO contribute to the production of the large polysaccharide species previously detected under pRscS+ conditions by Yip et al. (49).

The last three “other” proteins (SypM, SypL, and SypR) all had apparent defects in the production of the 18- and 20-kDa polysaccharide species. SypM is predicted to be an acetyltransferase. If it indeed functions in this way, it may modify the polysaccharide such that it is recognized for assembly/export and/or by the biofilm-specific antibodies in our immunoblotting analyses. In support of the former hypothesis, the sypM mutant exhibited the swollen-cell phenotype, suggesting the accumulation of immature polysaccharide molecules. SypL is predicted to be a lipid A core–O-antigen ligase, which facilitates the transfer of O-antigen/polysaccharide onto a lipid carrier. Consistent with this putative function, SypL appears to be a membrane protein, with approximately 12 TM regions (15). Thus, the absence of SypL could result in incompletely assembled polysaccharide species. Finally, SypR is a putative undecaprenyl-phosphate galactose phosphotransferase. In other systems, similar proteins serve as a catalyst to initiate polysaccharide biosynthesis. In some bacteria, such as Caulobacter, there is redundancy in the initiation step of the process (40). Indeed, V. fischeri encodes two additional proteins that could serve a similar function. However, the possibility of redundancy, while potentially accounting for the detection of polysaccharide species observed by immunoblotting, does not explain the severe biofilm and colonization phenotypes of the sypR mutant.

In other systems, such as colonic acid biosynthesis in E. coli, the overproduction of the polysaccharide results in its incorporation into LPS molecules (26). From this work and our previous study (36), we propose that the bands detectable by immunoblotting represent a modified form of LPS. In particular, we found previously that SypK, the putative O-antigen flippase, is absolutely required for polysaccharide production/detection, and we showed here that SypL, the putative lipid A core–O-antigen ligase, is required for the higher-molecular-mass species. These results suggest that the 15-kDa molecule is the core structure and that the higher-molecular-mass molecules are the O-antigen part of LPS. We reported previously that the sypK mutant still made “normal” LPS molecules, as assessed by silver staining. These data indicated that the molecules that we can detect by immunoblotting may represent a special modified form of LPS. It is known that the O-antigen portion of LPS plays an important role in colonization by both pathogenic and symbiotic bacteria (18). Indeed, surface polysaccharides play an important role in V. fischeri for the interaction with and colonization of its host, E. scolopes (10). In particular, a recent study demonstrated that the O-antigen and core carbohydrate structures of normal LPS play a role in the early phases of V. fischeri colonization (32). However, our results for the sypD and sypO mutants, which displayed no apparent defect by immunoblotting but failed to promote biofilm formation and symbiosis, indicate that LPS is only one of the polysaccharide species necessary for biofilm formation. Further studies of these mutants will provide important insights into the role of the syp locus in colonization.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Linda Fox for her help with TEM experiments and Alan Wolfe and members of the Visick laboratory for their insightful experimental suggestions and critical reading of our manuscript.

This study was supported by NIH grant GM59690 to K.L.V.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 October 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Beis K, et al. 2004. Three-dimensional structure of Wza, the protein required for translocation of group 1 capsular polysaccharide across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 279:28227–28232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boettcher KJ, Ruby EG. 1990. Depressed light emission by symbiotic Vibrio fischeri of the sepiolid squid Euprymna scolopes. J. Bacteriol. 172:3701–3706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Branda SS, Vik S, Friedman L, Kolter R. 2005. Biofilms: the matrix revisited. Trends Microbiol. 13:20–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Costerton JW, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell DE, Korber DR, Lappin-Scott HM. 1995. Microbial biofilms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:711–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Darnell CL, Hussa EA, Visick KL. 2008. The putative hybrid sensor kinase SypF coordinates biofilm formation in Vibrio fischeri by acting upstream of two response regulators, SypG and VpsR. J. Bacteriol. 190:4941–4950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davis RW, Botstein D, Roth JR. 1980. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 7. DeLoney CR, Bartley TM, Visick KL. 2002. Role for phosphoglucomutase in Vibrio fischeri-Euprymna scolopes symbiosis. J. Bacteriol. 184:5121–5129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drummelsmith J, Whitfield C. 1999. Gene products required for surface expression of the capsular form of the group 1 K antigen in Escherichia coli (O9a:K30). Mol. Microbiol. 31:1321–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dunn AK, Millikan DS, Adin DM, Bose JL, Stabb EV. 2006. New rfp- and pES213-derived tools for analyzing symbiotic Vibrio fischeri reveal patterns of infection and lux expression in situ. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:802–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Foster JS, Apicella MA, McFall-Ngai MJ. 2000. Vibrio fischeri lipopolysaccharide induces developmental apoptosis, but not complete morphogenesis, of the Euprymna scolopes symbiotic light organ. Dev. Biol. 226:242–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Geszvain K, Visick KL. 2008. The hybrid sensor kinase RscS integrates positive and negative signals to modulate biofilm formation in Vibrio fischeri. J. Bacteriol. 190:4437–4446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Graf J, Dunlap PV, Ruby EG. 1994. Effect of transposon-induced motility mutations on colonization of the host light organ by Vibrio fischeri. J. Bacteriol. 176:6986–6991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis KN. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6557–6567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. 1989. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77:51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hofmann K, Stoffel W. 1993. TMbase—a database of membrane spanning proteins segments. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 374:166 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hussa EA, Darnell CL, Visick KL. 2008. RscS functions upstream of SypG to control the syp locus and biofilm formation in Vibrio fischeri. J. Bacteriol. 190:4576–4583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jacques M. 1996. Role of lipo-oligosaccharides and lipopolysaccharides in bacterial adherence. Trends Microbiol. 4:408–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lerouge I, Vanderleyden J. 2002. O-antigen structural variation: mechanisms and possible roles in animal/plant-microbe interactions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26:17–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Le Roux F, Binesse J, Saulnier D, Mazel D. 2007. Construction of a Vibrio splendidus mutant lacking the metalloprotease gene vsm by use of a novel counterselectable suicide vector. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:777–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu D, Cole RA, Reeves PR. 1996. An O-antigen processing function for Wzx (RfbX): a promising candidate for O-unit flippase. J. Bacteriol. 178:2102–2107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mandel MJ, Wollenberg MS, Stabb EV, Visick KL, Ruby EG. 2009. A single regulatory gene is sufficient to alter bacterial host range. Nature 458:215–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marchler-Bauer A, et al. 2009. CDD: specific functional annotation with the Conserved Domain Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D205–D210 doi:10.1093/nar/gkn845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marchler-Bauer A, Bryant SH. 2004. CD-Search: protein domain annotations on the fly. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:W327–W331 doi:10.1093/nar/gkh454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marchler-Bauer A, et al. 2011. CDD: a conserved domain database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:D225–D229 doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McGrath BC, Osborn MJ. 1991. Localization of the terminal steps of O-antigen synthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 173:649–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meredith TC, et al. 2007. Modification of lipopolysaccharide with colanic acid (M-antigen) repeats in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 282:7790–7798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morris AR, Darnell CL, Visick KL. 2011. Inactivation of a novel response regulator is necessary for biofilm formation and host colonization by Vibrio fischeri. Mol. Microbiol. 82:114–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morris AR, Visick KL. 2010. Control of biofilm formation and colonization in Vibrio fischeri: a role for partner switching? Environ. Microbiol. 12:2051–2059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moxon ER, Kroll JS. 1990. The role of bacterial polysaccharide capsules as virulence factors. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 150:65–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nyholm SV, McFall-Ngai MJ. 2004. The winnowing: establishing the squid-Vibrio symbiosis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:632–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. 2011. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods 8:785–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Post DM, et al. 2012. O-antigen and core carbohydrate of Vibrio fischeri lipopolysaccharide: composition and analysis of their role in Euprymna scolopes light organ colonization. J. Biol. Chem. 287:8515–8530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Raetz CR, Whitfield C. 2002. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71:635–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roberts IS. 1996. The biochemistry and genetics of capsular polysaccharide production in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:285–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ruby EG, Nealson KH. 1977. A luminous bacterium that emits yellow light. Science 196:432–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shibata S, Visick KL. 2012. Sensor kinase RscS induces the production of antigenically distinct outer membrane vesicles that depend on the symbiosis polysaccharide locus in Vibrio fischeri. J. Bacteriol. 194:185–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sonnenburg JL, Angenent LT, Gordon JI. 2004. Getting a grip on things: how do communities of bacterial symbionts become established in our intestine? Nat. Immunol. 5:569–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stabb EV, Ruby EG. 2002. RP4-based plasmids for conjugation between Escherichia coli and members of the Vibrionaceae. Methods Enzymol. 358:413–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Szymanski CM, et al. 2003. Detection of conserved N-linked glycans and phase-variable lipooligosaccharides and capsules from campylobacter cells by mass spectrometry and high resolution magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 278:24509–24520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Toh E, Kurtz HD, Jr, Brun YV. 2008. Characterization of the Caulobacter crescentus holdfast polysaccharide biosynthesis pathway reveals significant redundancy in the initiating glycosyltransferase and polymerase steps. J. Bacteriol. 190:7219–7231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Visick KL. 2009. An intricate network of regulators controls biofilm formation and colonization by Vibrio fischeri. Mol. Microbiol. 74:782–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Visick KL, Skoufos LM. 2001. Two-component sensor required for normal symbiotic colonization of Euprymna scolopes by Vibrio fischeri. J. Bacteriol. 183:835–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang L, Liu D, Reeves PR. 1996. C-terminal half of Salmonella enterica WbaP (RfbP) is the galactosyl-1-phosphate transferase domain catalyzing the first step of O-antigen synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 178:2598–2604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang Y. 2002. The function of OmpA in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 292:396–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Whitfield C. 2006. Biosynthesis and assembly of capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75:39–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wright AC, Powell JL, Kaper JB, Morris JG., Jr 2001. Identification of a group 1-like capsular polysaccharide operon for Vibrio vulnificus. Infect. Immun. 69:6893–6901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wugeditsch T, et al. 2001. Phosphorylation of Wzc, a tyrosine autokinase, is essential for assembly of group 1 capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 276:2361–2371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yildiz FH, Visick KL. 2009. Vibrio biofilms: so much the same yet so different. Trends Microbiol. 17:109–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yip ES, Geszvain K, DeLoney-Marino CR, Visick KL. 2006. The symbiosis regulator rscS controls the syp gene locus, biofilm formation and symbiotic aggregation by Vibrio fischeri. Mol. Microbiol. 62:1586–1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yip ES, Grublesky BT, Hussa EA, Visick KL. 2005. A novel, conserved cluster of genes promotes symbiotic colonization and σ54-dependent biofilm formation by Vibrio fischeri. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1485–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yoshida T, et al. 2003. Genes involved in the synthesis of the exopolysaccharide methanolan by the obligate methylotroph Methylobacillus sp strain 12S. Microbiology 149:431–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]