Abstract

Medication errors may result in serious safety issues for patients. Medication error issues are more prevalent among elderly patients, who take more medications and have prescriptions that change frequently. The challenge of obtaining accurate medication histories for the elderly at the time of hospital admission creates the potential for medication errors starting at admission.

A study at a central Texas hospital was conducted to assess whether an electronic medication checklist can enhance the accuracy of medication histories for the elderly. The empirical outcome demonstrated that medication errors were significantly reduced by using an electronic medication checklist at the time of admission. The findings of this study suggest that implementing electronic health record systems with decision support for identifying inaccurate doses and frequencies of prescribed medicines will increase the accuracy of patients’ medication histories.

Keywords: electronic medication checklist, medication history, adverse drug events (ADEs), admission interview, the elderly, medication errors, electronic health record

Introduction

The occurrence of medication errors in healthcare facilities in the United States is a widely noted problem, and prevention of medication errors has become a critically important national priority.1 In the medical field, an error is defined as “the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended (i.e., error of execution), or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim (i.e., error of planning).”2 In previous studies, several types of medication errors were identified, including commission errors (addition of a drug not used before admission), omission errors (deletion of a drug used before admission), and incorrect drug dose and/or frequency.3 Medication errors are associated with adverse drug events (ADEs) and with increased risk of patient morbidity and mortality.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 However; obtaining accurate medication histories can often be a difficult task for health professionals.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 The medication history in the hospital medical record is often incomplete, as 25 percent of the prescription drugs in use are not recorded and 61 percent of all patients have one or more drugs not registered.20 The Institute of Medicine report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System identified medication errors as the most common type of error in healthcare; medication errors occur commonly in hospitals and account for 1 out of 854 inpatient deaths.21

To avoid medication errors and ADEs, the Joint Commission mandated that all facilities accredited by it must “accurately and completely reconcile medications across the continuum of care.”22 The medication reconciliation process involves compiling a complete and accurate list of a patient's home medications and comparing that list to a provider's admission orders.23

The US Department of Health and Human Services Administration on Aging reported there were 36.3 million people 65 years of age or older in the United States in 2005.24 Prescription drugs were used more frequently by the elderly than by younger people, and the highest overall prevalence of medication use was among adults age 65 years and older: more than 40 percent of ambulatory patients over 65 years old use at least 5 medications per week, and 12 percent use at least 10 medications per week.25, 26 With the increased number of medications being taken, the possibility of an error is increased. The elderly use the most medications, change medication prescriptions frequently, and have the highest potential risk from errors in prescribing.27, 28, 29 Previous studies have estimated the prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly as ranging from 12 percent to 40 percent, and there was no decline in utilization of potentially inappropriate medications from 1995 to 2000.30 Incorrect use of medications in the elderly can increase the risks of falling, confusion, depression, constipation, immobility, and hip fractures.31, 32 Other potential problems are inappropriate drug interactions plus the condition that the prescription drug is not effective in treating.33

Researchers have identified multiple factors contributing to medication errors, including polypharmacy (defined as concurrent use of nine or more medications),34 the loss of the community pharmacy filter,35 language and cultural barriers,36 old age,37, 38 low health literacy,39, 40 multiple changes in medication regimens,41 and recall bias.42 These multiple factors lead to difficulties for patients, especially the elderly, in identifying their medication regimens upon admission. Dobrzanski et al.43 have identified that up to 27 percent of all hospital prescribing errors can be attributed to incomplete medication histories at the time of admission. Early identification and correction of admission medication errors may mitigate or prevent harm. In particular, the medication history is mainly based on the patient's self-reported medication history at the time of hospital admission. Inaccuracies in a medication history are not uncommon and are often caused by a patient's unreliable memory, hasty interviews, recording errors, or an interviewer's unfamiliarity with certain drugs.44, 45 Therefore, it is imperative that admission medication histories of the elderly be evaluated for accuracy.46

The literature suggests a lack of a gold standard47, 48 that constitutes a “good medication history.” Most research does not include a formal definition of a good medication history. Gleason et al.49 expressed that healthcare professionals need to educate patients concerning the importance of providing up-to-date medication lists and updating the information at every healthcare visit. A summary of safe-practice recommendations for reconciling medications at admission was published in the Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety in January 2006. The recommendations included collecting a complete and accurate list of current medications for each patient upon admission. The goal is to develop the most complete medication list possible, although it was noted that this may not always be possible. The second recommendation is to confirm the medication list with the patient and then assign principal responsibility for collecting the list to someone with sufficient expertise, within a context of shared accountability.50 In light of these broad and varied recommendations, it is clear that more specific interventions to obtain an accurate medication list are needed.

Beers et al.51 stated that the methods used for sharing information about medications were inadequate and increased the risk for medication errors. They proposed that focusing on standardized processes to gather medication information and using appropriate tools may enable nurses to obtain complete and accurate medication lists from the elderly. Developing nursing interventions to be used at the time of admission that assist the elderly in managing their medications can help prevent medication errors and patient death. Electronic health record (EHR) systems have the potential to reduce errors and improve quality of care.52, 53 As one of the applications in an EHR system, an electronic medication checklist is assumed to be able to reduce medication errors by using structured data input and an alert function. However, the alert function in an electronic medication checklist can also be a cause of medication errors because sometimes the alert function is turned off.54 In that case, a feature that was meant to help can be a problem in the end because people assume that safety measures are in place.

The purpose of this study is to assess whether an electronic medication checklist can enhance medication histories of the elderly obtained at the time of hospital admission. In this study, the researchers proposed the following research question: Will an electronic medication checklist enhance the accuracy of medication histories obtained at the time of hospital admission for elderly individuals, 65 years of age and older, who are taking five or more prescribed medications?

Methods

This study was conducted at a central Texas hospital in fall 2011. The hospital is a 400-bed facility located in a suburban community. The hospital had been using a handwritten process to account for medication histories upon admission. The study was conducted partially because the hospital transitioned from one EHR system to a new EHR system within two months of the time of the study. The hospital wanted to assess the electronic medication checklist, which was a new application to be included in the new EHR system.

To conduct the research, convenience samples of eligible professional registered nurses were recruited first. Since the study was conducted without controlling for staffing levels, the researchers wanted to ensure that the participating nurses had sufficient and similar capabilities. Thus, participants’ inclusion criteria included current employment of at least a 0.5 full-time equivalent (FTE), or 20 hours per week. Registered nurses working less than 0.5 FTE, float/PRN staff (any staff not regularly working on the specified unit), and any staff floated to the unit were excluded from the study. Eight registered nurses who satisfied the criteria were recruited. Nurse managers at the hospital were asked to explain the study to the nursing staff, and then a three-hour training on the use of the new electronic medication checklist was provided by the vendor to the participating nurses.

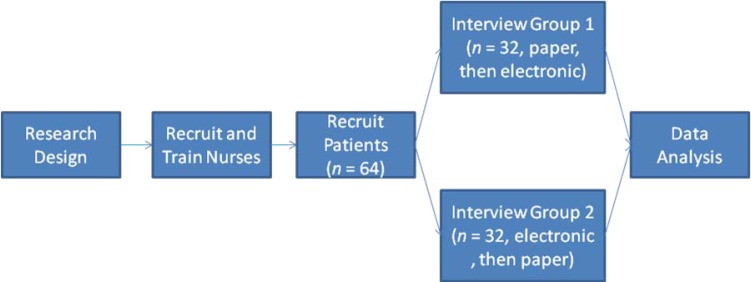

Next, research patients were recruited in the hospital on a voluntary basis. To eliminate patient-related factors that could influence medication errors, such as language,55 the patients selected for the study included 64 inpatients, including both males and females, with at least one week of hospitalization in this hospital, who were 65 years of age or older, taking five or more medications, alert and oriented, and English speaking. The 64 patients’ medication histories during the hospitalization were recorded in the hospital's new EHR system (under the pilot stage) as the assessment baseline. Within three days before discharge, mock admission interviews were conducted with the participating patients. The nurses interviewed the patients and documented the patient's accounting of the medications taken during this hospitalization, using both handwritten documentation and an electronic medication checklist. Each nurse interviewed eight patients and documented 16 medication histories, recording both a handwritten document and the electronic checklist for each patient. To eliminate the external validity risk of repeated tests, half of the patients were interviewed by using handwritten documentation first, then using an electronic medication checklist two days later; the other half were interviewed with an electronic medication checklist first, then using handwritten documentation two days later. The sample size of 32 patients per group was based on Cohen's56 recommended size of 28. The experimental sample size was increased by 15 percent to allow for missing data; thus the final sample size was 32 patients for each group. Medication histories were collected from the 64 patients. This was a cross-sectional, repeated-measures study. The data collection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Data Collection Process

After the interviews, medication reconciliations were conducted by comparing both the paper-based and electronically assisted documentation with the patients’ medication records in the hospital's existing EHR system. Medication errors were identified if the medication had an incorrect dose or frequency. One point was assigned for each error. Also, any additional medications added to the medication list (commissions) or medications missing from the list (omissions) were assigned two points. Omissions and commissions were scored with two points due to an added or missing medication being significant enough to have a higher allocation of weight. In fact, some studies of medication errors only counted commissions and omissions.57, 58 The total number of points assigned was the medication error score for each patient interview. The medication errors found in the study are reported by categories in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data Summary

| Number of Errors by Categories |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Error | Frequency Error | Dose Error | Commission Error | Omission Error | ||

| Group 1, n = 32 (paper, then electronic) | Paper-based documentation | 9 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 5 |

| Electronic checklist | 20 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 | |

| Group 2, n = 32 (electronic, then paper) | Electronic checklist | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Paper-based documentation | 26 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

Results

In this study, both parametric and nonparametric tests were applied. The parametric test in Table 2 shows that in Group 1 (paper-based interview first, then electronic), the mean medication error scores are 1 when using paper-based documentation and 0.4063 when using the electronic medication checklist, while in Group 2 (electronic checklist first, then paper-based interview), the mean medication error scores are 0 when using the electronic medication checklist and 0.1875 when using paper-based documentation. A comparison of the two means within the same groups, ZGroup 1 = 2.6747, p < .01, and ZGroup 2 = −3.3205, p < .001, illustrates that in both groups, the medication error scores obtained using the electronic medication checklist are significantly lower than those obtained using paper-based documentation.

Table 2.

Parametric Test Outcomes and Comparison

| Error Scores |

Comparison |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum | Mean | SD | Z | p-value | r | ||

| Group 1, n = 32 (paper, then electronic) | Paper-based documentation | 32 | 1 | 0.8424 | 2.6747 | 0.0075 | 0.43 |

| Electronic checklist | 13 | 0.4063 | 0.5599 | ||||

| Group 2, n = 32 (electronic, then paper) | Electronic checklist | 0 | 0 | 0 | −3.3205 | 0.0009 | −0.51 |

| Paper-based documentation | 6 | 0.1875 | 0.3966 | ||||

The above tests rely on an assumption of normal distribution. However, the data sets in this study are not normally distributed according to the tests of normality (Tables 3 and 4), since the Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests are significant (p = .000). Therefore, the researchers applied nonparametric tests to retest the data sets. Because the results in this study came from repeated measures, the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, which are used in comparing two related conditions,59 were adopted. The analysis was run with SPSS v. 18. The outcomes of the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests are reported in Tables 5 and 6. In these two tables, note that in both groups, the median of differences between using an electronic checklist and using a paper chart are significantly different, ZGroup 1 = 2.449, p < .05 and ZGroup 2 = −3.945, p = .000.

Table 3.

Tests of Normality in Group 1

| Kolmogorov-Smirnova |

Shapiro-Wilk |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Statistic | df | Sig. | |

| Electronic | .391 | 32 | .000 | .672 | 32 | .000 |

| Paper | .281 | 32 | .000 | .836 | 32 | .000 |

Lilliefors significance correction

Table 4.

Tests of Normality in Group 2

| Kolmogorov-Smirnova |

Shapiro-Wilk |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Statistic | df | Sig. | |

| Paper | .494 | 32 | .000 | .478 | 32 | .000 |

Note: Electronic result is constant and was omitted from the test.

Lilliefors significance correction

Table 5.

Nonparametric Test Statistics

| Differences between Using a Paper Chart and Using an Electronic Checklist in Group 1 | Differences between Using an Electronic Checklist and Using a Paper Chart in Group 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized test statistics (Z) | 2.449 | −3.945 |

| Asymp. sig. (two-tailed) | .014 | .000 |

| Effect size (r) | 0.31 | −0.49 |

Table 6.

Nonparametric Hypothesis Test Summary

| Null Hypothesis | Test | Sig. | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The median of differences between using an electronic checklist and using a paper chart equals 0 in Group 1. | Related samples Wilcoxon signed-rank test | .000 | Reject the null hypothesis |

| 2 | The median of differences between using an electronic checklist and using a paper chart equals 0 in Group 2. | Related samples Wilcoxon signed-rank test | .014 | Reject the null hypothesis |

In this study, both the parametric and nonparametric tests demonstrate that the electronic medication checklist results in a lower medication error rate than when the medication history is documented by handwritten transcription at the time of admission. These findings are similar to previous studies,60, 61, 62 which identified that using a standardized reconciliation process decreased medication errors. Reasons for the discrepancies include the fact that EHR systems have all medications names listed, so the possibility of error due to free typing in the medication field is eliminated. And when the alert functions are appropriately used in the EHR system, the medication alert function also reduces dose and frequency errors.

This research demonstrates that with a diligent approach to the way in which nurses obtain medication histories, improvement in outcomes may be delivered through the reduction of medication errors. An electronic medication checklist can decrease medication transcription errors when it is used by professional nurses at the time of hospital admission. The results of this study and other studies discussed above suggest that implementation of EHR systems with decision support for identifying inaccurate medication doses and frequencies is expected to increase the accuracy of patients’ medication histories.

Limitations

First, the most obvious limitation to this study is the lack of a gold standard to identify what constitutes a good medication history. Second, nurses participating in the study were primarily on the first shift because this timing made it easier for the researchers to compile the documentation after the mock interviews. The nurses on the first shift may have greater mastery of the new electronic medication checklist than the nurses on other shifts because the vendor representatives are available during that time. In future research, the nurses on other shifts should be included. Third, this study was conducted over a limited time span. When the hospital was approached about this study, the hospital was planning to implement a new EHR system within six weeks. Therefore, the window of opportunity for this study was small. Variables such as staffing levels and patient perception were not studied or controlled. Finally, the sample for this study was from one central Texas hospital, which limits the generalization of results.

Contributor Information

Tiankai Wang, Tiankai Wang, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Health Information Management Department at Texas State University–San Marcos in San Marcos, TX..

Sue Biederman, Sue Biedermann, MSHP, RHIA, FAHIMA, is a department chair and associate professor in the Health Information Management Department of Texas State University–San Marcos in San Marcos, TX..

Notes

- 1.Aspden P., editor; Wolcott J., editor; Bootman J. L., editor; Cronenwett L. R., editor. Preventing Medication Errors: Quality Chasm Series. Washington: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Patient Safety: Achieving a New Standard for Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. p. 30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tam V. Knowles S. Cornish P. Fine N. Marchesano R. Etchells E. Frequency, Type and Clinical Importance of Medication History Errors at Admission to Hospital: A Systematic Review. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2005;173(5):510–15. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.045311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker K. N. Flynn E. A. Pepper G. A., et al. Medication Errors Observed in 36 Health Care Facilities. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162:1897–1903. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bobb A. Gleason K. Husch M., et al. The Epidemiology of Prescribing Errors: The Potential Impact of Computerized Prescribing Order Entry. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164:785–92. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.7.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lau H. Florax C. Porsius A. De Boer A. The Completeness of Medication Histories in Hospital Medical Records of Patients Admitted to General Internal Medicine Wards. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2005;49:597–603. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Doormaal J. E. van den Bemt P. M. Mol P. G., et al. Medication Errors: The Impact of Prescribing and Transcribing Errors on Preventable Harm in Hospitalised Patients. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2009;18:22–27. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.023812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lizer M. Brackbill M. Medication History Reconciliation by Pharmacists in an Inpatient Behavioral Health Unit. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2007;64:1087–91. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aspden, P., J. Wolcott, J. L. Bootman, and L. R. Cronenwett (Editors). Preventing Medication Errors: Quality Chasm Series

- 10.Tam, V., S. Knowles, P. Cornish, N. Fine, R. Marchesano, and E. Etchells. “Frequency, Type and Clinical Importance of Medication History Errors at Admission to Hospital: A Systematic Review.” [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Lau, H., C. Florax, A. Porsius, and A. De Boer. “The Completeness of Medication Histories in Hospital Medical Records of Patients Admitted to General Internal Medicine Wards.” [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Vira T. Colquhoun M. Etchells E. Reconcilable Differences: Correcting Medication Errors at Hospital Admission and Discharge. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2006;15:122–26. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornish P. Knowles S. Marchesano R. Tam V. Shadowitz S. Juurlink D. Etchells E. Unintended Medication Discrepancies at the Time of Hospital Admission. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165:424–29. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.4.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gleason K. M. Groszek J. M. Sullivan C. Rooney D. Barnard C. Noskin G. A. Reconciliation of Discrepancies in Medication Histories and Admission Orders of Newly Hospitalized Patients. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2004;61:1689–95. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.16.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaboli P. J. McClimon B. J. Hoth A. B. Barnett M. J. Assessing the Accuracy of Computerized Medication Histories. American Journal of Managed Care. 2004;10(2):872–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bedell S. Jabbour S. Goldberg R. Glaser H. Gobble S. Young-Xu Y. Graboys T. Ravid S. Discrepancies in the Use of Medications. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160:2129–34. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beers M. Munekata M. Storrie M. The Accuracy of Medication Histories in the Hospital Medical Records of Elderly Persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1990;38(11):1183–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leister K. A. Edwards W. A. Christensen D. B. Clarke H. A Comparison of Patient Drug Regimens as Viewed by the Physician, Pharmacist and Patient. Medical Care. 1981;19:658–64. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198106000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Web M&M: Morbidity and Mortality Rounds on the Web. Case and Commentary: “Electronic Err.” Available at http://webmm.ahrq.gov/case.aspx?caseID=79&searchStr=electronic+medication+lists (accessed March 17, 2012).

- 20.Lau, H., C. Florax, A. Porsius, and A. De Boer. “The Completeness of Medication Histories in Hospital Medical Records of Patients Admitted to General Internal Medicine Wards.” [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Institute of Medicine. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joint Commission. Hospitals’ National Patient Safety Goals. Available at http://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/npsgs.aspx (accessed March 17, 2012).

- 23.Agrawal A. Wu W. Khachewatsky I. Evaluation of an Electronic Medication Reconciliation System in Inpatient Setting in an Acute Care Hospital. In: Kuhn K., et al., editors. MEDINFO 2007: Proceedings of the 12th World Congress on Health (Medical) Informatics. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2007. pp. 1027–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Department of Health and Human Services Administration on Aging. A Profile of Older Americans: 2005. Available at http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/general/profile_2005.pdf (accessed February 10, 2012).

- 25.Fu A. Z. Liu G. G. Christensen D. B. Inappropriate Medication Use and Health Outcomes in the Elderly. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:1934–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufman D. Kelly J. Rosenberg L. Anderson T. Mitchell A. Recent Patterns of Medication Use in the Ambulatory Adult Population of the United States: The Sloane Survey. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287(3):337–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beers, M., M. Munekata, and M. Storrie. “The Accuracy of Medication Histories in the Hospital Medical Records of Elderly Persons.” [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Pham C. Dickman R. Minimizing Adverse Drug Events in Older Patients. American Family Physician. 2007;76(12):1837–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorman Marek K. Antle L. Medication Management of the Community-Dwelling Older Adult. In: Hughes R., editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simon S. R. Chan K. A. Soumerai S. B., et al. Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use by Elderly Persons in U.S. Health Maintenance Organizations, 2000-2001. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:227–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanlon J. Schmader K. Kornkowski M. Adverse Drug Events in High Risk Older Outpatients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1997;45:945–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crotty M. Rowett D. Spurling L. Giles L. Phillips P. Does the Addition of a Pharmacist Transition Coordinator Improve Evidence-based Medication Management and Health Outcomes in Older Adults Moving from the Hospital to a Long-Term Care Facility? Results of a Randomized, Controlled Trial. American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacology. 2004;2(4):257–64. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhan C. Sangl J. Bierman A. S. Miler M. R. Friedman B. Wickizer S. W. Meyer G. S. Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in the Community-Dwelling Elderly: Findings from the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. JAMA. 2001;286(22):2823–29. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.22.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bedell, S., S. Jabbour, R. Goldberg, H. Glaser, S. Gobble, Y. Young-Xu, T. Graboys, and S. Ravid. “Discrepancies in the Use of Medications.” [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Scharz A. Faber U. Borner K. Keller F. Offermann G. Molzahn M. Reliability of Drug History in Analgesic Users. Lancet. 1984;2:1163–64. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91608-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gleason K. McDaniel M. Feinglass J. Baker D. Lindquist L. Liss D. Nosin G. Results of the Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) Study: An Analysis of Medication Reconciliation Errors and Risk Factors at Hospital Admission. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(5):441–47. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1256-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bedell, S., S. Jabbour, R. Goldberg, H. Glaser, S. Gobble, Y. Young-Xu, T. Graboys, and S. Ravid. “Discrepancies in the Use of Medications.” [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.“U.S. Pharmacopeia 8th Annual MEDMARX-Report Indicates Look-Alike/Sound-Alike Drugs Lead to Thousands of Medication Errors Nationwide.” Press release. Available at http://www.reuters.com/article/2008/01/29/idUS210935+29-Jan-2008+PRN20080129 (accessed March 15, 2012).

- 39.Berkman N. D. DeWalt D. A. Pignone M. P., et al. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 87. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; July 16, 2009. Literacy and Health Outcomes (AHRQ Publication No. 04-E007-2, prepared by RTI International-University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0016) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baker D. W. Gazmararian J. A. Williams M. V., et al. Functional Health Literacy and the Risk of Hospital Admission among Medicare Managed Care Enrollees. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1278–83. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bates D. W. Spell N. Cullen D. J. Budick E. Laird N. Peterson L., et al. The Cost of Adverse Drug Events in Hospitalized Patients: Adverse Drug Events Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1997;277(4):307–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lau, H., C. Florax, A. Porsius, and A. De Boer. “The Completeness of Medication Histories in Hospital Medical Records of Patients Admitted to General Internal Medicine Wards.” [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Dobrzanski S. Hammond I. Khan G. Holdsworth H. The Nature of Hospital Prescribing Errors. British Journal of Clinical Governance. 2002;7:187–93. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scharz, A., U. Faber, K. Borner, F. Keller, G. Offermann, and M. Molzahn. “Reliability of Drug History in Analgesic Users.” [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Jacobson J. Ensuring Continuity of Care and Accuracy of Patients’ Medication History on Hospital Admission. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2002;59:1054–55. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/59.11.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gleason, K., M. McDaniel, J. Feinglass, D. Baker, L. Lindquist, D. Liss, and G. Nosin. “Results of the Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) Study: An Analysis of Medication Reconciliation Errors and Risk Factors at Hospital Admission.” [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Tam, V., S. Knowles, P. Cornish, N. Fine, R. Marchesano, and E. Etchells. “Frequency, Type and Clinical Importance of Medication History Errors at Admission to Hospital: A Systematic Review.” [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Cornish, P., S. Knowles, R. Marchesano, V. Tam, S. Shadowitz, D. Juurlink, and E. Etchells. “Unintended Medication Discrepancies at the Time of Hospital Admission.” [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Gleason, K. M., J. M. Groszek, C. Sullivan, D. Rooney, C. Barnard, and G. A. Noskin. “Reconciliation of Discrepancies in Medication Histories and Admission Orders of Newly Hospitalized Patients.” [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Rogers G. Alper E. Brunelle D. Federico F. Fenn C. Leape L. Kirle L. Ridley N. Clarridge B. Bolcic-Jankovic D. Griswold R. Hanna E. Annas C. National Patient Safety Goals: Reconciling Medications at Admission: Safe Practice Recommendations and Implementation Strategies. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2006;32(1):37–50. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beers, M., M. Munekata, and M. Storrie. “The Accuracy of Medication Histories in the Hospital Medical Records of Elderly Persons.” [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy; Booz Allen Hamilton. Evaluation Design of the Business Case of Health Information Technology in Long-Term Care: Final Report. 2006. Available at http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2006/BCfinal.pdf

- 53.Walker J. Carayon P. Leveson N. Paulus R. Tooker J. Chen H. Bothe A. Stewart W. EHR Safety: The Way Forward to Safe and Effective Systems. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2008;15:272–77. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Sijs H. Aarts J. Vulto A. Berg M. Overriding of Drug Safety Alerts in Computerized Physician Order Entry. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2006;13(2):138–47. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gleason, K., M. McDaniel, J. Feinglass, D. Baker, L. Lindquist, D. Liss, and G. Nosin. “Results of the Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) Study: An Analysis of Medication Reconciliation Errors and Risk Factors at Hospital Admission.” [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Cohen J. Quantitative Methods in Psychology. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):155–59. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lau, H., C. Florax, A. Porsius, and A. De Boer. “The Completeness of Medication Histories in Hospital Medical Records of Patients Admitted to General Internal Medicine Wards.” [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Beers, M., M. Munekata, and M. Storrie. “The Accuracy of Medication Histories in the Hospital Medical Records of Elderly Persons.” [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Field A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gleason, K. M., J. M. Groszek, C. Sullivan, D. Rooney, C. Barnard, and G. A. Noskin. “Reconciliation of Discrepancies in Medication Histories and Admission Orders of Newly Hospitalized Patients.” [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Zhan, C., J. Sangl, A. S. Bierman, M. R. Miler, B. Friedman, S. W. Wickizer, and G. S. Meyer. “Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in the Community-Dwelling Elderly: Findings from the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.” [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Pronovost P. Weast B. Schwartz M. Wyskiel R. Prow D. Milanovich S. Berenholtz S. Dorman T. Lipsett P. Medication Reconciliation: A Practical Toll to Reduce the Risk of Medication Errors. Journal of Critical Care. 2003;18(4):201–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]