Abstract

Activation of anion channels by blue light begins within seconds of irradiation in seedlings and is related to the ensuing growth inhibition. 5-Nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)-benzoic acid (NPPB) is a potent, selective, and reversible blocker of these anion channels in Arabidopsis thaliana. Here we show that 20 μm NPPB blocked 72% of the blue-light-induced accumulation of anthocyanin pigments in seedlings. Feeding biosynthetic intermediates to wild-type and tt5 seedlings provided evidence that NPPB prevented blue light from up-regulating one or more steps between and including phenylalanine ammonia lyase and chalcone isomerase. NPPB was found to have no significant effect on the blue-light-induced increase in transcript levels of PAL1, CHS, CHI, or DFR, which are genes that encode anthocyanin-biosynthetic enzymes. Immunoblots revealed that NPPB also did not inhibit the accumulation of the chalcone synthase, chalcone isomerase, or flavanone-3-hydroxylase proteins. This is in contrast to the reduced anthocyanin accumulation displayed by a mutant lacking the HY4 blue-light receptor, as hy4 displayed reduced expression of the above enzymes. Taken together, the data indicate that blue light acting through HY4 leads to an increase in the amount of biosynthetic enzymes, but blue light must also act through a separate, anion-channel-dependent system to create a fully functional biosynthetic pathway.

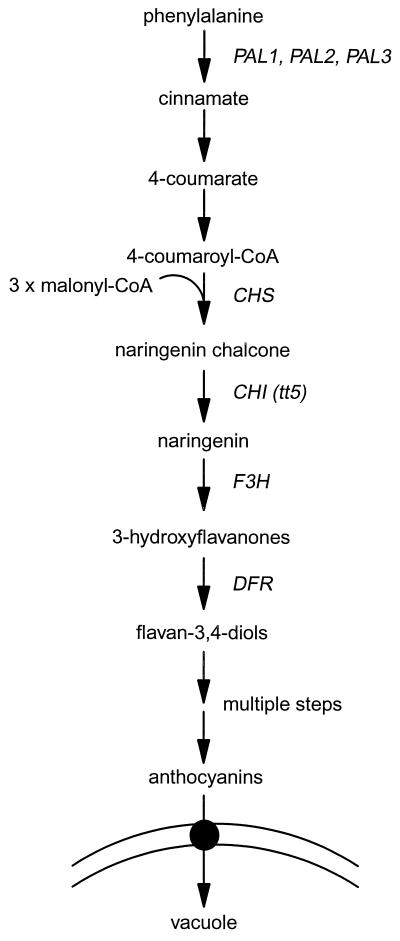

Anthocyanin pigments accumulate in response to light in the seedlings of many species. This accumulation is preceded by increased transcription of genes encoding enzymes in the anthocyanin-biosynthetic pathway, which is shown in Figure 1. A view that has emerged from various photobiological, biochemical, and genetic studies is that transcriptional control of the biosynthetic enzymes accounts for the effects of light on anthocyanin accumulation (Mol et al., 1996). Even when the inductive treatment is something other than light, such as a pathogen-related elicitor or a nutrient deficiency, transcriptional control of these genes has satisfactorily explained the resulting anthocyanin accumulation (Chappel and Hahlbrock, 1984; Dangl, 1991; Dixon and Pavia, 1995).

Figure 1.

The anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway. The chemical intermediates and the gene symbols for several of the cloned biosynthetic enzymes are shown.

In seedlings of species such as mustard and tomato, phytochrome is the important photoreceptor controlling the accumulation of anthocyanins (Lange et al., 1970; Batschauer et al., 1991; Frohnmeyer et al., 1992; Neuhaus et al., 1993). However, phytochrome is much less important to the accumulation of anthocyanins in Arabidopsis seedlings. Instead, one or more photoreceptors specific for blue light is largely responsible for the gene activation and pigment accumulation induced by visible wavelengths (Feinbaum et al., 1991; Kubasek et al., 1992; Batschauer et al., 1996). It is clear that the flavoprotein photoreceptor encoded by the HY4 gene (Ahmad and Cashmore, 1993) functions importantly in the response to blue light (Ahmad et al., 1995; Jackson and Jenkins, 1995). In parsley and Arabidopsis radiation in the UVA and UVB wavelength bands is also very effective (Bruns et al., 1986; Ohl et al., 1989; Kubasek et al., 1992; Christie and Jenkins, 1996), operating synergistically with blue light through separate receptors (Fuglevand et al., 1996).

In the case of phytochrome-mediated anthocyanin accumulation, information about how the photoreceptor is coupled to the increase in transcription is beginning to emerge: a role for cGMP has been supported by the results of microinjection studies performed with a phytochrome-deficient mutant of tomato (Neuhaus et al., 1993). As for the blue light and UV receptor(s) responsible for anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis, the effects of pharmacological agents indicated that an increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ is somehow involved in, although not sufficient to cause, the light-induced increase in CHS mRNA in suspension-cultured cells (Christie and Jenkins, 1996). Also, the effects of kinase and phosphatase inhibitors indicate a role for phosphorylation in the signal cascade (Christie and Jenkins, 1996). Unfortunately, the role proposed for Ca2+ does not agree with the recent finding that blue light does not induce detectable changes in cytoplasmic Ca2+ in aequorin-expressing Arabidopsis seedlings (Lewis et al., 1997). Perhaps the response mechanism of suspension-cultured cells differs from that of etiolated seedlings, or the requirement for Ca2+ is satisfied by small increases in its concentration that could not be detected by measuring aequorin luminescence.

The rapid inhibition of hypocotyl elongation in etiolated seedlings is a blue-light response that, until the present work, was not obviously related to anthocyanin accumulation. The growth inhibition begins after a lag time of approximately 30 s, depending on the fluence rate of blue light and the species used. Preceding the onset of rapid growth inhibition by a few seconds is the activation of anion channels at the plasma membrane of growing cells (Cho and Spalding, 1996). The channel activation increases the conductance of the membrane to anions such as Cl−, facilitating a passive flux of anions down their gradient in electrochemical potential, i.e. out of the cell. The electric current produced by this flux shifts the membrane potential to more positive values. Thus, a depolarization of the membrane quickly precedes the onset of growth inhibition induced by blue light (Spalding and Cosgrove, 1989).

An anion-channel blocker known as NPPB potently, selectively, and reversibly blocks the blue-light-activated anion channel of Arabidopsis, as well as the blue-light-induced membrane depolarization in intact seedlings (Cho and Spalding, 1996; Lewis et al., 1997). Consistent with this channel activation being a signal-transducing event, treatment of seedlings with NPPB renders hypocotyl growth less sensitive to blue light (Cho and Spalding, 1996). HY4 is not the photoreceptor mediating the rapid growth inhibition, as a normal response was observed in a null hy4 mutant (B.M. Parks and E.P. Spalding, unpublished observations).

Superimposed on the rapid inhibition of hypocotyl growth by blue light is an inhibition that begins after 8 h of blue light. Unlike the rapid response, this persistent long-term inhibition is mediated by the HY4 photoreceptor (B.M. Parks and E.P. Spalding, unpublished observations). The emerging picture is that two genetically separable, blue-light-specific photosensory systems control hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. At least one includes anion-channel activation as an important component. The present results indicate that elements of the photosensory systems controlling hypocotyl growth are important to the blue-light-induced accumulation of anthocyanins in Arabidopsis seedlings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth and Medium Composition

Seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Landsberg) were sown on 0.8% agar containing 1 mm CaCl2 and 1 mm KCl. The plates were placed in darkness at 4°C for 2 d and then irradiated with red light (2 μmol m−2 s−1) for 0.5 h at room temperature. For some experiments, the plates also contained 1% Suc. In the naringenin-feeding experiments, tt5 mutants (Shirley et al., 1992, 1995) were grown on 0.8% agar, 0.5 Murashige-Skoog salts, and 1% Suc.

When used, NPPB (Calbiochem) dissolved in DMSO, Phe (dissolved in 50% ethanol; Sigma), and naringenin (dissolved in 50% ethanol; Sigma) were added to the medium after autoclaving. The final concentration of NPPB used depended on the experiment, but the concentration of naringenin and Phe used was 100 μm. Control experiments confirmed that none of the solvents at the concentrations present in the final growth medium, which did not exceed 0.16%, affected anthocyanin accumulation or seedling growth. Seedlings were grown under blue light (65 μmol m−2 s−1, 94% of which was between 400 and 500 nm) produced by two bulbs (F20T12/BB, Phillips Lighting, Somerset, NJ) for 4 d following the cold treatment except when used for RNA blots, in which case they were grown in complete darkness for 3 d and moved to blue light for the various indicated periods. Irradiating agar plates containing NPPB for 4 d with blue light did not diminish the effects of the drug on seedlings subsequently grown on them, indicating that NPPB is stable in blue light.

Anthocyanin Extraction and Quantification

Seedlings were harvested from the agar plates, quickly weighed, and placed into microcentrifuge tubes containing 350 μL of 18% 1-propanol, 1% HCl, and 81% water. The tubes were placed in boiling water for 3 min (Lange et al., 1970) and then incubated in darkness for at least 2 h at room temperature. After a brief centrifugation to pellet the tissue, 250 μL of the solution was removed and brought to a final volume of 550 μL by adding solvent. The amount of anthocyanins in the resulting extract was quantified spectrophotometrically. The values are reported as A535 − 2(A650) g−1 fresh weight (Lange et al., 1970).

RNA Extraction and Blot Analysis

Seedlings grown in complete darkness for 3 d were treated with blue light for 0, 24, or 72 h before being frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated from frozen seedlings by using a total RNA kit (RNeasy, Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). RNA was loaded onto a denaturing agarose gel, electrophoresed, transferred to a nylon membrane (Micron Separations, Westboro, MA), and hybridized with radioactive, random-primed DNA probes prepared using the cDNA of the indicated genes as a template. The cDNAs were obtained from Dr. Frederick Ausubel (CHS; Feinbaum and Ausbel, 1988), Dr. Brenda Shirley (CHI and DFR; Shirley et al., 1992), and Dr. Keith Davis (PAL1 gene-specific probe; Wanner et al., 1995). To standardize the signal in each lane, a DNA probe complementary to rRNA (Delseny et al., 1983) was also hybridized to the membrane. Hybridization signals from each probe were quantified with a phosphor imager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA), and the amount of mRNA relative to rRNA was determined for each gene.

Protein Extraction and Immunodetection

Seedlings grown for 4 d in blue light on agar medium containing 1% Suc, 1 mm CaCl2, and 1 mm KCl were harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen, ground in 1× SDS sample buffer, and boiled for 15 min. Protein samples were quantified by a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad), and separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel before blotting to a nitrocellulose filter (Bio-Rad). Equal loading was verified by staining a blot with Ponceau S (Sigma). Blots were probed with polyclonal antibodies raised against CHS (Burbulis et al., 1996), CHI, and F3H that were obtained from Dr. Brenda Shirley (Virginia Polytechnic Institute, Blacksburg) and then with peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-chicken IgY (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, West Grove, PA). The chemiluminescence produced by the secondary antibody (enhanced chemiluminescence, Amersham) was detected by radiographic film.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Anion-Channel Blocker Inhibits Anthocyanin Accumulation Induced by Blue Light

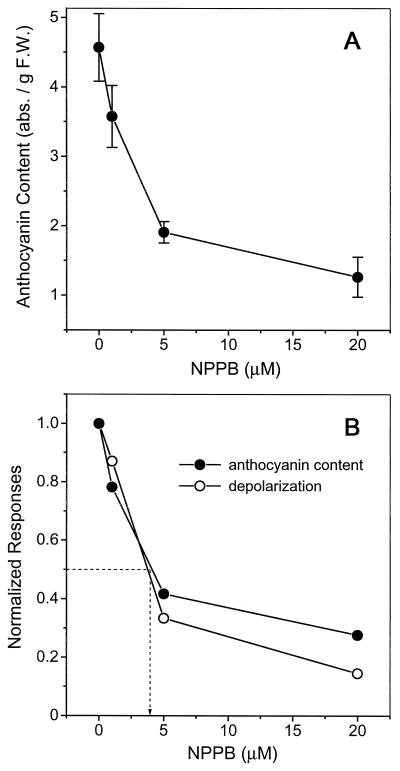

The starting point for the present work was the observation that NPPB, a pharmacological blocker of the blue-light-activated anion channel in Arabidopsis (Cho and Spalding, 1996), inhibited the accumulation of anthocyanins by seedlings grown in blue light. Figure 2A shows that the anthocyanin content of blue-light-grown seedlings was reduced by 72% when 20 μm NPPB was included in the agar growth medium. Approximately 4 μm NPPB produced half-maximal inhibition (Fig. 2B). The straightforward interpretation of this result is that NPPB blocked the anion channel, preventing transduction of the blue-light stimulus beyond the channel-activation stage.

Figure 2.

The inhibition of anthocyanin accumulation by NPPB. A, Wild-type seedlings grown in blue light on agar containing the indicated concentrations of NPPB (means ± se; n = 3–5). B, Comparison of the inhibitory effects of NPPB on blue-light-induced anthocyanin accumulation and membrane depolarization. The data in A and previously published data on the blue-light-induced membrane depolarization were normalized to the control value (0 μm NPPB) and plotted against NPPB concentration. The dashed line indicates the concentration of NPPB that produced half-maximal inhibition. abs., Absorbance; F.W., fresh weight.

However, NPPB may have inhibited anthocyanin accumulation by affecting some unrelated component of the response. A comparison of the inhibitory effects of NPPB on blue-light-induced anthocyanin accumulation and anion-channel activation would address this potentially misleading alternative. If the concentrations of NPPB required to block the membrane depolarization and anthocyanin accumulation differed significantly, a causal relationship between the two would be doubtful. Normalizing the data in Figure 2A relative to the control value (0 NPPB) and plotting them against NPPB concentration (Fig. 2B), along with similarly normalized depolarization data obtained by Cho and Spalding (1996) revealed that the two responses were very similarly sensitive to the drug. The close agreement of the two curves in Figure 2B, particularly the essentially identical values for the half-maximal-inhibition concentration, is consistent with the target of the drug being the anion channel in both cases; blocking the anion channel appears to prevent blue light from inducing the accumulation of anthocyanins.

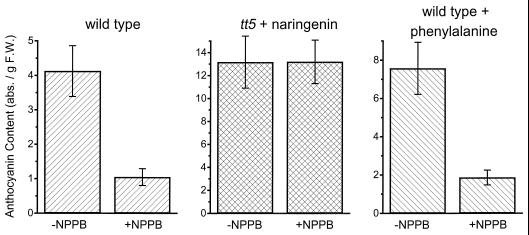

Anion Channels Influence the Anthocyanin Pathway between Phe and Naringenin

The tt5 mutant of Arabidopsis lacks detectable CHI protein (Fig. 1) and is unable to produce anthocyanins unless supplied with the intermediate naringenin (Shirley et al., 1992, 1995). We verified that tt5 seedlings grown in the absence of naringenin did not accumulate detectable levels of anthocyanins in our blue-light conditions, but when supplied with 100 μm naringenin, anthocyanins accumulated to greater than wild-type levels (Fig. 3). NPPB (20 μm) did not reduce the levels of anthocyanins in tt5 seedlings fed naringenin (Fig. 3). This result is evidence that neither the conversion of naringenin into anthocyanins nor the vacuolar accumulation of anthocyanins is impaired in NPPB-treated seedlings. Instead, NPPB appears to affect one or more of the steps that lead to the production of naringenin.

Figure 3.

Identification of the biosynthetic step(s) affected by NPPB. NPPB inhibited anthocyanin accumulation in wild-type seedlings fed Phe to the same degree as controls, indicating that one or more steps downstream of PAL was affected. NPPB did not inhibit naringenin-dependent anthocyanin accumulation in tt5 seedlings, indicating that steps downstream of CHI were not affected by NPPB. The results displayed are averages ± se; n = 4. abs., Absorbance; F.W., fresh weight.

The three genes in Arabidopsis that encode PAL provide a point for carbon to enter the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 1). Unfortunately, no mutants lacking PAL activity are known, so narrowing down the site of NPPB action with an experiment directly analogous to the tt5 experiment was not possible. However, we observed that wild-type seedlings supplied with exogenous Phe accumulated anthocyanins above the control levels, presumably because more substrate was present at the head of the pathway. Contrary to the naringenin-feeding experiment, NPPB blocked anthocyanin accumulation by Phe-fed seedlings with typical effectiveness (Fig. 3). This result would seem to rule out the possibility that NPPB inhibited anthocyanin accumulation (Figs. 2 and 3) by slowing the production of Phe or by shunting it into a competing pathway, such as the protein-synthesis pathway. Instead, the results shown in Figure 3 may be taken as evidence that the up-regulation by blue light of one or more steps between and including PAL and CHI was inhibited by NPPB. We observed variable results when seedlings were fed the intermediates cinnamate or 4-coumarate in analogous experiments, so we cannot safely pinpoint the NPPB-affected site(s) at present.

CHS, often referred to as the key enzyme in the pathway, catalyzes the first committed step in anthocyanin biosynthesis (Martin, 1993). Its place in the pathway is immediately upstream of CHI (Fig. 1). Although it is not known whether CHS (or any other enzyme in the pathway) is truly rate limiting (Martin, 1993), its expression is strongly induced by blue light (Feinbaum et al., 1991; Kubasek et al., 1992; Ahmad et al., 1995; Jackson and Jenkins, 1995; Batschauer et al., 1996), and many studies have shown its expression to be well correlated with anthocyanin levels regardless of the inducing agent (Chappell and Halbrock, 1984; Weiss et al., 1990; Deikman and Hammer, 1995; Tamari et al., 1995). We hypothesized that the blue-light induction of CHS and/or other genes in the pathway depends upon anion-channel activation. If true, this would provide a transcription-based explanation for the inhibition of anthocyanin accumulation by NPPB, and place the anion channel in a signaling pathway that reaches the nucleus to affect gene expression.

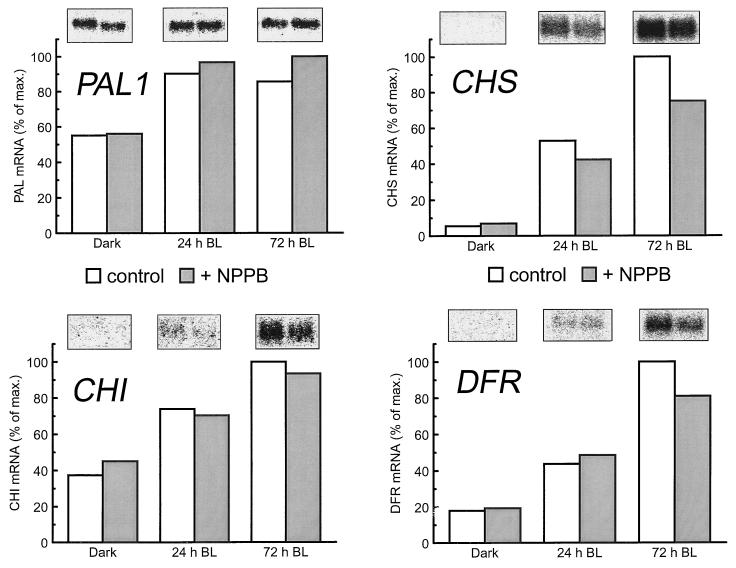

Effect of NPPB on the Expression of Anthocyanin-Biosynthetic Genes

The mRNA levels of genes encoding four enzymes of the biosynthetic pathway were measured in seedlings grown in the presence or absence of NPPB. The RNA blots in Figure 4 demonstrate that blue light increased the amount of mRNA encoding PAL1, CHS, CHI, and DFR. In particular, after 72 h of growth in blue light, CHS mRNA was increased approximately 18-fold over that of seedlings grown for the same length of time in complete darkness. This increase is consistent with the findings of others (Feinbaum et al., 1991; Kubasek et al., 1992). The blue-light-induced increase in these same mRNAs was only slightly different in seedlings grown in the presence of 20 μm NPPB. We obtained no evidence that NPPB reduced the transcript levels for the measured genes to an extent that approached its inhibitory influence on anthocyanin accumulation. In the case of CHS mRNA, 72 h of blue light induced an 11-fold increase in NPPB-treated seedlings (Fig. 4). In an experiment that used 1.5-h blue-light treatments, the same pattern of transcript levels was observed, although the absolute levels were lower (data not shown).

Figure 4.

The effect of NPPB on the blue-light-induced increase in PAL, CHS, CHI, and DFR mRNA. RNA was isolated from seedlings harvested after the indicated period of growth in blue light (BL). Results similar to those displayed were obtained in an independent, duplicate experiment. max., Maximum.

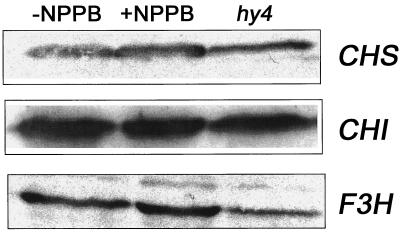

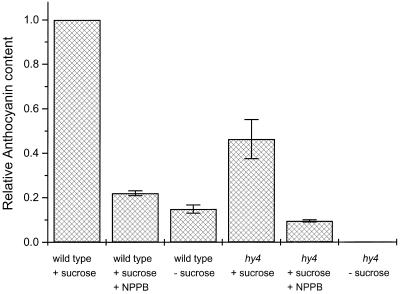

It seems improbable that the modest reductions in mRNA levels resulting from treatment with NPPB were responsible for a significant component of the drug's large inhibitory effect on anthocyanin accumulation, unless the slightly reduced mRNA levels somehow translated into substantially less protein. The effect of NPPB on the protein levels of three of the biosynthetic enzymes was determined by immunoblot assays. Figure 5 demonstrates that whether or not the seedlings were treated with 20 μm NPPB, they expressed similar amounts of CHS, CHI, and F3H. However, it is not possible to directly compare the RNA (Fig. 4) and protein (Fig. 5) analyses, because to obtain immunoblot signals well above background, it was necessary to include Suc in the growth medium.

Figure 5.

Immunoblot analysis of the effect of NPPB on the levels of CHS, CHI, and F3H protein in blue-light-grown seedlings. Consistent with the RNA blots shown in Figure 4, NPPB had no detectable effect on the above protein levels. However, lower levels could be detected in hy4 seedlings. All seedlings were grown in the presence of Suc.

Because correlations between Suc, CHS expression, and anthocyanins have been documented (Tsukaya et al., 1991), we could not safely interpret the ineffectiveness of NPPB on the protein level (Fig. 5) until we had determined that NPPB also inhibited anthocyanin accumulation in the presence of Suc. Figure 6 shows that Suc greatly stimulated anthocyanin accumulation, and that 20 μm NPPB inhibited this accumulation to the same relative extent as in the absence of Suc. Thus, Figures 5 and 6 together demonstrate that NPPB inhibited the blue-light-induced accumulation of anthocyanins without affecting the amount of CHS, CHI, or F3H protein.

Figure 6.

The effect of NPPB and Suc on the accumulation of anthocyanins by wild-type and hy4 seedlings grown in blue light. For these experiments, wild type grown in the presence of Suc is the control group to which the other treatments are compared. The results displayed are means ± se; n = 2.

When grown in blue light, hy4 displays significantly reduced CHS transcript and anthocyanin levels compared with the wild type (Ahmad et al., 1995; Jackson and Jenkins, 1995; Fuglevand et al., 1996; Ahmad and Cashmore, 1997). We found that the allele of hy4 originally isolated by Koornneef et al. (1980) and considered to be a null (Ahmad and Cashmore, 1997) also accumulated anthocyanins when grown in the presence of Suc, although less than one-half that of wild-type seedlings (Fig. 6). This decreased anthocyanin level is consistent with the lower CHS, CHI, and F3H protein levels detected in identically grown hy4 seedlings (Fig. 5), and the lower CHS mRNA reported in other studies mentioned above. NPPB further reduced the amount of anthocyanins accumulated by hy4 seedlings to a level below that of wild-type seedlings, indicating that the inhibitory effects of the drug and the mutation are additive.

CONCLUSIONS

It appears that blocking the anion channel with NPPB prevents the accumulation of anthocyanins without impairing the mechanism responsible for activating the biosynthetic genes we tested or translating their mRNAs. The portion of the biosynthetic pathway that appears to be rate limiting in plants treated with NPPB is that between and including PAL and CHI. An inference that may be drawn from these results is that induction of the biosynthetic genes and increases in the encoded proteins are not sufficient for the accumulation of anthocyanins in response to blue light. Somehow, blue light acting through anion channels at the plasma membrane may posttranslationally modify the activity of these biosynthetic enzymes. Perhaps activation of the anion channels by blue light results in a direct covalent modification, such as phosphorylation, of the enzymes to increase their specific activity. Alternatively, a modification of the cytoplasm resulting from anion-channel activation, such as a change in pH, may be important for biosynthetic activity.

The inhibitory effect of the hy4 mutation differs from that of NPPB in that it can be explained by a decrease in the transcript level of biosynthetic genes such as CHS (Ahmad et al., 1995; Jackson and Jenkins, 1995). Also, the two inhibitory effects are additive (Fig. 6). The present data led us to propose that blue light acting through the HY4 photoreceptor increases transcription of the biosynthetic genes, whereas blue light acting through the anion-channel-dependent pathway leads to an increase in the specific activity of one or more enzymes upstream of CHI. Only if both mechanisms are functional will seedlings accumulate normal levels of anthocyanins upon exposure to blue light.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Dr. Brenda Shirley at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute, Blacksburg, for generously providing us with antibodies and for helpful advice. We also thank Dr. Brian Parks and Yoo-Sun Noh for very helpful advice.

Abbreviations:

- CHI

chalcone isomerase

- CHS

chalcone synthase

- DFR

dihydroflavonol 4-reductase

- F3H

flavanone-3hydroxylase

- NPPB

5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)-benzoic acid

- PAL

Phe ammonia-lyase

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration/National Science Foundation Network for Research on Plant Sensory Systems (grant no. IBN-9416016 to E.P.S.) and by the Department of Energy/National Science Foundation/U.S. Department of Agriculture Collaborative Program on Research in Plant Biology (grant no. BIR 92-20331 to the University of Wisconsin).

LITERATURE CITED

- Ahmad M, Cashmore AR. HY4 gene of A. thaliana encodes a protein with characteristics of a blue-light photoreceptor. Nature. 1993;366:162–166. doi: 10.1038/366162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M, Cashmore AR. The blue-light receptor cryptochrome 1 shows functional dependence on phytochrome A or phytochrome B in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1997;11:421–427. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.11030421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M, Lin C, Cashmore AR. Mutations throughout an Arabidopsis blue-light photoreceptor impair blue-light responsive anthocyanin accumulation and inhibition of hypocotyl elongation. Plant J. 1995;8:653–658. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.08050653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batschauer A, Ehmann B, Schäfer E. Cloning and characterization of a chalcone synthase gene from mustard and its light-dependent expression. Plant Mol Biol. 1991;16:175–185. doi: 10.1007/BF00020550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batschauer A, Rocholl M, Kaiser T, Nagatani A, Furuya M, Schäfer E. Blue and UV-A light-regulated CHS expression in Arabidopsis independent of phytochrome A and phytochrome B. Plant J. 1996;9:63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns B, Halbrock K, Schäfer E. Fluence dependence of the ultraviolet-light-induced accumulation of chalcone synthase mRNA and effects of blue and far-red light in cultured parsley cells. Planta. 1986;169:393–398. doi: 10.1007/BF00392136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbulis IE, Iacobucci M, Shirley BW. A null mutation in the first enzyme of flavanoid biosynthesis does not affect male fertility in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1013–1025. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.6.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell J, Hahlbrock K. Transcription of plant defense genes in response to UV light or fungal elicitor. Nature. 1984;311:76–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cho MH, Spalding EP. An anion channel in Arabidopsis hypocotyls activated by blue light. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8134–8138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Jenkins GI. Distinct UV-B and UV-A/blue light signal transduction pathways induce chalcone synthase gene expression in Arabidopsis cells. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1555–1567. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.9.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl JL. Regulatory elements controlling developmental and stress induced expression of phenylpropanoid genes. In: Boller T, Meins F, editors. Plant Gene Research, Vol 8: Genes Involved in Plant Defense. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. pp. 303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Deikman J, Hammer PE. Induction of anthocyanin accumulation by cytokinins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:47–57. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delseny M, Cooke P, Penon P. Sequence heterogeneity in radish nuclear ribosomal RNA genes. Plant Sci Lett. 1983;30:107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, Pavia NL. Stress-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1085–1097. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinbaum RL, Ausubel FM. Transcriptional regulation of the Arabidopsis thaliana chalcone synthase gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1985–1992. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.5.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinbaum RL, Storz G, Ausbel FM. High intensity and blue light regulated expression of chimeric chalcone synthase genes in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plants. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;226:449–456. doi: 10.1007/BF00260658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohnmeyer H, Ehmann B, Kretsch M, Rocholl M, Harter K, Nagatani A, Furuya M, Batschauer A, Halbrock K, Schäfer E. Differential usage of photoreceptors for chlacone synthase gene expression during plant development. Plant J. 1992;2:899–906. [Google Scholar]

- Fuglevand G, Jackson JA, Jenkins GI. UVB-UVA and blue light signal transduction pathways interact synergistically to regulate chalcone synthase gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1996;8:2347–2357. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.12.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JA, Jenkins GI. Extension-growth responses and expression of flavonoid biosynthesis genes in the Arabidopsis hy4 mutant. Planta. 1995;197:233–239. doi: 10.1007/BF00202642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M, Rolff E, Spruit CJP (1980) Genetic control of lightinhibited hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Z Pflanzenphysiol Bd 100S: 147–160

- Kubasek WL, Shirley BW, McKillop A, Goodman HM, Briggs W, Ausbel FM. Regulation of flavonoid biosynthetic genes in germinating Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1229–1236. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.10.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange H, Shropshire W, Jr, Mohr H. An analysis of phytochrome-mediated anthocyanin synthesis. Plant Physiol. 1970;47:649–655. doi: 10.1104/pp.47.5.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BD, Karlin-Neumann G, Davis RW, Spalding EP. Calcium-activated anion channels and membrane depolarization induced by blue light and cold in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:1327–1334. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.4.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CR. Structure, function, and regulation of the chalcone synthase. Int Rev Cytol. 1993;147:233–284. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60770-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mol J, Jenkins GI, Schäfer E, Weiss D. Signal perception, transduction, and gene expression involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1996;15:525–557. [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus G, Bowler C, Kern R, Chua N-H. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent and independent phytochrome signal transduction pathways. Cell. 1993;73:937–952. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90272-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohl S, Halbrock K, Schäfer E. A stable blue-light derived signal modulates ultraviolet-light induced activation of the chalcone synthase gene in cultured parsley cells. Planta. 1989;177:228–236. doi: 10.1007/BF00392811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley BW, Hanley S, Goodman HM. Effects of ionizing radiation on a plant genome: analysis of two Arabidopsis transparent testa mutations. Plant Cell. 1992;4:333–347. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley BW, Kubasek WL, Storz G, Bruggemann E, Koornneef M, Ausubel FM, Goodman HM. Analysis of Arabidopsis mutants deficient in flavonoid biosynthesis. Plant J. 1995;8:659–671. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.08050659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalding EP, Cosgrove DJ. Large plasma-membrane depolarization precedes rapid blue-light-induced growth inhibition in cucumber. Planta. 1989;178:407–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamari G, Bochorov A, Atzorn R, Weiss D. Methyl jasmonate induces pigmentation and flavonoid gene expression in petunia corollas: a possible role in wound response. Physiol Plant. 1995;94:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaya H, Ohshima T, Naito S. Sugar-dependent expression of CHS-A gene for chalcone synthase from petunia in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:1414–1421. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.4.1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner LA, Li G, Ware D, Somssich I, Davis KR. The phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;27:327–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00020187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D, van Tunen AJ, Halevy AH, Mol JNM, Gerats AGM. Stamens and gibberellic acid in the regulation of flavonoid gene expression in the corolla of Petunia hybrida. Plant Physiol. 1990;94:511–515. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.2.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]