Abstract

The role of the apical shoot as a source of inhibitors preventing fruit growth in the absence of a stimulus (e.g. pollination or application of gibberellic acid) has been investigated in pea (Pisum sativum L.). Plant decapitation stimulated parthenocarpic growth, even in derooted plants, and this effect was counteracted by the application of indole acetic acid (IAA) or abscisic acid (ABA) in agar blocks to the severed stump. The treatment of unpollinated ovaries with gibberellic acid blocked the effect of IAA or ABA applied to the stump. [3H]IAA and [3H]ABA applied to the stump were transported basipetally, and [3H]ABA but not [3H]IAA was also detected in unpollinated ovaries. The concentration of ABA in unpollinated ovaries increased significantly in the absence of a promotive stimulus. The application of IAA to the stump enhanced by 2- to 5-fold the concentration of ABA in the inhibited ovary, whereas the inhibition of IAA transport from the apical shoot by triiodobenzoic acid decreased the ovary content of ABA (to approximately one-half). Triiodobenzoic acid alone, however, was unable to stimulate ovary growth. Thus, in addition to removing IAA transport from the apical shoot, the accumulation of a promotive factor is also necessary to induce parthenocarpic growth in decapitated plants.

The ovaries of nonparthenocarpic varieties do not grow normally after anthesis unless they are pollinated. The application of plant-growth regulators can substitute for pollination and induce parthenocarpic fruit development (Goodwin, 1978). In the garden pea (Pisum sativum L.), parthenocarpic growth can be stimulated by the application of GAs, auxins, and cytokinins (García-Martínez and Hedden, 1997). However, only applied GAs produce parthenocarpic fruits morphologically similar to fruits with seeds (Vercher et al., 1984; Carbonell and García-Martínez, 1985). Furthermore, the inhibition of fruit growth by inhibitors of GA biosynthesis and its reversal by applied GAs (García-Martínez et al., 1987; Santes and García-Martínez, 1995), and the correlation between the content of GAs in different tissues of fruit and the growth rate of the pod (García-Martínez et al., 1991; Rodrigo et al., 1997) suggest that GAs, probably GA1, are the hormones that control the development of the pericarp of seeded fruits.

The growth of vegetative organs competes with fruit growth, and the removal of vegetative parts enhances fruit development (Quinlan and Preston, 1971; Matsui et al., 1978; García-Martínez and Beltrán, 1992). In pea parthenocarpy can be induced by severing the shoot just above the unpollinated ovary (Carbonell and García-Martínez, 1980). The decapitation causes the diversion of GAs from mature leaves to the unpollinated ovary, which may be the cause of parthenocarpic growth (Peretó et al., 1988; García-Martínez et al., 1991). However, parthenocarpic growth after decapitation could also be due to the removal of inhibitors from the apical shoot, as occurs in the release of lateral buds (Tamas, 1995).

In this work we have investigated the role of the apex as a source of inhibitors for the growth of unpollinated pea ovaries after anthesis. We present evidence that IAA, transported basipetally from the apical shoot, prevents fruit growth in the absence of pollination. The effect of IAA on the inhibition of parthenocarpic growth is indirect and is probably mediated by ABA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plants of pea (Pisum sativum, line V1 cv Alaska type; seeds purchased originally from Asgrow, Complejo Agrícola de Semillas, Madrid, Spain) were grown in the greenhouse as described previously (García-Martínez et al., 1991). Self-pollinated flowers were tagged on the day of anthesis (d 0). Flowers were emasculated 2 d before the day equivalent to anthesis (d −2). Decapitation of the plant was performed on the day equivalent to anthesis (d 0) by cutting the internode just above the first flower (Carbonell and García-Martínez, 1980). Roots were removed at d 0 on decapitated plants by severing the stem just below the first true leaf (node 3, counting from the cotyledons as node zero), and the cut end was introduced into a vial with water, which was replenished daily.

Phloem exudate from apical shoots was obtained using the EDTA exudation technique (King and Zeevaart, 1974; Hanson and Cohen, 1985). Pea apex explants, including the youngest unexpanded leaf and 2 cm of the internode immediately below the leaf, were made when the first flower was at anthesis. The explants were cut under a solution of 10 mm Na2-EDTA and 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, and placed into 1.5-mL Eppendorf vials containing 250 μL of the same solution (one explant per vial). The explants were placed in closed boxes lined with wet filter paper and left for 24 h at 22°C in the dark. The liquid from the vials was collected and stored at −20°C until hormone analysis. The plant material for identification and quantification of hormones was frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −65°C until extracted.

Application of Plant-Growth Regulators

IAA (Sigma), (±)-ABA (Sigma), and mixtures of IAA plus [3H]IAA (851 GBq/mmol, Amersham) and (±)-ABA plus [3H]-(±)-ABA (2.00 TBq/mmol, Amersham) were applied to the plants in 1.2% agar blocks (small cylinders 6 mm in diameter and about 0.2 mL of total volume made with a 5-mL glass graduated pipette), in 0.1 m Mes buffer, pH 5.8. The agar blocks were stuck to the upper part of the severed stumps of decapitated plants at d 0. The blocks were removed after 24 h and fresh ones were applied to the stumps after renewing the cut. The agar blocks were covered with aluminum foil caps to reduce desiccation and to protect hormones from light degradation. Control plants were treated with agar blocks without hormones.

TIBA (Sigma) was applied at 0.6% (w/w) in lanolin paste containing 15% (w/v) of Tween 20. The lanolin paste was spread as a ring about 5 mm wide at the internode immediately above the first flower.

GA3 (Sigma) at different doses was applied to ovaries from emasculated flowers in 20 μL of aqueous solution at d 0.

Extraction and Purification of IAA and ABA

IAA and ABA were extracted and purified following the procedure described by Li et al. (1992) with some modifications. Frozen plant material was ground to a fine powder in a mortar with liquid N2, and homogenized with a polytron (model PT-10, Kinematica, Kriens-Luzern, Switzerland) in 80% methanol with butylhidroxytoluene (20 mg/L) (1:10, w/v), stirred overnight at 4°C, and reextracted with methanol (1:5, w/v) for 30 min. Phloem exudates were made up to 20 mL with water and adjusted to pH 3.0 before partitioning against ethyl acetate, as described below.

To check recoveries during extraction and purification [3H]IAA (about 1000 Bq) and [3H]ABA (about 1000 Bq) were added to the homogenized samples (except extracts from material treated with agar blocks containing [3H]IAA or [3H]ABA). Methanol was removed under a vacuum at 40°C, and the aqueous residue was partitioned at pH 3.0 three times against an equal volume of ethyl acetate. The aqueous phase was discarded and the pooled ethyl acetate phases were evaporated at 40°C to dryness under vacuum. The residue was dissolved in 5 mL of 70% methanol, prepared with water at pH 8.5, and passed through a C18 cartridge (Bond Elut, Varian, Harbor City, CA) washed previously with 5 mL of methanol and 10 mL of the 70% methanol solution. The column was washed with 10 mL of 70% methanol and the combined effluent and wash solutions were dried under a vacuum at 40°C.

HPLC

The residues from partially purified extracts were dissolved in 0.4 mL of 30% methanol, injected onto a 5-μm column (ODS Ultrasphere, Beckman; 25 cm long, 0.46 cm i.d.), and eluted from the column by a two-slope linear aqueous methanol gradient containing 50 μL/L acetic acid at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The first-stage linear gradient consisted of 37 to 46% methanol in 5 min, and the second of 46 to 71% methanol in 30 min, then the column was washed with methanol for 10 min. The fractions from HPLC corresponding to IAA (about 13–15 min) and ABA (about 17–19 min) were grouped according to retention times of radioactive internal standard markers and taken to dryness under vacuum. Radioactivity in HPLC fractions from transport experiments (Figs. 5 and 6) was measured by scintillation counting using scintillation liquid (OptiPhase Hisafe 3, Wallac Scintillation Products, Loughborough, Leicestershire, UK).

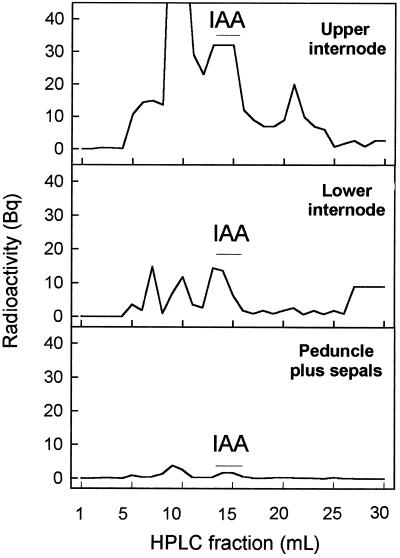

Figure 5.

Transport of [3H]IAA applied to the stumps of plants decapitated above the first flower. Agar blocks containing 10−4 m IAA plus 2100 Bq [3H]IAA were applied at d 0 and 1 to the stumps of 11 decapitated plants bearing 1 emasculated flower. The material was collected at d 2 for extraction and analysis of radioactive compounds by HPLC. The data are HPLC traces of total radioactivity recovered in the 3 cm of internode immediately above the flower, where the treatment was given (top panel), the 5 cm of internode immediately below the flower (middle panel), and the peduncles plus sepals (bottom panel).

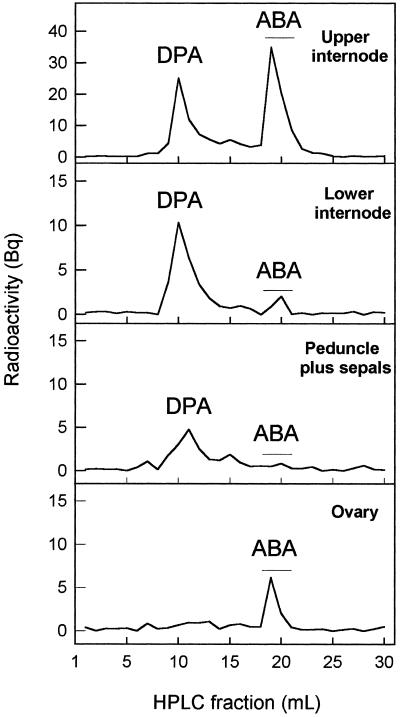

Figure 6.

Transport of [3H]ABA applied to the stumps of plants decapitated above the first flower. Agar blocks containing 10−3 m ABA plus 1300 Bq [3H]ABA were applied at d 0 and 1 to the stumps of eight decapitated plants bearing one emasculated flower. The material was collected at d 4 for extraction and analysis of radioactive compounds by HPLC. The data are HPLC traces of total radioactivity recovered in the 3 cm of internode immediately above the flower where the treatment was given (first panel), the 5 cm of internode immediately below the flower (second panel), the peduncles plus sepals (third panel), and the ovary (fourth panel). DPA, Dihydrophaseic acid.

Identification of IAA and ABA by GC-MS

Before GC-MS, the dried aliquots from pooled HPLC fractions were methylated with ethereal diazomethane for 30 min, dried under a stream of N2, transferred with methanol to 200-μL glass vials (Teknokroma, Barcelona, Spain), dried again under a vacuum, and dissolved in 5 μL of methanol.

The analyses were carried out with a gas chromatograph (model 5890, Hewlett-Packard) using a 5% phenylmethyl silicone capillary column (Ultra-2, Hewlett-Packard; 25 m long, 0.2 mm i.d., and 0.33 μm in film thickness) linked to a mass-selective detector (model 5971A, Hewlett-Packard). For IAA analysis the initial oven temperature was maintained at 60°C for 2 min, then increased at 20°C/min to 200°C, and at 4°C/min to 290°C. In the case of ABA, after 1 min at 60°C the temperature was raised at 4°C/min to 200°C, and then at 20°C/min to 250°C. The MS ion source was operated at 70 eV and 170°C, the injector temperature at 220°C, and the interface temperature at 250°C. The samples were run using full-scan acquisition mode.

Quantitative Analysis by GC-MS with Selected Ion Monitoring

For quantitative analysis appropriate amounts of [2H3]ABA and [13C6]IAA (gifts from Dr. P. Hedden) as internal standards were added to the samples at the time of extraction. The samples were purified as described above and analyzed by CG-MS in selected ion monitoring mode. The peak-area ratios of the following pairs of ions were determined to calculate the concentrations of IAA and ABA by reference to calibration curves: 130/136 and 189/195 for IAA, and 162/165 and 190/193 for ABA.

RESULTS

Growth of Pollinated and Parthenocarpic Ovaries

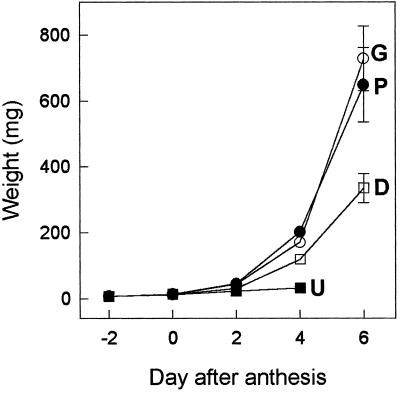

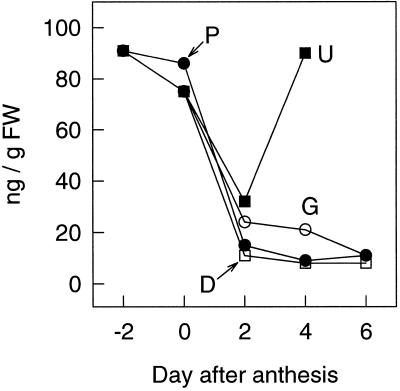

Pollinated and parthenocarpic fruits induced by GA3 had similar rates of growth and final weight, at least until d 6 (Fig. 1). Plant decapitation also stimulated the development of unpollinated ovaries, although their growth was slower and their final weight was about one-half of that of pollinated or GA3-treated ovaries (Fig. 1). Unpollinated, nonstimulated ovaries did not grow significantly after d 2 and eventually degenerated.

Figure 1.

Growth of pollinated ovaries (P), unpollinated ovaries (U), unpollinated and GA3 treated ovaries (G), and unpollinated ovaries on decapitated plants (D). Emasculation of the flowers was carried out at d −2, and decapitation of the plants and GA3 treatment (2 μg/ovary) were carried out at d 0. The bars indicate ± se.

To investigate the role of the roots and mature leaves on the parthenocarpic fruit growth after decapitation, the stem was severed at the level of the first internode and all of the leaves were removed. The excision of roots at the time of decapitation did not affect fruit set, although the final size of the parthenocarpic fruits was reduced (about 35% shorter) (Table I). On the contrary, when all of the mature leaves of decapitated plants were removed, fruit set was prevented, both in the presence and absence of roots (Table I).

Table I.

Effect of roots and mature leaves on parthenocarpic fruit development in decapitated plants

| Experiment | +

Roots

|

− Roots

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +

Leaves

|

− Leaves

|

+

Leaves

|

− Leaves

|

||||

| Fruit set | Length | Fruit set | Fruit set | Length | Fruit set | Length | |

| mm | mm | mm | |||||

| 1 | 5 /5 | 46.8 ± 1.2 | 0 /5 | 5 /5 | 31.2 ± 1.3 | 0 /5 | – |

| 2 | 4 /4 | 51.3 ± 1.1 | 0 /5 | 5 /5 | 31.8 ± 3.1 | 1 /5 | 20 |

| 3 | 5 /5 | 45.6 ± 1.0 | 0 /4 | 5 /5 | 29.8 ± 1.3 | 0 /5 | – |

Flowers were emasculated on d −2, and decapitation and removal of roots and leaves were carried out on d 0. Values were recorded on d 12, and the lengths give the means ± se. Fruit set on intact plants was always 0%. Fruit set means the number of ovaries set over the total number of ovaries per treatment in each experiment.

Effect of IAA and ABA on Parthenocarpic Fruit Growth Induced by Plant Decapitation

The application of IAA or ABA in agar blocks to the severed stump of decapitated plants counteracted the parthenocarpic growth induced by decapitation, and this inhibition was proportional to the amount of applied hormone (Fig. 2). The maximum inhibition of fruit growth by IAA was attained with 10−1 mm (about 70% weight reduction), without further effect for higher doses. ABA inhibited very efficiently both fruit set and fruit growth at 1 mm (Fig. 2). The percentage of fruit set inhibition by IAA varied between experiments but was always lower than that caused by ABA (see also Fig. 4). The growth of pollinated ovaries was also stimulated by plant decapitation, probably due to a reduced competition for photosynthates, but in this case neither IAA nor ABA applied in agar blocks (even at 1 mm) to the severed stump had any effect on fruit set and growth (data not presented).

Figure 2.

Inhibition by IAA and ABA of parthenocarpic fruit growth induced by plant decapitation. Agar blocks with different concentrations of IAA and ABA (0, 10−3, 10−2, 10−1, and 1 mm) were applied at d 0 and 1 to the severed stumps of plants decapitated at d 0. Each treatment was applied to eight plants. The weight of fruits set was recorded on d 6. Values in parentheses indicate the number of fruits set when fewer than eight. The points are average values of developed fruits ± se.

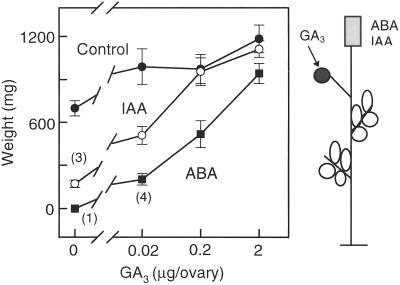

Figure 4.

Effect of GA3 on parthenocarpic fruit development on decapitated plants treated with IAA or ABA. The severed stumps were treated at d 0 and 1 with agar blocks containing IAA (10−1 mm), ABA (1 mm), or no hormone (control). GA3 (0, 0.02, 0.2, and 2 μg) was applied to ovaries on d 0. Each treatment was applied to five plants. Values in parentheses indicate the number of fruits set when less than five. The points are the means of developed fruits ± se.

The growth of the axillary bud at the leaf immediately below the first flower was measured to determine the release of apical dominance after decapitation above that flower. Severing the apical shoot at d 0 promoted the growth of axillary buds (Fig. 3). The application of IAA but not ABA to the stump counteracted the release of apical dominance (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of IAA and ABA applied in agar blocks to the severed stumps of decapitated plants on the growth of axillary buds. Decapitation was carried out at d 0, IAA and ABA were applied at d 0 and 1, and the length of the first lateral shoot immediately below the first flower was measured at d 8. The values are the means of at least seven replicates ± se. Int., Intact; C, control; I, IAA; and A, ABA.

The inhibitory effect of IAA and ABA applied to the severed stump on parthenocarpic fruit growth was negated by treating the ovaries with GA3 (Fig. 4). The IAA (10−1 mm) inhibition was fully counteracted with a dose of 0.2 μg GA3/ovary, whereas at least 2 μg GA3/ovary was required to overcome the effect of ABA (1 mm).

Identification and Quantitation of IAA and ABA in the Shoot

IAA and ABA were identified in different pea tissues by comparing full-scan mass spectra of methylated extracts with those of authentic compounds. Tables II and III present the relative abundance of the main characteristic ions for both hormones, respectively, and show that IAA and ABA were present in extracts from apical shoots (at the time of anthesis) and in 24-h phloem exudates from apical shoots. Additionally, ABA was identified in unpollinated ovaries at d 4 (Table III).

Table II.

Identification of IAA in methylated methanolic extracts and phloem exudates from apical shoots

| Plant Material | Relative Intensity of Diagnostic Ions

(m/z)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [M]+ 189 | 131 | 130 | 103 | 77 | |

| % | |||||

| Standard | 30 | 12 | 100 | 9 | 13 |

| Apical shoot | |||||

| Methanolic extract | 29 | 12 | 100 | 6 | 9 |

| Phloem exudate | 26 | 10 | 100 | 5 | 13 |

The shoots were collected at d 0 and the phloem exudate was collected for 24 h, as described in Methods.

Table III.

Identification of ABA in methylated methanolic extracts and phloem exudates from apical shoots, and in methanolic extracts from unpollinated ovaries

| Plant Material | Relative Intensity of Diagnostic

Ions (m/z)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [M]+ 278 | 260 | 191 | 190 | 162 | 134 | 125 | 112 | 91 | |

| % | |||||||||

| Standard | 3 | 5 | 8 | 100 | 30 | 29 | 42 | 11 | 14 |

| Apical shoot | |||||||||

| Methanolic extract | 1 | 5 | 12 | 100 | 31 | 25 | 46 | 11 | 17 |

| Phloem exudate | 1 | 4 | 15 | 100 | 36 | 29 | 42 | 10 | 17 |

| Unpollinated ovaries | 1 | 4 | 13 | 100 | 29 | 29 | 43 | 10 | 15 |

The shoots were collected at d 0 and the phloem exudate was collected for 24 h, as described in Methods. The ovaries were collected at d 4.

IAA and ABA were quantitated in methanolic extracts and phloem exudates of apical shoots in two independent experiments (Table IV). The total amounts of IAA (4.7–5.3 ng per organ) and ABA (approximately 2.1–2.4 ng per organ) present in the apical shoot (methanolic extracts) at time 0 were quite similar to the amounts recovered in the phloem exudates after 24 h of incubation (average values of 3.8 and 1.4 ng per organ, respectively).

Table IV.

Quantification of IAA and ABA in methanolic extract and phloem exudate of apical shoots

| Experiment | IAA

|

ABA

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanolic Extract | Exudate | Methanolic Extract | Exudate | |||

| ng/g | ng/shoot | ng/g | ng/shoot | |||

| 1 | 55 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 28 | 2.4 | 1.7 |

| 2 | 66 | 5.3 | 3.4 | 26 | 2.1 | 1.1 |

The shoots were taken at the time of anthesis of the first flower. In each experiment the phloem exudate was collected from apical shoots (nine in Experiment 1; seven in Experiment 2) incubated for 24 h at 22°C in the dark.

Transport of IAA and ABA Applied to the Severed Stump of Decapitated Plants

To determine the transport of IAA and ABA from the apical part of the plant, mixtures of radioactive (2100 Bq of [3H]IAA or 1300 Bq of [3H]ABA) and unlabeled (10−4 m IAA or 10−3 m ABA, concentrations shown previously to inhibit parthenocarpic fruit growth) hormones were applied in agar blocks at d 0 to the stumps of plants decapitated at the internode immediately above the first flower. Two (IAA) or 4 (ABA) d later, the two internodes immediately below the site of application, the peduncles plus sepals, and the ovary were collected to study the distribution of radioactivity.

In plants treated with [3H]IAA, a radioactive peak with the same HPLC elution volume as IAA and containing unlabeled IAA from the plant extract (confirmed by GC-MS) was detected in the two internodes beneath the site of treatment (Fig. 5). Other radioactive peaks of unknown nature (probably IAA conjugates and degradation products) were also observed in the chromatograms. A minor peak with the same elution volume as [3H]IAA was found in extracts from peduncles plus sepals (Fig. 5), but no radioactivity could be detected in ovary extracts (data not presented).

When the plants were treated with [3H]ABA, the extracts from the internodes and the ovary but not those from the peduncle plus sepals contained a radioactive peak with the same retention time as ABA, also coinciding with unlabeled ABA from the plant extract (confirmed by GC-MS) (Fig. 6). In addition, the chromatograms corresponding to the internodes and peduncle plus sepals but not those from ovaries contained a radioactive peak that in some cases was the major component of the chromatogram (Fig. 6). Fractions associated with this peak were combined, analyzed by GC-MS, and shown to contain the characteristic ions of dihydrophaseic acid (data not shown), a metabolite of ABA (Neill and Horgan, 1987).

Quantitation of ABA in Developing Ovaries

The application of ABA to the stump of decapitated pea plants inhibited the parthenocarpic growth of unpollinated ovaries located below the stump (Fig. 2), and [3H]ABA applied to the stump was transported into the unpollinated ovary (Fig. 6). It was also found previously that the application of ABA directly to the ovary prevents its parthenocarpic growth (García-Martínez and Carbonell, 1980). Therefore, the concentration of ABA in unpollinated, parthenocarpic (GA3-treated and those on decapitated plants), and pollinated ovaries during their early growth was determined in two separate and independent experiments. Similar results were obtained in both experiments, and data from one are presented in Figure 7. The level of ABA was relatively high at d −2 (about 80 ng/g) and decreased progressively until d 2 in all kinds of ovaries. Then the concentration of ABA remained almost constant and relatively low in growing fruits, at least until d 4. The concentration of ABA in unpollinated, nongrowing ovaries increased considerably at d 4 (to 90 ng/g), and was associated with the beginning of ovary senescence.

Figure 7.

Concentration of ABA in pollinated ovaries (P), unpollinated ovaries (U), unpollinated and GA3-treated ovaries (G), and unpollinated ovaries on decapitated plants (D) during early growth. Decapitation and GA3 treatment (2 μg/ovary) were carried out at d 0. FW, Fresh weight.

The IAA from the Apical Shoot Affects the ABA Content of Unpollinated Ovaries

As shown before (Fig. 2), the application of IAA in agar blocks to the stump of decapitated plants inhibited parthenocarpic ovary growth. This inhibition was associated with increased ABA content in the ovary: more than twice at d 1, and about five times at d 2 (Table V).

Table V.

Concentration of ABA in unpollinated ovaries growing on decapitated plants treated with agar blocks without and with IAA

| Treatment | Fresh Wt

|

ABA

Content

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d 1 | d 2 | d 1 | d 2 | |

| mg | ng/g fresh wt | |||

| −IAA | 43 | 95 | 21 | 22 |

| +IAA | 26 | 24 | 51 | 102 |

The flowers were emasculated on d − 2, the plants were decapitated on d 0, and agar blocks with 1 mm IAA were applied to the severed stump on d − 2 and − 1. The ovaries, at least 11 per treatment and day, were collected on d 1 and 2.

When TIBA (an inhibitor of auxin transport) was applied in lanolin paste at d −2 to the apical shoot of intact plants on the internode immediately above the unpollinated ovary, an approximately 50% decrease of ABA content in the ovary was found at d 0 compared with control plants (Table VI). However, the decrease of ABA content in the ovaries did not stimulate parthenocarpic fruit development, and all of the ovaries degenerated eventually. Repeated applications of TIBA to the apical shoot retarded the degeneration of the ovaries but did not promote their growth (data not presented).

Table VI.

Concentration of ABA in unpollinated ovaries on plants treated with TIBA

| Treatment | Fresh

Wt

|

ABA Content

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp.a1 | Exp. 2 | Exp. 1 | Exp. 2 | |

| mg | ng/g fresh wt | |||

| −TIBA | 13 | 18 | 158 | 80 |

| +TIBA | 19 | 20 | 69 | 48 |

Lanolin paste without (−) or with (+) TIBA (11.4 mm) was applied to the internode immediately above the unpollinated ovary on d − 2, and the ovaries (at least 20 per treatment) were collected on d 0.

Exp., Experiment.

DISCUSSION

Decapitation of the pea plant stimulates parthenocarpic growth of unpollinated ovaries (Fig. 1), which would degenerate otherwise, and the application of IAA or ABA in agar blocks to the severed stump inhibits the decapitation stimulus (Fig. 2). The inhibition by IAA or ABA was counteracted by applying GA3 directly to the unpollinated ovary (Fig. 4). We also identified IAA and ABA in the apical shoot and phloem exudates (Tables II and III), and found that both endogenous (Table IV) and 3H-labeled (Figs. 5 and 6) IAA and ABA were transported basipetally from the apex. These data indicate that IAA and/or ABA from the apical shoot may be the factor(s) that prevents the growth of unpollinated ovaries after anthesis unless, as a result of pollination and fertilization (García-Martínez and Hedden, 1997), GAs accumulate in the ovary.

The inability of IAA or ABA to inhibit the growth of pollinated ovaries when applied to the severed stump of decapitated plants may indicate that following pollination, these organs contain saturating levels of active GAs to counteract the inhibitory effect of IAA or ABA transported from the apical shoot. This is in agreement with the observation that the level of GA1 (the presumed active GA) in the pod of pollinated ovaries (approximately 1.2 ng/g fresh weight) is sufficient to stimulate the maximum growth capability of the ovary, and that the presence of higher concentrations of GA1 in the ovary (as a result of exogenous applications) does not elicit further growth (Rodrigo et al., 1997). This is probably the reason that the inhibitory effect of IAA and ABA from the apical shoot is not perceived under standard experimental conditions in the presence of developing seeds. The efficiency of the application of IAA and ABA in agar blocks to the stump is in contrast to previous results (Carbonell and García-Martínez, 1980), in which no inhibitory effect of IAA or ABA was found when applied in lanolin paste to decapitated pea plants. Clearly, the application of these hormones to a cut surface in agar (rather than in lanolin) protected from light degradation and desiccation with aluminum foil facilitates their basipetal transport in the plant.

It is not possible to decide from the data described above which are the physiological roles of IAA and ABA in the inhibition of ovary growth. The following evidence, however, indicates that IAA transported from the apical shoot controls in unpollinated ovaries the content of ABA, which would act as a secondary messenger preventing parthenocarpic fruit set and growth. It has been shown previously that the application of ABA but not IAA to unpollinated ovaries counteracts the stimulative effect of GA3 (García-Martínez and Carbonell, 1980). Also, the content of ABA in unpollinated ovaries increases if they are not stimulated by pollination or GA3 treatment, and this increase is prevented by plant decapitation (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the application of IAA to the stump enhances the content of ABA in the ovary (Table V), and the inhibition of IAA transport from the apical shoot by application of TIBA to the internode immediately above the flower decreases the ABA content in the ovary (Table VI). The observed inhibition of parthenocarpic growth by ABA when applied to the stump of decapitated plants (Fig. 2) was probably due to the basipetal transport of the applied hormone into the unpollinated ovary (Fig. 6).

The blockage of IAA transport from the apical shoot by TIBA in entire plants, although preventing the accumulation of ABA in the ovary, was not sufficient to stimulate parthenocarpy in intact plants. Therefore, both the absence of basipetal IAA transport and the presence of a promotive factor are necessary to induce fruit growth in the absence of pollination. GAs, the transport of which from mature leaves is diverted to the unpollinated ovary, where they accumulate after removing the apical shoot, have been proposed as promotive factors in the case of plant decapitation (Peretó et al., 1988; García-Martínez et al., 1991). Cytokinins can induce parthenocarpy when applied to unpollinated pea ovaries (Eeuwens and Schwabe, 1975; García-Martínez and Carbonell, 1980; Sponsel, 1982), and the transport of these hormones from the roots is under the control of IAA from the shoot (Bangerth, 1994; Li et al., 1995). However, the observation that decapitation induces parthenocarpy in the absence of roots (the main purported source of cytokinins; Chen et al., 1985), as far as the mature leaves were present in the plant (Table I), does not support the idea of cytokinins being involved in stimulating fruit growth on decapitated plants. The possibility cannot be discarded that mature leaves and/or the stem, organs also capable of cytokinin biosynthesis (Chen et al., 1985), are a source of these hormones.

The induction of parthenocarpy in pea by removing the apical shoot is similar to the apical dominance phenomenon, in which the inhibition of axillary buds is released by decapitation and negated by IAA is applied to the stump (Cline, 1991). The decapitation of the pea plant above the first flower also stimulated the growth of axillary buds (Fig. 3). Also, IAA transported basipetally from the apical shoot inhibited parthenocarpic growth without apparently entering and accumulating in the ovary (Fig. 5), as occurs in the inhibition of axillary buds (Tamas, 1995), indicating that the effect of IAA on parthenocarpy is indirect and mediated by another inhibiting factor. It is not possible to discard the possibility, however, that the absence of appreciable radioactivity in the ovary could be due to the rapid metabolization of IAA to a product lost during the purification procedure. A role for ABA in mediating the effect of IAA has also been proposed in the apical dominance phenomenon (Gocal et al., 1991). We found that the application of ABA to the stump inhibited parthenocarpic growth but had no effect on axillary bud elongation (Fig. 3). This indicates that either ABA from the shoot may not be transported into the axillary buds, or that different mechanisms operate in the inhibition of axillary buds and unpollinated ovaries by IAA transported from the apical shoot.

In conclusion, the results presented here indicate that the transport of IAA from the apical shoot prevents the parthenocarpic growth of unpollinated ovaries, and that this inhibitory effect may be mediated by ABA. Additionally, a promotive factor is also necessary for the growth of parthenocarpic fruits, which in the case of plant decapitation could be GAs and/or cytokinins transported from mature leaves.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rafael Martínez-Pardo and Antonio Villar for technical assistance in the greenhouse, Peter Hedden for the gift of 13C-labeled IAA and 2H-labeled ABA, and Isabel López-Díaz for critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviation:

- TIBA

2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica (grant no. PB93-0133 to J.L.G.-M.) and by the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia of Spain (scholarship to M.J.R.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Bangerth F. Response of cytokinin concentration in the xylem exudate of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants to decapitation and auxin treatment, and relationship to apical dominance. Planta. 1994;194:439–442. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell J, García-Martínez JL. Fruit-set of unpollinated ovaries of Pisum sativum L.: influence of vegetative parts. Planta. 1980;147:444–450. doi: 10.1007/BF00380186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell J, García-Martínez JL. Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and fruit set or degeneration of unpollinated ovaries of Pisum sativum L. Planta. 1985;164:534–539. doi: 10.1007/BF00395972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CM, Ertl JR, Leisner SM, Chang CC. Localization of cytokinin biosynthetic sites in pea plants and carrot roots. Plant Physiol. 1985;78:510–513. doi: 10.1104/pp.78.3.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline MJ. Apical dominance. Bot Rev. 1991;57:318–358. [Google Scholar]

- Eeuwens CJ, Schwabe WW. Seed and pod wall development in Pisum sativum L. in relation to extracted and applied hormones. J Exp Bot. 1975;26:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- García-Martínez JL, Beltrán JP (1992) Interaction between vegetative and reproductive organs during early fruit development in pea. In CM Karssen, LC van Loon, K Vreugdenhil, eds, Progress in Plant Growth Regulation, Kluwer Academic Press, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 401–410

- García-Martínez JL, Carbonell J. Fruit-set of unpollinated ovaries of Pisum sativum L.: influence of plant-growth regulators. Planta. 1980;147:451–456. doi: 10.1007/BF00380187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Martínez JL, Hedden P. Gibberellins and fruit development. In: Tomás-Barberán FA, Robins RJ, editors. Phytochemistry of Fruit and Vegetables. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1997. pp. 263–285. [Google Scholar]

- García-Martínez JL, Santes C, Croker SJ, Hedden P. Identification, quantitation and distribution of gibberellins in fruits of Pisum sativum L. cv. Alaska during pod development. Planta. 1991;184:53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00208236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Martínez JL, Sponsel VM, Gaskin P. Gibberellins in developing fruits of Pisum sativum cv. Alaska: studies on their role in pod growth and seed development. Planta. 1987;170:130–137. doi: 10.1007/BF00392389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gocal GFW, Pharis RP, Yeung EC, Pearce D. Changes after decapitation in concentrations of indole-3-acetic acid and abscisic acid in the larger axillary bud of Phaseolus vulgaris L. cv Tender Green. Plant Physiol. 1991;95:344–350. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.2.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin PB (1978) Phytohormones and fruit growth. In DS Letham, PB Goodwin, TJV Higgins, eds, Phytohormones and Related Compounds: A Comprehensive Treatise, Vol II. North-Holland-Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, pp 175–214

- Hanson SD, Cohen JD. A technique for collection of exudate from pea seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1985;78:734–738. doi: 10.1104/pp.78.4.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RW, Zeevaart JAD. Enhancement of phloem exudation from cut petioles by chelating agents. Plant Physiol. 1974;53:96–103. doi: 10.1104/pp.53.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CJ, Guevara E, Herrera J, Bangerth F. Effect of apex excision and replacement by 1-naphthylacetic acid on cytokinin concentration and apical dominance in pea plants. Physiol Plant. 1995;94:465–469. [Google Scholar]

- Li X, La Motte CE, Stewart CR, Cloud NP, Wear-Bagnall S, Jiang CZ. Determination of IAA and ABA in the same plant sample by a widely applicable method using GC-MS with selected ion monitoring. J Plant Growth Regul. 1992;11:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui S, Nakamura M, Torikata H. Effects of topping at different times on fruit-set and development of the first and second crops in Kyoho grapes (Vitis vinifera L. × V. labrusca Bailey) J Jpn Soc Hortic Sci. 1978;47:16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Neill SJ, Horgan R. Abscisic acid and related compounds. In: Rivier L, Crozier A, editors. Principles and Practice of Plant Hormone Analysis, Vol 1. London, UK: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 111–167. [Google Scholar]

- Peretó JG, Beltrán JP, García-Martínez JL. The source of gibberellins in the parthenocarpic development of ovaries on topped pea plants. Planta. 1988;175:493–499. doi: 10.1007/BF00393070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan JD, Preston AP. The influence of shoot competition on fruit retention and cropping of apple trees. J Hortic Sci. 1971;46:525–534. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo MJ, García-Martínez JL, Santes CM, Gaskin P, Hedden P. The role of gibberellins A1 and A3 in fruit growth of Pisum sativum L. and the identification of gibberellins A4 and A7 in young seeds. Planta. 1997;201:446–455. [Google Scholar]

- Santes CM, García-Martínez JL. Effect of the growth retardant 3,5-dioxo-4-butyryl-cyclohexane carboxylic acid ethyl ester, an acylcyclohexanedione compound, on fruit growth and gibberellin content of pollinated and unpollinated ovaries in pea. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:517–523. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.2.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sponsel VM. Effects of applied gibberellins and naphthylacetic acid on pod development in fruits of Pisum sativum L. cv. Progress No. 9. J Plant Growth Regul. 1982;1:147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Tamas IA. Hormonal regulation of apical dominance. In: Davies PJ, editor. Plant Hormones. Physiology, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 572–597. [Google Scholar]

- Vercher Y, Molowny A, López C, García-Martínez JL, Carbonell J. Structural changes in the ovary of Pisum sativum L. induced by pollination and gibberellic acid. Plant Sci Lett. 1984;36:87–91. [Google Scholar]