Abstract

Background:

Nyctanthes arbor-tristis Linn (Oleaceae) is a well-known traditional medicinal plant used throughout the India as an herbal remedy for treating various infectious and non-infectious diseases.

Objective:

To evaluate the antioxidative activity of hydro-alcoholic extract of flower in the lymphocytes exposed to oxidative stress induced by H2O2 .

Materials and Methods:

Isolated lymphocytes were treated in vitro with extract or extract+H2O2, and the level of reduced glutathione (GSH) as well as the activity of glutathione-S-transferase (GST) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were measured.

Results:

Treatment of lymphocyte with flower extract (50, 100, and 200 μg/ ml) significantly increased the level of GSH and decreased the activity of GST. The LDH activity measured in the cell-free medium decreased significantly. Pre-treatment of lymphocyte with flower extract protects the lymphocyte from the H2O2 induced oxidative stress by significantly increasing the levels of GSH as compared to the cells treated only with H2O2. Pre-treatment also reduced the activity of LDH significantly as compared to the cells treated only with H2O2. The LDH activity in cell-free medium is associated with membrane damage, the decreased levels of LDH activity reflects the reduced level of membrane damage due to H2O2.

Conclusion:

The present findings suggest the protective role of the hydro-alcoholic extracts of the flower of Nyctanthes arbor-tristis against membrane damage induced by H2O2. The results also suggest that the extract might be rich in phytochemicals with antioxidant/radical scavenging potentials, which might find application in antioxidant therapy.

Keywords: Nyctanthes arbor-tristis, oxidative stress, reduced glutathione

INTRODUCTION

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated as a metabolic by product in biological system during normal metabolism of oxygen and plays vital role in cell signaling homeostasis for maintaining normal functioning of cells.[1] In the stress conditions, either intrinsic or extrinsic, ROS levels increase dramatically, resulting imbalance in between oxidants and antioxidants that leads to various forms of damage of micro and macromolecules and finally contributes into the manifestation of disease such as sickle cell anemia, atherosclerosis, Parkinson's disease, heart failure, myocardial infarction, Alzheimer's disease, schizophrenia, cancer etc.[2–5]

Biological systems inherently have antioxidant system to scavenge and/or neutralize ROS generated under oxidative stress. Cellular antioxidant system (AOEs) consisting of mainly superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, reduced glutathione (GSH), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), reduced glutathione (GSH) etc.[6] These biological AOEs function as cascade manner to neutralize or eliminate the ROS and failure of which contributes the diseases manifestation. For effective management of reactive species, antioxidants have been supplemented, and several botanicals and synthetic compounds such as BHT, BHA have been studied for potent source of antioxidants. However, in real, biological state of radical scavenging and subsequent reduction of disease manifestation is still challenging area.[7]

Nyctanthes arbor-tristis Linn (commonly known as Night-flowering Jasmine), belonging to the family Oleaceae, is known for its extensive traditional medicinal use by the rural, mainly tribal people of India along with its use in Ayurveda, Sidha, and Unani systems of medicines.[8] Traditionally, whole plants and different parts have used as an herbal remedy for treating sciatica, arthritis, malaria, enlargement of spleen and as blood purifier. The beautiful white flowers are bitter in taste and are used as stomachic, carminative, astringent to bowel, anti-bilious, expectorant, hair tonic and in the treatment of piles and various skin diseases.[9] Recent pharmacological studies showed anti-spasmodic, antioxidant, anthelmintic, cytoprotective, anti-diabetic, anti-leishmanial, CNS depressant activity of the flower extract.[9] However, very few reports are available regarding antistress or stress scavenging activity or antioxidant activity of the flower extract of this plant. Therefore, the present study was aimed to assess the modulatory response of flower extract of Nyctanthes arbortristis on the cellular antioxidant status in lymphocytes exposed to oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and tried to correlate with oxidative stress induced membrane damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Modulator

The flowers of Nyctanthes arbor-tristis were collected from healthy plants, cleaned properly, and dried at shade at room temperature. The dried plant materials were finely powdered and macerated thrice with 80% (v/v) ethanol in shaking condition for 7 days at room temperature. The extract thus obtained were filtered and concentrated by air drying and stored at 4°C. The resulting extract was dissolved in Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) with final concentration of 2.5 mg/ml.

Lymphocytes Isolation, culture, and treatment

Anti-coagulated chicken blood, collected from source, was diluted with PBS (1:1, v/v), layered 6 ml into 6 ml Histopaque (1.077 gm/ml), centrifuged at 400 g for 30 minutes, and lymphocytes were isolated from the buffy layer. Isolated lymphocytes were then washed with 2 ml PBS and 2 ml RPMI media separately through centrifugation for 10 minutes at 250 g.[10,11] Pelleted lymphocytes were then suspended in RPMI, and viability was checked by Trypan blue exclusion method using hemocytometer.[12] Lymphocytes with viability more than 90% were used for subsequent study.

Isolated lymphocytes (200 μl) were seeded in 96 well culture plate in RPMI supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS). Lymphocytes were treated with extract (for 4 hr), and extract+H2O2 (1 hr+4 hr) as per experimental requirements and maintained at 37° C and 5% CO2 in CO2 incubator. After incubation, lymphocytes were centrifuged and washed with PBS and homogenized in PBS. The cell homogenates were used for assaying level of GSH, GST activity, and total protein content while cell free media were used for assaying LDH activity.

Reduced glutathione (GSH) Estimation

Level of reduced glutathione was estimated as total non-protein sulphydryl group in the cell homogenates after precipitating the proteins by 5% tricholoroacetic acid (TCA). The supernatant was mixed with 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 8) and 0.6 M 5, 5′-dithio-bis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) and allowed to stand for 8-10 min at room temperature. The absorbance was recorded at 412 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, UV 10), and level was calculated as nMole of -SH content/mg protein from standard curve made with reduced glutathione (GSH) and finally expressed as percentage change of GSH level.[13]

Glutathione- S -transferase (GST) activity

The specific activity of cytosolic GST was determined spectrophotometricaly (Cecil Aquarius, 7000 series) by measuring the CDNB-GSH conjugates formation at 340 nm for 3 min. The reaction mixture (1 ml) was prepared by mixing 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.5), 1 mM CDNB in 95% ethanol, and 1 mM GSH followed by incubation at 37°C for 5 min prior to measuring OD. The specific activity of GST was calculated using the extinction coefficient 9.6 mM-1 cm-1 at 340 nm and expressed in terms of percentage change of μ mole of CDNB-GSH conjugates formed/ min/mg proteins.[14]

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) activity

The specific activity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the medium was assayed by measuring the rate of oxidation of NADH at 340 nm using a spectrophometer (Cecil Aquarius, 7000 series). Briefly, assay mixture consists of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 0.5 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM NADH, and enzyme sample. The enzyme activity was calculated using extinction coefficient 6.22 mM-1 Cm-1 and finally expressed as percentage change of LDH activity.[15]

Protein Estimation

The amounts of protein present in the sample were estimated using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as standard by using Folin reagent.[16]

Statistical Analysis

All the results are expressed as means±SD. Results were statistically analyzed by student's t test for significance difference between group mean using GraphPad software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The use of natural products in the form of crude preparation and active principle as a therapeutic regime has been widely established. Several medicinal plants have been studied for their potentials to modulate cellular antioxidants and free radicals, and a numbers of active principles have also isolated from plants with anti-oxidative efficacy.[17,18] But, there is still lack of magic principle with maximum efficacy and least toxicity. The present study explores the anti-oxidative activity of flower extract of Nyctanthes arbor-tristis, a traditional medicinal plant of India against H2O2 -treated lymphocytes.

H2O2 is weak oxidizing agent and can easily cross cell membranes and inside the cell, H2O2 probably reacts with Fe 2+ and Cu 2+ ions to forms hydroxyl radicals.[19] Increased level of hydroxyl radicals in the cell subsequently cause damage to the cells by interacting with micro and macro molecules. It also inactivate enzymes directly, usually by oxidation of essential thiol (-SH) groups.[20] Our previous study established the detrimental effects of H2O2. Treatment of lymphocyte with H2O2 decreases the viability of cells by lowering cellular antioxidant, reduced glutathione (GSH).[21]

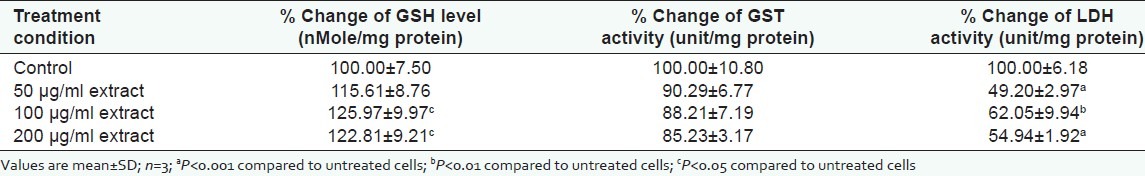

In the present study, the level of GSH increased significantly when lymphocytes were treated with flower extract of Nyctanthes arbor-tristis for 4 hours, and at 200 μg/ml of treatment, 1.22-fold increase was observed in comparison to untreated lymphocytes [Table 1]. In contrast to GSH, the specific activity of glutathione-S-transferase, an important constituent of phase II drug metabolizing enzymes declined; however, the decline was non-significant [Table 1]. For the similar treatment condition, the specific activity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), marker of membrane damage was significantly declined in comparison to untreated lymphocytes [Table 1]. This decrease in the activity of LDH suggests non-toxic effect of the extract on the cellular system; rather it might have decreased the endogenous cellular injury (as a part of normal cellular metabolism).[22,23] These data clearly showed the anti-oxidative property of the crude extract used for the current study.

Table 1.

Modulatory effects of the flower extract of Nyctanthes arbor-tristis

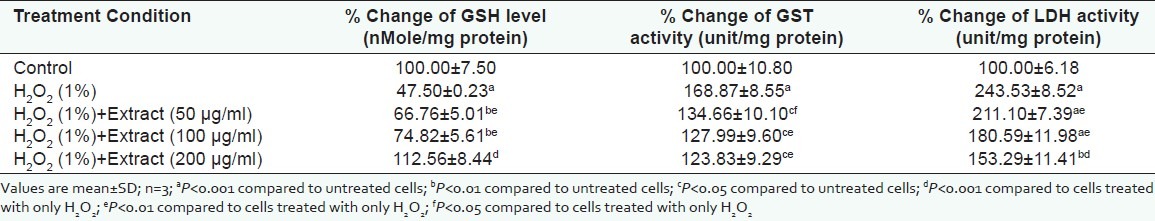

Increased level of cellular antioxidants is known to provide protection against oxidative stress.[24] Here, in our study, pre-treatment of lymphocytes with the flower extract (50, 100, and 200 μg/ml) for 1 h significantly restored the depleted GSH level in the 1% H2O2 -treated lymphocytes (4 h) [Table 2]. The restoration of GSH level at 200 μg/ ml treatment condition [Table 2] was above the untreated lymphocyte (P<0.001). As expected, the specific activity of GST decreased significantly as compared to the cells treated with H2O2 [Table 2]. GSH is co-factor of GST and is responsible for the redox status of cell. The rise in the levels of GSH is due to decreased GST activity.[25,26] The significant decrease in the activity of LDH was observed in the lymphocytes pre-treated with flower extract followed by H2O2 treatment. The significant decline in the activity of LDH suggests protective function of the extract against membrane damage induced by the H2O2.[27]

Table 2.

Protective effects of flower extract of Nyctanthes arbor-tristis in H2O2 (1%) treated lymphocytes

In conclusion, the results of the present study clearly indicate the anti-oxidative and protective role of hydro-alcoholic extract of Nyctanthes arbor-tristis against the oxidative stress induced by H2O2. The encouraging results shown by the hydro-alcoholic extract might be due to the presence of high content of phytochemicals and merits detail pharmacological investigation in suitable model to identify and characterize the active principle responsible for the observed activity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors expressed their gratitude to Prof. S K Borthakur (Dept of Botany, Gauhati University, Gauhati, Assam, India) for his help in the identification of the plant specimen. The author AH is thankful to DST, Govt. of India for financial support in the form of INSPIRE JRF.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wijeratne SS, Cuppett SL, Schlegel V. Hydrogen peroxide induced oxidative stress damage and antioxidant enzyme response in Caco-2 human colon cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:8768–74. doi: 10.1021/jf0512003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matés JM, Sánchez-Jiménez FM. Role of reactive oxygen species in apoptosis: Implications for cancer therapy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;32:157–70. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dash DK, Yeligar VC, Nayak SS, Ghosh T, Rajalingam D, Sengupta P, et al. Evaluation of hepatoprotective and antioxidant activity of Ichnocarpus frutescens (Linn) RBr on paracetamol-inuduced hepatotoxicity in rats Trop J Pharm Res. Trop J Pharm Res. 2007;6:755–65. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordberg J, Arnér ES. Reactive oxygen species, antioxidants and the mammalian thioredoxin system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:1287–312. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waris G, Ahsan H. Reactive oxygen species: Role in the development of cancer and various chronic conditions. J Carcinog. 2006;5:14–22. doi: 10.1186/1477-3163-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hazarika N, Singh P, Hussain A, Das S. Phenolics content and antioxidant activity of crude extract of Oldenlandia corymbosa and Bryophyllum pinnatum. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci. 2012;3:297–303. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasmal D, Das S, Basu SP. Phytoconstituents and therapeutic potential of Nyctanthes arbor-tristis Linn. Pharmacogn Rev. 2007;1:344–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandhar HK, Kaur M, Kumar B, Prasher S. An update on Nyctanthes arbor-tristis Linn. Int Pharm Sci. 2011;1:77–86. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winchester RJ, Ross G. Methods for enumerating lymphocyte populations. Man Clin Immunol. 1976:64–76. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thorsby E, Bratlie A. A rapid method for preparation of pure lymphocyte suspensions. Histocompat Test. 1970:665–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lechón MJ, Iborra FJ, Azorín I, Guerri C, Piqueras JR. Cryopreservation of rat astrocytes from primary cultures. Methods Cell Sci. 1992;14:73–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moron MS, Depierre JW, Mannervik B. Levels of glutathione, glutathione reductase and glutathione S-transferase activities in rat lung and liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;582:67–78. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habig WH, Pabst MJ, Jakoby WB. Glutathione S-transferases.The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:7130–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergmeyer HU, Bent E. Verlag: Academic Press; 1971. Methods of Enzymatic Analysis; pp. 5574–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miguel MG. Antioxidant activity of medicinal and aromatic plants.A review. Flavour Fragr J. 2010;25:291–312. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishnaiah D, Sarbatly R, Nithyanandam R. A review of the antioxidant potential of medicinal plant species. Food Bioprod Process. 2011;89:217–33. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halliwell B, Gutterridge JMC. Clarendon: Oxford; 1993. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine; p. 419. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yermilov V, Rubio J, Becchi M, Friesen MD, Pignatelli B, Ohshima H. Formation of 8-nitroguanine by the reaction of guanine with peroxynitrite in vitro. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:2045–50. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.9.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramteke A, Hussain A, Kaundal S, Kumar G. Oxidative Stress and modulatory effects of the root extract of Phlogacanthus tubiflorus on the activity of Glutathione-S-Transferase in Hydrogen Peroxide treated Lymphocyte. J Stress Physiol Biochem. 2012;8:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahiru D, William ET, Nadro MS. Protective effect of Ziziphus mauritiana leaf extract on carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury. Afr J Biotechnol. 2005;4:1177–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pardhasaradhi BV, Reddy M, Ali AM, Kumari AL, Khar A. Differential cytotoxic effects of Annona squamosa seed extracts on human tumour cell lines: Role of reactive oxygen species and glutathione. J Biosci. 2005;30:237–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02703704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salganik RI. The benefits and hazards of antioxidants: Controlling apoptosis and other protective mechanisms in cancer patients and the human population. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20:464S–472S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2001.10719185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rouach H, Fataccioli V, Gentil M, French SW, Morimoto M, Nordmann R. Effect of chronic ethanol feeding on lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation in relation to liver pathology. Hepatology. 1997;25:351–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramteke A, Prasad SB, Kumar S, Borah S, Das RK. Leaf extract of extract of Phlogacanthus tubiflorus Nees modulates glutathione level in CCl 4 treated chicken lymphocyte. J Assam Science Society. 2007;47:20–4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dash R, Acharya C, Bindu PC, Kundu SC. Antioxidant potential of silk protein sericin against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in skin fibroblasts. BMB Rep. 2008;41:236–41. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2008.41.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]