Abstract

Advances in the treatment of diabetes have led to an increase in the number of injectable therapies, such as human insulin, insulin analogues, and glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues. The efficacy of injection therapy in diabetes depends on correct injection technique, among many other factors. Good injection technique is vital in achieving glycemic control and thus preventing complications of diabetes. From the patients’ and health-care providers’ perspective, it is essential to have guidelines to understand injections and injection techniques. The abridged version of the First Indian Insulin Injection technique guidelines developed by the Forum for Injection Technique (FIT) India presented here acknowledge good insulin injection techniques and provide evidence-based recommendations to assist diabetes care providers in improving their clinical practice.

Keywords: Aspart, compliance, diabetes, detemir, education, glargine, glulisine, injection technique, insulin, insulin analogues, injection sites, lispro, Injections, lipohypertrophy, needle length, skin fold, storage

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of diabetes is rising at an alarming rate.[1] Recent studies report a prevalence of 62.4 million Indians with diabetes.[2] Insulin is the mainstay of treatment,[3] and approximately 1.2 million Indians inject insulin.[4] If injection technique is incorrect, there is a high risk of poor glycemic control. If needles are reused, or used improperly, it can result in pain[5,6] with bleeding and bruising, chances of breaking off and lodging under the skin, risk of contamination, dosage inaccuracy, and lipohypertrophy.[7] Hence, injection technique is an important part of insulin therapy.

The need for guidelines

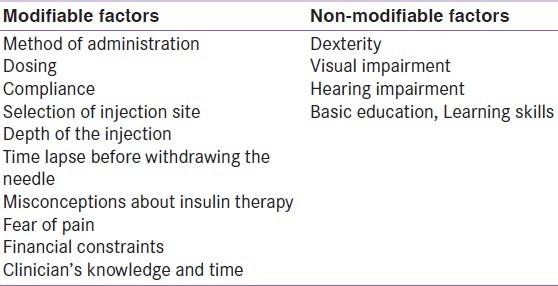

Injection technique is critical to the therapeutic success of insulin and is highly operator-dependent. The factors influencing injection technique are shown in Table 1.[8–10]

Table 1.

Factors influencing injection technique

Physician's lack of knowledge, time constraints, and scarcity of guidelines adapted to local needs could be possible reasons contributing to such factors.[11] Guidelines are needed to ensure that the modifiable factors listed above are optimized, and that correct prescription of insulin technique is provided.

The need for Indian guidelines

Consensus statements or recommendations that suit the needs of developed countries are available. However, their applicability to India and other developing countries is limited. Health-care practices in India are mostly hospital-or physician-specific rather than ‘guideline’ specific. Need for pre-injection assessment and counseling, psychotherapy for trypanophobia/belonephobia (fear of pain), techniques of motivational interviewing and behavioral change counseling, improvising techniques in resource-challenged settings to achieve cost containment and greater acceptability are not touched upon in existing guidelines. Patients get their injection supplies from various sources, and often accept whatever syringes are available. Rarely do health-care professionals mention the appropriate devices in their prescriptions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The work on the First Indian Insulin Injection technique guidelines developed by the Forum for Injection Technique (FIT) India started with the first draft prepared by a core group of four members, which was finalized after consensus approval and validation by a board of 13 health-care professionals. Simultaneously the draft was also reviewed by 75 clinicians from India and 6 clinicians from the Indian subcontinent (South Asian referee group). An abridged version of the above guidelines developed by FIT is presented here.

The evidence in these guidelines was collated from published literature specific to the subject of injection technique. Evidence was graded based on the grading method followed by Frid et al., in 2010, which included an ABC scale for the strength of recommendation and 123 scales for scientific support: A- Strongly recommended, B – Recommended, C - Unresolved issue; 1- At least one randomized controlled study, 2- At least one nonrandomized (or non-controlled or epidemiologic study), 3 - Consensus expert opinion based on extensive patient experience.[12]

In general, these recommendations apply to the majority of injecting patients; however, there will inevitably be individual exceptions for which these rules must be adjusted. Only Grade A and B1 and 2 recommendations are listed in this paper. The full list of recommendations can be found in the full text of First Indian Insulin Injection Technique guidelines, available on FIT website.

INJECTION TECHNIQUE RECOMMENDATIONS

PRE-INJECTION ASSESSMENT

Clinical assessment

A thorough patient assessment should precede therapy initiation.[13] Concerns with regard to dexterity problems, injection anxiety, misconceptions, denial of the benefits of timely injections, vision and hearing impairments, and other barriers are to be checked for (B3).[13,14]

Environmental assessment

It should be ensured that correct type and device of insulin is used. As insulin is sensitive to extreme temperatures,[15] it is essential to enquire as to what kind of conditions the injection supplies have been stored in (B2). If injection cold storage facilities are not readily available, insulin pens can be used instead of vials (C1).

Sociocultural assessment

Socio-cultural sensibilities should be respected. In Indian women the choice of injection site should be discussed beforehand.

PRE-INJECTION COUNSELING

More than one-quarter of patients may refuse insulin therapy once it is prescribed.[16] Little is actually known about this phenomenon, often termed as psychological insulin resistance (PIR). Giving the patients a sense of control over their treatment plan, and usage of devices which help reduce pain, improves acceptance.[12]

Children

In childhood, the diagnosis of diabetes itself creates a sense of distress and anxiety in both parents and children. This hinders parents’ ability to administer insulin or encourage children themselves to administer insulin (A1). It is important to include the child and the parents as important partners in diabetes care. The attention of child should be diverted or if required, cognitive behavioural therapies (relaxation training, guided imagery, graded exposure, active behaviour rehearsal, modelling and reinforcement, and small incentives) have to be employed (A2). Explanation of role of insulin in diabetes management and need for regular injections, using simple and clear words, helps allay their misconceptions and concerns (A2).

Adolescents

In adolescents, peer pressure, lack of seriousness, pain, and frustration may prevent them from adhering to injection schedule. Fear of weight gain, especially among girls, might lead to skipping of injections. It is important to help adolescents overcome any possible misconceptions related to insulin injection by sharing information with them (A2). Positively reinforcing their commitment to diabetes care helps them realize their key role and ensure their active participation (B1). Clinicians should avoid use of terms which might show that such a therapy is a failure, a form of punishment or threat (A3).

Adults

While adults are expected to be easy to handle and well prepared to take injections, this is usually not the case. Educate all newly-diagnosed patients about the course of diabetes and the need to start insulin therapy (A3).[12] Interference with the quality of life, worsening of diabetes condition, failure to self-manage the disease, guilt, daily injections, and hypoglycaemia are some of the major factors that could pose challenge in on-going diabetes care. Helping the patient understand that having such concerns is not unusual encourages them to discuss these issues and find solutions (A3).

INJECTION STORAGE

Specific storage guidelines given by the manufacturer should be followed (A1). Insulin pens and vials not in use are to be refrigerated at a temperature of 4-8°C, but not frozen (A1).[15] If insulin is frozen, it should be discarded (A1). Insulin should be stored in a cool and dark place at room temperature (15–25° C) and discarded 30 days after initial use or as per manufacturer's instructions (A1). It must be remembered that the room temperature may cross 40°C in some parts of India during summer. Extremes of temperature (direct sunlight, kitchen, top of television/other electronic devices) should be strictly avoided (A3). If the vial is kept in a refrigerator, it should be taken out and kept at room temperature for at least 30 minutes before injecting.[17] Pens should never be stored with needles attached.[7] If a refrigerator is not available, the vial can be labelled using water proof stickers and placed in an water-filled earthen pitcher.(B3)Never use insulin beyond expiry. Insulin should be kept out of reach of children (A1).

Travel–surface

While travelling, insulin should be kept in a flask with ice, or in a hand bag, or in a proper container if the outside temperature is >30°C. Insulin should never be kept in the glove compartment of a car.[15]

Travel–air

Ensure that sufficient injection supplies are carried. Carry doctor's prescription. Time zone changes of two or more hours may necessitate a change of injection schedule. Never place insulin in the baggage hold of the plane to avoid freezing.[18] Patients who are using pens with cartridges should carry a spare pen or vial to ensure uninterrupted insulin delivery in the event of device breakdown/malfunction.

DEVICE SELECTION AND USE

Prior to injection, the patient must verify expiration date and the dose, and if the correct type of insulin is being readied for injection (A1). Expiry dates of insulin vials or pens after opening can vary significantly depending on the type of insulin. The choice of injection device, needle length and gauge, and type of insulin syringe into the prescriptions should be emphasized (A1). Examine the insulin bottle and ensure there are no changes in insulin (e.g., clumping, frosting, altered color or clarity) (A1). Re-suspension of cloudy insulin is important to ensure proper absorption of injected insulin and for the maintenance of appropriate concentrations of the remaining insulin. (A2).[13] They must be gently rolled and/or tipped (not shaken) for 20 cycles until the solution becomes milky white (A2).

Syringe and vial compatibility

It is important to inject the right insulin strength with the right insulin syringe.[19] In India, both 40 U/mL and 100 U/ mL insulin types are available. At the time of initiating a patient on insulin, it is important to inform them to use U100 vials with U100 insulin syringes and U40 vials with U40 insulin syringes only. Insulin syringes of U100 have an orange cover and black scale markings denoting two units each, while U40 syringes have a red cover and red scale markings denoting one unit each.[20]

Needle size

Needle lengths for syringes are available in three sizes 6 mm, 8 mm, and 12.7 mm. Insulin syringe gauges are available in 31, 30 and 29 gauges, respectively. The 31 gauge is available in both 6 and 8 mm needle lengths.[21]

Pens and pen needles

Insulin pens carry insulin in a self-contained cartridge.[22] There are different models available, including reusable (cartridge can be reloaded) and disposable pens (discarded once emptied)[23] Points to be noted while selecting a pen include:[23]

Types and brands of insulin that are available for the pen

The number of insulin units the pen holds when it is full

The largest dose that can be injected with the pen

Dose adjustments possible (two-, one- or half-unit increments)

Indication to decide whether or not there is enough insulin left in the pen for the entire dose

Style, appearance, and material of the pen

Numbering on the pen dose dial and its magnification

The amount of strength and dexterity needed to operate the pen

Correction measures if a wrong dose is dialed into the pen

Pen needles

Pen needles are available in 4, 5, 6, and 8 mm sizes and are of 32, 31, and 30 gauges. The shorter needles are long enough to pass through the skin into the fatty layer but are short enough not to reach the muscle tissue.[24]

Needle length

The goal of a subcutaneous injection is to deliver the medication directly into the subcutaneous tissue without any discomfort or leakage. Deciding the needle length is based on multiple factors: physical, pharmacological, and psychological. Shorter needles are safer and better tolerated. In obese patients, studies have reported equal efficacy, safety/tolerability of shorter needles (4–5 mm) in comparison to longer ones (A1). Till date, no evidence reports an increase in the leakage of insulin, pain, or lipohypertrophy, or worsened diabetes management or other complications with shorter needles.[12,15] Adults do not require the lifting of a skin fold, particularly for 4 mm needles (A1). Shorter needles should be given in adults at a 90° angle to the skin surface (A1). An injection into the limbs or a slim abdomen warrants the need for a skin fold. Patients already on needles ≥8 mm should move to a shorter needle or lift a skin fold and/ or inject at 45° in order to avoid injecting into muscle.

Needle length in children

There is minimal variation in skin thickness with respect to demographic variables such as Body Mass Index (BMI). Hence, a needle of 4 mm length is considered to be safe and efficacious in patients of all age groups (A1).[25] In children, thickness of the skin is slightly less than in adults and it increases with age. Subcutaneous thickness is, however, the same in both the sexes until puberty. Later, girls gain subcutaneous mass, while in boys it declines slightly. This makes boys at a higher risk of injecting into muscles. Currently, the safest needle for children appears to be the 4-mm pen needle (A1). However, when used in children aged 2–6 years, it should be used with a pinched skin fold (A1).[26] With a 6 mm needle, an injection should be given with a skin fold or angled at 45°. If only an 8 mm needle is available, then they should lift a skin fold and inject at 45°.

INJECTION SITE

Insulin is routinely injected subcutaneously in ambulatory patients. Intravenous (IV), IV infusion, or intramuscular routes are used during ketoacidosis or stressful conditions.[27] The various injection sites include:

Anterior abdomen: Abdomen is the most common injection site.[12] The injections at the abdominal site are usually administered below a horizontal line drawn 2.5 cm above the umbilicus, and lateral to vertical lines drawn 5 cm away from the umbilicus.

Upper arm: The site includes the posterior mid-third of the arm between shoulder and elbow joint.

Anterior thigh: The preferred site is in the anterior and outer aspect of the mid-third of the thigh, between the anterior superior iliac spine and knee joint.

Buttock: Choose the upper outer quadrant of the buttock. Place your index finger on the iliac crest and make a right angle between the index finger and your thumb to locate the upper outer quadrant. The order of the rates of absorption at these sites is abdomen > arm > thigh > buttock.[28] Presence of a layer of fat and not many nerves at these regions makes injections easier.

Cleansing

The injection site should be socially clean [one should be willing to touch the skin] before the injection is given. Cleansing is the single most important procedure for preventing health-care associated infections (A3). This can be done by using cotton balls dipped in water or with alcohol swabs (A2). Start by cleaning your hands with soap and water, followed by cleansing the injection site in the middle and moving outwards in a circular motion. Make sure the skin is dry before injection.[12] It is recommended not to use soap based detergents (A3).

Skin folds

Skin folds are used when the presumptive distance from the skin surface to the muscle is less than the needle length. The thumb and index finger are used to make a proper skin fold (possibly with the addition of the middle finger) (A1).[12] Lifting the skin using the whole hand risks lifting muscle and can lead to intramuscular injections.[29] Use of a skin fold avoids soft tissue compression and injections penetrating deeper than intended (B3).[1] The lifted skin fold should not be squeezed so tightly that it results in skin blanching or pain (A3). The optimal sequence to perform a lifted skin fold should be (A3):

Make a lifted skin fold and insert needle into the skin at 90° angle

Administer insulin

Leave the needle in the subcutaneous tissue for 10 sec after the plunger has been fully depressed

Withdraw needle from the skin

Release skin fold

Injection site must be examined individually and it should then be decided whether lifting the skin fold is needed for the given length of needle (A3) and recommendation should be provided to the patient in writing along with teaching the correct technique of lifting the skin fold from the onset of injectable therapy (A3).

Systematic rotation of injection sites

Systematically rotating the injection site helps maintain healthy injection site, reduces risk of lipohypertrophy and optimizes insulin absorption. A commonly used scheme is to divide the injection site into quadrants (abdomen) or halves (thighs, buttocks, and arms). One quadrant or half should be used per week. (A3).[30] Injections within any quadrant or half should be spaced at least 1 or 2 cm apart to avoid repeat-tissue trauma (A3). Proper and consistent rotation safeguards the tissue.[12] An easy-to-follow rotation scheme should be taught at the onset (A2) and audited during every visit (A3). Poor care can lead to insulin malabsorption and lipohypertrophy.[28]

INJECTION TECHNIQUE

Syringe and vial

A syringe is the primary injecting device used in India. To inject insulin, ensure that the:

Insulin vial is taken out of refrigerator 30 min prior to injection to ensure that the insulin is at room temperature. Make sure that the expiry date has not passed and that the bottle is not damaged (A1).

If using cloudy insulin, inspect for any changes, i.e. clumping, frosting, or precipitation. Ensure that the insulin is uniformly mixed by rolling the vial between palms (A3).

Clean the top of the vial with an alcohol swab. An amount of air equal to the dose of insulin needed has to be drawn up into the syringe and injected into the vial to avoid creating vacuum (A3). Invert, and pull the plunger back gently to the number of units desired. Keeping the syringe in the upright-position, check for any air bubbles. If air bubbles are seen in the syringe, draw up several more units of insulin and re-inject the bubbles into the vial by pushing the plunger back to the desired dose marking. If bubbles are still seen, slowly push insulin back into the vial and again pull the plunger very slowly to the required number of units (A3). Repeat till no air bubbles are seen. Once the required dose is drawn into the syringe, turn the syringe and the vial back over. Holding the syringe by the barrel, carefully remove the needle straight out of the bottle.[31]

Select the right injection site. Clean the injection area with an alcohol swab. Start in the middle of the area and then moving outward in a circular motion clean the whole area. To reduce any stinging, be sure that the alcohol on the skin is completely dry before injection.

Grasp a fold of skin between the thumb and index finger and push the needle at the desired angle based on the needle length and other parameters. The needle should go all the way into the skin. Push the plunger to deliver the insulin. Count till 10 before pulling the needle out. You may have to count longer in case of heavier doses. Release the pinch up and press an alcohol swab over the injected spot. Do not massage the area (A3). Dispose of the needle and syringe after use (A1). Ideally, never reuse a needle (A2).[17,31]

Mixing Insulin

For a mixed dose, care should be taken to follow the right sequence of mixing. Regular insulin should be filled first followed by NPH Insulin. Reversal can cause impurities in the regular insulin vials. Draw air into the syringe equal to the dose of cloudy insulin desired. Insert the needle through the rubber stopper of the cloudy insulin vial, and inject the air into it; this will make it easier to draw back the insulin later. Then remove the needle without drawing up the cloudy insulin. Pull the plunger back to the dose of regular insulin desired and inject air into the clear insulin vial. This time, leave the needle in the bottle, turn the vial upside down and slowly draw the desired dose of regular insulin. If you see air bubbles in the syringe, draw up several more units of insulin and re-inject the bubbles into the vial by pushing the plunger back to the desired dose. Now remove the needle from the vial. Holding the bottle upside down, insert the needle through the rubber stopper of the cloudy insulin vial and pull plunger back to the marking that indicates total dose of insulin. Be sure you have the right number of units as the insulin cannot be pushed back into the vial.[31]

Pen

The method of device preparation for injecting insulin remains same for both reusable and prefilled disposable pens. With premixed or NPH insulin, ensure the insulin has been re-suspended by rolling the pen. Clean the edge of the pen with a swab and screw on a new pen needle. Insulin pen should be primed with two units of insulin as the first step (A3). This is then discarded and the actual dose has to be dialled in. The appropriate dose dialled can be seen on the device's display window and can be heard as audible clicks in many pens.[32] Insert the needle, push the injection button and count slowly to 10 before withdrawing the needle in order to get the full dose and prevent leakage of the medication (A1). Counting past 10 may be necessary for higher doses. Remove the pen needle from the pen and dispose safely (A2).[12] The injection site should not be massaged (A3). Needles should be disposed immediately after injection instead of being left attached to the pen (A2). This prevents entry of air into the cartridge as well as leakage of medication. Use of new needles each time reduces the risks of needle breakage in the skin, clogging of the needle, inaccurate dosing, and indirect costs (A3). Pen devices and cartridges are for single person use and never to be shared with others as it increases the risk of cross-contamination (A2).

Injection-meal time gap

Time gap between injection and meal is critical for the control of glycemic levels and for the insulin action (A1).[33] Patients should always follow the advice given by physicians regarding timing of injection. Regular insulin should ideally be taken 30 mins before meal as it has a delayed onset[34] whereas rapid-acting insulins (lispro, aspart, and glulisine) can be injected before or immediately after a meal.[35] Changing injection-meal time is a strategy used to accentuate or reduce the efficacy of insulin, and should be practiced only under the physician's guidance. NPH, detemir and glargine can be given at the same time every day, without relation to meals. For ultra-long-acting insulin (degludec), the inter-injection period can vary between 8 and 40 hours, and no specific injection to meal time gap is recommended.

Pre-mixed insulin

In general, premixed insulin preparations are available in a wide range. However, at times one has to mix rapid-/short- and intermediate- acting insulin. Patients who are well controlled on a particular mixed-insulin regimen should maintain the same standard procedure for preparing the insulin doses (A1). Regular insulin and rapid-acting analog can be mixed with NPH in the same syringe in every ratio (A2).[36] Glargine and detemir must not be mixed with any other insulin (A2). If suitable premixed insulin is available, it should be used (A1).

TROUBLESHOOTING

Pain

Pain due to insulin injection is an infrequent occurrence, unless the needle comes in contact with nerve endings. Some patients exhibit needle phobia or increased sensitivity to pain due to previous unwanted experiences. Pain can be minimized or avoided if good injection practices are followed.[12,13,37] Some ways of minimizing pain include:

Use of new needles (clean, sharp, and dry, and the right length) for each injection (A2).

Use short needles (4, 5, 6 mm) with fine gauge (A2).

Insert the needle at 90° to the skin (A2).

If large doses, consider splitting the dose (A2).

Injections in use to be kept at room temperature (A2).

Inject slowly and ensure that the thumb button/ plunger are completely depressed (B2).

Skin should be dry before injecting, if injection site cleaned with alcohol swabs (B2).

Avoid injecting in the hair roots (B2).

Lipohypertrophy

Lipohypertrophy manifests as a localized lesion at the injection site. Reuse of needles is the main cause of lipohypertrophy. Non-rotation of injection sites may also result in localized lipohypertrophy, or degeneration and atrophy. Injecting into lipohypertrophy sites may result in significantly unpredictable and delayed absorption which can lead to hyperglycemia and/or hypoglycemia.[12] Tips to prevent lipohypertrophy include:

Injection site should be inspected at every visit. The patients should be taught to inspect their own sites and be given training on how to detect lipohypertrophy (A2).

Make 2 markings at 2 opposite sides of lesion, measure size and record the readings (A3).

Change injection site every week (A2).

Never inject into the lipohypertrophic tissue till it returns back to the normal (A2).

Switching injections from lipohypertrophic tissue to normal may generally need decrease in doses. However, the amount of change varies and is based on frequent blood-glucose monitoring (A2).

Avoid reuse of injection needles (A2).

Use good quality insulin or insulin analogues from reputed manufacturers (A3).

Bleeding and bruising

Needles occasionally cause bleeding or bruising. Clinical studies reported lesser frequency of bleeding/ bruising with needles of shorter length. If bruising occurs persistently, the injection technique should be reviewed and sites with bleeding/bruising be avoided until fully recovered (A2). Patients should be assured that bleeding/bruising have no adverse clinical consequences (A2).

Trypanophobia (Belonephobia)

The fear of self-injecting insulin compromises glycemic control and emotional well-being. Likewise, the fear of pricking can be a source of distress and may seriously hamper self-management.

Physicians should try to re-establish patient's sense of personal control and suggest a brief trial of insulin therapy (A2). Patient's personal obstacles should be identified and acknowledged (A2). Psychological counselling should be considered for patients who are really needle-phobic (A2).

Needle-stick injuries

Needle stick injuries are common to patients while recapping the needle. In hospital settings, professionals should be advised against recapping a used insulin syringe (A2). Safety needles effectively protect health professionals against contaminated needle-stick injuries (B1). Education and training is needed to ensure that safety practices are followed (B3).[12]

Injection through clothing

Many patients do inject through clothing, especially when in a hurry or unable to disrobe in public. This practice should be avoided, reviewed and addressed regularly (A3), as the needle becomes unsterile and can cause infection, its lubrication gets lost, thus causing pain, it is difficult to perform a pinch-up correctly, cleaning and inspection of the site are not possible, and cloth fibers may enter and irritate the skin.

Needle/Syringe hygiene

The United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) recommend injection needles for a single use only. Syringes should ideally be used once. However, in our country, to cut down on costs, patients often reuse syringes and needles. Such patients should be counseled about potential hazards of reuse while explaining the technique of recapping the needle cover aseptically after each use [although against National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) guideline],[38] and importance of not sharing syringes between individuals. Doctors should adopt a practical approach on this issue.

When reusing, the thin tip of the needles become damaged, they get bent, and the silicone lubricant coating of the needles is also lost (A2). This results in a more painful injection, with bleeding and bruising (A2). Repeat usage can also result in breaking off and lodging of the needles under the skin. Furthermore, there is a higher chance for insulin to get deposited within the needle with reuse, making it harder to press on the plunger and deliver proper insulin doses (A2).

Reuse of needles increases the risk of contamination and infection (A2). A few patients, in an attempt to be hygienic, clean the needle with alcohol prior to reusing it. This practice removes the silicone lubricant and results in a more painful injection. This practice should be discouraged.

Needle reuse also results in increased risk of lipodystrophy (A2).

Manufacturers recommend removing insulin pen needles immediately after use. Health-care professionals should bring awareness in patients regarding the potential adversities of needle reuse, and encourage appropriate needle/syringe use (A2).

Periodic clinical audits

Clinicians must undertake a periodic audit of injection practices in their clinics. An audit helps to determine patient knowledge about insulin, and establish if patients are using the correct injection sites and correct injection technique (A2). Nurses and other health-care providers should be aware of the actions and limitations of Insulin (A2).

Injection device disposal

Guidelines developed by NACO, recommend the use of puncture proof box or safety box to collect used needles or syringes properly labeled as biohazard. The filled boxes should be disposed of at drop-in centers where disinfection and disposal of sharps is carried out (A2).[38] Needle clipping devices that remove insulin syringe needles and pen needles safely and easily can be used. Empty pen devices can be disposed in household refuse bins. Awareness of local regulations should be created among patients and health-care providers (A3).

Missing/Changing injections

Patients should be counseled about the negative effects of missing injections. In case of extreme scarcity of insulin, insulin rationing may have to be resorted to (A2). However, both physicians and patients should be made aware of the harmful effects of such a practice. If there is a change in the insulin, then the patient should be fully informed as to why there has been a change and the potential need for additional glucose monitoring (A3).

There should be no interchange made in the insulin species, type, or brand by the pharmacist or health-care provider without the approval of the prescribing physician and without the knowledge of the patient that a change is being made (A2). If a patient is admitted in the hospital and there is no awareness of which insulin the patient uses, human insulin has to be administered until further information is available (B3).

SPECIAL POPULATIONS

Pregnancy

Close monitoring is recommended in pregnancy, especially during the first trimester. Injections given in abdomen require a raised skin fold (B2).[13]

Elderly

Impairments in dexterity, cognition, vision, and hearing is very common in elderly patients (A2). Assistance by care giver is recommended and they should be educated on importance of injectable therapy, injection technique as well as prevention and treatment of hypoglycemia (A2).[13]

Sensory-motor impairment: visual, tactile and lack of manual dexterity

Nonvisual insulin measurement devices, syringe magnifiers, needle gauges, and vial stabilizers help ensure accuracy and aids in insulin delivery in individuals with visual impairment. For persons with both visual and dexterity impairment, prefilled syringes may be helpful (A2). People with low hearing ability and those who use hearing aids should be educated in a noise-free environment (A2) . The instructor should face the person with sufficient light falling on his/her face which facilitates lip-reading. Speaking slowly and clearly with normal intonation helps. In people with dexterity problems, use of injection devices with preset doses and easy featuring devices may be beneficial (A2).[13]

Immuno-compromised individuals

Insulin resistance is a major concern in immune-compromised individuals, including those with HIV and hepatitis.[39] Hence, early initiation of insulin therapy should be considered in such patients as it improves therapeutic outcomes .[40] Injections and finger sticks administered to immune-compromised patients have a high risk of blood exposure to the injector as well as health-care personnel.[41] Hence, never reuse/recap used needles, syringes, or lancets (A2).

Indoor patients/Nursing home patients

Patients sharing cold chain facilities, such as refrigerators with others, as in hospitals, nursing homes and old age homes, should label their insulin vials and pens with their names, using indelible ink (A2).

Disaster management

In Type 1 diabetes patients, not taking insulin can be life-threatening. A portable diabetes disaster kit that is insulated and water-proof should be kept ready (A3). The kit should have a supply of insulin syringes for at least 30 days and insulin vials or pens and needles along with cold packs (A2). It should also contain lancets, test strips, glucose meter (preferably two) with extra batteries and a sharps container. At least a 3 day supply of nonperishable food and bottled water is also recommended.[7]

BARRIERS TO INSULIN THERAPY

Careful identification and correction of barriers to insulin therapy is a vital step toward successful self-management of diabetes.[13]

Patient barriers

There are several myths and negative approaches that act as barriers in the use of insulin among people with Type 2 diabetes. By asking open-ended and nonjudgmental questions, physicians can help patients disclose their concerns and implement effective solutions.[13] It is important to encourage shared decision making and provide them a sense of control over their treatment.

Physician barriers

Physician-related barriers to timely initiation of insulin are often based on their perceptions of patient-related barriers including concerns about adherence, hypoglycemia and weight gain. Other factors are lack of support staff and counseling/motivational skills, and the desire to prolong oral therapy.[10,13] Physicians wrongly believe that insulin therapy is expensive, however use of insulin reduces costs by decreasing complication rates and management burden.

Health-care system barriers

Lack of resources also acts as an important barrier in insulin therapy. A financial barrier exists for patients who lack insurance.[13] For health-care providers, a key issue is the lack of trained diabetes educators. The solutions below have mainly focused on increasing availability and lowering cost.[42]

Using pens instead of syringes offers cost benefits due to improved treatment adherence and reduced health-care utilization (B3).

Provision of enhanced training on insulin injection skills to nurses, and stringent titration protocols to be followed by nonmedical practitioners (A2).[13]

Funds for hiring a diabetes educator and for setting up an education Programme (B1).

IMPROVING COMPLIANCE

Counseling forms an integral part of the management of diabetes. The methods by which one can improve compliance to injection therapy are by counseling with respect to the various patient, physician and drug related factors which include:

Drug-related: Appropriate choice of regime, flexibility of timing of injection, efficacy, safety (no hypoglycemia) and tolerability (no weight gain).

Patient-related: Empowerment, communication, health literacy and shared decision-making.

Physician-related: Competence, confidence, communication skills, accessible authenticity, simplicity, reciprocal respect and empathy.[43]

The patients should be encouraged to ask questions and clarify doubts, if any. Concerns expressed by the patients should be acknowledged as they are indicators of active patient participation in treatment process. Counseling should be personalized and information shared should be relevant from the patient's perspective. The WATER approach provides a good template to build on for this purpose.[44]

ONGOING PATIENT AND PHYSICIAN EDUCATION

Information may not be retained by patients if given in times of anxiety. It is essential to revisit all aspects of injection technique regularly. Enough time has to be provided to meet individual learning needs and the learning style of each individual has to be assessed beforehand. Information given in short sessions and regularly reinforced is more easily retained. Education content and the style of teaching has to be adjusted to individual needs.[17] A quality management process should be put in place and made sure that the correct injection technique has been practiced regularly by patients and is also documented in the record (A3).

CONCLUSION

The First Indian Insulin Injection technique Guidelines developed by have focused on the injection technique. Recommendations have been provided on various topics such as needle length selection, injection process (use of skin folds and injection angle), choice of body sites, lipohypertrophy, disposal of injecting material, and patient and physician education. These recommendations guide the health-care provider and patient towards using shorter needles and safe disposal practices. This helps in reducing the risk of contamination, increase the consistent delivery of insulin into the subcutaneous space, and achieve optimal glycemic control.

DUALITY OF INTEREST

Authors (except, the co-opted) are members of FIT (Forum for Injection Techniques) India advisory board, who have helped develop the First Indian Insulin Injection technique Guidelines. FIT India is supported by Becton Dickinson India Private Limited (BD), a manufacturer of injecting devices. Members of the FIT advisory board may have received an honorarium from BD for their participation. This document is an abridged version of the First Indian Insulin Injection technique Guidelines, developed by FIT, which is a copyright of BD, and shall be considered proprietary to BD India Private Limited, therefore limited to be disclosed or published solely by BD India Pvt Ltd.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the significant contribution made by members of the South Asian Referee Group and the Indian Review Panel.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mohan V, Sandeep S, Deepa R, Shah B, Varghese C. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes: Indian scenario. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:217–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anjana RM, Pradeepa R, Deepa M, Datta M, Sudha V, Unnikrishnan R, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes (impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance) in urban and rural India: Phase I results of the Indian Council of Medical Research-INdiaDIABetes (ICMR-INDIAB) study. Diabetologia. 2011;54:3022–7. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crasto W, Jarvis J, Khunti K, Davies MJ. New insulins and new insulin regimens: A review of their role in improving glycaemic control in patients with diabetes. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:257–67. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.067926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad R. Innovate for Diabetes in India. [Last accessed on 2012 June 01]. Available from: http://blogs.novonordisk.com/graduates/2010/10/27/innovate-for-diabetes-in-india/

- 5.Strauss K, De Gols H, Hannet I, Partanen TM, Frid A. A pan-European epidemiologic study of insulin injection technique in patients with diabetes. Pract Diab Int. 2002;19:71–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.New UK recommendations for best practice in diabetes injection technique. [Last accessed on 2012 May 05]. Available from: http://www.primarycaretoday.co.uk/training/?pid=4216andlsid=4268andedname=29301.htmandped=29301 .

- 7.Dolinar R. The Importance of Good Insulin Injection Practices in Diabetes Management. US Endocrinol. 2009;5:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meechan JG. How to overcome failed local anesthesia. Br Dent J. 1999;186:15–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gin H, Hanaire-Broutin H. Reproducibility and variability in the action of injected insulin. Diabetes Metab. 2005;31:7–13. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar A, Kalra S. Insulin initiation and intensification: insights from new studies. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59(Suppl):17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson JA. New injection recommendations for patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2010;36:S2. doi: 10.1016/S1262-3636(10)70001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frid A, Hirsch L, Gaspar R, Hicks D, Kreugel G, Liersch J, et al. New injection recommendations for patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab (French) 2010;36:S3–18. doi: 10.1016/S1262-3636(10)70002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siminerio L, Kulkarni K, Meece J, Williams A, Cypress M, Haas L, et al. Strategies of insulin injection therapy in diabetes self-management. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keininger D, Coteur G. Assessment of self-injection experience in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Psychometric validation of the Self-Injection Assessment Questionnaire (SIAQ) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:2. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kansra UC, Sircar S. Insulin therapy: Practical points. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2000;1:285–93. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okazaki K, Goto M, Yamamoto T, Tsujii S, Ishii H. Barriers and facilitators in relation to starting insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes (Abstract) Diabetes. 1999;48:A319. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Diabetes Association: Insulin administration. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:S106–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Travel and Diabetes. [Last accessed on 2012 June 28]. Available from: http://www.sweet.org.au/docs/professionals/14_Travel_and_Diabetes.pdf .

- 19.Insulin syringes. [Last accessed on 2012 May 21]. Available from: http://www.bd.com/us/diabetes/page.aspx?cat=7001andid=7251 .

- 20.Gitanjali B. A tale of too many strengths: Can we minimize prescribing errors and dispensing errors with so many formulations in the market? J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2011;2:147–9. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.83277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Syringe and pen needle sizes. [Last accessed on 2012 May 22]. Available from: http://www.bd.com/us/diabetes/page.aspx?cat=7001andid=7253 .

- 22.Holleman F, Vermeijden JW, Kuck EM, Hoekstra JB, Erkelens DW. Compatibility of insulin pens and cartridges. Lancet. 1997;350:1601–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)64018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Insulin pens. [Last accessed on 2012 May 22]. Available from: http://www.bd.com/us/diabetes/page.aspx?cat=7001andid=7254 .

- 24.Skin thickness and needle size. [Last accessed on 2012 May 22]. Available from: http://www.bd.com/us/diabetes/page.aspx?cat=7001andid=32371 .

- 25.Gibney MA, Arce CH, Byron KJ, Hirsch LJ. Skin and subcutaneous adipose layer thickness in adults with diabetes at sites used for insulin injections: Implications for needle length recommendations. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:1519–30. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.481203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo Presti D, Ingegnosi C, Strauss K. Skin and subcutaneous thickness at injecting sites in children with diabetes: ultrasound findings and recommendations for giving injection. Pediatr Diabetes. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2012.00865.x. [In Press] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yadav S. Insulin therapy. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43:863–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Injection site selection. [Last accessed on 2012 May 21]. Available from: http://www.bd.com/us/diabetes/page.aspx?cat=7001andid=7261 .

- 29.Down S, Kirkland F. Injection technique in insulin therapy. Nurs Times. 2012;108(18):20–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basi M, Hicks D, Kirkland F, Pledger J, Burmiston S. Improving diabetes injection technique. Clin Serv J. 2010 [In Press] [Google Scholar]

- 31.How to inject an insulin syringe. [Last accessed on 2012 May 22]. Available from: http://www.bd.com/us/diabetes/page.aspx?cat=7001andid=7258 .

- 32.Bohannon NJ. Insulin delivery using pen devices: simple-to-use tools may help young and old alike. Postgrad Med. 1999;106:57–68. doi: 10.3810/pgm.1999.10.15.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Czupryniak L, Drzewoski J. Insulin injection mean time interval it is NOT its length that matters. Pract Diab Int. 2001;18:338. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fowler MJ. Diabetes Treatment, Part 3: Insulin and Incretins. Clin Diabetes. 2008;26:35–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar Das A. Rapid Acting Analogues in Diabetes Mellitus Management. J Assoc Physicians India. 2009. [Last accessed on 2012 June 28]. Available from: http://www.japi.org/february_2009/rapid_acting_analogue.html .

- 36.Deckert T. Intermediate-acting Insulin Preparations: NPH and Lente. Diabetes Care. 1980;3:623–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.3.5.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Misnikova IV, Dreval AV, Gubkina VA, Rusanova EV. The risks of repeated use of insulin pen needles in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Diabetol. 2011;1:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guidelines on safe disposal of Used Needles and Syringes in the Context of Targeted Intervention for Injecting Drug Users. [Last accessed on 2012 Aug 20]. Available from: http://nacoonline.org/upload/NGO%20and%20Targeted/waste%20disposal%20guideline%20for%20IDU%20TI.pdf .

- 39.Palios J, Kadoglou NP, Lampropoulos S. The pathophysiology of HIV-/HAART-related metabolic syndrome leading to cardiovascular disorders: The emerging role of adipokines. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012:103063. doi: 10.1155/2012/103063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalra S, Unnikrishnan AG, Raza SA, Bantwal G, Baruah MP, Latt TS, et al. South Asian Consensus Guidelines for the rational management of diabetes in human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2011;15:242–50. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.85573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strauss K WISE Consensus Group. WISE recommendations to ensure the safety of injections in diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2012;38:S2–8. doi: 10.1016/S1262-3636(12)70975-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beran D. Improving access to insulin: What can be done? Diabetes Manage. 2011;1:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalra S, Kalra B. A good diabetes counselor ‘Cares’: Soft skills in diabetes counseling. Internet J Health. 2010;11:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalra S, Kalra B, Batra P. Patient Motivation for Insulin/Injectable Therapy: The Karnal Model. Int J Clin Cases Investig. 2010;1:11–5. [Google Scholar]