Abstract

Introduction:

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrinopathy of women of child-bearing age. Although some studies have suggested an association between PCOS and autoimmune thyroiditis, to our knowledge, only a few cases indicating association between PCOS and Graves’ disease are reported.

Objective:

We aim to describe this first case series of six women presenting with PCOS and Graves’ disease together.

Materials and Methods:

Women attending the endocrinology clinic at a tertiary care centre in north India and fulfilling the AE-PCOS criteria for diagnosis of PCOS were studied using a predefined proforma for any clinical, biochemical and imaging features of Graves’ disease.

Results:

The series consisted of six women with a mean age of 27.5 years and menarche as 12.6 years. All women were lean with mean BMI of 22.73 kg / m2 and three out of six had waist circumference <80 cm. The mean FG score of subjects was 16.66 and average total testosterone was 77.02 ng / dl (25.0-119.64). All the patients had suppressed TSH, the average being 0.052 μIU/ml (0.01-0.15). Thyroid gland was enlarged in all clinically and on ultrasonography and imaging with 99mTc and/or RAIU revealed diffuse increased uptake.

Conclusions:

The association of a rare disorder like Graves’ disease with a relatively common disorder like PCOS is unlikely to be because of a chance alone and may point to a common aetiopathogenic linkage leaving a scope for molecular characterization.

Keywords: Autoimmunity and hyperandrogenism, Graves’ disease, hyperthyroidism, polycystic ovary syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Graves’ disease, an autoimmune thyroid disorder predominantly occurs in women of child-bearing age. Since Graves’ thyrotoxicosis in women is frequently associated with concurrent menstrual abnormalities and marked alterations in sex hormones, it is difficult for them to conceive or to maintain pregnancy without treatment.[1] Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), the common endocrinopathy of reproductive age-group women, is a frequent cause of menstrual abnormalities, anovulation, infertility, hyperandrogenism, visceral obesity, and insulin resistance in these women.[2–5] Although, overt hypothyroidism is known to produce a reversible phenotype similar to that of PCOS, there are no reports of association of hyperthyroidism with PCOS. We previously reported association of subclinical hypothyroidism in the full blown cases of PCOS and it did not seem to change any clinical, biochemical or hormonal picture in these subjects.[6] This very finding may suggest an alternative reason than the hormonal perturbations to explain the link. Autoimmunity can be one of the possible mechanisms to explain the association between these two diverse disorders. Only few studies are reported suggesting a relationship between autoimmune diseases including Hashimoto's thyroiditis and PCOS.[7–11] Our earlier observation of a very high prevalence of PCOS phenotype in clinically, biochemically, radiologically and serologically proven chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (CLT) in young and adolescent women supports this concept.[12]

Here, we report six young and adolescent women who qualified the diagnosis of PCOS and had active Graves’ disease at the time of PCOS diagnosis. There is no data on association of Graves’ disease and PCOS except one case record[13] and hence this is the first case series in the literature, to the best of our knowledge. The presentation may pave the way for further research to understand any possible link between PCOS and Graves’ disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Over the last five years, six women with Graves’ disease were diagnosed in a cohort of young women with PCOS diagnosed on the basis of AE-PCOS criteria of 2006.[14] These women presented with menstrual irregularity, infertility or history of it, and features of hyperandrogenism to the Endocrinology clinic of a 650-bed tertiary care hospital in the Kashmir valley of North India, which approximately caters to a population of 5.6 million. PCOS was defined as chronic amenorrhea (no cycles in the past six months) or oligomenorrhea (cycles lasting longer than 35 days or a total of <8 menses per year), clinical or laboratory hyperandrogenism and the absence of any adrenal or pituitary disorder. Clinical hyperandrogenism was defined as hirsutism (Modified Ferriman–Gallwey score >8) and or severe acne, and/or androgenic pattern of alopecia.[15] Biochemical hyperandrogenemia was defined by elevated testosterone (>65.0 ng/dl). A luteinizing hormone (LH)-to-follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) ratio above two was considered elevated. USG abdomen was done to study polycystic ovarian morphology and to rule out any adrenal or ovarian mass lesion. The diagnosis of PCOS on trans-abdominal USG was based on the presence of: >12 peripheral follicles each 2-9mm in diameter in one or both ovaries, increased ovarian volume (>10 cmm) on one or both sides and thecal hyperechogenecity in the mid follicular phase.[16] Other reasons for hyperandrogenism were excluded by adrenocorticotropin-stimulated 17- OH progesterone and, if hypercortisolism was clinically suspected, by dexamethasone suppression test. Graves’ disease was diagnosed by clinical features, biochemical evidence and thyroid scan or radio-iodine uptake. Clinical examination included anthropometric assessment; in addition to routine systemic examination. An informed consent was obtained from the patients and their spouses. The study was approved by the Institute's ethics committee.

Investigations

Baseline serum samples were taken in all women in a fasting state for glucose, lipids, in addition to hormonal profile including T3, T4, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), cortisol (morning), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), prolactin (PRL), 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP), and total testosterone (T). The samples for LH, FSH, T, and 17-OHP were collected on days 3–7 (early follicular phase) of spontaneous cycle or medroxyprogesterone-induced menstrual cycle in amenorrheic patients. Overnight dexamethasone suppression test, if needed, was done after taking basal samples and performing OGTT.

Hormonal analysis for serum LH, FSH, total testosterone, prolactin, 17-OH progesterone (17OHP), serum cortisol (8 AM); TSH, total T4 and total T3 was performed using standardized methods . Other investigations included lipid profile, OGTT for insulin and glucose, liver function tests, renal function tests, and serum uric acid.

Assays

Radioimmunoassay (RIA) was used to analyze T3, T4, cortisol, 17-OHP, T and immunoradiometric assay (IRMA) was used to analyze TSH, LH, FSH,PRL using commercial kits in duplicate and according to supplier protocol (Shin Jin Medics Inc., Gyeonggi-do, Korea, for TSH; Immunotech, Marseille Cedex 9, France, for T, 17-OHP, cortisol, PRL, LH, and FSH). Plasma glucose (mg/dl) was measured by glucose oxidase peroxidase (GOD-POD) method on Hitachi 912, Japan. Intra and inter-assay variations were within the limits permitted by the manufacturer.

RESULTS

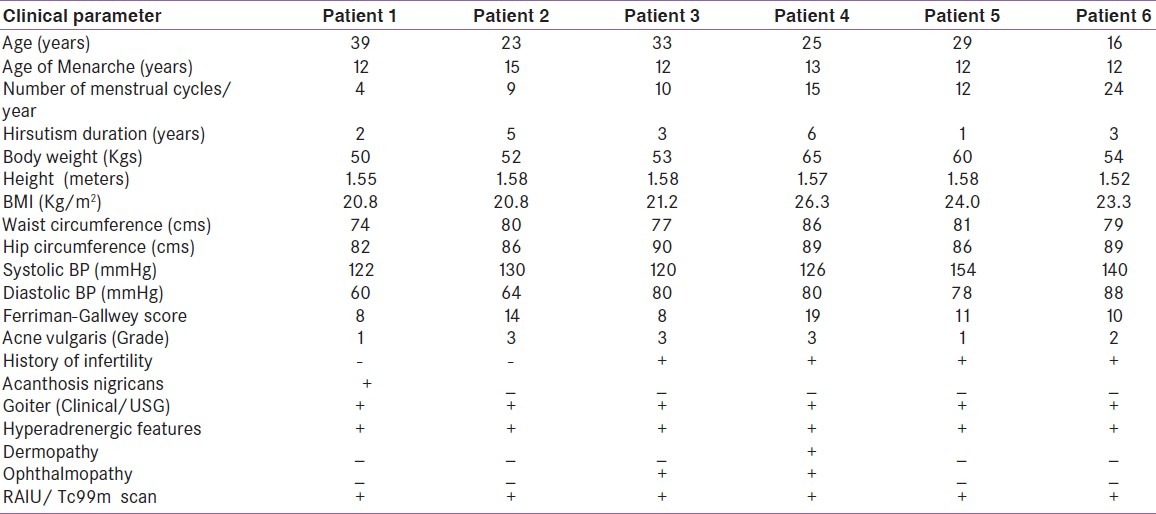

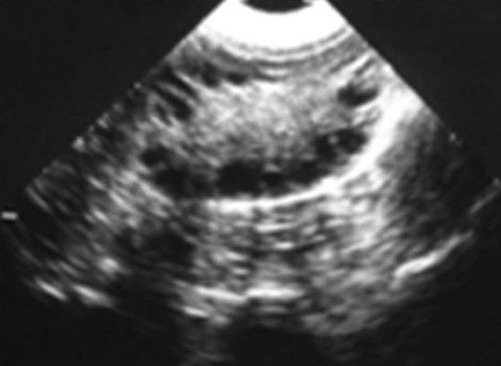

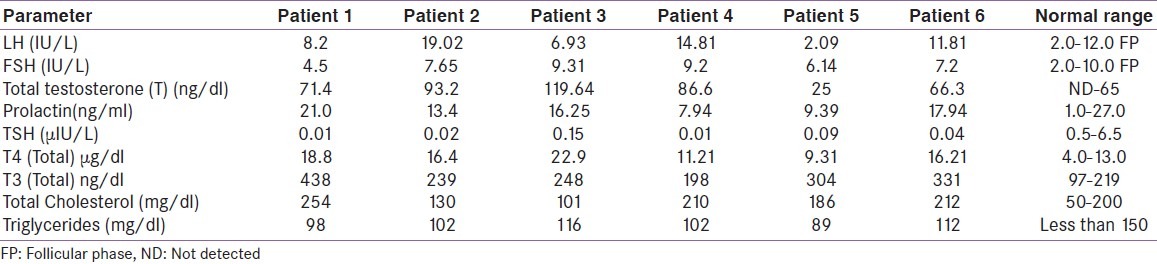

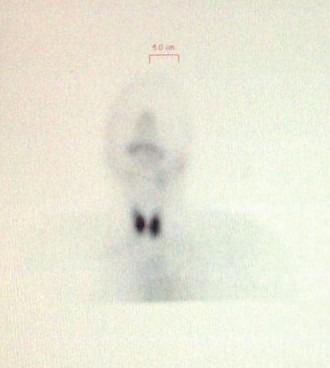

The series consisting of six women with confirmed diagnosis of PCOS presented with clinical features of active Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Mean age of the subjects at the time of diagnoses was 27.5 years (16–39 years) with mean age of menarche as 12.6 years (range 12- 15 years). All these women were lean with the average BMI was 22.73 kg/ m2 ranging from 21.2 to 26.3 and waist circumference of less than 80 cm in three of them (mean waist circumference as 79.5 cm). Five out of six cases had history of sub-fertility and was restored after ovulation induction by clomiphene in three (3/5, 60%) subjects. All these women had hirsuitism, moderate to severe acne vulgaris [Figure 1a] and three (50%) had androgenic alopecia. The mean hirsuitism score was 16.66. One out of six (16.6%) patients had acanthosis nigricans at presentation [Table 1]. The transabdominal USG was suggestive of PCOS in all the six women [Figure 1b]. The mean LH and FSH was 17.96 IU/L (2.09-19.02) and 7.33 IU/L (4.5-9.31) respectively with three out of six patients (50%) having LH/FSH ratio of more than 2. Mean serum total testosterone was 77.02 ng/dl (25.0-119.64) with 4/6 qualifying for biochemical hyperandrogenism [Table 2]. All women had clinical features of Graves’ hyperthyroidism in the form of hyperadrenergic state and diffuse soft goiter [Table 1]. Mechanical ophthalmopathy was evident in two women and dermopathy affected only one. Thyroid gland was enlarged in all the patients on ultrasonography and 99mTc and/or RAIU revealed increased uptake [Figure 1c]. Thyroid function test suggested suppressed TSH (the average 0.052μIU/ml with range 0.01-0.15) and elevated total T4 (mean 15.8μg/dl) and T3 [Table 2].

Figure 1a.

Showing facial hair growth, acne vulgaris, hyperhidrosis, acanthosis nigricans and diffuse goiter (patient #3)

Table 1.

Description of clinical features of the cases in our series

Figure 1b.

Showing thyroid USG showing increases size of the gland with increases echogenecity

Table 2.

Showing biochemical and hormonal workup of the cases

Figure 1c.

Showing increased tracer uptake with Tc99m after 20 minutes after IV contrast in patient #2

DISCUSSION

Among the cohort of PCOS women following our clinic, we encountered six women who also had features suggestive of Graves’ disease. These patients had oligomenorrhea, hirsutism, elevated levels of androgens, long-term anovulation and polycystic ovaries on USG,[16,17] and thereby fulfilling AE-PCOS criteria for the diagnosis of PCOS.[14] The incidence of PCOS in premenopausal women (20- 40 years) is reported to be 5-10% and PCOS being a major cause of infertility, assumes significance in women reproductive health.[18] High percentages (50-70%) of PCOS women display resistance and central obesity. This deterioration of insulin sensitivity, resulting from increased insulin resistance or hyperinsulinemia, suppresses the synthesis of SHBG in the liver, leading to increased ovarian or adrenal androgen production. How hyperinsulinemia or insulin resistance influences the synthesis of steroids at the cellular level is not clearly elucidated. However, insulin resistance is not universal in PCOS subjects, as some authors[19] reported that a considerable portion of women with PCOS have insulin sensitivity comparable to that of healthy controls. To support this hypothesis, some previous reports suggest that thin PCOS women respond poorly to metformin.[20,21] Together these observations suggest that the mechanisms other than insulin resistance may be involved in PCOS pathogenesis. Autoimmune diseases are sometimes associated with premature ovarian failure or infertility and antibodies for steroid hormone-producing tissues (ovary or adrenal) or specific enzymes involved in steroid metabolism have been demonstrated. Nonetheless, it is still controversial whether autoimmunity is primarily induced during the development of PCOS. In some PCOS women, a high concentration of antibodies against ovarian tissue, antinuclear antibodies and anti-smooth muscle cell antibodies have been reported.[11] Hashimoto's thyroiditis, a common autoimmune disease affecting thyroid gland has been shown to have association with PCOS.[7–9] In a recent study by Janssen et al,[24] on 175 PCOS and 168 normal women, anti-thyroid antibodies were detected at a high rate in the PCOS group compared to the control group (27% versus 8.3%). A high percentage of the PCOS group showed a typical low echo ultrasonographic finding observed in thyroiditis compared to controls (42.3% versus 6.5%). In addition, a high concentration of serum TSH concentration was detected in the PCOS group.[24] They postulated that because of long-term anovulation in PCOS patients, the reduced level of serum progesterone and relatively elevated estrogen levels accelerate the autoimmune response, eventually leading to increased chance of Hashimoto's thyroiditis. In addition, this consequent hypothyroidism, even mild, may induce a vicious deterioration of PCOS by enhancing conversion of androstenedione to testosterone or estradiol, and decreasing metabolism of sex hormones.[25] Since PCOS and autoimmune thyroiditis show familial clustering, a common genetic pathway could be an alternative explanation.

Like Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Graves’ disease falls in the spectrum of thyroid associated autoimmunity and can develop within families or in an individual at different times.[26] Thyrotoxicosis induced by Graves’ disease is known to be associated with menstrual abnormalities though, ovulation normally occurs in most patients. The elevated SHBG, increased estradiol, testosterone and androstenedione incriminated in these abnormalities,[23–26] eventually reverse with normalization of the thyroid functions. Considering the frequent co-occurrence of Hashimoto's thyroiditis in women with PCOS, as shown in previous clinical studies,[7–9,20] the very rare combination of PCOS and Graves’ disease among young women is rare and seems interesting. Janssen et al, reported that the incidence of chronic autoimmune thyroiditis was 23.9% (47/175) in patients with PCOS, and they also described two subjects with Graves’ disease in their PCOS group.[20] The present case series of women with definite PCOS (AE-PCOS criteria) had evidence of Graves’ disease on clinical, biochemical and imaging grounds. The PCOS features such as hirsuitism, elevated serum testosterone were too overt to account for abnormalities secondary to Graves’ disease. Furthermore, when these patients achieved euthyroidism, PCOS features did not change for several months after anti-thyroid drug use. The coincidence of PCOS and thyroiditis/Graves’ disease in these women may emphasize the role of autoimmunity in the development of PCOS. The limited number of reports describing the combination of PCOS and Graves’ disease can be attributed to poor reporting.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case series of women with PCOS who had coexisting Graves’ disease in active form. PCOS being a relatively common condition as compared to Grave's disease which is relatively rare in our population. The the major limitation of our study is that it is a mere observation in a cross sectional setting of two conditions rather than a prospective follow up recording the preceding events. Whether their coexistence is a chance finding or has any pathogenic relevance, remains contentious at present. In line with the recent publications about the associations of autoimmunity and PCOS, this co-occurrence may have pathological significance and pave the way for future studies to unravel role of autoimmunity in women with PCOS. Therefore, there is need of well designed prospective longitudinal studies with both clinical and molecular workup to unravel the association noted by us. Furthermore, clinicians should rule out PCOS in Graves’ hyperthyroidism women persisting with reproductive abnormalities after achieving euthyroidism.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koutras DA. Disturbances of menstruation in thyroid disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;816:280–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franks S. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:853–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509283331307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehrmann DA. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1223–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norman RJ, Dewailly D, Legro RS, Hickey TE. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet. 2007;370:685–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Homburg R. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22:261–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganie MA, Laway BA, Wani TA, Zargar MA, Nisar S, Ahamed F, et al. Association of subclinical hypothyroidism and phenotype, insulin resistance, and lipid parameters in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2039–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuoka LY, Wortsman J, Gavin JR, 3rd, Kupchella CE, Dietrich JG. Acanthosis nigricans, hypothyroidism, and insulin resistance. Am J Med. 1986;81:58–62. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goi R, Matsuda M, Maekawa H, Ogawa T, Sakata S. Two cases of Hashimoto's thyroiditis with transient hypothyroidism. Intern Med. 1992;31:64–8. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.31.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sridhar GR, Nagamani G. Hypothyroidism presenting with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Assoc Physicians India. 1993;41:88–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SH, Kim MR, Kim JH, Kwon HS, Yoon KH, Son HY, et al. A patient with combined polycystic ovary syndrome and autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23:252–6. doi: 10.1080/09513590701297658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reimand K, Talja I, Metskula K, Kadastik U, Matt K, Uibo R. Autoantibody studies of female patients with reproductive failure. J Reprod Immunol. 2001;51:167–76. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(01)00075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganie MA, Marwaha RK, Aggarwal R, Singh S. High prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome characteristics in girls with euthyroid chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis: A case-control study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:1117–22. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung JH, Hahm JR, Jung TS, Kim HJ, Kim HS, Kim S, et al. A 27-year-old woman diagnosed as polycystic ovary syndrome associated with Graves’ disease. Intern Med. 2011;50:2185–9. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.5475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Escobar-Morreale HF, Futterweit W, et al. Task Force on the Phenotype of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome of The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:456–88. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferriman D, Gallwey JD. Clinical assessment of body hair growth in women. J Clin Endo Metab. 1961;21:1440–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem-21-11-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox R, Hull M. Ultrasound diagnosis of polycystic ovaries. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1993;687:217–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb43868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Hum Reprod. 2004;19:41–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hull MG. Epidemiology of infertility and polycystic ovarian disease: Endocrinological and demographic studies. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1987;1:235–45. doi: 10.3109/09513598709023610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cibula D. Is insulin resistance an essential component of PCOS.: The influence of confounding factors? Hum Reprod. 2004;19:757–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trolle B, Flyvbjerg A, Kesmodel U, Lauszus FF. Efficacy of metformin in obese and non-obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover trial. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2967–73. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahin Y, Unluhizarci K, Yilmazsoy A, Yikilmaz A, Aygen E, Kelestimur F. The effects of metformin on metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors in nonobese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;67:904–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee S, Choi S, Kim HJ, Chung YS, Lee KW, Lee HC, et al. Cutoff values of surrogate measures of insulin resistance for metabolic syndrome in Korean nondiabetic adults. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:695–700. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.4.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeni-Komshian H, Carantoni M, Abbasi F, Reaven GM. Relationship between several surrogate estimates of insulin resistance and quantification of insulin-mediated glucose disposal in 490 healthy nondiabetic volunteers. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:171–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssen OE, Mehlmauer N, Hahn S, Offner AH, Gartner R. High prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150:363–9. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1500363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghosh S, Kabir S, Pakrashi A, Chatterjee S, Chakravarty B. Subclinical hypothyroidism: A determinant of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hormone Res. 1993;39:61–6. doi: 10.1159/000182697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takasu N, Yamada T, Sato A, Nakagawa M, Komiya I, Nagasawa Y, et al. Graves’ disease following hypothyroidism due to Hashimoto's disease: studies of eight cases. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1990;33:687–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1990.tb03906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]