Abstract

Different approaches were utilized to investigate the mechanism by which fusicoccin (FC) induces the activation of the H+-ATPase in plasma membrane (PM) isolated from radish (Raphanus sativus L.) seedlings treated in vivo with (FC-PM) or without (C-PM) FC. Treatment of FC-PM with different detergents indicated that PM H+-ATPase and the FC-FC-binding-protein (FCBP) complex were solubilized to a similar extent. Fractionation of solubilized FC-PM proteins by a linear sucrose-density gradient showed that the two proteins comigrated and that PM H+-ATPase retained the activated state induced by FC. Solubilized PM proteins were also fractionated by a fast-protein liquid chromatography anion-exchange column. Comparison between C-PM and FC-PM indicated that in vivo treatment of the seedlings with FC caused different elution profiles; PM H+-ATPase from FC-PM was only partially separated from the FC-FCBP complex and eluted at a higher NaCl concentration than did PM H+-ATPase from C-PM. Western analysis of fast-protein liquid chromatography fractions probed with an anti-N terminus PM H+-ATPase antiserum and with an anti-14–3-3 antiserum indicated an FC-induced association of FCBP with the PM H+-ATPase. Analysis of the activation state of PM H+-ATPase in fractions in which the enzyme was partially separated from FCBP suggested that the establishment of an association between the two proteins was necessary to maintain the FC-induced activation of the enzyme.

The phytoxin FC is a powerful effector of the PM H+-ATPase and has been widely used as a tool with which to study the mechanism of physiological modulation of this crucial enzyme (Marrè, 1979; Marrè et al., 1993).

A high-affinity FCBP has been identified from different plant tissues (Aducci and Ballio, 1989; Weiler et al., 1990), and highly purified FCBP preparations have been obtained from several plant materials (de Boer et al., 1989; Oecking and Weiler, 1991; Aducci et al., 1993; Korthout et al., 1994). Work on isolated PM vesicles and on proteoliposomes reconstituted with partially purified PM H+-ATPase and FCBP has shown that FC, upon binding to PM-localized FCBP, causes strong activation of the PM H+-ATPase (for review, see Aducci et al., 1995). Stimulation of the PM H+-ATPase is variable and erratic when FC is added to isolated PM, whereas it becomes more dramatic when FC is fed in vivo. This activation determines a shift in the pH optimum of the enzyme toward more alkaline values and a decrease in the apparent Km for the substrate Mg-ATP (Rasi-Caldogno and Pugliarello, 1985; Rasi-Caldogno et al., 1986, 1993; De Michelis et al., 1991; Johansson et al., 1993; Olivari et al., 1993; Lanfermeijer and Prins, 1994).

The PM H+-ATPase has a C-terminal autoinhibitory domain (Palmgren et al., 1990, 1991), and biochemical analysis of FC- and trypsin-treated PM (the latter treatment resulting in the loss of the C-terminal tail) has shown that FC-induced activation of PM H+-ATPase depends on a conformational modification of the enzyme, leading to the displacement of the C terminus (De Michelis et al., 1992; Rasi-Caldogno et al., 1993; Johansson et al., 1993; Lanfermeijer and Prins, 1994).

The FCBP is a member of the 14–3-3 protein family (Korthout and de Boer, 1994; Marra et al., 1994; Oecking et al., 1994), highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed proteins that bind to a variety of proteins involved in signal transduction and cell cycle regulation (Aitken et al., 1992; Morrison, 1994). We recently compared the maximum FC-binding capacity and the amount of H+-ATPase in PM isolated from Arabidopsis thaliana and radish (Raphanus sativus L.) seedlings, and found evidence to suggest a one-to-one stoichiometry between the FCBP and PM H+-ATPase (De Michelis et al., 1996b), indicating that there is no amplification step between the signal perceived by the FCBP and the activation of the PM H+-ATPase. This suggests that the FC-induced activation of the PM H+-ATPase depends on the molecular interaction of the FC-FCBP complex with the enzyme.

These data are consistent with the hypothesis that FC-induced activation of PM H+-ATPase depends on a direct interaction of the FC-FCBP complex with the enzyme, leading to the displacement of the C-terminal autoinhibitory domain.

Marra et al. (1996) showed that solubilized PM H+-ATPase from maize roots treated in vivo with FC and fractionated by anion-exchange HPLC eluted separately with respect to FCBP and retained its activated state after enzyme insertion into liposomes, thus suggesting a permanent modification of the PM H+-ATPase not dependent on a direct interaction of the FC-FCBP complex with the enzyme.

In this work we applied different approaches (solubilization with different detergents and Suc-density gradient and anion-exchange FPLC) to separate the PM H+-ATPase in the PM fraction purified from radish seedlings treated in vivo with or without FC from the FC-FCBP and to then analyze the activation state of the enzyme. The results obtained show that FC binding to FCBP induces an interaction between the PM H+-ATPase and the FC-FCBP complex and suggest that such an interaction is necessary to activate the PM H+-ATPase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Germination of Seeds and Isolation of PM

The method for germination of radish (Raphanus sativus L. cv Tondo Rosso Quarantino; Ingegnoli, Milan, Italy) seeds was published previously (De Michelis et al., 1996b). FC treatment was performed after 21 h of seedling germination by the addition of 5 μm FC for 3 h, after which seedlings were frozen at −80°C. A PM-enriched fraction was obtained by an aqueous two-phase partitioning system, as described previously (Rasi-Caldogno et al., 1995). Membrane proteins were assayed according to the method of Markwell et al. (1978).

Solubilization of PM H+-ATPase and the FC-FCBP Complex

To solubilize PM H+-ATPase and FC-FCBP, PM was incubated with different detergent concentrations (specified in the figure legends) for 15 min on ice in the presence of 10% (v/v) glycerol, 20 mm Mops-KOH, pH 7.0, 1 mm p-aminobenzamidine, 0.1 mm PMSF, 2 mm DTT, 1 mm ATP, 0.2 mm EDTA, and 0.25 m KBr and then centrifuged for 45 min at 60,000g. SN was collected and the pellet was resuspended with 1 mm Mops-KOH, pH 7.0, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.5 mm DTT.

Separation of Solubilized PM Proteins by Linear Suc Gradient

Proteins solubilized with dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (3 mg protein mL−1:3 mg detergent mL−1) were fractionated by a linear Suc-density gradient (5–38%, w/w). The gradient was prepared using two initial solutions containing 10 mm Mops-KOH, pH 7.0, 1 mm DTT, 100 μg mL−1 polyoxyethylene 20 cetyl ether, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 5 or 38% (w/w) Suc. At the bottom of the gradient, 2 mL of 50% Suc solution with the same composition as the gradient solution without glycerol was set. Two milliliters of SN from the solubilization procedure was layered on the top of the gradient, which was centrifuged for 16 h at 265,000g. At the end of the run, 1-mL fractions were collected from the top of the gradient and frozen at −80°C until use.

Anion-Exchange FPLC

C-PM and FC-PM were diluted to 2 mg mL−1 protein in 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 15% (v/v) glycerol, 0.75 mm DTT, 2 mm EDTA, and 0.1 mm PMSF, treated with 3.7 mg mL−1 Triton X-100 and 0.5 m KCl, kept on ice for 4 min, and then centrifuged at 60,000g for 45 min. The pellet was resuspended at 4 mg mL−1 protein in 10 mm Mops-bis-Tris propane (1,3-bis[Tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propane), pH 7.0, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mm EDTA, 0.1 DTT, 0.5 mm ATP, and 0.1 mm PMSF and then diluted to 2 mg mL−1 protein with an equal volume of the same solution containing 20 mg mL−1 dodecyl-β-d-maltoside. After 30 min at room temperature, samples were centrifuged at 60,000g for 45 min and the SN was loaded onto an FPLC Mono-Q HR 5/5 anion-exchange column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 20 mm l-His, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm DTT, 0.5 mm ATP, and 0.5 mg mL−1 dodecyl-β-d-maltoside, pH 6.5. Elution was performed by FPLC (Pharmacia) with a linear NaCl gradient (0–0.6 m NaCl in 24 mL; flow rate, 0.7 mL min−1) in the same buffer utilized to equilibrate the column, and 0.7-mL fractions were collected and frozen at −80°C until use.

PM H+-ATPase Activity

Vanadate-sensitive PM H+-ATPase activity was assayed at pH 7.5 and 6.4 at 30°C, as described by Rasi-Caldogno et al. (1993).

Treatment with asolectin was performed by incubation of samples diluted 1:1 with a sonicated solution containing 15 mg mL−1 asolectin, 10 mm Mops-bis-Tris propane, pH 7.0, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mm EDTA, and 9.375 mg mL−1 dodecyl-β-d-maltoside for 8 min at room temperature (keeping constant the ratio between asolectin and dodecyl-β-d-maltoside). The standard assay medium was then added. The concentration of asolectin used during the assay was 300 μg mL−1.

FC RIA

Antiserum against BSA-conjugated dideacetyl-FC was kindly supplied by P. Aducci and M. Marra (Dipartimento di Biologia, Università di Roma Tor Vergata, Italy). [3H]FC (0.7 kBq pmol−1) was a generous gift of Professor G. Randazzo (Università di Napoli, Italy). FC RIA was performed as described previously (De Michelis et al., 1996b).

SDS-PAGE

SDS-PAGE was performed essentially according to the method of Laemmli (1970). Samples were treated as reported by Rasi-Caldogno et al. (1993). About 2 to 5 μg of proteins from the FPLC fractions per lane was loaded onto a 4 to 20% gradient polyacrylamide Tris-Gly minigel (catalog no. 161-0903, Bio-Rad) and subjected to electrophoresis under standard conditions.

Western Analysis

After SDS-PAGE the polypeptides were electrophoretically transferred to a 0.2-μm cellulosenitrate membrane (reference no. 401–391, Schleicher & Schuell) and incubated for 2 h with anti-N-terminus H+-ATPase polyclonal antibody (diluted 1:1000) or with anti-14–3-3 polyclonal antibody (diluted 1:6000), kindly supplied by P. Aducci and M. Marra. Immunodecoration was performed in both cases with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (catalog no. 170-6463, Bio-Rad). The PM H+-ATPase was detected with an immunoblot assay kit (catalog no. 170-6463, Bio-Rad). The 14–3-3 protein was detected with the enhanced chemiluminescence system (RPN 2209, Amersham). The antiserum against the N-terminal domain of the PM H+-ATPase was obtained by inoculating a rabbit with a synthetic peptide corresponding to a highly conserved sequence (amino acids 10–24) of isoform 2 of Arabidopsis thaliana PM H+-ATPase (Harper et al., 1990), which was conjugated with ovalbumin. The antiserum was saturated overnight with 1% ovalbumin and partially purified by (NH4)2SO4 fractionation; the fraction precipitated between 33 and 50% (NH4)2SO4 was suspended in TBS, aliquoted, and stored at −20°C.

Statistics

Data are from one experiment representative of at least three experiments performed on independent PM preparations. All assays were run with three replicates.

RESULTS

Solubilization of PM H+-ATPase and the FC-FCBP Complex

In the first set of experiments we compared the efficiency of different detergents to solubilize the PM H+-ATPase and the FC-FCBP. Table I shows the PM H+-ATPase activity measured in PM purified from untreated radish seedlings (C-PM) and in the SN and pellet obtained after solubilization with n-octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside and dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (nonionic detergents) or Chaps (a zwitterionic detergent) at different ratios of protein to detergent. Different detergents solubilized the PM H+-ATPase to different extents. Solubilization of C-PM (1 mg protein mL−1) with n-octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (4–8 mg mL−1) determined a low recovery of PM H+-ATPase activity in the SN fraction and a slight inhibition of total activity, whereas increasing the concentration up to 16 mg mL−1 led to an almost complete loss of PM H+-ATPase activity, both in the pellet and in the SN. Chaps (16 mg mL−1 with 1 mg protein mL−1) caused a slight inhibition of PM H+-ATPase activity and a low recovery in the SN. Among the detergents tested, dodecyl-β-d-maltoside was the only one that solubilized the PM H+-ATPase with good yield: about 80% of the activity was recovered in the SN when a 1:1 ratio of protein to detergent was used, without significant effect on the activity of the PM H+-ATPase.

Table I.

Solubilization of the PM H+-ATPase from C-PM with different detergents

| Detergent | Protein:Detergent | PM

H+-ATPase

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Pellet | SN | ||

| mg mL−1:mg mL−1 | nmol Pi min−1 | |||

| n-Octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside | 1:4 | 300 | 225 | 85 |

| 1:8 | 310 | 148 | 122 | |

| 1:16 | 316 | 0 | 40 | |

| Chaps | 1:16 | 288 | 114 | 123 |

| Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside | 1:0.5 | 291 | 242 | n.d.a |

| 1:1 | 280 | 71 | 265 | |

| 3:3 | 271 | 50 | 236 | |

C-PM protein (1 mg) was solubilized with the specified detergent, as described in Methods. PM H+-ATPase activity was measured at pH 6.4.

n.d., Not determined.

To compare the efficiency of different detergents to solubilize the PM H+-ATPase and the FC-FCBP complex, we evaluated the PM H+-ATPase activity and the amount of FC-FCBP complex in the pellet obtained after solubilization of PM purified from FC-treated seedlings (FC-PM) in different conditions. Evaluation of the FC-FCBP complex in the SN was not possible because of interference of detergents with the FC RIA (data not shown). Table II shows PM H+-ATPase activity and the FC-FCBP complex measured in the insoluble fraction after solubilization of FC-PM with n-octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside, Chaps, and dodecyl-β-d-maltoside. In agreement with the data shown in Table I, the detergents solubilized the PM H+-ATPase to different extents. The same pattern was obtained when the concentration of the FC-FCBP complex was evaluated; in all of the detergents tested, the percentage of the two proteins remaining in the pellet after solubilization was similar.

Table II.

Solubilization of the PM H+-ATPase and of the FC-FCBP complex from FC-PM with different detergents

| Protein:Detergent | PM H+-ATPase | FC-FCBP |

|---|---|---|

| mg mL−1:mg mL−1 | nmol Pi min−1 | pmol |

| Native PM | 387 (100%) | 33.75 (100%) |

| n-Octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (1:8) | 185 (48%) | 16.87 (50%) |

| Chaps (1:16) | 205 (53%) | 22.50 (67%) |

| Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (1:1) | 120 (31%) | 11.13 (33%) |

FC-PM protein (1 mg) was solubilized with the specified detergents, as described in Methods. PM H+-ATPase activity was assayed in the pellet at pH 6.4. FC-FCBP was measured in the pellet by FC RIA.

In native PM vesicles, FC-induced activation of PM H+-ATPase is much stronger at pH values typical of the cytoplasm of a plant cell (pH 7.5) than at the relatively acidic pH optimum of the enzyme; therefore, the ratio between the activity measured at pH 6.4 and that measured at pH 7.5 (the pH ratio) is lower in FC-PM compared with that measured in C-PM (Rasi-Caldogno and Pugliarello, 1985; Rasi-Caldogno et al., 1986, 1993; Schulz et al., 1990; De Michelis et al., 1991; Olivari et al., 1993; Johansson et al., 1993). The pH ratio is therefore a useful parameter to monitor the activation state of the PM H+-ATPase. Table III shows the PM H+-ATPase activity measured at pH 6.4 and 7.5 and the corresponding pH ratios in native PM and the SN after solubilization of C-PM and FC-PM with different detergents. All detergents increased the pH ratio of solubilized PM H+-ATPase with respect to that measured in native PM. However, in all conditions tested the pH ratio in the SN fraction from FC-PM was one-half that from C-PM, indicating that the enzyme solubilized from FC-PM maintained its activated state.

Table III.

pH ratios of the PM H+-ATPase activity solubilized from C-PM and FC-PM

| Protein:Detergent | PM H+-ATPase

Activity

|

pH Ratio

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH

6.4

|

pH 7.5

|

C-PM | FC-PM | |||

| C-PM | FC-PM | C-PM | FC-PM | |||

| mg mL−1:mg mL−1 | nmol Pi min−1 | |||||

| Native PM | 306 | 370 | 87 | 205 | 3.5 | 1.8 |

| Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (1:1) | 186 | 285 | 25 | 81 | 7.4 | 3.5 |

| Chaps (1:16) | 91 | 128 | 8.4 | 27 | 10.8 | 4.7 |

FC-PM protein (1 mg) was solubilized with the specified detergents, as described in Methods. The pH ratio is the ratio between the activity measured at pH 6.4 and that measured at pH 7.5.

In PM vesicles isolated from different plant materials, lysoPC activates the PM H+-ATPase (Palmgren et al., 1991; Rasi-Caldogno et al., 1993; Lanfermeijer and Prins, 1994; De Michelis et al., 1996a). The biochemical characteristics of such an activation are quantitatively and qualitatively similar to those induced by proteolytic treatment of the PM H+-ATPase (Palmgren et al., 1990, 1991; Johansson et al., 1993; Rasi-Caldogno et al., 1993). C-terminal deletion analysis of PM H+-ATPase expressed in yeast indicated that at least 38 C-terminal residues are necessary to determine lysoPC-induced activation of the PM H+-ATPase (Regenberg et al., 1995). Accordingly, in native PM, activation of PM H+-ATPase by FC and lysoPC are not additive, suggesting an at least partially common mechanism involving the displacement of the C-terminal inhibitory domain (Johansson et al., 1993; Rasi-Caldogno et al., 1993; De Michelis et al., 1996a).

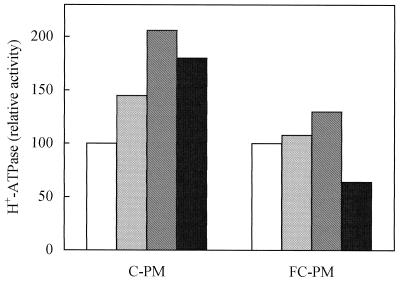

We tested the effect of lysoPC on the PM H+-ATPase solubilized from C-PM and FC-PM. Figure 1 shows the PM H+-ATPase activity measured at pH 7.5 in the SN obtained after solubilization of C-PM and FC-PM with dodecyl-β-d-maltoside in the presence of different concentrations of lysoPC. The PM H+-ATPase activity solubilized from C-PM was stimulated by lysoPC in a concentration-dependent manner: stimulation increased up to 20 μg mL−1 (106%) and slightly decreased upon further increase of lysoPC concentration. When SN from FC-PM was analyzed, the PM H+-ATPase activity was only scarcely stimulated (27%) by 20 μg mL−1 lysoPC and was severely inhibited by higher concentrations of lysoPC, thus confirming that the H+-ATPase solubilized from FC-PM retains its activated state.

Figure 1.

Effect of lysoPC on C-PM and FC-PM H+-ATPase activity solubilized with dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (1 mg protein mL−1:1 mg detergent mL−1). The assay was performed at pH 7.5 and lysoPC was added to the assay medium at 10 μg mL−1 (light gray bar), 20 μg mL−1 (gray bar), or 40 μg mL−1 (black bar). PM H+-ATPase activity is expressed as a percentage of that measured in the absence of lysoPC (open bars): 29 nmol Pi min−1 mg−1 for C-PM and 67 nmol Pi min−1 mg−1 for FC-PM.

Fractionation of Solubilized PM Proteins by Suc-Density Gradient and Anion-Exchange FPLC

Data shown in the previous section indicate that the PM H+-ATPase from FC-PM maintains its activated state upon solubilization. Since the detergents tested solubilized the PM H+-ATPase and the FC-FCBP complex to a similar extent, these data are in agreement with two hypotheses: (a) that the two proteins interact strictly (directly or via other partner proteins) and this interaction is the basis of FC-induced activation of the PM H+-ATPase; and (b) that the simultaneous presence of PM H+-ATPase and the FC-FCBP complex in the SN is simply due to a random distribution of the two proteins between SN and pelletable fractions but is not required for PM H+-ATPase activation.

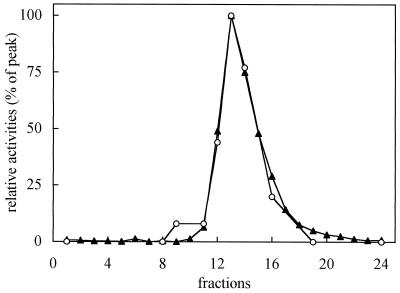

To discriminate between the two hypotheses we fractionated the SN from FC-PM obtained after solubilization with dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (3 mg proteins mL−1:3 mg detergent mL−1) by a linear Suc gradient (5–38% [w/w]). Figure 2 shows the distribution profile of the PM H+-ATPase activity and of the FC-FCBP complex: the two proteins comigrated, forming a sharp peak at fraction 13 (corresponding to 26% [w/w] Suc). The profile of the PM Ca2+-ATPase analyzed in the same gradient was clearly separated (data not shown). We also fractionated the SN from C-PM after solubilization in the same conditions and compared the pH ratios of the PM H+-ATPase activity in the peak gradient fractions from C-PM and FC-PM. Table IV shows the PM H+-ATPase activities at pH 6.4 and 7.5 and the pH ratios measured in the solubilized PM before fractionation and in three peak gradient fractions: although the pH ratio increased after fractionation, in the fractions from FC-PM this ratio was always much lower than that measured in the fractions from C-PM, indicating that after Suc-gradient fractionation the PM H+-ATPase from FC-PM maintained its activated state.

Figure 2.

Distribution profiles of PM H+-ATPase activity (▴) and the FC-FCBP complex (○) after solubilization of 6 mg of FC-PM proteins with dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (3 mg protein mL−1:3 mg detergent mL−1) and fractionation by a linear Suc-density gradient (5–38% [w/w]). PM H+-ATPase activity was measured at pH 6.4 in the presence of 10% glycerol (v/v). The FC-FCBP complex was assayed as FC RIA (see Methods). PM H+-ATPase activity and amount of FC-FCBP are expressed as percentages of the peak fraction (822 nmol Pi min−1 and 150 pmol bound FC, respectively).

Table IV.

pH ratio of PM H+-ATPase activity in Suc-density gradient peak fractions from C-PM and FC-PM

| Fraction | PM H+-ATPase

Activity

|

pH Ratio

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH

6.4

|

pH 7.5

|

C-PM | FC-PM | |||

| C-PM | FC-PM | C-PM | FC-PM | |||

| nmol Pi min−1 | ||||||

| Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside SN | 1608 | 2202 | 324 | 1200 | 5 | 1.8 |

| Fraction 12 | 510 | 402 | 36 | 102 | 14.2 | 4 |

| Fraction 13 | 468 | 822 | 30 | 282 | 15.6 | 2.9 |

| Fraction 14 | 276 | 618 | 18 | 234 | 15.3 | 2.6 |

Assays were performed on the specified fractions of the gradient in Figure 2 in the presence of 10% (v/v) glycerol. pH ratio is the ratio between the activity measured at pH 6.4 and that measured at pH 7.5.

To understand whether FC-induced activation of the PM H+-ATPase depends on an interaction with the FC-FCBP complex, it was necessary to find experimental conditions that would separate the two proteins. Marra et al. (1996) recently reported that, in PM from maize (Zea mays) roots incubated in vivo with FC, washed with Triton X-100 prior to solubilization with dodecyl-β-d-maltoside, and purified by DEAE-anion-exchange HPLC, the PM H+-ATPase and bound [3H]FC showed distinct elution profiles. We applied the same solubilization protocol to C-PM and FC-PM from radish seedlings. Table V shows the PM H+-ATPase activity measured in native PM, in the pellet obtained after washing PM with Triton X-100, and in the pellet and SN obtained after solubilization with dodecyl-β-d-maltoside. Treatment of the PM with Triton X-100 caused an approximate 30% decrease in the PM H+-ATPase activity, which was restored by the addition of asolectin. Solubilization of Triton-X-100-washed PM with dodecyl-β-d-maltoside determined an almost complete loss of the PM H+-ATPase activity, both in the pellet and in the soluble fractions, probably due to delipidation of the enzyme. The solubilized PM H+-ATPase activity of both C-PM and FC-PM was partially restored by the addition of asolectin.

Table V.

Solubilization of PM H+-ATPase from Triton X-100-washed C-PM and FC-PM

| PM Treatment | PM H+-ATPase Activity

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No addition

|

Asolectin

|

|||

| C-PM | FC-PM | C-PM | FC-PM | |

| nmol Pi min−1 | ||||

| Native | 353 (100%) | 398 (100%) | 331 (93%) | 390 (98%) |

| Triton X-100 | 246 (70%) | 278 (65%) | 334 (95%) | 378 (95%) |

| Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside | ||||

| Pellet | 17 (5%) | 24 (6%) | 25 (7%) | 32 (9%) |

| SN | 9 (2.5%) | 26 (6.5%) | 36 (10%) | 75 (19%) |

PM protein (1 mg) was treated with 0.36% (v/v) Triton X-100. Solubilization was performed with 10 mg mL−1 dodecyl-β-d-maltoside in the presence of 2 mg protein mL−1. PM H+-ATPase activity was assayed at pH 6.4 in the presence or absence of 300 μg mL−1 asolectin.

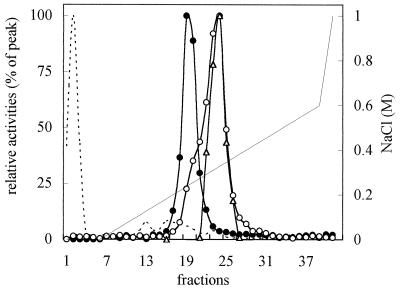

Proteins from C-PM and FC-PM, solubilized as described in Table V, were fractionated by FPLC on a Mono-Q column. Figure 3 shows the elution profiles of the PM H+-ATPase activity from C-PM and FC-PM and the FC-FCBP complex from FC-PM. When solubilized C-PM was fractionated, the PM H+-ATPase eluted as a narrow peak at approximately 0.25 m NaCl (fractions 17–22), in agreement with results obtained with other plant materials (Johansson et al., 1994). Fractionation of solubilized FC-PM gave a different PM H+-ATPase elution profile. In fact, in this case the PM H+-ATPase activity eluted between 0.24 and 0.36 m NaCl (peaking at fractions 23–24, corresponding to 0.31 m NaCl), with a shoulder between 0.24 and 0.27 m NaCl (fractions 19–21) that partially overlapped the peak of C-PM H+-ATPase activity.

Figure 3.

Elution profiles of PM H+-ATPase activity and the FC-FCBP complex after solubilization of 18 mg of C-PM and FC-PM proteins with dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (2 mg protein mL−1:10 mg detergent mL−1) and fractionation by FPLC Mono-Q anion-exchange column. •, PM H+-ATPase activity from C-PM; ○, PM H+-ATPase from FC-PM; ▵, FC-FCBP complex; dashed line, proteins; and continuous line, NaCl gradient. PM H+-ATPase activity, assayed in the presence of 300 μg mL−1 asolectin, and the amount of FC-FCBP complex are expressed as a percentage of the peak fraction (313.2 nmol Pi min−1 for C-PM, 156.6 nmol Pi min−1 for FC-PM, and 414-pmol-bound FC, respectively). PM H+-ATPase activity was measured at pH 6.4. Proteins in the peak fractions were 126 μg for C-PM and 72 μg for FC-PM.

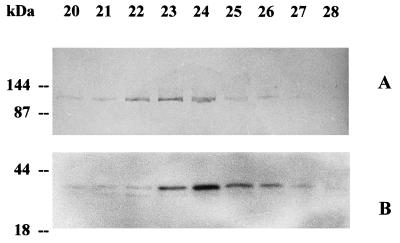

The FC-FCBP complex, measured by FC RIA in the fractions from FC-PM, showed a narrow peak at approximately 0.31 m NaCl, closely matching the major peak of the PM H+-ATPase activity. These results were confirmed by western analysis. As shown in Figure 4A, when the FPLC fractions from FC-PM were probed with an antiserum against the N-terminal domain of the PM H+-ATPase, the immunodecoration of the 100-kD polypeptide paralleled the elution profile of the PM H+-ATPase activity. The elution profile was asymmetric: the intensity of the bands increased from fractions 20 to 24, with a peak distributed between fractions 23 and 24, and then sharply decreased.

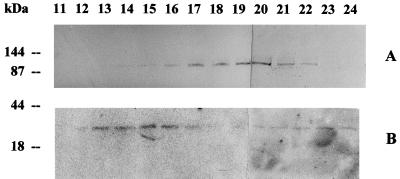

Figure 4.

Immunoblotting of fractions 20 to 28, eluted from an FPLC anion-exchange Mono-Q column of solubilized FC-PM. A, Immunodecoration with anti-N-terminus PM H+-ATPase antibodies; B, immunodecoration with anti-14–3-3 antibodies.

It was recently demonstrated that the FCBP belongs to the family of 14–3-3 proteins (Aitken et al., 1992; Korthout and de Boer, 1994; Marra et al., 1994; Morrison, 1994; Oeking et al., 1994; de Boer, 1997). A 20-amino acid synthetic peptide, corresponding to an N-terminal sequence of the 14–3-3 present in purified FCBP from corn shoots, was used to produce polyclonal antibodies (Marra et al., 1994). We utilized this antiserum to probe fractions of the FPLC from FC-PM (Fig. 4B). The antiserum labeled a band of 30 kD, and to a much lesser extent a slightly smaller band, in fractions 20 to 28. The immunodecoration of the 30-kD band showed a sharp peak at fraction 24, matching the elution profile of the FC-FCBP complex measured by FC RIA (Fig. 3); the higher sensitivity of this approach revealed the presence of the FCBP in fractions in which it was not detectable by FC RIA (compare fractions 20, 21, and 27 in Figs. 3 and 4B).

Figure 5A shows the results of western analysis of FPLC fractions 11 to 24 from C-PM probed with the antiserum against the N-terminal domain of the PM H+-ATPase. The immunodecoration of the 100-kD polypeptide matched the elution profile of the PM H+-ATPase activity (Fig. 3), with maximal intensity of the bands in fractions 19 and 20. The availability of the anti-14–3-3 antiserum allowed us to analyze the distribution of the FCBP in FPLC fractions from C-PM as well. Figure 5B shows the results of western analysis of fractions 11 to 24 from C-PM probed with the anti-14–3-3 antiserum. The immunodecoration of the 30-kD band indicated that in this case the FCBP elution profile was completely different with respect to the PM H+-ATPase, which was monitored for hydrolytic activity (Fig. 3) and by western analysis (Fig. 5A), and eluted between 0.15 and 0.25 m NaCl (fractions 12–17). Moreover, the elution profile of the FCBP from C-PM was markedly different from that of the FCBP from FC-PM, which eluted at a much higher NaCl concentration (see western blot in Fig. 4B and FC RIA in Fig. 3).

Figure 5.

Immunoblotting of fractions 11 to 24, eluted from FPLC anion-exchange Mono-Q column of solubilized C-PM. A, Immunodecoration with anti-N terminus PM H+-ATPase antibodies; B, immunodecoration with anti-14–3-3 antibodies.

As previously described, the FPLC profile obtained from FC-PM showed a shoulder of PM H+-ATPase between 0.24 and 0.27 m NaCl (fractions 19–21), where, as shown by western analysis (Fig. 4), PM H+-ATPase activity, and FC RIA (Fig. 3), the PM H+-ATPase and FCBP were partially separated. We compared the pH ratios of PM H+-ATPase activity in one fraction from C-PM (fraction 18) with two fractions from FC-PM showing similar PM H+-ATPase activity: fraction 21, in which the amount of FCBP was very low, and fraction 25, in which the two proteins co-eluted. Data in Table VI show that the pH ratios measured in fraction 18 from the C-PM profile and in fraction 25 from the FC-PM profile, which is within the peak of FC-FCBP, were similar to those measured in dodecyl-β-d-maltoside-solubilized PM H+-ATPase (Table III). Accordingly, the pH ratio measured in fraction 25 from FC-PM was about one-half that in fraction 18 from C-PM (3.4 versus 7.6), indicating that the PM H+-ATPase retained its activated state. In fraction 21 from FC-PM, in which the amount of FCBP was much lower than that of fraction 25, the pH ratio was 5.5, significantly higher than that measured in fraction 25, indicating that the PM H+-ATPase was partially inactivated in this fraction.

Table VI.

pH ratio of PM H+-ATPase activity in FPLC fractions from C-PM and FC-PM

| PM | Fraction | PM H+-ATPase

Activity

|

pH Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 6.4 | pH 7.5 | |||

| nmol Pi min−1 | ||||

| C-PM | 18 | 119 | 16 | 7.6 |

| FC-PM | 21 | 66 | 12 | 5.5 |

| FC-PM | 25 | 100 | 29 | 3.4 |

Assays were performed on the specified fractions of the FPLC Mono-Q column in Figure 3 in the presence of 300 μg mL−1 asolectin. The pH ratio is the ratio between the activity measured at pH 6.4 and that measured at pH 7.5.

DISCUSSION

In this paper we present evidence indicating that in vivo treatment of radish seedlings with FC causes an association between the PM H+-ATPase and the FC-FCBP complex necessary for the activation of the PM H+-ATPase.

The starting point of this work was our previous observation that in PM isolated from both A. thaliana and radish seedlings the stoichiometry between the FCBP and the PM H+-ATPase was close to one-to-one, suggesting that FC-induced activation of the PM H+-ATPase depends on a molecular interaction of the FC-FCBP complex with the enzyme (De Michelis et al., 1996b).

To further investigate this hypothesis, we utilized experimental conditions supposed to separate the two proteins and we analyzed the dependence of the FC-induced activation of PM H+-ATPase on its association with the FC-FCBP complex. Different detergents with diverse chemical characteristics solubilize the PM H+-ATPase and the FC-FCBP complex from FC-PM to similar extents (Table I–III). Moreover, the distribution profiles of PM H+-ATPase activity and of the FC-FCBP complex obtained by fractionation of solubilized FC-PM on a linear-density Suc gradient indicate that the two proteins comigrate (Fig. 2). These results are in agreement with the partial cosedimentation of the PM H+-ATPase activity with bound [3H]FC observed when microsomes from radish seedlings treated in vitro with FC were solubilized and fractionated on a Suc-density gradient (Cocucci and Marrè, 1991).

Marra et al. (1996) recently reported that in PM from maize roots incubated in vivo with FC, washed with Triton X-100 prior to solubilization with dodecyl-β-d-maltoside, and purified by DEAE-anion-exchange HPLC the PM H+-ATPase and bound [3H]FC showed distinct elution profiles. We applied the same experimental conditions to fractionate solubilized C-PM and FC-PM from radish seedlings by FPLC on a Mono-Q anion-exchange column but obtained only a partial separation of the two proteins (Fig. 3 and 4). In fact, both measurements of PM H+-ATPase activity and the FC-FCBP complex and western analysis performed with antibodies against the PM H+-ATPase and the 14–3-3 protein present in purified FCBP from different plant materials (Korthout and de Boer, 1994; Marra et al., 1994; Oecking et al., 1994) showed that the bulk of PM H+-ATPase and FCBP from FC-PM coelute between 0.24 and 0.36 m NaCl, with a peak at 0.31 m NaCl. Only a minor fraction of the PM H+-ATPase elutes at lower NaCl concentrations partially separated from the FCBP.

It is worth noting that, in agreement with previous observations (Johansson et al., 1994), the PM H+-ATPase from C-PM elutes at approximately 0.25 m NaCl, corresponding with the shoulder of PM H+-ATPase from FC-PM, where the enzyme is partially separated from the FCBP. Moreover, the 30-kD band of C-PM recognized by antibodies against the 14–3-3 elutes between 0.15 and 0.25 m NaCl, earlier than the PM H+-ATPase. Thus, FC treatment of the seedlings causes the establishment of a complex between the FCBP and the PM H+-ATPase. This complex, which might also involve other proteins, is stable to the solubilization procedure and elutes at a NaCl concentration higher than that necessary to elute the two proteins from C-PM. The discrepancy between our results and similar recently reported data (Piotrowsky et al., 1996) obtained with PM isolated from FC-treated leaves of Commelina communis and data obtained by Marra et al. (1996) from PM isolated from maize roots might reflect a weaker stability of the complex in graminaceous plants, but further investigations are necessary to understand this aspect.

As previously mentioned, FPLC fractionation of FC-PM allows partial separation of PM H+-ATPase from FCBP corresponding to fractions 19 to 21 (Figs. 3 and 4), where the relative amount of FC-FCBP is much lower than that of PM H+-ATPase. Analysis of the activation state of PM H+-ATPase (Table VI) in these fractions partially deprived of FCBP indicates that separation of the two proteins leads to inactivation of PM H+-ATPase, thus suggesting that the association between the FC-FCBP complex and PM H+-ATPase is necessary to the FC-induced activation of the enzyme.

Marra et al. (1996) showed that in FC-treated maize roots the PM H+-ATPase, once separated from the FCBP, retained its activated state. These results would be suggestive of an FC-induced covalent modification of the PM H+-ATPase; however, in those experiments western analysis to confirm the elution profile of the PM H+-ATPase activity was performed with an anti-C-terminus H+-ATPase antibody, which would not detect proteolyzed PM H+-ATPase activated by removal of the C-terminal domain (Palmgren et al., 1990, 1991; Rasi-Caldogno et al., 1993). On the other hand, Piotrowsky et al. (1996) recently showed that proteolytic removal of the C terminus leads to the release of FCBP from PM, suggesting that FCBP-specific 14–3-3 interacts directly with the PM H+-ATPase, presumably near or at the C terminus.

Data from several laboratories obtained with different plant materials indicate that FC binding to the FCBP stabilizes the coupling between FCBP and the PM H+-ATPase (Cocucci and Marrè, 1991; Korthout and de Boer, 1994; Oecking et al., 1994; De Michelis et al., 1996b; Piotrowsky et al., 1996). Evidence in this paper clearly confirms this association and indicates that it is necessary for activation of the PM H+-ATPase. The involvement of other proteins (e.g. protein kinases) in the formation of the complex cannot be ruled out. However, the lack of activation upon separation from the FC-FCBP complex suggests that activation does not depend on a covalent modification of the PM H+-ATPase.

Altogether, our results are in agreement with a recently proposed model for FC-induced activation of the PM H+-ATPase (de Boer, 1997). In this model the 14–3-3 forms a bridge between two domains of the PM H+-ATPase located in the C terminus and central loop (Aitken, 1996; Piotrowsky et al., 1996), analogous to the model for the Raf kinase-14–3-3 protein interaction (Aitken, 1996). In this conformation, the activity of the enzyme is low but stable. Activation of the PM H+-ATPase by different modulators such as FC, phosphatase 2A, or the phospho-Ser-259-Raf-1 peptide (Moorhead et al., 1996) would lead to the dissociation of the 14–3-3 from one domain, which by unfolding would determine the activation of the enzyme by dimerization or oligomerization, as reported for 14–3-3-induced oligomerization of Raf (Farrar et al., 1996). In light of the data available so far, the alternative proposed model, which explains the FC-induced activation of the PM H+-ATPase as due to the dissociation of 14–3-3 from the enzyme (Moorhead et al., 1996), is not supported by experimental evidence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Patrizia Aducci and Mauro Marra (Dipartimento di Biologia, Università di Roma Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy) for the generous gift of antiserum anti-FC and anti-14–3-3.

Abbreviations:

- Chaps

3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethyl-ammonio]-1-propane-sulfonate

- FC

fusicoccin

- FCBP

FC-binding protein

- FPLC

fast-protein liquid chromatography

- [3H]FC

[3H]dihydrofusicoccin

- lysoPC

lysophosphatidylcholine

- PM

plasma membrane

- RIA

radioimmunoassay

- SN

supernatant

Footnotes

This work was supported by Ministero per le Risorse Agricole, Alimentari e Forestali in the frame of the Piano Nazionale per le Biotecnologie Vegetali and by Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, coordinated project Membrane, Apoplasto e Omeostasi Cellulare.

LITERATURE CITED

- Aducci P, Ballio A. Mode of action of fusicoccin: the role of specific receptors. In: Graniti A, Durbin DB, Ballio A, editors. Phytotoxins and Plant Pathogenesis. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1989. pp. 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Aducci P, Ballio A, Fogliano V, Fullone MR, Marra M, Proietti M. Purification and photoaffinity labeling of fusicoccin receptors from maize. Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:339–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aducci P, Marra M, Fogliano V, Fullone MR. Fusicoccin receptors: perception and transduction of the fusicoccin signal. J Exp Bot. 1995;46:1463–1478. [Google Scholar]

- Aitken A. 14–3-3 and its possible role in coordinating multiple signalling pathways. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:341–347. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)10029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken A, Collinge DB, Van Heusden GPH, Isobe T, Roseboom PH, Rosenfeld G, Soll J. 14–3-3 proteins: a highly conserved, widespread family of eukaryotic proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:498–501. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90339-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocucci MC, Marrè E. Co-sedimentation of one form of plasma membrane proton-ATPase and of the fusicoccin receptor from radish microsomes. Plant Sci. 1991;73:45–49. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer B. Fusicoccin—a key to multiple 14–3-3 locks? Trends Plant Sci. 1997;2:60–66. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer AH, Watson BA, Cleland RE. Purification and identification of the fusicoccin binding protein from oat root plasma membrane. Plant Physiol. 1989;89:250–259. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.1.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Michelis MI, Papini R, Pugliarello MC. Multiple effects of lysophosphatidylcholine on the activity of the plasma membrane H*-ATPase of radish seedlings. Bot Acta. 1996a;110:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- De Michelis MI, Rasi-Caldogno F, Olivari C, Carnelli A, Pugliarello MC. Controlled proteolysis affects the regulatory properties of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase and Ca-ATPase. In: Taiz L, editor. Proceedings of the Ninth International Workshop on Plant Membrane Biology (abstract 91). Department of Biology, Santa Cruz: University of California; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- De Michelis MI, Rasi-Caldogno F, Pugliarello MC, Olivari C. Fusicoccin binding to its plasma membrane receptor and the activation of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase. II. Stimulation of the H+-ATPase in a plasma membrane fraction purified by phase partitioning. Bot Acta. 1991;104:265–271. [Google Scholar]

- De Michelis MI, Rasi-Caldogno F, Pugliarello MC, Olivari C. Fusicoccin binding to its plasma membrane receptor and the activation of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase. III. Is there a direct interaction between the fusicoccin receptor and the plasma membrane H+-ATPase? Plant Physiol. 1996b;110:957–964. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.3.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar MA, Alberola-Ila J, Perlmutter RM. Activation of the Raf-1-kinase cascade by coumermycin-induce dimerization. Nature. 1996;383:178–181. doi: 10.1038/383178a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JF, Manney L, Dewitt ND, Yoo MH, Sussman MR. The Arabidopsis thaliana plasma membrane H+-ATPase multigene family. Genomic sequence and expression of a third isoform. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13601–13607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson F, Sommarin M, Larsson C. Fusicoccin activates the plasma membrane H+-ATPase by a mechanism involving the C-terminal inhibitory domain. Plant Cell. 1993;5:321–327. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.3.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson F, Sommarin M, Larsson C. Rapid purification of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase in its non-activated form using FPLC. Physiol Plant. 1994;92:389–396. [Google Scholar]

- Korthout HAAJ, de Boer AH. A fusicoccin binding protein belongs to the family of 14–3-3 brain protein homologs. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1681–1692. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.11.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthout HAAJ, van der Hoeven PCJ, Wagner MJ, Van Hunnik E, de Boer AH. Purification of the fusicoccin-binding protein from oat plasma membrane by affinity chromatography with biotinylated fusicoccin. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:1281–1288. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.4.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfermeijer FC, Prins HBA. Modulation of H+-ATPase activity by fusicoccin in plasma membrane vesicles from oat (Avena sativa L.) roots. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:1277–1285. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.4.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markwell MAK, Haas SM, Bieber LL, Tolbert NE. A modification of the Lowry procedure to simplify protein determination in membrane and lipoprotein samples. Anal Biochem. 1978;87:206–210. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90586-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra M, Fogliano V, Zambardi A, Fullone MR, Nasta D, Aducci P. The H+-ATPase purified from maize root plasma membranes retains fusicoccin in vivo activation. FEBS Lett. 1996;382:293–296. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra M, Fullone MR, Fogliano V, Pen J, Mattei M, Masi S, Aducci P. The 30-kilodalton protein present in purified fusicoccin receptor preparations is a 14–3-3-like protein. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1497–1501. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrè E. Fusicoccin: a tool in plant physiology. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1979;30:273–288. [Google Scholar]

- Marrè E, Bellando M, Beffagna N, Marrè MT, Romani G, Vergani P. Synergisms, additive and non additive factors regulating proton extrusion and intracellular pH. Curr Top Plant Biochem Physiol. 1993;11:213–230. [Google Scholar]

- Moorhead G, Douglas P, Morrice N, Scarabel M, Aitken A, MacKintosh C. Phosphorylated nitrate reductase from spinach leaves is inhibited by 14–3-3 proteins and activated by fusicoccin. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1104–1113. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70677-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison D. 14–3-3: modulators of signaling proteins? Science. 1994;266:56–57. doi: 10.1126/science.7939645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oecking C, Eckerskorn C, Weiler EW. The fusicoccin receptor of plants is a member of the 14–3-3 superfamily of eukaryotic regulatory proteins. FEBS Lett. 1994;352:163–166. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00949-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oecking C, Weiler EW. Characterization and purification of the fusicoccin binding complex from plasma membrane of Commelina communis. Eur J Biochem. 1991;199:685–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivari C, Pugliarello MC, Rasi-Caldogno F, De Michelis MI. Bot Acta. 1993;106:13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Palmgren MG, Larsson C, Sommarin M. Proteolytic activation of the plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase by removal of a terminal segment. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13423–13426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmgren MG, Sommarin M, Serrano R, Larsson C. Identification of an autoinhibitory domain in the C-terminal region of the plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20470–20475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowsky M, Hagemeier J, Hagemann K, Oecking C (1996) Functional architecture of the fusicoccin receptor. Plant Physiol Biochem (Special Issue) 14: 184–185

- Rasi-Caldogno F, Carnelli A, De Michelis MI(1995) Identification of the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase and its autoinhibitory domain. Plant Physiol 108: 105–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rasi-Caldogno F, De Michelis MI, Pugliarello MC, Marrè E. H+-pumping driven by the plasma membrane ATPase in membrane vesicles from radish: stimulation by fusicoccin. Plant Physiol. 1986;82:121–125. doi: 10.1104/pp.82.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasi-Caldogno F, Pugliarello MC. Fusicoccin stimulates the H+-ATPase of plasmalemma in isolated membrane vesicles from radish. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;133:280–285. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)91872-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasi-Caldogno F, Pugliarello MC, Olivari C, De Michelis MI. Controlled proteolysis mimics the effect of fusicoccin on the plasma membrane H+-ATPase. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:391–398. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regenberg B, Villalba JM, Lanfermeijer FC, Palmgren MG. C-terminal deletion analysis of plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase: yeast as a model for solute transport across the plasma membrane. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1655–1666. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.10.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz S, Oelgemoller E, Weiler EW. Fusicoccin action in cell-suspension cultures of Corydalis sempervirens Pers. Planta. 1990;183:83–91. doi: 10.1007/BF00197571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler EW, Meyer C, Oecking C, Feyerabend M, Mithofer A. The fusicoccin receptor of higher plants. In: Lamb CJ, Beachy RN, editors. Plant Gene Transfer. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1990. pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar]