Abstract

The gene causative for the human nonsyndromic recessive form of deafness DFNB22 encodes otoancorin, a 120-kDa inner ear-specific protein that is expressed on the surface of the spiral limbus in the cochlea. Gene targeting in ES cells was used to create an EGFP knock-in, otoancorin KO (OtoaEGFP/EGFP) mouse. In the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse, the tectorial membrane (TM), a ribbon-like strip of ECM that is normally anchored by one edge to the spiral limbus and lies over the organ of Corti, retains its general form, and remains in close proximity to the organ of Corti, but is detached from the limbal surface. Measurements of cochlear microphonic potentials, distortion product otoacoustic emissions, and basilar membrane motion indicate that the TM remains functionally attached to the electromotile, sensorimotor outer hair cells of the organ of Corti, and that the amplification and frequency tuning of the basilar membrane responses to sounds are almost normal. The compound action potential masker tuning curves, a measure of the tuning of the sensory inner hair cells, are also sharply tuned, but the thresholds of the compound action potentials, a measure of inner hair cell sensitivity, are significantly elevated. These results indicate that the hearing loss in patients with Otoa mutations is caused by a defect in inner hair cell stimulation, and reveal the limbal attachment of the TM plays a critical role in this process.

The sensory epithelium of the cochlea, the organ of Corti (Fig. 1), contains two types of hair cell, the purely sensory inner hair cells (IHCs) and the electromotile, sensorimotor outer hair cells (OHCs). These cells are critically positioned between two strips of ECM, the basilar membrane (BM) and the tectorial membrane (TM). Signal processing in the cochlea is initiated when sound-induced changes in fluid pressure displace the BM in the transverse direction, causing radial shearing displacements between the surface of the organ of Corti (the reticular lamina) and the overlying TM (1). The radial shear is detected by the hair bundles of the IHCs and the OHCs (2), with the stereocilia of the OHC hair bundles forming an elastic link between the organ of Corti and the overlying TM (3). Deflection of the stereocilia gates the hair cell’s mechanoelectrical transducer (MET) channels, thereby initiating a MET current (4) that promotes active mechanical force production by the OHCs, which, in turn, influences mechanical interactions between the TM and the BM (5, 6). This nonlinear frequency-dependent enhancement process, which boosts the sensitivity of cochlear responses to low-level sounds and compresses them at high levels, is known as the cochlear amplifier (7).

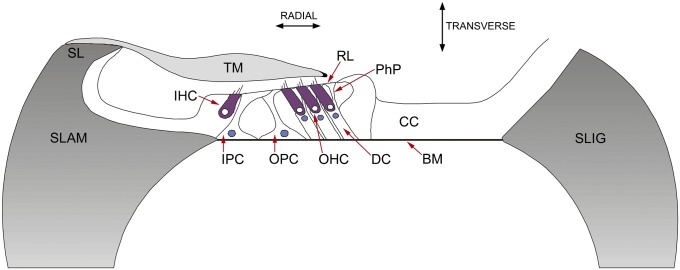

Fig. 1.

Schematic cross-section of WT cochlea. Spiral lamina (SLAM), spiral ligament (SLIG), inner pillar cells (IPC), outer pillar cells (OPC), Deiters' cells (DC), phalangeal process of DC (PhP), Claudius cells (CC), OHC, IHC, reticular laminar (RL), spiral limbus (SL), and major noncellular elements (BM and TM).

Whereas the hair bundles of the OHCs are imbedded into the TM and therefore directly excited by relative displacement of the undersurface of the TM and the reticular lamina, those of the IHCs are not in direct contact with the TM, and the way in which they are driven by motion of the BM remains unclear. Intracellular recordings of the receptor potentials in IHCs indicate that the bundles are velocity-coupled (to fluid flow) at low frequencies and displacement-coupled at higher frequencies of stimulation (2, 8, 9). Direct measurements of the motion of the reticular lamina and the lower surface of the TM in an ex vivo preparation of the guinea pig cochlea provide evidence that, at frequencies below 3 kHz, counterphase transverse movements of the two surfaces generate pulsatile fluid movements in the subtectorial space that could drive the hair bundles of the IHCs (10). At higher frequencies, the two surfaces move in phase, and radial shear alone is thought to dominate. Theoretical studies (11) reveal that the boundary layers will be vanishingly thin at high frequencies, that the fluid in the gap between the TM and the reticular lamina will be inviscid, and that the hydrodynamic forces on the hair bundle will be inertial. Although an overlying TM that is not directly attached to a hair bundle does not apply torque to the hair bundle (11), the inertial force of the fluid driving the hair bundle depends on its mass and therefore the size of the gap between the reticular lamina and the TM (11, 12).

The TM is composed of radially arrayed collagen fibrils that are imbedded in a noncollagenous matrix composed of a number of different glycoproteins, including Tecta, Tectb, otogelin, otolin, and Ceacam16 (13–16). Mutations in Tecta cause recessive (DFNB21) and dominant (DFNA8/12) forms of human hereditary deafness (17–19), and a dominant missense mutation in Ceacam16 (DFNA4) has been identified recently as a cause of late-onset progressive hearing loss in an American family (15). Mutations in Tecta are one of the most common causes of autosomal-dominant, nonsyndromic hereditary hearing loss (20), and mouse models for the recessive (21) and dominant (22) forms of deafness arising from mutations in Tecta have been created. Together with data from a Tectb-null mutant mouse (23), these studies have provided evidence that the TM plays multiple roles in hearing (24). Although much is known about the structure of the TM, an ECM that is unique to the cochlea, relatively little is known about how it attaches to the apical surface of the cochlear epithelium. Otoancorin, a product of the DFNB22 locus, is expressed on the apical surface of the spiral limbus and has been suggested to mediate TM attachment to this region of the cochlear epithelium (25). In this study, we use gene targeting to inactivate otoancorin. This provides a mouse model for DFNB22, reveals a loss of IHC sensitivity as the primary cause of deafness, and isolates a specific role for the limbal attachment of the TM in driving the hair bundles of the IHCs.

Results

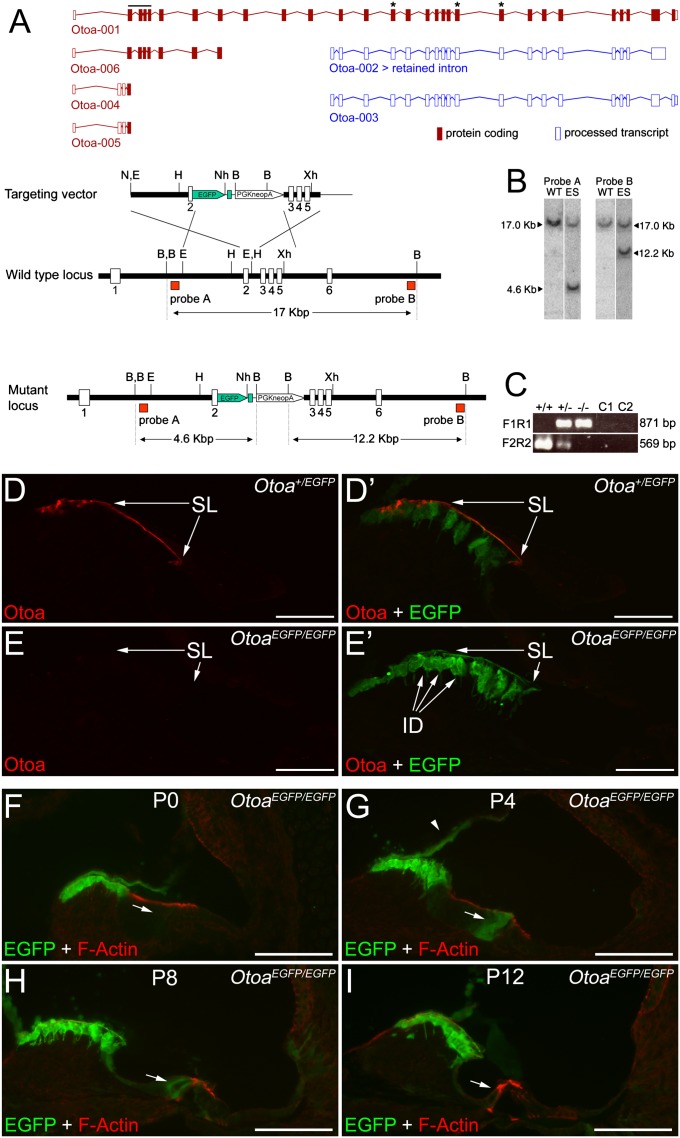

Gene targeting in ES cells was used to replace the first coding exon of the murine Otoa gene with a cassette encoding EGFP (Fig. 2A). Southern blotting with probes located external to the targeting vector was used to detect and confirm successful targeting (Fig. 2B), and one ES cell line was used to produce a chimeric mouse that transmitted through the germ line. Full-length Otoa mRNA cannot be detected in the cochleae of OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice by RT-PCR (Fig. 2C). EGFP is observed in the interdental cells of the spiral limbus in mature mice that are heterozygous (i.e., Otoa+/EGFP) for the targeted mutation, and otoancorin is detected on the apical surface of the limbus with an antibody (25) raised to two peptides located in the predicted C-terminal region of this protein (Fig. 2 D and D′). In homozygous OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice, EGFP expression levels in the interdental cells are higher and otoancorin immunoreactivity cannot be detected on the surface of the spiral limbus (Fig. 2 E and E′). Although shorter alternative transcripts are predicted that could be expressed in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse (Fig. 2A), these should be recognized by the antibody and are therefore unlikely to be translated. EGFP expression is also observed in the border cells that lie immediately adjacent and just medial to the IHCs, and in the cells of Reissner's membrane between postnatal days 4 and 12 in OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice (Fig. 2 F–I). These results indicate the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse is a null mutant at the level of protein expression, and confirm previous immunocytochemical studies (25) showing that otoancorin is expressed in the interdental cells of the spiral limbus, and, during a brief period of postnatal development, in the border cells that lie next to the IHCs.

Fig. 2.

Targeted insertion of EGFP into exon 2 of Otoa: (A) Otoa transcripts from Ensembl (shown above maps of the targeting vector), the 5′ region of the Otoa gene, and the targeted Otoa locus. Upper: Full-length Otoa transcript and five other putative splice variants predicted from EST clones. The horizontal black line indicates exons 2 to 5 of Otoa, and asterisks indicate exons 14, 20, and 21 that encode the peptide sequences used to raise the otoancorin antiserum (25). Splice variants Otoa-001, -004, -005, and -006 would be disrupted by the targeting approach used, and variants Otoa-002 and -003 would contain the peptide epitopes recognized by the otoancorin antiserum if they were independently expressed in the mutant. Lower: Dark bars represent intronic DNA, open boxes represent exons, and red boxes indicate external probes A and B used to confirm correct targeting. Sizes of the expected restriction fragments are indicated. Dashed lines indicate likely regions of homologous recombination. (B) Southern blots of BamHI digested DNA from WT and targeted ES cell DNA probed with external probes A and B as indicated in A. In addition to the WT band of 17 kb, a band of 4.6 kb is observed with probe A and a band of 12.2 kb with probe B. (C) RT-PCR using primers spanning exon 2 to the bovine growth hormone pA signal (F1R1) and exons 3 to 9 (F2R2). A PCR product indicating mRNA expression from the targeted locus is observed in Otoa+/EGFP (+/−) and OtoaEGFP/EGFP (−/−) RT-PCR reactions only, whereas the WT PCR product is observed only in Otoa+/+ and Otoa+/EGFP RT-PCR reactions. C1, no RT control; C2, no DNA control. (D and E) Confocal images of cryosections from the cochleae of Otoa+/EGFP (D and D′) and OtoaEGFP/EGFP (E and E′) mice double-immunolabeled with antibodies to otoancorin (red channel; D, D′, E, and E′) and GFP (green channel; D′ and E′). ID, interdental cells; SL, spiral limbus. (F–I) Confocal images of cryosections from the cochleae of OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice at postnatal day (P) P0 (F), P4 (G), P8 (H), and P12 (I) double-labeled with Texas red phalloidin to reveal F-actin (red channel) and GFP (green channel). Arrows indicate border cell region; arrowhead (G) indicates Reissner's membrane. (Scale bars: D and E’, 50 μm; F–I, 100 μm.)

TM Is Detached from Spiral Limbus in OtoaEGFP/EGFP Mice.

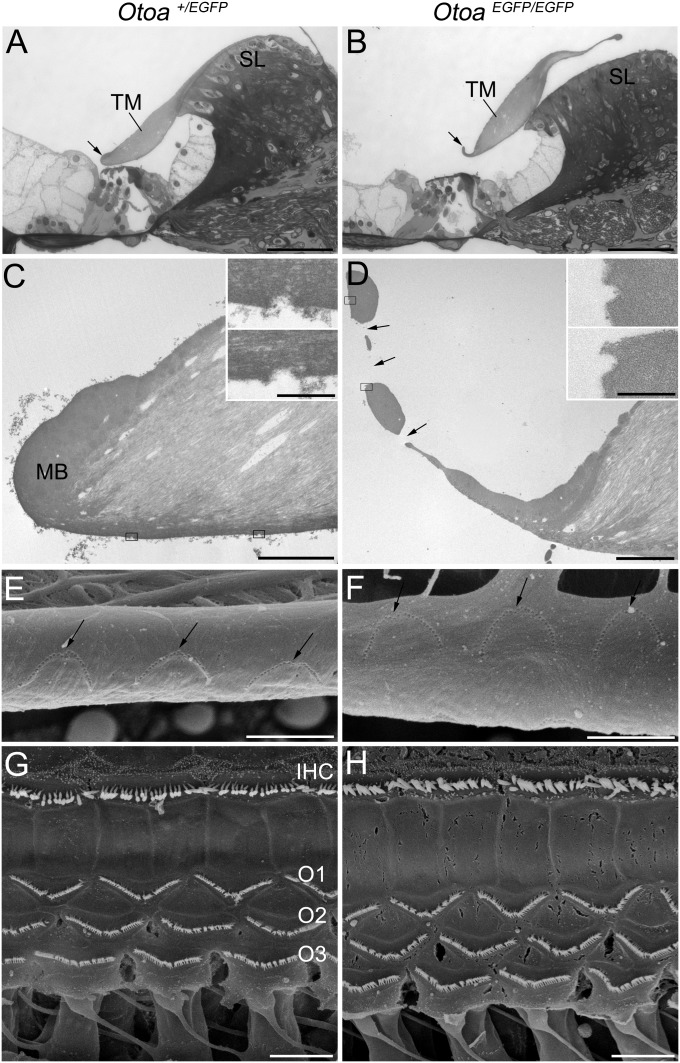

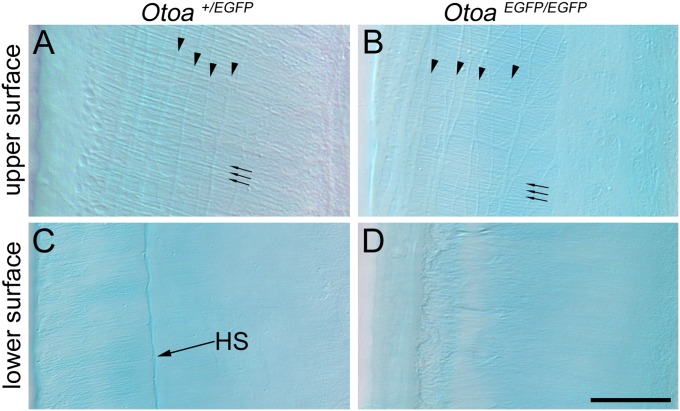

In WT and Otoa+/EGFP mice, the medial edge of the TM is closely apposed and attached to the spiral limbus, and the lateral region lies over the apical surface of the hair cells in the organ of Corti (Fig. 3A). In the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse, the TM is detached from the spiral limbus and the lateral-most region is markedly thinner than normal (Fig. 3B). This region is frequently seen to be fenestrated in the homozygous mutants and a typical marginal band, as seen in WT and heterozygous mice, is not present (Fig. 3 C and D). Although the TM in the homozygous mutants often appears to be slightly tilted, with the lateral region displaced medially with respect to the organ of Corti, hair bundle imprints, the sites at which the hair bundles of the OHCs attach to the lower surface of the TM, are observed by transmission EM and SEM (Fig. 3 C–F). Despite these changes in the structure and attachment of the TM in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse, SEM reveals that the orientation and organization of the hair bundles of the IHCs and OHCs in the organ of Corti are normal, and similar to that observed in WT (not shown) and heterozygous mice (Fig. 3 G and H). Differential interference contrast microscopy indicates the collagen fibril bundles of the TM are, as in heterozygotes and WT, distributed radially within the core of the matrix in the homozygous mutants (Fig. 4 A and B). The covernet, a network formed by fibrils that are aligned mainly along the length of the upper surface of the TM, is also of normal appearance (Fig. 4 A and B). Hensen's stripe, a ridge that runs longitudinally along the lower surface of the TM and is thought to engage the hair bundle of the IHCs, is, however, not visible in the homozygous mutants (Fig. 4 C and D).These observations show that otoancorin is required for adhesion of the TM to the spiral limbus and that the TM, despite the structural abnormalities described here, retains its gross overall form, remaining in close proximity with the organ of Corti.

Fig. 3.

Characterization of the mutant phenotype. Structure of organ of Corti and TM in mature Otoa+/EGFP (A, C, E, and G) and OtoaEGFP/EGFP (B, D, F, and H) mice. (A and B) Toluidine blue-stained, 1-μm-thick plastic sections: TM is detached from the spiral limbus (SL) in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse. Arrows indicate marginal band (A) and equivalent region in the mutant (B). (C and D) Transmission EM images showing ultrastructural details of lateral margin of TM. A prominent marginal band (MB) is visible in the Otoa+/EGFPmouse (C). This region is thinned and fenestrated (arrows) in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse (D). Insets: Details of boxed areas shown at higher magnification reveal imprints of tallest stereocilia of OHCs. (E and F) SEM of lower surface of TM revealing W-shaped imprints (arrows) of the OHC hair bundles. These are observed around the fenestrae in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse. (G and H) SEM revealing the hair bundles of the IHC and three rows of OHCs (O1, O2, and O3) in the organ of Corti. The structure and arrangement of these hair bundles is similar in mice of both genotypes. (Scale bars: A and B, 50 μm; C–H, 5 μm; C and D, Insets, 500 nm.)

Fig. 4.

Differential interference contrast microscopy of TMs. Images of the upper (A and B) and lower (C and D) surfaces of unfixed, Alcian blue-stained TMs from the basal end of the cochlea of Otoa+/EGFP (A and C) and OtoaEGFP/EGFP (B and D) mice at 7 wk of age. Covernet fibrils (arrowheads) and radial collagen fibrils (arrows) are visible in mice of both genotypes. Hensen's stripe (HS) is not visible in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice. (Scale bar: 20 μm.)

Cochlear Microphonic Potentials Are Symmetrical in OtoaEGFP/EGFP Mice.

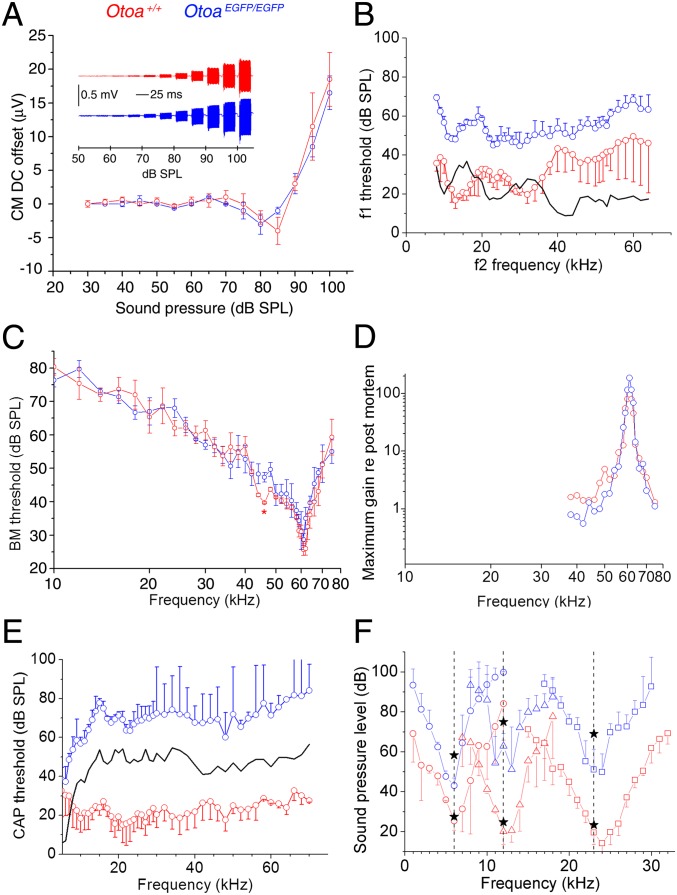

Cochlear microphonic (CM) potentials are extracellular potentials derived from the transducer currents of the OHCs (1, 26–28), and their symmetrical nature is known to result from the presence of the TM biasing the operating point of the hair bundle (21, 29). Although the TM is detached from the spiral limbus in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice, the CM potentials recorded from the round window of OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice are similar to those recorded from WT mice (Fig. 5A), being symmetric at low to moderate sound levels, becoming negatively and then positively asymmetrical with increasing sound levels greater than 80 dB sound pressure level (SPL) (29). The DC component of the CM potentials, a measure of their symmetry, only differs significantly (P ≤ 0.001) at 85 dB SPL, the inflection point in WT Otoa mice, an indication that attachment of the TM to the limbus may be important for controlling this point of apparent mechanical instability. These data provide functional evidence that the hair bundles of OHCs are, as suggested by the presence of hair-bundle imprints, attached to the TM in the homozygous mutants.

Fig. 5.

Physiological responses of cochlea of WT (red) and OtoaEGFP/EGFP (blue) mice. (A) Inset: CM potentials recorded from round window in response to 10-kHz tones of increasing levels (low-pass filtered at 12 kHz). DC component of the CM (mean ± SD, n = 10 preparations each for WT and OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice). (B) DPOAE (2f1−f2, 0 dB SPL criterion, mean ± SD) as a function of the f2 frequency (f2/f1 ratio = 1.23). Black line indicates the mean difference between measurements from four WT and four OtoaEGFP/EGFP samples. (C) Isoresponse BM frequency tuning curves (0.2 nm criterion; mean ± SD, n = 4 WT and n = 4 OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice with CFs between 59 and 61 kHz). Red asterisk indicates a second peak of sensitivity on the low-frequency shoulder of the WT tuning curve where the values for frequencies of 44, 46, and 48 kHz are significantly different (P ≤ 0.001) from those in the mutant tuning curve. (D) Difference in maximum gain measured in a single living preparation vs. measurements made postmortem (re postmortem). (E) Auditory nerve, compound action-potential threshold curves as a function of stimulus tone frequency (mean ± SD). Black line indicates the mean difference between five WT and four OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice. (F) Masking tuning curves (mean ± SD, n = 10 preparations) for auditory nerve CAP (probe tone frequencies indicated by vertical dashed lines; levels are indicated by black stars; lower stars indicate probe level for WT mice; upper stars indicate level for OtoaEGFP/EGFP. Bandwidth measured 10 dB above tip/probe tone frequency (Q10 dB) at the probe tone frequencies of 6, 12, and 23 kHz are 2.3 ± 0.4, 4.6 ± 0.5, and 7.2 ± 0.7 for WT and 3.2 ± 0.2, 7.5 ± 0.5, and 12.1 ± 3.8 for OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice, respectively. All mice are <3-mo-old littermates.

Cochlear Amplification Is Not Significantly Affected in OtoaEGFP/EGFP Mice.

Distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs) are a nonlinear acoustical response produced by the cochlea in response to simultaneous stimulation with two pure tones. A 10- to 35-dB elevation in threshold is observed for DPOAEs in the 8- to 65-kHz, low-threshold region of the cochlea (30) in OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice (Fig. 5B), with the difference being restricted to ≤20 dB in the basal region, where we are able to measure BM responses. If one assumes that these changes in DPOAE threshold reflect changes in the gain of the cochlear amplifier, and that the amplifier provides a gain of 60 dB in the low-threshold region of the mammalian cochlea, the feedback efficiency from the OHCs in the 8- to 65-kHz region of the cochlea in OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice is decreased by only approximately 3%. Measurements of the BM responses from the 55- to 65-kHz, high-frequency end of the cochlea in OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice provide direct confirmation that cochlear amplification remains close to normal when the TM is detached from the spiral limbus (Fig. 5 C and D). The sensitivity and sharpness of tuning given by the ratio of the CF to the bandwidth measured 10 dB from the tip in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP and WT mice do not differ significantly (P = 0.15; Table 1). The low-frequency shoulder of the BM tuning curves is, however, modified, and, at frequencies between 44 and 48 kHz, sensitivities are significantly different (P ≤ 0.001), and the threshold minimum observed in the tuning curve of the WT mice (Fig. 5C, red asterisk) is absent from that of the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice.

Table 1.

Parameters of BM tuning curves for WT and OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice

| Genotype | CF, kHz | Q10 dB | Threshold, dB SPL | Gain, dB | Animals |

| WT Otoa+/+ | 55–68 | 9.3 ± 1.50 | 27 ± 7 | 33 ± 7 | 5 |

| OtoaEGFP/EGFP | 55–65 | 8.2 ± 1.0 | 29 ± 4 | 30 ± 6 | 8 |

Q10 dB, bandwidth measured 10 dB above tip/probe tone frequency; Gain dB, with reference to postmortem.

Compound Action Potential Thresholds Are Significantly Elevated in OtoaEGFP/EGFP Mouse.

The compound action potential (CAP) is the synchronized activity of the auditory nerve fibers that is measured at the beginning of pure-tone stimulation. The thresholds for these potentials are elevated by 35 to 55 dB in the 8- to 70-kHz range in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice (Fig. 5E). Derived simultaneous masking neural tuning curves closely resemble the tuning of single auditory nerve fibers (31) and are known to become less sharp when cochlear amplification is compromised (32). Although the CAP thresholds of OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice are elevated, the CAP masking tuning curves derived from simultaneous tone-on-tone masking (31) are sharp, as would be expected if mechanical amplification were preserved (Fig. 5F). Two characteristics of the CAP masker tuning curves recorded from OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice further indicate cochlear amplification is not compromised and that nonlinear suppression (the basis for the tuning curves) is already manifested in the mechanical responses of the cochlear partition before the latter elicit neural excitation. First, the masker levels used are approximately 20 dB lower than the relatively high probe tone levels (Fig. 5F, upper black stars) necessary to elicit a measurable neural response for frequencies around the probe frequency. Second, the tuning curves are significantly sharper than those of WT mice (Fig. 5F), as has been observed previously for probe tone levels well above the mechanical threshold in sensitive, WT cochleae (22). These observations provide further evidence that the threshold of the mechanical responses is not significantly changed in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice, but that it is the transmission of these responses to the IHCs that is attenuated.

Discussion

The EGFP knock-in, Otoa KO mouse created in this study provides direct evidence that otoancorin is, as predicted (25), necessary for attachment of the TM to the spiral limbus. Although the TM is detached from the spiral limbus in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse, it remains in close proximity to the sensory epithelium, possibly via its attachment to the hair bundles of the OHCs. This is in contrast to the situation in the TectaΔENT/ΔENT mouse, in which a residual TM is completely divorced from the organ of Corti and ectopically associated with Reissner's membrane (20). Otoancorin is not expressed in OHCs, and another protein must therefore mediate adhesion of the OHC stereocilia to the TM. Although otoancorin and stereocilin share some long-range homology (33), and despite the absence of hair-bundle imprints in the TMs of stereocilin null mice (25), functional interactions between the TM and the OHCs do not require stereocilin (34). Distinct molecular mechanisms may therefore mediate interactions between the TM and the OHCs, but also between the TM and the spiral limbus.

The TM proteins with which otoancorin interacts are not yet known. Collagens are still present in the detached TMs of the TectaΔENT/ΔENT mouse (20), so limbal attachment is unlikely to be mediated by this class of protein. All the major noncollagenous proteins of the TM (Tecta, Tectb, and Ceacam16) are absent from the residual, detached TMs of the TectaΔENT/ΔENT mouse (20), and the TM remains limbally attached in the Tectb−/− mouse, the Otog−/− mouse, and the Ceacam16−/− mouse (13, 22, 32). One can therefore deduce that Tecta is a likely interaction partner of otoancorin, although the more recently identified TM protein otolin (15) may also mediate adherence of the TM to the limbus via otoancorin.

Although the limbally detached TMs of OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice are grossly normal, Hensen's stripe is absent and the lateral region is thinned and fenestrated, lacking a distinct marginal band. Hensen's stripe forms during the later stages of postnatal development from a region on the lower surface of the TM known as the homogeneous stripe, a region that remains in contact with the surface of the cochlear epithelium medial to the IHCs while the spiral sulcus is forming. Contact with the epithelium, mediated by otoancorin, may therefore be required for the development of Hensen's stripe. It is unclear why the lateral region of the TM fails to develop correctly in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice, as Otoa is not expressed by the supporting cells of the organ of Corti—the pillar cells, Deiters' cells, or Hensen's cells.

The loss of limbal attachment and the abnormalities in TM structure described here have very little effect on the sensitivity and tuning of the BM response, cause a mild (∼20 dB) reduction in the threshold of the DPOAEs, and result in a substantial (50 dB) increase in the threshold of the neural tuning curves, although the neural responses remain sharply tuned. The limbal attachment of the TM is not therefore necessary for cochlear amplification and tuning, but is critically required to ensure that the response of the BM and the reticular lamina are transmitted to the hair bundles of the IHCs without any loss of sensitivity. Although it may seem surprising that the loss of TM attachment to the spiral limbus has little effect on BM sensitivity and tuning, this finding is indeed predicted by a lever-and-springs model of the cochlea (35). The radial motion of the reticular lamina is largely controlled by the displacement of its attachment point at the pillar head, its rotation being of secondary importance. Consequently, a change in the angular rotation of the reticular lamina is predicted to have little effect on radial shear of the OHC hair bundles and increases amplification of BM motion by a factor of 1.5 at most, i.e., 3 dB or less, an outcome supported by our findings.

The symmetry of the CM observed in OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice implies that the OHCs are working, as in WT mice, around the most sensitive point on their input–output function and therefore able to provide BM amplification with optimal gain (21). Furthermore, the symmetry of the CM implies that the OHCs are not acting, as previously suggested, against the radial stiffness of the TM provided by the limbal attachment to set their operating point (21, 29, 36), unless the TM is attached to some other structure lateral to the OHCs in an otoancorin-independent manner. Although there have been indications that the TM may be attached to the surface of Hensen's cells (37), morphological evidence for such an attachment is lacking (Fig. 3A). The operating point is therefore more likely to be set by the resting open probability of the MET channels, which is close to 50% in artificial endolymph containing low (0.02 mM) calcium levels (38). This raises the interesting possibility that the TM may passively regulate the local calcium ionic environment in the vicinity of the MET channels (39), and may also explain why the CM recorded from the organ of Corti of TectaΔENT/ΔENT (21) and TectaC1509G/C1509G (40) mice, where the TM is completely detached from the organ of Corti, is typically asymmetrical in form.

The timing of the forces that are fed back to the cochlear partition by the OHCs is crucial for cochlear amplification to be effective (20, 33–35), and depends on whether the OHC hair bundles are driven by the elastic or inertial forces delivered by the TM (33). For frequencies well below the characteristic frequency (CF; i.e., the frequency that produces the most sensitive response), the TM imposes an elastic load on the OHC bundles and they are displaced maximally in the excitatory direction (i.e., toward the tallest row of stereocilia) during maximum displacement of the cochlear partition toward the scala vestibuli (1, 36–40). For frequencies at and around the CF, however, it has been suggested that the OHCs are excited by the inertial force imposed by the TM (23). This excitation lags cochlear partition displacement by 0.5 cycles, so the OHC stereocilia are displaced maximally when the partition is displaced maximally toward the scala tympani (23). As a consequence of this, and as a result of the additional 0.25-cycle delay imposed by the membrane time constant, which appears to track the CF of the OHCs up to 8 kHz (38), the receptor potentials and the forces produced by somatic electromotility are in phase with the velocity of the cochlear partition. The sensitivity and sharpness of BM tuning found in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse indicate that the elasticity of the TM attachment to the spiral limbus is not a crucial factor for exciting the OHCs near their CF, and that the OHCs must react against, and therefore be excited by, the inertial load provided by the TM at CF to effectively boost the mechanical responses of the cochlea (22).

A second resonance has been observed approximately one half-octave below the tip of the BM tuning curve in measurements obtained from the basal, high-frequency end of the murine cochlea (20, 21). This feature of BM tuning curves has been previously attributed to the TM resonance (20, 23) and is thought to result from a reduction in the load imposed by the TM at its resonance frequency. Although the TM’s role as an inertial mass and a source of the second resonance had been deduced from previous studies of the TectaΔENT/ΔENT mouse, it was not possible to isolate a specific role for the elasticity of the limbal attachment region because the residual TM is completely detached from both the spiral limbus and the surface of the organ of Corti in the TectaΔENT/ΔENT mouse. The absence of a second resonance in the BM tuning curves of the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse in which the TM is detached from the spiral limbus now provides evidence that this resonance derives specifically from the elasticity of the TM’s attachment to the spiral limbus, combined with its effective mass.

Although the sensitivities of the BM responses recorded from WT and OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice are similar, DPOAEs recorded at similar frequencies differ by approximately 20 dB. Slight changes in the motion of the reticular lamina caused by changes in loading of the cochlear partition by the modified TM of the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse might cause this increase in DPOAE thresholds. The reticular lamina is, however, coupled compliantly to the BM via the OHC–Deiters' cell complex (41–44), so any change in the load on the cochlear partition would be expected to affect amplification of BM motion and be reflected in the vibrations of the BM. It is therefore more likely that this mild loss in the sensitivity of the DPOAEs in OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice results from the detachment of the TM from the spiral limbus altering the transmission pathway between the source of the DPOAEs and the point of measurement at the eardrum.

The loss of limbal attachment in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse causes a substantial increase in the CAP threshold, but does not affect the sharpness of neural tuning. Increased neural thresholds with preserved BM sensitivity have been described previously for the TectaY1870C/+ mouse in which the TM remains attached to the spiral limbus and the subtectorial space in the vicinity of the IHCs is much increased, but are accompanied by a broadening of the neural tuning curves despite the BM remaining sharply tuned. As a result of likely changes in the relative position of the TM and the hair cells caused by fixation and dehydration in the absence of firm attachment to the spiral limbus, it is not possible to determine whether or not the dimensions of the subtectorial space are altered in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse. Nonetheless, modeling studies (12) indicate only a small change (twofold, from 5 to 10 μm) in the dimensions of this space would severely reduce hydrodynamic input to the IHC bundle. Loss of limbal attachment may be sufficient to cause such a change, or reduce the pressure difference between the inner sulcus and the hair bundles of the OHCs (45) caused by organ of Corti motion, and therefore reduce the sensitivity of the IHCs without affecting neural tuning. Abrogation of pulsatile fluid motion caused by a rocking reticular lamina (10) seems an unlikely possibility, at least at CF, as the mouse cochlea operates at frequencies in excess of 3 kHz. Likewise it seems unlikely that the absence of Hensen's stripe leads to a loss in neural sensitivity, as it is only a prominent feature in the basal, high-frequency half of the murine cochlea and cannot be responsible for sensitivity in the low-frequency region of the CAP audiogram in the mouse.

The results also inform as to the cause of deafness in DFNB22 families. Three different recessive mutations in OTOA—a splice site mutation, a missense mutation, and a large genomic deletion—have been identified in Palestinian families as the cause of prelingual, sensorineural deafness (25, 46, 47). The degree of deafness of the affected individuals in two of these three families has been reported and has been described as being moderate to severe, i.e., similar or slightly more severe than the 35- to 55-dB hearing loss found in the OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse over the 8- to 55-kHz range. Although the exact consequences of the splice site and missense mutations are unknown, both are recessive and therefore likely to cause loss of function, as is also expected for the deletion that encompasses the first 19 of the 28 coding exons. The OtoaEGFP/EGFP mouse lacks expression of otoancorin and should be a faithful model for the recessive human mutations that have been identified thus far. The hearing loss in patients with recessive loss-of-function mutations in OTOA is therefore predicted to result from a failure in the excitation of the IHCs, and not a loss of cochlear amplification.

Methods

Full details of the methods used are provided in SI Methods. In brief, otoancorin KO mice (i.e., OtoaEGFP/EGFP) were produced from an ES cell line in which the first coding exon of Otoa had been replaced by EGFP using targeted mutagenesis. The morphology of the cochlea in WT, Otoa+/EGFP, and OtoaEGFP/EGFP mice was examined by light microscopy and SEM. For immunofluorescence microscopy, we used a rabbit serum raised to two nonoverlapping peptides located in the C-terminal half of otoancorin (25). For physiological analysis, sound stimuli were delivered and sound pressure near the tympanic membrane was monitored through a coupler placed within 1 mm of the tympanic membrane. Cochlear electrical responses were measured by using a glass micropipette placed at the round window. BM mechanical responses were recorded by using a self-mixing laser diode interferometer, with the laser beam focused on the BM through the transparent round window membrane. All procedures involving animals were performed in accordance with UK Home Office regulations with approval from the local ethics committee.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank James Hartley for technical support. This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Programme Grant 087737, Medical Research Council Programme Grant G0801693/2, Agence Nationale de Recherche Grant ANR-11 BSV5 01102 EARMEC, and European Research Council Grant ERC-2011-AdG 294570 (“Auditory Hair Bundle”).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. T.B.F. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1210159109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Davis H. A model for transducer action in the cochlea. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1965;30:181–190. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1965.030.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sellick PM, Russell IJ. The responses of inner hair cells to basilar membrane velocity during low frequency auditory stimulation in the guinea pig cochlea. Hear Res. 1980;2(3-4):439–445. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(80)90080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimura RS. Hairs of the cochlear sensory cells and their attachment to the tectorial membrane. Acta Otolaryngol. 1966;61(1):55–72. doi: 10.3109/00016486609127043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudspeth AJ, Corey DP. Sensitivity, polarity, and conductance change in the response of vertebrate hair cells to controlled mechanical stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74(6):2407–2411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.6.2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen JB. Cochlear micromechanics—a physical model of transduction. J Acoust Soc Am. 1980;68(6):1660–1670. doi: 10.1121/1.385198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zwislocki JJ. Theory of cochlear mechanics. Hear Res. 1980;2(3-4):171–182. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(80)90055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis H. An active process in cochlear mechanics. Hear Res. 1983;9(1):79–90. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(83)90136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dallos P, Billone MC, Durrant JD, Wang C, Raynor S. Cochlear inner and outer hair cells: Functional differences. Science. 1972;177(4046):356–358. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4046.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patuzzi RB, Yates GK. The low-frequency response of inner hair cells in the guinea pig cochlea: Implications for fluid coupling and resonance of the stereocilia. Hear Res. 1987;30(1):83–98. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nowotny M, Gummer AW. Nanomechanics of the subtectorial space caused by electromechanics of cochlear outer hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(7):2120–2125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511125103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman DM, Weiss TF. Hydrodynamic forces on hair bundles at high frequencies. Hear Res. 1990;48(1-2):31–36. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90197-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith ST, Chadwick RS. Simulation of the response of the inner hair cell stereocilia bundle to an acoustical stimulus. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3):e18161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legan PK, Rau A, Keen JN, Richardson GP. The mouse tectorins. Modular matrix proteins of the inner ear homologous to components of the sperm-egg adhesion system. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(13):8791–8801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen-Salmon M, El-Amraoui A, Leibovici M, Petit C. Otogelin: A glycoprotein specific to the acellular membranes of the inner ear. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(26):14450–14455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng J, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 16 interacts with alpha-tectorin and is mutated in autosomal dominant hearing loss (DFNA4) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(10):4218–4223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005842108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deans MR, Peterson JM, Wong GW. Mammalian Otolin: A multimeric glycoprotein specific to the inner ear that interacts with otoconial matrix protein Otoconin-90 and Cerebellin-1. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(9):e12765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verhoeven K, et al. Mutations in the human alpha-tectorin gene cause autosomal dominant non-syndromic hearing impairment. Nat Genet. 1998;19(1):60–62. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mustapha M, et al. An alpha-tectorin gene defect causes a newly identified autosomal recessive form of sensorineural pre-lingual non-syndromic deafness, DFNB21. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(3):409–412. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alasti F, et al. A novel TECTA mutation confirms the recognizable phenotype among autosomal recessive hearing impairment families. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(2):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hildebrand MS, et al. DFNA8/12 caused by TECTA mutations is the most identified subtype of nonsyndromic autosomal dominant hearing loss. Hum Mutat. 2011;32(7):825–834. doi: 10.1002/humu.21512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Legan PK, et al. A targeted deletion in alpha-tectorin reveals that the tectorial membrane is required for the gain and timing of cochlear feedback. Neuron. 2000;28(1):273–285. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Legan PK, et al. A deafness mutation isolates a second role for the tectorial membrane in hearing. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(8):1035–1042. doi: 10.1038/nn1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell IJ, et al. Sharpened cochlear tuning in a mouse with a genetically modified tectorial membrane. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(2):215–223. doi: 10.1038/nn1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lukashkin AN, Richardson GP, Russell IJ. Multiple roles for the tectorial membrane in the active cochlea. Hear Res. 2010;266(1-2):26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zwaenepoel I, et al. Otoancorin, an inner ear protein restricted to the interface between the apical surface of sensory epithelia and their overlying acellular gels, is defective in autosomal recessive deafness DFNB22. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(9):6240–6245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082515999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brownell WE, Manis PB, Zidanic M, Spirou GA. Acoustically evoked radial current densities in scala tympani. J Acoust Soc Am. 1983;74(3):792–800. doi: 10.1121/1.389866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zidanic M, Brownell WE. Fine structure of the intracochlear potential field. I. The silent current. Biophys J. 1990;57(6):1253–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82644-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zidanic M, Brownell WE. Fine structure of the intracochlear potential field. II. Tone-evoked waveforms and cochlear microphonics. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67(1):108–124. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell IJ, Cody AR, Richardson GP. The responses of inner and outer hair cells in the basal turn of the guinea-pig cochlea and in the mouse cochlea grown in vitro. Hear Res. 1986;22:199–216. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(86)90096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Müller M, von Hünerbein K, Hoidis S, Smolders JW. A physiological place-frequency map of the cochlea in the CBA/J mouse. Hear Res. 2005;202(1-2):63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dallos P, Cheatham MA. Compound action potential (AP) tuning curves. J Acoust Soc Am. 1976;59(3):591–597. doi: 10.1121/1.380903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrison RV, Prijs VF. Single cochlear fibre responses in guinea pigs with long-term endolymphatic hydrops. Hear Res. 1984;14(1):79–84. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sathyanarayana BK, Hahn Y, Patankar MS, Pastan I, Lee B. Mesothelin, Stereocilin, and Otoancorin are predicted to have superhelical structures with ARM-type repeats. BMC Struct Biol. 2009;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verpy E, et al. Stereocilin-deficient mice reveal the origin of cochlear waveform distortions. Nature. 2008;456(7219):255–258. doi: 10.1038/nature07380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dallos P. Some pending problems in cochlear mechanics. In: Gummer AW, editor. Biophysics of the cochlea: Molecules to models. Singapore: World Scientific; 2002. pp. 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geisler CD, Sang C. A cochlear model using feed-forward outer-hair-cell forces. Hear Res. 1995;86(1-2):132–146. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00064-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kronester-Frei A. Localization of the marginal zone of the tectorial membrane in situ, unfixed, and with in vivo-like ionic milieu. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1979;224(1-2):3–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00455217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson SL, Beurg M, Marcotti W, Fettiplace R. Prestin-driven cochlear amplification is not limited by the outer hair cell membrane time constant. Neuron. 2011;70(6):1143–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah DM, Freeman DM, Weiss TF. The osmotic response of the isolated, unfixed mouse tectorial membrane to isosmotic solutions: Effect of Na+, K+, and Ca2+ concentration. Hear Res. 1995;87(1-2):187–207. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00089-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xia A, et al. Deficient forward transduction and enhanced reverse transduction in the alpha tectorin C1509G human hearing loss mutation. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3(3-4):209–223. doi: 10.1242/dmm.004135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mammano F, Ashmore JF. A laser interferometer for sub-nanometre measurements in the cochlea. J Neurosci Methods. 1995;60(1-2):89–94. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)00223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russell IJ, Nilsen KE. The location of the cochlear amplifier: Spatial representation of a single tone on the guinea pig basilar membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(6):2660–2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen F, et al. A differentially amplified motion in the ear for near-threshold sound detection. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(6):770–774. doi: 10.1038/nn.2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu N, Zhao HB. Modulation of outer hair cell electromotility by cochlear supporting cells and gap junctions. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(11):e7923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steele CR, Puria S. Force on inner hair cell stereocilia. Int J Solids Struct. 2005;42:5885–5904. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walsh T, et al. Genomic analysis of a heterogeneous Mendelian phenotype: Multiple novel alleles for inherited hearing loss in the Palestinian population. Hum Genomics. 2006;2(4):203–211. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-2-4-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shahin H, et al. Five novel loci for inherited hearing loss mapped by SNP-based homozygosity profiles in Palestinian families. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:407–413. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.