Abstract

Cooperation via production of common goods is found in diverse life forms ranging from viruses to social animals. However, natural selection predicts a “tragedy of the commons”: Cheaters, benefiting from without producing costly common goods, are more fit than cooperators and should destroy cooperation. In an attempt to discover novel mechanisms of cheater control, we eliminated known ones using a yeast cooperator–cheater system engineered to supply or exploit essential nutrients. Surprisingly, although less fit than cheaters, cooperators quickly dominated a fraction of cocultures. Cooperators isolated from these cocultures were superior to the cheater isolates they had been cocultured with, even though these cheaters were superior to ancestral cooperators. Resequencing and phenotypic analyses revealed that evolved cooperators and cheaters all harbored mutations adaptive to the nutrient-limited cooperative environment, allowing growth at a much lower concentration of nutrient than their ancestors. Even after the initial round of adaptation, evolved cooperators still stochastically dominated cheaters derived from them. We propose the “adaptive race” model: If during adaptation to an environment, the fitness gain of cooperators exceeds that of cheaters by at least the fitness cost of cooperation, the tragedy of the commons can be averted. Although cooperators and cheaters sample from the same pool of adaptive mutations, this symmetry is soon broken: The best cooperators purge cheaters and continue to grow, whereas the best cheaters cause rapid self-extinction. We speculate that adaptation to changing environments may contribute to the persistence of cooperative systems before the appearance of more sophisticated mechanisms of cheater control.

Keywords: evolution of cooperation and cheating, experimental evolution, genetic hitchhiking, synthetic biology

The cooperative act of paying a cost to produce a publicly available good is a common biological phenomenon. Human volunteers contribute their time to build Wikipedia, which can be used by anyone with Internet access. Throughout the animal kingdom, alarm calls are produced by individuals to warn others of danger, even though producing the call makes the caller more conspicuous (1). Microbes excrete a plethora of costly compounds that can be used by the producers and their neighboring cells to acquire nutrients that are hard to obtain, access favorable environments, or improve antibiotic resistance (2, 3). In biological systems, publicly available goods are generally “common goods,” because consumption by one individual reduces their availability to others. “Cheaters” use the common good without paying a cost to produce it. Thus, because the common good is equally accessible to all members of a population, cheaters, introduced through migration or mutation, will be more fit than cooperators, increase in frequency, and eventually exhaust the common good, leading to the “tragedy of the commons” (4). For instance, although cooperative viruses produce diffusible shared proteins required for viral reproduction, selfish viruses synthesize less but sequester more of these proteins and thereby displace cooperative viruses, lowering overall infectivity (5). Cancers, a leading cause of death globally (6), cheat by exploiting the common good produced by normal cells that cooperate to form a functional human body.

Despite exploitation of common goods by naturally arising cheaters, cooperation persists (7–13). How does cooperation survive cheating? We first summarize mechanisms known to stabilize cooperation against cheating. We then describe our attempts to discover novel mechanisms of cheater control by excluding known ones from an engineered yeast cooperator–cheater system.

Frequently, through unexpected genetic or physical processes, what initially appear to be cheaters or common goods are not; thus, the tragedy of the commons does not apply. For instance, a gene required for cooperation can have pleiotropic effects, such that a cell defective in paying the cost of cooperation is also incapable of enjoying the cooperative benefit. In this case, cheaters will end up suffering a net fitness cost. This situation has been found to occur in the social amoeba Dictyostelium discodium. D. discodium responds to starvation by aggregating and forming a fruiting body. During fruiting body formation, some cells form a self-sacrificing, nonreproductive stalk, which lifts other cells that differentiate into reproductive spores. The gene encoding the receptor necessary for differentiation into stalk cells is also necessary for proper spore formation; thus, cheaters trying to avoid the stalk fate cannot become spores (14). Another possibility is that what appears to be a common good is actually partially privatized by its producer. For instance, the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae secretes invertase to hydrolyze the disaccharide sucrose into glucose and fructose, which can be metabolized more efficiently. These monosaccharides were initially thought to be strictly common goods (15), although it was later found that ∼1% are retained by the producing cell (16). Even such a seemingly insignificant level of privatization can allow cooperators to invade a population of cheaters (16, 17). This could explain the coexistence of invertase-producing cooperative cells with nonproducing cheating cells in wild populations (7). The benefits of privatization can only be realized when all cooperators produce and consume the same common good (homotypic cooperation). In mutualism, privatization is pointless because each individual requires a common good produced only by its partners.

Even if cheaters have a net fitness advantage over cooperators that produce true common goods, several mechanisms can avert the tragedy of the commons. First, when individuals interact through the production and/or consumption of inexpensive common goods in randomly formed groups that assemble and disassemble cyclically, as long as an increase in the availability of the common good leads to a less than proportional increase in the fitness of its consumers, a stable equilibrium between cooperators and cheaters is expected (18, 19). This “diminishing return” of the common good (16, 18) can account for the surprising observation that in the yeast invertase system, maximum group size is attained with a mixture of cheaters and cooperators: Cooperators produce more invertase than they can use, and cheaters convert this excess benefit into additional biomass (20). The cost-to-benefit ratio can be kept low if the common good is produced facultatively (i.e., only when needed), which is the case for most organisms, or if the durability of common goods is high, as found in siderophore production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (21, 22). Second, for cooperation based on scarce common goods, mechanisms of “positive assortment” that increase the frequency of interactions between cooperators (23) can facilitate the persistence of cooperation. Positive assortment can involve specifically directing benefits to other cooperators and excluding or punishing cheaters based on recognition or previous experience (24–26). This can occur even in organisms lacking nervous systems. For instance, microbes can achieve “recognition” through cell adhesion and chemical communication (27), and legumes “reward” and “punish” beneficial and cheating rhizobia, respectively (28, 29). Another mechanism of positive assortment is “population viscosity,” brought about by limited dispersal in spatially structured environments, which keeps cooperators clustered with their relatives in homotypic cooperation (24, 30–32), or with their partners in heterotypic cooperation (33). Thus, natural cooperative systems, whether homotypic or heterotypic, use many different mechanisms to mitigate the tragedy of the commons, allowing cooperation via common goods to be a successful evolutionary strategy.

Existing cooperative systems may have evolved for millions of years, and can now deploy mechanisms, such as pleiotropy, facultative production of common goods, and cheater recognition, to prevent destruction by cheaters. However, what about cheater control at the origins of these systems? A spatially structured environment can stabilize cooperation against cheating; however, under certain circumstances, it can hinder cooperation (34–36) through enhancing competition among cooperators (37–39). Furthermore, motile species may behave as if they were locally well-mixed even if they live in a spatially structured environment. To search for novel cheater-control mechanisms that might stabilize nascent cooperative systems, we extended a synthetically engineered model of cooperation (40) to include cheating (Fig. 1A). In this system, which is based on the yeast S. cerevisiae, cooperation occurs between the red-fluorescent  strain, which requires lysine (

strain, which requires lysine ( ) and provides adenine (

) and provides adenine ( ), and the yellow-fluorescent

), and the yellow-fluorescent  strain, which requires adenine (

strain, which requires adenine ( ) and provides lysine (

) and provides lysine ( ). The presence of both

). The presence of both  and

and  is necessary for growth in minimal media lacking adenine and lysine (SD) (40). The cheater is a cyan-fluorescent

is necessary for growth in minimal media lacking adenine and lysine (SD) (40). The cheater is a cyan-fluorescent  strain that requires lysine but does not provide any nutrients.

strain that requires lysine but does not provide any nutrients.

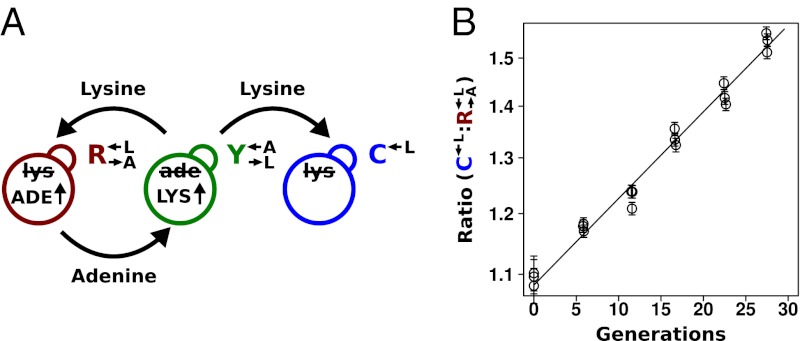

Fig. 1.

(A) Yeast model of cooperation and cheating. Our cooperative system is composed of two nonmating yeast strains. The red-fluorescent  strain (WY950) requires lysine and overproduces adenine, whereas the yellow-fluorescent

strain (WY950) requires lysine and overproduces adenine, whereas the yellow-fluorescent  strain (WY954) requires adenine and overproduces lysine. The cheater is a cyan-fluorescent

strain (WY954) requires adenine and overproduces lysine. The cheater is a cyan-fluorescent  strain (WY962) that requires lysine and does not overproduce adenine. (B) Cheaters have a fitness advantage over cooperators.

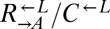

strain (WY962) that requires lysine and does not overproduce adenine. (B) Cheaters have a fitness advantage over cooperators.  and

and  strains were mixed and competed in SD supplemented with nonlimiting (164 μM) lysine. Cocultures were periodically diluted into fresh supplemented medium to maintain exponential growth. The ratio of

strains were mixed and competed in SD supplemented with nonlimiting (164 μM) lysine. Cocultures were periodically diluted into fresh supplemented medium to maintain exponential growth. The ratio of  to

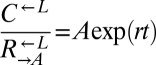

to  was determined using flow cytometry. The ratio was fit using weighted nonlinear least-squares regression to the form

was determined using flow cytometry. The ratio was fit using weighted nonlinear least-squares regression to the form  , where A is the initial ratio, r is the cheater growth rate minus the cooperator growth rate, and t is time in generations of

, where A is the initial ratio, r is the cheater growth rate minus the cooperator growth rate, and t is time in generations of  . Note the logarithmic y axis.

. Note the logarithmic y axis.  has a 1.8% (95% CI: 1.6–1.9%) advantage over

has a 1.8% (95% CI: 1.6–1.9%) advantage over  .

.

This system allows us to remove the mechanisms currently thought to avert the tragedy of the commons in a systematic manner. Engineering the cooperative interactions through mutations that constitutively overproduce metabolites eliminates the possibility of pleiotropy or facultative production. Using a two-partner heterotypic cooperative system renders privatization of common goods futile, because neither strain can directly use the common good it produces. After an initial period of asymmetrical nutrient release and cell death (40), our cooperative cocultures approach a stable doubling time (∼12 h) that is much slower than those of the corresponding monocultures supplemented with the necessary nutrient (∼2 h). Thus, common goods are very limited. Additionally, because cooperation is based on metabolic manipulations not found in the ancestor strain, it is unlikely that the cooperating partners could recognize one another or exclude the cheater. Because all strains are derived from S288C, which does not flocculate (41), growth in well-mixed liquid culture prevents spatial clustering. Using a simple, well-defined model (42) free of known mechanisms of cheater control, we hoped to discover new mechanisms that may stabilize cooperation against cheating.

Results

Cheaters Are Fitter Than Cooperators.

Many biosynthetic pathways are regulated by end-product feedback inhibition (e.g., 43, 44), which suggests that metabolite overproduction carries an evolutionarily significant cost. To quantify the cost of adenine overproduction in our cooperative yeast system, we competed  with

with  in SD supplemented with excess (164 μM) lysine and found that the latter carried a fitness advantage of 1.8% [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.6–1.9%; Fig. 1B]. In the absence of lysine, which occurs during the prolonged delay in lysine release by

in SD supplemented with excess (164 μM) lysine and found that the latter carried a fitness advantage of 1.8% [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.6–1.9%; Fig. 1B]. In the absence of lysine, which occurs during the prolonged delay in lysine release by  (40),

(40),  and

and  died at similar rates (95% CI of the difference in death rate: −0.003 to 0.0003 h−1; Fig. S1). In both conditions, the fitness difference between expressing CFP and DsRed is small. Given the overall fitness advantage of

died at similar rates (95% CI of the difference in death rate: −0.003 to 0.0003 h−1; Fig. S1). In both conditions, the fitness difference between expressing CFP and DsRed is small. Given the overall fitness advantage of  over

over  , the futility of privatization and paucity of common goods, and the lack of genetic mechanisms for cheater control, we predicted that in a well-mixed environment,

, the futility of privatization and paucity of common goods, and the lack of genetic mechanisms for cheater control, we predicted that in a well-mixed environment,  would increase in frequency and eventually destroy the cooperative system.

would increase in frequency and eventually destroy the cooperative system.

Cheaters Are Stochastically Purged from Cocultures.

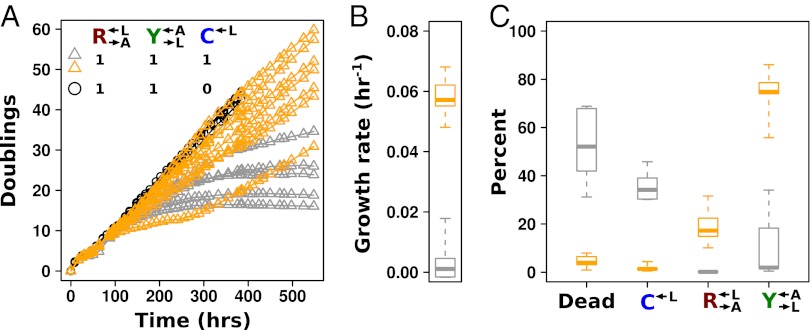

We experimentally tested the prediction of deterministic cheater dominance by mixing  ,

,  , and

, and  at a ratio of 1:1:1 in SD (Fig. 2). This master mix was split into replicate cocultures that were monitored for growth and diluted to ensure that nutrients other than adenine and lysine were never limiting (Materials and Methods). Surprisingly, within 50 generations, we observed a bifurcation in growth rates (Fig. 2B): Some cocultures were growing slowly or not at all (Fig. 2A, gray triangles), whereas others continued to grow (Fig. 2A, orange triangles) at rates very similar to cheater-free cocultures (Fig. 2A, black circles). At ∼450 h, we quantified the frequency of each population in each coculture using flow cytometry (Fig. 2C). The slow-growing cocultures (Fig. 2C, gray) contained mostly dead or dying cells that had lost membrane integrity, and therefore reacted with the nucleic acid dye TO-PRO-3. The remaining live cells were predominantly

at a ratio of 1:1:1 in SD (Fig. 2). This master mix was split into replicate cocultures that were monitored for growth and diluted to ensure that nutrients other than adenine and lysine were never limiting (Materials and Methods). Surprisingly, within 50 generations, we observed a bifurcation in growth rates (Fig. 2B): Some cocultures were growing slowly or not at all (Fig. 2A, gray triangles), whereas others continued to grow (Fig. 2A, orange triangles) at rates very similar to cheater-free cocultures (Fig. 2A, black circles). At ∼450 h, we quantified the frequency of each population in each coculture using flow cytometry (Fig. 2C). The slow-growing cocultures (Fig. 2C, gray) contained mostly dead or dying cells that had lost membrane integrity, and therefore reacted with the nucleic acid dye TO-PRO-3. The remaining live cells were predominantly  (“cheater-dominated”). Furthermore, cheater takeover took much less time than predicted: In fewer than 40 generations, the average

(“cheater-dominated”). Furthermore, cheater takeover took much less time than predicted: In fewer than 40 generations, the average  ratio was 280:1, as opposed to the 2:1 ratio predicted by the 1.8% fitness advantage of

ratio was 280:1, as opposed to the 2:1 ratio predicted by the 1.8% fitness advantage of  (Fig. 1B). Even more surprising were the fast-growing cocultures (Fig. 2C, orange). These cocultures contained mostly live

(Fig. 1B). Even more surprising were the fast-growing cocultures (Fig. 2C, orange). These cocultures contained mostly live  and

and  cells (“cooperator-dominated”), with an average

cells (“cooperator-dominated”), with an average  ratio of 16:1. We confirmed in subsequent experiments with a

ratio of 16:1. We confirmed in subsequent experiments with a  strain differentially marked with drug resistance that

strain differentially marked with drug resistance that  can be driven extinct in cooperator-dominated cocultures.

can be driven extinct in cooperator-dominated cocultures.

Fig. 2.

Stochastic cheater outcome in initially identical cooperator–cheater cocultures. (A and B) Distinct growth behavior in replicate cooperator–cheater cocultures. Exponential cultures of  ,

,  , and

, and  were washed to remove residual supplements and mixed as indicated to a final density of 4.2 × 105 cells/mL per strain. Twelve plus-cheater (triangles) and three minus-cheater (black circles) cocultures were propagated, with total cell density maintained in the subsaturation range of ∼106 cells/mL to 1.5 × 107 cells/mL by dilution into fresh SD when necessary. (B) After ∼400 h, the growth rates of plus-cheater cocultures were bimodally distributed into fast-growing (orange) and slow-growing (gray) groups. (C) Fast-growing cocultures are dominated by cooperators. At ∼450 h, the frequencies of dead cells reacting to the nucleic acid dye TOPRO-3 (Dead),

were washed to remove residual supplements and mixed as indicated to a final density of 4.2 × 105 cells/mL per strain. Twelve plus-cheater (triangles) and three minus-cheater (black circles) cocultures were propagated, with total cell density maintained in the subsaturation range of ∼106 cells/mL to 1.5 × 107 cells/mL by dilution into fresh SD when necessary. (B) After ∼400 h, the growth rates of plus-cheater cocultures were bimodally distributed into fast-growing (orange) and slow-growing (gray) groups. (C) Fast-growing cocultures are dominated by cooperators. At ∼450 h, the frequencies of dead cells reacting to the nucleic acid dye TOPRO-3 (Dead),  ,

,  , and

, and  cells in fast-growing (orange) and slow-growing (gray) cocultures were quantified using flow cytometry. Boxes extend from the first quartile to the third quartile of the data, “whiskers” extend to the most extreme observations, and the thick bar inside each box represents the median.

cells in fast-growing (orange) and slow-growing (gray) cocultures were quantified using flow cytometry. Boxes extend from the first quartile to the third quartile of the data, “whiskers” extend to the most extreme observations, and the thick bar inside each box represents the median.

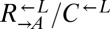

Extremely Fit Mutations Drive Stochastic Cooperator Dominance.

To understand what had caused rapid divergence in population growth and stochastic cheater outcomes, we investigated the detailed population dynamics of these cocultures by frequently sampling replicate cocultures using flow cytometry. All  and

and  populations, regardless of whether they eventually became cooperator- or cheater-dominated (Fig. 3A; solid or dashed lines, respectively), were nearly identical for the first ∼60 h of growth, suggesting that the vast majority of cells were behaving identically and, most likely, ancestrally. Afterward,

populations, regardless of whether they eventually became cooperator- or cheater-dominated (Fig. 3A; solid or dashed lines, respectively), were nearly identical for the first ∼60 h of growth, suggesting that the vast majority of cells were behaving identically and, most likely, ancestrally. Afterward,  and

and  diverged rapidly (Fig. 3A). On the other hand,

diverged rapidly (Fig. 3A). On the other hand,  from cooperator-dominated and cheater-dominated cocultures behaved identically until after the divergence between

from cooperator-dominated and cheater-dominated cocultures behaved identically until after the divergence between  and

and  (>80 h; Fig. 3A), suggesting that whatever was occurring in the

(>80 h; Fig. 3A), suggesting that whatever was occurring in the  and

and  populations preceded any changes in the

populations preceded any changes in the  population.

population.

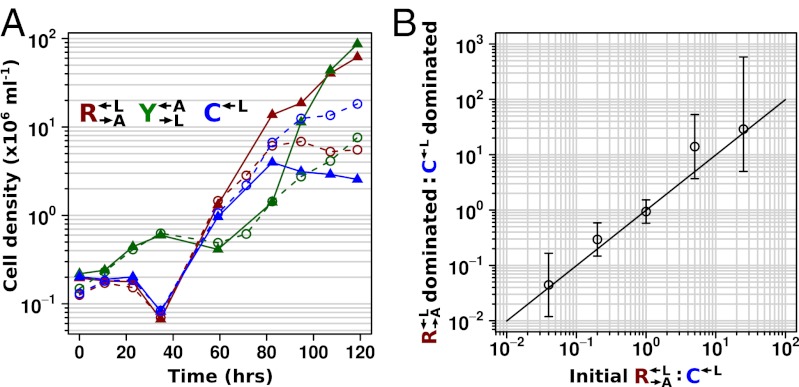

Fig. 3.

(A) Rapid divergence in the growth of cooperators and cheaters in cooperator-dominated and cheater-dominated cocultures. Cocultures were initiated at a density of 1.7 × 105 cells/mL per strain. Cell densities of the three subpopulations were measured by flow cytometry by adding fluorescent beads of a known concentration to each sample. After initially following similar trajectories, rapid divergence resulted in dominance of  cells (triangles connected by solid lines) or

cells (triangles connected by solid lines) or  cells (circles connected by dashed lines). A representative example of each class is shown. (B) Frequency of cooperator-dominated cocultures is determined by the initial frequency of cooperators. Cocultures were prepared as in A, except the initial density of

cells (circles connected by dashed lines). A representative example of each class is shown. (B) Frequency of cooperator-dominated cocultures is determined by the initial frequency of cooperators. Cocultures were prepared as in A, except the initial density of  or

or  was varied from 8.3 × 105 to 4.2 × 106 cells/mL per strain. Total initial population size influenced how quickly cocultures diverged but not the eventual frequency of cooperator-dominated cocultures. Error bars represent 95% CIs, assuming that the number of viable cocultures followed a binomial distribution with parameters n and p, where n is the total number of cocultures and p is the probability of being cooperator-dominated. The slope of the logistic regression fitting line,

was varied from 8.3 × 105 to 4.2 × 106 cells/mL per strain. Total initial population size influenced how quickly cocultures diverged but not the eventual frequency of cooperator-dominated cocultures. Error bars represent 95% CIs, assuming that the number of viable cocultures followed a binomial distribution with parameters n and p, where n is the total number of cocultures and p is the probability of being cooperator-dominated. The slope of the logistic regression fitting line,  , where c is the initial cooperator frequency, is 1.0 (95% CI: 0.7–1.3). This suggests that the odds of being a cooperator-dominated coculture are nearly equal to the initial proportion of

, where c is the initial cooperator frequency, is 1.0 (95% CI: 0.7–1.3). This suggests that the odds of being a cooperator-dominated coculture are nearly equal to the initial proportion of  . This occurs because, in our system, the fitness cost of cooperation is small.

. This occurs because, in our system, the fitness cost of cooperation is small.

One possible explanation for the rapid population divergence was the presence of variants with large fitness advantages relative to their ancestor. Consider the cooperator-dominated coculture (Fig. 3A, solid lines). If the  population obtained the most fit variant (

population obtained the most fit variant ( ) by the time of population divergence (∼60 h),

) by the time of population divergence (∼60 h),  must have proliferated enough to influence the growth kinetics of the red-fluorescent population visibly. To estimate the fitness advantage of

must have proliferated enough to influence the growth kinetics of the red-fluorescent population visibly. To estimate the fitness advantage of  over non-

over non- , we would need to know their relative abundance over time. We could not distinguish the two subpopulations directly from flow cytometry. However, because the

, we would need to know their relative abundance over time. We could not distinguish the two subpopulations directly from flow cytometry. However, because the  and

and  populations initially behaved similarly, and we expected both to be influenced by the presence of

populations initially behaved similarly, and we expected both to be influenced by the presence of  in a similar way, we assumed that the observed behavior of

in a similar way, we assumed that the observed behavior of  was similar to that of the non-

was similar to that of the non- portion of the red-fluorescent population. Thus, the population size of

portion of the red-fluorescent population. Thus, the population size of  could be approximated by the difference between the red-fluorescent and cyan-fluorescent populations. Assuming that all

could be approximated by the difference between the red-fluorescent and cyan-fluorescent populations. Assuming that all  cells were descendants of a single cell present at the beginning of the experiment, this cell must have doubled, on average, every ∼3.4 h to achieve its estimated abundance at 80 h, a large improvement from the ancestral average doubling time of ∼18.5 h (Materials and Methods). The same argument can be applied to the cheater-dominated coculture, which suggests that cooperation was destroyed by similar, highly adaptive variants that arose in the

cells were descendants of a single cell present at the beginning of the experiment, this cell must have doubled, on average, every ∼3.4 h to achieve its estimated abundance at 80 h, a large improvement from the ancestral average doubling time of ∼18.5 h (Materials and Methods). The same argument can be applied to the cheater-dominated coculture, which suggests that cooperation was destroyed by similar, highly adaptive variants that arose in the  population. These variants must not have been rare (>1 in 106 cells), because, otherwise, in many cocultures,

population. These variants must not have been rare (>1 in 106 cells), because, otherwise, in many cocultures,  and

and  would have failed to sample any variant and population divergence would have been slow.

would have failed to sample any variant and population divergence would have been slow.

and

and  thus appeared to be engaged in an “adaptive race” to obtain the most fit variant. If the same pool of variants was sampled by both populations, the final ratio of cooperator-dominated/cheater-dominated cocultures should be determined by the initial ratio of

thus appeared to be engaged in an “adaptive race” to obtain the most fit variant. If the same pool of variants was sampled by both populations, the final ratio of cooperator-dominated/cheater-dominated cocultures should be determined by the initial ratio of  . Furthermore, in our system, these two ratios should be approximately equal because the fitness advantage of

. Furthermore, in our system, these two ratios should be approximately equal because the fitness advantage of  over

over  is insignificant compared with the fitness gain of a successful variant. We tested this idea by setting up cocultures at different initial ratios of

is insignificant compared with the fitness gain of a successful variant. We tested this idea by setting up cocultures at different initial ratios of  (Fig. 3B;

(Fig. 3B;  was always 1:1). The slope relating the two ratios was 1.0 (95% CI: 0.7–1.3). Thus, consistent with our hypothesis that

was always 1:1). The slope relating the two ratios was 1.0 (95% CI: 0.7–1.3). Thus, consistent with our hypothesis that  and

and  were sampling from the same pool of variants, the frequency of being cooperator-dominated was determined by the initial frequency of

were sampling from the same pool of variants, the frequency of being cooperator-dominated was determined by the initial frequency of  .

.

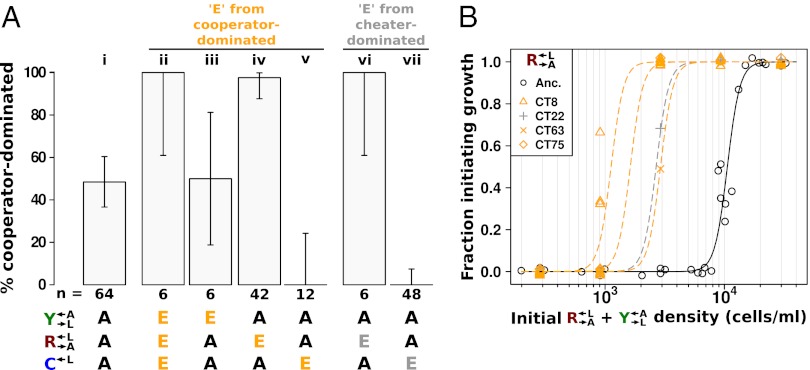

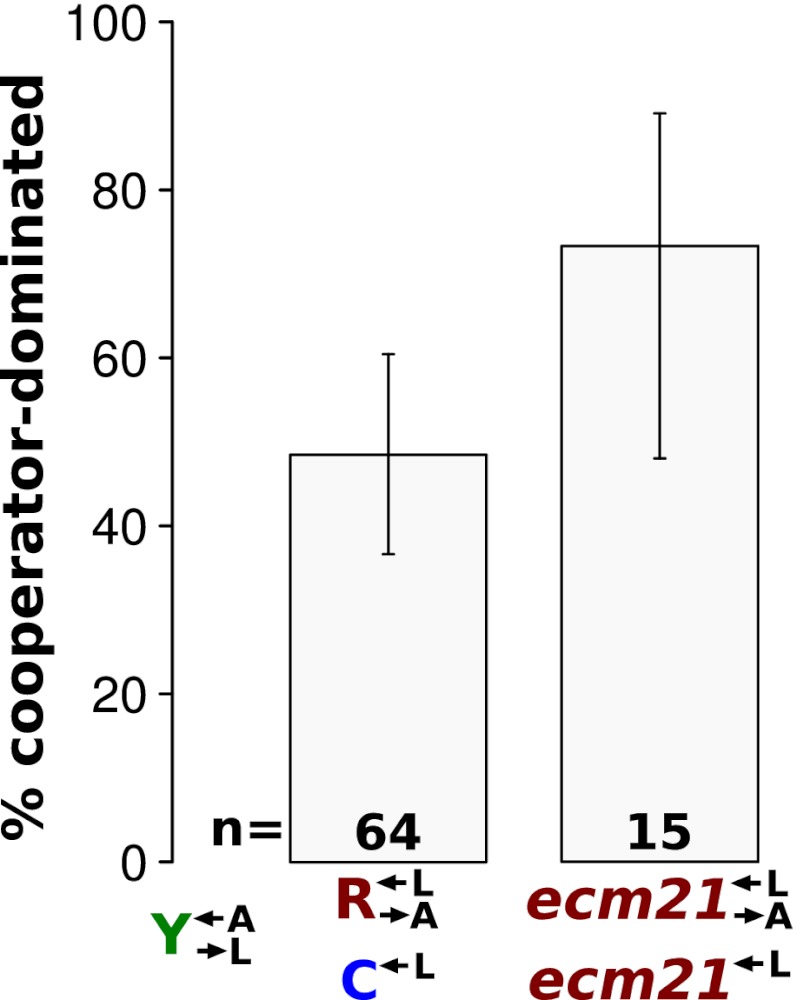

We next examined whether the improved fitness of these variants in the context of cooperation and cheating was a heritable phenotype. We isolated  ,

,  , and

, and  clones from a cooperator-dominated coculture; grew them in monoculture in SD supplemented with adenine or lysine; washed them free of supplements; and mixed them 1:1:1. Like the parental coculture, all six cocultures became cooperator-dominated (Fig. 4A, ii), which was significantly more than what was observed for 1:1:1 all-ancestor cocultures (Fig. 4A, i; 6 of 6 vs. 31 of 64 cooperator-dominated; Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.03). The isolated

clones from a cooperator-dominated coculture; grew them in monoculture in SD supplemented with adenine or lysine; washed them free of supplements; and mixed them 1:1:1. Like the parental coculture, all six cocultures became cooperator-dominated (Fig. 4A, ii), which was significantly more than what was observed for 1:1:1 all-ancestor cocultures (Fig. 4A, i; 6 of 6 vs. 31 of 64 cooperator-dominated; Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.03). The isolated  clone did not contribute to cooperator dominance (Fig. 4A, iii; 3 of 6 vs. 31 of 64 cooperator-dominated; Fisher’s exact test, P > 0.9). This is consistent with the idea that, short of partner-specific recognition, any changes in

clone did not contribute to cooperator dominance (Fig. 4A, iii; 3 of 6 vs. 31 of 64 cooperator-dominated; Fisher’s exact test, P > 0.9). This is consistent with the idea that, short of partner-specific recognition, any changes in  would affect

would affect  and

and  equally. On the other hand, we tested one

equally. On the other hand, we tested one  isolate from each of seven independent cooperator-dominated cocultures and found that they dominated ancestral

isolate from each of seven independent cooperator-dominated cocultures and found that they dominated ancestral  in a nearly deterministic fashion (Fig. 4A, iv; 41 of 42 vs. 31 of 64 cooperator-dominated; Fisher’s exact test, P < 3 × 10−8). We then tested five isolates of

in a nearly deterministic fashion (Fig. 4A, iv; 41 of 42 vs. 31 of 64 cooperator-dominated; Fisher’s exact test, P < 3 × 10−8). We then tested five isolates of  from three independent cheater-dominated cocultures and found that they deterministically dominated ancestral cooperators (Fig. 4A, vii; 0 of 48 vs. 31 of 64 cooperator-dominated; Fisher’s exact test P < 10−9). Thus, changes occurring in

from three independent cheater-dominated cocultures and found that they deterministically dominated ancestral cooperators (Fig. 4A, vii; 0 of 48 vs. 31 of 64 cooperator-dominated; Fisher’s exact test P < 10−9). Thus, changes occurring in  and

and  were heritable and sufficient for dominating ancestral

were heritable and sufficient for dominating ancestral  and

and  , respectively.

, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Evolved cooperators and cheaters are superior to ancestors. (A) Improved cooperation and cheating are heritable and occur in both “winning” and “losing” strains. Cocultures consisting of ancestral strains (A) and strains isolated from cooperator-dominated (orange) or cheater-dominated (gray) cocultures (E) were formed as indicated at equal initial densities. Percentages of cooperator-dominated cocultures were measured from replicate cocultures whose numbers (n) are indicated. Error bars represent the 95% CI calculated as in Fig. 3B. (B) Improved  can initiate cooperation at lower densities than its ancestor. Ancestral

can initiate cooperation at lower densities than its ancestor. Ancestral  (black) and

(black) and  isolated from cooperator-dominated (orange) and cheater-dominated (gray) cocultures were mixed 1:1 with ancestral

isolated from cooperator-dominated (orange) and cheater-dominated (gray) cocultures were mixed 1:1 with ancestral  and serially diluted into a microtiter plate. After 1 mo at 30 °C, wells showing visible growth were scored. Data are jittered slightly in the vertical direction to aid visualization.

and serially diluted into a microtiter plate. After 1 mo at 30 °C, wells showing visible growth were scored. Data are jittered slightly in the vertical direction to aid visualization.

If  and

and  sampled from the same pool of mutations during the adaptive race, then even the “losing” types (i.e.,

sampled from the same pool of mutations during the adaptive race, then even the “losing” types (i.e.,  from cheater-dominated and

from cheater-dominated and  from cooperator-dominated cocultures) may nevertheless have improved relative to their respective ancestors. We tested two losing

from cooperator-dominated cocultures) may nevertheless have improved relative to their respective ancestors. We tested two losing  isolates from cooperator-dominated cocultures, and both were significantly better than ancestral

isolates from cooperator-dominated cocultures, and both were significantly better than ancestral  at dominating ancestral

at dominating ancestral  (Fig. 4A, v; 0 of 12 vs. 31 of 64 cooperator-dominated; Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.002). We tested one losing

(Fig. 4A, v; 0 of 12 vs. 31 of 64 cooperator-dominated; Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.002). We tested one losing  isolate, and it was better than ancestral

isolate, and it was better than ancestral  at dominating ancestral

at dominating ancestral  (Fig. 4A, vi; 6 of 6 vs. 31 of 64 cooperator-dominated; Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.03).

(Fig. 4A, vi; 6 of 6 vs. 31 of 64 cooperator-dominated; Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.03).

In addition to dominating ancestral  and the evolved

and the evolved  that they had raced against, evolved

that they had raced against, evolved  strains improved in the sense that they lowered the minimal cell density required to initiate a viable cooperative coculture (40). We tested a panel of six

strains improved in the sense that they lowered the minimal cell density required to initiate a viable cooperative coculture (40). We tested a panel of six  strains isolated from cooperator-dominated or cheater-dominated cocultures. We mixed each isolate 1:1 with ancestral

strains isolated from cooperator-dominated or cheater-dominated cocultures. We mixed each isolate 1:1 with ancestral  and serially diluted each coculture into SD. Compared with ancestral cocultures, cocultures initiated with evolved

and serially diluted each coculture into SD. Compared with ancestral cocultures, cocultures initiated with evolved  required less than one-third of the initial cell density to achieve growth in 50% of replicate cocultures (Fig. 4B). Cocultures initiated with evolved

required less than one-third of the initial cell density to achieve growth in 50% of replicate cocultures (Fig. 4B). Cocultures initiated with evolved  showed a similar degree of improvement (Fig. S2).

showed a similar degree of improvement (Fig. S2).

The Adaptive Race Is Fueled by Mutations in a Small Set of Genes Involved in Nutrient Transport.

We used whole-genome resequencing to identify the mutations underlying the rapid evolution in cooperators and cheaters. Some strains contained only one unambiguous, high-quality, nonsynonymous SNP. These mutations defined a set of genes, exactly one of which was mutated in every sequenced strain that contained any nonsynonymous mutations. We therefore reasoned that mutations in these genes were responsible for improvements in cooperation and cheating relative to the ancestor strains. All alleles of these genes and the strains that contain them are reported in Table 1 (a complete list of sequenced strains and their SNPs can be found in Dataset S1). Of the 17 unique alleles found, ECM21 and DOA4 had 6 each, accounting for 70% of the total. A simple estimate based on the Poisson distribution suggests that we found ∼97% of the genes responsible for the initial fitness increase. The small number of genes could still allow for rapid divergence between populations if each of the many alleles conferred a different fitness gain, because it would be unlikely for two populations to sample the same allele of the same gene.

Table 1.

Mutations potentially sufficient for the observed large fitness advantage in the nutrient-limited cooperative environment

| Gene | Allele | Strain | Cell type | Coculture dominated by | Mutant frequency |

| ECM21 | Q143* | CT22 |  |

Cheater | 0.35 |

| E268* | CT11† |  |

Cheater | ||

| S300* | CT78 |  |

Cooperator | ||

| L475R | CT82 |  |

Cheater | ||

| Q544* | CT65†, CT75† |  |

Cooperator | ||

| L780* | CT63† |  |

Cooperator | ||

| DOA4 | D213G | CT60 |  |

Cheater | 0.35 |

| P235L | CT69, CT106 |  |

Cheater | ||

| A643P | CT12 |  |

Cheater | ||

| Q660K | CT7† |  |

Cooperator | ||

| Ins ‘A’ → C735* | CT17 |  |

Cooperator | ||

| Y916* | CT61† |  |

Cooperator | ||

| RSP5 | L131W | CT8 |  |

Cooperator | 0.12 |

| N746K | CT110† |  |

Cheater | ||

| BRO1 | Q434* | CT83† |  |

Cheater | 0.12 |

| S673* | CT57† |  |

Cheater | ||

| LYP1 | D583N | CT10 |  |

Cheater | 0.06 |

Ins, indicates an insertion.

*Indicates STOP codon.

†Indicates the presence of additional high-quality SNPs in this strain.

Most of the identified genes suggested that evolved  and

and  enhanced import of the limiting lysine provided by

enhanced import of the limiting lysine provided by  by decreasing transporter turnover. Ecm21p is an arrestin-like adaptor protein that allows the E3 ubiquitin ligase Rsp5p to ubiquitinate and degrade the high-affinity lysine permease Lyp1p in response to stress (45). All but one of the ECM21 mutations introduced a premature stop codon before the PY-motif necessary for interaction with Rsp5p (45). Doa4p is a deubiquitination protein required to maintain free ubiquitin pools (46) and is specifically implicated in deubiquitination of plasma membrane proteins (47). Significantly, Doa4p represses expression of the general amino acid permease Gap1p (48), which can import lysine (49, 50). Less frequently observed were mutations in RSP5 itself; in BRO1, which is necessary for the function of Doa4p by recruiting it to endosomes (51); and in the high-affinity lysine permease gene LYP1 (50, 52).

by decreasing transporter turnover. Ecm21p is an arrestin-like adaptor protein that allows the E3 ubiquitin ligase Rsp5p to ubiquitinate and degrade the high-affinity lysine permease Lyp1p in response to stress (45). All but one of the ECM21 mutations introduced a premature stop codon before the PY-motif necessary for interaction with Rsp5p (45). Doa4p is a deubiquitination protein required to maintain free ubiquitin pools (46) and is specifically implicated in deubiquitination of plasma membrane proteins (47). Significantly, Doa4p represses expression of the general amino acid permease Gap1p (48), which can import lysine (49, 50). Less frequently observed were mutations in RSP5 itself; in BRO1, which is necessary for the function of Doa4p by recruiting it to endosomes (51); and in the high-affinity lysine permease gene LYP1 (50, 52).

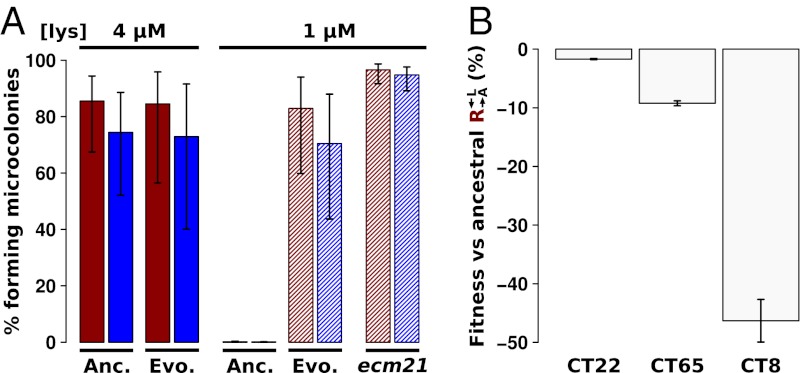

To test whether nutrient transport was enhanced in evolved strains, we compared the ability of evolved and ancestral cells to grow into microcolonies (defined as >5 cells) under limiting concentrations of lysine. Although ancestral  and

and  could grow on 4 μM but not 1 μM lysine (Fig. 5A, Anc.), every evolved

could grow on 4 μM but not 1 μM lysine (Fig. 5A, Anc.), every evolved  and

and  isolate could grow as well on 1 μM lysine as they did on 4 μM lysine (Fig. 5A, Evo.). This improvement came at a cost, because almost all the evolved cooperators and cheaters grew slower in nonlimiting lysine than their ancestors (Fig. 5B), which is consistent with their low frequency at the start of our experiments. Thus, adaptation to the nutrient-limited cooperative environment involved a tradeoff in fitness in nonlimiting nutrient.

isolate could grow as well on 1 μM lysine as they did on 4 μM lysine (Fig. 5A, Evo.). This improvement came at a cost, because almost all the evolved cooperators and cheaters grew slower in nonlimiting lysine than their ancestors (Fig. 5B), which is consistent with their low frequency at the start of our experiments. Thus, adaptation to the nutrient-limited cooperative environment involved a tradeoff in fitness in nonlimiting nutrient.

Fig. 5.

Evolved cooperators and cheaters show a tradeoff between the ability to grow at low-lysine concentrations and the maximum growth rate achieved at high-lysine concentrations. (A) Evolved strains grow better at low-lysine concentrations than their ancestors. Exponentially growing ancestral (Anc.) or evolved (Evo.) cooperator (red) and cheater (blue) strains were washed free of lysine and starved for 16–20 h to deplete vacuolar storage of lysine. Cells were plated at ∼200 cells/cm2 onto minimal medium agar containing 4 μM (solid bar) or 1 μM (shaded bar) lysine. After 1–3 d, clusters of >5 cells were counted as microcolonies. Percentages and SEs were estimated using a generalized linear mixed-effect model (Materials and Methods). The ecm21Δ143 allele from evolved cooperator CT22 was cloned into the ancestral cooperator and cheater strains (Materials and Methods), and their growth on low-lysine plates was measured (ecm21). The percentage is based on scoring >100 cells. Error bars indicate the 95% CI, assuming a binomial distribution with parameters n and p, as in Fig. 3B. (B) Evolved cooperators have lower growth rates than their ancestors in nonlimiting lysine. Relative fitness compared with ancestral  was measured for CT22 and CT65 through direct competition and calculated for CT8 using monoculture growth rates.

was measured for CT22 and CT65 through direct competition and calculated for CT8 using monoculture growth rates.

To confirm that the observed mutations were sufficient to improve growth on limiting lysine, we replaced full-length ECM21 in ancestral  and

and  with the truncated version found in the evolved

with the truncated version found in the evolved  strain CT22 (Table 1). Indeed, nearly 100% of these cells were able to grow on media containing 1 μM lysine (Fig. 5A, ecm21).

strain CT22 (Table 1). Indeed, nearly 100% of these cells were able to grow on media containing 1 μM lysine (Fig. 5A, ecm21).

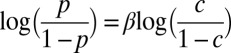

Improved Cooperators Can Stochastically Defeat Newly Arising Cheaters.

If during adaptation to the nutrient-limited cooperative environment, the maximum fitness gain of cooperators exceeds that of cheaters by at least the cost of cooperation, cooperators will win the race (Fig. 2A), and eventually purge the inferior cheaters. However, a mutation could turn an evolved cooperator into a cheater, which would now be as well-adapted to the nutrient-limited cooperative environment as the cooperators, and would therefore rise in frequency. Because successive fitness gains during adaptation to the same environment are expected to decrease over time (53), we tested whether evolved cooperators could stochastically dominate otherwise isogenic cheaters during a subsequent round of the adaptive race. We chose two improved cooperator strains (CT22 and CT75; Table 1) carrying different truncation alleles of ECM21 and derived, via allele replacement, matched cooperators and cheaters marked by different drug resistances (2 independent pairs from CT22 and 1 pair from CT75; Table 1 and Table S1). As a control, similarly matched cooperators and cheaters were derived from ancestral  (Table S1, WY1356-WY1359).

(Table S1, WY1356-WY1359).

As before,  and

and  pairs were mixed with ancestral

pairs were mixed with ancestral  at a ratio of 1:1:1. The frequencies of each cell type were periodically measured by plating onto media containing the appropriate antibiotic. As expected, the derived ancestral cocultures showed stochastic cooperator dominance (2 of 12 were cooperator-dominated). Of the cocultures derived from the two ecm21 alleles (Fig. 6,

at a ratio of 1:1:1. The frequencies of each cell type were periodically measured by plating onto media containing the appropriate antibiotic. As expected, the derived ancestral cocultures showed stochastic cooperator dominance (2 of 12 were cooperator-dominated). Of the cocultures derived from the two ecm21 alleles (Fig. 6,  and

and  ), 11 were cooperator-dominated, 4 were cheater-dominated, and 2 were indeterminate. Thus, even after cooperators had obtained major fitness improvements in the cooperative environment, a fraction of them were able to fend off cheaters that were just as well-adapted.

), 11 were cooperator-dominated, 4 were cheater-dominated, and 2 were indeterminate. Thus, even after cooperators had obtained major fitness improvements in the cooperative environment, a fraction of them were able to fend off cheaters that were just as well-adapted.

Fig. 6.

Stochastic cheater purging observed in cocultures composed of cooperators and cheaters previously exposed to the cooperative environment. We replaced the adenine overproduction allele of ADE4 (PUR6) in two evolved  strains containing truncation alleles of ECM21 (CT22 and CT75; Table 1) with PUR6 or WT ADE4 marked with different antibiotic resistances. Cocultures were initiated at 1:1:1. Frequencies of cell types were periodically determined by plating onto media containing the appropriate antibiotic. A coculture was considered “cooperator-dominated” if the ratio of

strains containing truncation alleles of ECM21 (CT22 and CT75; Table 1) with PUR6 or WT ADE4 marked with different antibiotic resistances. Cocultures were initiated at 1:1:1. Frequencies of cell types were periodically determined by plating onto media containing the appropriate antibiotic. A coculture was considered “cooperator-dominated” if the ratio of  to

to  was >100, or if the frequency of

was >100, or if the frequency of  fell below 1% of its initial frequency. It was considered “cheater-dominated” if the ratio of

fell below 1% of its initial frequency. It was considered “cheater-dominated” if the ratio of  to

to  was >100, or if the frequency of

was >100, or if the frequency of  fell below 1% of its initial frequency. It was considered “indeterminate” if none of these conditions were satisfied after ∼2,000 h of propagation. Indeterminate cocultures were excluded from the analysis. Because results across pairs were not significantly different from one another, the data were combined and are presented as

fell below 1% of its initial frequency. It was considered “indeterminate” if none of these conditions were satisfied after ∼2,000 h of propagation. Indeterminate cocultures were excluded from the analysis. Because results across pairs were not significantly different from one another, the data were combined and are presented as  and

and  . Error bars are the 95% CIs calculated as in Fig. 3B.

. Error bars are the 95% CIs calculated as in Fig. 3B.

Discussion

To uncover novel mechanisms that allow cooperation based on the production of common goods to survive cheating, we examined an engineered cooperative system that bypasses known mechanisms of cheater control. After adding cheaters, we expected slow but deterministic cheater takeover. Instead, identically initiated cocultures showed rapid population divergence: Whereas cheaters rapidly destroyed cooperation in some cocultures, cooperators rapidly displaced cheaters in other cocultures. We determined that this process was an adaptive race between cheaters and cooperators that was driven by strong selection for improved growth in the novel, nutrient-limited cooperative environment.

The race between cooperators and cheaters to adapt to a new environment can eventually favor cooperation, despite the initial fitness advantage of cheaters. As has been shown theoretically, if the frequency of recombination is negligible and if the fitness gain of the most adaptive mutation in cooperators exceeds that of cheaters by at least the fitness cost of cooperation, the cooperative trait can “hitchhike” on environmental adaptation and rise to high frequency (54–56). Otherwise, cheaters dominate. Thus, the probability of either type eventually dominating a coculture is related to its initial abundance in the population (Fig. 3B), because a larger population is more likely to sample better mutations. However, this initial symmetry is quickly broken: If cheaters dominate, the cooperative system will collapse (Fig. 2, gray) because the common good necessary for survival is no longer produced in sufficient quantities. In fact, the better the mutation obtained by cheaters, the sooner self-extinction will occur. On the other hand, if cooperators dominate, they continue to produce the common good and proliferate (Fig. 2, orange). These cooperators have improved their ability to initiate cooperation (Fig. 4B) and are able to defeat evolved cheaters that are superior to the ancestral cheater (Fig. 4A). While proliferating, cooperators can potentially acquire further beneficial mutations (57).

Two factors can synergize with the adaptive race to stabilize cooperation. First, different types of environmental change can provide different opportunities for adaptation. Improved cooperators that have survived one round of the adaptive race will eventually generate cheating mutants. Initially, the small population size of these cheating mutants makes them vulnerable to extinction by genetic drift and less likely to acquire the best mutation during subsequent rounds of the adaptive race. Eventually, however, cheaters will crash the cooperative system if the environment remains constant long enough. This is because the magnitude of possible fitness gains from subsequent adaptations will diminish over time (53). However, other environmental changes in, for example, temperature or osmolarity will select for distinct mutations that confer large fitness gains, triggering another adaptive race. Second, if individuals can migrate between spatially separated populations, “Simpson’s paradox” allows cooperators to dominate globally even though cheaters grow faster in each population. This can occur even when the population structure is periodically destroyed by global mixing (58). The only requirement is sufficiently variable cheater frequency between groups, which can be achieved through dilution (58), or through mutations obtained during an adaptive race. Thus, in conjunction with spatially structured environments that change in different ways, two unavoidable realities of nature, the adaptive race “buys time” for a cooperative system to acquire additional mutations that may result in more reliable mechanisms of cheater tolerance, such as partner recognition.

Our cooperative system was engineered to cooperate in a manner completely foreign to its ancestor; thus, it is pertinent to consider whether the adaptive race occurs in more natural systems. We consider two examples in natural microbial cooperative communities in which the adaptive race may have operated. The first example involves the social bacterium Myxococcus xanthus, members of which, when starved, exchange developmental signals, aggregate, and differentiate to form a fruiting body. During this process, a majority of cells die, whereas the remaining cells become tough spores (59). This provides an opportunity for a strain to cheat by disproportionately forming spores when mixed with another strain (60). One cheater strain that could not form spores on its own repeatedly rose to a high frequency when mixed with a cooperative strain and drove the entire system to very low population sizes (60). Reminiscent of our system, some of the replicate cocultures suffered complete collapse, whereas the remaining cocultures emerged cheater-free. If not solely due to drift, we suspect that this stochastic cheater outcome may be the result of an adaptive race similar to what we report here. This could occur if the cheater created a novel environment unfamiliar to the cooperative ancestor strain. If the emerging cooperators demonstrate an improved ability to defeat ancestral cheaters, sequencing evolved cooperators might reveal the type of novel environment imposed by cheaters, as well as the mechanisms deployed to adapt to it.

A second example of a potential adaptive race was recently shown in the siderophore-producing bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens (54). During iron limitation, P. fluorescens produces and releases iron-chelating siderophores that can be taken up by any nearby individual. When nonproducing cheaters, which have a large fitness advantage over siderophore-producing cooperators, were mixed with cooperators in an iron-limited environment, cheaters introduced at low frequency failed to invade (61). The authors proposed that this occurred because the numerically dominant cooperators had a greater chance of obtaining a high-fitness mutation adaptive to iron limitation that could sweep through the population. However, the actual mechanisms were not determined. This implies that although P. fluorescens must have experienced similar types of iron limitation throughout its evolutionary history, as evidenced by the very existence of siderophore production, the experimentally imposed iron limitation was still sufficiently “novel” to elicit an adaptive race. This supports our experimental finding that the environment does not need to be completely novel for the adaptive race to occur (Fig. 6).

Similar genetic hitchhiking in a not-so-novel environment was recently observed outside the context of cooperation. In an experiment initially designed to track deterministic takeover of sterile yeast mutants (which have greater fitness than nonsterile cells), the researchers observed complex patterns consistent with the rise of multiple nonsterile mutants with greater fitness than the sterile mutants (62). Importantly, this occurred in rich media thought to impose minimal selective pressure. These examples illustrate that the conditions necessary to initiate the adaptive race may be met more frequently than is currently assumed.

In summary, by using an engineered cooperating–cheating yeast system to bypass all known cheater-control mechanisms, we discovered that the adaptive race allowed cooperators to defeat cheaters stochastically. This simple mechanism requires low rates of recombination and can be triggered by any environment in which adaptation offers fitness gains greater than the cost of cooperation. Experimental evidence from naturally occurring cooperative systems suggests that these conditions may be met even when the environment is not completely novel (60, 61). Because adaptation to a changing environment is the norm in biology, we propose that the adaptive race between cooperators and cheaters, especially in spatially structured populations, is a fundamental mechanism for cooperative systems to survive the perpetual onslaught of cheaters.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Cell Culture.

All strains were derived from the BY designer deletion strains of the S288C background (63) and created essentially as described by Shou et al. (40). A list of constructed strains used in this study is provided in Table S1. To derive cooperating and cheating strains from a parent strain, DNA fragments PCR-amplified off a cassette containing either WT ADE4 and resistance to Hygromycin B (hph; WSB150) or an ADE4 overproduction allele (PUR6) and resistance to ClonNAT (nat; WSB151) were transformed into the parent strain. The primers contained regions homologous to the site of integration. Transformants were selected on media containing the appropriate antibiotic. The presence of ADE4 or PUR6 in the lysine-auxotrophic parent strain was determined by patching a small amount of transformant onto SD + lysine plates prespread with ade8 diploid cells and cut into individual squares. Overproduction of adenine resulted in adenine release and visible growth of ade8 cells into satellite colonies, whereas strains with ADE4 did not. By replacing ECM21 after the 142nd amino acid with DNA fragments PCR-amplified off an hph-containing cassette (WSB117), ecm21Δ143 strains were created.

Cells were grown at 30 °C in the rich medium YPD [1% (wt/vol) Bacto-yeast extract, 2% (wt/vol) Bacto-peptone, 2% (wt/vol) dextrose, 2% (wt/vol) Bacto-agar] or the minimal medium SD [0.67% (wt/vol) Difco Yeast Nitrogen Base without amino acids, 2% (wt/vol) dextrose] with or without supplemented amino acids, as necessary (64). To prepare for use, strains were struck from the freezer and grown on YPD plates at 30 °C for 2–3 d. An individual colony was picked and grown at 30 °C in liquid YPD until saturated (1–3 d). Unless otherwise indicated, strains were diluted >1:1,000 into SD + lysine or adenine and grown for ∼16 h to exponential phase (∼2 × 106–4 × 106 cells/mL) before being assayed.

Calculation of Average Doubling Times.

The average doubling times of  and

and  were calculated using the formula

were calculated using the formula  , where

, where  is time in hours,

is time in hours,  is the population size at time 0, and

is the population size at time 0, and  is the population size at time

is the population size at time  .

.

Competition Assays.

To measure the fitness difference between cooperators and cheaters (Fig. 1B), exponentially growing cells were washed and resuspended in SD, diluted to 1.7 × 105 cells/mL into SD (for death competition) or SD + 164 μM lysine (for growth competition) in triplicate, and incubated at 30 °C on a rotator. Growing cocultures were periodically diluted to maintain exponential growth, while keeping population size above 3 × 104 cells per strain. Ratios of the competing strains were determined by flow cytometry periodically. The relationship between the  ratio and time in generations of

ratio and time in generations of  (t) was fit to the form

(t) was fit to the form  using the method of weighted nonlinear least-squares, where A is the initial ratio and r is the difference in Malthusian parameters between

using the method of weighted nonlinear least-squares, where A is the initial ratio and r is the difference in Malthusian parameters between  and

and  . Because the growth rate of any population (

. Because the growth rate of any population ( here) is

here) is  per generation by definition, percent fitness advantage with respect to

per generation by definition, percent fitness advantage with respect to  was calculated as

was calculated as  . To determine fitness differences between

. To determine fitness differences between  and its evolved descendants (Fig. 5B), which were all red-fluorescent, an otherwise isogenic yellow-fluorescent

and its evolved descendants (Fig. 5B), which were all red-fluorescent, an otherwise isogenic yellow-fluorescent  strain was competed against each strain. The difference in fitness between

strain was competed against each strain. The difference in fitness between  and

and  (0.1%) was an order of magnitude less than the difference in fitness between

(0.1%) was an order of magnitude less than the difference in fitness between  and the fastest growing evolved strain (1.7%, CT22).

and the fastest growing evolved strain (1.7%, CT22).

Flow Cytometry.

Population compositions were measured by flow cytometry using a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) or DxP10 (Cytek) with three lasers (405 nm, 488 nm, and 633 nm). If necessary, fluorescent beads of known concentration were added to determine cell densities. Data analyses were performed using FloJo (TreeStar) or custom software written in R (65) using the Bioconductor (66) packages flowCore (67), flowMeans (68), and flowViz (69).

Coculture Growth and Assay of Population Compositions.

Exponentially growing cells were washed in SD and counted using a CoulterCounter Z2 (Beckman Coulter) or by flow cytometry. After counting, cells were diluted into SD and mixed. Then, 3-mL aliquots were put in 13-mm tubes and cultured on a rotator at 30 °C. OD600 was monitored at least once a day using a Gensys 20 (Thermo Spectronic), and population compositions were determined by flow cytometry. To estimate densities and ratios for the ecm21 strains (Fig. 6), cocultures were sampled into a microtiter plate and serially diluted in 10-fold steps from 1- to 10−4-fold using a multichannel pipette; spotted onto agar plates containing YPD, YPD + clonNAT (100 μg/mL), and YPD + Hygromycin B (200 μg/mL); and incubated at 30 °C for up to 7 d. Colony counts were used to calculate population sizes of the entire coculture (YPD),  (YPD + clonNAT), and

(YPD + clonNAT), and  (YPD + Hygromycin B).

(YPD + Hygromycin B).

Viability Assay.

Exponentially growing cells were washed free of supplements. Ancestral  and ancestral and evolved

and ancestral and evolved  strains were mixed 1:1 and serially diluted in a deep multiwell trough (∼10 mL per well) (Fig. 4B). Six or twelve 200-μL aliquots of each prepared density were transferred into wells of a microtiter plate using a multichannel pipette, which were then sealed using parafilm and placed in a 30 °C incubator in moisturized Tupperware bins for 1 mo. Visible growth by eye was considered successful initiation of cooperation. Data were analyzed using a generalized linear model with a binomial link function. Strain and the logarithm of cell density were fixed effects.

strains were mixed 1:1 and serially diluted in a deep multiwell trough (∼10 mL per well) (Fig. 4B). Six or twelve 200-μL aliquots of each prepared density were transferred into wells of a microtiter plate using a multichannel pipette, which were then sealed using parafilm and placed in a 30 °C incubator in moisturized Tupperware bins for 1 mo. Visible growth by eye was considered successful initiation of cooperation. Data were analyzed using a generalized linear model with a binomial link function. Strain and the logarithm of cell density were fixed effects.

Microcolony Growth Assay.

Exponentially growing cells were washed and resuspended in SD, and then diluted to ensure that they would remain at low density after residual growth. After starvation in SD for 16–20 h, cell density was estimated by OD600, diluted to ∼104 cells/mL, and plated onto SD plus 4 μM or 1 μM lysine (Fig. 5A). Plates were observed using light microscopy under a 10× objective after 24 h (4 μM lysine) or 48 h (1 μM lysine). Clusters of five or more cells were considered microcolonies. Percentages and 95% CIs for the ancestor and evolved data in Fig. 5A were estimated by a generalized linear mixed-effect model with a binomial link function using the package lme4 (70). Cooperator/cheater (“type”), ancestor/evolved (“state”), lysine concentration, and lysine concentration/state interaction were fixed effects, whereas strain and strain/experiment interaction were random effects.

Sequencing and Analysis.

Genomic DNA was extracted using the Genomic-tip 20/G kit (QIAGEN). Libraries were prepared using the tagmentation reaction through the Nextera DNA Sample Preparation Kit, the Nextera Index Kit (96 indices), and TruSeq Dual Index Sequencing Primers (Illumina). All clean-up steps were performed with DNA Clean and Concentrator-5 (Zymo Research). Libraries from 30 strains (including the ancestral  and

and  ) were multiplexed and run on a HiSeq2000 (Illumina) using 50-cycle paired-end reading. Sequence data were analyzed using a custom Perl script that incorporated the bwa aligner (71) and SAMtools (72).

) were multiplexed and run on a HiSeq2000 (Illumina) using 50-cycle paired-end reading. Sequence data were analyzed using a custom Perl script that incorporated the bwa aligner (71) and SAMtools (72).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Justin Burton, who initially observed stochastic cheater outcomes; Wayne Gerard for performing the experiment used to generate Fig. 3A; Aric Capel for assistance with strain construction; Sarah Holte for help with statistical analysis; and Andy Marty and Ryan Basom for help with sequencing. Work in the W.S. group is supported by the W. M. Keck Foundation, the National Institutes of Health (Grant 1 DP2 OD006498-01), and the National Science Foundation Bio/computation Evolution in Action CONsortium (BEACON) Science and Technology Center.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1210190109/-/DCSupplemental.

See Commentary on page 19037.

References

- 1.Hollén LI, Radford AN. The development of alarm call behaviour in mammals and birds. Anim Behav. 2009;78:791–800. [Google Scholar]

- 2.West SA, Diggle SP, Buckling A, Gardner A, Griffin AS. The social lives of microbes. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2007;38:53–77. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee HH, Molla MN, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Bacterial charity work leads to population-wide resistance. Nature. 2010;467:82–85. doi: 10.1038/nature09354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardin G. The tragedy of the commons. Science. 1968;162:1243–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner PE, Chao L. Prisoner’s dilemma in an RNA virus. Nature. 1999;398:441–443. doi: 10.1038/18913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization 2008. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update (World Health Organization, Geneva) Available at: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/index.html. Accessed May 22, 2012.

- 7.Naumov GI, Naumova ES, Sancho ED, Korhola MP. Polymeric SUC genes in natural populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;135:31–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb07962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strassmann JE, Zhu Y, Queller DC. Altruism and social cheating in the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature. 2000;408:965–967. doi: 10.1038/35050087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaber JA, et al. Analysis of quorum sensing-deficient clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:841–853. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45617-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobata S, Tsuji K. A cheater lineage in a social insect: Implications for the evolution of cooperation in the wild. Commun Integr Biol. 2009;2:67–70. doi: 10.4161/cib.7466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vos M, Velicer GJ. Social conflict in centimeter-and global-scale populations of the bacterium Myxococcus xanthus. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1763–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilder CN, Allada G, Schuster M. Instantaneous within-patient diversity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing populations from cystic fibrosis lung infections. Infect Immun. 2009;77:5631–5639. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00755-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jandér KC, Herre EA. Host sanctions and pollinator cheating in the fig tree-fig wasp mutualism. Proc Biol Sci. 2010;277:1481–1488. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster KR, Shaulsky G, Strassmann JE, Queller DC, Thompson CRL. Pleiotropy as a mechanism to stabilize cooperation. Nature. 2004;431:693–696. doi: 10.1038/nature02894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greig D, Travisano M. The Prisoner’s Dilemma and polymorphism in yeast SUC genes. Proc Biol Sci. 2004;271(Suppl 3):S25–S26. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gore J, Youk H, van Oudenaarden A. Snowdrift game dynamics and facultative cheating in yeast. Nature. 2009;459:253–256. doi: 10.1038/nature07921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doebeli M, Hauert C. Models of cooperation based on the Prisoner’s Dilemma and the Snowdrift game. Ecol Lett. 2005;8:748–766. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster KR. Diminishing returns in social evolution: The not-so-tragic commons. J Evol Biol. 2004;17:1058–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Archetti M, Scheuring I. Coexistence of cooperation and defection in public goods games. Evolution. 2011;65:1140–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MaClean RC, Fuentes-Hernandez A, Greig D, Hurst LD, Gudelj I. A mixture of “cheats” and “co-operators” can enable maximal group benefit. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kümmerli R, Jiricny N, Clarke LS, West SA, Griffin AS. Phenotypic plasticity of a cooperative behaviour in bacteria. J Evol Biol. 2009;22:589–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kümmerli R, Brown SP. Molecular and regulatory properties of a public good shape the evolution of cooperation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18921–18926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011154107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fletcher JA, Doebeli M. A simple and general explanation for the evolution of altruism. Proc Biol Sci. 2009;276:13–19. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton WD. The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I. J Theor Biol. 1964;7:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trivers RL. The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Q Rev Biol. 1971;46:35–57. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Axelrod R, Hamilton WD. The evolution of cooperation. Science. 1981;211:1390–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.7466396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strassmann JE, Gilbert OM, Queller DC. Kin discrimination and cooperation in microbes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:349–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiers ET, Rousseau RA, West SA, Denison RF. Host sanctions and the legume-rhizobium mutualism. Nature. 2003;425:78–81. doi: 10.1038/nature01931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heath KD, Tiffin P. Stabilizing mechanisms in a legume-rhizobium mutualism. Evolution. 2009;63:652–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maynard Smith J. Group selection and kin selection. Nature. 1964;201:1145–1147. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chao L, Levin BR. Structured habitats and the evolution of anticompetitor toxins in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6324–6328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nowak MA, May RM. Evolutionary games and spatial chaos. Nature. 1992;359:826–829. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harcombe W. Novel cooperation experimentally evolved between species. Evolution. 2010;64:2166–2172. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hauert C, Doebeli M. Spatial structure often inhibits the evolution of cooperation in the snowdrift game. Nature. 2004;428:643–646. doi: 10.1038/nature02360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen SK, Rainey PB, Haagensen JA, Molin S. Evolution of species interactions in a biofilm community. Nature. 2007;445:533–536. doi: 10.1038/nature05514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verbruggen E, et al. Spatial structure and interspecific cooperation: Theory and an empirical test using the mycorrhizal mutualism. Am Nat. 2012;179:E133–E146. doi: 10.1086/665032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Queller DC. Does population viscosity promote kin selection? Trends Ecol Evol. 1992;7:322–324. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(92)90120-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.West SA, Pen I, Griffin AS. Cooperation and competition between relatives. Science. 2002;296:72–75. doi: 10.1126/science.1065507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Griffin AS, West SA, Buckling A. Cooperation and competition in pathogenic bacteria. Nature. 2004;430:1024–1027. doi: 10.1038/nature02744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shou W, Ram S, Vilar JMG. Synthetic cooperation in engineered yeast populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1877–1882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610575104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu H, Styles CA, Fink GR. Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C has a mutation in FLO8, a gene required for filamentous growth. Genetics. 1996;144:967–978. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.3.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Momeni B, Chen C-C, Hillesland KL, Waite A, Shou W. Using artificial systems to explore the ecology and evolution of symbioses. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:1353–1368. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0649-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Armitt S, Woods RA. Purine-excreting mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. I. Isolation and genetic analysis. Genet Res. 1970;15:7–17. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300001324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blickling S, Knäblein J. Feedback inhibition of dihydrodipicolinate synthase enzymes by L-lysine. Biol Chem. 1997;378:207–210. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1997.378.3-4.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin CH, MacGurn JA, Chu T, Stefan CJ, Emr SD. Arrestin-related ubiquitin-ligase adaptors regulate endocytosis and protein turnover at the cell surface. Cell. 2008;135:714–725. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swaminathan S, Amerik AY, Hochstrasser M. The Doa4 deubiquitinating enzyme is required for ubiquitin homeostasis in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2583–2594. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.8.2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dupré S, Haguenauer-Tsapis R. Deubiquitination step in the endocytic pathway of yeast plasma membrane proteins: Crucial role of Doa4p ubiquitin isopeptidase. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4482–4494. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4482-4494.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Springael JY, Galan JM, Haguenauer-Tsapis R, André B. NH4+-induced down-regulation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Gap1p permease involves its ubiquitination with lysine-63-linked chains. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:1375–1383. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.9.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grenson M, Hou C, Crabeel M. Multiplicity of the amino acid permeases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. IV. Evidence for a general amino acid permease. J Bacteriol. 1970;103:770–777. doi: 10.1128/jb.103.3.770-777.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Regenberg B, Düring-Olsen L, Kielland-Brandt MC, Holmberg S. Substrate specificity and gene expression of the amino-acid permeases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1999;36:317–328. doi: 10.1007/s002940050506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luhtala N, Odorizzi G. Bro1 coordinates deubiquitination in the multivesicular body pathway by recruiting Doa4 to endosomes. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:717–729. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grenson M. Multiplicity of the amino acid permeases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. II. Evidence for a specific lysine-transporting system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;127:339–346. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(66)90388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lenski RE, Travisano M. Dynamics of adaptation and diversification: A 10,000-generation experiment with bacterial populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6808–6814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morgan AD, Quigley BJZ, Brown SP, Buckling A. Selection on non-social traits limits the invasion of social cheats. Ecol Lett. 2012;15:841–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Santos M, Szathmáry E. Genetic hitchhiking can promote the initial spread of strong altruism. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:281. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith JM, Haigh J. The hitch-hiking effect of a favourable gene. Genet Res. 1974;23:23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwilk DW, Kerr B. Genetic niche-hiking: An alternative explanation for the evolution of flammability. Oikos. 2002;99:431–442. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chuang JS, Rivoire O, Leibler S. Simpson’s paradox in a synthetic microbial system. Science. 2009;323:272–275. doi: 10.1126/science.1166739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Velicer GJ, Vos M. Sociobiology of the myxobacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:599–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fiegna F, Velicer GJ. Competitive fates of bacterial social parasites: Persistence and self-induced extinction of Myxococcus xanthus cheaters. Proc Biol Sci. 2003;270:1527–1534. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morgan AD, Quigley BJ, Brown SP, Buckling A. Selection on non-social traits limits the invasion of social cheats. Ecol Lett. 2012;15:841–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lang GI, Botstein D, Desai MM. Genetic variation and the fate of beneficial mutations in asexual populations. Genetics. 2011;188:647–661. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.128942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brachmann CB, et al. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: A useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast. 1998;14:115–132. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980130)14:2<115::AID-YEA204>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guthrie C, Fink GR, editors. Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 65.R Core Team 2011. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna). Available at http://www.R-project.org. Accessed September 26, 2012.