Abstract

Bacillus species form an heterogeneous group of Gram-positive bacteria that include members that are disease-causing, biotechnologically-relevant, and can serve as biological research tools. A common feature of Bacillus species is their ability to survive in harsh environmental conditions by formation of resistant endospores. Genes encoding the universal stress protein (USP) domain confer cellular and organismal survival during unfavorable conditions such as nutrient depletion. As of February 2012, the genome sequences and a variety of functional annotations for at least 123 Bacillus isolates including 45 Bacillus cereus isolates were available in public domain bioinformatics resources. Additionally, the genome sequencing status of 10 of the B. cereus isolates were annotated as finished with each genome encoded 3 USP genes. The conservation of gene neighborhood of the 140 aa universal stress protein in the B. cereus genomes led to the identification of a predicted plasmid-encoded transcriptional unit that includes a USP gene and a sulfate uptake gene in the soil-inhabiting Bacillus megaterium. Gene neighborhood analysis combined with visual analytics of chemical ligand binding sites data provided knowledge-building biological insights on possible cellular functions of B. megaterium universal stress proteins. These functions include sulfate and potassium uptake, acid extrusion, cellular energy-level sensing, survival in high oxygen conditions and acetate utilization. Of particular interest was a two-gene transcriptional unit that consisted of genes for a universal stress protein and a sirtuin Sir2 (deacetylase enzyme for NAD+-dependent acetate utilization). The predicted transcriptional units for stress responsive inorganic sulfate uptake and acetate utilization could explain biological mechanisms for survival of soil-inhabiting Bacillus species in sulfate and acetate limiting conditions. Considering the key role of sirtuins in mammalian physiology additional research on the USP-Sir2 transcriptional unit of B. megaterium could help explain mammalian acetate metabolism in glucose-limiting conditions such as caloric restriction. Finally, the deep-rooted position of B. megaterium in the phylogeny of Bacillus species makes the investigation of the functional coupling acetate utilization and stress response compelling.

Keywords: ATP-binding, acetate utilization, Bacillus, Bacillus cereus, Bacillus megaterium, Sir2, sirtuins, sulfate uptake, universal stress proteins

Introduction

Bacillus species form an heterogeneous group of Gram-positive bacteria that include members that are disease-causing, biotechnologically-relevant, and can serve as biological research tools.1–5 A common feature of Bacillus species is their ability to survive in harsh environmental conditions via the formation of resistant endospores. Regulation of gene activity in response to environmental conditions is a well-defined mechanism in Bacillus.2 The formation and germination of highly resistant endospores are known responses to unfavorable environmental conditions.6 These dormant cells allow Bacillus species to survive extreme conditions such as elevated temperatures, extreme pH and salinity changes. The physiological feature of spore formation is evident in food processing, where exposure to mild preservation elicits an adaptive stress response, resulting in Bacillus spores found in food.7 Because spores can also attach to numerous substrates8 and persist in the soil for years9, detection of genes associated with their survival could be critical in understanding pathogenesis of endospore-forming Bacillus species.

Genes encoding the universal stress protein (USP) domain have been detected in diverse organisms, including plants, bacteria and fungi.10,11 The universal stress proteins (defined by the Protein Family (Pfam) accession PF00582) confer survival during extreme conditions such as drought,12 osmolarity,13 oxidative stress due to hydrogen peroxide14 and acid response.15 The universal stress proteins have been classified broadly based on their ability to bind or not bind ATP.16,17 The soil-inhabiting Bacillus subtilis must overcome unfavorable conditions in the soil, including nutritional stresses.18 Before the completion of the genome sequence of B. subtilis 168, genomic regions containing genes that encode the USP domain were investigated. The yxiE gene, which encodes a 148 aa protein, was shown to be part of a three-gene operon for aryl-beta-glucoside utilization and the operon induced only when cells were grown in salicin, a plant-derived carbohydrate.19 Additionally, yxiE was revealed by DNA sequencing to be in the genomic region between the histidine utilization operon (hut) and wall-associated protein A (wapA) loci in the B. subtilis 168 genome.20 Another USP domain encoding gene, nhaX (also termed yheK) was found between a serine protein kinase (prkA) and ATP-dependent nuclease (addAB) loci in the B. subtilis 168 genome.21 Both yxiE and yheK are induced in phosphate starvation.22 The public availability of the genome sequences of more than 100 Bacillus isolates present new opportunities to extensively analyze the functional annotation of the universal stress proteins encoded in Bacillus genomes.

As of February 2012, the genome sequences and a variety of functional annotations for at least 123 Bacillus isolates, including 45 Bacillus cereus isolates, were available in the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) database and comparative analysis system.23 The number of USP gene per Bacillus genome ranged from 1 (strains ATCC 7061 and SAFR-032 of Bacillus pumilus) to 6 (Bacillus megaterium QM B1551 and B. selenitireducens MLS10). The draft genome of marine Bacillus species NRRL B-1491124 encodes 5 USP genes. Additionally, the genome sequencing status of 10 of the B. cereus isolates were annotated as finished with each genome encoded with 3 USP genes. Clustering the USPs from the 10 genomes by amino acid length revealed two USPs (140 aa and 152 aa) that encoded only the universal stress protein domain. The third gene encoded protein where a kinase domain is present with the USP domain.

The reported research focused on the two B. cereus genes that encode only the USP domain. The annotated function and direction of transcription of adjacent genes of the two Bacillus cereus USP genes were determined in the 10 finished genomes. Further, the identity of the amino acid for binding to ATP and other ligands in orthologous universal stress proteins of Bacillus cereus were compared and the transcription of two USP genes in growing cultures of a strain of B. cereus were determined. The conservation of the gene neighborhood of the 140 aa USP in the B. cereus genomes led to the identification of a predicted plasmid-encoded transcriptional unit that includes a USP gene and a sulfate uptake gene in the soil-inhabiting B. megaterium. Additional gene neighborhood analysis of genes for universal stress proteins in B. megaterium identified a predicted two-gene transcriptional unit that consists of a USP gene and a sirtuin (deacetylase enzyme for NAD+-dependent acetate utilization). The predicted transcriptional units for stress responsive inorganic sulfate uptake and acetate utilization could explain biological mechanisms for survival of soil-inhabiting Bacillus species in sulfate and acetate limiting conditions.

Materials and Methods

Function and transcription direction of adjacent genes for genes encoding universal stress proteins

The function and transcription direction of adjacent genes for two genes encoding universal stress proteins were compared for the following 10 finished Bacillus cereus genomes: 03BB102; AH187 (F4810/72); AH820; B4264; ATCC 10987; ATCC 14579; cytotoxis NVH 391–98; G9842; Q1 and E33L (ZK). The Gene Neighborhoods function in the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) system (http://img.jgi.doe.gov/)23 was used to construct a chromosomal map of the regions with the two genes encoding the 140 aa and 152 aa universal stress proteins. The transcription direction and function (as defined by Cluster of Orthologous Groups [COG] of Proteins; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/) were determine for the adjacent genes. To facilitate the comparison of the adjacent genes, we used a 3-digit binary accession to encode the direction of the transcription, 1 in the same transcription direction as the USP gene and 0 in the opposite transcription direction of the USP gene. The transcription direction for the USP gene was assigned a 1. The binary accession allows us to predict stress response equipped biological functions. Therefore, a binary accession of 111, 110, 011 are potential chromosomal encoded pathways. The potential pathways are further verified using transcriptional units provided by the BioCyc Collection of Pathway and Genome Databases.25 In BioCyc (http://biocyc.org/), a transcription unit is defined as a set of one or more genes that are transcribed to produce a single messenger RNA. We were interested in a transcriptional unit with more than one gene and included a gene encoding at least a universal stress protein.

Prediction of ligand binding sites for Bacillus cereus universal stress proteins

The amino acid residues for ATP binding and other ligands for the 30 Bacillus cereus universal stress proteins were predicted using the web interface to the Batch Conserved Domain (CD)-Search available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi.26 The GenBank protein accession for the protein sequences were obtained from the Integrated Microbial Gemone (IMG) system and submitted to Batch CD-Search. The ligand binding sites predicted for the USPs were processed using a computer script into a data set suitable for comparison of the ligand binding sites. Each record of the dataset consisted of (i) amino acid residue; (ii) position of the amino acid in the sequence; (iii) GenBank Accession; (iv) Ligand Site position; (v) ligand type; (vi) Protein domain type; and (vii) protein domain in Conserved Domain Database. The data set was processed using a Visual Analytics software (http://www.tableausoftware.com/public/) to compare the identity of the amino acid residues involved in ligand binding. A visual analytics approach can enable knowledge building biological insights to be accomplished from analyzing mutiple types of datasets.27–30

Bacterial strains and cultures

Strain ATCC 10876 (also referred to as strain 569) was selected as the Bacillus cereus strain for detection of genes for universal stress proteins. Strain ATCC 10876 has been investigated for diverse biological processes, including response to iron limitation31 and production of metal-dependent beta lactamases.32B. cereus ATCC 10876, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas VA, USA) was cultured overnight in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth overnight at 37 °C and 200 rpm. The resulting bacterial cultures were diluted to OD600 0.01 in BHI and incubated for four hours at 37 °C and 200 rpm.

Total RNA isolation

Total RNA was isolated according to the instructions in the Fisher BioReagents SurePrep TrueTotal RNA Purification Kit. Bacillus cells were pelleted by centrifuging at 14,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was decanted and the cell pellet was mixed thoroughly with lysozyme (3 mg/mL). After a 10 minute incubation at room temperature, Fisher lysis solution was added to the mixture and the sample vortexed vigorously. The sample was centrifuged to remove any intact cells before the samples were applied to the Fisher SurePrep column. The samples were washed with ethanol several times and the cDNA isolated by elution buffer. The RNA concentration was determined by the Nanodrop Spectrophotometers.

End point reverse transcription (RT) polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The expression of USP genes was examined by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). RT-PCR was performed according to the manufactor’s directions (Invitrogen, Super Script One Step RT-PCR System). The Invitrogen Oligo Perfect system was used to design primers to genes encoding two B. cereus USPs ZP04319786 and ZP04315896 as well as tuf gene, encoding elongation factor Tu. RT-PCR was performed as follows: 1 cycle for 15 minutes at 45 °C and 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 seconds, annealing at 57 °C for 30 seconds, and extention for 1 minute at 68 °C.

DNA gel electrophoresis

Gel Electrophoresis was used to visualize RT-PCR products. Agarose (0.32 grams) was dissolved in 1X Tris Borate EDTA (TBE) and heated. After the mixture was allowed to cool, ethidium bromide was added to the solution (4 microliters), mixed, and the warm solution was poured in to the horizontal casting trays. Samples were diluted with running buffer (10 microliters of sample and 2 microliters of loading dye) and separated for 45 minutes at 100 volts. Bands were visualized and photographed using the Versa-Doc (BioRad).

Results

Function and transcription direction of adjacent genes for genes encoding universal stress proteins

The strain designation, GenBank Project ID, Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) Taxon ID and gene count for 10 finished (completely sequenced) Bacillus cereus genomes are presented in Table 1. Of the strains analyzed, strain ATCC 10987 had the highest gene count of 6,126 genes while strain cytotoxis NVH 391–98 had the lowest gene count of 4,250 genes. The accession numbers of the 2 universal stress proteins in each selected B. cereus genome are presented in Table 2. The predicted function of the adjacent genes and the encoding for the transcription direction is presented in Tables 3 and 4 respectively.

Table 1.

Bacillus cereus strains with finished genome sequences.

| Bacillus cereus genome | GenBank Project ID | IMG Taxon ID* | Gene count |

|---|---|---|---|

| 03BB102 | 31307 | 643692007 | 5,767 |

| AH187 (F4810/72) | 17715 | 643348510 | 5,903 |

| AH820 | 17711 | 643348511 | 5,941 |

| ATCC 10987 | 74 | 637000016 | 6,126 |

| ATCC 14579 | 384 | 637000017 | 5,513 |

| B4264 | 17731 | 643348512 | 5,557 |

| cytotoxis NVH 391–98 | 13624 | 640753006 | 4,250 |

| E33L (ZK) | 12468 | 637000018 | 5,886 |

| G9842 | 17733 | 643348513 | 5,994 |

| Q1 | 16220 | 643348514 | 5,621 |

Note:

IMG: Integrated Microbial Genomes system.

Table 2.

Accesion numbers and locus tags of universal stress proteins in selected Bacillus cereus genomes.

| Bacillus cereus genome | GenBank Accesssion (140 aa USP) | Locus tag (140 aa USP) | GenBank Accesssion (152 aa USP) | Locus tag (152 aa USP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 03BB102 | YP_002748010 | BCA_0692 | YP_002751985 | BCA_4741 |

| AH187 (F4810/72) | YP_002336786 | BCAH187_A0783 | YP_002340677 | BCAH187_A4754 |

| AH820 | YP_002449684 | BCAH820_0711 | YP_002453689 | BCAH820_4743 |

| ATCC 10987 | NP_977047 | BCE_0722 | NP_981053 | BCE_4760 |

| ATCC 14579 | NP_830469 | BC0655 | NP_834331 | BC4625 |

| B4264 | YP_002365450 | BCB4264_A0690 | YP_002369419 | BCB4264_A4733 |

| Cytotoxis NVH 391–98 | YP_001373894 | Bcer98_0550 | YP_001376514 | Bcer98_3301 |

| E33L (ZK) | YP_082171 | BCZK0565 | YP_085948 | BCZK4370 |

| G9842 | YP_002444119 | BCG9842_B4648 | YP_002448190 | BCG9842_B0502 |

| Q1 | YP_00252867 | BCQ_0722 | YP_002532148 | BCQ_4433 |

Table 3.

Function of adjacent genes of universal stress protein (140 aa) in selected Bacillus cereus genomes.

| Strain | Function before* | Function after* | Binary accession |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxis NVH 391–98 | COG0659 | COG0747 | 110 |

| E33L (ZK) | COG0659 | COG0747 | 110 |

| 03BB102 | COG0659 | COG0000 | 111 |

| AH187 (F4810/72) | COG0659 | COG0000 | 111 |

| AH820 | COG0659 | COG0000 | 111 |

| B4264 | COG0659 | COG0000 | 111 |

| ATCC 10987 | COG0659 | COG0000 | 111 |

| ATCC 14579 | COG0659 | COG2271 | 110 |

| G9842 | COG0659 | COG0000 | 111 |

| Q1 | COG0659 | COG0000 | 111 |

Note:

The before and after gene is based on numerical order of the locus tag. COG: Cluster of Orthologous Groups of Proteins. COG0659: Sulfate permease and related transporters (MFS superfamily); COG0747: ABC-type dipeptide transport system, periplasmic component; COG227: Sugar phosphate permease.

Table 4.

Function of adjacent genes of universal stress protein (152 aa) in selected Bacillus cereus genomes.

| Strain | Before* | After* | Binary accession |

|---|---|---|---|

| AH187 (F4810/72) | COG1028 | COG0000 | 010 |

| AH820 | COG1028 | COG0000 | 010 |

| B4264 | COG1028 | COG0000 | 010 |

| ATCC 10987 | COG1028 | COG0000 | 010 |

| ATCC 14579 | COG1028 | COG0000 | 010 |

| Cytotoxis | COG1028 | COG0000 | 010 |

| NVH 391–98 | |||

| G9842 | COG1028 | COG0000 | 010 |

| E33L (ZK) | COG1028 | COG0000 | 010 |

| 03BB102 | COG1028 | COG0000 | 010 |

| Q1 | COG1028 | COG0000 | 011 |

Notes:

The before and after gene is based on numerical order of the locus tag. COG: Cluster of Orthologous Groups of Proteins. COG1028: Dehydrogenases with different specificities (related to short-chain alcohol dehydrogenases; COG0000: No COG annotation.

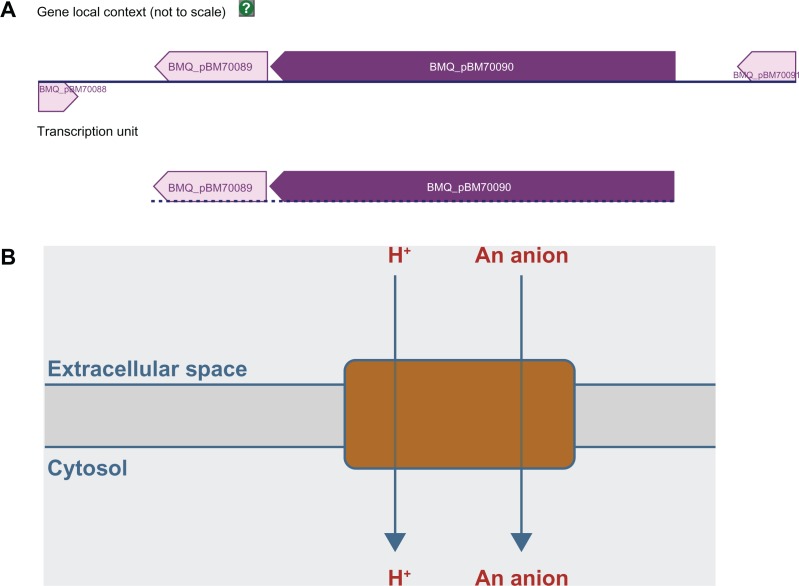

In the case of the gene for the 140 aa USP, the function of the gene before the USP gene in the 10 genes was COG0659 [Sulfate permease and related transporters (MFS superfamily)] (Table 2). For two strains (cytotoxis NVH 391–98 and E33L [ZK]) the function of the gene was predicted as COG0747 (ABC-type dipeptide transport system, periplasmic component). The gene after the USP in strain ATCC 14579 was annotated as COG2271 (Sugar phosphate permease). For transcription direction, only strains cytotoxis NVH 39–98, E33L (ZK) and ATCC 14579 had the adjacent gene after the USP gene in the opposite direction of the USP gene. The other genomes had the adjacent genes to the USP gene in same direction hence the encoding of 111. A code COG0000 was introduced to indicate that the no COG function was assigned for the adjacent gene, as well as to facilitate computer processing of the results. In summary, the B. cereus gene for the 140 aa USP is adjacent to the gene for inorganic sulfate uptake in the 10 genomes investigated. Additional inspection of the neighborhood of 92 USP genes from 36 finished genomes of other Bacillus species identified in the non-pathogenic, soil-inhabiting Bacillus megaterium QM B1551 a plasmid-encoded universal stress protein with locus tag BMQ_pBM70089.5 The gene BMQ_pBM70089 and the adjacent sulfate transporter (BMQ_pBM70090) form a transcriptional unit according to predictions in the BioCyc database (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Gene neighborhood and schematic diagram of inorganic sulfate transport in Bacillus megaterium. Chromosomal location and (A) Gene local context and transcription unit in Bacillus megaterium plasmid pBM700 with gene for universal stress protein (BMQ_pBM70089) and gene for inorganic sulfate transport (BMQ_pBM70090). A dashed baseline indicates that there is no high-quality evidence to confirm the extent of this transcription unit. (B) Enzymatic reaction of inorganic anion transporter, sulfate permease (SulP) family.

Source of images: http://biocyc.org/.

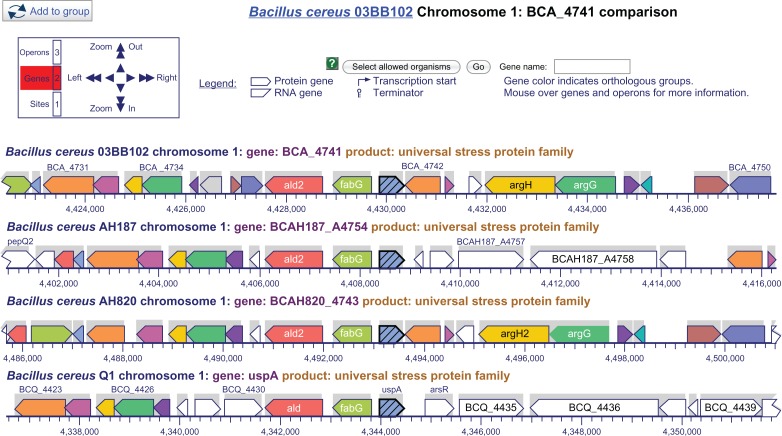

In the B. cereus genes encoding 152 aa USP, all the genes after the USP gene have not been mapped to a known COG function. In all the strains the gene before the USP was in the opposite transcription direction and annotated with function “Dehydrogenases with different specificities (related to short-chain alcohol dehydrogenases)” [COG1028]. Only strain Q1 had an adjacent gene in the same direction of transcription. The gene encodes a transcriptional regulator of the ArsR family that enable bacteria and archaea to respond to stress induced by heavy metal toxicity33 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Multi-genome alignment of gene neigbhorhood of genes for universal stress protein representative Bacillus cereus genomes.

Notes: Universal stress protein (USP) gene in blue with diagonal lines. Bacillus cereus Q1 is only genome with transcriptional regulator of the ArsR family. Source of image: http://biocyc.org/.

Genes encoding universal stress proteins of Bacillus megaterium in transcriptional units

The presence of a USP encoding gene in the plasmid genome of strain QM B1551, the unique large morphological size (4 × 1.5 μm),34 and the availability of finished genomes from three strains35,36 led to our interest in further research on the USP genes of B. megaterium. The 3.5 release (January 2012) of the Integrated Microbial Genomes resource includes genomic information and functional annotations for the chromosomal genomes of strains QM B1551 and DSM 319 as well as seven plasmid genomes of strain QM B1551. Strain DSM 319 is plasmid-less and the chromosome has 3 USPs with locus tags (BMD_1865, BMD_1891 and BMD_3975). Strain QM B1551 has a total of 5 USP genes (BMQ_1747, BMQ_1871, BMQ1905, BMQ_3025, BMQ_3990) encoded on the chromosome while a sixth USP gene (BMQ_pBM70089) is located on a plasmid. In addition to the plasmid-encoded transcriptional unit in QM B1551, the genome of the two B. megaterium strains encode a two-gene transcriptional unit encoding a silent information regulator 2 (Sir2) family transcriptional regulator and a universal stress protein. The USPs are BMQ_3990 and BMD_3975 from QM B1551 and DSM 319 respectively.

Gene neighborhood and chromosomal cassette analyses performed on the IMG resource revealed that the USP-Sir2 transcriptional unit is unique to B. megaterium. The chromosomal cassette showing the unique presence of the Sir2 and USP as adjacent genes in strains of B. megaterium can be view at http://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/w/main.cgi?section=GeneCassette&page=geneCassette&gene_oid=646729802&type=pfam.

Prediction of ligand binding sites for Bacillus cereus universal stress proteins

The ligand binding site position, the amino acid position and the amino acid for the ligand binding sites for the 140 aa and 152 aa universal stress proteins of B. cereus genomes are presented in Tables 5 and 6 respectively. In the 140 aa USP, nine of the strains had 12 conserved ligand binding sites while strain cytotoxis NVH 391–98 had only 8 of the 12 ligand binding sites. The first ligand binding positions in NVH 391–98 and the other nine 140 aa USPs are 108 and 8 respectively. Further, there was no agreement of the amino acid types in the two USP groups despite having identical sizes (Table 5).

Table 5.

Ligand binding sites for 140 aa universal stress proteins of selected Bacillus cereus strains.

| Ligand binding position | Amino acid position | Amino acid |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | A |

| 2 | 9 | C |

| 3 | 13 | D |

| 5 | 108 | A |

| 6 | 109 | G |

| 7 | 111 | R |

| 8 | 112 | G |

| 9 | 122 | G |

| 10 | 123 | S |

| 11 | 124 | V |

| 12 | 125 | S |

Notes: Conserved in all finished B. cereus strains except for B. cereus cytotoxis NVH 391–98. The 8 binding sites and associated amino acids for strain NVH 391–98 were 108 (V); 109 (C); 111 (R); 112 (G); 123 (S); 124 (V) and 125 (S). The protein domain architecture for Bcer98_0550 of strain NVH 391–98 can be retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi?INPUT_TYPE=live&SEQUENCE=YP_001373894.1. The protein domain architecture for BCA_0692 of strain 03BB102 can be retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi?INPUT_TYPE=live&SEQUENCE=YP_002748010.

Table 6.

Ligand binding sites for 152 aa universal stress proteins of selected Bacillus cereus strains.

| Ligand binding position | Amino acid position | Amino acid |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | A |

| 2 | 12 | V |

| 3 | 13 | D |

| 4 | 41 | I |

| 5 | 112 | C |

| 6 | 113 | G |

| 7 | 115 | T |

| 8 | 116 | G |

| 9 | 126 | G |

| 10 | 127 | S |

| 11 | 128 | V |

| 12 | 129 | S |

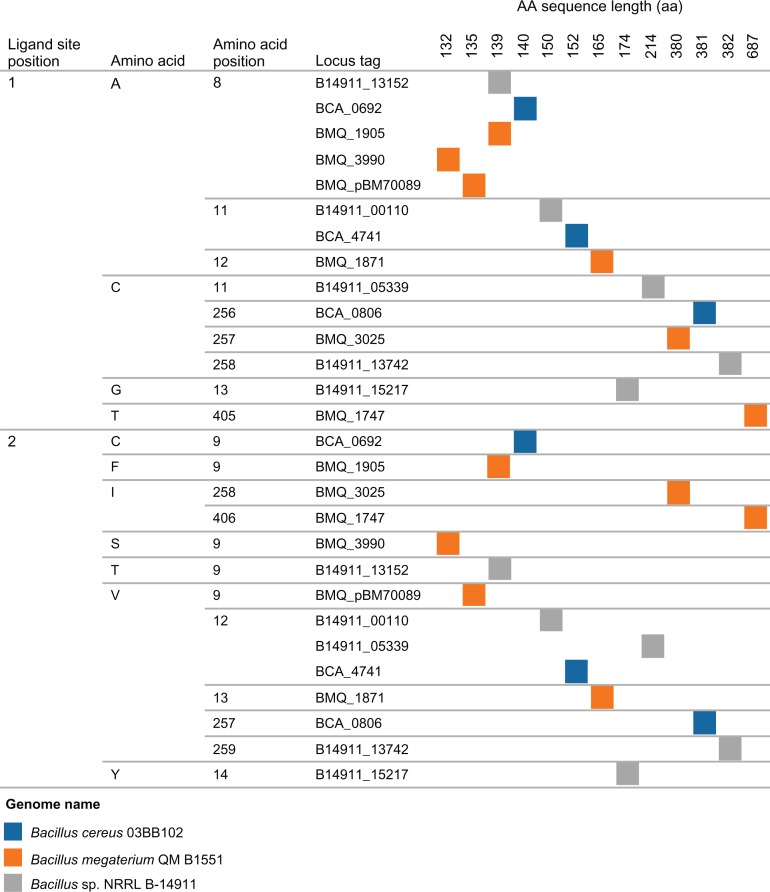

Comparative analysis of chemical ligand binding sites and gene neighborhood of universal stress proteins in Bacillus genomes

The amino acids sites for chemical ligand binding for the sequences of the universal stress proteins from B. cereus 03BB102 (3 USP genes) were compared to B. megaterium QM B1551 and Bacillus sp. NRRL B-14911. The latter two genomes were selected because of they have 6 and 5 USP genes respectively and form a clade when their 16S rRNA genes were analyzed.24 A total of 12 ligands binding sites is expected for a complete USP domain (PF00582) following that of Methanococcus jannaschii MJ0577 protein.16 Clustering the features of ligand binding sites (position, amino acid and amino acid position) for 14 USP sequences revealed shared ligand binding sites (possible orthologous USPs) as well as unique ligand binding sites (possible unique regulation or strain-specific regulation) (Fig. 3). In the first ligand site position 8 of the 14 sequences were Alanine (A). The clustering using ligand site position 1 also separated the 6 B. megaterium USPs into 3 classes based on the amino acid. BMQ_1905, BMQ_3990 and BMQ_pBM70089 were annotated to have binding site at position 8. The 687 aa BMQ_1747 was annotated as a Na+/H+ antiporter for ejecting protons from cells with the goal of effectively eliminating excess acid from actively metabolizing cells.26 The 380 aa BMQ_3025 was annotated as a potassium uptake protein (osmosensitive K+ channel histidine kinase sensor). BMQ_3025 is in the same transcriptional unit with BMQ_3024 which encodes a protein with cystathionine-beta-synthase (CBS) domain known for binding to adenosine for cellular energy-sensing.37 Multi-genome alignment of several Bacillus genomes revealed the gene for CBS domain in several Bacillus genomes. However, transcriptional unit encoding possible stress responsive potassium uptake and energy sensing was found in B. megaterium QM B1551. The 165 aa BMQ1871 is not part of a transcriptional unit but is adjacent to a high oxygen, responsive, 4-member transcriptional unit encoding subunits of cytochrome o quinol oxidase (cyoABCD), homolog of one of the terminal oxidases identified in Escherichia coli.38

Figure 3.

Visualization of clustering of ligand binding sites from universal stress protein sequences of selected Bacillus species.

Notes: An interpretation of the visualization is that of the 14 sequences, 8 sequences have Alanine (A) in ligand position 1 of the universal stress protein ligand binding signature. It could be inferred that proteins B14911_13742 and BMQ_1747 have unique ligand binding sites of Glycine (G) and Threonine respectively.

Detection of genes encoding universal stress proteins in B. cereus ATCC 10876

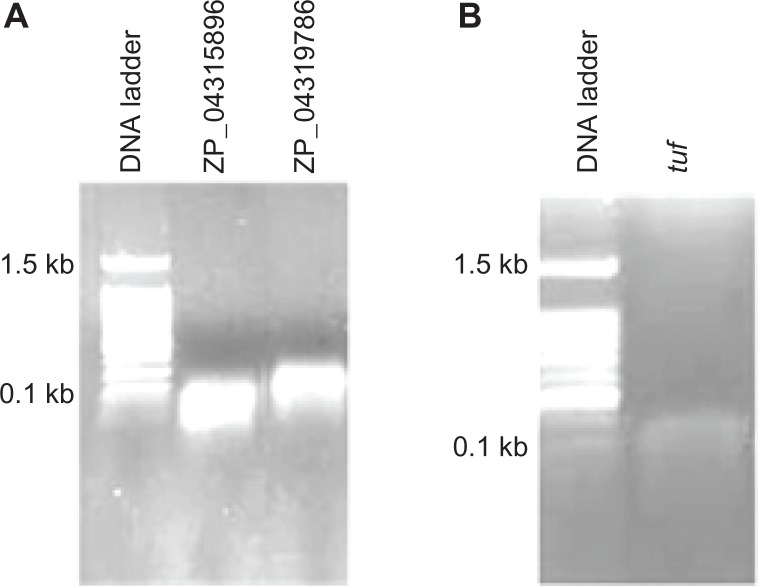

Vegetative B. cereus cells were isolated during exponential growth in BHI at 37 °C. Total RNA was extracted from cells for end point reverse transcription PCR. Both putative genes for two USPs (ZP04319786 and ZP04315896) and a control gene, tuf, were detected to be transcribed during the latter stages of exponential growth in BHI (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Confirmation of expression of genes for universal stress proteins in Bacillus cereus ATCC 10876. (A) Bands in the DNA gel demonstrate that both genes are expressed during the latter stages of exponential growth in Brain Heart Infusion broth. (B) Expression of tuf (elongation factor Tu) was used as a control to measure RNA isolation.

Discussion

The public availability of at least 100 genome sequences of Bacillus species presents new opportunities to use bioinformatic approaches to predict biological processes. These predictions could lead to diverse societally beneficial applications, including disease treatment and prevention, improved agricultural productivity and industrial biotechnological applications. At least 45 genomes of Bacillus cereus are in the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG),23 making it the species with the highest number of genomes sequenced within the Bacillus genera. Each of these genomes have 3 USP genes. One of the USP genes encode protein domains for the enzyme kinase function. The B. cereus USP genes of interest in the reported research were those that encodes only the USP domain (Pfam Identifier: PF00582). Functional annotation analytics were peformed on 10 finished B. cereus genomes: 03BB102; AH187 (F4810/72); AH820; B4264; ATCC 10987; ATCC 14579; cytotoxis NVH 391–98; G9842; Q1 and E33L (ZK). All the 10 B. cereus genomes have genes encoding the 140 aa and 152 aa USPs. Comparing the predicted function and direction of transcription of adjacent genes of USP genes could identify similarities and differences between the chromosomal regions containing the USP genes in multiple genomes from the same species. Furthermore, the comparsions could provide information on biological pathways in which universal stress proteins function. The findings could better define differential physiological responses to environmental stresses of B. cereus strains.

The soil-inhabiting B. megaterium QM B1551 has 6 USP genes, including one on a plasmid. Unlike B. subtilis (another soil-inhabiting Bacillus species), where the two USP genes have been characterized,19,21,22 the functions of the B. megaterium USPs have not been investigated. Gene neighborhood analysis (Figs. 1 and 2) combined with visual analytics of chemical ligand binding sites data (Fig. 3) provided knowledge-building insights on possible cellular functions of B. megaterium universal stress proteins. These functions include sulfate and potassium uptake, acid extrusion, cellular energy-level sensing, survival in high oxygen conditions and acetate utilization. Of particular interest was a transcriptional unit found in only Bacillus megaterium that consisted of a USP gene and a sirtuin (Sir2) gene. The Sir2 is a highly conserved deacetylase enzyme from bacteria to higher eukaryotes that depends on a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide ion (NAD+) to remove acetyl groups from lysine amino acids in proteins.39,40 In general, Sir2 proteins have roles in cell aging, chromosomal stability, energy metabolism in response to nutrient signals, gene silencing and stress response.41,42 In mammals, members of the sirtuin gene family have been extensively investigated, including as therapeutic targets for age-related disorders,43 cancer,44 cardiovascular diseases45 and obesity.40 In B. subtilis, the NAD+ dependent sirtuin (SrtN) and another non-NAD+-dependent deacetylases AcuC are required to maintain the acetyl coenzyme A (Ac-CoA) synthetase (AcsA) enzyme as active (i.e. deacetylated) so that the cell can grow with low concentrations of acetate.46 The conversion of acetate into Ac-CoA is an inducible pathway catalyzed by AcsA and expressed in low extracellular concentrations of acetate.41 In Escherichia coli K12, in the absence of other substrates acetate can serve as sole source of carbon and energy.

The function of the unique USP-Sir2 transcriptional unit in the physiology of B. megaterium has not been reported. The transcriptional unit is present in the all three strains (DSM 319, QM B1551 and WSH-002) with a published genome sequence. One possiblity is the efficient utilization of acetate as a soil-inhabiting bacteria or in conditions of low acetate. Considering the key role of sirtuins in mamalian physiology, additional research on the USP-Sir2 transcriptional unit of B. megaterium could help explain mammalian acetate metabolism in glucose-limiting conditions such as caloric restriction.47 Additional gene transcriptional and protein structure investigations are needed to determine the genomic regulation and protein–protein interaction of the USP-Sir2 transcriptional unit. Finally, the deep-rooted position of B. megaterium in the phylogeny of the Bacillus species36 makes the investigation of the functional coupling acetate utilization and stress response compelling.

The comparison of the chromosomal region of the gene for the 140 aa USP revealed unique gene function annotation and transcriptional direction for two strains: cytotoxis NVH 391–98 and E33L (ZK). Strain NVH 391–98 was isolated during a severe food (vegetable puree) borne disease outbreak in France in 1998. Recently, strain NVH 391–98 has been proposed as a new Bacillus species called cytotoxicus.1 Strain E33L (ZK) was isolated from a zebra carcass in Namibia and the nearest relative to B. anthracis.48 The prediction of amino acids in ligand binding sites helped to distinguish the 140 aa USP of NVH 391–98 from the other B. cereus strains. In the case of the 152 aa USP, the ligand binding sites were conserved. We previously used ligand binding to cluster 8 universal stress protein sequences of the parasitic platyhelminth Schistosoma mansoni and a caustative agent of Schistosomiasis, a neglected tropical disease.14 The availability of functional annotations of proteins predicted from genome sequences allows for integration of ligand binding information and gene neighborhood. The integration could provide insights on the evolutionary relationships, structure, and biological pathways for members of a gene family.

The 140 aa USP is adjacent to gene for plasma membrane enzyme for environmental inorganic sulfate uptake, the first step in the sulfate assimilation pathway in bacteria and plants.49 Sulfur is required for the synthesis of cysteine and methionine, the two sulfur containing amino acids.50 The close proximity of a gene for stress response and a gene for inorganic sulfate uptake could indicate a coupling of both functions during response to sulfur starvation. Bioinformatic evidence for this functional coupling was observed in the plasmid B700 genomes of B. megaterium QM B1551. where the transcriptional unit included a gene encoding 135 aa USP and a gene for sulfate transport in a plasmid of B. megaterium QM B1551 (Fig. 1).

The transcription of two Bacillus cereus USP genes were observed during exponential growth of vegetative cells in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth at 37 °C. The experimental evidence for transcription during this exponential phase is the first step in our future research on determining the exact function and their response to unfavorable conditions (such as iron limitation), as well as their detection in environmental samples such as ready-to-eat food or food produce.

Conclusion

Bacillus species form an heterogeneous group of Gram-positive bacteria that include members that are disease-causing, biotechnologically-relevant, and can serve as biological research tools. A common feature is their ability to survive in harsh environmental conditions by formation of resistant endospores. Universal stress proteins have been demonstrated to be important during survival in unfavorable conditions in numerous pathogenic microbes. The bioinformatics strategy of mining functional annotations from multiple databases and multiple Bacillus genomes led to the identification of sulfate uptake and acetate utilization pathways that are predicted to be coupled with universal stress proteins in Bacillus megaterium.

Acknowledgements and Funding

The Mississippi INBRE was funded by the National Center for Research Resources (5P20RR016476-11) and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8P20GM103476-11) from the National Institutes of Health; National Science Foundation (EPS-0903787; EPS-1006883; DBI-0958179; DBI-1062057); Louis Stokes Mississippi Alliance for Minority Participation (NSF Grant #HRD-0115807); Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center’s National Resource for Biomedical Supercomputing (T36 GM09355-02); US Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate (2009-ST-062-000014; 2011-ST-062-000048); Research Initiative for Science Enhancement (5R25GM067122-06) and Research Centers in Minority Institutions (RCMI)—Center for Environmental Health (NIH-NCRR G12RR13459-15 and NIH-NIMHD 8G12MD007581-15).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: BSW, RDI, BLG. Analyzed the data: BSW, BLG, SSS, WKA, ALH, ANM, COB, RDI. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: BLG, BSW, RDI, WKA. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: RDI, BLG, BSW. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: BSW, BLG, SSS, WKA, ALH, ANM, COB, RDI. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: BSW, BLG, SSS, WKA, ANM, RDI. Made critical revisions and approved final version: BSW, RDI. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

Author(s) disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosures and Ethics

As a requirement of publication author(s) have provided to the publisher signed confirmation of compliance with legal and ethical obligations including but not limited to the following: authorship and contributorship, conflicts of interest, privacy and confidentiality and (where applicable) protection of human and animal research subjects. The authors have read and confirmed their agreement with the ICMJE authorship and conflict of interest criteria. The authors have also confirmed that this article is unique and not under consideration or published in any other publication, and that they have permission from rights holders to reproduce any copyrighted material. Any disclosures are made in this section. The external blind peer reviewers report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Guinebretiere MH, Auger S, Galleron N, et al. Bacillus cytotoxicus sp. nov. is a new thermotolerant species of the Bacillus cereus group occasionally associated with food poisoning. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012 Feb 17; doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.030627-0. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koehler TM. Bacillus anthracis genetics and virulence gene regulation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;271:143–64. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-05767-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovacs AT, van HM, Kuipers OP, van KR. Genetic tool development for a new host for biotechnology, the thermotolerant bacterium Bacillus coagulans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:4085–8. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03060-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roh JY, Choi JY, Li MS, Jin BR, Je YH. Bacillus thuringiensis as a specific, safe, and effective tool for insect pest control. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;17:547–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vary PS, Biedendieck R, Fuerch T, et al. Bacillus megaterium—from simple soil bacterium to industrial protein production host. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;76:957–67. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson WL, Munakata N, Horneck G, Melosh HJ, Setlow P. Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:548–72. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.3.548-572.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenquist H, Smidt L, Andersen SR, Jensen GB, Wilcks A. Occurrence and significance of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis in ready-to-eat food. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005 Sep 1;250(1):129–36. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faille C, Jullien C, Fontaine F, et al. Adhesion of Bacillus spores and Escherichia coli cells to inert surfaces: role of surface hydrophobicity. Can J Microbiol. 2002;48:728–38. doi: 10.1139/w02-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guidi V, Patocchi N, Luthy P, Tonolla M. Distribution of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis in Soil of a Swiss Wetland reserve after 22 years of mosquito control. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:3663–8. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00132-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kvint K, Nachin L, Diez A, Nystrom T. The bacterial universal stress protein: function and regulation. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:140–5. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hingley-Wilson SM, Lougheed KE, Ferguson K, Leiva S, Williams HD. Individual Mycobacterium tuberculosis universal stress protein homologues are dispensable in vitro. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2010;90:236–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isokpehi RD, Simmons SS, Cohly HH, et al. Identification of drought-responsive universal stress proteins in viridiplantae. Bioinform Biol Insights. 2011;5:41–58. doi: 10.4137/BBI.S6061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schweikhard ES, Kuhlmann SI, Kunte HJ, Grammann K, Ziegler CM. Structure and function of the universal stress protein TeaD and its role in regulating the ectoine transporter TeaABC of Halomonas elongata DSM 2581(T) Biochemistry. 2010;49:2194–204. doi: 10.1021/bi9017522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isokpehi RD, Mahmud O, Mbah AN, et al. Developmental Regulation of Genes Encoding Universal Stress Proteins in Schistosoma mansoni. Gene Regul Syst Bio. 2011;5:61–74. doi: 10.4137/GRSB.S7491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gury J, Seraut H, Tran NP, et al. Inactivation of PadR, the repressor of the phenolic acid stress response, by molecular interaction with Usp1, a universal stress protein from Lactobacillus plantarum, in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:5273–83. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00774-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zarembinski TI, Hung LW, Mueller-Dieckmann HJ, et al. Structure-based assignment of the biochemical function of a hypothetical protein: a test case of structural genomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15189–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sousa MC, McKay DB. Structure of the universal stress protein of Haemophilus Influenzae. Structure. 2001;9:1135–41. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00680-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernhardt J, Weibezahn J, Scharf C, Hecker M. Bacillus subtilis during feast and famine: visualization of the overall regulation of protein synthesis during glucose starvation by proteome analysis. Genome Res. 2003;13:224–37. doi: 10.1101/gr.905003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kruger S, Gertz S, Hecker M. Transcriptional analysis of bglPH expression in Bacillus subtilis: evidence for two distinct pathways mediating carbon catabolite repression. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2637–44. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2637-2644.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida K, Sano H, Seki S, et al. Cloning and sequencing of a 29 kb region of the Bacillus subtilis genome containing the hut and wapA loci. Microbiology. 1995;141(Pt 2):337–43. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-2-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noback MA, Holsappel S, Kiewiet R, et al. The 172 kb prkA-addAB region from 83 degrees to 97 degrees of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome contains several dysfunctional genes, the glyB marker, many genes encoding transporter proteins, and the ubiquitous hit gene. Microbiology. 1998;144(Pt 4):859–75. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-4-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antelmann H, Scharf C, Hecker M. Phosphate starvation-inducible proteins of Bacillus subtilis: proteomics and transcriptional analysis. J Bacteriology. 2000;182:4478–90. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.16.4478-4490.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markowitz VM, Chen IM, Palaniappan K, et al. IMG: the Integrated Microbial Genomes database and comparative analysis system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D115–22. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siefert JL, Larios-Sanz M, Nakamura LK, et al. Phylogeny of marine Bacillus isolates from the Gulf of Mexico. Curr Microbiol. 2000;41:84–8. doi: 10.1007/s002840010098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caspi R, Altman T, Dreher K, et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D742–53. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchler-Bauer A, Lu S, Anderson JB, et al. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D225–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang R, Ziemkiewicz C, Green TM, Ribarsky W. Defining insight for visual analytics. IEEE Comput Graph Appl. 2009;29:14–7. doi: 10.1109/mcg.2009.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson MO, Cohly HH, Isokpehi RD, Awofolu OR. The case for visual analytics of arsenic concentrations in foods. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:1970–83. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7051970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simmons SS, Isokpehi RD, Brown SD, et al. Functional Annotation Analytics of Rhodopseudomonas palustris Genomes. Bioinform Biol Insights. 2011;5:115–29. doi: 10.4137/BBI.S7316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sims JN, Isokpehi RD, Cooper GA, et al. Visual analytics of surveillance data on foodborne vibriosis, United States, 1973–2010. Environ Health Insights. 2011;5:71–85. doi: 10.4137/EHI.S7806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harvie DR, Vilchez S, Steggles JR, Ellar DJ. Bacillus cereus Fur regulates iron metabolism and is required for full virulence. Microbiology. 2005;151:569–77. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hussain M, Carlino A, Madonna MJ, Lampen JO. Cloning and sequencing of the metallothioprotein beta-lactamase II gene of Bacillus cereus 569/H in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriology. 1985;164:223–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.1.223-229.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rensing C. Form and function in metal-dependent transcriptional regulation: dawn of the enlightenment. J Bacteriology. 2005;187:3909–12. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.12.3909-3912.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bunk B, Schulz A, Stammen S, et al. A short story about a big magic bug. Bioeng Bugs. 2010;1:85–91. doi: 10.4161/bbug.1.2.11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu L, Li Y, Zhang J, et al. Complete genome sequence of the industrial strain Bacillus megaterium WSH-002. J Bacteriology. 2011;193:6389–90. doi: 10.1128/JB.06066-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eppinger M, Bunk B, Johns MA, et al. Genome sequences of the biotechnologically important Bacillus megaterium strains QM B1551 and DSM319. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:4199–213. doi: 10.1128/JB.00449-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott JW, Hawley SA, Green KA, et al. CBS domains form energy-sensing modules whose binding of adenosine ligands is disrupted by disease mutations. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:274–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI19874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakamura H, Saiki K, Mogi T, Anraku Y. Assignment and functional roles of the cyoABCDE gene products required for the Escherichia coli bo-type quinol oxidase. J Biochem. 1997;122:415–21. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blander G, Guarente L. The Sir2 family of protein deacetylases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:417–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schug TT, Li X. Sirtuin 1 in lipid metabolism and obesity. Ann Med. 2011;43:198–11. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.547211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Starai VJ, Celic I, Cole RN, Boeke JD, Escalante-Semerena JC. Sir2-dependent activation of acetyl-CoA synthetase by deacetylation of active lysine. Science. 2002;298:2390–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1077650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li X, Kazgan N. Mammalian sirtuins and energy metabolism. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7:575–87. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kanfi Y, Naiman S, Amir G, et al. The sirtuin SIRT6 regulates lifespan in male mice. Nature. 2012;483:218–21. doi: 10.1038/nature10815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alhazzazi TY, Kamarajan P, Joo N, et al. Sirtuin-3 (SIRT3), a novel potential therapeutic target for oral cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:1670–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanno M, Kuno A, Horio Y, Miura T. Emerging beneficial roles of sirtuins in heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012(107):273. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0273-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gardner JG, Escalante-Semerena JC. In Bacillus subtilis, the sirtuin protein deacetylase, encoded by the srtN gene (formerly yhdZ), and functions encoded by the acuABC genes control the activity of acetyl coenzyme A synthetase. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:1749–55. doi: 10.1128/JB.01674-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.North BJ, Sinclair DA. Sirtuins: a conserved key unlocking AceCS activity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han CS, Xie G, Challacombe JF, et al. Pathogenomic sequence analysis of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis isolates closely related to Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriology. 2006;188:3382–90. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.9.3382-3390.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mansilla MC, de MD. The Bacillus subtilis cysP gene encodes a novel sulphate permease related to the inorganic phosphate transporter (Pit) family. Microbiology. 2000;146(Pt 4):815–21. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-4-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hullo MF, Auger S, Soutourina O, et al. Conversion of methionine to cysteine in Bacillus subtilis and its regulation. J Bacteriology. 2007;189:187–97. doi: 10.1128/JB.01273-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]