Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the deadliest solid cancers and represents the third leading cause of cancer-related death. There is a universal HCC male to female estimated ratio of 2.5, but the reason for this is not well understood. The Sleeping Beauty (SB) transposon system was used to elucidate candidate oncogenic drivers of HCC in a forward genetics screening approach. Gender bias occurrence was conserved in our model, with male experimental mice developing liver tumors at reduced latency and higher tumor penetrance. In parallel, we explored gender differences regarding genomic aberrations in 235 HCC patients. Liver cancer candidate genes were identified from both genders and genotypes. Interestingly, transposon insertions in the epidermal growth factor receptor (Egfr) gene were common in SB-induced liver tumors from male mice (10/10, 100%) but infrequent in female animals (2/9, 22%). Human SNP data confirmed that polysomy of chromosome 7, locus of EGFR, was more frequent in males (26/62, 41%) than females (2/27, 7%) (P = 0.001). Gene expression based Poly7 subclass patients were predominantly males (9/9) compared with 67% males (55/82) in other HCC subclasses (P = 0.02) and was accompanied by EGFR overexpression (P < 0.001). Gender bias occurrence of HCC associated with EGFR was confirmed in experimental animals using the SB transposon system in a reverse genetic approach. This study provides evidence for the role of EGFR in gender bias occurrences of liver cancer and as the driver mutational gene in the Poly7 molecular subclass of human HCC.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, gender bias, Sleeping Beauty, epidermal growth factor receptor, forward and reverse genetic screen

Introductory Statement

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer and third leading cause of cancer-related death (1). It is an aggressive tumor with dismal prognosis since less than 30% of patients will be eligible for potential curative treatment at the time of diagnosis (2). HCC is prevalent worldwide but differences in disease incidence rates reflect regional diversity mostly related to geographic distribution of viral hepatitis (2). Gender also influences risk with males showing a higher increase in prevalence over females, with limited existing preliminary molecular data that explains this gender discrepancy (3).

In order to screen for cancer-associated genes in different types of cancer using Sleeping Beauty (SB) transposons, conditional SB transposition systems have been successfully used to generate various solid tumors (4–6). As previously described, we used a hepatocyte-specific albumin (Alb) promoter driving Cre recombinase (Alb-Cre) transgene to activate transposase expression and initiate insertional mutagenesis specifically in the liver (5). As mutations in tumor protein p53 (TP53) are the most frequently described mutations in HCC, a conditional dominant negative transformation related protein 53 (Trp53) transgene was also included in the original screen (5, 7). Triple transgenic (transposition in a wild-type genetic background) and quadruple transgenic (transposition in a Trp53-deficient genetic background) mice from both genders were generated and aged for liver tumorigenesis.

In the present study, liver cancer-associated genes were identified from liver nodules isolated from different genders and genetic backgrounds using a conditional SB transposon forward insertional mutagenesis screen combined with the Roche 454 FLX high-throughput sequencing platform. Common insertion sites (CISs), representing regions of the genome with increased frequency of transposon integration than would be expected by random chance, indicate cancer-associated genes that confer selective growth advantage(s) to a cell. A revised and fully automated method for calculating common insertion sites based on Poisson distribution was used in this study (manuscript in press). Higher incidence of HCC was observed in male experiment animals, which corresponded with increased insertions in the Egfr locus in SB-induced HCCs from male mice (10/10, 100%) but infrequent in female experimental animals (2/9, 22%). Interestingly, when comparing the homologues of our CIS gene lists with 235 human HCC patients to determine gender bias differences, the most striking results were for EGFR with significant differences in copy number changes, representing the Poly7 molecular subclass of HCC previously described (8). Poly7 was more frequent in males than females and patients with EGFR copy number gains also had significantly higher EGFR mRNA levels compared to patients without gains. It is our hypothesis that EGFR is associated and/or involved with gender bias occurrences in HCC. Using SB in a reverse genetic manner, the gender bias nature of EGFR was confirmed using our in vivo mouse model as previously described (5, 9, 10). Furthermore, genetic information from human HCC data with in vivo validation, confirms the role of EGFR in gender disparities involved with human HCC.

Experimental Procedures

Generation of transgenic animals and PCR genotyping

Generation of transgenic animals and PCR genotyping for the identification of the various genotypes was performed as previously described (5).

Liver tumor analysis

Isolation of liver tumors for DNA and RNA extraction, processing for histological analysis were performed as previously described (5, 9).

Pyrosequencing

Protocol for amplicon sequencing using the GS20 Flex pyrosequencing machine was as previously described (5).

Selection criteria for common insertion sites (CISs)

Egfr PCR genotyping

PCR genotyping was used to confirm the presence of the T2/Onc transposon insertion in Egfr gene as previously described (5).

RT-PCR

Gene expression and copy number changes in human HCC samples

Vectors used for hydrodynamic injection

oPOSSUM analyses

Results

Hepatocyte-specific transposition and tumorigenesis

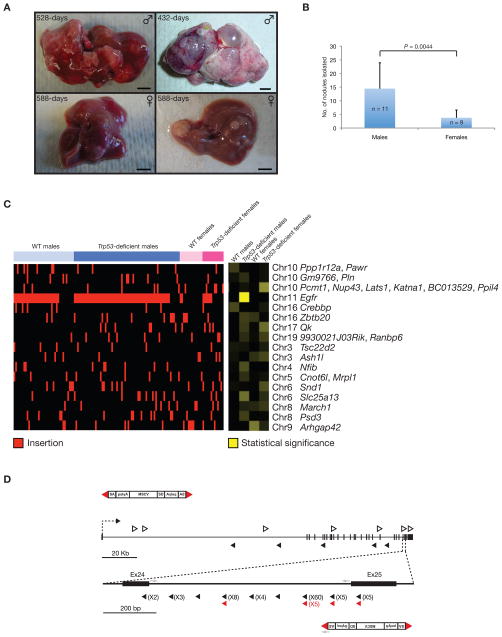

As shown previously, liver nodules were first detected at around 160-days in both triple transgenic male (transposition in a wild-type genetic background) and quadruple transgenic (transposition in a Trp53-deficient genetic background) animals (5). However, only insertion data in the quadruple transgenic mice was analyzed in the original study (5). In the present study, 61 liver nodules were isolated from triple transgenic male experimental mice (n = 5, ranging between 160- to 528-days) and genomic DNA was isolated for genetic interrogation to identify SB transposon insertions (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table 1). Triple transgenic male experimental mice (n = 3) also developed HCC between 330- and 528-days (Supplementary Table 1). Genetic insertion data of 68 liver nodules isolated from quadruple transgenic male mice (n = 5) previously described (5) were reanalyzed separately from the wild-type male liver nodules (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table 1). Quadruple transgenic male experimental mice (n = 4) also developed HCC between 156- and 432-days (Supplementary Table 1). Interestingly, the majority of liver nodules isolated from male experimental mice were histopathologically classified as HCCs (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Gender disparities seen in mouse model experimental animals with mutagenic SB-induced liver tumors. (A) HCC nodules in a 528-day old triple (top left) and 432-day old quadruple (top right) transgenic male experimental mice. Adenoma/HCC nodules in a 588-day triple (bottom left) and 588-day quadruple (bottom right) transgenic female experimental mice. Scale bars, 0.5 cm. (B) Statistical significantly higher number of liver nodules isolated from male (n = 11) than female (n = 9) experimental mice. P, unpaired t-test. (C) Top 17 candidate CIS genes from the combined analyses (P < 0.001) in Supplementary Table 7, shown as a heat map indicating putative gender bias genes responsible for HCC. Insertion within a CIS for a given tumor is indicated by the presence of a red bar. The gender and genotype are described in the bar above the heat map. Genes found in the neighborhood of the CISs are named to the right of the heat map. To determine whether gender bias occurrences of these CIS exist, Fisher’s exact statistical analysis of the relationship between insertion sites within CIS and phenotypes was performed. The result of this analysis is shown as a heat map (right heat map), where increase in intensity indicates higher statistical significance. P-values for associations are provided in Supplementary Table 7. (D) Diagrammatic representation of transposon insertions into the Egfr gene. Schematic representation of the mutagenic transposon (T2/Onc) is shown. Red triangles, inverted repeats/direct repeats (IR/DR) transposon flanking sequences; SA, splice acceptor; polyA, polyadenalytion signal; MSCV, LTR of the murine stem cell virus; SD, splice donor; open arrowhead, sense orientated insertion of the T2/Onc relative to the Egfr gene; arrowhead anti-sense orientated insertion of the T2/Onc relative to the Egfr gene; grey arrows, endogenous and vector primers used for PCR genotyping; numbers in parentheses, indicate the frequency of transposon insertions at each particular site from different liver tumor nodules of experimental animals; black and red arrowheads indicate transposon insertions in either male or female animals, respectively.

Triple and quadruple transgenic female experimental animals sacrificed from 178- to 342-days and 178- to 344-days, respectively, did not display any macroscopic liver lesions (5). In the current study, female triple transgenic and quadruple transgenic animals aged further did present liver nodules that were histopathologically classified as dysplastic lesions, adenomas or HCCs (Supplementary Table 1). The low frequency and late latency of liver nodules in female experimental animals mirrors the strong gender bias in tumor incidence seen in human HCC patients. In the present study, 20 liver nodules were isolated from triple transgenic female experimental mice (n = 6, ranging between 512- and 621-days) (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table 1) and 14 liver nodules were isolated from quadruple transgenic female experimental mice (n = 3, ranging between 432- and 624-days) (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table 1) for genetic interrogation to identify SB transposon insertions. There was a statistical significantly higher number of liver nodules isolated from male experimental mice (P = 0.0044), indicating gender bias occurrence of HCC was also observed in our mouse model (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table 1).

Sequencing for common insertion sites (CISs) from tumor samples

From triple transgenic male mice, 4,111 non-redundant insertions were subsequently cloned from 61 liver nodules identified 25 CIS loci harboring 27 annotated and 1 ENSMUST genes (Table 1). From quadruple transgenic male mice, 9,323 non-redundant insertions cloned from 68 liver nodules identified 18 CIS loci harboring 18 annotated and 2 GENSCAN predicted genes (Supplementary Table 2). When all male samples were combined, 47 CIS loci were identified harboring 70 annotated and 1 GENSCAN genes (Supplementary Table 3). From triple transgenic female mice, 1,819 non-redundant insertions cloned from 20 liver nodules identified 17 CIS loci harboring 22 annotated and 1 GENSCAN genes (Supplementary Table 4). Subsequently, from quadruple transgenic female mice, 1,750 non-redundant insertions cloned from 14 liver nodules identified 12 CIS loci harboring 16 annotated genes (Supplementary Table 5). When all female samples were combined, 42 CIS loci were identified harboring 50 annotated, 1 RIKEN and 1 GENSCAN predicted genes (Supplementary Table 6). In order to obtain an overall genetic landscape profiling, non-redundant insertions from both genders and genetic backgrounds were pooled for analysis. This identified 83 CIS loci harboring 114 annotated and 2 RIKEN genes that can provide useful genetic mechanisms associated with the strong gender bias nature of this deadly disease (Supplementary Table 7). Out of the 83 CIS loci identified in this screen, 11 CISs were previously identified in the original screen using predominantly male quadruple transgenic mice (5) (Supplementary Table 7).

Table 1.

Common insertion sites for HCC-associated genes in wild-type males

| Gene | Chr | Start | End | Range (bp) | P value | Frequency | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egfr | 11 | 16809300 | 16833300 | 24000 | 3.91E-06 | 28 | 5 |

| Crebbp | 16 | 4126000 | 4204000 | 78000 | 2.89E-05 | 5 | 2 |

| Ppp1r12a | 10 | 107647400 | 107671400 | 24000 | 0.000474431 | 4 | 3 |

| Kif1b | 4 | 148604000 | 148628000 | 24000 | 0.000474431 | 4 | 1 |

| BC031353 | 9 | 74820700 | 74844700 | 24000 | 0.000474431 | 3 | 1 |

| Rbm10 | X | 20201300 | 20225300 | 24000 | 0.000474431 | 5 | 2 |

| Rabgap1l | 1 | 162423600 | 162709600 | 286000 | 0.003442505 | 7 | 4 |

| Ctnna1 | 18 | 35320400 | 35344400 | 24000 | 0.04604139 | 3 | 2 |

| Ppp2ca | 11 | 51915000 | 51939000 | 24000 | 0.04604139 | 3 | 2 |

| Lsamp | 16 | 40005000 | 40029000 | 24000 | 0.04604139 | 3 | 2 |

| ENSMUST00000071374 | 17 | 17087700 | 17111700 | 24000 | 0.04604139 | 3 | 2 |

| Usp34 | 11 | 23346000 | 23370000 | 24000 | 0.04604139 | 3 | 2 |

| Gm9766 | 10 | 53077500 | 53101500 | 24000 | 0.04604139 | 3 | 3 |

| Nbeal1 | 1 | 60261800 | 60285800 | 24000 | 0.04604139 | 3 | 2 |

| Tsc22d2 | 3 | 58242100 | 58266100 | 24000 | 0.04604139 | 3 | 2 |

| Rere | 4 | 149883900 | 149907900 | 24000 | 0.04604139 | 3 | 1 |

| Palld | 8 | 64026800 | 64050800 | 24000 | 0.04604139 | 3 | 2 |

| Arih1 | 9 | 59245100 | 59269100 | 24000 | 0.04604139 | 3 | 2 |

| Arih2 | 9 | 108526300 | 108550300 | 24000 | 0.04604139 | 4 | 2 |

| Pard3 | 8 | 129757600 | 129835600 | 78000 | 0.048242492 | 4 | 3 |

| Btbd7 | 12 | 104069000 | 104147000 | 78000 | 0.048242492 | 4 | 3 |

| Smap1 | 1 | 23864600 | 23942600 | 78000 | 0.048242492 | 5 | 4 |

| Dpyd | 3 | 118304800 | 118590800 | 286000 | 0.049060679 | 6 | 3 |

| Phf21a, Pex16 | 2 | 92057800 | 92224800 | 167000 | 0.049906281 | 5 | 2 |

| Atn1, Usp5, Lpcat3 | 6 | 124624400 | 124791400 | 167000 | 0.049906281 | 5 | 2 |

Chr, chromosome; Start, start position of transposon insertions; End, end position of transposon insertions; Range, chromosomal position of transposon insertions; Frequency, number of preneoplastic nodules from which the CIS was determined from; n, number of mice from which the nodules were isolated from. Position based on the Ensembl NCBI m37 April 2007 mouse assembly.

Combined insertion profiles

Transposon insertion data from both gender and all genotypes (16,977 non-redundant) were combined in order to obtain an overall relationship between gender/genotype and insertion sites (Supplementary Table 7). Relationships between the insertions and the tumor libraries for the most statistically significant CISs (P < 0.001) are shown (Fig. 1C). The insertion profiles for all 163 samples were sorted by gender and genotype (Fig. 1C, left heat map). Fisher’s exact test was performed on all insertion sites in order to determine whether gender bias occurrences of these CISs exist. The result of this analysis is shown as a heat map (Fig. 1C, right heat map). From the statistical analytical heat map, there are clusters of genes that are clearly enriched or absent in liver nodules from both genders and genotypes. These clusters indicate putative gender bias genes responsible for HCC.

Frequent transposon insertions in Egfr for male liver nodules

As seen previously in quadruple transgenic males (5), transposon insertions in the Egfr gene also represented the most frequently hit gene in triple transgenic male experimental animals. Although Egfr insertions were cloned from all triple transgenic male experimental animals (n = 5), these insertions were only detected in 46% of liver nodules (n = 61) (Table 1). These transposon insertions were most frequently detected in intron 24 of Egfr and the majority of insertions were in the antisense orientation, suggesting they are Egfr-truncating insertions. Most strikingly, Egfr insertions in combined male mice were detected in all mice (n = 10) and at a frequency of 67% total liver nodules (n = 129) (Supplementary Table 3). In contrast, Egfr insertions were detected in 33% of quadruple transgenic female mice (n = 3) and 17% of triple transgenic female mice (n = 6). Egfr insertions in combined female mice were only detected in 22% of mice (n = 9) and at a frequency of 24% total liver nodules (n = 34) (Supplementary Table 6). Therefore, Egfr alterations are more commonly found in male mice tumors suggesting a contribution to the gender bias nature of HCC (Fig. 1D).

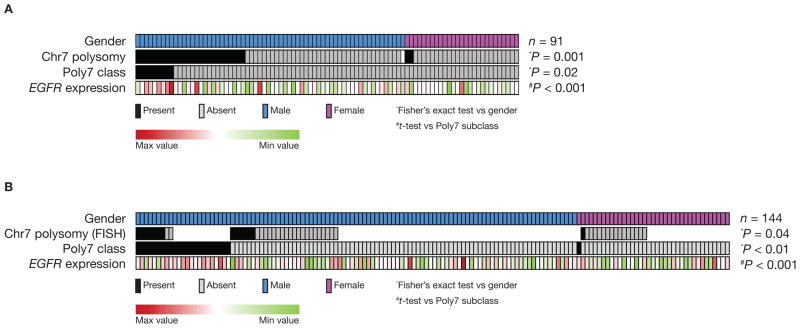

Gender disparities in human HCC

Among the 91 human HCCs analyzed (training set), there were 70% (n = 64) males and 30% females (n = 27). As an initial step, we analyzed the distribution of males and females amongst our previously reported human HCC molecular subclasses (8). Interestingly, Poly7 subclass patients were all males (9/9) compared with 67% males (55/82) in other HCC subclasses (P = 0.02) (Fig. 2A and Table 2). EGFR mRNA levels were higher in tumors belonging to this Poly7 subclass of HCC (P < 0.001), which is characterized by gains in chromosome 7 (locus of EGFR in humans) (8) (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Data 4). According to our observations, polysomy of chromosome 7 occurred more frequently in men than in women (26/63 males versus 2/27 females, P = 0.001) (Fig. 2A and Table 2). Gender distribution was analyzed in a second independent dataset of 144 FFPE HCC (validation set) including 107 males (74%) and 37 females (26%). In this set, Poly7 subclass also showed male gender bias [96% (23/24) of Poly7 subclass were males versus 70% (84/120) in the others subclasses, P < 0.01 (Fig. 2B and Table 2)]. Overall in the combined human dataset (training plus validation), we observed a male to female ratio of 33:1 in the Poly7 subclass, as opposed to a ratio of 2:1 in the non-Poly7 samples. As DNA copy number data was not available for the validation set, FISH analysis using a probe specific for the centromeric region of human chromosome 7 probe was applied to 51 samples. FISH analysis revealed that patients belonging to the Poly7 subclass significantly showed chromosome 7 polysomy (7/9 in the Poly7 subclass versus 7/42 in other subclasses, P < 0.001). Also in this subset it was observed that polysomy of chromosome 7 occurred more frequently in men than in women (13/35 men versus 1/16 women, P = 0.04) (Fig. 2B and Table 2). Finally, EGFR over-expression in Poly7 subclass samples was confirmed in the validation set (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Data 5).

Figure 2.

Poly7 subclass accounts for gender disparities seen in human hepatocarcinogenesis. (A) Heat map showing previously identified Poly7 molecular subclass in the HCC training set (n = 91). Polysomy of chromosome 7 was enriched in patients of this subgroup (P = 0.02), as well as EGFR mRNA levels were higher in these tumors (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Data 4). (B) Heat map showing samples belonging to Poly7 subclass within the validation set (n = 144). EGFR mRNA over-expression and polysomy of chromosome 7 were significantly enriched in patients of the Poly7 subclass (Supplementary Data 5). (A and B) Patients belonging to Poly7 subclass are indicated in black and other classes in gray. Presence or absence of chromosome 7 polysomy as indicated: present (black box), absent (gray box) or missing (white box) data. EGFR gene expression level is represented as indicated in color scale.

Table 2.

Chromosome 7 polysomy and Poly7 molecular subclass gender bias in human HCC

| Training set | Validation set | Combined | *P | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Male (n) | Female (n) | Male (n) | Female (n) | Male (n) | Female (n) | |||||

| All in cohort | 64 | 27 | 91 | 107 | 37 | 144 | 171 | 64 | 235 | |

| Poly7 subclass | 9 | 0 | 9 | 23 | 1 | 24 | 32 | 1 | 33 | |

| Non-Poly7 subclass | 55 | 27 | 82 | 84 | 36 | 120 | 139 | 63 | 202 | < 0.001 |

| Chr7 poly (SNP or FISH) | 26 | 2 | 28 | 13 | 1 | 14 | 39 | 3 | 43 | |

| No Chr7 poly (SNP or FISH) | 37 | 25 | 62 | 22 | 15 | 37 | 59 | 40 | 99 | < 0.001 |

Chr7 poly, polysomy of chromosome 7; Poly7, Poly7 molecular subclass of HCC; Non-Poly7, other molecular subclasses of HCC; SNP, gene copy number determined by SNP-array; FISH, gene copy number determined by fluorescent in situ hydridization using a probe specific for the centromeric region of human chromosome 7; Combined, training plus validation sets;

P, Fisher’s exact test versus gender in the combined training plus validation dataset.

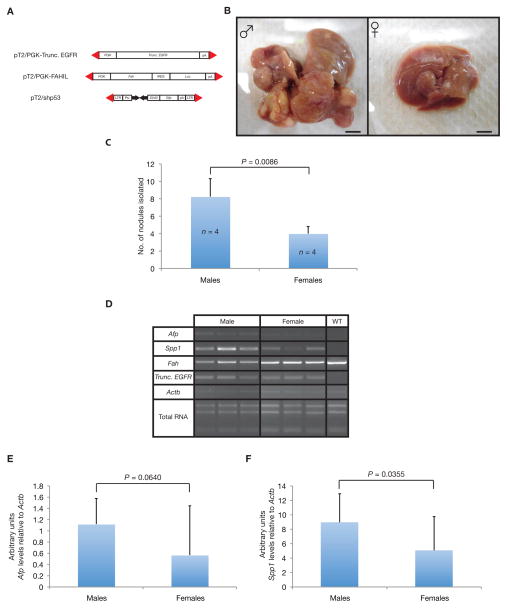

Validation of EGFR in gender disparities involved with liver tumorigenesis

To test whether EGFR could contribute to neoplastic growth in vivo specifically in a gender bias manner, the fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (Fah)-deficient mouse model was utilized as previously described (9, 10). SB transposon-based expression vector for the truncated EGFR (pT2/PGK-Trunc. EGFR), full-length EGFR (pT2/PGK-EGFR), source of Fah (pT2/PGK-FAHIL) and a short-hairpin RNA vector directed against the Trp53 gene (pT2/shp53) were co-administered to both genders of Fah-deficient mice that express the SB11 transposase knocked into the Rosa26 locus (Fah/SB11) by tail vein hydrodynamic injection (5, 11) (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. 1A). Upon withdrawal of NTBC, the mice underwent liver repopulation, as evidenced by stable weight gain and increasing Luciferase expression (data not shown). At around 130-days post-hydrodynamic injection (PHI), both gender Fah/SB11 mice co-administered with either truncated or full-length EGFR, source of Fah and a short-hairpin RNA vector directed against the Trp53 gene were sacrificed and observed for liver nodules. Interestingly for truncated EGFR, pT2/PGK-FAHIL and pT2/shp53 co-injected mice, male Fah/SB11 mice (n = 9) had significantly increased number of liver nodules compared with female mice (n = 4) (P = 0.0382) (data not shown). Striking differences in gender bias occurrences of HCC associated with EGFR can be seen in Fah/SB11 mice at 300-days PHI (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 1B). Male Fah/SB11 mice (n = 4) co-administered with pT2/PGK-Trunc. EGFR and pT2/shp53 had significantly increased number of liver tumor nodules compared with female mice (n = 4) (P = 0.0086) (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, liver tumors from both gender Fah/SB11 mice were classified as HCCs according to the histopathological analysis (data not shown). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analyses for several markers indicated that both short-hairpin against Trp53 (livers were GFP-positive due to the presence of the reporter gene in the plasmid construct, data not shown) and truncated EGFR vectors were being stably integrated into the mouse genome (Fig. 3D). Analysis of two known liver tumor markers, alpha fetoprotein (Afp) (P = 0.0640) (Fig. 3D) and secreted phosphoprotein 1 (Spp1) (P = 0.0355) (Fig. 3E) also indicated higher expression levels in males compared with female mice. Interestingly, this male gender bias was also observed with Fah/SB11 animals co-administered with pT2/PGK-EGFR and pT2/shp53 (P = 0.0388) (Supplementary Fig. 1C). Taken together, the genetic information from human HCC data with in vivo studies in Fah/SB11 mice validates the role of EGFR in gender disparities involved with human HCC.

Figure 3.

Validating the oncogenic gender bias potential of EGFR using the fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (Fah)-deficient/Rosa26-SB11 (Fah/SB11) mouse model. (A) Vectors used for hydrodynamic injections into the livers of Fah/SB11 mice. Truncated EGFR cDNA (exon 1 to exon 24) placed under the control of the phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter (pT2/PGK-Trunc. EGFR), Fah cDNA placed under the control of the PGK promoter fused with the IRES-Luciferase (Luc) reporter gene (pT2/PGK-FAHIL) and short-hairpin directed against Trp53 (pT2/shp53), all flanked by SB inverted repeat/direct repeat (IR/DR) recognition sequences essential for transposition (red triangles). (B) Representative macroscopic images of whole livers taken from male (left) and female (right) Fah/SB11 mice 300-days post-hydrodynamic injected (PHI) with pT2/PGK-Trunc. EGFR and pT2/shp53. Scale bars, 0.5 cm. (C) Significant increase in number of liver tumor nodules found in male versus female Fah/SB11mice hydrodynamically tail vein injected with pT2/PGK-Trunc. EGFR and pT2/shp53. Mice were sacrificed at 300-days PHI and liver tumor nodules counted. Mean ± standard deviation; P, unpaired t-test; n, number of mice. (D) Representative RT-PCR semi-quantitative analyses of various markers in livers taken from both 130-days PHI male and female Fah/SB11 mice injected with transgenes described in (A). Afp, alpha fetoprotein; Spp1, secreted phosphoprotein 1; Fah, fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase; Trunc. EGFR, truncated version of EGFR; Actb, β-actin; Total RNA, total RNA loading showing intact 28S, 18S and 5S ribosomal bands; WT, normal liver taken from a wild-type FVB/N mouse. (E) Arbitrary expression level of the liver tumor marker, Afp, relative to Actb was obtained using the NIH ImageJ showed a non-significant trend towards higher expression in male mice compared to female mice. (F) Arbitrary expression level of the liver tumor marker, Spp1, relative to Actb showed significantly higher expression in male mice compared to female mice. P, unpaired t-test.

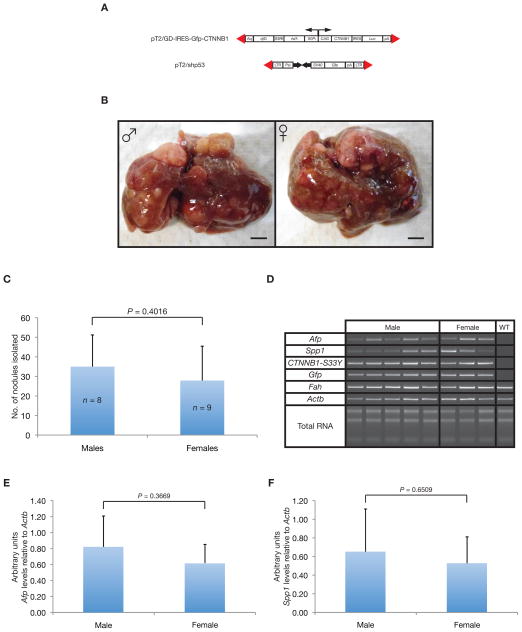

Gender has no effect on CTNNB1-driven liver tumorigenesis

As a control, a SB transposon-based expression vector for constitutively active catenin beta 1 (CTNNB1S33Y) transgene and pT2/shp53 were co-administered to both genders of Fah/SB11 mice (Fig. 4A). Upon withdrawal of NTBC, the mice underwent liver repopulation, as evidenced by stable weight gain and increasing Luciferase expression (data not shown). At around 80- and 83-days PHI, both gender Fah/SB11 mice co-administered with activated CTNNB1S33Y and a short-hairpin RNA vector directed against the Trp53 gene were sacrificed and observed for liver nodules (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, both male (n = 8) and female (n = 9) Fah/SB11 mice had comparable numbers of macroscopic liver tumors (P = 0.4016) (Fig. 4C). Liver tumors from both gender Fah/SB11 mice co-administered with activated CTNNB1S33Y and short-hairpin RNA vectors directed against the Trp53 gene developed were classified histologically as HCCs (data not shown). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analyses for several makers indicated that both short-hairpin against Trp53 and CTNNB1S33Y vectors were being stably integrated into the mouse genome (Fig. 4D). Analysis of liver tumor markers, Afp (P = 0.3669) (Fig. 4E) and Spp1 (P = 0.6509) (Fig. 4F) indicated comparable expression levels in both male and female mice. Taken together, overexpression of constitutively active CTNNB1 in the context of Trp53 knockdown did not induce strong gender bias occurrences of HCC.

Figure 4.

Validating the non-gender bias oncogenic potential of CTNNB1 in the Fah/SB11 mouse model. (A) Vectors carrying the constitutively active CTNNB1S33Y gene (pT2/GD-IRES-Gfp-CTNNB1) and pT2/shp53 delivered into the livers of Fah/SB11 mice by hydrodynamic injection. (B) Representative macroscopic images of whole livers taken from male (left) and female (right) Fah/SB11 mice injected mice 83-days post-hydrodynamic injected (PHI) with pT2/GD-IRES-Gfp-CTNNB1 and pT2/shp53. Scale bar, 0.5 cm. (C) Comparable number of liver tumor nodules found in both male and female Fah/SB11mice hydrodynamically tail vein injected with the vectors described in (A). Mice were sacrificed at 80- and 83-days PHI, and liver tumor nodules counted. Mean ± standard deviation; P, unpaired t-test; n, number of mice. (D) Representative RT-PCR semi-quantitative analyses of various markers in livers taken from both male and female Fah/SB11 mice injected with transgenes described in (A). CTNNB1-S33Y, constitutively active CTNNB1S33Y. (E) Arbitrary expression level of the liver tumor marker, Afp, relative to Actb showed similar expression level in both male and female mice. (F) Arbitrary expression level of the liver tumor marker, Spp1, relative to Actb showed similar expression level in both male and female mice. P, unpaired t-test.

Other gender bias genes identified in our SB mutagenesis screen

Male gender bias genes identified in our forward genetic screen included genes previously implicated in liver tumorigenesis from Trp53-deficient tumors. These genes were the solute carrier family 25 member 13 (Slc25a13), nuclear factor I/B (Nfib), partitioning-defective protein 3 (Pard3) and zinc finger and BTB domain containing 20 (Zbtb20) (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2A). Transposon insertion profiles in Slc25a13, Nfib and Pard3 indicate loss-of-function activities, while a gain-of-function activity is predicted for Zbtb20 (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR for Nfib and Pard3 expression in tumors with transposon insertions showed reduced transcript levels, consistent with the expected consequence of the transposon insertion pattern (Supplementary Fig. 2B and 2C). Transposon insertions in Zbtb20 were enriched upstream of the transcription start site, resulting in a predicted gain-of-function activity.

Female gender bias genes identified from combined genotypes include the NHL repeat containing 2 (Nhlrc2), Rho GTPase activating protein 42 (Arhgap42) and adenosine kinase (Adk) genes. Transposon insertion patterns in Nhlrc2 and Arhgap42 indicate gain-of-function activities, while a loss-of-function activity was predicted for Adk (Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Fig. 3).

Discussion

In this current study, we analyzed liver nodules isolated from both genders and different genetic backgrounds in order to elucidate the gender bias nature of HCC. Egfr insertions were enriched in male mice but infrequent in female experimental animals. Human data also confirmed that polysomy of chromosome 7 (locus of EGFR gene), occurred more frequently in males than females and was associated with EGFR overexpression. This gender bias occurrence of HCC associated with EGFR was confirmed in experimental animals using the SB transposon system in a reverse genetic manner.

Interestingly, transposon insertions in the Egfr gene that truncate the carboxy-terminus were common in SB-induced liver tumors from male mice but infrequent in female experimental animals (Fig. 1D). Activation of EGFR triggers signaling processesthat promote cell proliferation, migration, adhesion,angiogenesis, and inhibition of apoptosis (12). Carboxy-terminal domain deletions of EGFR (966-1006) result in higher autokinase activity and transforming ability (13). These naturally occurring EGFR deletion mutants display tumorigenic properties, probably resulting in constitutively active forms due to the destabilization of the inactive EGFR monomeric complex (13–16). EGFR is over-expressed in 15 to 40% of HCC although there are data suggesting activation of EGF signaling is actually higher (17, 18). Extra copies of the EGFR gene were seen in 45% of HCC tumors but increased expression did not correlate with the increase in EGFR copy number (19). Interestingly, analyses of human HCC indicate males are highly enriched in a molecular subclass (Poly7) that show chromosome 7 polysomy and over-expression of EGFR (8). Mechanisms that could explain the differential EGFR tumorigenic activity in males and females have been previously suggested (20). Genetic information from human HCC data with in vivo studies in Fah/SB11 mice validates the role of EGFR in gender disparities involved with human HCC. Interestingly, overexpression of full-length EGFR in Fah/SB11 mice also resulted in male gender bias occurrence of HCC (Supplementary Fig. 1). The CTNNB1 molecular subclass of human HCC has been shown to occur at similar frequency in both male and female patients (21, 22). The non-gender bias occurrence of HCC associated with the CTNNB1 molecular subclasss of HCC was confirmed using our Fah/SB11 mouse model (Fig. 4). Li et al. has recently demonstrated that Foxa1 and Foxa2 are essential for sexual dimorphism in liver cancer (23). Using hepatocyte-specific gene ablation, they were able to demonstrate that sexually dimorphic HCC was dependent on these Foxa genes that modulate the responses of sex hormones in HCC tumorigenesis. Using the oPOSSUM (version 3.0) web-based system (24, 25) for the detection of over-represented transcription factor binding sites in the promoters of our CIS genes (Supplementary Table 7), 39 transcription factors (including Foxa1 and Foxa2) were identified (using selection criteria of Z-score ≥10 and Fisher score ≥ 7) in 116 genes (Supplementary Data 1). Conserved Foxa1 and Foxa2 binding sites were identified near the transcription start site of the Egfr gene (Supplementary Data 2 and 3 for Foxa1 and Foxa2, respectively). From this in silico analysis, the results do suggest that our screen is indeed identifying genes and perhaps other transcription factors that may be involved in the gender bias occurrences of HCC.

In addition to EGFR, we have identified many other candidate genes involved with gender bias occurrences for this deadly disease. As shown previously, zinc finger and BTB domain containing 20 (Zbtb20) and solute carrier family 25 member 13 (Slc25a13) or citrin remain strong male gender bias cancer candidate genes (5). Interestingly, both Foxa1 and Foxa2 transcription binding sites were found to be over-represented in Zbtb20 and Slc25a13 by oPOSSUM analysis (Supplementary Data 2 and 3). Further examination of the transposon insertion profiles in Zbtb20 and Slc25a13 suggest a gain-of-function and loss-of-function activity, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Zbtb20 is a key regulator of Afp and is developmentally upregulated in postnatal liver (26). In addition, ZBTB20 expression is increased in human HCC and associated with poor prognosis (27). SLC25A13 gene mutations result in type II citrullinemia and mutations have been identified in male patients with non-viral HCC (28). Nuclear factor I/B (NFIB) has been shown to be direct functional targets of miR-372/373 and its knockdown promoted hepatitis-B viral expression (29). Partitioning-defective protein 3 (Pard3) is an adapter protein involved in asymmetrical cell division, cell polarization and plays a role in the formation of epithelial tight junctions. Our preliminary validation seems to indicate that both Nfib and Pard3 as novel candidate tumor suppressor genes for liver tumorigenesis (Supplementary Fig. 2A to 2C). Candidate genes identified in our screen to be female gender bias include the NHL repeat containing 2 (Nhlrc2), Rho GTPase activating protein 42 (Arhgap42) and adenosine kinase (Adk) genes (Supplementary Fig. 3). Interestingly, both Foxa1 and Foxa2 transcription binding sites were found to be over-represented in all three genes by oPOSSUM analysis (Supplementary Data 2 and 3). Transposon insertion pattern into Nhlrc2 and Arhgap42 predict a gain-of-function, indicating these two genes are putative oncogenes. In contrast, transposon insertion pattern for Adk predicts a loss-of-function activity and a putative tumor suppressor gene. Interestingly, disruption of Adk results in neonatal hepatic steatosis (30) and perturbs the methionine cycle resulting in hypermethioninemia, encephalopathy and abnormal liver function (31). Taken together, we are only in the beginning of unraveling the complex molecular mechanisms behind gender disparities in HCC. Although some evidence has been implicated between the role of sex hormones and modulation of gene expression through FOXA transcription factors, further studies are needed to define the implication of sexual hormones in the molecular pathogenesis of HCC.

This study provides convincing evidence for the role of EGFR in gender disparities and as the driver mutational gene in the Poly7 molecular subclass of human HCC. In addition, we have established two mouse models that recapitulate two of the molecular subclasses of human HCC, namely Poly7 and CTNNB1. This study also highlights other candidates through the use of the SB forward insertional mutagenesis system that could account for the gender disparities found between male and female HCC patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute for providing extensive computational resources (hardware and systems administration support) used to carry out the sequence analysis. We are also thankful to A.J.D. for trying to bring us closer to “gCIS”.

Financial Support

J.M.L. is supported by the U.S. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1R01DK076986-01), European Comission-FP7 Framework (HEPTROMIC, Proposal No: 259744), The Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, the Spanish National Health Institute (SAF-2010-16055), and the Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer. D.A.L. is supported by U01 CA84221 and R01 CA113636 grants from the National Cancer Institute.

List of Abbreviations

- CIS

common insertion site

- FFPE

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- lsl

LoxP-stop-LoxP cassette

- NTBC

2-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethylbenzoyl)-1,3-cyclohexanedione

- PHI

post-hydrodynamic injection

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, Maeda S, Kim K, Elsharkawy AM, Karin M. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science. 2007;317:121–124. doi: 10.1126/science.1140485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dupuy AJ, Rogers LM, Kim J, Nannapaneni K, Starr TK, Liu P, Largaespada DA, et al. A modified sleeping beauty transposon system that can be used to model a wide variety of human cancers in mice. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8150–8156. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keng VW, Villanueva A, Chiang DY, Dupuy AJ, Ryan BJ, Matise I, Silverstein KA, et al. A conditional transposon-based insertional mutagenesis screen for genes associated with mouse hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:264–274. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starr TK, Allaei R, Silverstein KA, Staggs RA, Sarver AL, Bergemann TL, Gupta M, et al. A transposon-based genetic screen in mice identifies genes altered in colorectal cancer. Science. 2009;323:1747–1750. doi: 10.1126/science.1163040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Vries A, Flores ER, Miranda B, Hsieh HM, van Oostrom CT, Sage J, Jacks T. Targeted point mutations of p53 lead to dominant-negative inhibition of wild-type p53 function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2948–2953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052713099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiang DY, Villanueva A, Hoshida Y, Peix J, Newell P, Minguez B, LeBlanc AC, et al. Focal gains of VEGFA and molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6779–6788. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keng VW, Tschida BR, Bell JB, Largaespada DA. Modeling hepatitis B virus X-induced hepatocellular carcinoma in mice with the Sleeping Beauty transposon system. Hepatology. 2011;53:781–790. doi: 10.1002/hep.24091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wangensteen KJ, Wilber A, Keng VW, He Z, Matise I, Wangensteen L, Carson CM, et al. A facile method for somatic, lifelong manipulation of multiple genes in the mouse liver. Hepatology. 2008;47:1714–1724. doi: 10.1002/hep.22195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell JB, Podetz-Pedersen KM, Aronovich EL, Belur LR, McIvor RS, Hackett PB. Preferential delivery of the Sleeping Beauty transposon system to livers of mice by hydrodynamic injection. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:3153–3165. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarden Y. The EGFR family and its ligands in human cancer. signalling mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37 (Suppl 4):S3–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang CM, Shu HK, Ravi L, Pelley RJ, Shu H, Kung HJ. A minor tyrosine phosphorylation site located within the CAIN domain plays a critical role in regulating tissue-specific transformation by erbB kinase. J Virol. 1995;69:1172–1180. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1172-1180.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landau M, Fleishman SJ, Ben-Tal N. A putative mechanism for downregulation of the catalytic activity of the EGF receptor via direct contact between its kinase and C-terminal domains. Structure. 2004;12:2265–2275. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boerner JL, Danielsen A, Maihle NJ. Ligand-independent oncogenic signaling by the epidermal growth factor receptor: v-ErbB as a paradigm. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frederick L, Wang XY, Eley G, James CD. Diversity and frequency of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in human glioblastomas. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1383–1387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villanueva A, Newell P, Chiang DY, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Genomics and signaling pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:55–76. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villanueva A, Chiang DY, Newell P, Peix J, Thung S, Alsinet C, Tovar V, et al. Pivotal Role of mTOR Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckley AF, Burgart LJ, Sahai V, Kakar S. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression and gene copy number in conventional hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:245–251. doi: 10.1309/WF10QAAED3PP93BH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Press OA, Zhang W, Gordon MA, Yang D, Lurje G, Iqbal S, El-Khoueiry A, et al. Gender-related survival differences associated with EGFR polymorphisms in metastatic colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3037–3042. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson MD, Monga SP. WNT/beta-catenin signaling in liver health and disease. Hepatology. 2007;45:1298–1305. doi: 10.1002/hep.21651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyault S, Rickman DS, de Reynies A, Balabaud C, Rebouissou S, Jeannot E, Herault A, et al. Transcriptome classification of HCC is related to gene alterations and to new therapeutic targets. Hepatology. 2007;45:42–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.21467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Z, Tuteja G, Schug J, Kaestner KH. Foxa1 and foxa2 are essential for sexual dimorphism in liver cancer. Cell. 2012;148:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho Sui SJ, Fulton DL, Arenillas DJ, Kwon AT, Wasserman WW. oPOSSUM: integrated tools for analysis of regulatory motif over-representation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W245–252. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho Sui SJ, Mortimer JR, Arenillas DJ, Brumm J, Walsh CJ, Kennedy BP, Wasserman WW. oPOSSUM: identification of over-represented transcription factor binding sites in co-expressed genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3154–3164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie Z, Zhang H, Tsai W, Zhang Y, Du Y, Zhong J, Szpirer C, et al. Zinc finger protein ZBTB20 is a key repressor of alpha-fetoprotein gene transcription in liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10859–10864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800647105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Q, Tan YX, Ren YB, Dong LW, Xie ZF, Tang L, Cao D, et al. Zinc finger protein ZBTB20 expression is increased in hepatocellular carcinoma and associated with poor prognosis. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:271. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang KW, Chen HL, Chien YH, Chen TC, Yeh CT. SLC25A13 gene mutations in Taiwanese patients with non-viral hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;103:293–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo H, Liu H, Mitchelson K, Rao H, Luo M, Xie L, Sun Y, et al. MicroRNAs-372/373 promote the expression of hepatitis B virus through the targeting of nuclear factor I/B. Hepatology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/hep.24441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boison D, Scheurer L, Zumsteg V, Rulicke T, Litynski P, Fowler B, Brandner S, et al. Neonatal hepatic steatosis by disruption of the adenosine kinase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6985–6990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092642899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bjursell MK, Blom HJ, Cayuela JA, Engvall ML, Lesko N, Balasubramaniam S, Brandberg G, et al. Adenosine kinase deficiency disrupts the methionine cycle and causes hypermethioninemia, encephalopathy, and abnormal liver function. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.