Abstract

This study reports methods for coating miniature implantable glucose biosensors with electrospun polyurethane (PU) membranes, their effects on sensor function and efficacy as mass-transport limiting membranes. For electrospinning fibres directly on sensor surface, both static and dynamic collector systems, were designed and tested. Optimum collector configurations were first ascertained by FEA modelling. Both static and dynamic collectors allowed complete covering of sensors, but it was the dynamic collector that produced uniform fibro-porous PU coatings around miniature ellipsoid biosensors. The coatings had random fibre orientation and their uniform thickness increased linearly with increasing electrospinning time. The effects of coatings having an even spread of submicron fibre diameters and sub-100μm thicknesses on glucose biosensor function were investigated. Increasing thickness and fibre diameters caused a statistically insignificant decrease in sensor sensitivity for the tested electrospun coatings. The sensors’ linearity for the glucose detection range of 2 to 30mM remained unaffected. The electrospun coatings also functioned as mass-transport limiting membranes by significantly increasing the linearity, replacing traditional epoxy-PU outer coating. To conclude, electrospun coatings, having controllable fibro-porous structure and thicknesses, on miniature ellipsoid glucose biosensors were demonstrated to have minimal effect on pre-implantation sensitivity and also to have mass-transport limiting ability.

Keywords: Electrospun coatings, implantable glucose biosensors, mass-transport limiting membranes, Selectophore™ polyurethane, FEA of electric-field distribution, static and dynamic collectors

1. Introduction

Polymeric coatings are commonly used as mechanical and chemical buffer zones at the sensor-tissue interface and are intended to prevent biofouling, fibrous encapsulation and blood vessel regression on the immediate surface of the implant [1-4]. However, it must be emphasised that any additional coatings on sensor surface would adversely affect sensor response sensitivity, even before they can be implanted in the body [2]. Hence, the design of such coatings should not only address the deleterious host tissue effects on sensor's in vivo function, but also minimise decrease in pre-implantation sensitivity. Here, we evaluated methods for electrospinning PU directly on miniature coil-type amperometric glucose biosensors and investigated their effects on sensor function. To our knowledge, towards the design of electrochemical biosensors, so far, electrospinning was used to develop electrodes having large surface to volume ratios [5], but not for coating miniature implantable glucose biosensors with fibro-porous mass-transport limiting or membranes for biocompatibility. The closest of such application was reported by Abidian and Martin, who used electrospinning to coat flat surfaces of neural electrodes with anti-inflammatory drug loaded biodegradable nano-fibers purely intended for drug delivery [6].

The sensing element of a basic implantable electrochemical glucose biosensor consists of an inner electrode (metal or carbon based), a middle enzyme layer (usually glucose oxidase) and an outer mass-transport limiting membrane (polymer). The latter layer often has the dual function of mass-transport limiting and that of outer coating for biocompatibility, for which solvent cast polymer coatings have been the gold standard. The materials tested include cellulose acetate (CA) [7, 8], poly(bisphenol A carbonate) (PC) [9], poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) [10], poly(tetrafluoroethylene-co-vinylidene fluoride-copropylene) [11], poly(4-vinylpyridine-co-styrene), Nafion [12], polydimethylsiloxane [7], polyallylamine-polyaziridine, polytetrafluoroethylene [4], poly(ethylene oxide), and polyurethane (PU) [13, 14]. Composite membranes e.g., CA-PC-PVC-PU and poly(hydroxyethyl methacrylate)-poly(dihydroxypropyl methacrylate)-N-Vinyl pyrrolidone-ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (HEMA-DHPMA-NVP-EGDMA) were also tested [14, 15]. Among the materials, PU membranes have been the most popular due to their durability, biocompatibility and long-term stability of sensor function in vitro [14, 16].

For mass-transport limiting, the membranes essentially are nano-porous, thus, have relatively flat surfaces. They assist long-term performance in vitro in buffers, but are not capable of functioning reliably upon implantation in the body for longer than a few hours to days [1, 17, 18]. Surface modifications with anti-fouling coatings such as, phosphorylcholine [19], 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine [20], PU with phospholipid polar groups [21], humic acids [22], hyaluronic acid [23], polyvinyl alcohol [24] were tested for preventing biofouling. Such coatings delay protein deposition immediately after implantation, but fail to prevent cell and fibrous tissue (barrier) layers’ formation within hours to days. Further studies indicated that nano-textured rather than smooth surfaces, often incorporating angiogenic or anti-inflammatory agents, are better in improving biocompatibility, which methods were reviewed by Vaddiraju et al. and Krishnan et al [18, 25]. Irrespective of these strategies, Brauker et al., suggest that a barrier cell layer that is compacted by inward force exerted by the fibrous capsule forms on the immediate surface of the sensors causing their failure in vivo [4]. Macro-porous scaffolds were suggested to prevent the compacting forces of fibrous capsules directly on the surface of the mass-transport limiting membrane, thus reducing the deleterious effects of the cell barrier layer [4]. Brauker et al. and Koschwanez et al. used macro-porous PDMS and polylactic acid solvent cast scaffolds respectively as an additional layer on sensors for improving biocompatibility [3, 4]. One such strategy is employed in the commercial DexCom Seven continuous glucose monitoring systems, the reliable clinical use of which is still limited to 7 days.

As mass-transport limiting and membranes for biocompatibility, electrospun membranes have strategic advantages over traditional solvent-cast polymer membranes. Firstly, they have excellent mechanical strength per unit volume. Secondly, their fibrous structure withstands longer elongation allowing them withstand outward pressure due to swelling of enzyme layer, without compromising on mechanical integrity. Thirdly, the electrospun fibres form better structural materials allowing them to withstand larger forces along the fibre length, thus minimizing mechanical weak spots. Fourth, they inherently have excellent interconnected porosity, predictable pore geometries and large pore volumes essential of sensors requiring analyte transport. Fifth, their fibro-porous structure mimics the natural extracellular matrix environment the host cells are accustomed to. Sixth, fibres composed of variety of structures, composition (including loading of drugs and other bioactive agents) and desired diameters can be designed to make them biomimetic, enabling the engineering of host responses to implanted sensors. Finally, in a single electrospinning step, thickness of the applied membrane can be controlled from tens of nano-meters to several micro-meters as desired.

In our earlier study, we demonstrated the ability to design electrospun Selectophore™ PU membranes having fibres of desired average diameters, and in turn, tailorable thickness, porosity, hydrophilicity, permeability to glucose and mechanical properties [26]. Following extensive parametric evaluation, we chose three electrospun membrane configurations having even spread of sub-micron to micron size fibre diameters, namely 347, 738 and 1102 nm, designated as 8PU, 10PU and 12PU respectively to study the effect of fibre diameter on physicochemical-, mechanical-properties, and trans-membrane permeability to glucose. The typical properties of 8PU, 10PU and 12PU membranes electrospun on flat-plate collector are summarised in Table 1 [26]. The hypothesis for the current study was that electrospun polymer membranes, due to their unique fibro-porous structure having interconnected pores and high porosity (40 to 70%) would have minimal effect on sensor response sensitivity in vitro. To this goal we first evaluated methods to electrospin fibres directly on the surface of a model coil-type electrochemical implantable glucose biosensor and investigated the coatings’ effects on sensor function.

Table 1.

Summary of structure and physical properties of the base electrospun PU membranes used in this study, namely 8PU, 10PU and 12PU electrospun on flat-plate collector. The electrospinning parameters are summarised in Table 2, with the exception that the fibres were spun on to a flat stainless steel plate. The designations of membranes are based on the feed solution concentration of polyurethane solution and total duration of continuous electrospinning, e.g., 8PU-5’ indicate membrane spun using 8% PU solution for 5 minutes, Data expressed as mean ± SD.

| Sample | Fibre Diameter (nm) | Thickness (μm) | Pore volume (%) | Average pore size (nm) | Contact angle (o) | Diffusion coefficient for glucose (mm2/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU film | - | - | - | - | 86 | - |

| 8PU-5’ | 347±87 | 15.6±2.65 | - | - | - | (1.79±0.10) × 10-4 |

| 8PU-120’ | 28.4±5.4 | 44.19±2.54 | 800 | 104 | - | |

| 10PU-5’ | 738±131 | 19.0±4.04 | - | - | - | (1.49±0.13) × 10-4 |

| 10PU-120’ | 86.0±12.9 | 62.87±1.18 | 870 | 116 | - | |

| 12PU-5’ | 1102±210 | 21.5±4.14 | - | - | - | (2.01±0.41) × 10-4 |

| 12PU-120’ | 180.6±42.2 | 65.40±1.85 | 1060 | 123 | - |

2. Materials and Methods

Bovine serum albumin (BSA), glutaraldehyde grade I (50%) (GTA), glucose oxidase (GOD) (EC 1.1.3.4, Type X-S, Aspergillus niger, 157,500U/g, Sigma), ATACS 5104/4013 epoxy adhesive, Brij 30, Selectophore™ PU, Tetrahydrofunan (THF), N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), D-(+)-Glucose and 0.01M Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) tablets were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich–Fluka. Teflon-coated platinum–iridium (9:1 in weight, Ø 0.125mm) and silver wires (Ø 0.125mm) were procured from World Precision Instruments, Inc. (Sarasota, FL).

2.1. Glucose biosensor

A miniature coil-type implantable glucose biosensor, developed in Moussy's group [14-16], was modified and used as model sensor in this study. The amperometric sensor is a two electrode system based on Pt-Ir working and silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) reference electrodes.

Working electrode was prepared by first removing 1cm length of Teflon-coating at either ends of an 8cm long Pt-Ir wire. On one end, the bare Pt-Ir wire was wound around a 30 gauge needle (1/2inch, BD) to make the working electrode coil. The core of the coil was filled with cotton to enhance the immobilization of enzyme and prevent air bubble formation. The cotton reinforced coils were washed in DI water for 30min under continuous sonication followed by washing in ethanol for 20min.

For immobilizing GOD on the working electrode coil, about 2.5μl of the enzyme loading solution (39.3mg/ml BSA, 8.2mg/ml GOD and 1.6% (v/v) GTA (50%, v/v) dissolved in DI water) was coated on the cotton reinforced Pt-Ir coil and allowed to dry at room-temperature for 30min. This enzyme loading procedure was repeated for up to 4 times. After the last coating, the enzyme layer was left overnight to allow GTA crosslinking to complete.

Initially, to study the effect of epoxy-PU (EPU) membrane thickness, 1.5, 3, 6 and 12μl of the EPU loading solution (26.7mg of PU, 8.9mg each of Part A and Part B of epoxy adhesive and 1μl of Brij 30 dissolved in 4ml THF) was applied on the enzyme layer [16]. After air-drying at room temperature, the solvent cast EPU layer was cured at 80°C for 20 minutes. Thereafter, for studying the efficacy of electrospun coatings on sensor function, the base sensors were coated with a single 1.5μl coating of epoxy-PU (EPU) mass-transport limiting membrane.

The reference electrode was prepared by stripping 1cm of Teflon coating from each end of a 7cm long Teflon coated silver wire. One end was carefully wound around a 30 gauge 1/2inch hypodermic needle to obtain the coil end. The Ag coil was treated with ammonia solution for 30sec followed by 10sec in 6M nitric acid. The coil was then washed in DI water and electroplated in 0.01M HCl at a constant current of 0.1mA using a galvanostat (263A, Princeton Applied Research, TN, US) overnight. The resulting Ag/AgCl reference electrode coils were rinsed with DI water. The sensors were assembled by inserting the Pt-Ir wire of working electrode through the coil of reference electrode until the two electrodes were separated by 5mm and the Teflon-covered part of the two wires were intertwined along their entire length.

2.2. Electrospinning fibres directly on sensor surface

The electrospinning setup utilized for this study was manufactured at our workshop [26]. It was a vertical setup consisting of a 22G stainless steel needle as spinneret (BD, flat-tip, FISHMAN, UK) aligned perpendicularly above a grounded collector. A high voltage power supply (EL30R1.5, Glassman High Voltage Inc., Hampshire, UK) was used to charge high electrical potential between the spinneret and the collector. This basic vertical setup was enclosed in a transparent Plexiglass box equipped with a safety lock for protection from high voltages. Furthermore, a syringe pump (Fusion 100), also positioned inside the Plexiglass box, was used to pump polymer feed solution in a 10ml plastic syringe (BD), allowing a uniform, constant and stable mass flow through a PTFE tube (Ø 1/16’) connecting the syringe to the spinneret needle. For spinning fibres directly on the surface of miniature glucose biosensor, different collector configurations were evaluated. Initially, finite element analysis (FEA) simulations using Maxwell ® SV 2D software (Ansoft Corporation) were employed to identify an optimum static collector configuration (SCC). Thereafter, a dynamic collector configuration, wherein the sensor was rotated in the field of electrospinning, was tested.

The thin sensor wire was not rigid enough to be held in the electrospinning field opposite the spinneret needle. Hence, the length of the thin working electrode wire was inserted into a 1.5inch stainless steel needle (23G blunt-tip), such that the sensor's sensing element (working collector) along with about 5mm of its wire was exposed outside the tip of the holding needle for deposition of electrospun fibre.

2.2.1 FEA simulation for static collector configurations

Three FEA simulations were done using two static collector systems. First system designated as SCC-1 consisted of the sensor and its holding needle (23G), wherein the distance between the tip of the spinneret and the collecting sensor tip was 22cm and only the sensor was grounded. In the second static collector system (SCC-2 and SCC-3), the sensor and its holding needle were integrated vertically at the centre of a stainless steel plate. The plate and the sensor were grounded, wherein the plate was the auxiliary electrode. The distance between the spinneret tip and the tip of the sensing element was varied, 16cm for SCC-2 and 22 cm for SCC-3, to identify its effects on the strength of generated electric-field.

For the simulations, the different parameters, namely materials, applied voltages, medium, and boundary conditions were defined in the model. The material parameters were loaded from the software's materials database. An applied voltage of 21KV set on spinneret was used for all three simulations (SCC-1, SCC-2 and SCC-3), while 0KV was assigned on all grounded collectors. The medium wherein the spinneret and the collector system were held was defined as air. Assuming that no other electrical sources influence the electrospinning process, a balloon boundary was assigned to the background, which effectively means the electrospinning setup was electrically insulated. The finite element simulations were then automatically generated using the percent refinement per pass set at 45. A decrease in energy error after each adaptive pass was observed indicating the accuracy of the simulations. To obtain the capacitance matrix between the spinneret and collector systems, post simulation calculations were done using the ‘Setup Executive Parameters’ command of the Maxwell SV software.

The limitation for the simulations was that they were 2D. However, the 2D simulation can be considered as a planar slice through the three dimensional apparatus, so as to identify the optimum collector position and distance from the spinneret. The y-z plane that passes through the axis of the spinneret needle and the collector was chosen to model the electric-field distribution. Surface plots were used to show the spatial distribution and magnitude, while electric-field vector plots for direction and magnitude of the electric-field around and between the electrodes. The field strength is illustrated with a gradient of 25 colours from blue (minimum) to red (maximum). In addition to colour coding, the increasing vector arrow thickness and length also indicates increasing electric-field strength.

2.2.2 Dynamic collector

In the dynamic collector configuration, the sensor was rotated in electrospinning field. The sensor was inserted in 0.5inch stainless steel needle (23G blunt-tip) and the needle fixed at the end of a custom-made rotator. The rotator consisted of a mini motor and protective shield made of wood. The mini motor was driven by a low voltage power supply unit (Model: LA100.2, Coutant), whose rotation speed was calibrated using a stroboscope (RS components, UK) by systematically varying the voltage and current settings. A rotation speed between 660 – 690rpm, obtained by setting both voltage and current constant at 5V and 0.11A respectively, was chosen to obtain random orientation of the electrospun fibres.

2.3 Electrospinning parameters

The electrospinning parameters used for spinning PU membranes on flat-plate collector and directly on sensor surface are summarised in Table 2. The PU solution concentration (8, 10 and 12%) was varied to study the effect of fibre diameter and porosity on sensor function. Similarly, the electrospinning times were varied (2.5, 5 and 10min) to study the effect of thickness of electrospun coating (ESC). Furthermore, the fibro-porous PU membranes were electrospun both on sensors coated with epoxy-PU (EPU) mass-transport limiting membrane (Pt-GOD-EPU-ESC) and those without (Pt-GOD-ESC) to study the ability of electrospun membranes to function as mass-transport limiting membranes. The designations of the sensors, as presented in Table 2, are based on the final sensor configuration. For example, Pt-GOD-EPU-8PU indicates the concentric working electrode components from inside to out. Pt indicates Pt-Ir coil, GOD – immobilized glucose oxidase layer, EPU – epoxy polyurethane mass transport limiting membrane, and 8PU – electrospun membrane spun using 8% PU solution. In addition, to indicate the time of electrospinning a suffix, -2.5’, -5’ or -10’ is added to the designations in Table 2 (e.g., Pt-GOD-EPU-8PU-2.5’). To study the effect of different ESC configurations on sensor function, n=6 for each electrospun PU coating configuration were tested and 6 Pt-GOD-EPU or Pt-GOD sensors without any electrospun coatings as controls. The electrospinning was essentially processed at ambient conditions (23±3.32°C room temperature and 35 to 47% relative humidity). The electrospun membranes were dried for 24h at room temperature in a power assisted vacuum desiccator and then stored in a vacuum desiccator until further use.

Table 2.

Electrospinning conditions used for spinning PU fibres directly on biosensor surface. D is distance between spinneret tip and collecting sensor.

| Designation | Concentration (wt %) | Solvent THF:DMF (w/w) | Voltage (kV) | Feed rate (ml/h) | D (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt-GOD-EPU-8PU, Pt-GOD-8PU | 8 | 40:60 | 21 | 0.6 | 22 |

| Pt-GOD-EPU-10PU, Pt-GOD-10PU | 10 | 50:50 | 20 | 1.0 | 22 |

| Pt-GOD-EPU-12PU, Pt-GOD-12PU | 12 | 50:50 | 20 | 1.2 | 22 |

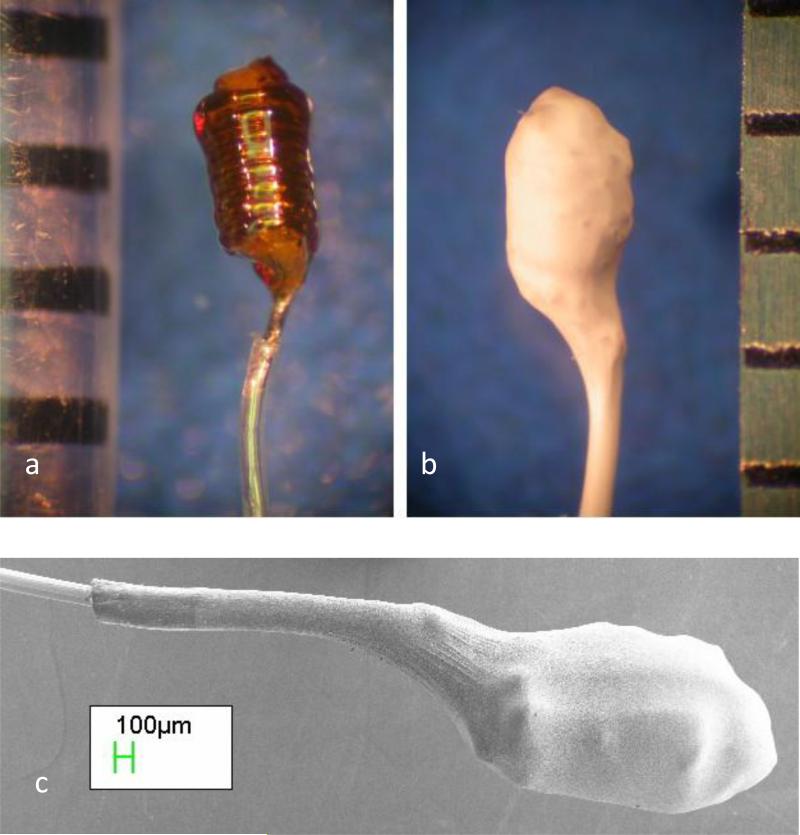

2.4 Characterization of electrospun membranes on glucose biosensors

2.4.1. Morphology

The quality of electrospun membranes being prepared was first screened visually under an optical microscope (LEICA S60) to ascertain the uniformity of the fibre being formed. Thereafter, morphology of small samples of the different electrospun membranes were sputter coated for 30 sec with gold using an AGAR high-resolution sputter-coater and observed under SEM (Zeiss Supra 35VP field emission SEM (FESEM) in SE mode).

2.4.2. Fibre Diameter and membrane thickness

The fibre diameters were measured on SEM images using a user friendly application developed using Matlab for length measurements. For each measurement, the software first requires a line to be drawn at one edge along the length of the fibre followed by a second line perpendicular to the first line drawn across to the other edge of the fibre to obtain the actual and the accurate measurement for fibre diameter. The accuracy of these measurements was cross-confirmed with Image J image analysis software. For the measurement of fibre diameter, a total of 160 measurements were made on 8 different SEM images, each representing a non-overlapping random field of view for each electrospun membrane configuration.

To obtain the fine cross section images for the electrospun membranes on sensors, they were snap-frozen using liquid nitrogen, followed by cutting using a scalpel. The resulting samples were processed for SEM and oriented appropriately to obtain image of cross-sections of the membranes. The above-mentioned software for length measurements was also used to measure the thicknesses of the membrane using SEM images captured showing their cross-sections. The effect of PU solution concentrations (8, 10 and 12%) on the thickness of the resulting electrospun membranes was evaluated.

2.5 Sensor function testing

2.5.1 Basic Test

Sensor function was tested by amperometric measurements of glucose in PBS using Apollo 4000 Amperometric Analyzer (World Precision Instruments Inc., Sarasota, FL) at 0.7V versus Ag/AgCl reference electrode as reported earlier [16]. The buffer solution was continuously stirred to ensure mixing of glucose in solution. Calibration plots for the sensors were obtained by measuring the current while increasing the glucose concentration from 0–30 mM (stepwise). The sensitivity (S) of each sensor was calculated using equation 1:

| (Eq. 1) |

where I15mM and I5mM are the steady state currents for 15 and 5mM glucose concentration respectively. All experiments were carried out at room temperature.

2.5.2 Effects of electrospun membrane coatings on sensor function and longevity

The best method for monitoring long-term performance of first generation glucose biosensors was reported to be the tracing of sensitivity rather than the response currents because the latter can be affected by the background current or the accumulated H2O2 in the enzyme layer [14, 27, 28]. We tested the long-term performance of the sensors in this study by intermittent measurements of sensor response sensitivity and linearity as described in section 2.5.1. For evaluating the effects of electrospun coatings on sensor function, the base sensors – Pt-GOD-EPU or Pt-GOD – were first immersed in PBS pH 7.4 and incubated at 37°C to ensure rapid swelling of enzyme and mass-transport limiting membranes and their function tested on 1, 3 and 7days. Following testing on day 7 the base sensors were rinsed in DI water and dried overnight in a fan assisted incubator at 37°C. The dried sensors were then coated with electrospun membranes to obtain coated sensor configurations Pt-GOD-EPU-ESC and Pt-GOD-ESC. The coated sensors were re-immersed in PBS pH 7.4 and incubated at 37°C and tested for sensor function on 1, 3 and 7days and thereafter weekly until 6weeks (42days) and biweekly until 12weeks (84days). Testing of control sensors (Pt-GOD-EPU and Pt-GOD) was done similarly, except that the base sensors were not coated with ESC membranes following the sensor drying step. Between the tests, the sensors were stored in PBS pH 7.4 at 37°C and the storage PBS refreshed every 2 to 5days. The change in sensitivity and linearity as a function of electrospun coating configuration and time was investigated. High variability in sensor sensitivity is observed both within and between the manually manufactured batches of the first generation glucose biosensors [15]. To distinguish the effects of electrospun coatings from sensor to sensor variability in sensitivity, the data at each time point for each individual sensor was normalised with its sensitivity on day 7 before applying the outermost test coating on the sensor and expressed as % change in sensitivity or linearity.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using statistical software (SPSS v.15). Statistical variances between groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey's test was used for post hoc evaluation of differences between groups. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 FEA simulations of electric-field distribution to identify optimum static collector system

Considering the disparity in size, shape and surface area available for deposition of fibres on the surface of a miniature biosensor compared to that of a flat-plate, it was first essential to identify the optimum collector configuration and distance from the spinneret for electrospinning fibres directly on biosensor surface. FEA modelling of electric-field distribution, similar to that reported earlier for obtaining desired patterned and 3D electrospun structures [29, 30], was used to identify the optimum static collector configuration.

For electrospinning PU on a flat-plate collector, an optimum distance of 22 cm between spinneret tip to collector was identified [26]. Hence for the initial FEA simulation, 22cm air gap was adapted. However, the flat-plate was replaced with the miniature coil-type glucose biosensor held perpendicular to the ground along the axis of the spinneret needle, using a 23G stainless needle such that the working collector (sensing element) along with about 5mm wire was exposed for deposition of electrospun fibre. Only the sensor wire was grounded.

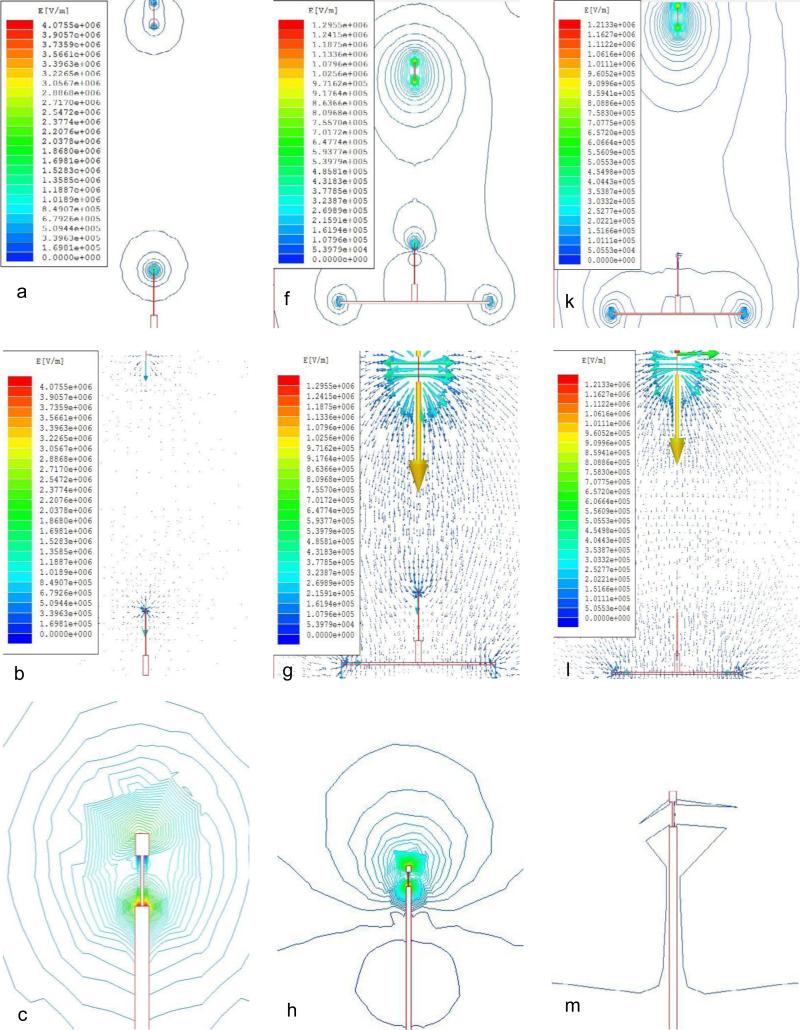

The FEA simulations, typically, showed that the concentration of electric-field around the electrodes (Fig 1a, f & k). The electric-field vector plots revealed electric-field vectors diverging from the spinneret tip and then converging at the collector (Fig 1b, g & l). Furthermore, the edges/ends of the spinneret, flat-plate, sensor and even the non-grounded conducting stainless steel holding needle caused focal points for higher electric-field strength (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

FEA simulation results showing electric-field (a-d, f-i, k-n) and potential (e, j, o) distributions between the spinneret and the collector systems – SCC-1 (a-e), SCC-2 (f-j) and SCC-3 (k-o). The legends represent increasing gradients of 25 colours indicating the increasing strength of electric-field (E (V/m)) or potential (Phi (V)) from blue to red. The length and thickness of the electric-field vector arrows also indicate the field strength. The collector system for SCC-1 (a-e) consisted of sensor and its holding needle alone with only the sensor grounded, and spinneret tip to sensor tip distance kept at 22 cm. For SCC-2 (f-j), sensor and its holding needle were fixed vertically in the centre of a grounded flat plat and spinneret tip to sensor tip distance was 16 cm. The SCC-3 (k-o) configuration was similar to that of SCC-2, but the spinneret tip to sensor tip distance was 22 cm.

In the SCC-1, where the sensor alone was used as the grounded collector, the electric-field strength (Fig 1a & c) at the sensor tip was stronger than that observed for SCC-2 (Fig 1f & h) and SCC-3 (Fig 1k & m). A nearly symmetric distribution of electric-field was observed at the sensor element for SCC-1 (Fig 1c). However, the electric-field around the sensing element was influenced by the tip (edge) of the non-grounded holding needle, where the electric-field strength distribution was the strongest (Fig 1c), which phenomenon was also reported earlier [31]. Furthermore, due to the small volume and area of the collecting sensor (<5mm diameter) compared to the large flat-plate (16 × 16 × 0.5mm), the electric-field focused at one point below the sensing element for SCC-1, where the electric-field vectors converged and then strongly reflected in all directions (Fig 1d), indicating that the uniform distribution for fibres on the sensor surface would be difficult to achieve.

To shift the focal point of electric-field from the collecting sensing element, the sensor along with its holding needle was integrated perpendicularly at the centre of a flat stainless steel plate. Both sensor, the main collector and flat-plate, the auxiliary collector were grounded. For this static collector system, referred to as SCC-2, the air gap between spinneret tip and flat-plate was 22cm, such that spinneret tip to sensing element distance was 16cm. SCC-2 induced an intense and laterally spread-out electric-field (Fig 1f & g) compared to SCC-1 and SCC-3. The edge effects were prominent, but the additional two focal points at the either ends of the flat-plate (Fig 1f) lowered the electric-field strength at the sensing element compared to that observed with SCC-1. However, the focus of the electric-field again was at the tip of the conducting stainless steel holding needle (Fig 1h & i), still resulting in the deflection of the electric-field vectors from the sensing element surface. Hence, the fibre deposition was expected to spread out from the tip of the sensing element to the flat-plate below forming a 3D umbrella shaped membrane, potentially not covering the entire sensing element surface.

For SCC-3, the air gap between spinneret tip to sensing element was increased to 22cm (the only difference from SCC-2) to significantly shifted the focus of the electric-field strength from the tip of the holding needle to the auxiliary electrode (flat-plate) (Fig 1k to n). Essentially, this resulted in the orientation of electric-field vectors predominantly downwards to the flat-plate along the axis of the sensor and its holding needle (Fig 1n), thus potentially ensuring a uniform distribution of electrospun fibres on the entire surface of the sensing element.

The spatial distribution of equi-potential lines between the electrodes (spinneret and collector systems), illustrated by the surface plots for SCC-1, SCC-2 and SCC-3 respectively in Fig 1e, j & o, further reiterates the observations for electric-field strength and direction shown in Fig 1a-d, f-h & k-n respectively. The focus of electrical potential gradually shifted from a single point at the tip of the sensor's holding needle in SCC-1 to the flat-plate auxiliary electrode in SCC-3 (Fig 1e, j & o), allowing a symmetric, uniform and well spread out electric potential and strength for SCC-3. An additional advantage for such uniform spatial distribution of electric potential was reported to aid formation of fibres of smaller diameters [32, 33]. Thus, the FEA simulations helped the identification of SCC-3 as the optimum static collector system for the actual electrospinning experiments.

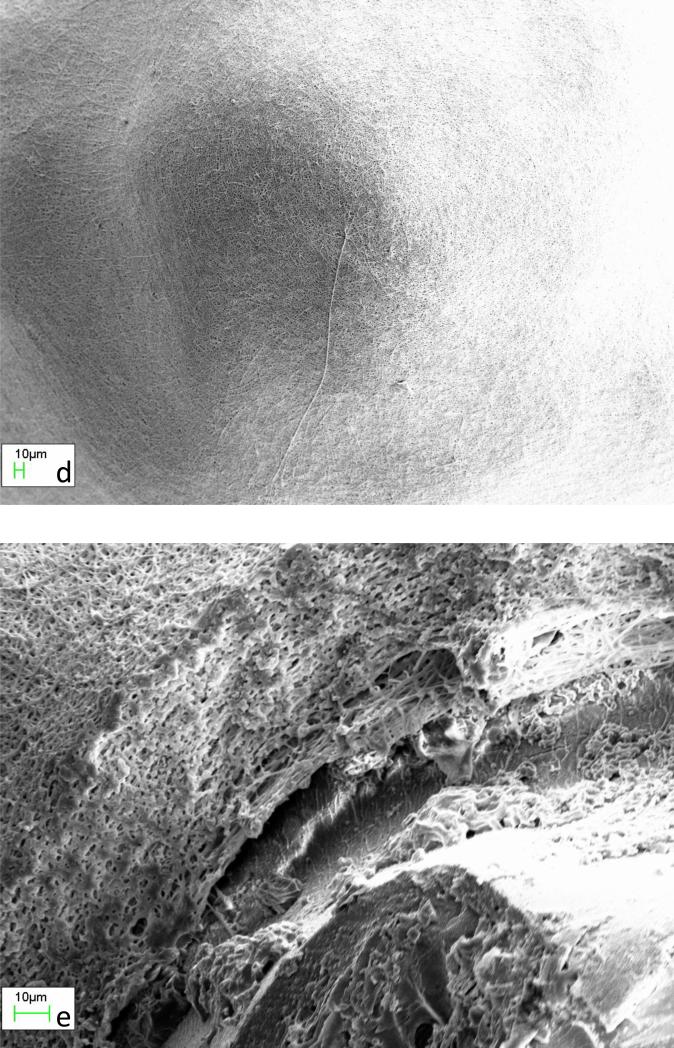

3.2 Morphology of PU coatings electrospun on sensor surface using static collector

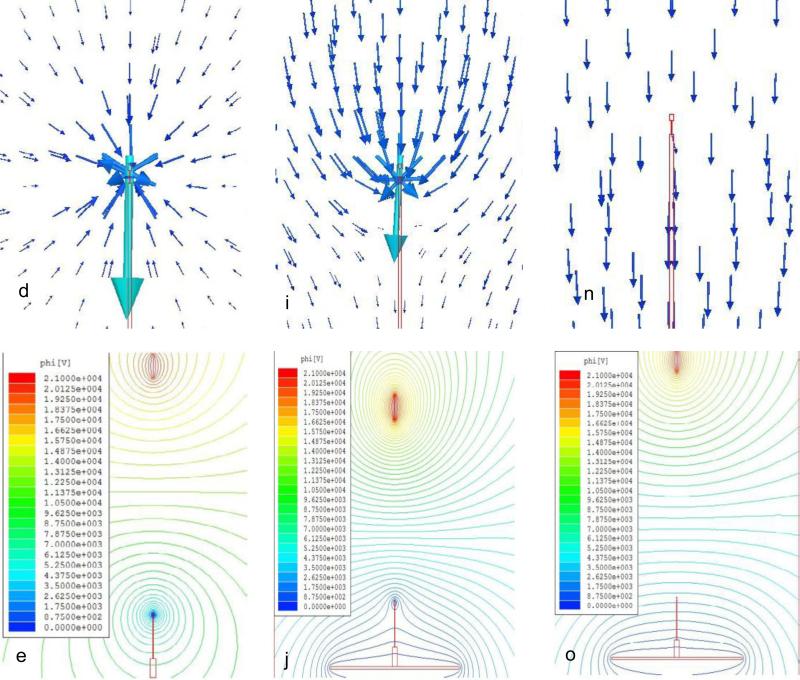

Fig 2a shows the morphology of electrospun 8PU-5’, 8PU-10’ and 8PU-30’ coatings on the miniature ellipsoid coil-type biosensor applied using SCC-3, with an applied voltage of 21kV. True to the FEA simulation the sensing element was completely covered by the electrospun fibres (Fig 2a). In fact, the coating was extended to about half the length on the holding needle (the boundary of the electric-field around the tip of the sensor holding needle closer to the flat-plate), from where, the fibrous membrane spread out in an umbrella shape. Thus, the objective of coating the entire surface of the sensing element was achieved. However, the coating was not uniform in thickness and 3D structure (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Optical microscopic images showing a) morphology as a function of electrospinning time, b) the cross-section on working electrode and c) the cross-section of the cut-off 8PU coating on the sensing element of the coil-type glucose biosensors, coated using static collector configuration-3. S – Sensing element, AP – Air Pockets.

The coating increased significantly in volume and thickness with increasing electrospinning time, and had ridge-grove structure on the lateral surface with interspersed spike-like structures having rounded ends and hollow core (Fig 2a to c). The ridges and grooves could be attributed to the distortion in electric-field around the sensing element due to the square shape of the flat-plate auxiliary electrode. Zhang et al reported that during the electrospinning process, fibres are driven by electrostatic forces to move towards the earthed substrate. But, as the fibres reach the collector surface, their deposition pattern would be determined by Coulombic interactions [34]. In addition, following deposition, any residual charge on the deposited fibres would also influence further deposition patterns for the fibres [35]. The accelerating polymer jet, when hits the tip of the stationary sensing element tip, could bend forming a loop such that, the entire length of polymer fibre doesn't contact the electrode surface. The looping of fibres could be responsible for the hollow spike-like structures (Fig 2b &c). Thus, the static nature of the collecting system coupled with the ellipsoid in the 3D space (compared to the conventional 2D flat-plate) and Coulombic interactions could be responsible for the unique 3D structure of the electrospun coating.

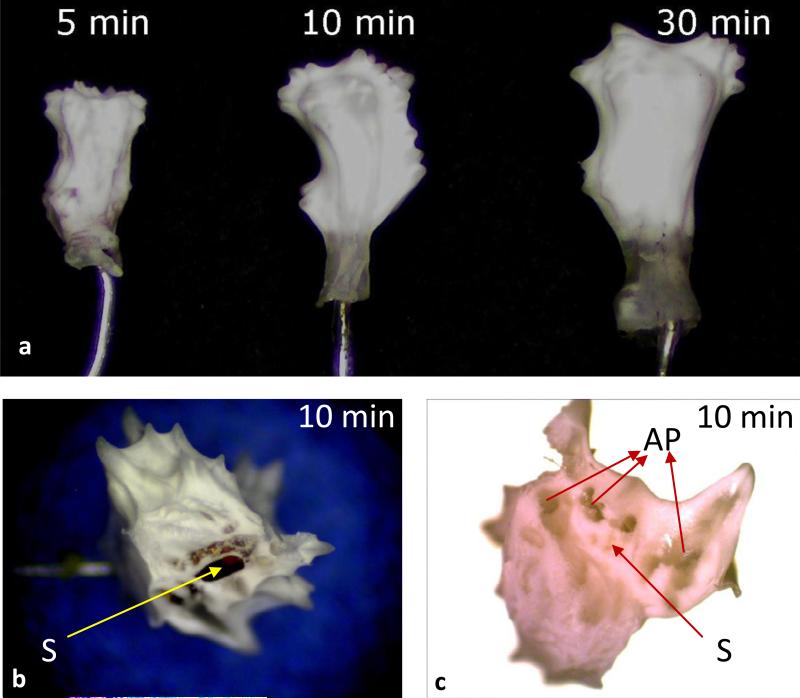

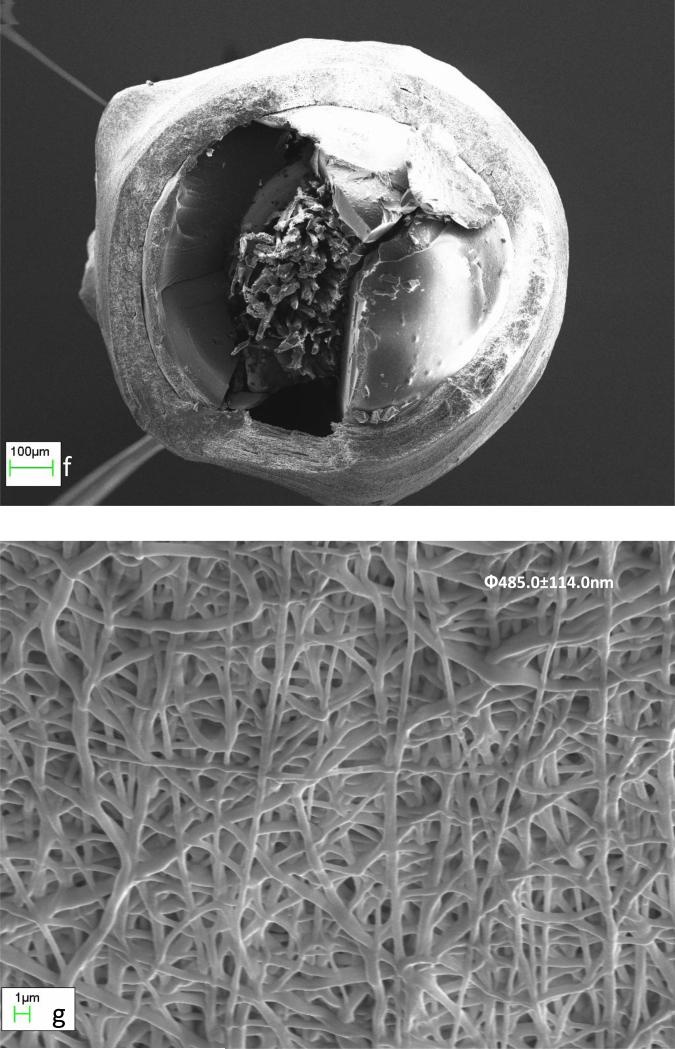

3.3 Morphology of PU coatings electrospun on sensor surface with dynamic collector

To overcome the limitation due to static nature of the tested collector configuration, the sensor was placed parallel to the auxiliary flat-plate collector and rotated at about 660 to 690rpm in the electrospinning field. The distance between the spinneret tip and the sensor surface was kept constant at 22cm. This resulted in the desired uniform coating of the sensor (Fig 3). The contour of the sensing element is clear after coating (Fig 3b&c) indicating a coating of uniform thickness. The coating was also uniform at the convex tip of the sensing element (Fig 3d), which could be due to the choice of rotating speed of the mandrel. The examination of cross-section of the membranes (Fig 3e&f) revealed uniform and interconnected porosity in the membrane. The rotation speed of 660-690rpm ensured the random orientation of the fibres (Fig 3g). The seamless fibre being generated by the electrospinning using similar rotation speeds, resulting in random fibre orientation, was also reported earlier [36]. Thus, the objective of snugly fit and uniform coating on the entire surface of the ellipsoid sensing element, having controllable fibre diameters and thickness was achieved.

Figure 3.

Optical microscope (a & b) and SEM (c) images showing the morphology of a coil-type biosensor without (a) and with (b to g) electrospun 8PU coating spun using a dynamic collector, showing the uniform covering of the miniature coil-type sensor including at its convex tip (d), while a closer look at its cross-section and surface revealed a uniform porosity (e & f) and random orientation of the electrospun fibres (g) respectively. Scale in a & b is in mm.

A comparison of the fibre diameters and thicknesses for PU membranes collected on flat-plate [26] and on sensors spun using static and dynamic collectors respectively is summarised in Table 3. In both cases, fibre diameters increased linearly with increasing PU feed solution concentration (8PU-5’, 10PU-5’ and 12PU-5’), but the slope for that on sensors decreased (y=99.597x-302.19, R2=0.9931, where x is PU feed solution concentration (%) and y is fibre diameter (nm)) compared to that on flat-plate (y=188.72x-1157.8, R2=9996). Thickness also increased linearly with increasing PU feed content for membranes electrospun on sensors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Fibre diameter and thickness differences for electrospun PU membranes spun on flat-plate collector (static collector) versus on sensors (dynamic collector) as a function of increasing feed PU solution concentration. Data expressed as mean ± SD, n=160.

| 8PU-5’ | 10PU-5’ | 12PU-5’ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Fibre Diameter (nm) | |||

| On Flat-plate | 347±88 | 738±131 | 1102±210 |

| On Sensor | 485±114 | 729±137 | 883±183 |

| Fibre Diameter Range (nm) | |||

| On Flat-plate | 175 to 738 | 465 to 1155 | 582 to 1706 |

| On Sensor | 260-690 | 386 to 1112 | 574 to 1331 |

| Thickness (μm) | |||

| On Flat-plate | 14.9±2.7 | 18.7±4.0 | 19.9±4.1 |

| On Sensor | 39.81±7.91 | 42.89±5.75 | 44.74±7.83 |

3.4 The basic coil-type glucose biosensor

The model implantable glucose biosensor, used in this study, is amperometric, enzymatic, and has a coil-type design standardized by Moussy's group [14-16, 37]. It is a two electrode system based on Pt-Ir coil working and Ag/AgCl coil reference electrodes. The coil design allows loading of excess enzyme to meet the demand for implantable application. Further, it uses an EPU membrane as the mass-transport limiting membrane, the crosslinking density and thickness of which can be varied to tune the sensitivity of the enzymatic sensor [16].

The primary objective for this study was to evaluate the effects of the electrospun coatings on sensor function in vitro. Since, additional coatings adversely affect sensor sensitivity, the design of the basic coil-type glucose biosensor reported by Yu et al. [16] was modified to maximize the base sensor sensitivity. The number of coatings (with ~2.5μl loading solution) for the enzyme layer was increased up to 4 layers. The thickened epoxy-PU seals (used by Yu et al. to lower the sensor sensitivity below 10nA/mM) at either ends of the working electrode were not applied. In addition, the thickness of mass-transport limiting EPU layer was also varied (1.5, 3, 6 and 12μl of EPU loading solutions) to identify a minimum coating volume for maximizing sensor sensitivity, while maintaining long-term sensor function. Since the volume of 12μl was too large to apply in one go, 6μl was applied first, allowed to air dry for 30min and then the second 6μl was applied before curing the EPU membrane. Sensors coated with single coats of EPU using 1.5, 3, or 6μl showed similar sensor sensitivities (normalised to that of each sensor before applying EPU membrane) (Table 4). But when two separate 6 μl coats were applied, there was significant decrease in sensitivity. All EPU coats improved the linearity (R2) for the detection range of 2 to 30mM from about 0.95 to 0.99 (Table 4). For studies evaluating the efficacy of electrospun coatings on sensor function, sensors having a single 1.5μl of EPU coating were used to ensure maximum base sensor sensitivity (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of solvent cast EPU membrane thickness on glucose biosensor function; Pt-GOD sensors were tested on 1, 3 and 7 days after immersing in PBS 7.4, then dried, EPU coats using 1.5, 3.0, 6.0 or 6.0 + 6.0 μl loading solution were applied, sensors re-immersed in PBS and tested on 1, 3 and 7 days. Sensitivity and linearity data is for that measured on day 7 after sensor coating, while the % sensitivity vs Pt-GOD is the % change of sensitivity for individual sensors (self-referenced) at 7th day testing after coating with EPU (Pt-GOD-EPU) compared to its sensitivity on 7th day test before applying the EPU coat (Pt-GOD). Data expressed as mean ± SD, n=6.

| Sensors | Sensitivity (nA/mM) | % Sensitivity Vs Pt-GOD | Linearity (R2 for 2 to 30 mM range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pt-GOD-EPU1.5 | 44.20 ± 4.06 | 82.61 ± 6.87 | 0.9898 ± 0.0038 |

| Pt-GOD-EPU3.0 | 40.09 ± 3.30 | 79.95 ± 6.68 | 0.9931 ± 0.0023 |

| Pt-GOD-EPU6.0 | 40.35 ± 2.30 | 78.83 ± 7.30 | 0.9938 ± 0.0013 |

| Pt-GOD-EPU6.0+6.0 | 12.03 ± 1.75 | 22.70 ± 3.49 | 0.9962 ± 0.0032 |

3.5 Effects of electrospun coatings on in vitro sensor sensitivity and linearity

The typical Pt-GOD-EPU sensors reported by Yu et al. show an increase in sensitivity up to 7 days of intermittent testing (similar to that reported in this study) and thereafter the sensitivity remains stable for the test period of 90 days [14]. The initial increase is attributed to initial sensor polarization combined with the swelling of enzyme and mass-transport-limiting membrane layers. As a result, for evaluating the effects of electrospun coatings, we adapted double testing to ensure comparison of stable sensitivities, wherein each sensor is tested before and after coating with electrospun membranes. The base Pt-GOD-EPU or Pt-GOD sensors, following their first-time immersion in PBS pH 7.4, were polarized at 0.7v and tested for sensitivity and linearity at 1, 3 and 7 days. The sensors are then washed, dried, coated with the test membranes, re-immersed in PBS 7.4 and tested again for sensitivity and linearity at 1, 3 and 7 days. The sensitivity and linearity of each of the sensors at 7th day testing after coating is self-referenced to that before coating.

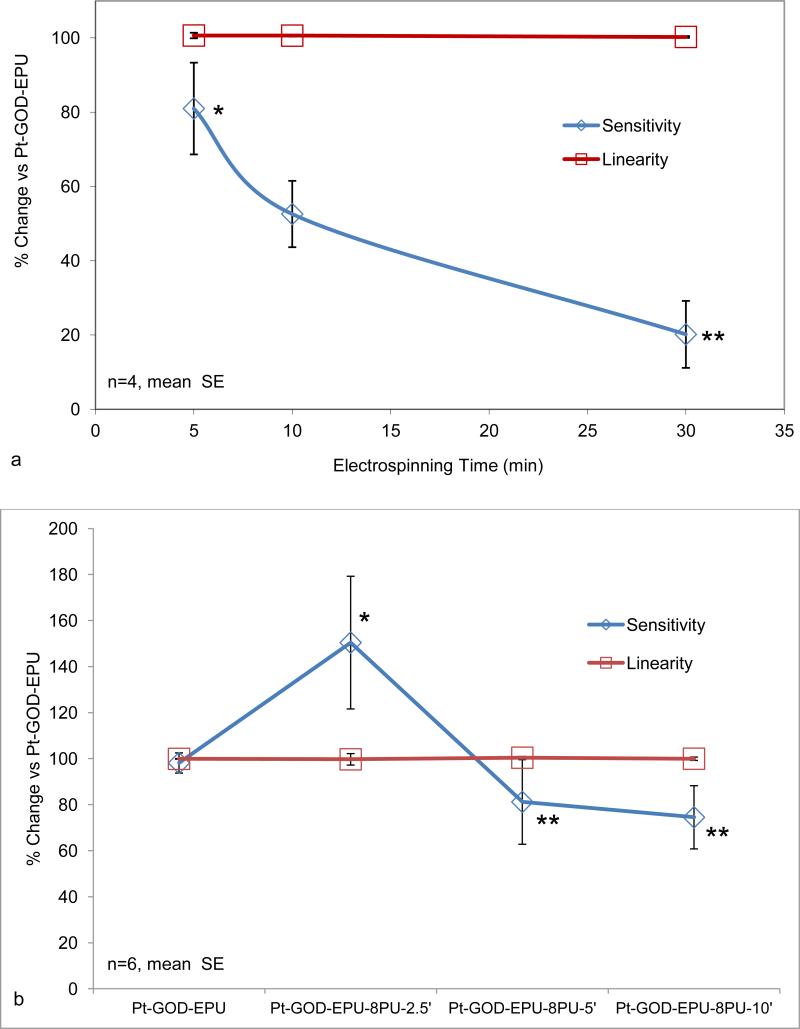

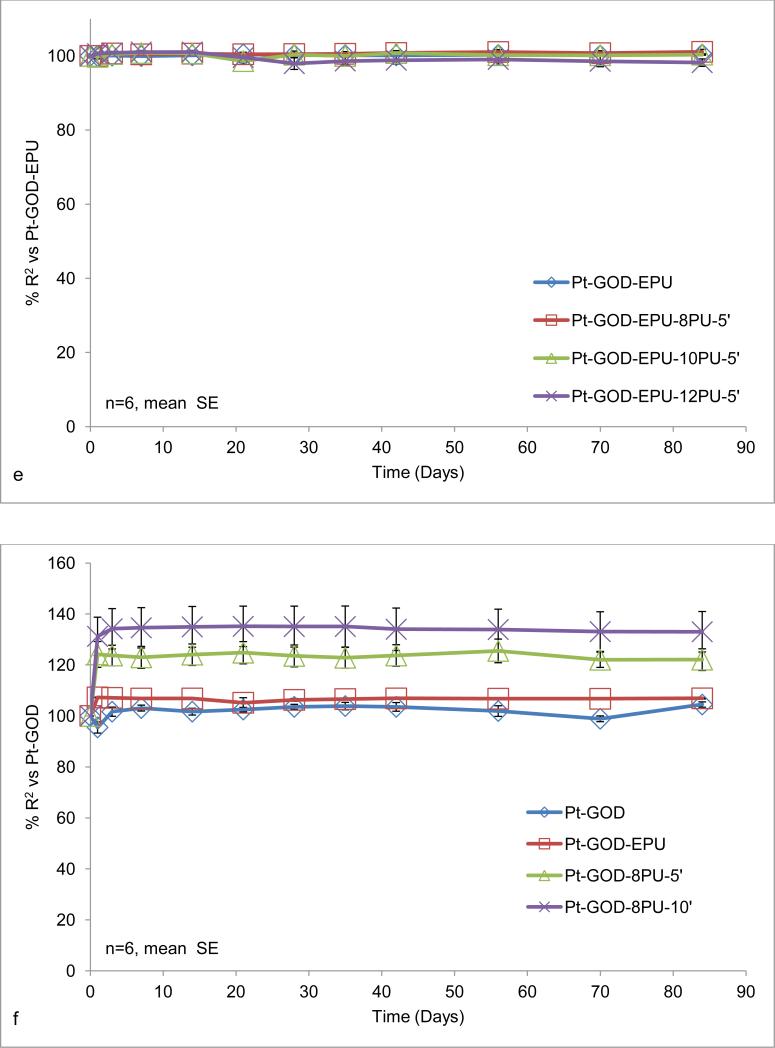

3.5.1 Pt-GOD-EPU sensors coated with 8PU membranes spun using static collection system

The sensitivity decreased with increasing volume of 8PU coating on the sensors, and the linearity remained unaffected (Fig 4a). The decrease in sensitivity was statistically different between 8PU-5’ and 8PU-30’ coats. The decrease of sensitivity with increasing thickness is as expected [38]. However, further studies using static collector system were abandoned because the uneven shape and thickness of the coatings (Fig 2) makes it difficult to ascertain a quantitative relationship between thickness and sensitivity.

Figure 4.

Effects of electrospun coatings on glucose-biosensor sensitivity and linearity: a) 8PU coatings (8PU-5’, 8PU-10’ or 8PU-30’) electrospun using static collector (SCC-3) on Pt-GOD-EPU base sensors as a function of increasing electrospinning time; b) 8PU coatings (8PU-2.5’, 8PU-5’ or 8PU-10’) electrospun using dynamic collector on Pt-GOD-EPU base sensors as a function of increasing membrane thickness; c) 8PU-5’, 10PU-5’ and 12PU-5’ coatings electrospun using dynamic collector on Pt-GOD-EPU base sensors as a function of increasing fibre diameter; and d) EPU, 8PU-5’, and 8PU-10’ coatings on Pt-GOD base sensors (electrospun coatings applied used dynamic collector) showing their efficacy as mass-transport limiting membranes. All sensors were tested for sensitivity and linearity before and after applying the different coatings (as described in section 3.5) and data represented as % change of sensitivity or linearity for the individual sensors of 7th day testing after coating self-referenced to that on 7th day test before coating. p<0.5 between * and **.

3.5.2 Pt-GOD-EPU sensors coated with 8PU membranes of increasing thickness spun using dynamic collection system

Anticipating about 20% decrease in sensor sensitivity as observed with the 8PU-5’ coating using the static collector (Fig 4a), the electrospinning times of 2.5, 5 and 10min were chosen to obtain membranes of varying thickness on sensors using the dynamic collector system. The resulting electrospun 8PU coatings had a linear increase in thickness (26.33±4.10, 39.81±7.91, 71.99±10.01μm, ±SD; R2 of 0.9984) with increasing electrospinning time (2.5, 5 and 10min respectively).

The sensitivity of sensors coated with 8PU-2.5’, 8PU-5’ and 8PU-10’, also decreased with increasing thickness. The decrease in sensitivity between Pt-GOD-EPU-8PU-5’ and Pt-GOD-EPU-8PU-10’ sensors was statistically insignificant for the n=6 sensors per test membrane configuration (Fig 4b). However, Pt-GOD-EPU-8PU-2.5’ sensors showed sensitivity significantly higher than all the other test sensors including the control (Fig 4b). This was un-expected and could be due to the permeability kinetics of the thin fibro-porous 8PU membrane on the immediate surface of EPU mass-transport limiting membrane. A maximum decrease of about 25% in sensitivity was observed for Pt-GOD-EPU-8PU-10’ having a coating thickness of 72μm. However, no change in linearity for the 2 to 30mM glucose detection range was observed for any of the sensors (Fig 4b).

3.5.3 Pt-GOD-EPU sensors coated with electrospun PU membranes of increasing fibre diameters spun using dynamic collection system

Our previous study showed that increasing average fibre diameter (347, 738 and 1102 nm) for 8PU, 10PU and 12PU membranes spun on static flat-plate resulted in an increase in pore size (800, 870 and 1060nm) and pore volume (44, 63 and 68%)) [26]. Hence, the increasing fibre diameters (485, 729 and 883 nm) for the 8PU, 10PU and 12PU membranes spun on Pt-GOD-EPU sensors were also considered to have increasing porosity and thickness, the effects of which on sensor response sensitivity and linearity are illustrated in Fig 4c. The increase in fibre diameters resulted in a linear but statistically insignificant decrease in sensor sensitivity (n=6), while the sensors’ linearity was not affected. A maximum decrease in sensitivity of about 29% was observed for Pt-GOD-EPU-12PU-5’.

3.5.4 Pt-GOD sensors coated with EPU, 8PU-5’ and 8PU-10’ as mass-transport limiting membranes

Considering their submicron and highly interconnected porosity, 8PU membranes were also anticipated to function as mass-transport limiting membranes for glucose biosensors. 8PU membranes were spun directly on Pt-GOD sensors to test their ability to function as mass-transport limiting membranes and the sensitivity and linearity of the resulting sensors are illustrated in Fig 4d. Statistical increase in the sensitivity and linearity (R2) were observed for membranes 8PU-5’ and 8PU-10’, compared to Pt-GOD base sensors. The results indicate that electrospun 8PU-5’ and 8PU-10’ membranes have performance similar to traditional EPU and can function as mass-transport limiting membranes.

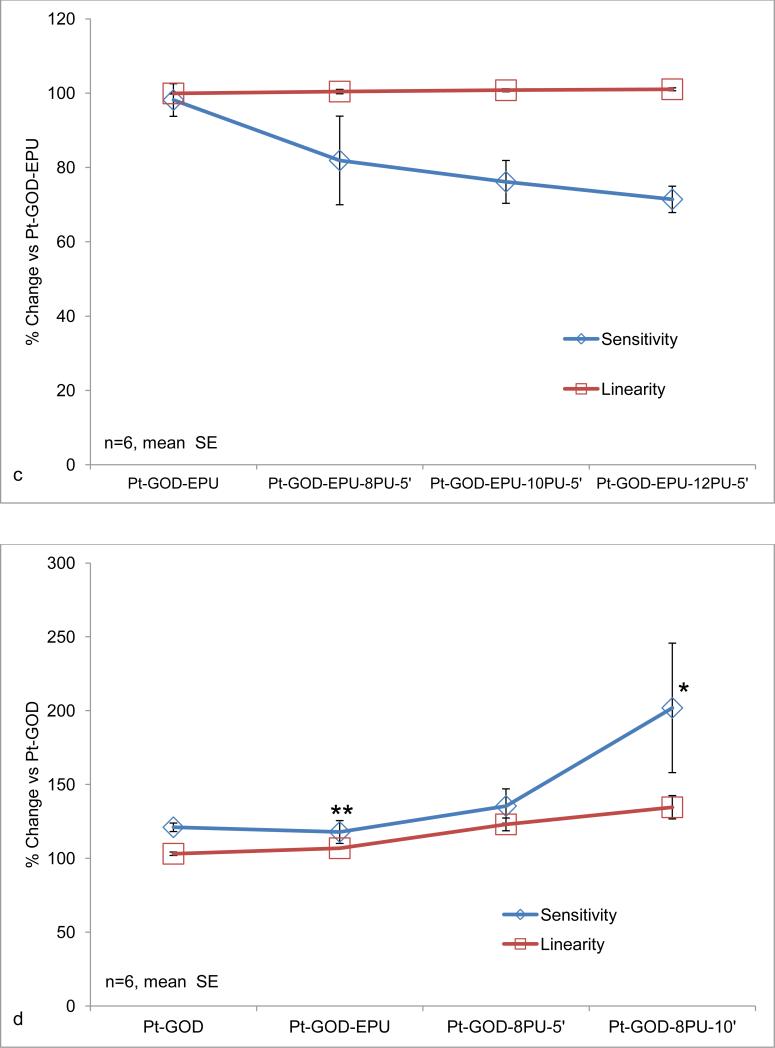

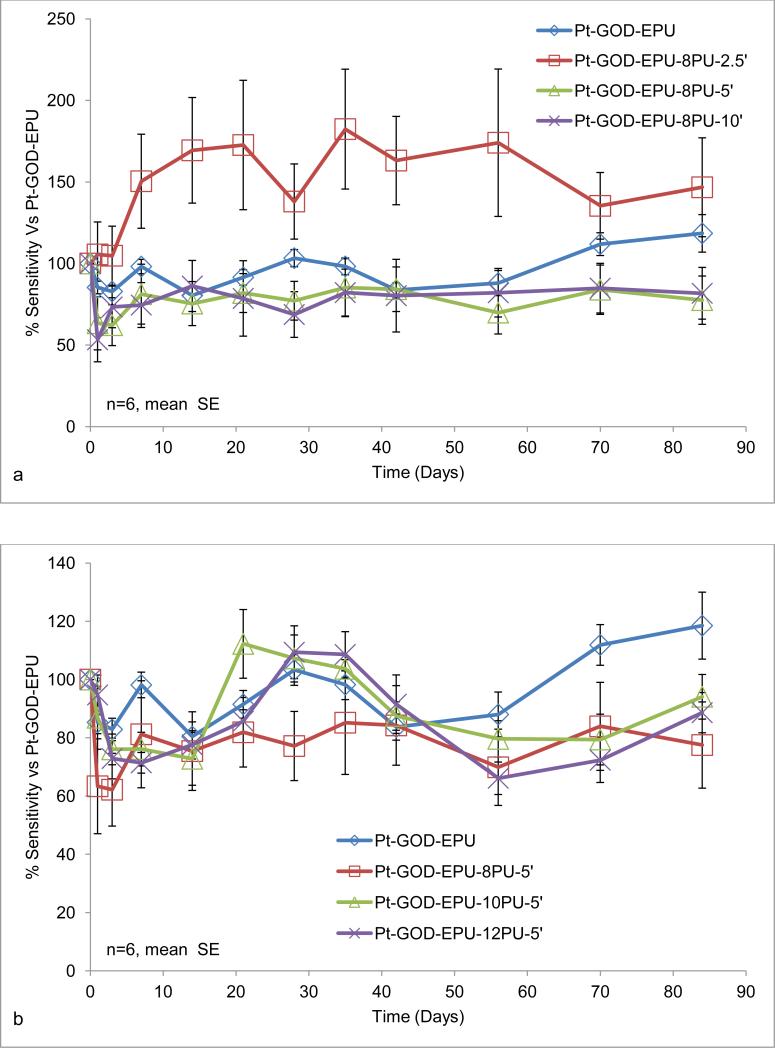

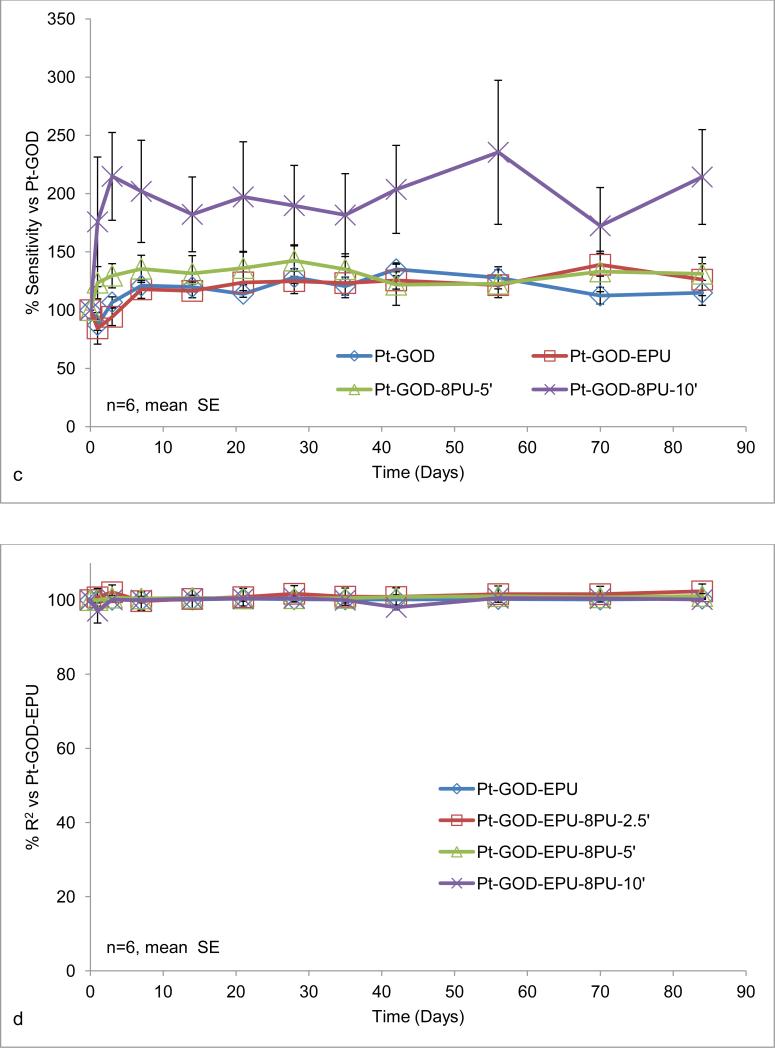

3.6 Long-term stability of sensor function for glucose biosensors before and after coating with electrospun membranes

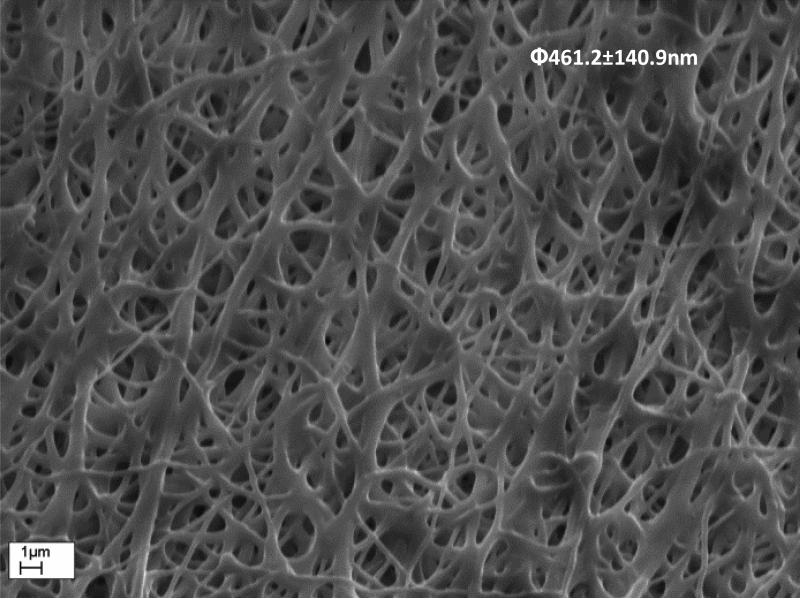

Long-term effect of the electrospun membranes on sensor function was assessed by intermittent testing up to 84 days. The different membranes tested on both Pt-GOD-EPU and Pt-GOD base sensors did not cause any statistically significant changes in sensor response sensitivity and linearity for 84days of testing (Fig 5a-f). It must be emphasised that when electrospun membranes, 8PU-5’ and 8PU-10’, were used as mass-transport limiting membranes replacing traditional EPU outer layer, they not only extended the linear glucose detection range to cover the desired 2 to 30mM, but also maintained the stable sensor sensitivity till 84days of testing (Fig 5c and f). Morphology assessments using SEM (Fig 6) showed that the average PU fibre diameters decreased by about 5% (485±114 to 461±141nm, 729±137 to 688±150nm, and 883±183 to 831±163nm respectively for 8PU-5’, 10PU-5’ and 12PU-5’ respectively on Pt-GOD-EPU base sensors) under continuous incubation at 37°C, with intermittent sensor function tests. The slight decrease in fibre diameter can be attributed to the slow degradation of PU fibre through surface erosion similar to that reported earlier [39]. However, as the long-term sensor performance results indicated that the slight decrease in fibre diameter did not have any apparent effect on sensor function for the test period of 84days.

Figure 5.

Long-term changes in sensor response sensitivity (a-c) and linearity (d-f) based on intermittent sensor function tests: a & d) 8PU coatings (8PU-2.5’, 8PU-5’ or 8PU-10’) electrospun using dynamic collector on Pt-GOD-EPU base sensors, as a function of increasing membrane thickness; b & e) 8PU-5’, 10PU-5’ and 12PU-5’ coatings electrospun using dynamic collector on Pt-GOD-EPU base sensors, as a function of increasing fibre diameter; and c & f) EPU, 8PU-5’, and 8PU-10’ coatings on Pt-GOD base sensors (electrospun coatings applied used dynamic collector) showing their efficacy as mass-transport limiting membranes. All sensors were tested for sensitivity and linearity before and after applying the different coatings (as described in section 3.5) and data represented as % change of sensitivity or linearity for the individual sensors of 7th day testing after coating self-referenced to that on 7th day test before coating.

Figure 6.

SEM image showing surface morphology on 8PU-5’ electrospun membrane on sensor after long-term (84days) in vitro sensor functional efficacy testing.

4 Discussion

Electrospinning is a well-established science, and a significant volume of research has gone in the process optimization for a variety of polymers. In our research, we apply the technology to coat implantable biosensors with the ultimate goal of improving their performance and longevity when implanted in the body. Electrospinning has been extensively used to generate polymer fibres having large surface to volume ratios, excellent physical and chemical properties and fibro-porous structure mimicking the natural extracellular matrix (ECM) to suit a variety of applications including drug delivery, tissue engineering and biosensing [40-43]. However, in most of these studies, electrospun fibres were collected as two dimensional membranes on flat electrodes and rotating drums or tubes. In the present study, the main challenge was assembling of a uniform coating of fibres on miniature 3D ellipsoid shaped sensing element. The coatings should have uniform thickness, completely cover and fit snugly on the sensor surface, while having random fibre orientation (for mechanical integrity) and large pore volumes (for maximum permeability to analyte).

The assembly of electrospun fibres in the form of macroscopic 3D tubular structures is commonly done by using a rotating collector [44, 45]. Furthermore, the alignment of fibres can be controlled by varying the rotation speed of the collecting mandrel and thus tailor the material properties of engineered membrane/matrix [46, 47]. Nevertheless, this method has limitations, especially in the fabrication of tiny tubes of less than 0.3 mm diameter having one end closed, and tubes with multiple interconnected tubes [36]. Zhang et al utilized novel static methods in the electrospinning setup to overcome these limitations. They used multiple collecting elements (assistant collectors together with working collectors) to alter the electric-field to generate the desired tubular electrospun structures [34]. To identify the optimum collecting system for spinning polymer fibres directly on miniature sensors, in this study, two collecting systems (static and dynamic) were designed and FEA simulation of electric-field distributions (Fig 1) used to identify optimum conditions for electrospinning directly on sensor surface. In either case, the sensor was grounded and when used the grounded flat-plate was the auxiliary collecting electrode. Both static and dynamic collection systems allowed complete covering of the ellipsoid sensors. However, the coatings applied using static collector system were irregular, having ridges and groves as well as hollow spikes (Fig 2), which structure can be attributed to the irregular 3D electric-field distribution caused by the square-plate auxiliary electrode. Further studies, with static collector systems was abandoned since our objective of applying uniform coating on the entire ellipsoid sensing element including its rounded tip was achieved using a dynamic collector system (Fig 3), which can be attributed to the whipping electrospinning jet combined with optimum rotation speed for sensor in the field of electrospinning. Additional studies with modified static collector system, wherein the square-plate auxiliary collector is replaced with a round-plate to generate uniform 3D electric-field distribution could be of academic interest.

Further objective for this study was to evaluate the effects of electrospun coatings on sensor function. Coil-type amperometric implantable glucose biosensors reported by Yu et al. were used as the model sensors [14]. The first generation glucose biosensor was chosen, since such sensors are still the gold standard for commercial implantable CGM devices [48, 49] and the use of second generation glucose biosensors is generally avoided because of susceptibility to leaching of their component artificial redox mediators that are lethal for host tissue and organ systems. It is essential to highlight that the first generation glucose biosensor is an enzymatic sensor, wherein the enzyme GOD is susceptible to degradation or inactivation, which can further be accelerated by the accumulation of H2O2 accumulated in the enzyme layer during inherent delays between measurements [14, 50]. This inherent limitation of sensitivity drift was minimized by Yu et al., through cotton-reinforced coil electrode loaded with excess enzyme [14]. It was not our objective to further address this limitation. However, to minimize the interference of the sensitivity drift with our study of efficacy of electrospun coatings on sensor function, we modified the long-term sensor function assessment method from that reported by Yu et al. [14]. Between the intermittent sensitivity tests, the sensors were stored in PBS pH 7.4 at 37°C instead of 5mM glucose solution in PBS at room temperature. This prevents accumulation of H2O2 in the enzyme layer responsible for sensor drift. Storing at 37°C also allows faster stabilization of sensor response sensitivity through faster swelling of the enzyme and other coating layers on the electrode.

The effects of ESC on sensor function were tested as a function of increasing thickness and fibre diameters. In general, increasing thickness caused decrease in sensor sensitivity as can be expected (Fig 4a-c). The decrease was usually statistically insignificant for both ESC and EPU, when the coating was applied in a single step. However, when EPU was applied as two separate coats, the sensitivity reduced drastically, which reiterated that the surface to surface interconnectivity of the pore network is essential for higher flux of trans-membrane analyte transport [51]. Thus, any decrease in sensitivity can be attributed to the increasing trans-membrane distance the analyte needs to diffuse through, which is clear from the decrease in diffusion coefficients with increasing thickness of electrospun membranes spun on flat-plate collector (Table 1) [26]. Assuming, excellent interconnectivity of pore network, sensitivity of sensors can be modulated by varying the sensor coating thickness. ESCs provide both excellent interconnectivity and desired thickness, which is relatively difficult to achieve using traditional solvent-cast coatings.

Repeated testing of sensor function showed that sensitivity typically increased up to 7 days and then remained stable (no statistical change) for the rest of the study period of 84days (Fig 5). Thus, the new testing regime and modifications to working electrode composition still showed similar results for the base sensor configuration as reported by Yu et al. [14]. Sensors coated with all test electrospun membrane configurations also showed similar result indicating the long-term stability of the membranes. At the end of 84day study period, SEM morphology confirmed the structural integrity of the ESC, an example illustrated in (Fig 6). Measurements of fibre diameters ESC revealed that there was about 5% decrease in fibre diameters owing to surface erosion. However, this decrease did not appear to effect sensor function (Fig 5).

There were discrepancies in the trends for changes in sensitivities when the Pt-GOD base sensors were tested without mass-transport limiting membranes (Table 4, Fig 4d, Fig 5c &f). The pre-coating tests on 1, 3 and 7 days, showed decreasing sensor response linearity from day 1 to 7, indicating faster saturation of the enzyme due to increasing swelling and lack of mass-transport limiting membrane. The drying and re-testing of Pt-GOD sensors showed about 20% increase in sensitivity and also a slight increase in linearity, both of which are maintained for the rest of the study period (Fig 4d, Fig 5c & f). This indicates some sort of reorganization of the enzyme layer potentially due to the susceptibility of the Schiff's base crosslinks of glutaraldehyde to H2O2 and de-hydro-thermal crosslinking during the drying cycle. The resulting change in the baseline sensitivity for Pt-GOD sensors from before and after coating makes it difficult to deduce numerical trends for effects of EPU or ESC coatings. However, the ESC and EPU coatings significantly increased the sensor response linearity covering the desired 2 to 30 mM glucose detection range and the performance of ESC was to traditional EPU membrane, indicating that ESC can function as mass-transport limiting membranes.

It is well known that first generation implantable glucose biosensors are susceptible to factors including sensitivity drift, interference from other electroactive agents in complex biological media, O2 dependence and failure upon implantation in the body that effect the long-term performance of the biosensors [1, 17, 48, 49, 52]. Key strategies to overcome these limitations often require multiple layers of coatings, e.g., interference eliminating layer(s), mass-transport limiting layer and host response engineering layer(s) (for biocompatibility). The results of this study indicate that each individual layer of coating can significantly increase the analyte flow resistance, thus lowering the pre-implantation sensitivity of the sensor. On the other hand, the electrospun coating can potentially provide those desired multifunction in one process so as to minimise the number of coating layers and reduction of the sensor sensitivity. The higher the sensor sensitivity, the better the signal to noise ratio and hence the better will be the sensor performance. As a result, maximising pre-implantation sensor sensitivity for the base sensor can be of strategic importance for the final sensor design requiring additional coatings.

5 Conclusions

The objective of electrospinning snugly fit membranes covering the entire surface of miniature ellipsoid glucose biosensors was achieved using both static and dynamic collection systems. However, the membrane was uniform in thickness, including at the rounded end of the working electrode, only for that spun using dynamic collection system. There slope for increase in fibre diameters with increasing feed PU solution concentration for membranes spun directly on sensor surface using dynamic collection system decreased compared those spun on a static flat-plate. The membrane thickness increased linearly with increasing electrospinning time. On sensors, the ESCs caused a 20 to 30% decrease in sensitivity for thicknesses ranging from 25 to 72μm. They also functioned as mass transport limiting membranes, achieving R2 of about 0.99 for glucose detection range of 2 to 30mM. The integrity of the ESCs and resulting sensor response sensitivities were maintained for the study period of 84days. Key advantages for electrospun membranes over tradition solvent cast membranes is that the well-controlled interconnecting porous structure, thickness and permeability of the coating can be achieved in a single electrospinnig setup, and they can withstand larger pressures exerted by the swelling of the inner enzyme ± mass-transport limiting layers. Overall, this study demonstrated that electrospinning can be used to coat miniature biosensors with fibro-porous membranes of desired properties, which is difficult to achieve with traditional solvent cast membranes. Single or multiple electrospun layers can be used to address mass-transport limiting and additional membranes for improving biocompatibility of implantable biosensors and other biomedical devices requiring analyte transport, especially the first generation implantable glucose biosensors. Future reports would include pre-clinical functional efficacy studies.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Brunel University, the Royal Society research grant (RG100129), the Royal Society-NSFC international joint project grant (JP101064) and the National Institute of Health (NIH/NIBIB, grant R01EB001640).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wisniewski N, Reichert M. Methods for reducing biosensor membrane biofouling. Colloid Surface B. 2000;18:197–219. doi: 10.1016/s0927-7765(99)00148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharkawy AA, Klitzman B, Truskey GA, Reichert WM. Engineering the tissue which encapsulates subcutaneous implants. I. Diffusion properties. J Biomed Mater Res A. 1997;37:401–12. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19971205)37:3<401::aid-jbm11>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koschwanez HE, Yap FY, Klitzman B, Reichert WM. In vitro and in vivo characterization of porous poly-l-lactic acid coatings for subcutaneously implanted glucose sensors. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;87:792–807. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brauker JH, Carr-Brendel V, Tapsak MA. Porous membranes for use with implantable devices. 2012 US Patent: 8118877.

- 5.Ding B, Wang M, Wang X, Yu J, Sun G. Electrospun nanomaterials for ultrasensitive sensors. Mater Today. 2010;13:16–27. doi: 10.1016/S1369-7021(10)70200-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abidian MR, Martin DC. Multifunctional nanobiomaterials for neural interfaces. Adv Funct Mater. 2009;19:573–85. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsumoto T, Furusawa M, Fujiwara H, Matsumoto Y, Ito N. A micro-planar amperometric glucose sensor unsusceptible to interference species. Sensor Actuat B-Chem. 1998;49:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward WK, Jansen LB, Anderson E, Reach G, Klein J-C, Wilson GS. A new amperometric glucose microsensor: In vitro and short-term in vivo evaluation. Biosens Bioelectron. 2002;17:181–9. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(01)00268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linke B, Kerner W, Kiwit M, Pishko M, Heller A. Amperometric biosensor for in vivo glucose sensing based on glucose oxidase immobilized in a redox hydrogel. Biosens Bioelectron. 1994;9:151–8. doi: 10.1016/0956-5663(94)80107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy SM, Vadgama P. Entrapment of glucose oxidase in non-porous poly(vinyl chloride). Anal Chim Acta. 2002;461:57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung TD. In vitro evaluation of the continuous monitoring glucose sensors with perfluorinated tetrafluoroethylene coatings. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2002;24:514–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moussy F, Harrison DJ, Rajotte RV. A miniaturized nafion-based glucose sensor: In vitro and in vivo evaluation in dogs. Int J Artif Organs. 1994;17:88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madaras MB, Popescu IC, Ufer S, Buck RP. Microfabricated amperometric creatine and creatinine biosensors. Anal Chim Acta. 1996;319:335–45. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu B, Moussy Y, Moussy F. Coil-type implantable glucose biosensor with excess enzyme loading. Front Biosci. 2005;10:512–20. doi: 10.2741/1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trzebinski J, Moniz AR-B, Sharma S, Burugapalli K, Moussy F, Cass AEG. Hydrogel membrane improves batch-to-batch reproducibility of an enzymatic glucose biosensor. Electroanalysis. 2011;23:2789–95. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu B, Long N, Moussy Y, Moussy F. A long-term flexible minimally-invasive implantable glucose biosensor based on an epoxy-enhanced polyurethane membrane. Biosens Bioelectron. 2006;21:2275–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wisniewski N, Moussy F, Reichert WM. Characterization of implantable biosensor membrane biofouling. Fresenius J Anal Chem. 2000;366:611–21. doi: 10.1007/s002160051556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaddiraju S, Tomazos I, Burgess DJ, Jain FC, Papadimitrakopoulos F. Emerging synergy between nanotechnology and implantable biosensors: A review. Biosens Bioelectron. 2010;25:1553–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y, Zhang SF, Kingston MA, Jones G, Wright G, Spencer SA. Glucose sensor with improved haemocompatibilty. Biosens Bioelectron. 2000;15:221–7. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(00)00082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishihara K, Nakabayashi N, Nishida K, Sakakida M, Shichiri M. New biocompatible polymer. Diagnostic biosensor polymers: ACS Symp Ser. 1994;556:194–210. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishihara K, Tanaka S, Furukawa N, Nakabayashi N, Kurita K. Improved blood compatibility of segmented polyurethanes by polymeric additives having phospholipid polar groups. I. Molecular design of polymeric additives and their functions. J Biomed Mater Res A. 1996;32:391–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199611)32:3<391::AID-JBM12>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galeska I, Hickey T, Moussy F, Kreutzer D, Papadimitrakopoulos F. Characterization and biocompatibility studies of novel humic acids based films as membrane material for an implantable glucose sensor. Biomacromolecules. 2001;2:1249–55. doi: 10.1021/bm010112y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Praveen SS, Hanumantha R, Belovich JM, Davis BL. Novel hyaluronic acid coating for potential use in glucose sensor design. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2003;5:393–9. doi: 10.1089/152091503765691893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onuki Y, Bhardwaj U, Papadimitrakopoulos F, Burgess DJ. A review of the biocompatibility of implantable devices: Current challenges to overcome foreign body response. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2:1003–15. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishnan S, Weinman CJ, Ober CK. Advances in polymers for anti-biofouling surfaces. J Mater Chem. 2008;18:3405–13. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang N, Burugapalli K, Song W, Halls J, Moussy F, Zheng Y, et al. Tailored fibro-porous structure of electrospun polyurethane membranes, their size-dependent properties and trans-membrane glucose diffusion. J Membr Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2012.09.052. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Os PJHJ, Bult A, Van Bennekom WP. A glucose sensor, interference free for ascorbic acid. Anal Chim Acta. 1995;305:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uang Y-M, Chou T-C. Fabrication of glucose oxidase/polypyrrole biosensor by galvanostatic method in various ph aqueous solutions. Biosens Bioelectron. 2003;19:141–7. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(03)00168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Theron A, Zussman E, Yarin AL. Electrostatic field-assisted alignment of electrospun nanofibres. Nanotechnology. 2001;12:384–90. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deitzel JM, Kleinmeyer JD, Hirvonen JK, Beck Tan NC. Controlled deposition of electrospun poly(ethylene oxide) fibers. Polymer. 2001;42:8163–70. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang D, Chang J. Electrospinning of three-dimensional nanofibrous tubes with controllable architectures. Nano Lett. 2008;8:3283–7. doi: 10.1021/nl801667s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Y, Jia Z, Liu J, Li Q, Hou L, Wang L, et al. Effect of electric field distribution uniformity on electrospinning. J Appl Phys. 2008;103:104307–11. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kong C, Lee T, Lee S, Kim H. Nano-web formation by the electrospinning at various electric fields. J Mater Sci. 2007;42:8106–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang D, Chang J. Patterning of electrospun fibers using electroconductive templates. Adv Mater. 2007;19:3664–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deitzel JM, Kleinmeyer J, Harris D, Beck Tan NC. The effect of processing variables on the morphology of electrospun nanofibers and textiles. Polymer. 2001;42:261–72. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teo WE, Ramakrishna S. A review on electrospinning design and nanofibre assemblies. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:R89. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/17/14/R01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu B, Ju Y, West L, Moussy Y, Moussy F. An investigation of long-term performance of minimally invasive glucose biosensors. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2007;9:265–75. doi: 10.1089/dia.2006.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu B, Wang C, Ju YM, West L, Harmon J, Moussy Y, et al. Use of hydrogel coating to improve the performance of implanted glucose sensors. Biosens Bioelectron. 2008;23:1278–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henry JA, Simonet M, Pandit A, Neuenschwander P. Characterization of a slowly degrading biodegradable polyesterurethane for tissue engineering scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;82:669–79. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang ZG, Wano Y, Xu H, Li G, Xu ZK. Carbon nanotube-filled nanofibrous membranes electrospun from poly(acrylonitrile-co-acrylic acid) for glucose biosensor. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:2955–60. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren G, Xu X, Liu Q, Cheng J, Yuan X, Wu L, et al. Electrospun poly(vinyl alcohol)/glucose oxidase biocomposite membranes for biosensor applications. React Funct Polym. 2006;66:1559–64. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manesh KM, Kim HT, Santhosh P, Gopalan AI, Lee K-P. A novel glucose biosensor based on immobilization of glucose oxidase into multiwall carbon nanotubes polyelectrolyte-loaded electrospun nanofibrous membrane. Biosens Bioelectron. 2008;23:771–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shults MC, Updike SJ, Rhodes RK, Gilligan BJ, Tapsak MA. Device and method for determining analyte levels. 2010 US Patent.

- 44.Stitzel J, Liu J, Lee SJ, Komura M, Berry J, Soker S, et al. Controlled fabrication of a biological vascular substitute. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1088–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuda T, Ihara M, Inoguchi H, Kwon IK, Takamizawa K, Kidoaki S. Mechanoactive scaffold design of small-diameter artificial graft made of electrospun segmented polyurethane fabrics. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;73:125–31. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matthews JA, Wnek GE, Simpson DG, Bowlin GL. Electrospinning of collagen nanofibers. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:232–8. doi: 10.1021/bm015533u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim K, Lee K, Khil M, Ho Y, Kim H. The effect of molecular weight and the linear velocity of drum surface on the properties of electrospun poly(ethylene terephthalate) nonwovens. Fibers Polym. 2004;5:122–7. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heller A, Feldman B. Electrochemical glucose sensors and their applications in diabetes management. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2482–505. doi: 10.1021/cr068069y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang J. Electrochemical glucose biosensors. Chem Rev. 2008;108:814–25. doi: 10.1021/cr068123a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valdes TI, Moussy F. In vitro and in vivo degradation of glucose oxidase enzyme used for an implantable glucose biosensor. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2000;2:367–76. doi: 10.1089/15209150050194233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gilda S, Nelson F, Youngjin C, Margarita C, Michael LS, Christopher KO, et al. Synthesis and characterization of high-throughput nanofabricated poly(4-hydroxy styrene) membranes for in vitro models of barrier tissue. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2012;18:667–76. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2011.0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wisniewski N, Klitzman B, Miller B, Reichert WM. Decreased analyte transport through implanted membranes: Differentiation of biofouling from tissue effects. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2001;57:513–21. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20011215)57:4<513::aid-jbm1197>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]