Abstract

Tripartite motif-containing 21 (TRIM21) is a cytosolic IgG receptor that mediates intracellular virus neutralization by antibody. TRIM21 targets virions for destruction in the proteasome, but it is unclear how a substrate as large as a viral capsid is degraded. Here, we identify the ATPase p97/valosin-containing protein (VCP), an enzyme with segregase and unfoldase activity, as a key player in this process. Depletion or catalytic inhibition of VCP prevents capsid degradation and reduces neutralization. VCP is required concurrently with the proteasome, as addition of inhibitor after proteasomal degradation has no effect. Moreover, our results suggest that it is the challenging nature of virus as a substrate that necessitates involvement of VCP, since intracellularly expressed IgG Fc is degraded in a VCP-independent manner. These results implicate VCP as an important host factor in antiviral immunity.

Keywords: intracellular immunity, Cdc48

Antibody neutralization is a key component of the antiviral response and provides protective immunity. Our recent work has shown that neutralization can occur inside cells, in an effector-driven process mediated by tripartite motif-containing 21 (TRIM21). TRIM21, a cytosolic antibody receptor of ultrahigh affinity to IgG Fc (1, 2), is recruited to antibody-bound virus and targets the complex to the proteasome for degradation (3). This process potently neutralizes viral infection and has been termed antibody-dependent intracellular neutralization (ADIN) (4). ADIN is dependent upon the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of TRIM21 and can be abrogated by chemical inhibition of the proteasome.

Although both proteasomal activity and ubiquitination are necessary for ADIN, the exact mechanism of virus degradation is poorly understood. Specifically, it is not clear how the proteasome can degrade a virion, a compact proteinaceous particle much larger than the proteasome itself. The 26S proteasome has a mass of ∼2.5 MDa (5), and the pore through which substrates must pass to access the proteolytic chamber is no greater than 2 nm in diameter (6, 7). In contrast, human adenovirus (AdV), a virus potently neutralized by TRIM21, has a diameter of ∼100 nm and a mass of 150 MDa (8). Although there are ATPases in the 19S regulatory subunit of the 26S proteasome that may unfold substrates and allow them to enter through the pore (5, 6), AdV virions are much larger than any of the proteasome’s known cellular substrates. Because ADIN has been shown to be independent of autophagy but dependent on proteasomal degradation (3), we hypothesized that an additional energy-dependent step of AdV capsid disassembly and/or unfolding might precede proteasomal degradation of the virus.

In recent studies, the ATPase p97/VCP of the AAA (ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities) family has been implicated in the proteasomal degradation of certain cytosolic substrates (9–13). VCP is capable of dissociating proteins from large cellular structures such as the endoplasmic reticulum (14), the mitotic spindle (12), the nuclear envelope (15), and chromatin (16). VCP forms a homo-hexameric barrel-shaped ring of about 16 nm in diameter (17), a structure not dissimilar to the proteasome but without any associated protease activity. The N domain of VCP binds directly to multiubiquitin chains (18) and, although substrate ubiquitination does not seem to be a prerequisite for VCP interaction (19), a general role for VCP in unfolding ubiquitin-fusion degradation (UFD) substrates before proteasomal degradation has been suggested (20). Most recently, it has been shown that VCP is recruited to stalled proteasomes and relieves their (experimentally induced) impairment (21). It has been suggested that ATP hydrolysis–driven extraction of proteins from larger complexes or membranes, as well as unfolding of proteins by VCP upon recruitment to conjugated (poly)ubiquitin may be the common mechanism underlying the diverse cellular roles of VCP (13, 16, 22).

The energy-dependent, ubiquitin-selective segregase and unfoldase activity of VCP prompted us to investigate whether it has a role in ADIN. The results presented here demonstrate that VCP is an essential cofactor for ADIN and that the ATPase activity of VCP is required when ADIN mediates proteasomal degradation of a challenging substrate such as an adenovirus particle.

Results

Presence of VCP Is Essential for Intracellular Neutralization.

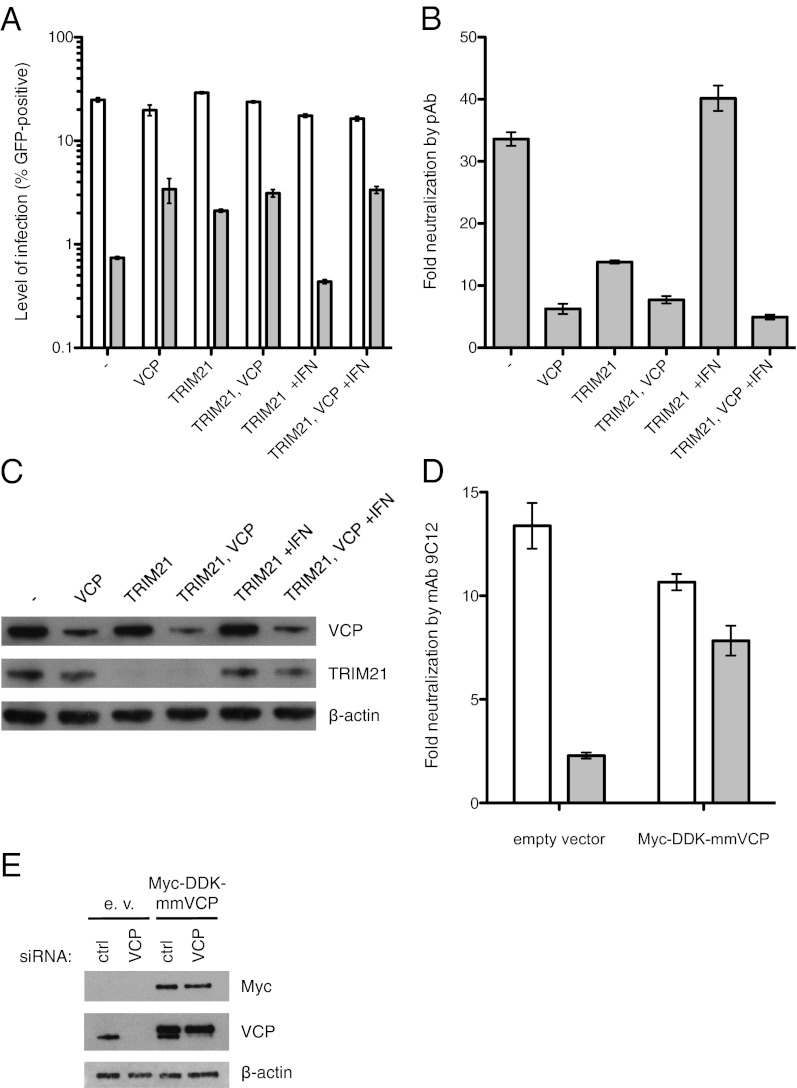

To determine whether VCP is involved in antibody-dependent intracellular neutralization of AdV, HeLa cells depleted of VCP, TRIM21, or both were infected with replication-deficient AdV type 5 encoding GFP (AdV-GFP) preincubated with or without a neutralizing polyclonal antibody (pAb). In cells transfected with control siRNA, pAb potently neutralized infection by 33-fold (Fig. 1 A and B). In cells depleted of VCP, neutralization was substantially reduced, to ∼sixfold (Fig. 1 A and B). Cells depleted of TRIM21 by shRNA also displayed significantly reduced neutralization; however, depletion of TRIM21 in VCP knockdown cells did not relieve neutralization further than knockdown of VCP alone. Depletion of TRIM21 or VCP does not completely abolish antibody neutralization, which we attribute to the presence of antibodies in the polyclonal serum that can neutralize by ADIN-independent mechanisms such as entry blocking. Importantly, however, depletion of VCP reverses all TRIM21-mediated neutralization, suggesting that TRIM21 and VCP operate in the same pathway. Treating TRIM21 shRNA cells with the immunostimulatory cytokine IFN-α 24 h before infection completely restored both TRIM21 levels (Fig. 1C) and neutralization [as seen previously (3, 23)], but this treatment had no effect on neutralization in cells that were also depleted of VCP (Fig. 1 A and B). This suggests that the presence of VCP is required for TRIM21-mediated neutralization of AdV by antibody.

Fig. 1.

VCP is essential for TRIM21-mediated neutralization of AdV by antibody. (A and B) Levels of infection of HeLa cells by AdV-GFP preincubated with (gray bars) or without (white bars) neutralizing polyclonal antibody (pAb) (A) and resulting neutralization of virus by antibody (B) are displayed for a set of conditions including RNA interference against VCP and/or TRIM21, as well as IFN treatment. (C) Protein levels in these conditions are visualized by Western blot. (D) Neutralization of virus by mAb 9C12 is shown for HeLa cells first transfected with control (white bars) or VCP siRNA (gray bars) and then transfected with empty vector or Myc-DDK–tagged mouse VCP (mmVCP). (E) Protein levels in these conditions visualized by Western blot. Data are represented as means ± SEM, calculated from three replicates.

Further evidence for a crucial role of VCP in ADIN was obtained by studying rescue of neutralization from VCP knockdown through overexpression of a coding sequence resistant to the siRNA. To this end, HeLa cells were first transfected with control siRNA or an siRNA targeting a sequence in the human VCP transcript that contains two substitutions with respect to mouse, and then transfected with empty vector or a plasmid encoding Myc-DDK–tagged mouse VCP (100% amino acid sequence conservation with respect to human). These cells were infected with AdV-GFP in the presence or absence of a neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb), 9C12, which has previously been shown to neutralize almost exclusively through ADIN (23). The mAb 9C12 potently neutralized infection in cells transfected with control siRNA and empty vector (Fig. 1D), whereas cells transfected with VCP siRNA were depleted of VCP (Fig. 1E) and displayed greatly diminished neutralization by mAb 9C12 (Fig. 1D). Transfection with the mouse VCP construct resulted both in robust overexpression of tagged VCP (Fig. 1E) and in rescue of the neutralization phenotype in cells depleted of endogenous VCP (Fig. 1D).

VCP ATPase Activity Is Required for ADIN.

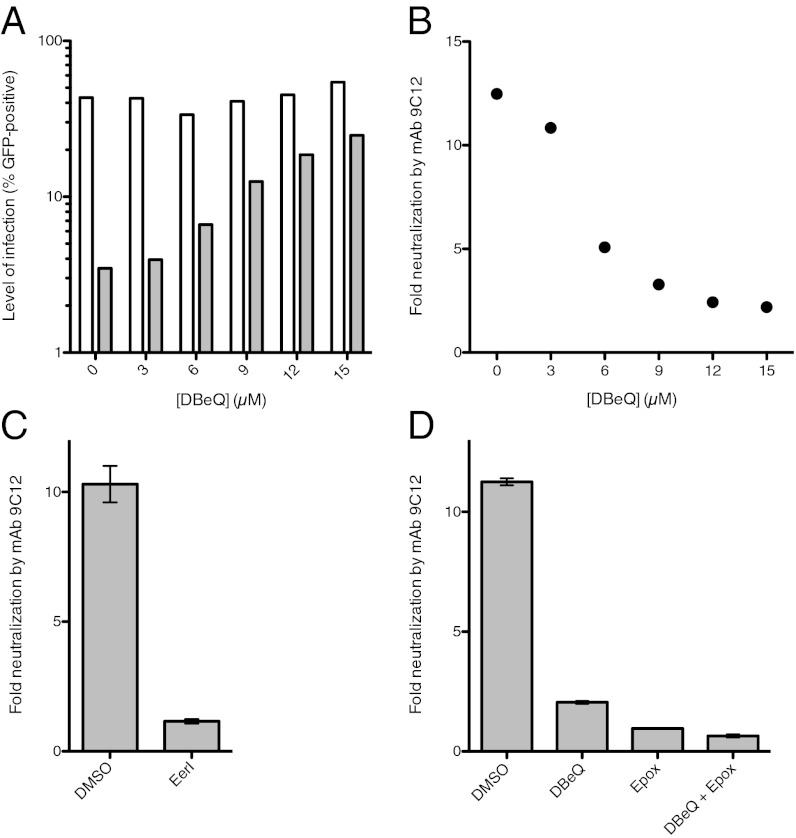

Next, the importance of VCP activity in ADIN was tested using specific chemical inhibitors. N2,N4-dibenzylquinazoline-2,4-diamine (DBeQ) was recently identified as a selective, potent, reversible, and ATP-competitive inhibitor of VCP (24). DBeQ was titrated onto HeLa cells at concentrations around its IC50 of 2.6 μM [as measured by Chou et al. (24) for VCP-dependent degradation of ubiquitinG76V-GFP, a UFD model substrate], and then cells were infected with AdV-GFP in the presence or absence of mAb 9C12. While mAb 9C12 potently neutralized infection in HeLa cells treated only with the solvent DMSO, treatment with DBeQ inhibited intracellular neutralization in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Neutralization was almost completely abrogated above 9 μM DBeQ, and higher concentrations of inhibitor had no further effect (Fig. 2B). This dose–response curve closely correlates with that previously published for in vitro inhibition of VCP ATPase activity (24). Importantly, in the absence of antibody, DBeQ had no effect on AdV infection (Fig. 2A). Further validation of these results was obtained by treating cells with Eeyarestatin (Eer)I, an irreversible inhibitor of VCP (25, 26). Similar to treatment with DBeQ or knockdown of VCP, treatment with 10 μM EerI before infection potently inhibited neutralization of AdV by mAb 9C12 (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the ATPase activity of VCP is crucial for intracellular neutralization of AdV by antibody.

Fig. 2.

Chemical inhibition of VCP abrogates ADIN and targets the same pathway as proteasome inhibition. (A and B) Levels of infection by AdV-GFP preincubated with (gray bars) or without (white bars) neutralizing mAb 9C12 (A) and resulting neutralization of virus by antibody (B) are displayed for HeLa cells treated with a titration of DBeQ. (C and D) Neutralization of virus by mAb 9C12 is shown for HeLa cells treated with DMSO, 10 μM EerI, 12 μM DBeQ, 2 μM epoxomicin (Epox), or both DBeQ and Epox. Data are represented as means ± SEM, calculated from three replicates.

To test whether VCP functions independently of or on pathway with the proteasome, we compared DBeQ and the irreversible proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin. Neutralization of AdV by mAb 9C12 was abrogated by treatment with 12 μM DBeQ or 2 μM epoxomicin (Fig. 2D). Combined treatment with both inhibitors had a similar effect to epoxomicin alone and was only marginally stronger compared with DBeQ alone. The absence of significant additive effects indicates that VCP and the proteasome operate on the same pathway of neutralization.

VCP Is Required for Proteasomal Degradation of Viral Capsid and Antibody in ADIN.

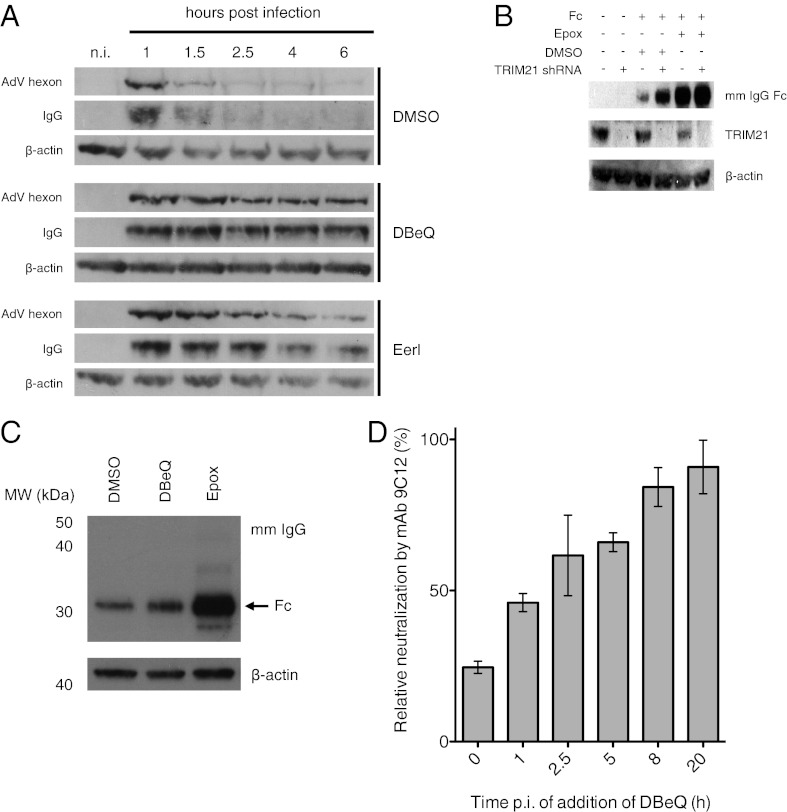

VCP is involved in the proteasomal degradation of a specific set of cellular substrates (13, 18, 20, 27). To investigate whether VCP is required for viral capsid degradation during ADIN, we performed a fate-of-capsid assay. Previously, we have used this assay to show that intracellular neutralization of AdV is accompanied by rapid degradation of hexon, the major adenovirus capsid component, and associated antibody. Degradation is inhibited by depletion of TRIM21 and significantly slowed by chemical inhibition of the proteasome (3). To determine the role of VCP in viral capsid degradation, HeLa cells treated with DMSO, 10 μM DBeQ, or 10 μM EerI were infected with AdV preincubated with mAb 9C12 and harvested at several time points between 1 and 6 h post infection (p.i.). As observed previously (3), both hexon and antibody were efficiently degraded within 2 h p.i. in DMSO-treated control cells (Fig. 3A, Top) to the extent where both were virtually undetectable after 2.5 h p.i. Both VCP inhibitors (DBeQ and EerI) potently inhibited degradation, with no detectable degradation of either hexon or antibody in DBeQ-treated cells during the entire 6-h period of the experiment (Fig. 3A, Middle and Bottom). These data suggest that VCP has a crucial role in proteasomal degradation of viral capsid.

Fig. 3.

VCP is required for degradation of virus and antibody in ADIN but not for TRIM21-mediated degradation of cytosolic IgG Fc. (A) Western blots of AdV hexon and mouse IgG levels in HeLa cells treated with DMSO, 10 μM DBeQ, or 10 μM EerI, infected with mAb 9C12-bound AdV, and harvested at indicated time points post infection. n.i., noninfected control. (B) Western blot of overexpressed mouse (mm) IgG Fc in HeLa cells with or without treatment with TRIM21 shRNA, DMSO, or 2 μM epoxomicin (Epox). (C) Western blot of overexpressed mm IgG Fc in HeLa cells treated with DMSO, 10 μM DBeQ, or 2 μM Epox. (D) Neutralization proceeds with similar kinetics as degradation. Relative neutralization of AdV-GFP by mAb 9C12 is displayed for HeLa cells treated with 9 μM DBeQ at several time points post infection (p.i.). Data were normalized to DMSO-treated control cells at each time point and are represented as means ± SEM, calculated from three replicates.

Requirement for VCP in ADIN Is Substrate-Specific.

Recent reports have suggested that VCP may be required when the proteasome faces a particularly challenging substrate (20) or when it becomes stalled by challenging amounts of substrate (21). We, therefore, investigated whether VCP is constitutively required for TRIM21-mediated degradation or whether its role is substrate-dependent. To test whether VCP is required for degradation of analogous but less challenging substrates than viral capsid, we established a model system based on overexpression of IgG Fc in HeLa cells. Given that TRIM21 binds to IgG with an affinity of ∼0.6 nM and mediates ubiquitination of antibody-bound objects in the cytosol to target them for degradation irrespective of their identity (3), it was expected that IgG Fc overexpressed in the cytosol would be degraded by the proteasome in a TRIM21-dependent fashion. Furthermore, IgG Fc could be considered the simplest substrate whose degradation would be mediated by TRIM21. Consistent with rapid degradation and turnover, relatively low levels of Fc were detected in Fc-overexpressing control cells. Importantly, levels of Fc were significantly increased when cells were depleted of TRIM21 by shRNA, treated with 2 μM epoxomicin, or both (Fig. 3B). However, addition of 10 μM DBeQ, which completely inhibited degradation of virus and antibody in the fate-of-capsid experiment, failed to prevent degradation of IgG Fc (Fig. 3C). This result suggests that the requirement for VCP is substrate-dependent and supports a hypothesis in which VCP is recruited to the proteasome upon processing of the viral capsid.

Mechanism of ADIN: Neutralization Is Intimately Linked to Degradation.

The results of the fate-of-capsid experiments shown here and in our previous study (3) suggest that ADIN prevents infection by catalyzing (premature) degradation of antibody-bound viral capsid. To test this hypothesis, we investigated whether degradation and neutralization proceed with similar kinetics. A time-of-addition assay was performed in which HeLa cells were synchronously infected with AdV-GFP by cold attachment, in the presence or absence of mAb 9C12, and treated with either DMSO or 9 μM DBeQ at a range of time points post infection. Addition of DBeQ concurrent with infection inhibited ADIN as potently as observed previously for pretreatment at the same concentration (Figs. 3D and 2B). However, the effect of DBeQ quickly diminished when the inhibitor was added at later time points post infection (Fig. 3D). The majority of neutralization occurred within the first 2.5 h p.i., as evidenced by the reduced effect of DBeQ when added after this time point. Thus, the majority of neutralization coincides with degradation of the majority of viral capsid observed in the fate-of-capsid assay (Fig. 3A). These findings support our model wherein proteasomal degradation, enabled by VCP, is the key effector mechanism of neutralization in ADIN.

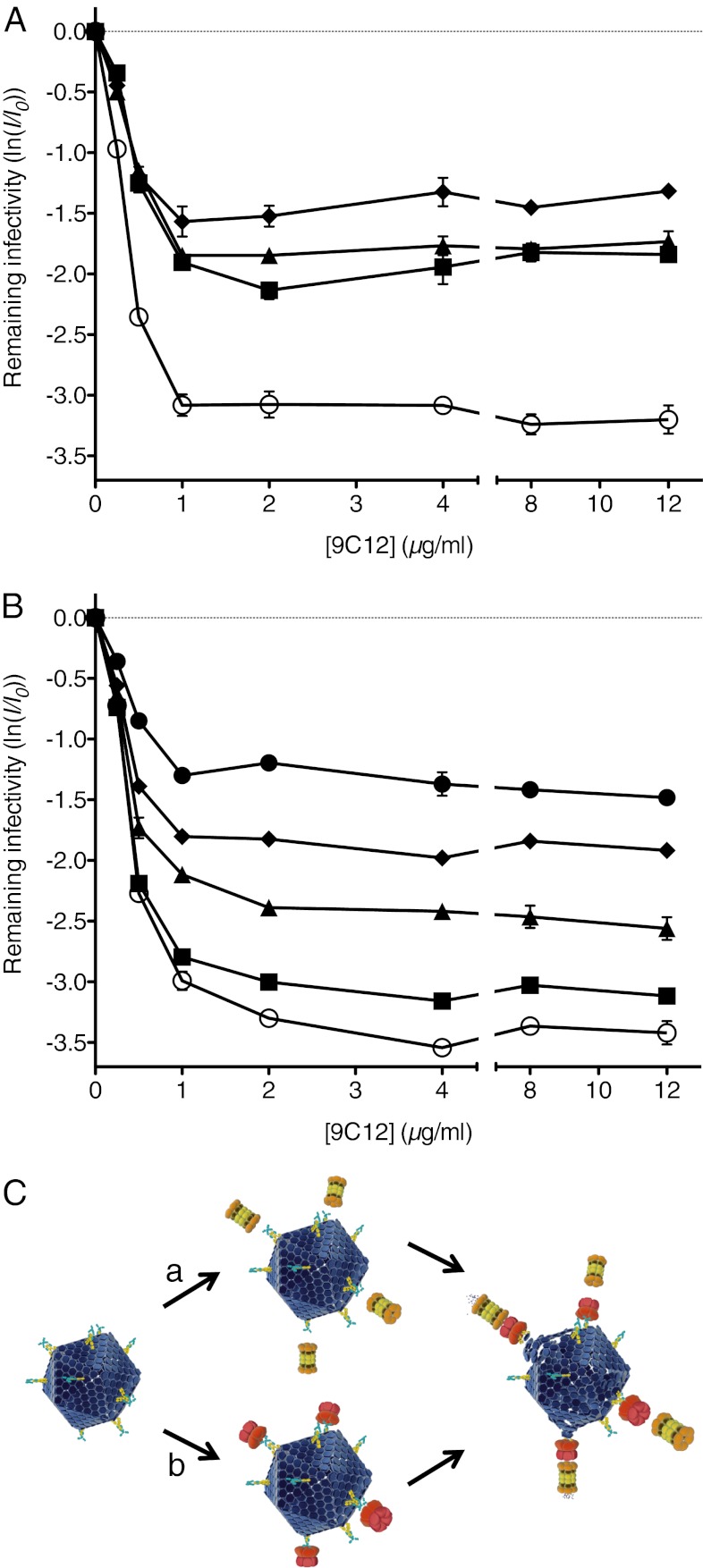

Both Efficiency and Potency of ADIN Depend on VCP.

Finally, we investigated the consequences of VCP perturbation on the efficiency of antibody neutralization and the level of persistent infection. AdV-GFP was preincubated with varying concentrations of mAb 9C12 before infection of HeLa cells that were subjected to RNA interference or to treatment with DBeQ. Both depletion of VCP by siRNA and depletion of TRIM21 by shRNA significantly reduced the initial gradient of neutralization as a function of antibody concentration (Fig. 4A), as did treatment with increasing concentrations of DBeQ (Fig. 4B). At high concentrations of mAb 9C12, where neutralization is maximal and further addition of antibody does not result in further neutralization (a phenomenon referred to as the persistent fraction of non-neutralized virus), depletion of VCP or TRIM21 led to a significant increase in the level of infection (Fig. 4A). Depleting TRIM21 knockdown cells of VCP did not greatly increase infection levels further, in agreement with these factors being on pathway. Furthermore, the level of persistent infection increased in a dose-dependent manner with increasing DBeQ concentration (Fig. 4B). These results show that without functioning VCP, a high proportion of cells become infected even at saturating levels of neutralizing antibody 9C12. It is, therefore, noteworthy that VCP is a very abundant protein (28, 29), suggesting that even though it is not IFN-inducible, it is unlikely to become rate-limiting even at high multiplicities of infection.

Fig. 4.

VCP is essential for efficient and potent ADIN. (A and B) Relative levels of infection of HeLa cells by AdV-GFP in several conditions as a function of concentration of neutralizing mAb 9C12 that the virus was preincubated with: negative control siRNA (open circles), VCP siRNA (squares), TRIM21 shRNA and negative control siRNA (triangles), and TRIM21 shRNA and VCP siRNA (diamonds) (A); and DMSO (open circles), 3 μM DBeQ (squares), 4.5 μM DBeQ (triangles), 6 μM DBeQ (diamonds), and 9 μM DBeQ (closed circles) (B). Data are represented as means ± SEM, calculated from three replicates. (C) Proposed VCP-dependent mechanism of ADIN. In the cytoplasm, antibody-bound AdV is detected and engaged by TRIM21. The proteasome and VCP are recruited and mediate degradation of viral capsid and antibody, leading to neutralization. AdV is in dark blue, antibody is in yellow, TRIM21 is in cyan, proteasome is in orange/brown/yellow (19S regulatory particles omitted for simplicity), and VCP is in red. AdV, proteasome, and VCP are represented to scale.

Discussion

Our data show that TRIM21-mediated intracellular neutralization of AdV by antibody depends on the presence and activity of AAA ATPase VCP. This discovery elucidates a crucial aspect of ADIN, namely the disassembly and degradation of a large and compact viral capsid. The activity of VCP is shown here to be required for proteasomal degradation of AdV and antibody. This degradation is a key step in neutralization and occurs within the first few hours of infection. In consequence, reducing cellular levels of VCP by RNA interference or inhibiting its ATPase activity with specific chemical inhibitors severely diminishes neutralization of AdV by antibody.

Several mechanistic hypotheses have been proposed to explain the role of VCP in proteasomal degradation of cellular substrates. It has been suggested that VCP may be required for initial unfolding of tightly folded substrates that lack an intrinsically unstructured region as initiation site for the proteasome (20). The AdV capsid may qualify as such a substrate (8, 30). Alternatively, the direct but highly transient interaction between VCP and the proteasome (31) may be specifically stabilized when the proteasome faces a particularly challenging substrate or when it is otherwise impaired. The latter hypothesis was suggested in a recent study analyzing the association of VCP with proteasomes in various stress conditions that induce the unfolded protein response (21).

We propose that in ADIN, VCP is specifically recruited during proteasomal degradation of a large virion. Our finding that proteasomal degradation of free IgG Fc does not depend on VCP supports this substrate-specific rather than constitutive role for VCP. During degradation of virus, VCP may mediate ATP hydrolysis-driven disassembly and/or partial unfolding of the AdV capsid, enabling the 19S regulatory particle to pass capsid components (and the associated antibody) into the 20S core particle for degradation (Fig. 4C, route a). However, our results do not rule out the alternative possibility that VCP is recruited to the ubiquitin-positive ADIN complex of AdV, antibody, and TRIM21 before engagement of the proteasome to mediate processing upstream of degradation (Fig. 4C, route b). Future studies such as high-resolution time-resolved microscopy may help to clarify the mechanism in detail.

A direct role for VCP in the physical destruction of virus is supported by our fate-of-capsid experiments, in which VCP inhibition by DBeQ completely abrogates degradation of virus and antibody. Furthermore, we have made use of DBeQ to demonstrate that it is the degradation of virus that drives neutralization. In time-of-addition experiments, we find that the kinetics of neutralization correlate closely with the kinetics of degradation. When viral degradation is blocked by VCP inhibition within the first few hours post infection, productive infection proceeds.

A number of recent studies have shown that VCP is also required for autophagy (32, 33), with the exact mechanism still subject of debate (34). Although depleting or inhibiting VCP is, thus, bound to impact this process, we consider impairment of autophagy unlikely to underlie the requirement for VCP in ADIN, since specific inhibition of the proteasome abrogates intracellular neutralization entirely [Fig. 2D and previous work (3)], whereas inhibiting autophagy using 3-methyladenine has no effect (3). Of note, however, there is increasing evidence for crosstalk and coordination between the ubiquitin–proteasome system and autophagy, and VCP has been proposed to play a role at their interface (34, 35). We, therefore, cannot rule out that our perturbations of VCP and the proteasome elicit a complex cellular phenotype.

In summary, we have identified the AAA ATPase VCP as an essential enzyme in ADIN. Our results support recent studies linking VCP to proteasomal degradation and, at the same time, suggest that VCP may play an important role in immunity, in addition to its documented roles in cell biology. Finally, it is tempting to speculate that while ADIN makes use of the segregase, unfoldase, and degradation-associated functions of VCP to neutralize virus, some viruses may have evolved to exploit the same activities for productive uncoating and infection.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Production of Viruses.

All cell lines were maintained as described previously (3). For depletion of TRIM21, HeLa cells were stably transduced with shRNA-encoding retroviral vector pSIREN-T21. To deplete VCP, HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides VCPHSS111263, VCPHSS111264, and VCPHSS187663 (Invitrogen) or J-008727-12 (Dharmacon; used in Fig. 1 D and E) against human VCP or with Silencer Negative Control siRNA #1 (Ambion). For overexpression of mouse VCP, HeLa cells were transiently transfected with a plasmid encoding the Myc-DDK–tagged protein (MR210760, OriGene) or with empty vector. Replication-deficient, E1-deleted GFP-expressing human adenovirus 5 (36) was prepared by CsCl centrifugation.

Antibodies and Other Reagents.

Anti-AdV hexon mouse monoclonal antibody 9C12 (37, 38) was purified from hybridoma supernatant on a protein-G column (GE Healthcare). Other antibodies used included goat polyclonal anti-AdV hexon (AB1056; Millipore), mouse monoclonal anti-VCP/p97 ATPase (MA1-21412; Thermo Scientific), mouse monoclonal D-12 anti-TRIM21 (sc-25351; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti–β-actin (4967; Cell Signaling), donkey anti-mouse IgG (AP192; Millipore), HRP-conjugated mouse monoclonal 9E10 anti–c-Myc (ab62928; Abcam), HRP-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (sc-2056; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG (A0168 and A9169; Sigma Aldrich). HRP-conjugated protein A was obtained from BD Biosciences. DBeQ was purchased from BioVision, EerI from Tocris Bioscience, and epoxomicin from Calbiochem. All chemical inhibitors were dissolved in DMSO.

Virus Neutralization Assays.

Virus neutralization assays were performed essentially as described previously (3). Transfections with siRNA were performed 72 h before infection, and transfections with plasmids were performed 30 h before infection. When used, DMSO, the proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin (2 μM), or the irreversible VCP inhibitor EerI (10 μM) was added to cells for 1–5 h before medium exchange and infection. In experiments with the reversible VCP inhibitor, DBeQ was added to cells 90 min before infection (unless indicated otherwise, in the time-of-addition assay) and was kept on cells until harvesting. Virus:antibody mixtures were added to cells at a multiplicity of infection of 0.2–0.4. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C cells were harvested, fixed in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde/PBS and analyzed on a BD LSRII Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data analysis was carried out in FlowJo (Tree Star).

Fate-of-Capsid Assay.

HeLa cells (2 × 105 per well) were seeded in six-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight. DMSO, 10 μM DBeQ, or 10 μM EerI was added to respective wells 2 h before infection; EerI was then removed, whereas DMSO and DBeQ remained on cells until harvesting. AdV-GFP (4 × 107 IU/well) was mixed with an equal volume of 110 μg/mL mAb 9C12 in a total volume of 50 μL per well, incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and then added onto cells. Infections were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min before medium was exchanged. Cells were harvested at indicated time points after addition of virus (referred to as infection) and boiled in 50 μL per well of NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen) supplemented with reducing agent. AdV hexon was detected with polyclonal goat anti-hexon and HRP-conjugated anti-goat IgG. Antibody was detected with anti-mouse IgG and HRP–protein A.

Fc Degradation Assays.

Briefly, HeLa cells or HeLa cells depleted of TRIM21 by shRNA were transiently transfected with pCMV6-AN-Fc plasmid (PS100055; OriGene) for cytosolic overexpression of murine IgG Fc; treated with DMSO, 2 μM epoxomicin, or 10 μM DBeQ 24 h later; and harvested for Western Blot analysis after an additional 24 h.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Watkinson for purification of mAb 9C12, L. McKeane for illustrations, and A. Guo for invaluable support. This work was funded by Medical Research Council Grant U105181010 and European Research Council Grant 281627-IAI. F.H. is supported by a Kekulé Mobility Fellowship from the Chemical Industry Fund of the German Chemical Industry Association.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 19517.

References

- 1.James LC, Keeble AH, Khan Z, Rhodes DA, Trowsdale J. Structural basis for PRYSPRY-mediated tripartite motif (TRIM) protein function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(15):6200–6205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609174104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keeble AH, Khan Z, Forster A, James LC. TRIM21 is an IgG receptor that is structurally, thermodynamically, and kinetically conserved. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(16):6045–6050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800159105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mallery DL, et al. Antibodies mediate intracellular immunity through tripartite motif-containing 21 (TRIM21) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(46):19985–19990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014074107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McEwan WA, Mallery DL, Rhodes DA, Trowsdale J, James LC. Intracellular antibody-mediated immunity and the role of TRIM21. Bioessays. 2011;33(11):803–809. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voges D, Zwickl P, Baumeister W. The 26S proteasome: A molecular machine designed for controlled proteolysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:1015–1068. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallastegui N, Groll M. The 26S proteasome: Assembly and function of a destructive machine. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35(11):634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie Y. Structure, assembly and homeostatic regulation of the 26S proteasome. J Mol Cell Biol. 2010;2(6):308–317. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy VS, Natchiar SK, Stewart PL, Nemerow GR. Crystal structure of human adenovirus at 3.5 A resolution. Science. 2010;329(5995):1071–1075. doi: 10.1126/science.1187292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexandru G, et al. UBXD7 binds multiple ubiquitin ligases and implicates p97 in HIF1alpha turnover. Cell. 2008;134(5):804–816. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao K, Nakajima R, Meyer HH, Zheng Y. The AAA-ATPase Cdc48/p97 regulates spindle disassembly at the end of mitosis. Cell. 2003;115(3):355–367. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00815-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu X, Ng C, Feng D, Liang C. Cdc48p is required for the cell cycle commitment point at Start via degradation of the G1-CDK inhibitor Far1p. J Cell Biol. 2003;163(1):21–26. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janiesch PC, et al. The ubiquitin-selective chaperone CDC-48/p97 links myosin assembly to human myopathy. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(4):379–390. doi: 10.1038/ncb1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer H, Bug M, Bremer S. Emerging functions of the VCP/p97 AAA-ATPase in the ubiquitin system. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(2):117–123. doi: 10.1038/ncb2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bays NW, Wilhovsky SK, Goradia A, Hodgkiss-Harlow K, Hampton RY. HRD4/NPL4 is required for the proteasomal processing of ubiquitinated ER proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12(12):4114–4128. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.12.4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hetzer M, et al. Distinct AAA-ATPase p97 complexes function in discrete steps of nuclear assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(12):1086–1091. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramadan K, et al. Cdc48/p97 promotes reformation of the nucleus by extracting the kinase Aurora B from chromatin. Nature. 2007;450(7173):1258–1262. doi: 10.1038/nature06388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, et al. Structure of the AAA ATPase p97. Mol Cell. 2000;6(6):1473–1484. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai RM, Li CC. Valosin-containing protein is a multi-ubiquitin chain-targeting factor required in ubiquitin-proteasome degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(8):740–744. doi: 10.1038/35087056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye Y, Meyer HH, Rapoport TA. The AAA ATPase Cdc48/p97 and its partners transport proteins from the ER into the cytosol. Nature. 2001;414(6864):652–656. doi: 10.1038/414652a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beskow A, et al. A conserved unfoldase activity for the p97 AAA-ATPase in proteasomal degradation. J Mol Biol. 2009;394(4):732–746. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isakov E, Stanhill A. Stalled proteasomes are directly relieved by P97 recruitment. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(35):30274–30283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.240309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shcherbik N, Haines DS. Cdc48p(Npl4p/Ufd1p) binds and segregates membrane-anchored/tethered complexes via a polyubiquitin signal present on the anchors. Mol Cell. 2007;25(3):385–397. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McEwan WA, et al. 2012. Regulation of virus neutralization and the persistent fraction by TRIM21. J Virol 86(16):8482–8491.

- 24.Chou TF, et al. Reversible inhibitor of p97, DBeQ, impairs both ubiquitin-dependent and autophagic protein clearance pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(12):4834–4839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015312108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q, Li L, Ye Y. Inhibition of p97-dependent protein degradation by Eeyarestatin I. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(12):7445–7454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708347200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Q, et al. The ERAD inhibitor Eeyarestatin I is a bifunctional compound with a membrane-binding domain and a p97/VCP inhibitory group. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):e15479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wójcik C, et al. Valosin-containing protein (p97) is a regulator of endoplasmic reticulum stress and of the degradation of N-end rule and ubiquitin-fusion degradation pathway substrates in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(11):4606–4618. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters JM, Walsh MJ, Franke WW. An abundant and ubiquitous homo-oligomeric ring-shaped ATPase particle related to the putative vesicle fusion proteins Sec18p and NSF. EMBO J. 1990;9(6):1757–1767. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pleasure IT, Black MM, Keen JH. Valosin-containing protein, VCP, is a ubiquitous clathrin-binding protein. Nature. 1993;365(6445):459–462. doi: 10.1038/365459a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu H, et al. Atomic structure of human adenovirus by cryo-EM reveals interactions among protein networks. Science. 2010;329(5995):1038–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1187433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Besche HC, Haas W, Gygi SP, Goldberg AL. Isolation of mammalian 26S proteasomes and p97/VCP complexes using the ubiquitin-like domain from HHR23B reveals novel proteasome-associated proteins. Biochemistry. 2009;48(11):2538–2549. doi: 10.1021/bi802198q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ju JS, et al. Valosin-containing protein (VCP) is required for autophagy and is disrupted in VCP disease. J Cell Biol. 2009;187(6):875–888. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tresse E, et al. VCP/p97 is essential for maturation of ubiquitin-containing autophagosomes and this function is impaired by mutations that cause IBMPFD. Autophagy. 2010;6(2):217–227. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.2.11014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dargemont C, Ossareh-Nazari B. Cdc48/p97, a key actor in the interplay between autophagy and ubiquitin/proteasome catabolic pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823(1):138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ju JS, Weihl CC. p97/VCP at the intersection of the autophagy and the ubiquitin proteasome system. Autophagy. 2010;6(2):283–285. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.2.11063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Martin R, Raidl M, Hofer E, Binder BR. Adenovirus-mediated expression of green fluorescent protein. Gene Ther. 1997;4(5):493–495. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith JG, Cassany A, Gerace L, Ralston R, Nemerow GR. Neutralizing antibody blocks adenovirus infection by arresting microtubule-dependent cytoplasmic transport. J Virol. 2008;82(13):6492–6500. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00557-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varghese R, Mikyas Y, Stewart PL, Ralston R. Postentry neutralization of adenovirus type 5 by an antihexon antibody. J Virol. 2004;78(22):12320–12332. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12320-12332.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]