Abstract

The induction of broadly reacting neutralizing antibodies has been a major goal of HIV vaccine research. Characterization of a pathogenic CCR5 (R5)-tropic SIV/HIV chimeric virus (SHIV) molecular clone (SHIVAD8-EO) revealed that eight of eight infected animals developed cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) directed against an envelope glycoprotein derived from the heterologous HIV-1DH12 strain. A panel of plasmas, collected from monkeys inoculated with either molecularly cloned or uncloned SHIVAD8 stocks, exhibited cross-neutralization against multiple tier 1 and tier 2 HIV-1 clade B isolates. One SHIVAD8-infected animal also developed NAbs against clades A and C HIV-1 strains. In this particular infected macaque, the cross-reacting anti–HIV-1 NAbs produced between weeks 7 and 13 were directed against a neutralization-sensitive virus strain, whereas neutralizing activities emerging at weeks 41–51 targeted more neutralization-resistant HIV-1 isolates. These results indicate that the SHIVAD8 macaque model represents a potentially valuable experimental system for investigating B-cell maturation and the induction of cross-reactive NAbs directed against multiple HIV-1 strains.

A major challenge in HIV vaccine research has been the development of immunogens capable of eliciting potent, broadly acting, neutralizing antibodies (NAbs). It is now appreciated that 10–30% of HIV-1–infected individuals produce cross-reactive NAbs of significant breadth (1–6). Less than 1% of such persons, so-called “elite neutralizers,” produce potent cross-clade–neutralizing activity, but only 2–3 y after virus acquisition (6). Although the emergence of broadly reacting anti–HIV-1 NAbs in elite neutralizers has been associated with multiple rounds of somatic hypermutation (7), little is known about vaccine strategies able to elicit such antibodies. Longitudinal studies of HIV-1– infected persons have suggested that set-point plasma virus loads, CD4+ T-cell levels, duration of the infection, or antibody-binding avidity may contribute to the development of cross-reacting NAbs (5, 8, 9). It is also possible that the induction of such antibodies depends on unique gp120 epitopes associated with specific HIV-1 strains and individual B-cell repertoires or is simply a random process (10, 11). A nonhuman primate model capable of generating cross-reactive anti–HIV-1–neutralizing activity could provide answers to some of these questions and contribute to the development of an effective prophylactic vaccine. In this regard, we recently reported that one rhesus monkey, inoculated with an uncloned preparation of the R5-tropic SHIVAD8, developed broad, potent, and glycan-specific NAbs with cross-reacting activity against virus isolates from different HIV-1 clades similar to that described for “elite” HIV-1 neutralizers (12).

In this study, we describe the construction of a pathogenic SHIVAD8 molecular clone (SHIVAD8-EO). During its characterization, we discovered that eight of eight SHIVAD8-EO–infected animals generated cross-reactive NAbs directed against a SHIV carrying an envelope glycoprotein derived from a different HIV-1 isolate (namely HIV-1DH12). Because this result suggested that a majority of monkeys infected with the SHIVAD8-EO family of viruses might be able to generate NAbs against heterologous HIV-1 isolates, plasma samples collected from a cohort of 11 rhesus macaques, infected with either uncloned SHIVAD8 swarm stocks or SHIVAD8 molecular clones, were tested for their capacity to neutralize a panel of clade A, B, and C HIV-1 isolates. All of the plasmas from this group of 11 animals neutralized several tier 1A and 1B clade B HIV-1 strains. Three of the 11 macaques also generated >1:100 IC50 neutralization titers against some tier 2 clade B HIV-1 isolates, and one of the three produced significant NAb titers against some clade A and C isolates. Taken together, these findings indicate that SHIVAD8 is uniquely immunogenic during infections of rhesus monkeys and may be a particularly useful reagent for identifying viral determinants that drive B-cell maturation resulting in cross-reactive anti–HIV-1 NAbs.

Results

Infection of Rhesus Monkeys with the SHIVAD8-EO Molecular Clone.

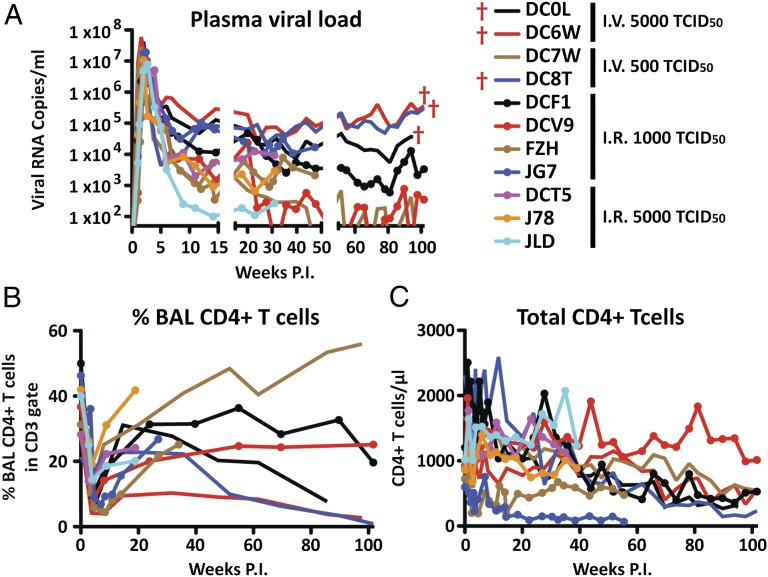

Although we had previously reported the construction and characterization of the R5-tropic SHIVAD8 and had prepared uncloned SHIVAD8 swarm stocks as challenge viruses for vaccine experiments (13, 14), we had not obtained a pathogenic SHIVAD8 molecular clone, capable of durably maintaining chronic virus infection and inducing clinical immunodeficiency in inoculated animals. This was accomplished, as described in Materials and Methods, by amplifying SHIVAD8 vpu and env genes from the plasmas of several SHIVAD8–infected monkeys and inserting individual amplicons into the genetic background of SIVmac239 (Figs. S1 and S2). One of the resulting clones (SHIVAD8-EO) exhibiting robust replication kinetics in cultured rhesus peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) was inoculated into 11 animals: 4 by the i.v. (5,000 or 500 TCID50) and 7 by the intrarectal (5,000 or 1,000 TCID50) routes. Similar to uncloned SHIVAD8 derivatives (13, 14), the levels of set point viremia in macaques infected with the SHIVAD8-EO molecular clone varied widely (102 to >105 RNA copies/mL) (Fig. 1A). Memory CD4+ T cells at an effector site [recovered by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)] declined markedly in all of the monkeys during the acute phase of the SHIVAD8-EO infection (Fig. 1B), and a gradual loss of total circulating CD4+ T cells occurred in most animals (Fig. 1C). Monkey DC0L was euthanized at week 95 post infection (PI) with clinical symptoms of immunodeficiency following protracted anorexia and diarrhea that was accompanied by marked weight loss. Macaque DC6W also experienced marked weight loss and was euthanized at week 111 with a gastric lymphoma. Macaque CD8T was euthanized at week 117 with multiple intra-abdominal lymphomas.

Fig. 1.

Virus replication and CD4+ T-cell dynamics in rhesus macaques inoculated i.v. or intrarectally with the molecularly cloned SHIVAD8-EO. The levels of plasma viremia (A), percentage of BAL fluid CD4+ T cells (B), and absolute numbers of circulating CD4+ T cells (C) are shown.

Neutralizing Antibodies Generated in SHIVAD8-Infected Macaques.

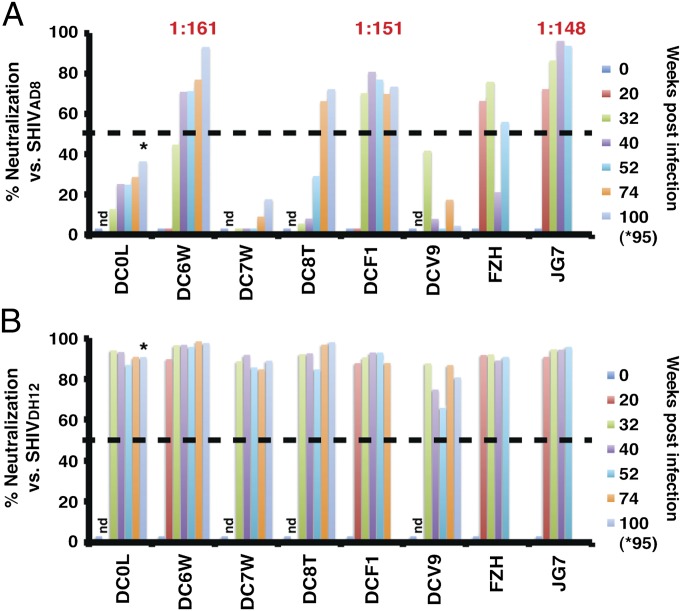

We recently reported that only 3 of 19 macaques inoculated with SHIVAD8 swarm viruses developed sustained levels of autologous Nabs (13). In the current study, autologous NAbs, developing in eight of the macaques infected with the SHIVAD8-EO molecular clone were initially assessed using plasma samples diluted 1:20. As shown in Fig. 2A, five of the eight animals produced autologous neutralizing activity (>50% neutralization). In four of these macaques (DC6W, DCF1, FZH, and JG7), autologous NAbs became measurable between weeks 20 and 40 PI, but were delayed until week 74 in the fifth (DC8T) animal. Individual samples from three of these monkeys (DC6W, DCF1, and JG7) had autologous neutralization IC50 titers ranging from 1:148 to 1:161.

Fig. 2.

Autologous and cross-reacting NAbs produced by animals infected with the molecularly cloned SHIVAD8-EO. Plasma samples from the indicated SHIVAD8-EO–infected macaques were collected at different times post infection, diluted 1:20, and assayed for neutralizing activity against the autologous SHIVAD8 (A) or the heterologous SHIVDH12 (B). The dashed line in each panel at 50% neutralization represents the threshold of virus suppression in the TZM-bl cell assay. The IC50 neutralization titers determined for plasmas collected from macaques DC6W (week 52), DCF1 (week 40), and JG7 (week32) were determined by reciprocal dilution and assay in TZM-bl cells. Asterisks indicate NAbs detected at week 95. nd: not done.

In an earlier study, we reported that one rhesus monkey inoculated with uncloned SHIVAD8 developed extraordinarily broad, cross-clade, and high-titered NAbs similar to that described for HIV-1 “elite neutralizers” (12). This potent neutralizing activity targeted the gp120 N332 glycan. Because we were curious whether animals infected with the SHIVAD8-EO molecular clone might also produce antibodies able to neutralize a heterologous HIV-1 isolate, plasma samples (1:20 dilution) from the same eight SHIVAD8-EO–infected monkeys were tested for their capacity to neutralize pseudovirions bearing the CXCR4 (X4)-tropic SHIVDH12-CL7 envelope glycoprotein, originally derived from the HIV-1DH12 isolate (15–17). The HIV-1–derived env genes present in SHIVAD8-EO and SHIVDH12-CL7 are 90% and 84% identical at the level of nucleotide and amino acid sequences, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2B, all eight plasmas, including samples from animals (DC0L, DC7W, and DCV9) with no or extremely low autologous NAbs, exhibited neutralizing activity against SHIVDH12.

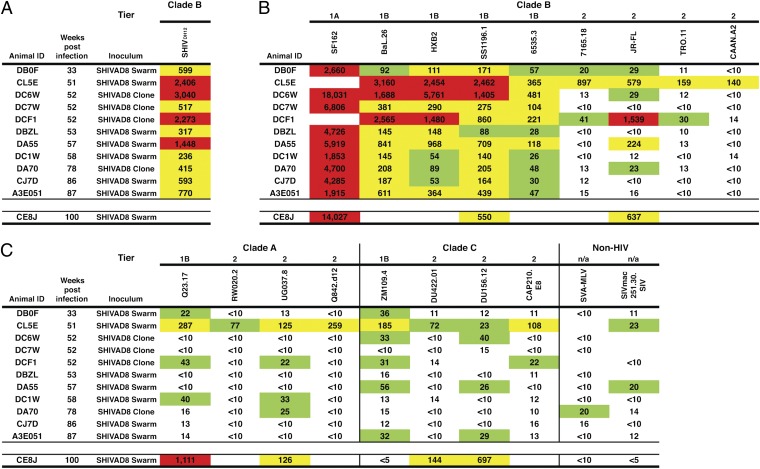

We next determined the cross-reactive IC50 NAb titers directed against SHIVDH12 present in the plasmas of a different cohort of 11 macaques, which had been inoculated with molecularly cloned SHIVAD8 or recently described SHIVAD8 swarm stocks (13) (Fig. 3A). Only 4 (macaques DC6W, DCF1, DA55, DA70) of these 11 SHIVAD8–infected animals had developed autologous NAbs. Nonetheless, the plasmas from all 11 SHIVAD8–infected animals generated anti-SHIVDH12 neutralizing IC50 titers (ranging from 1:236 to 1:3,040).

Fig. 3.

Macaques infected with uncloned or molecularly cloned SHIVAD8 viruses develop cross-reacting NAbs against multiple HIV-1 strains. IC50 neutralization titers against the highly sensitive SHIVDH12 (A), the indicated clade B (B) and clade A and C (C) HIV-1 isolates in plasmas of a cohort of 11 SHIVAD8–infected animals were determined by reciprocal dilution and assay in TZM-bl cells. Values represent reciprocal serum dilution required to achieve 50% neutralization. The previously reported (12) neutralizing activity of week 100 plasma from animal CE8J is shown at the bottom of each panel. Value between 20 and 99, green; value between 100 and 999, yellow; value ≥1,000, red. Blank cell indicates that value was not determined.

The production of cross-reacting NAbs against SHIVDH12 by SHIVAD8–infected monkeys raised the possibility that a similar activity might have also been generated against other HIV-1 isolates. Plasma samples from the same cohort of 11 animals, infected with the molecularly cloned or uncloned SHIVAD8 viruses, were assessed for their capacity to neutralize a panel of clade A, B, and C HIV-1 strains. As shown in Fig. 3 B and C, plasmas from all of the monkeys possessed neutralizing activity against tier 1A (very high sensitivity) and tier 1B (above-average sensitivity) clade B HIV-1 isolates (18). In addition, three of the macaques (CL5E, DCF1, and DA55) generated >1:100 IC50 NAb titers against some tier 2 (moderate sensitivity) clade B HIV-1 strains (HIV-1JR-FL, HIV-176515, HIV-1TRO.11, and HIV-1CAAN.A2). The plasma from monkey CL5E exhibited the widest breadth, including neutralization activity against clade A and C HIV-1 strains. A neutralization profile for the previously reported (12) “elite neutralizer” macaque CE8J at the time of its euthanasia at week 100 PI is also shown at the bottom of Fig. 3.

In the context of the neutralization phenotypes shown in Fig. 3, SHIVDH12 ranks with several highly neutralization-sensitive clade B HIV-1 strains. However, when its sensitivity was evaluated against a panel of standardized plasma pools from HIV-1 infected individuals (18), SHIVDH12 exhibited a tier 2 neutralization phenotype (Table S1).

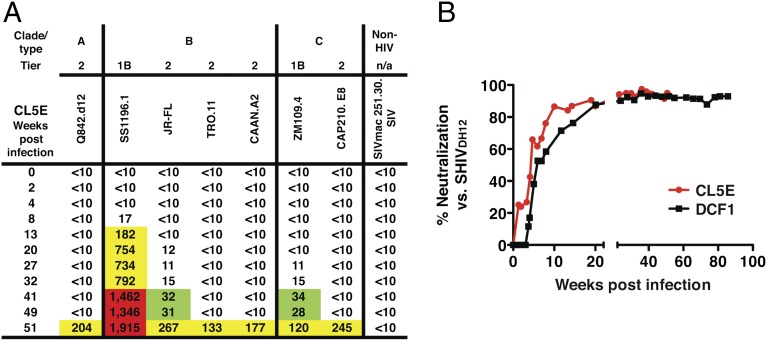

To ascertain whether the temporal appearance of cross-reacting NAbs directed against the more difficult-to-neutralize tier 2 HIV-1 strains occurred at the same time as neutralizing activity against tier 1 isolates in macaque CL5E (Fig. 3), the IC50 neutralization titers present in plasma samples collected at various times following SHIVAD8 inoculation of this animal were determined. Surprisingly, significant levels of neutralizing activity became detectable only against the tier 1B HIV-1SS1196.1 strain by week 13 PI (Fig. 4A). NAbs directed against three tier 2 clade B HIV-1 isolates or clade A and C HIV-1 strains all emerged between weeks 41 and 51 PI. In an independent experiment, cross-reacting NAbs directed against the highly neutralization-sensitive SHIVDH12 appeared between weeks 7–10 PI in two representative SHIVAD8–infected monkeys (Fig. 4B). Taken together, these results suggest that SHIVAD8–infected macaques may produce cross-reactive neutralization activity in one or two phases of the infection: (i) at early times (weeks 7–13 PI), a majority of animals may generate high titers against relatively neutralization-sensitive tier 1A and tier 1B HIV-1 strains; and (ii) several months later, some monkeys also develop NAbs able to suppress the more difficult-to-neutralize tier 2 clade B or clade A and C HIV-1 isolates.

Fig. 4.

Rhesus monkeys generate cross-reactive NAbs during two phases of the SHIVAD8 infection. (A) The IC50 neutralization titers in plasma samples collected at various times from macaque CL5E against the indicated HIV-1 strains were determined by reciprocal dilution and assay in TZM-bl cells. Values represent reciprocal serum dilution required to achieve 50% neutralization. Value between 20 and 99, green; value between 100 and 999, yellow; value ≥1,000, red. (B) Cross-reactive anti-SHIVDH12 NAbs rapidly develop in two representative SHIVAD8–infected animals. Plasma samples, collected from SHIVAD8–infected macaques DCF1 or CL5E at the indicated times, were diluted 1:20 and assayed for neutralizing activity against pseudovirions carrying the SHIVDH12-CL-7 (15) envelope glycoprotein in TZM-bl cells.

SHIVs Bearing the HIV-1AD8 Envelope Glycoprotein Are More Efficient in Generating Cross-Reacting NAbs than a SHIV Expressing the HIVDH12 env Gene During Infections of Rhesus Macaques.

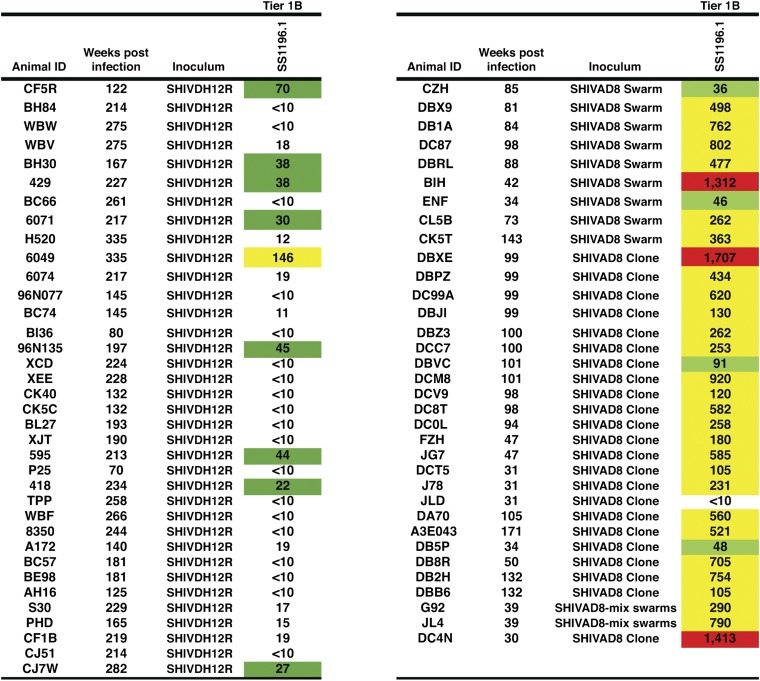

Two earlier studies have reported cross-reactive anti–HIV-1–neutralizing activity developing in a small fraction of SHIV–inoculated animals during the chronic phase of their infections (19, 20). The availability of preserved plasma samples from large cohorts of the X4-tropic SHIVDH12–infected monkeys (36 animals) or the R5-tropic SHIVAD8–infected monkeys (34 animals not evaluated in Fig. 3) provided the opportunity to directly compare the levels of cross-reacting plasma-neutralizing activity generated in macaques inoculated with SHIVDH12 or SHIVAD8 against a common heterologous tier 1B clade B HIV-1 isolate (HIV-1SS1196.1) (21). As shown in Fig. 5, only 1 of 36 SHIVDH12–infected animals generated IC50 NAb titers >1:100 (a titer of 1:146) against HIV-1SS1196.1 compared with 29 of 34 SHIVAD8–infected macaques (titers ranging from 1:105 to 1:1,707) against HIV-1SS1196.1. In this single head-to-head comparison, the SHIVAD8 envelope glycoprotein, expressed during in vivo infections, was clearly superior in eliciting cross-reactive anti–HIV-1 NAbs.

Fig. 5.

SHIVAD8 is far superior to SHIVDH12 in eliciting potent cross-reactive NAbs during infections of rhesus macaques. Anti–HIV-1SS1196.1 IC50 neutralizing titers in plasma collected from the indicated infected monkeys were determined by reciprocal dilution and assay in TZM-bl cells. Values represent reciprocal serum dilution required to achieve 50% neutralization. Value between 20 and 99, green; value between 100 and 999, yellow; value ≥1,000, red.

Discussion

The most unique and unexpected property of the SHIVAD8 family of viruses revealed in this study was its capacity to induce cross-reactive anti–HIV-1 NAbs in a majority of infected animals. Monkey CL5E, which produced NAbs against clade A, B, and C HIV-1 strains, and macaques DCF1 and DA55, which generated IC50-neutralizing titers >1:100 against the tier 2 HIV-1JR-FL isolate, represent three SHIVAD8–infected animals that developed cross-reacting NAb responses of significant breadth. Unlike the development of NAbs in many HIV-1–infected persons (22–24), macaques infected with the SHIVAD8 family of viruses generated cross-reactive NAbs well before or in lieu of autologous NAbs.

There have been at least two earlier studies reporting that some SHIV–infected macaques develop cross-reactive neutralizing activity. One showed that the X4-tropic SHIVHXB2 or SHIV89.6 and its derivatives generated NAbs against the exquisitely sensitive T-cell–adapted HIV-1MN and HIV-1SF162 strains (20). The cross-reactive neutralizing activity produced by SHIVHXB2–infected monkeys became measurable 76–124 wk PI but not after 21–41 wk of infection. The second study, monitoring anti–HIV-1 NAbs developing in animals infected with the R5-tropic SHIVSF162-P4, reported that autologous neutralization activity appeared within the first month of infection in 11 of 12 macaques and that cross-reactive NAbs became detectable in only 3 of 12 monkeys between 6 and 10 mo PI, with the highest titers directed against the tier 1 HIV-1MN and HIV-1NL4-3 strains (19).

The temporal appearance of cross-reacting neutralizing activity in SHIVAD8–infected macaque CL5E was quite intriguing. At face value, at least two bursts of NAb production occurred in this animal, each apparently targeting HIV-1 strains with different neutralization sensitivities. The first was directed against the sensitive tier 1B HIV-1SS1196.1 (Fig. 4A) and occurred between weeks 5 and 13 PI. Two SHIVAD8–infected macaques also generated cross-reactive NAbs against the neutralization-sensitive SHIVDH12 in the same time frame (between weeks 5 and 10 PI) (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the second wave of NAb production in animal CL5E was delayed until week 41 PI, reaching a peak at week 51, and was directed against more neutralization-resistant HIV-1 isolates. The nearly identical emergence times of the second burst of cross-reactive NAbs suggest that the same conserved epitope may be targeted in each of these viruses. It should be pointed out that the IC50 neutralization titers generated against both the sensitive or the more resistant HIV-1 strains generally correlated with levels of set-point viremia in the SHIVAD8–infected monkeys (Fig. 1 and refs. 13 and 14). For example, macaques DC6W, BIH, CK5T, and DC4N, with some of the highest neutralization titers against the tier 1B SS1196.1 HIV-1 isolate (Figs. 3 and 5), all had set-point plasma viral loads between 103 and 104 viral RNA copies/mL, whereas animal JLD, with a lower level (∼200 RNA copies/mL) of plasma viremia (Fig. 5), had a very low neutralization titer against the SS1196.1 strain. All three macaques (CL5E, DCF1, and DA55) producing NAbs against the more resistant tier 2 HIV-1 isolates had set-point plasma viremia levels between 103 and 104 RNA copies/mL.

The delayed appearance of phase 2 neutralization activity in macaque CL5E is also reminiscent of the emergence of the previously described potent cross-clade NAbs generated by SHIVAD8–infected monkey CE8J, which first became detectable between weeks 32 and 36 PI (12). It is worth noting that a similar two-phase pattern of cross-reacting NAb development has been reported in a longitudinal study of HIV-1–infected individuals (25). The emergence of the second phase required ∼2.5 y during these HIV-1 infections whereas SHIVAD8–infected animals developed activity against more difficult-to-neutralize HIV-1 strains within 1 y of virus inoculation.

Although a time course of NAb development was not determined for each of the 11 SHIVAD8–infected animals listed in Fig. 3, it is quite likely that, in addition to monkey CL5E, macaques DCF1 and DA55, both of which generated neutralization IC50 titers >1:100 against the relatively resistant tier 2 HIV-1JR-FL isolate, also produced both early and late-phase NAbs. Thus, of the 11 SHIVAD8–infected animals intensively evaluated for the development of cross-reacting NAbs (Fig. 3), 3 monkeys likely exhibited a “two-phase” phenotype of NAb development, and 8 monkeys were able to neutralize only sensitive HIV-1 strains. It is not currently known whether or not a common epitope is targeted by the early emerging cross-reactive NAbs in the latter group of SHIVAD8–infected animals.

At present, we do not know which epitopes associated with the SHIVAD8 envelope glycoprotein are driving the production of cross-reactive neutralizing activity or which epitopes in heterologous HIV-1 strains are targeted for neutralization. Because a majority of SHIVAD8–infected monkeys are able to generate cross-reactive neutralizing activity against multiple HIV-1 isolates, studies of B-cell maturation and the generation of broadly reacting NAbs, triggered by a single HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (namely HIV-1AD8) are now possible using the macaque model. One could envisage experiments monitoring B-cell maturation patterns and NAb development in the three SHIVAD8–infected monkeys (CL5E, DCF1, and DA55 in Fig. 3) able to neutralize the tier 2 HIV-1JR-FL isolate at IC50 titers >1:100. The results obtained from such a study could guide the development of immunogens designed to elicit late-phase cross-reactive anti–HIV-1 NAbs.

The failure of many SHIVAD8–infected animals to generate potent and sustained autologous NAbs remains an enigma. We recently reported that only 3 of 19 monkeys inoculated with SHIVAD8 swarm stocks produced autologous neutralizing activity (13), and in the present study only 5 of 8 macaques inoculated with the SHIVAD8-EO molecular clone developed autologous NAbs (Fig. 2A). Perhaps envelope glycoproteins associated with relatively neutralization-resistant HIV-1 strains like the tier 3 HIV-1AD8, rather than envelopes from tissue-culture-adapted virus isolates, may present unique epitopes to the immune system, which elicit an ensemble of cross-reactive NAbs that emerge at different times and possess varying potencies.

Materials and Methods

Construction and Characterization of a Pathogenic SHIVAD8 Molecular Clone.

The strategy used to obtain a potentially pathogenic SHIVAD8 molecular clone was (i) to amplify env gene-containing segments from a previously described (14) cohort of nine animals, infected with serially passaged SHIVAD8 derivatives (Table S1); (ii) to construct full-length SHIV molecular clones carrying some of these amplified env genes; and (iii) to assess the infectivity of reconstructed viruses in rhesus PBMC and in inoculated macaques. The detailed construction of SHIVAD8 molecular clones and the characterization of resulting virus stocks are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Cell Culture.

HEK293T (293T) and TZM-bl cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s MEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FBS. Rhesus monkey PBMCs were prepared and cultured as described previously (26).

Animal Experiments.

Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (27) and were housed in a biosafety level 2 NIAID facility. Phlebotomies, euthanasia, and tissue sample collections were performed as previously described (28). BAL fluid lymphocytes were prepared as previously described (29). All animals were negative for the MHC class I Mamu-A*01 allele.

Quantitation of Plasma Viral RNA Levels.

Viral RNA levels in plasma were determined by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system; Applied Biosystems) as previously reported (28).

Lymphocyte Immunophenotyping and Data Analysis.

EDTA-treated blood samples and BAL fluid lymphocytes were stained for flow cytometric analysis as described previously (30–32).

Neutralization Assays.

The neutralization activity present in plasma samples collected from rhesus macaques infected with molecularly cloned or swarm SHIVAD8 stocks were measured in single-cycle infections of TZM-bl cells by Env pseudoviruses as previously described (14, 33–36). In preliminary assays, 1:20 dilutions of plasma samples were incubated with pseudotyped viruses, expressing the SHIVAD8 CK15-3 amplicon or the env gene derived from SHIVDH12-Cl7 (15) and prepared by cotransfecting 293T cells with pNLenv1 and pCMV vectors expressing the respective envelope proteins, as previously described (14). Any plasma sample causing a 50% reduction of luciferase activity compared with that obtained with an uninfected plasma sample was considered positive for NAbs. All experiments were performed in quadruplicate and repeated twice.

The 50% neutralization inhibitory dose (IC50) titer was calculated as the plasma dilution causing a 50% reduction in relative luminescence units (RLU) compared with levels in virus control wells after subtraction of cell control RLU as previously described (18, 33). The neutralization phenotype (tier levels) of the SHIVAD8 molecular clone was determined by TZM-bl cell assay (18, 33, 36) using plasma samples from a cohort study, which exhibit a wide range of neutralizing activities against subtype B HIV-1 isolates (37).

Neutralization Phenotypes of HIV-1 and SHIV Preparations.

Using standardized plasma pools from HIV-1–infected individuals (18), we determined that the molecularly cloned SHIVAD8-EO exhibited a tier 2 neutralization phenotype (Table S1), the level usually associated with circulating HIV-1 strains. The parental HIV-1AD8 exhibited a tier 3 phenotype in this assay. SHIVDH12CL7 displayed a tier 2 neutralization phenotype with this pool of plasmas.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Keiko Tomioka, Robin Kruthers, and Ranjini Iyengar for determining plasma viral RNA loads and Boris Skopets and Rahel Petros for diligently assisting in the maintenance of animals and assisting with procedures. We are indebted to the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program for providing AMD3100 and to Julie Strizki and Shering Plough for providing AD101. Plasma samples for determining the neutralization phenotype of virus stocks were provided by Áine McKnight through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery/Comprehensive Antibody Vaccine Immune Monitoring Consortium (Grant 38619). This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1217443109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Binley JM, et al. Profiling the specificity of neutralizing antibodies in a large panel of plasmas from patients chronically infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes B and C. J Virol. 2008;82(23):11651–11668. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01762-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doria-Rose NA, et al. Breadth of human immunodeficiency virus-specific neutralizing activity in sera: Clustering analysis and association with clinical variables. J Virol. 2010;84(3):1631–1636. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01482-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doria-Rose NA, et al. Frequency and phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus envelope-specific B cells from patients with broadly cross-neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2009;83(1):188–199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01583-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray ES, et al. Antibody specificities associated with neutralization breadth in plasma from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C-infected blood donors. J Virol. 2009;83(17):8925–8937. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00758-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sather DN, et al. Factors associated with the development of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2009;83(2):757–769. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02036-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simek MD, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite neutralizers: Individuals with broad and potent neutralizing activity identified by using a high-throughput neutralization assay together with an analytical selection algorithm. J Virol. 2009;83(14):7337–7348. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00110-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheid JF, et al. Broad diversity of neutralizing antibodies isolated from memory B cells in HIV-infected individuals. Nature. 2009;458(7238):636–640. doi: 10.1038/nature07930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Euler Z, et al. Longitudinal analysis of early HIV-1-specific neutralizing activity in an elite neutralizer and in five patients who developed cross-reactive neutralizing activity. J Virol. 2012;86(4):2045–2055. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06091-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray ES, et al. and the CAPRISA002 Study Team The neutralization breadth of HIV-1 develops incrementally over four years and is associated with CD4+ T cell decline and high viral load during acute infection. J Virol. 2011;85(10):4828–4840. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00198-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahalanabis M, et al. Continuous viral escape and selection by autologous neutralizing antibodies in drug-naive human immunodeficiency virus controllers. J Virol. 2009;83(2):662–672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01328-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rademeyer C, et al. HIVNET 028 study team Genetic characteristics of HIV-1 subtype C envelopes inducing cross-neutralizing antibodies. Virology. 2007;368(1):172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker LM, et al. Rapid development of glycan-specific, broad, and potent anti-HIV-1 gp120 neutralizing antibodies in an R5 SIV/HIV chimeric virus infected macaque. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(50):20125–20129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117531108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gautam R, et al. Pathogenicity and mucosal transmissibility of the R5-tropic simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIV(AD8) in rhesus macaques: Implications for use in vaccine studies. J Virol. 2012;86(16):8516–8526. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00644-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishimura Y, et al. Generation of the pathogenic R5-tropic simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIVAD8 by serial passaging in rhesus macaques. J Virol. 2010;84(9):4769–4781. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02279-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadjadpour R, et al. Induction of disease by a molecularly cloned highly pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus/human immunodeficiency virus chimera is multigenic. J Virol. 2004;78(10):5513–5519. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5513-5519.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shibata R, et al. Infection and pathogenicity of chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency viruses in macaques: Determinants of high virus loads and CD4 cell killing. J Infect Dis. 1997;176(2):362–373. doi: 10.1086/514053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shibata R, et al. Isolation and characterization of a syncytium-inducing, macrophage/T-cell line-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate that readily infects chimpanzee cells in vitro and in vivo. J Virol. 1995;69(7):4453–4462. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4453-4462.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seaman MS, et al. Tiered categorization of a diverse panel of HIV-1 Env pseudoviruses for assessment of neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2010;84(3):1439–1452. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02108-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraft Z, et al. Macaques infected with a CCR5-tropic simian/human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) develop broadly reactive anti-HIV neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2007;81(12):6402–6411. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00424-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montefiori DC, et al. Neutralizing antibodies in sera from macaques infected with chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency virus containing the envelope glycoproteins of either a laboratory-adapted variant or a primary isolate of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72(4):3427–3431. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3427-3431.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li M, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env clones from acute and early subtype B infections for standardized assessments of vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2005;79(16):10108–10125. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10108-10125.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albert J, et al. Rapid development of isolate-specific neutralizing antibodies after primary HIV-1 infection and consequent emergence of virus variants which resist neutralization by autologous sera. AIDS. 1990;4(2):107–112. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199002000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bunnik EM, Pisas L, van Nuenen AC, Schuitemaker H. Autologous neutralizing humoral immunity and evolution of the viral envelope in the course of subtype B human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2008;82(16):7932–7941. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00757-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montefiori DC, et al. Homotypic antibody responses to fresh clinical isolates of human immunodeficiency virus. Virology. 1991;182(2):635–643. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90604-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikell I, et al. Characteristics of the earliest cross-neutralizing antibody response to HIV-1. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(1):e1001251. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imamichi H, et al. Amino acid deletions are introduced into the V2 region of gp120 during independent pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus/HIV chimeric virus (SHIV) infections of rhesus monkeys generating variants that are macrophage tropic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(21):13813–13818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212511599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals 1985. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) DHHs Publ. No. NIH 85-23, Revised Ed.

- 28.Endo Y, et al. Short- and long-term clinical outcomes in rhesus monkeys inoculated with a highly pathogenic chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2000;74(15):6935–6945. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6935-6945.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Igarashi T, et al. Macrophage-tropic simian/human immunodeficiency virus chimeras use CXCR4, not CCR5, for infections of rhesus macaque peripheral blood mononuclear cells and alveolar macrophages. J Virol. 2003;77(24):13042–13052. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.24.13042-13052.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishimura Y, et al. Resting naive CD4+ T cells are massively infected and eliminated by X4-tropic simian-human immunodeficiency viruses in macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(22):8000–8005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503233102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishimura Y, et al. Loss of naïve cells accompanies memory CD4+ T-cell depletion during long-term progression to AIDS in Simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Virol. 2007;81(2):893–902. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01635-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishimura Y, et al. Highly pathogenic SHIVs and SIVs target different CD4+ T cell subsets in rhesus monkeys, explaining their divergent clinical courses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(33):12324–12329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404620101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shu Y, et al. Efficient protein boosting after plasmid DNA or recombinant adenovirus immunization with HIV-1 vaccine constructs. Vaccine. 2007;25(8):1398–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei X, et al. Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(6):1896–1905. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1896-1905.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willey R, Nason MC, Nishimura Y, Follmann DA, Martin MA. Neutralizing antibody titers conferring protection to macaques from a simian/human immunodeficiency virus challenge using the TZM-bl assay. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(1):89–98. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu X, et al. Mechanism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to monoclonal antibody B12 that effectively targets the site of CD4 attachment. J Virol. 2009;83(21):10892–10907. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01142-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dreja H, et al. Neutralization activity in a geographically diverse East London cohort of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients: Clade C infection results in a stronger and broader humoral immune response than clade B infection. J Gen Virol. 2010;91(Pt 11):2794–2803. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.024224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.