Theoretical and modeling assessments consistently point toward an increase in hurricane intensity with global warming (1–3). For the North Atlantic, the annual number of the most intense hurricanes has been predicted to increase by more than 50% for each 1-°C increase in surface temperatures (2, 4). However, there is no consensus on whether current hurricanes have responded to the substantial global warming that has already occurred (2, 3); some studies find a substantial increase in intense systems (5–7) whereas others find none (8, 9). This presents a conundrum: if we cannot find a current signal, how can we interpret, or even accept, the future projections?

A major issue has been the heterogeneity of most of the available hurricane data, which contain inherent trends in observing and analysis methodologies that are difficult to isolate. This masks any real trends and has generated substantial debate on how to interpret information that may appear to have substantial inherent contradictions.

In PNAS, Grinsted et al. (10) provide a valuable contribution to this debate by way of a homogeneous hurricane proxy record. They synthesize storm-surge data into an index that relates to landfalling hurricanes along the US coast. The method has limitations; for example, the index is weighted toward large, slow-moving hurricanes and small, intense hurricanes are probably undersampled, and surge variations caused by angle of approach to the coast are neglected (spatial inhomogeneity is removed by a normalization procedure). There also are potential issues with changing coastal geography, which may introduce an artificial trend. Nevertheless, the power of their approach lies in the consistency of the database and methodology over time. Provided the errors are randomly distributed, a reasonable assumption, there is confidence that low-frequency variations and long-term trends in the index are indicative of real hurricane changes.

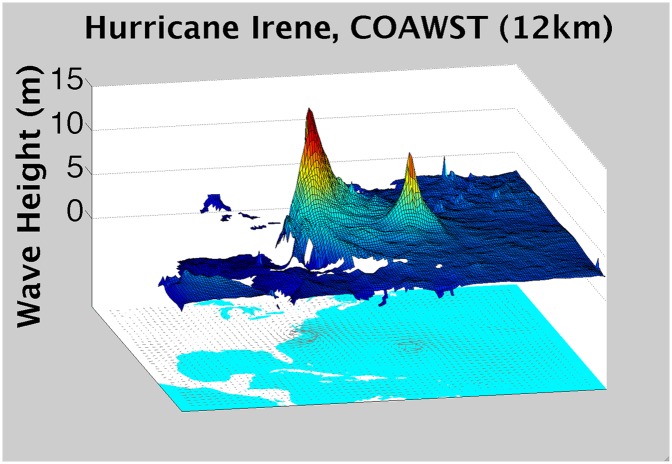

It is often erroneously assumed that hurricane impacts are related entirely to intensity, whereas wind, surge, and ocean wave damage is actually a complex amalgam of wind strength and duration; in other words, hurricane translation and size also contribute (11). The degree of complexity has been amply demonstrated by Hurricanes Katrina and Irene (Fig. 1), whose large sizes were the major factor in the damage that resulted. For offshore structures, provided the system is at hurricane strength, translation speed and size determine almost all the damage that has been observed (11). The surge index provides a physical integration of these factors and this may prove to be its most valuable aspect.

Fig. 1.

Wind (Lower) with overlaid 3D depiction of the near-coastal ocean wave fields associated with Hurricane Irene (left peak), with a second peak over the open ocean driven by Hurricane Katia. COAWST, Coupled-Ocean-Atmosphere-Wave-Sediment-Transport modeling system. (Fields provided by Brian Bonnlander.)

Grinsted et al. (10) show that the index has increased significantly in conjunction with global increases in surface temperature and that the relationship is strongest for the most extreme events. This proxy hurricane relationship with global change bears further investigation, as it has important implications for coastal and offshore planning. There is no doubt that net storm damage is increasing and has done so for several decades, but there is considerable debate on whether hurricane changes have contributed to this or whether it is entirely a result of demographic and economic trends (9, 12, 13). The surge index clearly indicates a climate trend contribution from hurricane extremes. To take a Hurricane Katrina type, Grinsted et al. (10) find that our current climate is experiencing twice as many compared with a few decades ago. Extrapolating the linear trend forward suggests a potential for a further doubling by the end of the century. I consider that a continued frequency increase at this level is unlikely, but any substantial increase in Katrina-like hurricanes is a daunting prospect for current planning.

The observed markedly stronger increase in extreme indices compared with the mean is an expected outcome of the character of the intensity frequency distribution with its exponential decrease as intensity increases (3). For example, the resolution of the current North Atlantic hurricane archive is ∼2.5 ms−1, which is also close to the expected mean intensity change for a 1-°C warming (2). However, by using a Weibull distribution approximation to the current probability distribution function (PDF) of North Atlantic hurricanes and tropical storms, it is straightforward to show that changing the mean and SD by this unobservable amount will more than double the number of Category 4 and 5 hurricanes! Traditionally, there has been a reluctance to look for global change signals in extreme events because of their relative rarity and inherently higher noise level compared with the median population, but, increasingly, there is evidence of a higher signal-to-noise ratio for extremes.

Perhaps we should be looking more to weather extremes as the bellwethers of climate variability and change.

The relationship of the index to global surface temperatures also enters into a related debate on the roles of in situ vs. relative ocean temperatures in determining hurricane activity in the North Atlantic. That there is an in situ relationship has been amply confirmed observationally and theoretically (5, 14, 15). Recently, it has been suggested that relative temperatures in the Atlantic compared with the tropics as a whole are more important (16). I suspect that both have a role, and the importance of relative temperatures certainly has been demonstrated for transient El Niño events (17). However, these relative temperatures are not predicted to change with global warming, and this has been interpreted as meaning that Atlantic hurricanes are not responding (2); the relationship of the index to global temperatures suggests the opposite.

It will be of interest to see where this innovative surge index approach takes us. Perhaps the index can provide a means of removing bias in damage assessments [as Grinsted et al. (10) indicate], provide an independent assessment of damage trends, or be combined with other damage indices (11) to provide a more comprehensive assessment for planning purposes. I suspect that it will be all of these, and that other creative uses will be found for this new and valuable proxy database.

Acknowledgments

The National Center for Atmospheric Research is sponsored by the National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 19601.

References

- 1.Henderson-Sellers A, et al. Tropical cyclones and global climate change: A post-IPCC assessment. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 1998;79:19–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knutson TR, et al. Tropical cyclones and climate change. Nat Geosci. 2010;3:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change . Special Report. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. 2012. Available at http://ipcc-wg2.gov/SREX/images/uploads/SREX-All_FINAL.pdf. Accessed October 29, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bender MA, et al. Modeled impact of anthropogenic warming on the frequency of intense Atlantic hurricanes. Science. 2010;327(5964):454–458. doi: 10.1126/science.1180568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emanuel KA. Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years. Nature. 2005;436(7051):686–688. doi: 10.1038/nature03906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elsner JB. Evidence in support of the climate change—Atlantic hurricane hypothesis. Geophys Res Lett. 2006;33:L16705. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holland GJ, Webster PJ. Heightened tropical cyclone activity in the North Atlantic: Natural variability or climate trend? Phil Trans R Soc A. 2007;365(1860):2695–2716. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2007.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landsea CW, Harper BA, Hoarau K, Knaff JA. Climate change. Can we detect trends in extreme tropical cyclones? Science. 2006;313(5786):452–454. doi: 10.1126/science.1128448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pielke RA, Jr, et al. Normalized hurricane damages in the United States: 1900-2005. Nat Hazards Rev. 2008;9:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grinsted A, Moore JC, Jevrejeva S. Homogeneous record of Atlantic hurricane surge threat since 1923. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:19601–19605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209542109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holland GJ, Done J, Bruyere C, Cooper C, Suzuki-Parker A. Model investigations of the effects of climate variability and change on future Gulf of Mexico tropical cyclone activity. OTC Metocean. 2010;2010:20690. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mills E. Insurance in a climate of change. Science. 2005;309(5737):1040–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.1112121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munich Re North America most affected by increase in weather-related natural catastrophes. 2005. Available at http://www.munichre.com/en/media_relations/press_releases/2012/2012_10_17_press_release.aspx. Accessed October 29, 2012.

- 14.Emanuel KA. Sensitivity of tropical cyclones to surface exchange coefficients and a revised steady-state model incorporating eye dynamics. J Atmos Sci. 1995;52:3969–3976. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruyere C, Holland GJ, Towler E. Investigating the use of a Genesis potential index for tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic Basin. J Climate. 2012 doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00619.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vecchi GA, Soden BJ. Effect of remote sea surface temperature change on tropical cyclone potential intensity. Nature. 2007;450(7172):1066–1070. doi: 10.1038/nature06423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray WM. Atlantic seasonal hurricane frequency. Part I: El Niño and 30 mb quasi-biennial oscillation influences. Mon Weather Rev. 1984;112:1649–1668. [Google Scholar]