Abstract

Hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy) is a well-known independent risk factor for vascular diseases in the general population. This study was to explore the effect of genistein (GST), a natural bioactive compound derived from legumes, on HHcy-induced vascular endothelial impairment in ovariectomized rats in vivo. Thirty-two adult female Wistar rats were assigned randomly into four groups (n = 8): (a) Con: control; (b) Met: 2.5% methionine diet; (c) OVX + Met: ovariectomy + 2.5% methionine diet; (d) OVX + Met + GST: ovariectomy + 2.5% methionine diet + supplementation with genistein. After 12 wk of different treatment, the rats' blood, toracic aortas and liver samples were collected for analysis. Results showed that high-methionine diet induced both elevation of plasma Hcy and endothelial dysfunction, and ovariectomy deteriorated these injuries. Significant improvement of both functional and morphological changes of vascular endothelium was observed in OVX + Met + GST group; meanwhile the plasma Hcy levels decreased remarkably. There were significant elevations of plasma ET-1 and liver MDA levels in ovariectomized HHcy rats, and supplementation with genistein could attenuate these changes. These results implied that genistein could lower the elevated Hcy levels, and prevent the development of endothelial impairment in ovariectomized HHcy rats. This finding may shed a novel light on the anti-atherogenic activities of genistein in HHcy patients.

1. Introduction

Hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy) is a well-known independent risk factor for atherosclerotic diseases in the general population similar to hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and smoking [1–3]. Homocysteine (Hcy) could elicit a cascade of vascular wall injuries including chemical modification of lipoproteins, alterations of vascular structure, endothelial dysfunction, and repair impendence as well as proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells [4–9]. Endothelial impairment can be detected in the early stage of atherosclerosis and serves as one of the leading mechanisms for HHcy-induced vascular dysfunction [7–9]. High levels of Hcy may promote oxidative stress in endothelial cells as a result of production of reactive oxygen species [10, 11], which have been strongly implicated in the development of atherosclerosis.

The Food and Drugs Administration has approved a health claim for soy based on clinical trials and epidemiological data indicating that high soy consumption is associated with a lower risk of coronary artery disease [12–14]. Soy products contain a group of compounds called isoflavone, with genistein (GST) and daidzein being the most abundant. Genistein, as a nonspecific tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has attracted much attention for its potentially beneficial effects on some human cardiovascular events, especially atherosclerosis [15, 16]. The fact that several of the molecular targets of genistein could be linked to atherosclerotic impairment supports the antiatherogenic activities of genistein in endothelial cells [17–19]. However, the underlying mechanisms involved in vascular protective function of genistein remain unclear. Recent studies have shown that genistein may protect vascular endothelial cells against Hcy-induced impairment in vitro [17–21]. However, it is unknown whether the effects of genistein observed in vitro are relevant to an in vivo situation. In this study, we investigated the possible protective effect of genistein on thoracic aortas in ovariectomized HHcy rats induced by high-methionine diet and primarily explored the possible mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Genistein, Hcy, phenylephrine (PE), acetylcholine (ACh), and sodium nitroprusside (SNP) were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA). Factor VIII (also von willebrand factor, vWF) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The rat Hcy enzyme immunometric assay kit was product of Rapidbio Lab (Calabasas, CA, USA). The rat iodine (125I)-17β-estradiol radioimmunoassay kit and iodine (125I)-ET-1 radioimmunoassay kit were purchased from Puerweiye Co. (Beijing, China). The malondialdehyde (MDA) chemiluminescence assay kit was a product of Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). Special rat chow containing 2.5% methionine was purchased from Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College.

2.2. Animals and Treatment Protocols

This investigation conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication no. 85–23, revised 1996) and was performed with approval of the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Thirty-two adult female Wistar rats (8 wk old, weighting 200 ± 20 g) were assigned into four groups randomly (8 rats in each group): (a) Con: normal diet; (b) Met: 2.5% methionine diet; (c) OVX + Met: ovariectomy + 2.5% methionine diet; (d) OVX + Met + GST: ovariectomy + 2.5% methionine diet + GST. GST was dissolved in olive oil (total concentration 1%), 2.5 mg/kg ig daily for 12 wk. For Met and OVX + Met groups rats, same dosage of olive oil ig daily. All rats were allowed free access to water.

After 12 wk special treatment, rats were anesthetized by 20% urethane (1 g/kg, ip). The blood samples were collected from carotid arteries for detecting the plasma 17β-E2, Hcy, and ET-1 levels. Thoracic aorta rings were isolated for the vascular function analysis. The morphological changes of thoracic aortas were also observed by hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, immunohistochemiscal staining of vWF, and scanning electron microscopy. Livers were quickly removed for the MDA detection.

2.3. Measurement of Plasma 17β-E2 and Hcy Levels

The plasma 17β-E2 levels were measured using commercial radioimmunoassay kits (Rat 125I-17β-estradiol RIA kit) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. The plasma Hcy levels were determined by enzyme linked immunometric assay according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

2.4. Vessel Preparation and Functional Study of Isolated Thoracic Aortas Rings

The thoracic aortas were harvested and immediately placed in cold Krebs-Henseleit solution (NaCl 118 mmol/L, KCl 4.75 mmol/L, CaCl2 2.54 mmol/L, NaHCO3 25 mmol/L, KH2PO4 1.19 mmol/L, MgSO4 1.19 mmol/L, glucose 11 mmol/L). Excess tissue and adventitia were carefully removed and three 3 mm rings were cut contiguously from the descending aortas. The endothelium in one of the rings was mechanically destroyed by gently rolling the lumen of the vessel on a toothpick (endothelium-denuded). The rings were suspended in a 10 mL organ bath containing Krebs-Henseleit solution gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, which was maintained at 37°C and connected to force transducer. Changes in isometric tension were analyzed using BL-420E + software. The vascular functions were assessed by their responses to PE, ACh, or SNP. The rings were initially stretched a tension of 0.2 g, allowed to equilibrate for 30 min, and mechanically increased 0.2 g per 5 min until to a basal tension of 2 g. After equilibration, rings were precontracted with PE (10−8 ~ 10−5 mol/L). The ring was discarded if contractile tension was less than 1 g.

The relaxation responses were generated after precontraction of the rings with 10−5 mol/L PE. For studies using endothelium-denuded vessels, the rings were discarded if there was still any degree of relaxation to ACh. The responses to ACh (10−8 ~ 10−5 mol/L) in endothelium-intact rings and responses to SNP (10−9 ~ 10−6 mol/L) in endothelium-denuded rings were detected, respectively. The average of the two results obtained from the two endothelium-intact rings of the same rat was used as one data for statistical analysis.

2.5. Thoracic Aorta Morphological Study

After rats were anesthetized with 20% urethane, the connective tissue of adventitia was removed. The aortas were cut just above the atria. Thoracic aortas were harvested, one segment of 0.5 cm width rings were cut and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated in ethanol, embedded in paraffin, and cross-sectioned (4 μm). Parallel sections were subjected to standard HE staining (Figure 3) or immunohistochemiscal staining of vWF (Figure 4). For scanning electron microscopy (S.E.M.) observation (Figure 5), thoracic aortas were rinsed with ice-cold 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) and fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde for 2 h, then fixed with buffered 2% OsO4 for 2 h and dehydrated in ethanol. Samples were examined and images were acquired using a JEOL JSM-6360LV scanning electron microscopy.

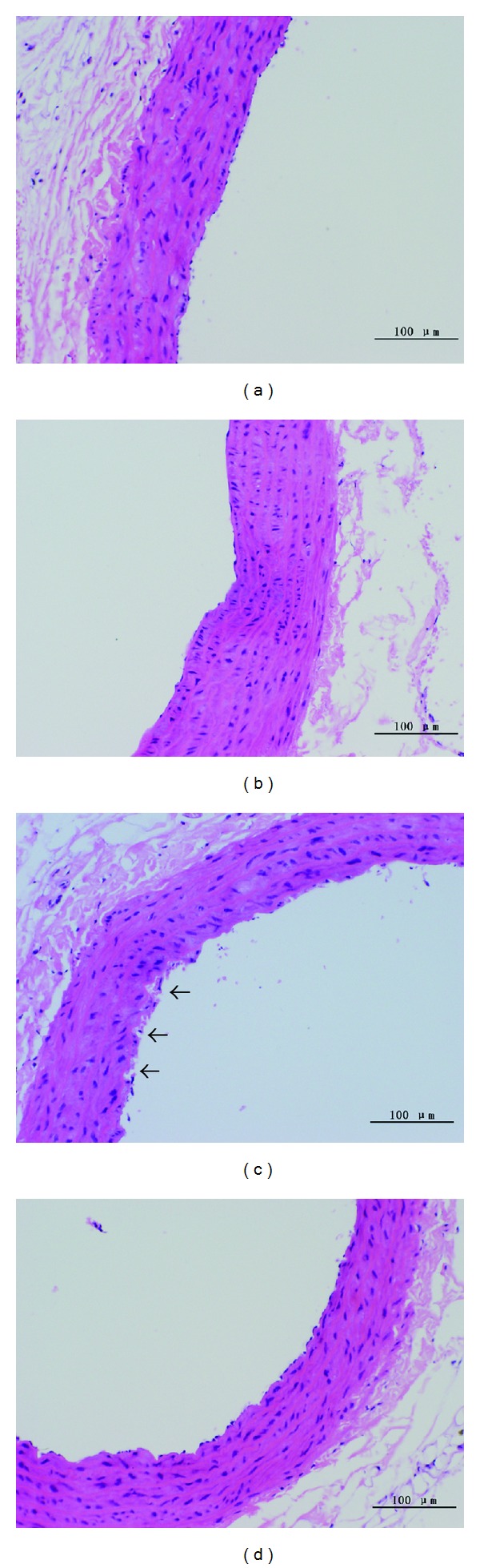

Figure 3.

Effect of genistein on thoracic aorta morphological changes examined by HE staining (×100). (a) Con; (b) Met; (c) OVX + Met; (d) OVX + Met + GST. The tunica intima in OVX + Met group was seriously impaired with plenty of endothelial cell degenerated and desquamated from the wall (showed by ↑). Genistein could significantly improve the morphological changes of endothelium in ovariectomized HHcy rats. The tunica intima in OVX + Met + GST group was almost intact. Smooth muscle cells did not show any difference among different treatments.

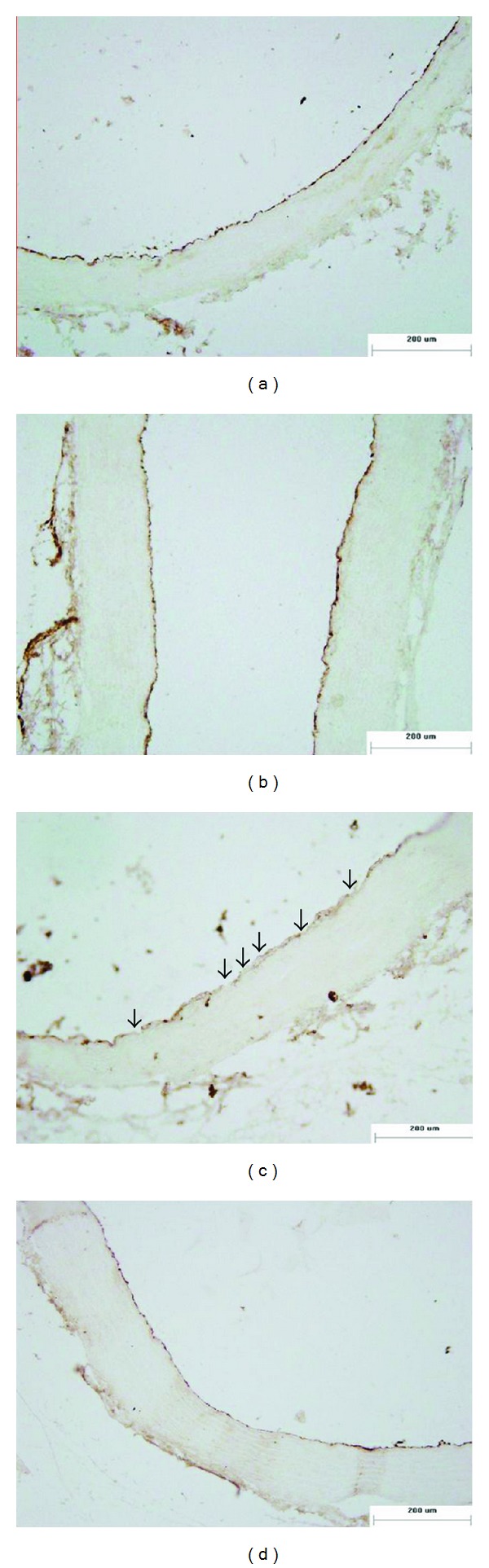

Figure 4.

Effect of genistein on thoracic aortas morphological changes measured by immunohistochemical staining of vWF (×100). (a) Con; (b) Met; (c) OVX + Met; (d) OVX + Met + GST. The continuity of vWF positive staining (indicating endothelium) was interrupted in OVX + Met group, with negative staining in some parts of the inner wall (showed by ↑), while genistein could markedly improve the continuity of vWF positive staining of OVX + Met group.

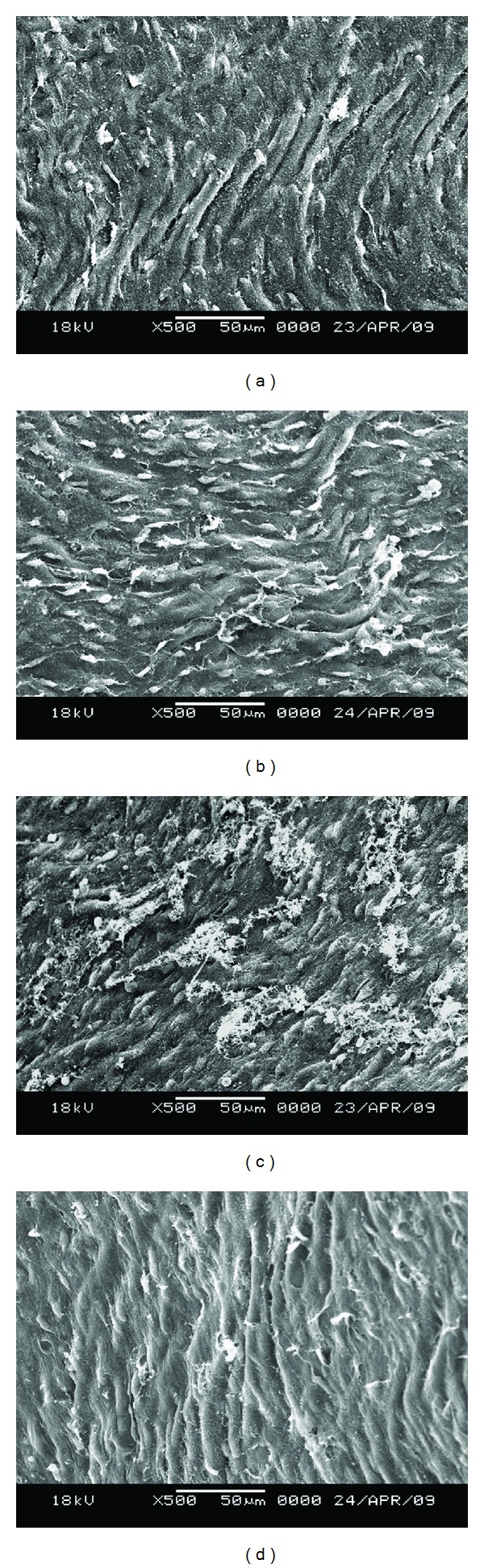

Figure 5.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) observation of inner walls of thoracic aortas (×500). (a) Con; (b) Met; (c) OVX + Met; (d) OVX + Met + GST. The tunica intima was smooth and intact with flat endothelial cells in both Con and Met group. In OVX + Met, the impairment of endothelial cells was very serious with some endothelial cells atrophy, deformed, desquamation, and some fibrin adherent to the endothelium surface. In OVX + Met + GST, the endothelium damage was slight with tunica intima almost intact.

2.6. Measurement of Plasma ET-1 Levels

The plasma ET-1 levels were measured using commercial radioimmunoassay kits (Rat 125I-ET-1 RIA kit) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

2.7. Measurement of Liver MDA Levels

Rats' livers were removed and lysed with saline (100 mg/mL) on the ice. Liver homogenates were centrifuged at 4°C, 12000 rpm, for 10 min. The total protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method. The MDA levels were measured using commercial chemiluminescence assay kits according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

2.8. Data Analysis

Results were presented as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical analysis was done with SPSS 13.0 statistical software. Comparisons between the groups were done using one-way analysis of variance (One-way ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni for post-hoc multiple comparisons. Repeated measures of ANOVA followed by Bonferroni for post-hoc multiple comparisons were used to assess the statistical differences of vascular responses to PE, ACh, and SNP among groups. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Alterations of Plasma 17β-E2 and Hcy Levels after 12 wk Different Treatment

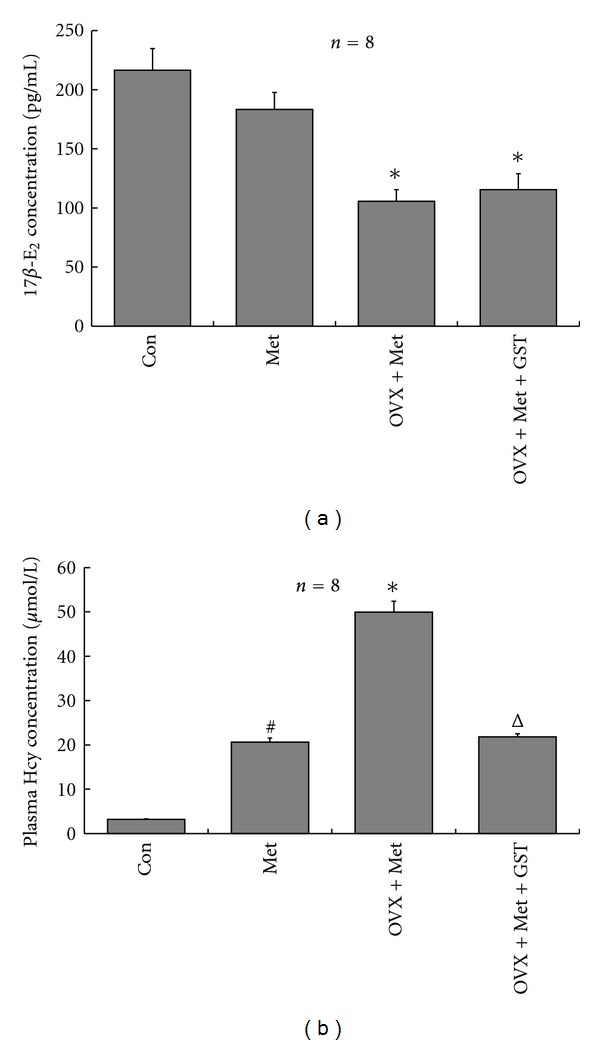

The surgical removal of ovaries (ovariectomy) induced a significant decrease in rat plasma 17β-E2 levels, which confirmed that the ovariectomy has been properly performed in rats (Figure 1(a)). Supplementation with genistein had no significant effect on it. The methionine in diet can metabolize into Hcy in vivo. After 12 wk on 2.5% Met diet, plasma Hcy levels of rats significantly increased (Figure 1(b)). Ovariectomy could further increase the level of Hcy, indicating that the ovariectomized HHcy rat model has been successfully made. Genistein supplementation for 12 wk could significantly lower the elevated Hcy levels in ovariectomized HHcy rats (Figure 1(b)).

Figure 1.

Alterations of plasma 17β-E2 and Hcy levels after 12 wk different treatment. (a) Plasma 17β-E2 levels. Ovariectomy induced a significant decrease of plasma 17β-E2; supplementation with genistein for 12 wk had no significant effect on it. (b) Plasma Hcy levels. 2.5% Met diet for 12 wk induced a significant increase in plasma Hcy levels, and ovariectomy could further enhance the increase of Hcy. Genistein supplementation could significantly lower the elevated Hcy levels. The results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 8), all P values were obtained by one-way ANOVA analysis. #P < 0.05 versus Con; *P < 0.05 OVX + Met versus Met; ΔP < 0.05 versus OVX + Met.

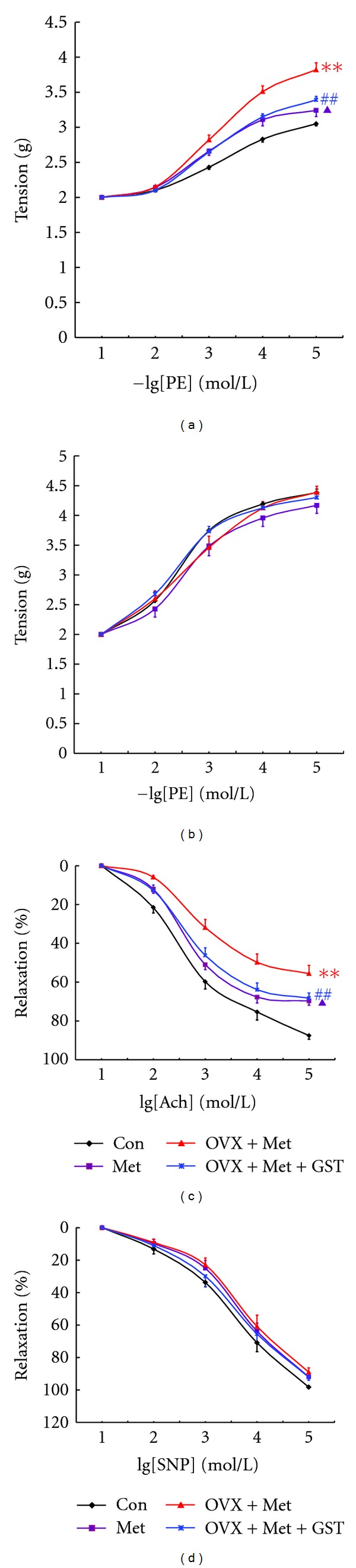

3.2. Effect of Genistein on PE-Induced Contraction of Thoracic Aorta Rings

The data for contraction was expressed as changes in tension in grams. Thoracic aortas were isolated from the rats with different treatments. As expected, PE induced contraction of aortas from all four groups of rats in a dose-dependent manner. However, aortas from rats of Met group showed greater contraction than those from Con rats (Figure 2(a)). Ovariectomy could further increase the contractile response of aortas of Met group. When genistein was added into the diet, the enhanced contraction in ovariectomized HHcy rats was significantly attenuated (Figure 2(a)).

Figure 2.

Effect of genistein on vascular function in ovariectomized HHcy rats. (a) Response to PE of endothelium-intact thoracic aorta rings. 2.5% Met diet for 12 wk induced an enhanced contraction in response to PE, and ovariectomy aggravated this contraction. Supplementation with genistein for 12 wk could significantly attenuate the contraction in ovariectomized HHcy rats. ##P < 0.01 versus Con; **P < 0.01 versus Met, ▲P < 0.05 versus OVX + Met; (b) Response to PE of endothelium-denuded thoracic aortas rings. There was no significant difference in PE-elicited contraction among groups (P > 0.05). (c) Response to ACh of endothelium-intact thoracic aorta rings. HHcy induced a significant decrease in relaxation to ACh, and ovariectomy further decrease this effect. Supplementation with genistein for 12 wk could significantly improve the relaxation to ACh in ovariectomized HHcy rats. ##P < 0.05 versus Con; **P < 0.05 versus Met, ▲P < 0.05 versus OVX + Met; (d) Response to SNP of endothelium-denuded thoracic aortas rings. There was no significant difference in response to SNP among groups (P > 0.05). All the results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA (n = 6 ~ 8).

To investigate whether the above effects were endothelium-dependent, we examined the PE response of endothelium-denuded thoracic aortas rings. As shown in Figure 2(b), there was no significant difference in PE-induced contraction among different groups.

3.3. Effect of Genistein on ACh or SNP-Induced Relaxation of Thoracic Aorta Rings

The data for relaxation was expressed as percentage change after maximal contraction (elicited by 10−5 mol/L PE). ACh could dose-dependently elicit relaxation of aortas. Aortas from rats of Met group showed significantly less relaxation than those from Con group. Ovariectomy further reduced the relaxation response of aortas in Met group. However, enhanced relaxation (22.22%) was observed when genistein was supplemented into the diet of ovariectomized HHcy rats (Figure 2(c)).

Consistent with the contraction response of aortas to PE, there was no significant difference in SNP-induced relaxation of aortas in endothelium-denuded thoracic aorta rings among different groups (Figure 2(d)), indicating that in this study the effects of HHcy, the combination of ovariectomy and HHcy, and genistein on aorta function were endothelium-dependent.

3.4. Effect of Genistein on Thoracic Aortas Morphological Changes

Optical microscopic observation (HE staining) showed that the tunica intima was intact in both Con and Met groups, while the tunica intima in OVX + Met group was seriously impaired as indicated by degeneration of plenty of endothelial cells and their desquamation from the vascular wall. Supplementation with genistein for 12 wk could significantly improve morphological changes of the vascular endothelium induced by the combination of ovariectomy and methionine diet. The morphological characteristics of smooth muscle cells were similar in all groups (Figure 3).

Since vWF was regarded as specific marker of endothelial cells, we further performed immunohistochemical positive staining of vWF to confirm the above changes of the tunica intima. As shown in Figure 4, the continuity of vWF positive staining was interrupted in OVX + Met group with no positive staining in some parts of the inner wall, which indicated the endothelium was seriously destroyed, whereas the continuity of vWF positive staining was significantly improved when genistein was added into the diet, demonstrating that genistein supplementation could attenuate HHcy-induced endothelial impairment (Figure 4).

In addition, scanning electron microscopy was used to detect the ultrastructural changes of endothelium (Figure 5). The results showed that the tunica intima was smooth and intact with flat endothelial cells in both Con and Met groups, whereas in OVX + Met group, the tunica intima showed serious impairment, including atrophy, deformation and desquamation of endothelial cells, and adhesion of fibrin to the endothelium surface. After genistein was applied, the impairment of endothelium was markedly improved.

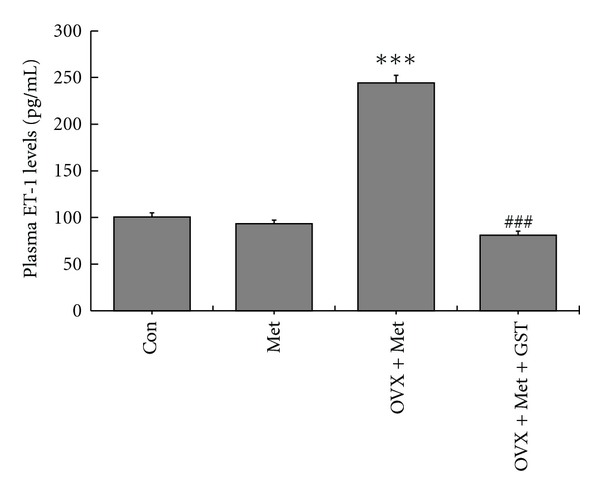

3.5. Effect of Genistein on Plasma ET-1 Levels

Compared with Con group, there was no obvious elevation of the plasma ET-1 in Met group, while ovariectomy induced a significant elevation of plasma ET-1 in OVS + Met group. Genistein supplementation could reverse the increased plasma ET-1 levels of OVX + Met group (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Alterations of plasma ET-1 levels after 12 wk different treatment. There was a significant increase of plasma ET-1 levels in ovariectomized HHcy rats. Supplementation with genistein could significantly lower the elevated Hcy levels. The results shown are mean ± SEM, n = 8. P values were obtained by one-way ANOVA analysis. ***P < 0.001 versus Met; ###P < 0.001 versus OVX + Met.

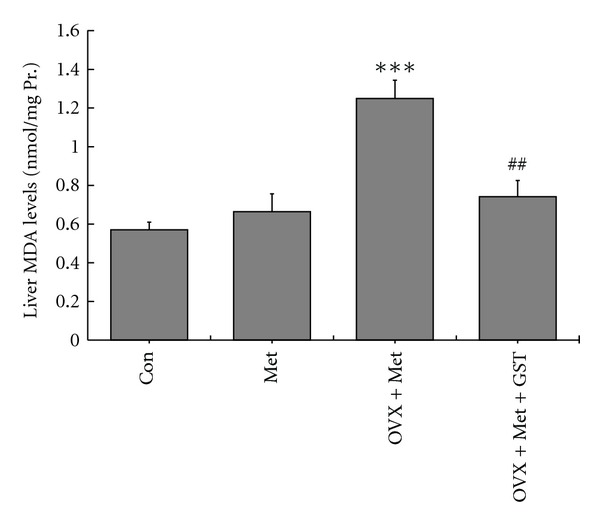

3.6. Effect of Genistein on Liver MDA Levels

Since oxidative stress is a critical contributing factor to HHcy-induced endothelial dysfunction [22–24], and genistein has been shown to have antioxidant activity [13, 15], we further explored whether genistein could reduce oxidative stress in ovariectomized HHcy rats using liver MDA level as index [22]. As shown in Figure 7, there was no significant difference in liver MDA levels between Met and Con group, while ovariectomy caused a significant increase of liver MDA levels in OVX + Met group. In rats of OVX + Met + GST group, the liver MDA levels were significant lower than that in OVX + Met, indicating that supplementation with genistein could reduce oxidative stress in ovariectomized HHcy rats.

Figure 7.

Alterations of liver MDA levels after 12 wk different treatment. There was a significant increase of liver MDA levels in ovariectomized HHcy rats. Genistein supplementation could significantly lower the elevated MDA levels. The results are shown as mean ± SEM, n = 8. P values were obtained by one-way ANOVA analysis. ***P < 0.001 versus Met; ##P < 0.01 versus OVX + Met.

4. Discussion

In the last several decades, HHcy has been recognized as a risk factor for development of atherosclerosis and other vascular diseases. One of the mechanisms by which elevated Hcy impairs the vessel wall is Hcy-induced endothelial dysfunction [7–9]. It has been known that the vascular relaxation in response to ACh is endothelium-dependent, which is dependent on the nitric oxide (NO) released from endothelial cells [25]. On the other hand, SNP, serving as NO donor, could relax smooth muscle cells directly in an endothelium-independent way [26]. Our study did not show any significant difference in the function of endothelium-denuded thoracic aorta rings in response to either PE or SNP among different groups, suggesting HHcy-induced vascular injury is mainly in endothelial cells. The morphological alterations of thoracic aortas also supported this point. These results were consistent with previous reports [26–28]. It was ever reported that HHcy might induce elastin breakdown and collagen replacement, leading to decreased vascular compliance [27]. However, in this study, the rats in Met group showed a significant greater contraction in response to PE and less relaxation to ACh in endothelium-intact thoracic aortas rings than normal rats, which could be further aggravated by ovariectomy. These results implicated that the development of decreased vascular compliance might require longer exposure to HHcy.

Genistein, a major isoflavone abundant in soy, has been shown its potent vascular protective function [15–19]. In this study, we investigated the protective effects of genistein on endothelial function by using the chronic, mild, diet-induced HHcy rat model. Since genistein has a weak estrogenic effect [15], in order to exclude the potential interference from the estrogenic effect of genistein, we performed ovariectomy in HHcy rats before applying genistein. Our results showed that dietary intervention of genistein significantly attenuate endothelial impairment both in function and morphology in ovariectomized HHcy rats. It was consistent with the previous in vitro findings that genistein might protect endothelial cells from Hcy-induced impairment [19–21].

The mechanisms involved in vascular protective function of genistein are complicate. Besides its nonspecific tyrosine kinase inhibitory role, genistein could exert vascular protective action through many other signaling pathways, such as cAMP/protein kinase A and PI3 K/AKT pathways [29]. Extensive studies show that it could reduce the level of LDL cholesterol, inhibit production of proinflammatory cytokines and cell adhesion proteins, and suppress platelet aggregation [13, 22, 30]. Recent findings have shown that genistein induces production of nitric oxide (NO) and reduces reactive oxygen species (ROS) through upregulating endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and attenuating the expression of ROS-producing enzymes, respectively [31, 32]. It has been known that ROS are fundamentally involved in HHcy-induced endothelial dysfunction [22–24]. ROS, especially superoxide anion, could reduce the bioavailability of NO, leading to impaired vascular reactivity [33, 34]. MDA was the product of cell membrane lipid peroxidation with ROS, and was often used as index of oxidative stress in vivo [35]. In this study, ovariectomized HHcy rats showed a significant elevation in MDA levels of liver, which could be reduced by genistein supplementation. This result indicated that genistein could attenuate the oxidative damage in HHcy rats, consistent with its known antioxidant activity. However, whether the other effects of genistein on endothelium, such as the induction of NO, could also contribute to its vascular protective function in HHcy rat model remains to be further explored. Furthermore, whether its antioxidant activity in endothelial cells links with its tyrosine kinases inhibitory role is unclear, although tyrosine kinase pathway has been shown to induce ROS in certain types of cells [36, 37].

ET-1, a 21-amino acid polypeptide, is mainly derived from endothelial cells. Beyond its vasoconstrictive properties, ET-1 plays a key role in the development of endothelial dysfunction. ET-1 activates NADPH oxidases and thereby increases superoxide production, resulting in oxidative stress via the ET receptor-proline-rich tyrosine kinase-2-(Pyk2-)Rac1 pathway [38]. Rac1 is an important regulator of NADPH oxidase. ET-1 can also decrease NO bioavailability either by decreasing its production (caveolin-1-mediated inhibition of eNOS activity) or by increasing its degradation (via formation of ROS) [39]. It is possible that ET-1 work as a causative factor of endothelial damage in the “OVX + Met” animal group in this study. ET-1 production by endothelial cells can be enhanced by a variety of endogenous and exogenous dangerous factors. Upregulation of preproendothelin-1 gene expression was associated with protein tyrosine kinases-PI3 K signaling [40]. Elevated plasma ET-1 levels have been directly associated with endothelial dysfunction. As an inhibitor of tyrosine kinases, gensistein maybe block HHcy-induced endothelial dysfunction by either suppressing ROS production (Rac1 pathway) or ET-1 production (PI3 K signaling), or both. At present, we have not provided enough evidence to support this hypothesis; additional time and effort are required to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our results showed that HHcy induced endothelial dysfunction in rats, which could be aggravated by ovariectomy. Genistein could improve endothelial function by directly decreasing the elevated plasma Hcy levels, as well as ameliorating the oxidative stress. Though the underlying mechanisms responsible for this effect need to be explored, this finding could shed a novel light on the antiatherogenic activities of genistein in HHcy patients.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (no. 7112012), Open Foundation of the Key Laboratory of Remodeling-Related Cardiovascular Diseases (no. 2012XXGB01), and Scientific Research Common Program of Beijing Municipal Commission of Education (no. KM200910025003). The authors thank Dr. Wei Liu from National Institutes of Health (MD, USA) for insightful comments and careful revision.

References

- 1.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362(6423):801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoniades C, Antonopoulos AS, Tousoulis D, Marinou K, Stefanadis C. Homocysteine and coronary atherosclerosis: from folate fortification to the recent clinical trials. European Heart Journal. 2009;30(1):6–15. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch GN, Loscalzo J. Homocysteine and atherothrombosis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338(15):1042–1050. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804093381507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang PY, Lu SC, Lee CM, et al. Homocysteine inhibits arterial endothelial cell growth through transcriptional downregulation of fibroblast growth factor-2 involving G protein and DNA methylation. Circulation Research. 2008;102(8):933–941. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.171082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austin RC, Lentz SR, Werstuck GH. Role of hyperhomocysteinemia in endothelial dysfunction and atherothrombotic disease. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2004;11(supplement 1):S56–S64. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hossain GS, van Thienen JV, Werstuck GH, et al. TDAG51 is induced by homocysteine, promotes detachment-mediated programmed cell death, and contributes to the development of atherosclerosis in hyperhomocysteinemia. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(32):30317–30327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212897200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers JC, McGregor A, Jean-Marie J, Obeid OA, Kooner JS. Demonstration of rapid onset vascular endothelial dysfunction after hyperhomocysteinemia: an effect reversible with vitamin C therapy. Circulation. 1999;99(9):1156–1160. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.9.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanani PM, Sinkey CA, Browning RL, Allaman M, Knapp HR, Haynes WG. Role of oxidant stress in endothelial dysfunction produced by experimental hyperhomocyst(e)inemia in humans. Circulation. 1999;100(11):1161–1168. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.11.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eberhardt RT, Forgione MA, Cap A, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in a murine model of mild hyperhomocyst(e)inemia. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;106(4):483–491. doi: 10.1172/JCI8342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tyagi N, Sedoris KC, Steed M, Ovechkin AV, Moshal KS, Tyagi SC. Mechanisms of homocysteine-induced oxidative stress. American Journal of Physiology. 2005;289(6):H2649–H2656. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00548.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edirimanne VER, Woo CWH, Siow YL, Pierce GN, Xie JY, Karmin O. Homocysteine stimulates NADPH oxidase-mediated superoxide production leading to endothelial dysfunction in rats. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2007;85(12):1236–1247. doi: 10.1139/Y07-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker SE, Adams MR, Franke AA, Register TC. Effects of dietary soy protein on iliac and carotid artery atherosclerosis and gene expression in male monkeys. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196(1):106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wenzel U, Fuchs D, Daniel H. Protective effects of soy-isoflavones in cardiovascular disease: identification of molecular targets. Hamostaseologie. 2008;28(1-2):85–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker SE, Register TC, Appt SE, et al. Plasma lipid-dependent and -independent effects of dietary soy protein and social status on atherogenesis in premenopausal monkeys: implications for postmenopausal atherosclerosis burden. Menopause. 2008;15(5):950–957. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181612cef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Si H, Liu D. Phytochemical genistein in the regulation of vascular function: new insights. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2007;14(24):2581–2589. doi: 10.2174/092986707782023325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rimbach G, Boesch-Saadatmandi C, Frank J, et al. Dietary isoflavones in the prevention of cardiovascular disease—a molecular perspective. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46(4):1308–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuchs D, Dirscherl B, Schroot JH, Daniel H, Wenzel U. Soy extract has different effects compared with the isolated isoflavones on the proteome of homocysteine-stressed endothelial cells. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research. 2006;50(1):58–69. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuchs D, de Pascual-Teresa S, Rimbach G, et al. Proteome analysis for identification of target proteins of genistein in primary human endothelial cells stressed with oxidized LDL or homocysteine. European Journal of Nutrition. 2005;44(2):95–104. doi: 10.1007/s00394-004-0499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuchs D, Dirscherl B, Schroot JH, Daniel H, Wenzel U. Proteome analysis suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction in stressed endothelial cells is reversed by a soy extract and isolated isoflavones. Journal of Proteome Research. 2007;6(6):2132–2142. doi: 10.1021/pr060547y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Si H, Liu D. Isoflavone genistein protects human vascular endothelial cells against tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis through the p38beta mitogen-activated protein kinase. Apoptosis. 2009;14(1):66–76. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0283-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuchs D, Erhard P, Rimbach G, Daniel H, Wenzel U. Genistein blocks homocysteine-induced alterations in the proteome of human endothelial cells. Proteomics. 2005;5(11):2808–2818. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahn K, Borrás C, Knock GA, et al. Dietary soy isoflavone induced increases in antioxidant and eNOS gene expression lead to improved endothelial function and reduced blood pressure in vivo. The FASEB Journal. 2005;19(12):1755–1757. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4008fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolling J, Scherer EB, da Cunha AA, da Cunha MJ, Wyse ATS. Homocysteine induces oxidative-nitrative stress in heart of rats: prevention by folic acid. Cardiovascular Toxicology. 2011;11(1):67–73. doi: 10.1007/s12012-010-9094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss N. Mechanisms of increased vascular oxidant stress in hyperhomocysteinemia and its impact on endothelial function. Current Drug Metabolism. 2005;6(1):27–36. doi: 10.2174/1389200052997357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature. 1980;288(5789):373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Andrade CR, Fukada SY, Olivon VC, et al. α1D-adrenoceptor-induced relaxation on rat carotid artery is impaired during the endothelial dysfunction evoked in the early stages of hyperhomocysteinemia. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2006;543(1–3):83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mujumdar VS, Aru GM, Tyagi SC. Induction of oxidative stress by homocyst(e)ine impairs endothelial function. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2001;82(3):491–500. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansrani M, Stansby G. The use of an in vivo model to study the effects of hyperhomocysteinaemia on vascular function. Journal of Surgical Research. 2008;145(1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng FL, Zhao JH, Zhang HP. The action of PI3K/AKT during genistein promoting the activity of eNOS. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2012;40(4):327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu X, Cheng X, Xie JJ, et al. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition improves endothelial dysfunction induced by hyperhomocysteinemia in rats. Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy. 2009;23(2):121–127. doi: 10.1007/s10557-008-6146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho HY, Park CM, Kim MJ, Chinzorig R, Cho CW, Song YS. Comparative effect of genistein and daidzein on the expression of MCP-1, eNOS, and cell adhesion molecules in TNF-α-stimulated HUVECs. Nutrition Research and Practice. 2011;5(5):381–388. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2011.5.5.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Si H, Yu J, Jiang H, Lum H, Liu D. Phytoestrogen genistein up-regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression via activation of cAMP response element-binding protein in human aortic endothelial cells. Endocrinology. 2012;153(7):3190–3198. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wassmann S, Wassmann K, Nickenig G. Modulation of oxidant and antioxidant enzyme expression and function in vascular cells. Hypertension. 2004;44(4):381–386. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000142232.29764.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vásquez-Vivar J, Whitsett J, Martásek P, Hogg N, Kalyanaraman B. Reaction of tetrahydrobiopterin with superoxide: EPR-kinetic analysis and characterization of the pteridine radical. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2001;31(8):975–985. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00680-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, et al. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1988;332(6163):411–415. doi: 10.1038/332411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sattler M, Verma S, Shrikhande G, et al. The BCR/ABL tyrosine kinase induces production of reactive oxygen species in hematopoietic cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(32):24273–24278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002094200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang J, Wu LJ, Tashino SI, Onodera S, Ikejima T. Protein tyrosine kinase pathway-derived ROS/NO productions contribute to G2/M cell cycle arrest in evodiamine-treated human cervix carcinoma HeLa cells. Free Radical Research. 2010;44(7):792–802. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2010.481302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dammanahalli KJ, Sun Z. Endothelins and NADPH oxidases in the cardiovascular system. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2008;35(1):2–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iglarz M, Clozel M. Mechanisms of ET-1-induced endothelial dysfunction. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2007;50(6):621–628. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31813c6cc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J, Narayan VM, Juedes N, Patel JM. Hypoxic upregulation of preproendothelin-1 gene expression is associated with protein tyrosine kinase-PI3K signaling in cultured lung vascular endothelial cells. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 2009;2(1):87–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]